Summary

The UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) was formed in 2002 with the aim of developing and supporting high‐quality independent national clinical trials that address prioritized research questions for people with skin disease. Its philosophy is to democratize UK dermatological clinical research and to tackle important clinical questions that industry has no incentive to answer. The network also plays a key role in training and capacity development. Its membership of over 1000 individuals includes dermatology consultants, trainees, dermatology nurses, general practitioners, methodologists and patients. Its organizational structures are lean and include a co‐ordinating team based at the Centre of Evidence‐Based Dermatology in Nottingham, and an executive with independent members to ensure probity and business progression. A prioritization panel and steering group enable a pipeline of projects to be prioritized and refined for external funding from independent sources. The UK DCTN has supported and completed 12 national clinical trials, attracting investment of over £15 million into UK clinical dermatology research. Trials have covered a range of interventions from drugs such as doxycycline (BLISTER), silk clothing for eczema (CLOTHES) and surgical interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa (THESEUS). Trial results are published in prestigious journals and have global impact. Genuine partnership with patients and carers has been a strong feature of the network since its inception. The UK DCTN is proud of its first 20 years of collaborative work, and aims to remain at the forefront of independent dermatological health technology assessment, as well as expanding into areas including diagnostics, artificial intelligence, efficient studies and innovative designs.

The UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) was formed in 2002 with the aim of developing and supporting high‐quality independent national clinical trials that address prioritized research questions for people with skin disease. The figure shows the UK DCTN infrastructure.

What is the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network?

The creation of an independent clinical trials network led by the dermatology community and patients began in around 2000, and the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) was formally announced following an exploratory meeting held at the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) headquarters in 2002. Four factors drove the need for such a network: (i) the need for trials addressing questions about commonly used treatments of uncertain benefit that industry has no incentive to tackle; (ii) the desire to democratize research, and to empower clinicians and nurses to identify important clinical uncertainties and to work collectively to address them; (iii) the need to ensure that patients' and carers' voices are heard on the prioritization and conduct of such trials; and (iv) the need to ensure high‐quality clinical trial standards that can influence policy and practice for the benefit of dermatology patients.

Since 2002, the UK DCTN has grown in membership to over 1000 members, including dermatology consultants and trainees, patients and carers, dermatology nurses, academics, methodologists, administrators, general practitioners, and anyone with an interest in skin disease.

What does the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network do?

The network's main business is to identify, prioritize and, develop feasible and needed clinical trial research questions into proposals that can be funded by independent sources such as the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) or charities. 1 Trial proposals from healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients emerge from the ‘coalface’ and include all forms of health technology assessment, including drugs and other technologies such as psychological interventions. Many network members also undertake Cochrane systematic reviews that identify research uncertainties. Priority setting partnerships between HCPs and patients for specific disease areas also feature prominently (Table 1). UK DCTN colleagues have also contributed significantly to developing core outcome sets for skin diseases such as vitiligo, eczema and hidradenitis suppurativa. 2 , 3 , 4 Although not initially intended primarily as a training and education network, capacity building has become an important function of the network and is described in Part 2 of this review. The network conducts surveys and produces regular newsletters. It directly funds feasibility studies with up to £10 000 for annual themed calls, often in partnership with charities and the BAD in order to increase chances of winning funds for definitive trials. The themed calls to date are summarized in Table 2. 5 , 6 , 7

Table 1.

Impacts arising from UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network Priority Setting Partnerships.

| Skin topic | Leads | UK DCTN role | Impact (subsequent studies) | Other impact | Top 10 uncertainties publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed PSPs (date) | |||||

| Vitiligo (2010) | Kim Thomas, Viktoria Eleftheriadou; CEBD UoN | Partner | HI‐LIGHT | https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdv.15168 | Eleftheriadou et al. (2011)38 |

| Eczema (2012) | Kim Thomas, Tessa Clarke; CEBD UoN | Coordinator | TREAT, TEST, ECO, BEEP, CLOTHES, BATHE, BEE | WAPs https://bjgp.org/content/68/667/e81 | Batchelor et al. (2012)39 |

| HS (2013) | John Ingram; University of Wales | Funder and Coordinator | THESEUS | Deroofing guide videos on YouTube® | Ingram et al. (2014)40 |

| Acne (2014) | Alison Layton, Anne Eady; Harrogate DGH | Co‐funder and partner | SAFA | Cochrane review on treatments for acne scars | Layton et al. (2015) 5 |

| Hair loss (2015) | Abby Macbeth, Norwich; Alopecia UK | Partner | Alopecia UK studies listed here | Two articles published: one on alopecia areata and other on hair loss | Macbeth et al. (2016, 2017)41,42 |

