Abstract

Tangeretin, 4′,5,6,7,8-pentamethoxyflavone, is one of the major polymethoxyflavones (PMFs) existing in citrus fruits, particularly in the peels of sweet oranges and mandarins. Tangeretin has been reported to possess several beneficial bioactivities including anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and neuroprotective effects. To achieve a thorough understanding of the biological actions of tangeretin in vivo, our current study is designed to investigate the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, distribution and excretion of tangeretin in rats. After oral administration of 50 mg/kg bw tangeretin to rats, the Cmax, Tmax and t1/2 were 0.87 ± 0.33 μg/mL, 340.00 ± 48.99 min and 342.43 ± 71.27 min, respectively. Based on the area under the curves (AUC) of oral and intravenous administration of tangeretin, calculated absolute oral bioavailability was 27.11%. During tissue distribution, maximum concentrations of tangeretin in the vital organs occurred at 4 or 8 h after oral administration. The highest accumulation of tangeretin was found in the kidney, lung and liver, followed by spleen and heart. In the gastrointestinal tract, maximum concentrations of tangeretin in the stomach and small intestine were found at 4 h, while in the cecum, colon and rectum, tangeretin reached the maximum concentrations at 12 h. Tangeretin excreted in the urine and feces was recovered within 48 h after oral administration, concentrations were only 0.0026% and 7.54%, respectively. These results suggest that tangeretin was mainly eliminated as metabolites. In conclusion, our study provides useful information regarding absorption, distribution, as well as excretion of tangeretin, which will provide a good base for studying the mechanism of its biological effects.

Keywords: Tangeretin, Oral bioavailability, Pharmacokinetics, Tissue distribution, Excretion

1. Introduction

Flavonoids are ubiquitously in fruits, cereals, seeds and vegetables, as well as some beverages including wine and tea. The typical structure of flavonoids is a fifteen-carbon skeleton consisting of two phenyl rings. Many in vitro and in vivo studies have reported that flavonoids possess numerous health benefits [1–3]. Polymethoxyflavones (PMFs) are a unique group of methylated flavonoids existing exclusively in citrus fruits, particularly the peel of sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis) and mandarins (Citrus reticulata). The contents and types of PMFs vary depending on the different varieties of citrus species. In some countries, orange peel is used as traditional medicine for relieving skin inflammation and stomach upset, as well as muscle pain. Over the past few years, numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated that PMFs are the major bioactive flavonoids in citrus peel, possessing several biological activities, including anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and neuroprotective properties [4–7].

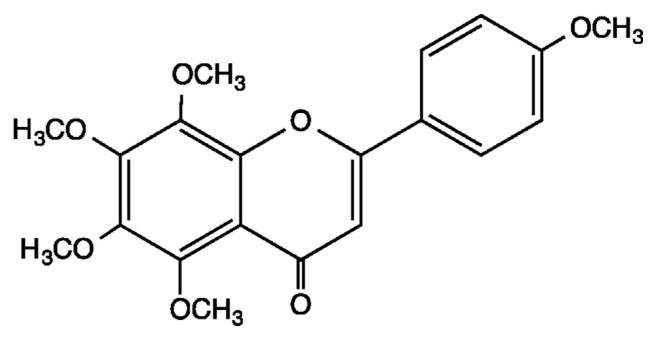

Tangeretin is one of the most abundant PMFs in citrus peel (Fig. 1). Concentrations vary depending on the different citrus varieties. For example, among 45 citrus fruits, the concentrations of tangeretin in the peel ranged from 0.1 to 174 mg/100 g (fresh weight), while its concentration in commercial citrus beverages was 0.08–0.60 mg/L [8,9]. Numerous studies have reported tangeretin to possess a broad spectrum of biological activities [10–16]. Among 27 citrus flavonoids, tangeretin exhibited potent anti-proliferative effects against lung and gastric carcinoma, melanoma and leukemia cell growth [14]. A recent study reported that tangeretin effectively suppressed glioblastoma cell growth in a dose- and time-dependent manner [17]. Tangeretin treatment arrested glioblastoma cells at G2/M phase by modulating phosphatase and tensin homolog and cyclin-D and ccd-2 mRNA expression. Additionally, tangeretin suppressed lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and decreasing diacylglycerol acyltransferase and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein [18]. Recently a similar study revealed that supplementation of 1% PMF containing tangeretin for 8 weeks significantly reduced triacylglycerol, body weight and the relative weights of white adipose tissue pads in high cholesterol diet-fed hamsters [16]. These effects were associated with decreased fatty acid synthase, sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c and increased lipoprotein lipase. Finally, tangeretin has shown neuroprotective effects through alleviation of the inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated microglial cells [15,19].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of tangeretin.

PMFs have attracted much attention due to their high oral bioavailabilities when compared to hydroxyflavones. The high oral bioavailability of PMFs is due to the lipophilic nature of structure’s multiple methoxy groups. An early investigation revealed that PMFs, including tangeretin and nobiletin, exhibited higher anti-proliferative effects against squamous cell growth in both a dose- and time-dependent manner as compared to quercetin and taxifolin [20]. These higher activities found in PMFs resulted from the methoxy groups, leading to a decrease of hydrophilicity, followed by enhanced cellular uptake.

Many in vitro studies indicated flavonoids possess different bioactivities; however, poor bioavailability may make them largely ineffective in vivo [21,22]. Since numerous in vitro studies report tangeretin exhibits a broad spectrum of biological activities, absorption levels are of special interest. Previous studies on pharmacokinetics and excretion of tangeretin have been conducted [23,24]. However, a comprehensive study regarding the pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, plus excretion of tangeretin has not been fully investigated. In current study, we first used SD rats as an animal model to determine the oral bioavailability of tangeretin, and then evaluated tangeretin distribution in the tissues, as well as tangeretin excretion in urine and feces.

