Abstract

Aims

Invasive cribriform and intraductal carcinoma (IDC) are associated with adverse outcome in prostate cancer patients, with the large cribriform pattern having the worst outcome in radical prostatectomies. Our objective was to determine the impact of the large and small cribriform patterns in prostate cancer biopsies.

Methods and results

Pathological revision was carried out on biopsies of 1887 patients from the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. The large cribriform pattern was defined as having at least twice the size of adjacent benign glands. The median follow‐up time was 13.4 years. Hazard ratios for metastasis‐free survival (MFS) and disease‐specific survival (DSS) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Any cribriform pattern was found in 280 of 1887 men: 1.1% IDC in grade group (GG) 1, 18.2% in GG2, 57.1% in GG3, 55.4% in GG4 and 59.3% in GG5; the large cribriform pattern was present in 0, 0.5, 9.8, 18.1 and 17.3%, respectively. In multivariable analyses, small and large cribriform patterns were both (P < 0.005) associated with worse MFS [small: hazard ratio (HR) = 3.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.93–4.78; large: HR = 3.17, 95% CI = 1.68–5.99] and DSS (small: HR = 4.07, 95% CI = 2.51–6.62; large: HR = 4.13, 95% CI = 2.14–7.98). Patients with the large cribriform pattern did not have worse MFS (P = 0.77) or DSS (P = 0.96) than those with the small cribriform pattern.

Conclusions

Both small and large cribriform patterns are associated with worse MFS and DSS in prostate cancer biopsies. Patients with the large cribriform pattern on biopsy have a similar adverse outcome as those with the small cribriform pattern.

Keywords: biopsy, cribriform, intraductal carcinoma, prostate cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men worldwide. 1 Clinical management of patients with prostate cancer mainly depends upon clinical tumour stage, serum prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) and biopsy Gleason score/grade group. Currently, patients with Gleason score ≤ 3 + 3 = 6 (grade group 1) are monitored by active surveillance, while patients with Gleason score ≥ 4 + 3 = 7 (grade group ≥ 3) typically receive active treatment. The most beneficial treatment for individual patients with Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 (grade group 2) is not yet clear.2 Most patients with grade group 2 cancer will receive active treatment in the form of radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy, although active surveillance is increasingly being considered in selected men with favourable intermediate‐risk disease. 3 To aid clinical decision‐making there is a need for clearer risk stratification for this group of patients.

Gleason score 7 prostate cancer comprehends a mixture of well‐differentiated Gleason pattern 3 glands interspersed with Gleason pattern 4 tumour structures. Gleason pattern 4 cancer comprises different growth patterns, categorised as poorly formed, fused, glomeruloid and cribriform. 4 , 5 , 6 Numerous studies have shown that the presence of an invasive cribriform pattern accounts for worse biochemical recurrence‐free survival (BCRFS), metastasis‐free survival (MFS) and disease‐specific survival (DSS) in comparison to patients without invasive cribriform architecture, both in prostate biopsies as well as radical prostatectomies. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Intraductal carcinoma (IDC) is characterised as a proliferation of malignant epithelial cells confined to distended pre‐existent acini and prostatic ducts, and is mainly accompanied by invasive prostate carcinoma. 13 Like invasive cribriform carcinoma, the presence of IDC is an adverse prognostic factor and both significantly increase the discriminative power of prediction models, including other relevant clinicopathological parameters. 8 The 2019 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus meeting and the Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) therefore recommend commenting upon the presence/absence of invasive cribriform and intraductal carcinoma in all prostate cancer pathology reports. 5 , 6