| Cellulitis (2017) | Kim Thomas, Jo Chalmers; CEBD UoN | Funder and Coordinator | COAT (provisional) | Outcomes in cellulitis trials | Thomas et al. (2017)43 |

| LSc (2018) | Rosalind Simpson; CEBD UoN | Coordinator | CORALs | Simpson et al. (2018)44 | |

| Psoriasis (2018) | Helen Young, Rabiya Majeed‐Ariss; UoM | Partner and support | What patients and clinicians believe is ‘unknown’ about psoriasis | YouTube® video about psoriasis treatments | Majeed‐Aris et al. (2019)45 |

| Hyperhidrosis (2019) | Louise Dunford; De Montfort University Leicester | Co‐funder and partner | Cochrane review underway | National research network setup | Dunford et al.46 |

| Ongoing PSPs | |||||

| Pemphigus and pemphigoid | Karen Harman, CEBD UoN | Coordinator | – | – | – |

| Skin cancer surgery | Aaron Wernham, David Veitch | Funder and partner | – | – | – |

CEBD, Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, Population and Lifespan Sciences; DGH, District General Hospital; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; LSc, lichen sclerosus; PSP, Priority Setting Partnership; UK DCTN, UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network; UoM, University of Manchester; UoN, University of Nottingham.

Table 2.

UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network themed calls.

| Year (theme) | Funded project [researchers] | Status |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 (acne) | Acne Priority Setting Partnership [Alison Layton, Harrogate] | Project completed 5 |

| 2013 (vitiligo) | Psychological Interventions for Vitiligo Feasibility Work [Alia Ahmed, London] | Project completed 6 |

| 2014 (dermatological surgery) | The HEALS study [Emma Pynn, Wales and Jane Nixon, Leeds] | Project completed and submitted for publication |

| 2015 (rare skin disease) | PATHS: Patient Reported Outcome Measures for HS [John Ingram, Cardiff] | Project withdrawn; superseded by the international HISTORIC initiative |

| 2016 (hair and nails) | ROMA: Patient Reported Outcome Measures for Alopecia Areata [Abby Macbeth, Norwich] | Project completed and in write‐up |

| 2017 (skin health for older people) | Feasibility Work to Support the SCC‐AFTER Study (an RCT investigating the use of Adjuvant Radiotherapy in High‐Risk SCC) [Catherine Harwood, London and Agata Rembeliak, Manchester] | Project completed 7 |

| 2018 (supporting recently completed PSPs) | Developing core outcomes for vulval lichen sclerosus (CORALS) [Rosalind Simpson, Nottingham] | Project ongoing |

| 2019 (dermatological surgery; co‐funded with the BSDS) | Dermatological Surgery for Skin Cancer Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) [Aaron Wernham, Midlands and David Veitch, Leicester] | Project ongoing |

| 2020 (psychological interventions for skin disorders, funded by a donation from the BAD) | Development of virtual habit reversal intervention material for children with atopic eczema [Susannah Baron, London and Ingrid Muller, Southampton] | Project ongoing |

| 2021 (paediatric dermatology; co‐funded with the NES and BSPAD |

Supporting children and young people's sLeep in those with EczEma Programme (SLEEP) Survey and Focus Groups [Conor Broderick and Carsten Flohr, London] Patient‐reported screening and assessment instruments for depression, self‐harm and suicidality in children/young people and establishing their clinical utility, acceptability, and feasibility for use in acne clinical trials and clinical practice [Damian Wood and Jane Ravenscroft, Nottingham] Feasibility work to support a randomized controlled trial on the equivalence and acceptability of teleconsultation for follow‐up of paediatric eczema compared with face‐to‐face consultation [Natalie King Stokes on behalf of UK DCTN Paediatric Dermatology Trainee Group, various] |

Projects in setup |

BAD, British Association of Dermatologists; BSDS, British Society for Dermatological Surgery; BSPAD, British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Dermatology; NES, National Eczema Society; UK DCTN, UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network.

How does the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network carry out its work?