2. Meterials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Tangeretin was isolated from citrus peel extract and purified using column chromatography. The purity of tangeretin was determined above 95% by HPLC using an absorbance wavelength of 270 nm. Hesperetin was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and the purity was above 98%. Methanol and sodium chloride were sourced from Mallinckrodt Baker (Center Valley, PA, USA). Ethyl acetate, ethanol, formic acid, dimethyl sulfoxide and Tween 80 were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Animals and diets

Healthy, 6-week-old, male SD rats purchased from BioLASCO (Nangang, Taipei, Taiwan) were used to investigate the pharmacokinetics, distribution and excretion of tangeretin. All animals were housed in a controlled environment (22 ± 3 °C, 40–60% relative humidity, 12-h light-dark cycle, 0700–1900) and fed with a commercial diet (LabDiet, 5001, Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) with distilled water ad libitum throughout the experiment. The experimental protocol was approved by the National Laboratory Animal Center (Nangang, Taipei, Taiwan). Care of the animals was in compliance with the Taiwan Government’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experimental protocol was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use committee, National Taiwan University.

2.3. Pharmacokinetics experiment

Before initiation of the pharmacokinetics study, the animals were divided into two groups, each group containing six rats. The animals were fasted overnight, but had free access to water before the experiment. For the first treatment group, rats were orally administered 50 mg/kg tangeretin using oral gavage. For the second treatment group, rats were injected intravenously with tangeretin (5 mg/kg) through a femoral vein. Tangeretin was dissolved in standard saline containing 10% Tween 80 and 20% dimethyl sulfoxide at doses of 5 and 50 mg/mL for intravenous injection and oral administration, respectively. After oral administration of tangeretin, an aliquot of blood was collected from the tail vein of the same animal at 0 (pre-dose), 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 360, 480, 600, 720 and 1440 min. The scheduled time points for the intravenous injection group were 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240, 300, 360 and 720 min. After centrifugation at 2800g for 10 min at 4 °C, 100 μL plasma sample was mixed with 1 mL ethyl acetate containing 1 μg/mL hesperetin (internal standard) for protein precipitation. After centrifugation at 8000g for 10 min at 4 °C, supernatant was collected and the solvent was evaporated using a stream of nitrogen gas. Dried supernatant was reconstituted in 100 μL methanol and then filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon filter prior to LC-MS analysis. For preparation of the calibration curve, blank plasma was spiked with different concentrations of tangeretin and 1 mL ethyl acetate was added for protein precipitation. The concentration of tangeretin in blank plasma ranged from 0.005 to 2.5 μg/mL.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the WinNonlin Software (Certara, Princeton, NJ, USA). The area under the curve (AUC) is the integral of the plasma concentration of an altered drug against an interval of definite time. The absolute oral bioavailability was calculated by comparing the AUCs of tangeretin after oral and intravenous administration according to Equation (1):

| (1) |

The AUCpo and AUCiv correspond to the areas under concentration–time curves after oral and intravenous administration, respectively. Dosepo and Doseiv correspond to the actual doses received via oral and intravenous administration.

2.4. Distribution experiment

In the distribution experiment, rats were orally administered 50 mg/kg tangeretin, then three rats were sacrificed for each 4, 8, 12, 24 and 48 h time period. Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture and a plasma sample obtained after centrifugation. The heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, stomach, intestine, cecum, colon and rectum were excised, rinsed with saline and blotted dry. To estimate the recovery of tangeretin, undigested food containing tangeretin were retained in the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract. Plasma and tissue samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

For extraction, rat tissue was homogenized in standard saline using a Polytron homogenizer (Luzern, Switzerland). One hundred microliters of hesperetin (100 μg/mL) were added to the tissue homogenate, which was then mixed with ethyl acetate (1:2, v/v) using a shaker for 30 min. After centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C, supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and the residue was extracted again using ethyl acetate. Both supernatants were combined and solvent was evaporated using a SpeedVac Concentrator (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The dried supernatant was reconstituted in 1 mL methanol and filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon filter prior to HPLC analysis. To understand the conversion of tangeretin in vivo at different time intervals, the weight percentage of tangeretin was also calculated (% = [amount of tangeretin in the tissue/amount of tangeretin by oral gavage] × 100).

2.5. Excretion experiment

For the excretory experiment, six rats were orally administered with 50 mg/kg tangeretin and housed individually in metabolic cages. Urine and fecal samples were collected at the following time intervals: 0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12–24, 24–36 and 36–48 h after oral administration of tangeretin. The volume of urine and the weight of fecal samples from each time point were measured before extraction. The fecal samples were lyophilized before pulverization. The pulverized feces were mixed with 100 μL hesperetin (100 μL/mL) and then extracted with ethyl acetate (1:10, w/v) using a shaker for 30 min. After centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and then the residue was extracted again using ethyl acetate. The solvent from the combined supernatant was removed using a SpeedVac Concentrator. Urine samples were mixed with ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v, containing 10 μg hesperetin as internal standard) using a shaker for 30 min and subsequently centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Then, supernatant was collected and the urine was again extracted with ethyl acetate. The solvent from the supernatant was removed using a SpeedVac Concentrator. Dried supernatant from both urine and fecal samples was reconstituted in 1 mL methanol and then filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon filter prior to LC-MS analysis. A procedure similar to that for plasma samples was used to prepare the calibration curve in urine and fecal samples. The spiked concentrations of tangeretin in blank urine and feces ranged from 0.05 to 250 μg/mL. The concentration of tangeretin in the urine and feces were determined using the calibration curve obtained from spiking of blank urine samples with tangeretin. Total amounts of tangeretin excreted from urine and feces were calculated based on the volume of urine and the weight of feces.

2.6. Determination of tangeretin in tissue

Tangeretin was separated using a Synergi Hydro-RP C18 column (2 × 50 mm, 4 μm particle size) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) coupled with an ultraviolet–visible detector at a wavelength of 270 nm. The flow rate was 0.8 mL/min and the injection volume was 20 μL. The mobile phase consists of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and 0.1% formic acid in methanol (B). The elution program was set as follows: 0–4 min, 10–100% B; 4–6 min, 100% B; 6–6.2 min, 100–10% B; 6.2–9 min, 10% B.