Because the reporting of cribriform architecture is important for clinical decision‐making, details on the definition of cribriform pattern and its distinction from potential mimickers are coming to attention. 2 In earlier studies, different‐sized thresholds have been used for cribriform pattern definition. For instance, Iczkowski et al. required the presence of more than 12 luminal spaces in a cribriform structure, while Trudel et al. included lesions exceeding the size of an average benign gland and Van Leenders et al. did not set a specific size limitation. 7 , 14 , 15 Furthermore, Hollemans et al. found that grade group 2 patients with large cribriform structures exceeding twice the size of adjacent benign glands at radical prostatectomy had shorter BCRFS than men with small cribriform glands. 16 It is currently unknown whether large cribriform structures at diagnostic biopsies are also associated with worse outcome compared to small cribriform glands. The objective of the current study is to determine whether large cribriform structures have independent adverse predictive value for clinical outcome compared to small cribriform architecture in a large cohort of prostate cancer biopsies with long‐term follow‐up.

Materials and methods

PATIENT SELECTION

All 1951 men diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma in screening rounds 1–3 from the Dutch part of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) were included in this study. 17 , 18 The participants had undergone systematic sextant biopsies and one to two targeted biopsies in case of a visible lesion at transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) prompted by an elevated PSA level between November 1993 and January 2010 at Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, in accordance with the previously published trial protocol. 17 , 18 Exclusion criteria were presence of distant or lymph node metastasis at first diagnosis (n = 28) and unavailability of slides or paraffin blocks for pathological review (n = 36), leaving a total of 1887 patients for further analysis. This study was approved by the institutional Medical Research Ethics Committee (MEC‐2018‐1614).

PATHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

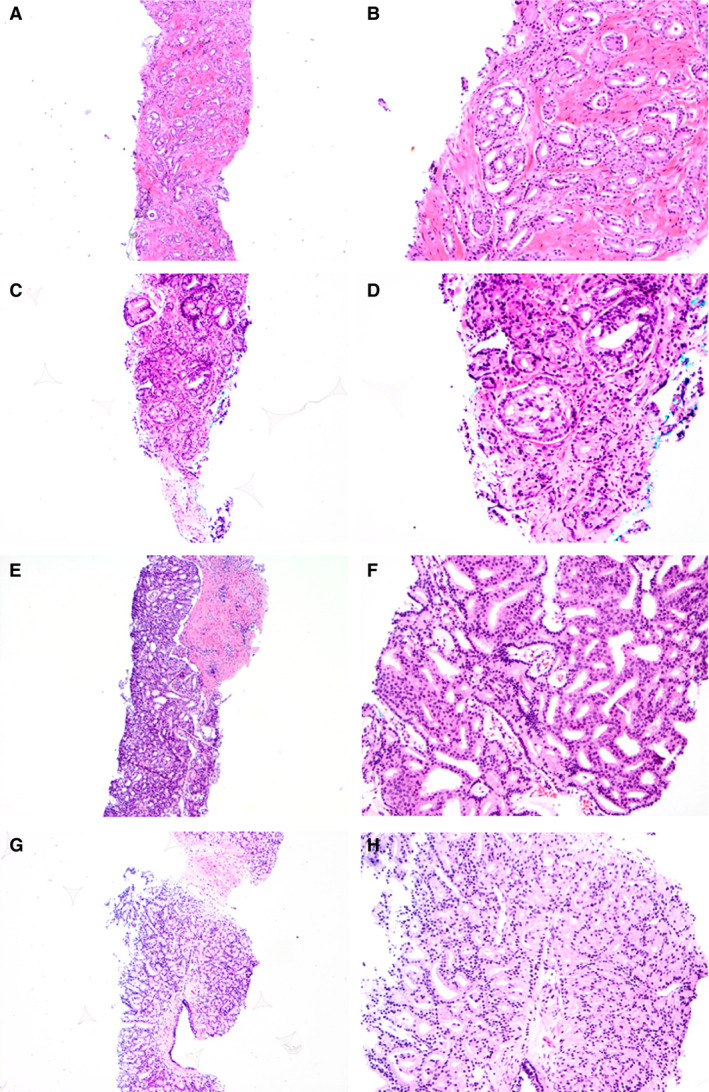

All biopsies were revised by one senior pathologist (G.v.L.) together with a combination of four junior (C.K., I.K., L.R., T.H.) pathologists, who each reviewed a subset of the cases. In case of discordances, the senior pathologist's assessment was recorded. The observers were all blinded to clinical information and patient outcome. For each biopsy we recorded tumour length in millimetres, highest Gleason score/grade group according to the 2014 ISUP recommendations and the presence of invasive cribriform and intraductal carcinoma. 4 Cribriform carcinoma was defined as a contiguous proliferation of malignant epithelial cells with the majority of tumour cells not being in contact with adjacent stroma and with identifiable intercellular lumina. 15 , 19 A large cribriform pattern was defined as having a diameter of at least twice the size of adjacent benign glands, while the diameter of a small cribriform pattern was smaller than twice the size of pre‐existing benign glands (Figure 1). IDC was distinguished from high‐grade prostate intra‐epithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) by morphological features as described by Guo et al., and not incorporated into the grade group assessment. 13 Because their considerable morphological overlap requires basal cell immunohistochemistry for differentiation, invasive cribriform and intraductal carcinoma were analysed as one group (invCR/IDC). If a case had both large and small invCR/IDC, it was classified as large cribriform in further analysis.

Figure 1.

Prostate cancer biopsies with small (A–D) and large (E–H) cribriform patterns. The large cribriform pattern was defined as having a diameter of at least twice the size of adjacent benign glands, while the diameter of the small cribriform pattern was smaller than twice the size of pre‐existing benign glands.

CLINICAL FOLLOW‐UP

After diagnosis and initial treatment, patients were monitored half‐yearly by chart review to assess disease progression and secondary treatment. Cause of death was independently evaluated by a cause of death committee.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous parameters were analysed with either the Mann–Whitney U ‐test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical parameters were analysed with the Pearson's χ2 test. Log2 transformation was used for non‐normally distributed continuous variables to reflect doubling effects. Hazard ratios for MFS and DSS were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Results were considered significant when the two‐sided P‐value was <0.05.

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

The median age of the patients (n = 1887) at time of diagnosis was 67.3 years [interquartile range (IQR) = 63.7–70.9] and median PSA level was 4.6 ng/ml (IQR = 3.4–7.1). Of all patients, 1116 (59.1%) had grade group 1, 444 (23.5%) grade group 2, 163 (8.6%) grade group 3, 83 (4.4%) grade group 4 and 81 (4.3%) grade group 5 cancer. In total, 1479 (78.4%) patients received active treatment, while 407 (21.6%) patients were monitored by watchful waiting/active surveillance. In total, 662 (35.1%) patients underwent radical prostatectomy, 791 (41.9%) patients had radiotherapy and 44 (2.3%) received endocrine treatment. Grade group was positively correlated with age (P = 0.004), PSA level (P < 0.001) and percentage of positive biopsy cores (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Patients with a higher grade group more often received radiotherapy (P < 0.001) and endocrine treatment (P = 0.006) and less often watchful waiting/active surveillance (P < 0.001). The median follow‐up time with censoring of deaths was 13.4 years (IQR = 10.6–17.1) and 12.5 years (IQR = 8.9–16.5) without censoring.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Grade group 1 | Grade group 2 | Grade group 3 | Grade group 4 | Grade group 5 | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1116 | 444 | 163 | 83 | 81 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 66.7 (67.0: 63.2–70.5) | 66.9 (67.1: 63.4–71.0) | 68.1 (68.8: 64.9–71.9) | 67.9 (68.0: 65.2–71.5) | 66.9 (67.1: 63.6–70.9) | 0.004 a |

| PSA level at diagnosis (ng/ml) | 5.2 (4.2: 3.2–5.9) | 7.7 (5.2: 3.6–8.0) | 10.4 (5.9: 4.3–11.1) | 16.1 (9.2: 4.8–16.2) | 15.5 (7.8: 5.3–15.6) | <0.001 a |