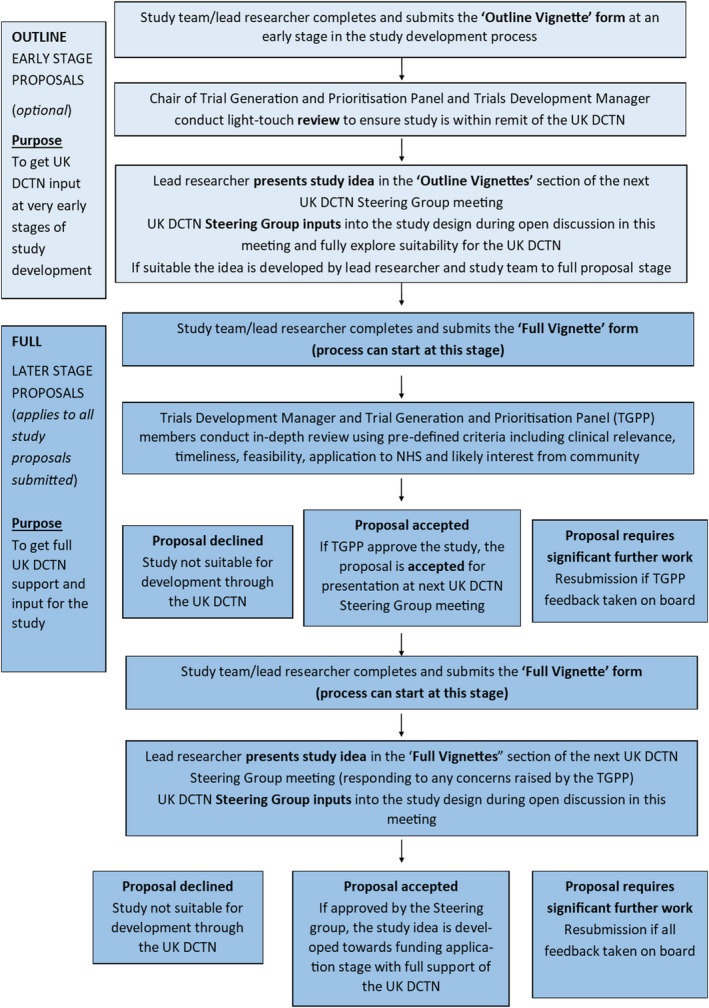

An effective network requires good structure and process that can respond to the changing needs of members and the National Health Service, and the funder's priorities. 8 The UK DCTN working groups are summarized in Fig. 1. Day‐to‐day management is undertaken by a part‐time Network Manager, Co‐Ordinator, Trial Development Manager and Network Chair at the Centre of Evidence‐Based Dermatology (CEBD). Strategic and financial decisions are undertaken by an Executive with an independent Chair and members. Decisions for trial progression are made by a Steering Group composed of elected members from all UK regions, patients, and methodologists such as statisticians, qualitative researchers and health economists. The flow of work from submission to approval (summarized in Fig. 2) ensures early input into the prioritization, feasibility, suitability, design and delivery of UK DCTN trials. Our process also reassures funders such as the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme that topic prioritization and study quality issues have been addressed before funding applications are made. 9 The network is an advocate of reducing research waste, 10 and ensures that all of its trials are registered prospectively and reported fully using CONSORT guidelines according to the ‘Place your bet and show us your hand’ principle. 11 Once funded, trials continue to be supported and disseminated by the network, working closely with the NIHR dermatology speciality group, which is a national network of principal investigators and research nurses funded by the NIHR to deliver approved national trials.

Figure 1.

UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) infrastructure. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2.

Flow of proposals submitted to the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN). TGPP, Trial Generation and Prioritization Panel. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Where do patients come into it all?

Working with patients and carers has been a feature of the UK DCTN since 2002, long before ‘patient and public involvement’ (PPI) became an expectation for UK health research. Patients are involved at every stage: making trial suggestions, commenting on trial proposals, voting in steering group meetings and also as independent members of the UK DCTN Executive. The CEBD patient panel (Fig. 3) deserves special mention. 12 It is composed of patients and carers of all ages, genders and ethnicities, who meet to provide detailed comments on network proposals from a patient perspective, facilitated by the network manager. Some patient partners have gone on to become co‐applicants in funded trials, while others are involved in developing core outcome sets and Cochrane reviews. 13

Figure 3.

Some patient partners such as Maxine Whitton MBE (pictured here) have been instrumental in driving research into neglected areas such as vitiligo by undertaking Cochrane reviews, developing core outcomes and eventually becoming co‐applicants on clinical trials such as HI‐LIGHT. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

What has the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network done so far?

Completed trials are summarized in Table 3. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 The first UK DCTN trial was on antibiotics to prevent cellulitis recurrences, and exemplifies the aims of the network. The idea came from a busy district hospital dermatologist (the late Dr Neil Cox 31 ) and evaluated a low‐cost intervention (generic penicillin V) that is of little interest to industry, assessing it for a serious disease that did not seem to belong to any specialism. 32 This pragmatic trial (the largest study of its kind) recruited 274 patients across the UK and was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. 14 It showed that low‐dose penicillin reduced the hazard of cellulitis recurrence by 45%. Other trials (Table 3) reflect the diverse nature of interventions tested, including water softeners for eczema 16 and a handheld ultraviolet device for vitiligo. 24 Some widely used interventions, such as silk clothing for eczema, 25 failed to show any benefit, allowing the NHS to cease investment in ineffective treatments. UK DCTN trials are also influential internationally, 33 with direct impacts such as adoption of the trial drug, or giving clinicians more confidence in using drugs in slightly different ways for the same condition. The educational value of good trial design for journal club discussions has also been highlighted. The UK DCTN has stimulated the formation of a Canadian dermatology trials network (C‐Nest; the clinical trials unit of SkIN Canada) and the International Federation Of Dermatology Trial Networks hosted by the UK DCTN. 34

Table 3.