2.7. Determination of tangeretin in plasma, urine and feces

For plasma samples, the method was adapted as previously described [25]. Quantification was achieved using an LC-MS system consisting of a Jasco PU-2080 pump (Tokyo, Japan), a Schambeck SFD autosampler (Bad Honnef, Germany) and a Thermo LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source. The column and elution program were the same method as used for determining tangeretin in rat tissues. The flow rate was set at 0.2 mL/min and the injection volume was 2 μL. Quantification of tangeretin was carried out using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in positive ion mode according to the reaction m/z 373 → 358. The global MS parameters were set as follows: Capillary temperature, 310 °C; Sheath gas flow rate, 20 arbitrary unit (a.u.); Aux gas flow rate, 20 a.u.; source voltage, 5 kV; capillary voltage, 16 V.

For urine and fecal samples, chromatographic separation was carried out using a Waters Atlantis T3 C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 5 μm particle size) (Milford, MA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and 0.1% formic acid in methanol (B). The elution grogram was set as follows: 0–20 min, 10–100% B; 20–27 min, 100% B; 27–28 min, 100–10% B; 28–40 min, 10% B. The injection volume was 5 μL and the flow rate was set at 0.2 mL/min tangeretin was quantified using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in positive ion mode according to the reaction m/z 373 → 358. Global MS parameters were the same as the analytical method for the plasma samples.

3. Results

3.1. Method validation

To determine the concentration of tangeretin in rat plasma, a standard curve of tangeretin was prepared using blank rat plasma and adding different concentrations of tangeretin. The calibration curve was plotted using the peak area of tangeretin/internal standard peak area against the concentration of tangeretin/concentration of internal standard. The calibration curve in the range of 0.005–2.5 μg/mL showed excellent linearity and the correlation coefficient R2 was 0.998. For precision, six replicates of seven different concentration levels within the calibration curve were analyzed within six days, and the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated. Either intra-day or inter-day precision expressed as the percentage of CV was lower than 15% at all tested concentrations (Table S1). It should be noted that variations for either intra-day or inter-day lower than 15% are acceptable [26]. To measure the systematic error of our analytical method, accuracy was also calculated to determine any difference between the measured value and the true value. Similar to results from precision measurement, the percentage of bias ranged from −0.15–9.97%. Acceptable accuracy of the analytical method should be within ±15% [26]. The limit of quantification (LOQ) and limit of detection (LOD) of our method were 0.0287 and 0.005 μg/mL, respectively. Collectively, this validated LC-MS method was suitable for determination of tangeretin in plasma samples. Similar results were found for urine and fecal samples. The calibration curve prepared for the urine and fecal samples ranged from 0.005 to 2.5 μg/mL, which showed excellent linearity with the correlation coefficient R2 > 0.995.

The distribution experiment used an HPLC-UV method to determine tangeretin in rat tissues. The calibration curve showed excellent linearity and the correlation coefficient R2 was above 0.999. The LOQ and LOD of this HPLC method were 0.39 μg/mL and 0.12 μg/mL, respectively. For method validation, the CV values in all tested concentrations were lower than 12%, while the bias values were within ±7% (Table S2). Meanwhile, in the recovery experiment, different concentrations of tangeretin were spiked into plasma and the blank tissues, including heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney stomach, small intestine, cecum, large intestine and rectum (Table S3). In rat tissues, spiked recoveries of tangeretin at the lowest concentration (1 μg/mL) ranged from 76.56 to 99.83%, whereas at the high concentration (10 μg/mL), the recoveries were above 90% in all tissues. Based on these results, our current method was suitable for quantification of tangeretin in rat tissues.