| Percentage of positive cores (%) | 29.9 (25.0: 16.7–33.3) | 43.0 (42.9: 28.6–57.1) | 51.6 (50.0: 28.6–57.1) | 51.6 (50.0: 33.3–71.4) | 59.9 (57.1: 42.9–85.7) | <0.001 a |

| All cribriform | 12 (1.1) | 81 (18.2) | 93 (57.1) | 46 (55.4) | 48 (59.3) | <0.001 b |

| Small cribriform/IDC | 12 (1.1) | 79 (17.8) | 77 (47.2) | 31 (37.3) | 34 (42.0) | <0.001 b |

| Large cribriform | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 16 (9.8) | 15 (18.1) | 14 (17.3) | <0.001 b |

| Radical prostatectomy | 385 (34.5) | 172 (38.7) | 60 (36.8) | 26 (31.3) | 19 (23.5) | 0.081 b |

| Radiotherapy | 391 (35.0) | 203 (45.7) | 86 (52.8) | 53 (63.9) | 58 (71.6) | <0.001 b |

| Endocrine treatment | 17 (1.5) | 13 (2.9) | 6 (3.7) | 2 (2.4) | 6 (7.4) | 0.006 b |

| Watchful waiting/active surveillance | 328 (29.4) | 61 (13.7) | 13 (8.0) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (2.5) | <0.001 b |

| Radiotherapy and endocrine treatment | 5 (0.4) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.9) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | |||||

| Prostate cancer‐specific deaths | 22 (2.0) | 27 (6.1) | 30 (18.4) | 20 (24.1) | 24 (29.6) | <0.001 b |

Mean (median, interquartile range) or n (%) total: N = 1887.

PSA, prostate‐specific antigen; IDC, intraductal carcinoma.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

Pearson's χ2 test.

CRIBRIFORM ARCHITECTURE

Any invasive cribriform and/or intraductal carcinoma (invCR/IDC) was observed in 280 (14.8%) men. The percentage of men with invCR/IDC was highest in grade groups 3–5: 12 of 1116 (1.1%) men in grade group 1 had IDC, 81 of 444 (18.2%) had invCR/IDC in grade group 2, 93 of 163 (57.1%) in grade group 3, 46 of 83 (55.4%) in grade group 4 and 48 of 81 (59.3%) in grade group 5. Men with invCR/IDC were of significantly older age (P = 0.006) and had significantly higher PSA levels (P < 0.001) than those without. A total of 260 (92.1%) patients with invCR/IDC received active treatment: 89 of 280 (31.8%) patients underwent radical prostatectomy, 157 of 280 (56.1%) had radiotherapy, seven of 280 (2.5%) received endocrine treatment and seven of 280 (2.5%) received both radiotherapy and endocrine treatment.

A total of 233 of 1887 (12.3%) patients had the small invasive cribriform growth pattern and/or IDC. The highest percentage of men with the small invasive cribriform/ IDC pattern was found in the higher grade groups: 12 of 1116 (1.1%) of men in grade group 1, 79 of 444 (17.8%) in grade group 2, 77 of 163 (47.2%) in grade group 3, 31 of 83 (37.3%) in grade group 4 and 34 of 81 (42.0%) in grade group 5. All patients with the small cribriform/IDC pattern in grade group 1 had IDC without coinciding invasive cribriform growth.

In total, 47 of 1887 (2.5%) patients had the large cribriform growth pattern. The percentage of men with the large cribriform pattern increased per grade group: two of 444 (0.5%) men had the large cribriform pattern in grade group 2, 16 of 163 (9.8%) in grade group 3, 15 of 83 (18.1%) in grade group 4 and 14 of 81 (17.3%) men in grade group 5; no large cribriform pattern was observed among grade group 1 men. PSA levels were significantly higher (P < 0.02) in patients with the large cribriform pattern (median = 8.0 ng/ml; IQR = 5.8–17.5) than in men with the small cribriform pattern (median = 6.4 ng/ml; IQR = 4.2–11.9). Patients with the large cribriform growth were of similar (P = 0.39) age (median = 68.0 years; IQR = 65.0–72.0) as patients with only the small cribriform pattern (median = 67.8 years; IQR = 64.2–71.5).