Completed trials.

| Study | Description | Publications |

|---|---|---|

| PATCH I and PATCH II | Do prophylactic antibiotics (taken for 12 & 6 months) prevent further episodes of cellulitis of the leg? (Neil Cox, Carlisle) | The PATCH I 14 and PATCH II 15 trials showed that taking low‐dose penicillin after an episode of cellulitis reduced the number of repeat episodes |

| SWET (adopted) | Can ion‐exchange water softeners help reduce eczema severity in children? (Hywel Williams and Kim Thomas, Nottingham) | The SWET trial showed no objective difference in outcomes between the children whose homes were fitted with a water softener and those without 16 |

| SINS (adopted) | Comparison of excisional surgery with imiquimod cream for nodular and superficial basal cell carcinoma (Hywel Williams, Nottingham) | The SINS trial demonstrated that more patients had their BCC successfully treated by surgery than imiquimod. However, the results showed that imiquimod might still be a useful treatment for smaller, lower‐risk BCCs and for patients who would prefer not to have surgery (Year 3 study results, 17 Year 5 study results 18 ) |

| BLISTER | Is doxycycline a good alternative to prednisolone for treating bullous pemphigoid? (Fenella Wojnarowska, Oxford and Hywel Williams, Nottingham) | The BLISTER study showed that although not quite so effective in the short term, doxycycline is a significantly safer treatment in the long term 19 |

| STOP GAP | Comparing the use of prednisolone and ciclosporin for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum (Tony Ormerod, Aberdeen) | The STOP GAP trial found no difference between ciclosporin and prednisolone in the speed of healing and in the median time to healing. In both groups, <50% of ulcers had healed by 6 months (main study results, 20 topical study results 21 ) |

| LIMIT‐1 | Is imiquimod a sufficiently effective treatment for lentigo maligna? (Jerry Marsden, Birmingham) | The LIMIT‐1 study showed that imiquimod was not as effective as surgery for the clearance of lentigo maligna 2 |

| hELP | The effectiveness of tablet treatments for moderate or severe vulval erosive lichen planus (feasibility study) (Rosalind Simpson, Nottingham) | This study provided valuable evidence for future trials in the area (feasibility results 23 ) |

| HI‐LIGHT | Topical corticosteroid and home‐based narrowband UVB for active and limited vitiligo (Jonathan Batchelor and Kim Thomas, Nottingham) | The HI‐LIGHT study showed that using both treatments together was better than using steroid ointment on its own. It also found that the vitiligo tended to return once treatments were stopped 24 |

| CLOTHES | The role of specialist silk clothing in the management of paediatric eczema (Kim Thomas, Nottingham) | The silk garments in the CLOTHES trial did not appear to provide additional clinical or economic benefits over standard care for the management of children with eczema 25 |

| BEEP | Barrier enhancement for eczema prevention in newborn babies at increased risk of eczema (Hywel Williams, Nottingham) | The BEEP study showed that the use of emollients from birth does not prevent eczema from developing in babies with an increased risk of developing eczema (2‐year study results) 26 |

| APRICOT (adopted study) | Treatment of pustular psoriasis with IL‐1 receptor antagonist anakinra (Catherine Smith, London) | The APRICOT study demonstrated that anakinra is not an effective treatment for pustular psoriasis 27 |

| SPOT | Treatments for preventing squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant patients (feasibility study) (Catherine Harwood, London) | The SPOT study showed that trials of topical AK treatments in organ transplant patients for cSCC chemoprevention are feasible and AK activity results support further investigation in future Phase III trials 28 |

| TEST | What is the value of food allergy testing in infants with early onset eczema (pilot study)? (Matt Ridd, Bristol) | In write‐up; study protocol published 29 |

| BEE | Best emollient for eczema – a study comparing lotion, cream, gel and ointment in children with eczema (Matt Ridd, Bristol) | Submitted for publication; study protocol published 30 |

| TREAT | Comparing the use of methotrexate and ciclosporin for the treatment of severe eczema in children (Carsten Flohr, London) | In write‐up |

| OASIS | An observational study to investigate surgical site infection in ulcerated skin cancers (feasibility study) (Rachel Abbott, Cardiff) | Submitted for publication |

AK, actinic keratosis; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; IL‐2, interleukin‐2; cSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; UVB, ultraviolet B.

What is the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network doing now?