3.2. Pharmacokinetic parameters and oral bioavailability in rat

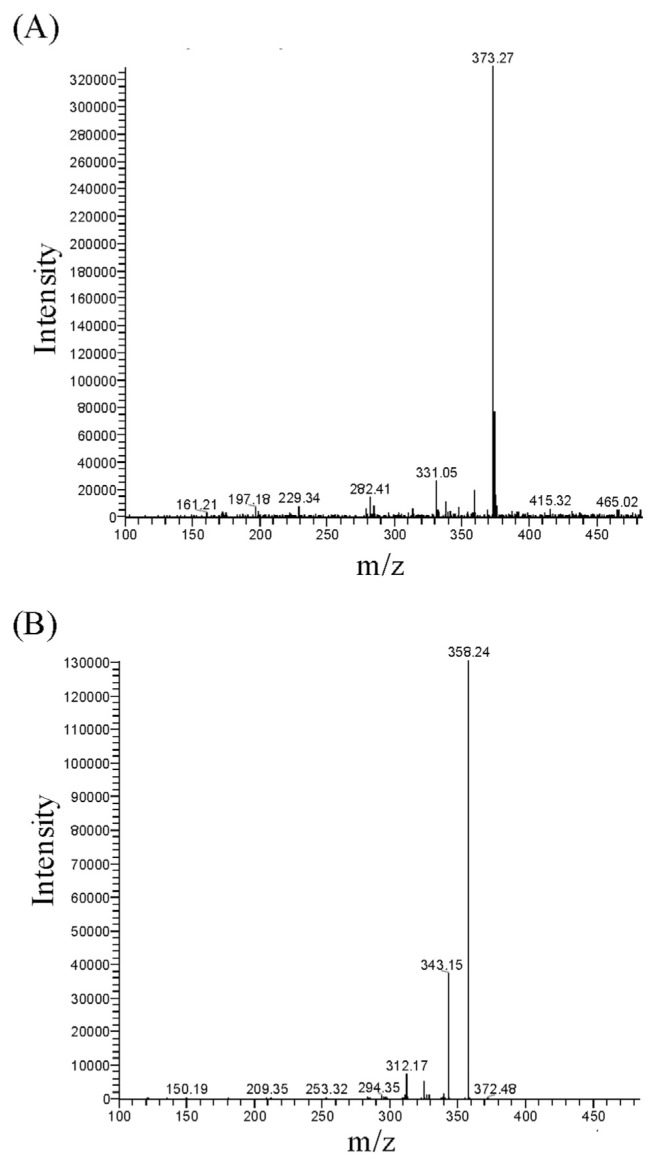

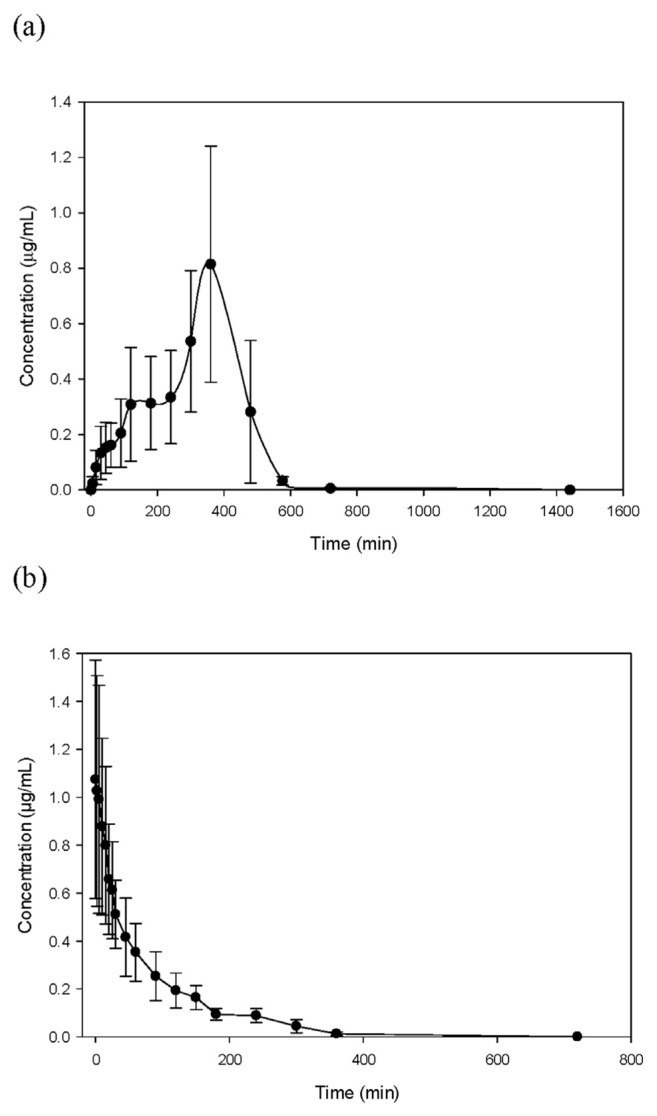

To determine the oral bioavailability of tangeretin, rats were either orally or intravenously administered with tangeretin. The MS/MS spectra of tangeretin in rat plasma after oral administration of tangeretin (50 mg/kg), with mass transitions of m/z 373 [M + H]+ → m/z 358 [M + H – CH3]+ → m/z 343 [M + H – CH3 – CH3]+, are shown in Fig. 2. After administration of tangeretin, blood samples were collected at different time intervals and then analyzed using LC-MS with the MRM mode. The concentration–time profile and pharmacokinetic parameters of tangeretin are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 3. After oral and intravenous administration of tangeretin, the maximum concentrations of tangeretin were 0.87 ± 0.33 and 1.11 ± 0.41 μg/mL, respectively; and the elimination half-lives were 342.43 ± 71.27 and 69.87 ± 15.72 min, respectively. The AUC, one important parameter for pharmacokinetic studies, represents the total drug exposure integrated over time. The AUC values of oral and intravenous administration of tangeretin were 213.78 ± 80.63 and 78.85 ± 7.39 min μg/mL, respectively. The calculated absolute oral bioavailability (F) of tangeretin was 27.11% in rats, according to Equation (1).

Fig. 2.

Mass spectra of tangeretin in rat plasma. (A) Fullscan mass spectrum of tangeretin (m/z 373 [M + H]+) and (B) its product ions (MS/MS chromatograms; m/z 373 → m/z 358).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of tangeretin in rat after oral or intravenous administration of tangeretin.

| Parameters | Oral (50 mg/kg bw) | Intravenous (5 mg/kg bw) |

|---|---|---|

| Tmax (min) | 340.00 ± 48.99 | – |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 1.07 ± 0.49 |

| t1/2 (min) | 342.43 ± 71.27 | 69.87 ± 15.72 |

| AUC (min · μg/mL) | 213.78 ± 80.63 | 78.85 ± 7.39 |

| AUC/Dose (min/L) | 4.28 ± 1.61 | 15.77 ± 1.48 |

| F (%) | 27.11 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD from six rats. Cmax, peak plasma concentration (μg/mL plasma), tmax; time to reach Cmax; t1/2, elimination half-life; AUC0–24, area under the concentration–time curve; F, absolute oral bioavailability.

Fig. 3.

Concentration–time profiles of tangeretin in rat plasma following (a) oral administration of 50 mg/kg tangeretin or (b) intravenous injection of 5 mg/kg tangeretin. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from six rats.