SURVIVAL ANALYSIS

At follow‐up, 134 (7.1%) men developed metastasis after a median of 8.9 (IQR = 5.7–12.8) years, while 1123 (59.5%) patients died, including 123 (6.5%) men who died of prostate cancer (11.0% of all deaths). Metastasis occurred in 18 of 47 (38.3%) men with the large cribriform pattern, 59 of 233 (25.3%) with the small cribriform pattern and 57 of 1607 (3.5%) without cribriform pattern at biopsy, while 18 of 47 (38.3%), 58 of 233 (24.9%) and 47 of 1607 (2.9%) died of disease, respectively. In multivariable analyses grade group and PSA were independent prognostic parameters for both MFS and DSS (Table 2). Radical prostatectomy was the only treatment to be significantly (P = 0.004) associated with better DSS. Age, percentage positive biopsies and tumour length did not have a significant impact on MFS and DSS. Patients with the small cribriform pattern had shorter MFS [hazard ratio (HR) = 3.04; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.93–4.78; P < 0.001] and DSS (HR = 4.07; 95% CI = 2.51–6.62; P < 0.001) than men without the cribriform pattern. The large cribriform pattern was also associated with worse MFS (HR = 3.17; 95% CI = 1.68–5.99; P < 0.001) and DSS (HR = 4.13; 95% CI = 2.14–7.98; P < 0.001). Patients with large cribriform structures had similar MFS (P = 0.77) and DSS (P = 0.96) to those with the small cribriform pattern.

Table 2.

Metastasis‐free and disease‐specific survival

| Parameter | Metastasis‐free survival | Disease‐specific survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | – | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.740 | |

| PSA (log2) | 1.27 (1.10–1.47) | 0.001 | 1.20 (1.02–1.40) | 0.024 |

| Grade group | ||||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 | 2.05 (1.12–3.74) | 0.020 | 1.32 (0.68–2.55) | 0.411 |

| 3 | 2.83 (1.41–5.70) | 0.004 | 2.47 (1.19–5.11) | 0.015 |

| 4 | 3.59 (1.68–7.64) | 0.001 | 2.77 (1.25–6.17) | 0.012 |

| 5 | 4.48 (2.10–9.57) | <0.001 | 3.94 (1.81–8.59) | 0.001 |

| Perc posbx (log2) | 1.15 (0.79–1.67) | 0.480 | 1.20 (0.81–1.79) | 0.365 |

| Tumour mm (log2) | 1.14 (0.93–1.39) | 0.204 | 1.10 (0.89–1.35) | 0.380 |

| Cribriform | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Small | 3.04 (1.93–4.78) | <0.001 | 4.07 (2.51–6.62) | <0.001 |

| Large | 3.17 (1.68–5.99) | <0.001 * | 4.13 (2.14–7.98) | <0.001 * |

| Radical prostatectomy | 0.46 (0.11–1.99) | 0.302 | 0.38 (0.19–0.74) | 0.004 |

| Radiotherapy | 1.16 (0.28–4.81) | 0.842 | 0.94 (0.52–1.70) | 0.846 |

| Hormonal | – | – | ||

| Watchful waiting/active surveillance | 1.65 (0.37–7.47) | 0.513 | – | |

Perc posbx, percentage of positive biopsies; tumour mm, cumulative tumour length of all biopsies, in mm.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PSA, prostate‐specific antigen.

When using ‘small cribriform’ as reference, there was no statistical difference in metastasis‐free survival (MFS) (P = 0.77) and disease‐specific survival (DSS) (P = 0.96) for large cribriform.

