Abstract

Dupilumab associated head and neck dermatitis is incompletely understood. This prospective multicentre prospective study identified baseline Malassezia‐specific IgE as associated with the development of Dupilumab associated head and neck dermatitis.

dear editor, Dupilumab‐associated head and neck dermatitis (DAHND) refers to the de novo development or exacerbation of head and neck dermatitis (HND) in the setting of dupilumab therapy. 1 , 2 It has been observed in 10% of atopic patients, 3 , 4 with the causative mechanisms incompletely understood. Proposed hypotheses have included site‐specific treatment failure of dupilumab as well as localized inflammatory reaction to facial Malassezia species. 5 , 6 , 7

This prospective cohort study aimed to assess whether baseline (pretreatment) Malassezia‐specific IgE levels were associated with the development of DAHND in individuals commencing dupilumab therapy for moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis. Over a 6‐month period from 1 March 2021 to 1 September 2021, 171 consecutive patients were included.

Age, sex, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, total serum IgE and Malassezia‐specific serum IgE as measured by ImmunoCAP solid phase sandwich immunoassay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were recorded. DAHND was defined as de novo or worsening (defined as a 50% worsening in head and neck EASI score) 5 HND after dupilumab commencement.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 8.4.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Univariate analysis was undertaken to examine the relationships between DAHND and a priori variables including age, sex, baseline EASI, baseline head and neck EASI subscore, baseline total IgE, baseline Malassezia‐specific IgE, and ratios of Malassezia‐IgE to total IgE. Gaussian distribution was not assumed, and nonparametric tests were utilized. Chi‐squared tests were used for binary variables (sex), and Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests for continuous variables. Significance was defined at P < 0·05, and adjustment for multiple comparisons made using Bonferroni correction. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between DAHND and baseline Malassezia‐specific IgE. A second logistic regression model was developed assessing the relationship between DAHND and baseline Malassezia‐specific IgE and the a priori identified covariates. Receiver operating curves (ROCs) were produced for total serum IgE, total serum Malassezia‐specific IgE and Malassezia IgE: total IgE ratio; and sensitivity and specificity were calculated.

Of the 171 consecutive participants included, 25 (14·7%) were diagnosed with DAHND. All patients with DAHND demonstrated EASI 75 (75% reduction from baseline in EASI response). Comparing individuals with DAHND and without DAHND, no statistically significant differences were identified between sex (P = 0·31), age (median 31 years vs. 35 years; P = 0·23), baseline EASI score (35·7 vs. 36·1; P = 0·88) or severity of baseline head and neck dermatitis (EASI 0·1 vs. 0·2; P = 0·95).

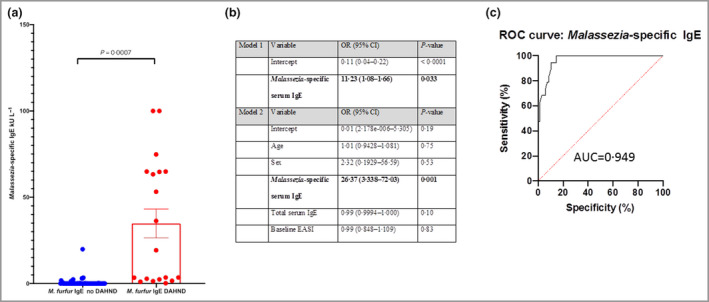

There was a statistically significant difference in serum Malassezia‐specific IgE between DAHND and non‐DAHND groups (median 31·95 kU L–1 vs. 2·27 kU L–1; P = 0·005) (Figure 1a). No statistically significant difference was seen in baseline serum total IgE levels (4570 kU L–1 vs. 4478 kU L–1; P = 0·95). Unadjusted logistic regression analysis (Figure 1b) identified increased odds of DAHND with every 1 kU mL–1 increase in baseline serum Malassezia‐specific IgE [odds ratio (OR) 11·23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3·68–63·73]. When adjusted for covariates (Figure 1b), there were greater odds of DAHND with every 1 kU mL–1 increase in baseline serum Malassezia‐specific IgE (OR 26·37, 95% CI 4·98–952·7). No examined covariates (age, sex, baseline EASI and total serum IgE) were statistically significant in altering the odds of DAHND.