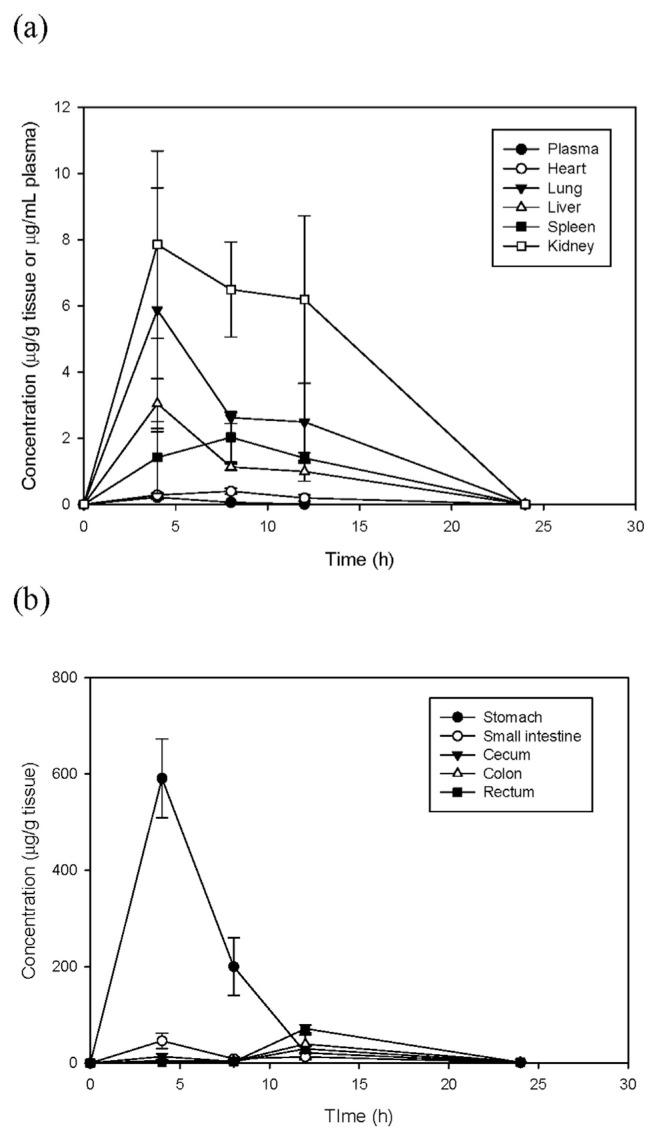

3.3. Distribution of tangeretin in rat

In the distribution study, tangeretin concentrations were measured in tissues and plasma within 48 h after administrated to rats. The concentration–time profiles of tangeretin in the vital organs and gastrointestinal tract are shown in Fig. 4. Tangeretin was widely distributed amongst the organs, reaching a maximum level within 4–8 h, and was rarely detected after 12 h. Among the organs, the highest concentration of tangeretin was in the kidney and lung with a Cmax of 7.85 and 5.88 μg/g, respectively. In order to estimate the recovery of unaltered tangeretin distributed in the gastrointestinal tract at different time intervals, the content of the stomach, cecum, small intestine, colon and rectum were intact after sacrifice. After oral administration to rats, unaltered tangeretin in gastrointestinal contents and tissues was homogenized, extracted and then analyzed at different time intervals. Maximum concentrations of tangeretin in the stomach and small intestine were found at 4 h, whereas in the cecum, colon and rectum, the highest concentrations were found at 12 h (Fig. 4b). Weight percentages of tangeretin distributed in the tissues and gastrointestinal tracts are listed in Table 2. After oral administration, only 24.27% unchanged tangeretin existed in vital organs and the gastrointestinal tract at 4 h, indicating approximately 76% of dosed tangeretin was absorbed or retained in the gastrointestinal tract in the form of tangeretin metabolites. After 4 h, less than 9% tangeretin was accumulated in the tissues or retained in the digestive tract.

Fig. 4.

Concentration–time profiles of tangeretin in (a) vital organs and (b) different regions of the gastrointestinal tract after oral administration of 50 mg/kg tangeretin. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from six rats.

Table 2.

Weight percentage of dosed tangeretin in rat tissues after oral administration of tangeretin.

| Time (h) | Tangeretin (% of dose) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Plasma | Heart | Lung | Liver | Spleen | Kidney | Stomach | Small intestine | Cecum | Colon | Rectum | Total | |

| 4 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.002 ± 0.000 | 0.042 ± 0.021 | 0.030 ± 0.083 | 0.007 ± 0.005 | 0.120 ± 0.005 | 20.033 ± 3.203 | 3.097 ± 0.918 | 0.579 ± 0.226 | 0.081 ± 0.022 | 0.008 ± 0.006 | 24.265 ± 4.051 |

| 8 | 0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.003 ± 0.000 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.010 ± 0.014 | 0.010 ± 0.006 | 0.116 ± 0.028 | 3.943 ± 1.512 | 0.593 ± 0.243 | 0.086 ± 0.066 | 0.048 ± 0.047 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 4.930 ± 1.840 |

| 12 | 0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.018 ± 0.007 | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.067 ± 0.052 | 0.420 ± 0.256 | 0.746 ± 0.350 | 0.927 ± 0.164 | 0.544 ± 0.248 | 0.521 ± 0.110 | 3.333 ± 0.925 |

| 24 | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | 0.026 ± 0.013 | 0.059 ± 0.017 | 0.040 ± 0.018 | 0.031 ± 0.012 | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 0.170 ± 0.027 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). N.D: not detected. Weight percentage of tangeretin (% of dose) = [The amount of tangeretin in the tissue (mg)/the amount of tangeretin by oral administration (mg)] × 100%. The amount of tangeretin by oral administration (mg) = 50 mg/kg bw × body weight of each rat.

3.4. Excretion of tangeretin in rat

To evaluate the elimination of tangeretin in rats, tangeretin concentrations were measured within 48 h after oral administration of 50 mg/kg tangeretin and the results are shown in Table 3. The excretion profile revealed that tangeretin in urine reached a maximum peak at 0–4 h period, whereas only 0.26 μg tangeretin was excreted. After 12 h, the recovery of tangeretin in urine was relatively low. By the 48 h period, only 0.4 μg tangeretin was excreted in the urine, equaling to 0.0026% of the administered dose. In the feces, the concentration of tangeretin reached a maximum level by the 8–12 h period (Table 3). The amount of tangeretin excreted at 8–12 and 12–24 h were 377.34 and 712.12 μg, respectively. After oral administration of 50 mg/kg tangeretin to rats, 7.54% was excreted in unaltered form in feces within the 48 h period.

Table 3.