Ongoing funded trials 35 demonstrate a diverse range of topic areas, including common conditions such as acne and eczema, and less common conditions such as pustular psoriasis. The BEACON trial seeks to compare several systemic therapies in atopic eczema, and is the first adaptive platform study of its kind in dermatology, illustrating the cutting‐edge methodology 36 that the UK DCTN embraces working with accredited clinical trial units. The trials are summarized in Table 4. 5 The network also evaluates diagnostic tests, as exemplified by the TEST study 29 exploring the utility of food allergy testing in infants with early‐onset eczema. Despite the COVID‐19 pandemic, nearly all UK DCTN trials are recruiting to time and target, illustrating the determined collective efforts of the NIHR dermatology specialty group 37 and UK DCTN working alongside each other.

Table 4.

Ongoing trials.

| Study | Description | Further information |

|---|---|---|

| ALPHA | Comparison of alitretinoin and PUVA for the treatment of severe chronic hand eczema (Miriam Whitmann, Leeds) | https://ctru.leeds.ac.uk/alpha/ |

| SAFA | Spironolactone for the treatment of adult female acne (Miriam Santer, Southampton and Alison Layton, Harrogate) | https://www.southampton.ac.uk/safa/index.page |

| THESEUS | A study to inform the design of future HS trials and to understand how HS treatments are currently used (John Ingram, Cardiff) | https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/centre‐for‐trials‐research/research/studies‐and‐trials/view/theseus |

| BEACON | Best systemic treatments for adults with eczema over the long term (Catherine Smith and Andrew Pink, London) | https://www.beacontrial.org/ |

HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; PUVA, psoralen ultraviolet A.

Pipeline and future ambitions

There is a substantial pipeline of trial suggestions, which are at various stages of development according to the network's ‘traffic light’ system (Table 5). The network will continue to invest strategically in diverse areas of dermatology; for instance the UK DCTN themed calls are genital dermatoses for 2022 and skin of colour for 2023. The network strives to remain at the cutting edge of innovative trial design, and will expand into trials that include diagnostic tests and artificial intelligence, while retaining its ground‐roots appeal, democratic processes and original values.

Table 5.

Pipeline trials.

| Study | Stage of development | UK DCTN traffic light |

|---|---|---|

| Proactive v reactive therapy for the prevention of lichen sclerosus exacerbation and progression of disease (Rosalind Simpson and Kim Thomas, Nottingham) | Full application submitted to NIHR HTA (commissioned call) |

|

| Is a shorter course of oral flucloxacillin as effective as a longer course in initial treatment of lower limb cellulitis in primary care? (Nick Francis, Southampton) | Full application submitted to NIHR HTA (commissioned call) |

|

| Acne programme grant (Miriam Santer and Ingrid Muller, Southampton) | Full application submitted to NIHR Programme Grant scheme (investigator‐led) |

|

| RAPID eczema programme grant (Kim Thomas, Nottingham) | Full application submitted to NIHR Programme Grant scheme (commissioned call |

|

| TIGER: what is the value of food allergy testing in primary care in infants with early onset eczema? (Matthew Ridd, Bristol) | Full application submitted to NIHR HTA (investigator‐led) |

|

| Low‐dose isotretinoin for acne (Esther Burden‐Teh and Kim Thomas, Nottingham) | Outline application submitted to NIHR HTA (commissioned call) |

|

| HEALS: healing of excisional wounds on lower legs by secondary intention (Jane Nixon, Leeds, Aaron Wernham West Mids and David Veitch, Leicester) | Outline application submitted to NIHR HTA (investigator‐led) |

|

| SCC‐AFTER (ART for high‐risk SCC) (Agata Rembielak, Manchester; Catherine Harwood, London) | Outline application submitted to NIHR HTA (investigator‐led) |

|

| EXCISE: Is oral antibiotic treatment effective in preventing surgical site infection (SSI) after excision of an ulcerated skin cancer? And if so, is a single dose of antibiotic treatment no worse than a 7‐day course of antibiotic treatment in preventing SSI? (Rachel Abbott, Cardiff) | Planning outline application to NIHR HTA (investigator‐led) April 2022 |

|

| In low‐risk BCC, is clinic‐based diagnostic punch biopsy followed by observation, not inferior to standard pragmatic ablative treatment, in terms of skin cancer specific quality of life? (Jeremy Rodriguez and Rubeta Matin, Oxford) | Development ongoing |

|

| What is the effect of an adjunctive ‘Walk and Talk’ intervention for people with psoriasis on social connectedness? (Sharleen Hill and Sandy McBride, London) | Development ongoing |

|

| Can we manage keratoacanthoma better? Can we defer surgery to improve outcomes? (Saleem Tajbee and Dimitra Koch, Dorchester) | Development ongoing |

|

| COUN: Chemoprevention Of skin cancer Using Nicotinamide in Organ Transplant recipients (Rubeta Matin, Oxford) | Feasibility work complete but development of main study currently on hold |

|

| CANVAS: are superficial absorbable sutures non‐inferior to superficial non‐absorbable sutures? (Aaron Wernham, West Midlands; David Veitch, Leicester) | Feasibility work complete but development of main study currently on hold |

|

ART, adjuvant radiotherapy; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SSI, surgical site infection.