Discussion

The adverse prognostic value of invasive cribriform and intraductal carcinoma in prostate cancer has been well established during the last decade. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Slightly different criteria for cribriform architecture have been used in various publications, particularly with regard to a minimal size threshold. 7 , 14 , 15 In a recent ISUP panel meeting, it was consented that cribriform architecture consisted of a contiguous epithelial proliferation in which the majority of tumour cells does not contact adjacent stroma and with visible intercellular lumina. 19 Specifically, no minimal size criterion was included in this consensus definition. Nevertheless, it has been shown in grade group 2 radical prostatectomy specimens that men with the large cribriform pattern had significantly worse clinical features and shorter BCRFS than those with a small cribriform architecture. 16 In fact, in that study no difference was present in grade group 2 tumours with small invasive cribriform or intraductal carcinoma and those without a cribriform growth pattern. These findings suggest that the large cribriform pattern is mainly responsible for adverse outcome and not any cribriform pattern per se. The aim of the current study was to determine whether such an effect was also present in a large cohort of prostate cancer biopsies with long‐term follow‐up. Here we show that small and large cribriform carcinomas on prostate cancer biopsies both had independent predictive value for MFS and DSS. Furthermore, patients with large cribriform structures did not have a worse outcome than men with a small cribriform carcinoma.

The current findings in biopsy specimens are not in agreement with our previous study among 420 grade group 2 radical prostatectomy specimens. In the prostatectomy cohort, we found that grade group 2 patients with the large cribriform pattern had significantly more frequent extraprostatic expansion and pelvic lymph node metastasis as well as shorter BCRFS than those with the small pattern. 16 This discrepancy can have several causes. First, recognition of the large cribriform pattern at biopsy seems less reliable than on surgical specimens. We defined the large cribriform pattern as a malignant cribriform lesion having at least twice the size of adjacent pre‐existent glands. While cribriform size is easily visualised in radical prostatectomy, it can be less well appreciated in 1‐mm thick biopsy specimens which will only sample a part of a large cribriform lesion. This is reflected by the frequency of the large cribriform pattern. While 34 of 420 (8.1%) grade group 2 radical prostatectomy specimens had the large cribriform pattern, it was observed in only two of 444 (0.5%) grade group 2 biopsies in the current study. Furthermore, three studies showed there is low sensitivity but relatively high specificity for identification of the cribriform pattern in matched biopsy and prostatectomy specimens. 20 , 21 , 22 Interestingly, Hollemans et al. found an overall false‐negative rate of 40% for identification of any cribriform carcinoma, while this decreased to 27% for the large cribriform pattern in diagnostic biopsies preceding radical prostatectomy. 21 In many of these men with the large cribriform pattern at operation, however, only the small cribriform pattern was present in the matched biopsy. Together, these studies suggest that about half of cribriform lesions are missed at biopsy due to sampling artefact, and that in the case of the large cribriform pattern in radical prostatectomies, often only the small cribriform is identified at preceding biopsy.

As far as we are aware, two studies have specifically compared the outcome of large and small cribriform pattern in grade group 2 prostate cancer patients. 16 , 23 Multivariable analysis in the radical prostatectomy study of Hollemans et al. showed that the large cribriform pattern was the only significant predictive variable for BCRFS, while the small cribriform pattern lost its significance. 16 Therefore, we hypothesise that the large cribriform pattern is clinically important but that its recognition is seriously hampered by sampling artefacts inherent to biopsies. This finding is in line with the grade group 2 biopsy study by Flood et al., who found that small and large cribriform patterns, as distinguished by ≤ 12 and > 12 punched‐out lumina, respectively, were both significantly associated with upgrading and extraprostatic expansion at subsequent radical prostatectomy. 23 Together, this underscores the importance of multimodal risk stratification of prostate cancer management; for instance, by including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results or molecular companion diagnostics. Patients with cribriform carcinoma at radical prostatectomy tend to have a higher PiRADS score than those without the cribriform pattern. 21 , 24 Furthermore, three companion diagnostic tests are commercially available for distinction of more aggressive grade group 2 prostate cancer patients, and some of these tests, at least in part, have been shown to reflect cribriform morphology. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28