Urinary and fecal excretion of tangeretin during each time interval after oral administration of tangeretin.

| Time (h) | Urine | Feces | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Conc. (μg/mL) | Amount (μg) | Conc. (μg/g) | Amount (μg) | |

| 0–4 | 0.0386 ± 0.0178 | 0.2691 ± 0.1678 | N.D | N.D |

| 4–8 | 0.0214 ± 0.0121 | 0.0778 ± 0.0429 | 2.40 ± 1.74 | 3.62 ± 3.11 |

| 8–12 | 0.0055 ± 0.0028 | 0.0298 ± 0.0131 | 243.16 ± 112.05 | 377.34 ± 298.82 |

| 12–24 | 0.0010 ± 0.0004 | 0.0152 ± 0.0057 | 184.74 ± 48.70 | 712.12 ± 157.71 |

| 24–36 | 0.0006 ± 0.0004 | 0.0061 ± 0.0042 | 26.86 ± 11.21 | 97.70 ± 37.16 |

| 36–48 | 0.0005 ± 0.0001 | 0.0083 ± 0.0025 | 1.36 ± 0.48 | 6.54 ± 3.09 |

| Total | – | 0.4062 ± 0.1987 | – | 1197.33 ± 307.43 |

| % of dosing | – | 0.0026 ± 0.0012 | – | 7.54 ± 1.89 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). The given dose was 50 mg/kg. The amount of tangeretin by oral administration (mg) = 50 mg/kg bw × body weight of each rat.

4. Discussion

In current study, we developed a validated LC-MS/MS method to determine tangeretin in plasma. Due to the low UV sensitivity of PMFs, several studies have developed different LC-MS methods for investigation of pharmacokinetics [23,25,27,28]. To investigate absorption of tangeretin, we measured the concentrations of tangeretin in rat plasma at different time intervals. After oral administration of tangeretin to rats, the Tmax and Cmax were 340.00 ± 48.99 and 0.87 ± 0.33 μg/mL, respectively. A similar study found concentrations of tangeretin in rat plasma to be 0.49 μg/mL at 1 h after oral gavage of 50 mg/kg bw tangeretin and gradually decreased to 0.16 μg/mL by 8 h [23]. In addition, the maximum concentration of tangeretin in the intravenous injection group was 4.5 μg/mL, occurring at 0.5 h. However, our current data showed that the Cmax of tangeretin was only 1.11 μg/mL after intravenous injection. This discrepancy was due to the differences in administered doses. Next, we calculated the absolute oral bioavailability of tangeretin in rats to be 27.11%. In comparison with the oral availabilities of other PMFs, our recent study also evaluated the absolute oral bioavailability of 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone in rats. The Cmax and Tmax of 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone were 0.79 μg/mL and 190 min after oral administration, respectively. Based on the AUCs of oral and intravenous administration of 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone, the oral bioavailability was estimated as 14.3%, which was lower than tangeretin [25]. The oral bioavailabilities of PMFs may vary depending on the position or number of the methoxy groups. Previously, the rate of intestinal absorption of PMFs was studied in the Caco-2 cells [29]. The apparent permeability of 5,7,4′-trimethoxyflavone was higher than that from 7-methoxyflavone, 7,4′-methoxyflavone and 5,7-methoxyflavone suggesting more methoxy groups accelerated cellular permeability in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Moreover, oral bioavailabilities of 5,7-dimethylflavone, 5,7,4′-trimethoxyflavone and 3,5,7,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone in the Kaempferia parviflora extract were also studied in rats [30]. After oral and intravenous administration of K. parviflora extract to rats, the oral bioavailability of 3,5,7,3′,4′-pentam-ethoxyflavone was 3.32%, higher than that from 5,7-dimethylflavone and 5,7,4′-trimethoxyflavone. Tangeretin is a pentamethoxyflavone exhibiting higher oral bioavailability than 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone in rats, at least in part, due to its higher number of methoxy groups. Since methoxy groups greatly affect the bioavailability of methoxyflavones in vivo, it is noteworthy to compare the absorption of PMFs with unmethylated flavones. In Caco-2 human intestinal cells, the permeability of methoxylated flavones was approximately 5- to 8-fold higher than unmethylated flavones [29]. In a pharmacokinetic study, the same research group compared oral absorption of chrysin and 5,7-dimethoxyflavone in rats [31]. The AUC of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone in plasma was 58.8 μg/ mL·min, whereas no chrysin could be detected at any time-point. Their findings demonstrated that methylation greatly improved the oral bioavailability of flavones.

In the distribution results, tangeretin was widely distributed in the organs and gastrointestinal tract after a single dose of 50 mg/kg bw tangeretin was administered. We found that in rats, tangeretin was most concentrated in the kidney, lung and liver. In a Parkinson’s disease model, the rats were orally administered tangeretin (20 mg/kg bw/day) for 4 days prior to unilateral infusion of the dopaminergic neurotoxin, 6-hydroxydopamine [32]. One week after injection with 6-hydroxydopamine, the rats were sacrificed and tangeretin was measured in the peripheral organs and brain. Among the organs, the highest concentration of tangeretin was found in the liver, while the heart and lung contained similar concentrations, and the kidney and spleen contained the lowest concentrations. However, based on our results, the accumulation of tangeretin in the tissues was in descending order as follows: kidney > lung > liver > spleen > heart. This discrepancy may result from the different experimental design. Similarly, tissue distribution of different PMFs have been previously reported. After oral administration of 67.1 μg/kg nobiletin to rats, significant amounts of nobiletin were accumulated in the liver and kidney [33]. In addition, a recent study investigated tissue distribution of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone in mice [34]. Among peripheral organs, the AUCs of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone were found in descending order as follows: liver > kidney > spleen > heart > lung. However, Walle et al. reported that 5,7-dimethoxyflavone was most accumulated in liver > lung > kidney [31]. Collectively, PMFs typically accumulate most in liver and kidney, possibly because these are well-perfused organs [34]. It is worthy to note that significant amounts of tangeretin accumulated in the liver might be due to the multiple methoxy groups. In either pooled liver S9 fractions or human hepatocytes, 5,7-dimethoxyflavone and 3′,4′-dimethoxyflavone were metabolically stable, whereas galangin disappeared rapidly due to extensive glucur-onidation and sulfation [35].