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of levels of Malassezia‐specific serum IgE, stratified by the presence of dupilumab‐associated head and neck dermatitis (DAHND) or no DAHND. (b)

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with DAHND not including (model 1) and including (model 2) a priori covariates. (c) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC) analysis of Malassezia‐specific serum IgE. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index. Variables and their P‐values shown in bold were considered statistically significant (P < 0·05). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

ROC demonstrated a greater area under the curve (AUC) when examining the logistic regression model (AUC = 0·984) and Malassezia‐specific serum IgE model (AUC = 0·949) (Figure 1c) compared with total IgE (AUC = 0·643). Using the previously reported cut‐off for determination of a positive result for Malassezia‐specific IgE (0·35 kU mL–1), a positive baseline serum Malassezia‐specific IgE demonstrated a 94·1% sensitivity and 87·9% specificity for diagnosis of DAHND.

All participants experiencing DAHND were treated at the physician’s discretion, as no treatment standard for DAHND exists. Two of the 25 (8%) had topical mild‐to‐moderate corticosteroid or topical calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy prescribed, with a 100% (two of two) response rate. Thirteen of the 25 (52%) had combination corticosteroid/antifungal therapy (ketoconazole or clotrimazole) prescribed, with an 85% (11 of 13) response rate. Ten of 25 (40%) received itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for up to 28 days, with a 70% (seven of 10) response rate. Twenty of 25 (80%) experienced DAHND recurrence after cessation of therapy, and three of 25 (12%) discontinued dupilumab due to DAHND after failed itraconazole therapy.

The prospective nature of this study brings credence to the concept that Malassezia‐specific serum IgE may represent a potential safety biomarker in the setting of treatment of atopic dermatitis with dupilumab. This is supported by the high level of sensitivity and specificity identified in ROC analysis. Unfortunately, improvement in DAHND with therapy was often transient. This study is limited by short‐term follow‐up (28 weeks).

The potential mechanisms of DAHND can be postulated to involve prior Malassezia‐specific IgE sensitization, based on the results of this study and the observation of other authors. 3 , 7 The mechanism of action of dupilumab suggests that the mechanism of DAHND is likely to be independent of the Th2‐mediated pathways suppressed by dupilumab therapy. 8 In conclusion, baseline Malassezia‐specific IgE may be used as a biomarker to predict DAHND prior to dupilumab therapy.

Author contributions

Emily Kozera: Formal analysis (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Thomas Stewart: Data curation (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Kyra Gill: Formal analysis (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Mae Anne De La Vega: Data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). John W Frew: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (lead); supervision (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

Funding sources: this project was funded by an educational grant from LEO Pharma, who had no role in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the report or decision to submit the report for publication.

Conflicts of interest: J.W.F. has conducted advisory work for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, ChemoCentryx, AbbVie and UCB; has participated in trials for Pfizer, UCB, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and CSL; and received research support from Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, UCB and LEO Pharma. The remaining authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability: the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. de Beer FSA, Bakker DS, Haeck I et al. Dupilumab facial redness: positive effect of itraconazole. JAAD Case Rep 2019; 5:888–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soria A, Du‐Thanh A, Seneschal J et al. Development or exacerbation of head and neck dermatitis in patients treated for atopic dermatitis with dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol 2019; 155:1312–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan B, Grant‐Kels JM. Characterizing dupilumab facial redness: a multi‐institution retrospective medical record review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82:230–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muzumdar S, Zubkov M, Waldman R et al. Characterizing dupilumab facial redness in children and adolescents: a single‐institution retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:1520–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darabi K, Hostetler SG, Bechtel MA, Zirwas M. The role of Malassezia in atopic dermatitis affecting the head and neck of adults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:125–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jo CE, Finstad A, Georgakopoulos JR et al. Facial and neck erythema associated with dupilumab treatment: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84:1339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Wijs LEM, Nguyen NT, Kunkeler ACM et al. Clinical and histopathological characterization of paradoxical head and neck erythema in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:745–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harb H, Chatila TA. Mechanisms of dupilumab. Clin Exp Allergy 2020; 50:5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]