Conflict of interest

Hywel Williams is Chair of the UK DCTN, Carron Layfield is Network Manager of the UK DCTN and Margaret McPhee is the UK DCTN research co‐ordinator. None of the authors have any other conflicts of interest to declare.

CPD questions

Learning objective

To be better informed about the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) and the results of some of the studies undertaken through the UK DCTN.

Question 1

Which of the following statements about the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) is correct?

-

(a)

Membership is restricted to dermatologists.

-

(b)

The network only investigates drug interventions.

-

(c)

The network prioritizes trial suggestions.

-

(d)

All trial suggestions progress to full trials.

-

(e)

Patient involvement means patients participating in our trials.

Question 2

Which of the following was a finding of the PATCH 1 study?

-

(a)

Doxycycline can prevent cellulitis recurrence.

-

(b)

Compression is a useful treatment for cellulitis of the leg.

-

(c)

Penicillin is an effective treatment for acute cellulitis.

-

(d)

Penicillin V reduced the hazard of cellulitis recurrence in people with recurrent cellulitis of the leg.

-

(e)

Adverse events were very different in the penicillin and placebo groups.

Question 3

Which of the following statements about the SWET study is false?

-

(a)

The study was stimulated by epidemiological studies that found an increased risk of eczema in hard water areas.

-

(b)

The study was observer‐blinded.

-

(c)

The study evaluated the potential benefit of an ion‐exchange water softener for people with eczema.

-

(d)

The study did not find any additional benefit from water softeners when compared with usual care in this study population.

-

(e)

The results mean that softening water does not prevent eczema from starting in early life.

Question 4

Which of the following statements about the BLISTER study is false?

-

(a)

The study was stimulated by a Cochrane review of interventions for pemphigoid that suggested a possible benefit of tetracyclines.

-

(b)

The study evaluated a comparison of doxycycline vs. oral corticosteroids.

-

(c)

The study found that a strategy of starting off treatment with doxycycline 200 mg daily was noninferior to oral prednisolone at a dose of 0.5 mg/day, but it had fewer serious adverse effects than prednisolone.

-

(d)

The study suggests that starting off with oral doxycycline may be a useful strategy for people with extensive pemphigoid, resorting to oral corticosteroids if blister control is inadequate.

-

(e)

The results mean that oral treatment is preferred to topical corticosteroid treatment for pemphigoid.

Question 5

Which of the following statements about the HI‐LIGHT study for localized vitiligo is false?

-

(a)

The study included comparisons of (i) topical corticosteroid cream, (ii) a handheld ultraviolet (UV)B device and (iii) a dummy handheld UVB device.

-

(b)

The study compared the following three groups: (i) topical corticosteroids, (ii) a handheld UVB device and (iii) a combination of topical corticosteroids with a handheld UVB device.

-

(c)

The study showed that combination treatment with UVB and topical corticosteroids was better than topical corticosteroids alone.

-

(d)

Target patch treatment success for topical corticosteroids alone was 17%.

-

(e)

A combination of topical corticosteroids plus handheld UVB is now a first‐line treatment for generalized vitiligo.

Instructions for answering questions

This learning activity is freely available online at http://www.wileyhealthlearning.com/ced

Users are encouraged to

Read the article in print or online, paying particular attention to the learning points and any author conflict of interest disclosures.

Reflect on the article.

Register or login online at http://www.wileyhealthlearning.com/ced and answer the CPD questions.

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

Once the test is passed, you will receive a certificate and the learning activity can be added to your RCP CPD diary as a self‐certified entry.

This activity will be available for CPD credit for 2 years following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional period.

Supporting information

Supplementary Data S1 References for Table 1.

Acknowledgement

The UK DCTN thanks the BAD for its sustained support over the last 20 years and all of the UK DCTN individual members including patients and those who serve on its committees (see Appendix) who give their time freely to support the network. The UK DCTN is a registered UK charity (number 1115745) and is subject to Charity Commission rules. The network infrastructure is funded by the BAD and the University of Nottingham, with contribution in kind and donations from its members. The network also receives some funding for continuing support and dissemination from successful applications. The network does not accept funding from the pharmaceutical industry or other for‐profit organizations.

Learning points.

The UK DCTN is a democratic network that strives to support high‐quality clinical trials in dermatology.

Patients are and always have been at the heart of the network.

Clinical trial suggestions come from the network membership.