In this study, we also investigated distribution of tangeretin in the digestive tract of rats. The Cmax of tangeretin in the digestive tract was relatively higher than that from the organs. Similar results were also found in tissue distribution of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone [34]. The Cmax and AUC of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone in the intestine were calculated as 6850 ng/g and 18,600 ng/g respectively, relatively higher than that in the liver, kidney, brain, spleen, heart, and lung. In 2002, Murakami et al. used SD rats as a model to study absorption, tissue distribution and metabolism of nobiletin [33]. In the digestive tract, concentrations of nobiletin in the stomach mucous membrane and muscularis were markedly higher than that from luteolin at 1 h after oral administration. These results provided crucial evidence that nobiletin may be absorbed into circulating blood through stomach muscularis. The localization of nobiletin in the mucous membrane and muscularis was due to its high hydrophobicity. In accordance with these results, our current study showed a significant amount of tangeretin was concentrated in the stomach as compared to the small intestine and large intestine. Although the high concentration of tangeretin in stomach was partly due to the undigested tangeretin retained in the lumen, our pharmacokinetic results revealed that tangeretin can be detected in plasma within 30 min after oral administration. Collectively, our pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution results implied that, like nobiletin, tangeretin might be absorbed through stomach tissue. To date, demethylation and conjugation have been identified as the two metabolic pathways of PMFs [5,23,24]. In rat liver microsomes, tangeretin was metabolized to 4′-hydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone and 3′,4′-dihydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone [36]. In intestinal metabolism, PMFs were also biotransformed to various demethylated metabolites by gut bacteria [37,38]. Using weight percentages of tangeretin distributed in vital organs and the digestive tract, we found that only 24% of tangeretin were detected in the organs and digestive tract at 4 h after oral administration, indicating that the approximately 76% of tangeretin was absorbed or retained in the lumen of the digestive tract as metabolites, such as demethylated derivatives of tangeretin.

To investigate the elimination of tangeretin in rats, tangeretin was measured in the urine and fecal samples within 48 h after oral administration. At different time intervals, tangeretin in urine samples reached a peak at 0–4 h, and then gradually decreased to a concentration of 0.001 μg/mL at 8–12 h, whereas the highest concentration of tangeretin in fecal samples was found at 12–24 h. The recovery of tangeretin excreted in urine and fecal samples during 0–48 h accounted for 0.0026 and 7.54% of the total dose, respectively. Previously, the metabolites of tangeretin in urine and feces have been elucidated in rats [24]. The rats were fed with 100 mg/kg tangeretin for 12 consecutive days and then placed in metabolic cages for 24-h in order to collect urine and fecal samples. No detectable tangeretin was found in urine samples, whereas only 7.07% of the daily dose was recovered in fecal samples. Consistent with those findings, our study also showed that only 7.54% of tangeretin was excreted through feces. Compared to their results, trace amounts of urinary tangeretin detected in our study may be due to the high sensitivity of mass spectrometry. With regards to research into urinary and fecal excretion of tangeretin, Nielsen et al. found 38% of tangeretin was excreted as glucuronic acid or sulfate conjugates and demethylated tangeretin were also identified by mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry [24]. Recently, an in vivo study reported that the major metabolites of PMFs in urine samples were demethylated flavones, glucuronide and sulfate conjugates, whereas only demethylated flavones were found in the feces [30]. Therefore, the recovery of unchanged tangeretin found in our study in the urine and fecal samples was less than 8%, indicating that approximately 92% of tangeretin was either absorbed or excreted in the form of metabolites, mainly demethylated tangeretin and conjugates of glucuronates and sulfates.