The strength of this study is the use of a large well‐characterised prostate biopsy cohort with long‐term clinical follow‐up of more than 13 years. This allows for the analysis of detailed pathological features with strong and relevant clinical endpoints such as occurrence of metastasis and disease‐specific death. One inherent disadvantage of the use of samples with such long‐term follow‐up is that, at that time, state‐of‐the‐art clinical practice was different from the present. In the 1990s standard sextant biopsies were used, while current biopsy schemes often apply more systematic biopsies as well as MRI targeted biopsies. Together, this might have led to an underestimation of the presence of the large cribriform pattern in the current study. Furthermore, treatment modalities have been modified over the years with more common use of active surveillance in low‐risk patients who received active treatment two decades ago. Although the large cribriform architecture is believed to have a worse outcome than the small cribriform pattern, there is no consensus on the distinguishing features of large and small cribriform structures. In this study we defined large cribriform pattern as those structures exceeding twice the size of adjacent pre‐existent glands, which we also applied in our previous radical prostatectomy study. 16 This threshold is easy to apply, but is subjective. Application of other definitions of the large cribriform pattern, such as an exact‐sized cut‐off in μm or number of punched‐out lumina, will probably result in different distributions and clinical outcomes. Furthermore, interobserver variability on assessment of the cribriform pattern could also affect the outcome of different studies. 29 , 30 Finally, we did not perform basal cell immunohistochemistry in each cribriform biopsy to distinguish invasive from intraductal carcinoma, which might have affected definitive grade group assignment in a small number (<2%) of cases. 31

In conclusion, have we shown that both small and large cribriform patterns are associated with shorter metastasis‐ and disease‐specific‐free survival. These results support the notion that men with the cribriform growth pattern should not be considered for active surveillance. Furthermore, we found that there was no difference in survival probabilities in the large cribriform versus the small cribriform pattern, and therefore does not require differentiation on biopsies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgements

None.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Rawla P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World. J. Oncol. 2019; 10; 63–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E et al. Eau‐eanm‐estro‐esur‐siog guidelines on prostate cancer – 2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 2021; 79; 243–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lam TBL, MacLennan S, Willemse PM et al. EAU‐EANM‐ESTRO‐ESUR‐SIOG Prostate Cancer Guideline Panel consensus statements for deferred treatment with curative intent for localised prostate cancer from an international collaborative study (detective study). Eur. Urol. 2019; 76; 790–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB et al. The 2014 International Society Of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016; 40; 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Leenders G, van der Kwast TH, Grignon DJ et al. The 2019 International Society Of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on grading of prostatic carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020; 44; e87–e99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epstein JI, Amin MB, Fine SW et al. The 2019 Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) White Paper on contemporary grading of prostate cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021; 145; 461–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iczkowski KA, Torkko KC, Kotnis GR et al. Digital quantification of five high‐grade prostate cancer patterns, including the cribriform pattern, and their association with adverse outcome. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011; 136; 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kweldam CF, Kummerlin IP, Nieboer D et al. Disease‐specific survival of patients with invasive cribriform and intraductal prostate cancer at diagnostic biopsy. Mod. Pathol. 2016; 29; 630–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kweldam CF, Wildhagen MF, Steyerberg EW, Bangma CH, van der Kwast TH, van Leenders GJ. Cribriform growth is highly predictive for postoperative metastasis and disease‐specific death in Gleason score 7 prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2015; 28; 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iczkowski KA, Paner GP, Van der Kwast T. The new realization about cribriform prostate cancer. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2018; 25; 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong F, Yang P, Wang C et al. Architectural heterogeneity and cribriform pattern predict adverse clinical outcome for Gleason grade 4 prostatic adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013; 37; 1855–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kryvenko ON, Gupta NS, Virani N et al. Gleason score 7 adenocarcinoma of the prostate with lymph node metastases: analysis of 184 radical prostatectomy specimens. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013; 137; 610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo CC, Epstein JI. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy: Histologic features and clinical significance. Mod. Pathol. 2006; 19; 1528–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trudel D, Downes MR, Sykes J, Kron KJ, Trachtenberg J, van der Kwast TH. Prognostic impact of intraductal carcinoma and large cribriform carcinoma architecture after prostatectomy in a contemporary cohort. Eur. J. Cancer 2014; 50; 1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Leenders G, Verhoef EI, Hollemans E. Prostate cancer growth patterns beyond the Gleason score: entering a new era of comprehensive tumour grading. Histopathology 2020; 77; 850–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hollemans E, Verhoef EI, Bangma CH et al. Large cribriform growth pattern identifies ISUP grade 2 prostate cancer at high risk for recurrence and metastasis. Mod. Pathol. 2019; 32; 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roobol MJ, Schroder FH. European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer: achievements and presentation. BJU Int. 2003; 92; 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ et al. Screening and prostate‐cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009; 360; 1320–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Kwast TH, van Leenders GJ, Berney DM et al. ISUP consensus definition of cribriform pattern prostate cancer. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021; 45; 1118–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ericson KJ, Wu SS, Lundy SD, Thomas LJ, Klein EA, McKenney JK. Diagnostic accuracy of prostate biopsy for detecting cribriform Gleason pattern 4 carcinoma and intraductal carcinoma in paired radical prostatectomy specimens: implications for active surveillance. J. Urol. 2020; 203; 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollemans E, Verhoef EI, Bangma CH et al. Concordance of cribriform architecture in matched prostate cancer biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens. Histopathology 2019; 75; 338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Masoomian M, Downes MR, Sweet J et al. Concordance of biopsy and prostatectomy diagnosis of intraductal and cribriform carcinoma in a prospectively collected data set. Histopathology 2019; 74; 474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flood TA, Schieda N, Keefe DT et al. Utility of Gleason pattern 4 morphologies detected on transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)‐guided biopsies for prediction of upgrading or upstaging in Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 prostate cancer. Virchows Arch. 2016; 469; 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greenland NY, Cowan JE, Zhang L et al. Expansile cribriform Gleason pattern 4 has histopathologic and molecular features of aggressiveness and greater risk of biochemical failure compared to glomerulation Gleason pattern 4. Prostate 2020; 80; 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor AS, Morgan TM, Wallington DG, Chinnaiyan AM, Spratt DE, Mehra R. Correlation between cribriform/intraductal prostatic adenocarcinoma and percent Gleason pattern 4 to a 22‐gene genomic classifier. Prostate 2020; 80; 146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kristiansen G. Markers of clinical utility in the differential diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2018; 31; S143–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cucchiara V, Cooperberg MR, Dall'Era M et al. Genomic markers in prostate cancer decision making. Eur. Urol. 2018; 73; 572–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenland NY, Zhang L, Cowan JE, Carroll PR, Stohr BA, Simko JP. Correlation of a commercial genomic risk classifier with histological patterns in prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2019; 202; 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kweldam CF, Nieboer D, Algaba F et al. Gleason grade 4 prostate adenocarcinoma patterns: an interobserver agreement study among genitourinary pathologists. Histopathology 2016; 69; 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah RB, Cai Q, Aron M et al. Diagnosis of ‘cribriform’ prostatic adenocarcinoma: an interobserver reproducibility study among urologic pathologists with recommendations. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021; 11; 3990–4001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rijstenberg LL, Hansum T, Hollemans E et al. Intraductal carcinoma has a minimal impact on grade group assignment in prostate cancer biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens. Histopathology 2020; 77; 742–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.