Trial prioritization follows a process starting with an outline vignette that is heard by a steering group.

The network directly supports the development of prioritized trial suggestions by means of surveys, expert critique and by directly funding feasibility studies.

The output of UK DCTN has shown what is possible by working collaboratively across professional boundaries.

Current UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UK DCTN) Committee Members

Executive

Stephen Jones (Independent Chair), Hywel Williams (UK DCTN Chair), Carron Layfield (UK DCTN Manager, Treasurer), Rubeta Matin, Nick Levell, Fiona Cowdell, Tim Burton (Patient Representative), Louisa May Adams (Patient Representative), Jez Frankel (Patient Representative) and Kim Thomas (Advisor).

Steering

Executive members plus Gayathri Perera, Mary Sommerlad, Carolyn Charman (deputy Yusur Al‐Niami), Sarah Worboys, Helen Young, Sharon Belmo, Tracey Sach, Lucy Bradshaw, Rachel Abbott, Abby Macbeth, Debbie Shipley, Areti Makrygeorgou, Tess McPherson, Claudia DeGiovanni, Evelyn Davies/Rhiannon Llewellyn (joint role), Melanie Westmoreland, Temporary Steering Committee members (UK DCTN Fellows); Anjali Pathak, Hannah Wainman, Christina MacNeil, Richard Barlow, Marianne de Brito, John Frewen, Anna Lalonde, Simi Sudhakaran, Eleanor Earp, Lloyd Steele, Andy Hodder and Alison Lowe.

Trial Generation and Prioritization Panel

Rubeta Matin (Chair)*, Alison Layton, Antonia Lloyd‐Lavery, Shernaz Walton, Alison Sears, Esther Burden‐Teh, Alana Durack, Aaron Wernham, Lucy Bradshaw, Jason Thomson, Nadine Marrouche, Alia Ahmed, Rosalind Simpson and Alison Lowe. (*From July 2022 the Trial Generation and Prioritization Panel Chair will be Rachel Abbott.)

Contributor Information

Hywel C. Williams, Email: hywel.williams@nottingham.ac.uk.

the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network:

Stephen Jones, Carron Layfield, Rubeta Matin, Nick Levell, Fiona Cowdell, Tim Burton, Louisa May Adams, Jez Frankel, Kim Thomas, Gayathri Perera, Mary Sommerlad, Carolyn Charman, Sarah Worboys, Helen Young, Sharon Belmo, Tracey Sach, Lucy Bradshaw, Rachel Abbott, Abby Macbeth, Debbie Shipley, Areti Makrygeorgou, Tess McPherson, Claudia DeGiovanni, Evelyn Davies, Rhiannon Llewellyn, Melanie Westmoreland, Anjali Pathak, Hannah Wainman, Christina MacNeil, Richard Barlow, Marianne de Brito, John Frewen, Anna Lalonde, Simi Sudhakaran, Eleanor Earp, Lloyd Steele, Andy Hodder, Alison Lowe, Alison Layton, Antonia Lloyd‐Lavery, Shernaz Walton, Alison Sears, Esther Burden‐Teh, Alana Durack, Aaron Wernham, Jason Thomson, Nadine Marrouche, Alia Ahmed, and Rosalind Simpson

References

- 1. Layfield C, Clarke T, Thomas K, Williams HC. Developing a network in a neglected area of clinical research the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network. Clin Invest 2011; 1: 943–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eleftheriadou V, Hamzavi I, Pandy AG et al. International Initiative for Outcomes (INFO) for vitiligo: workshops with patients with vitiligo on repigmentation. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 574–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas KS, Apfelbacher CA, Chalmers JR et al. Recommended core outcome instruments for health‐related quality of life, long‐term control and itch intensity in atopic eczema trials: results of the HOME VII consensus meeting. Br J Dermatol 2021; 185: 139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prinsen CAC, Spuls PI, Kottner J et al. Navigating the landscape of core outcome set development in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81: 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Layton A, Eady EA, Peat M et al. Identifying acne treatment uncertainties via a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed A, Steed L, Burden‐Teh E et al. Identifying key components for a psychological intervention for people with vitiligo – a quantitative and qualitative study in the United Kingdom using web‐based questionnaires of people with vitiligo and healthcare professionals. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 2275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thomson J, Matin R, Proby C et al. Management of high‐risk primary cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the head and neck region AFTER surgery (SCC‐AFTER): results of a feasibility survey of cancer multidisciplinary teams. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181 (Suppl): 106. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Layfield C, Yong A, Thomas KS, Williams HC. The UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network – how far have we come? Clin Invest 2014; 4: 209–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams HC. The NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme: research needed by the NHS. Available at: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/nihr‐health‐technology‐assessment‐programme‐nhs/85065 (accessed 19 January 2022).