In conclusion, our pharmacokinetic study investigated the concentrations of tangeretin at different time intervals after either oral administration or intravenous injection. The calculated absolute oral bioavailability of tangeretin in rats was 27.11%. In tissue distribution, we further found that tangeretin was mainly concentrated in the kidney, lung and liver. In the gastrointestinal tract, a significant amount of tangeretin accumulated in the stomach, implying that tangeretin may be absorbed through stomach tissue. In addition, less than 8% of tangeretin was excreted in either urine or feces, indicating that approximately 92% of tangeretin was either absorbed or excreted in the form of its metabolites, probably demethylated tangeretin and conjugates of glucuronates and sulfates. Collectively, our current findings will provide a more complete understanding of the biological actions of tangeretin in vivo.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2017.08.003.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Pan MH, Lai CS, Wu JC, Ho CT. Molecular mechanisms for chemoprevention of colorectal cancer by natural dietary compounds. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:32–45. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim HP, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS. Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;96:229–45. doi: 10.1254/jphs.crj04003x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vauzour D, Vafeiadou K, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Rendeiro C, Spencer JP. The neuroprotective potential of flavonoids: a multiplicity of effects. Genes Nutr. 2008;3:115–26. doi: 10.1007/s12263-008-0091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li S, Pan MH, Lo C-Y, Tan D, Wang Y, Shahidi F, et al. Chemistry and health effects of polymethoxyflavones and hydroxylated polymethoxyflavones. J Funct Foods. 2009;1:2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li S, Wang H, Guo L, Zhao H, Ho CT. Chemistry and bioactivity of nobiletin and its metabolites. J Funct Foods. 2014;6:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lai CS, Wu JC, Ho CT, Pan MH. Disease chemopreventive effects and molecular mechanisms of hydroxylated polymethoxyflavones. Biofactors. 2015;41:301–13. doi: 10.1002/biof.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lou SN, Ho CT. Phenolic compounds and biological activities of small-size citrus: Kumquat and calamondin. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:162–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nogata Y, Sakamoto K, Shiratsuchi H, Ishii T, Yano M, Ohta H. Flavonoid composition of fruit tissues of citrus species. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 2006;70:178–92. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feng X, Zhang Q, Cong P, Zhu Z. Simultaneous determination of flavonoids in different citrus fruit juices and beverages by high-performance liquid chromatography and analysis of their chromatographic profiles by chemometrics. Anal Methods. 2012;4:3748–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Onda K, Horike N, Suzuki T, Hirano T. Polymethoxyflavonoids tangeretin and nobiletin increase glucose uptake in murine adipocytes. Phytother Res. 2013;27:312–6. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lakshmi A, Subramanian S. Chemotherapeutic effect of tangeretin, a polymethoxylated flavone studied in 7, 12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced mammary carcinoma in experimental rats. Biochimie. 2014;99:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen KH, Weng MS, Lin JK. Tangeretin suppresses IL-1beta-induced cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression through inhibition of p38 MAPK, JNK, and AKT activation in human lung carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sundaram R, Shanthi P, Sachdanandam P. Effect of tangeretin, a polymethoxylated flavone on glucose metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:793–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kawaii S, Tomono Y, Katase E, Ogawa K, Yano M. Antiproliferative activity of flavonoids on several cancer cell lines. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1999;63:896–9. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee YY, Lee EJ, Park JS, Jang SE, Kim DH, Kim HS. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanism of tangeretin in activated microglia. J Neuroimmune Pharm. 2016;11:294–305. doi: 10.1007/s11481-016-9657-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lei L, Li YM, Wang X, Liu Y, Ma KY, Wang L, et al. Plasma triacylglycerol-lowering activity of citrus polymethoxylated flavones is mediated by modulating the genes involved in lipid metabolism in hamsters. Eur J Lipid Sci Tech. 2016;118:147–56. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma LL, Wang DW, Yu XD, Zhou YL. Tangeretin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through upregulation of PTEN expression in glioma cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;81:491–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurowska EM, Manthey JA, Casaschi A, Theriault AG. Modulation of HepG2 cell net apolipoprotein B secretion by the citrus polymethoxyflavone, tangeretin. Lipids. 2004;39:143–51. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shu Z, Yang B, Zhao H, Xu B, Jiao W, Wang Q, et al. Tangeretin exerts anti-neuroinflammatory effects via NF-kappaB modulation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated microglial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kandaswami C, Perkins E, Soloniuk DS, Drzewiecki G, Middleton E., Jr Antiproliferative effects of citrus flavonoids on a human squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. Cancer Lett. 1991;56:147–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu Y-T, Ting Y, Hu JY, Hsieh SC. Techniques and methods to study functional characteristics of emulsion systems. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He X, Hwang HM. Nanotechnology in food science: functionality, applicability, and safety assessment. J Food Drug Anal. 2016;24:671–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manthey JA, Cesar TB, Jackson E, Mertens-Talcott S. Pharmacokinetic study of nobiletin and tangeretin in rat serum by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:145–51. doi: 10.1021/jf1033224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nielsen SE, Breinholt V, Cornett C, Dragsted LO. Biotransformation of the citrus flavone tangeretin in rats. Identification of metabolites with intact flavane nucleus. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38:739–46. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wei GJ, Hwang LS, Tsai CL. Absolute bioavailability, pharmacokinetics and excretion of 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethoxyflavone in rats. J Funct Foods. 2014;7:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Causon R. Validation of chromatographic methods in biomedical analysis. Viewpoint and discussion. J Chromatogr B. 1997;689:175–80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumar A, Devaraj VC, Giri KC, Giri S, Rajagopal S, Mullangi R. Development and validation of a highly sensitive LC-MS/MS-ESI method for the determination of nobiletin in rat plasma: application to a pharmacokinetic study. Biomed Chromatogr. 2012;26:1464–71. doi: 10.1002/bmc.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li T, Yan Z, Zhou C, Sun J, Jiang C, Yang X. Simultaneous quantification of paeoniflorin, nobiletin, tangeretin, liquiritigenin, isoliquiritigenin, liquiritin and formononetin from Si-Ni-San extract in rat plasma and tissues by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2013;27:1041–53. doi: 10.1002/bmc.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wen X, Walle T. Methylated flavonoids have greatly improved intestinal absorption and metabolic stability. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1786–92. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mekjaruskul C, Jay M, Sripanidkulchai B. Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, tissue distribution, excretion, and metabolite identification of methoxyflavones in Kaempferia parviflora extract in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:2342–53. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.047142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walle T, Ta N, Kawamori T, Wen X, Tsuji PA, Walle UK. Cancer chemopreventive properties of orally bioavailable flavonoids–methylated versus unmethylated flavones. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Datla KP, Christidou M, Widmer WW, Rooprai HK, Dexter DT. Tissue distribution and neuroprotective effects of citrus flavonoid tangeretin in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3871–5. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murakami A, Koshimizu K, Ohigashi H, Kuwahara S, Kuki W, Takahashi Y, et al. Characteristic rat tissue accumulation of nobiletin, a chemopreventive polymethoxyflavonoid, in comparison with luteolin. Biofactors. 2002;16:73–82. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520160303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bei D, An G. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of 5,7-dimethoxyflavone in mice following single dose oral administration. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;119:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wen X, Walle T. Methylation protects dietary flavonoids from rapid hepatic metabolism. Xenobiotica. 2006;36:387–97. doi: 10.1080/00498250600630636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nielsen SE, Breinholt V, Justesen U, Cornett C, Dragsted LO. In vitro biotransformation of flavonoids by rat liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 1998;28:389–401. doi: 10.1080/004982598239498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burapan S, Kim M, Han J. Demethylation of polymethoxyflavones by human gut bacterium, Blautia sp. MRG-PMF1. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:1620–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim M, Kim N, Han J. Metabolism of Kaempferia parviflora polymethoxyflavones by human intestinal bacterium Bautia sp. MRG-PMF1. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:12377–83. doi: 10.1021/jf504074n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]