Abstract

Streptococcus suis is an important pathogen of swine which occasionally infects humans as well. There are 35 serotypes known for this organism, and it would be desirable to develop rapid methods methods to identify and differentiate the strains of this species. To that effect, partial chaperonin 60 gene sequences were determined for the 35 serotype reference strains of S. suis. Analysis of a pairwise distance matrix showed that the distances ranged from 0 to 0.275 when values were calculated by the maximum-likelihood method. For five of the strains the distances from serotype 1 were greater than 0.1, and for two of these strains the distances were were more than 0.25, suggesting that they belong to a different species. Most of the nucleotide differences were silent; alignment of protein sequences showed that there were only 11 distinct sequences for the 35 strains under study. The chaperonin 60 gene phylogenetic tree was similar to the previously published tree based on 16S rRNA sequences, and it was also observed that strains with identical chaperonin 60 gene sequences tended to have identical 16S rRNA sequences. The chaperonin 60 gene sequences provided a higher level of discrimination between serotypes than the 16S RNA sequences provided and could form the basis for a diagnostic protocol.

Streptococcus suis infections have been considered a major worldwide problem in the swine industry, particularly during the past 10 years. The natural habitat of S. suis is the upper respiratory tract, particularly the tonsils and nasal cavities, and the genital and alimentary tracts of pigs (20). This bacterium has been increasingly isolated from a wide range of mammalian species (including humans) and from birds, which suggests new concepts about some epidemiological aspects of the infection (13). In pigs, the most important clinical feature associated with S. suis is meningitis. However, other pathologies have also been described, such as arthritis, endocarditis, pneumonia, and septicemia with sudden death (20). It is also an important human pathogen, causing meningitis, endocarditis, and septicemia. The pathogenesis of the infection is not clear. Moreover, studies on this subject have been limited to serotype 2 and have concerned only the development of meningitis. Bacteria probably get into the blood from the tonsils, travel to the cerebrospinal fluid, and stimulate cytokine production that leads to an inflammatory infiltrate from the blood in the central nervous system (3). The increase in cell infiltration in the cerebrospinal fluid blocks sites of fluid efflux, increases intracranial pressure, and produces the neural damage typical of clinical signs of meningitis.

To date, 35 serotypes of S. suis have been described, and they are designated 1 through 34 and 1/2 (14, 15, 21, 25). There are wide variations in virulence between serotypes, as well as within each serotype. S. suis serotype 2 has been considered the most virulent serotype and the serotype most frequently isolated from diseased animals (13). Identification of S. suis isolates is possible with biochemical tests, especially when the isolates are recovered from diseased pigs and when serotyping is available. In recent years, an alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus that produces amylase but not acetoin has been considered S. suis (6). Serotyping based on capsular type is an important step in the diagnostic procedure. Serotype-specific isolation from contaminated tissues such as tonsils may also be carried out by an immunocapture method (16). Type-specific probes based on S. suis genes coding for the capsule and PCR assays based on capsular genes have been developed for serotypes 1, 2, and 9 (29). Genetic diversity of S. suis isolates between and within serotypes has been shown. The average level of pairwise DNA sequence identity among 13 S. suis strains belonging to a limited range of serotypes was more than 80%, confirming the relationship of these organisms at the species level. Nevertheless, another study, in which multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (18) was used to evaluate the diversity of a collection of mainly Australian isolates of S. suis divided into 14 serotypes, indicated that the species was genetically more diverse than anticipated on the basis of previous DNA-DNA hybridization studies (19, 22). The existence of genomic heterogeneity in S. suis isolates between and within serotypes has also been detected by restriction endonuclease analysis and ribotyping (1, 13, 28, 30). S. suis serotypes 20, 22, 26, 32, 33, and 34 are distantly related to the main group of S. suis on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequences but exhibit physiological characteristics and biochemical profiles comparable to those of other S. suis serotypes (4). Species-specific probes based on signature positions within the 16S rRNA gene sequences allow rapid and specific identification of most S. suis serotypes (2); the exceptions are the most divergent serotypes, serotypes 32, 33, and 34.

In previous study (4), Chatellier et al. attempted to identify the S. suis serotypes by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. This approach provided information on the phylogenetic relationships of serotype strains to each other but did not provide unambiguous identification since several serotypes had identical 16S rRNA sequences. Molecular methods based on protein-encoding genes may be more discriminating for closely related organisms, since the divergence of protein-encoding nucleotide sequences is less than that of genes coding for structural RNA, such as 16S rRNA. The ubiquitous and highly conserved 60-kDa chaperonins (variously known as Cpn60, HSP60, or GroEL) have been used previously (17) for taxonomic and molecular evolution studies. A method based on partial sequencing of the chaperonin 60 gene has been shown to distinguish between closely related species and subspecies in the genera Enterococcus (10), Streptococcus (9), and Staphylococcus (11, 12, 23).