- 10. Williams HC. Avoidable research waste in dermatology: what is the problem? Br J Dermatol 2022; 186: 383–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams HC, Gilchrest B. Clinical trials: place your bet and show us your hand. J Investig Dermatol 2015; 135: 325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmed A, Layfield C, Patient partnership in an academic research unit. Available at: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/07/05/amina‐ahmed‐and‐carron‐layfield‐patient‐partnership‐in‐an‐academic‐research‐unit (accessed 17 January 2022).

- 13. Whitton M, Pinart M, Batchelor JM et al. Evidence‐based management of vitiligo: summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174: 962–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams HC, Crook AM, Mason JM, UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Networks PATCH I Trial Team . Penicillin to prevent recurrent leg cellulitis. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Networks PATCH Trial Team , Thomas K, Crook C et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of cellulitis (erysipelas) of the leg – results of the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Networks PATCH II trial. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomas KS, Dean T, O'Leary C et al. A randomised controlled trial of ion‐exchange water softeners for the treatment of eczema in children. PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bath‐Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong S et al. Surgical excision versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal‐cell carcinoma (SINS): a multicentre, non‐inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams HC, Ozolins Bath‐Hextall F, M et al. Surgery versus 5% imiquimod for nodular and superficial basal cell carcinoma: 5‐year results of the SINS randomized controlled trial. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 614–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams HC, Wojnarowska F, Kirtschig G et al. Doxycycline versus prednisolone as an initial treatment strategy for bullous pemphigoid: a pragmatic, non‐inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 1630–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ormerod AD, Thomas KS, Craig FE et al. Comparison of the two most commonly used treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: results of the STOP GAP randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015; 350: h2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas KS, Ormerod AD, Craig FE et al. Clinical outcomes and response of patients applying topical therapy for pyoderma gangrenosum: a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 940–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marsden JR, Fox R, Boota NM et al. Effect of topical imiquimod as primary treatment for lentigo maligna: the LIMIT‐1 study. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 1148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simpson RC, Murphy R, Bratton DJ et al. Help for future research: lessons learned in trial design, recruitment, and delivery from the “hELP” study. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2018; 22: 405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas KS, Batchelor JM, Akram P et al. Randomised controlled trial of topical corticosteroid and home‐based narrowband UVB for active and limited vitiligo – results of the HI‐Light Vitiligo trial. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 828–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomas KS, Bradshaw LE, Sach TH et al. Silk garments plus standard care compared with standard care for treating eczema in children: a randomised, controlled, observer‐blind, pragmatic trial (CLOTHES Trial). PLoS Med 2017; 14: e1002280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chalmers JR, Haines R, Bradshaw LE et al. Daily emollient during infancy for prevention of eczema: the BEEP randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020; 395: 962–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cro S, Cornelius VR, Pink AE et al; APRICOT Study Group . Ankira for palmoplantar pustulosis: results from a randomized, double‐blind, two‐staged adaptive, placebo controlled trial (APRICOT). Br J Dermatol 2021. 10.1111/bjd.20653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hasan ZU, Ahmed I, Matin RN et al. Topical treatment of actinic keratoses in organ transplant recipients: a feasibility study for SPOT (Squamous cell carcinoma Prevention in Organ transplant recipients using Topical treatments). Br J Dermatol 2022. 10.1111/bjd.20974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ridd MJ, Edwards L, Santer M et al. TEST (Trial of Eczema allergy Screening Tests): protocol for feasibility randomised controlled trial of allergy tests in children with eczema, including economic scoping and nested qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e028428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ridd MJ, Wells S, Edwards L et al. Best emollients for eczema (BEE) – comparing four types of emollients in children with eczema: protocol for randomised trial and nested qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e033387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burns T. Neil Harrison Cox. Available at https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get‐file.ashx?id=414&itemtype=document (accessed 17 January 2022).

- 32. Thomas KS, UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network's PATCH study group . Studying a disease with no home – lessons in trial recruitment from the PATCH II study. Trials 2010; 11: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams HC, Rogers NK, Chalmers JR, Thomas KS. Scoping the international impact from four independent national dermatology trials. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021; 46: 657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. International Federation of Dermatology Clinical Trials . About the Federation. Available at: http://www.ifdctn.org/about‐the‐federation/about.aspx (accessed 19 January 2022).

- 35. UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network . Our trials. Ongoing studies. Available at: http://www.ukdctn.org/ourclinicaltrials/index.aspx (accessed 19 January 2022).

- 36. Saville BR, Berry SM. Efficiencies of platform clinical trials: a vision of the future. Clin Trials 2016; 13: 358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Institute for Health Research . Dermatology. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/explore‐nihr/specialties/dermatology.htm (accessed 28 December 2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data S1 References for Table 1.