The objective of the present study was to compare two molecular methods, one based on 16S rRNA and one based on the chaperonin 60 gene, for S. suis serotype identification. Our longer-term objective is to ascertain the suitability of chaperonin 60 gene sequences for development of a rapid S. suis identification system in which chaperonin 60 gene microarrays are used.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

The reference strains of S. suis serotypes 1 to 34 and 1/2 and other organisms relevant to this study, together with the GenBank accession numbers for their chaperonin 60 gene sequences, are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

S. suis isolates and other Streptococcus species investigated in this study

| Organism | Serotype | Source of isolation | Origin or Source | Accession no. for chaperonin 60 gene | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. suis strains | |||||

| 5428 | 1 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237423 | 25 |

| 2651 | 1/2 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237442 | 25 |

| 735 | 2 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237424 | 25 |

| 4961 | 3 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237425 | 25 |

| 6407 | 4 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237426 | 25 |

| 11538 | 5 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237427 | 25 |

| 2524 | 6 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237428 | 25 |

| 8074 | 7 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237429 | 25 |

| 14636 | 8 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237430 | 25 |

| 22083 | 9 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237431 | 14 |

| 4417 | 10 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237432 | 14 |

| 12814 | 11 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237433 | 14 |

| 8830 | 12 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237434 | 14 |

| 10581 | 13 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237435 | 14 |

| 13730 | 14 | Diseased human | The Netherlands | AF237436 | 14 |

| NCTC1046 | 15 | Diseased pig | The Netherlands | AF237437 | 14 |

| 2726 | 16 | Diseased pig | Denmark | AF237438 | 14 |

| 93A | 17 | Clinically healthy pig | Canada | AF237439 | 14 |

| NT77 | 18 | Clinically healthy pig | Canada | AF237440 | 14 |

| 42A | 19 | Clinically healthy pig | Canada | AF237441 | 14 |

| 86-5192 | 20 | Diseased calf | United States | AF237443 | 14 |

| 14A | 21 | Clinically healthy pig | Canada | AF237444 | 14 |

| 88-1861 | 22 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237445 | 14 |

| 89-2479 | 23 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237446 | 15 |

| 88-5299A | 24 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237447 | 15 |

| 89-3576-3 | 25 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237448 | 15 |

| 89-4109-1 | 26 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237449 | 15 |

| 89-5259 | 27 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237450 | 15 |

| 89-590 | 28 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237451 | 15 |

| 92-1191 | 29 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237452 | 21 |

| 92-1400 | 30 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237453 | 21 |

| 92-4172 | 31 | Diseased calf | Canada | AF237454 | 21 |

| EA1172.91 | 32 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237455 | 21 |

| EA1832.92 | 33 | Diseased lamb | Canada | AF237456 | 21 |

| 92-2742 | 34 | Diseased pig | Canada | AF237457 | 21 |

| Other Streptococcus species | |||||

| S. agalactiae | ATCC 12386 | AF352811 | Goh et al.a | ||

| S. anginosus | ATCC 33397 | AF352808 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. bovis | ATCC 33317 | AF352798 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. bovis | ATCC 9809 | AF237460 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. canis | ATCC 43496 | AF352804 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. cristatus | ATCC 51100 | AF352802 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. iniae | ATCC 29178 | AF064076 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. mitis | ATCC 49456 | AF352801 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. mutans | ATCC 25175 | AF352809 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. oralis | ATCC 35037 | AF237462 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. parasanguinis | ATCC 15912 | AF352799 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. pneumoniae | ATCC 27336 | AF237459 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. pneumoniae | ATCC 33400 | AF352805 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. porcinus | ATCC 43138 | AF352810 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. pyogenes | ATCC 12344 | AF352806 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. pyogenes | ATCC 19615 | AF237461 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. salivarius | ATCC 7073 | AF352807 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. thermophilus | ATCC 19258 | AF352800 | Goh et al. | ||

| S. vestibularis subsp. denitrificans | ATCC 49124 | AF352803 | Goh et al. |

S. H. Goh, J. Hill, and S. Hemmingsen, unpublished data.

DNA preparation.

Each strain was subcultured on 5% (vol/vol) blood agar plates at 37°C for 18 h. Genomic DNA was extracted by the guanidium thiocyanate method (26).

Amplification of chaperonin 60 genes.

Template DNAs for sequencing were prepared by PCR amplification of genomic DNA using primers H729, (5′-CGC CAG GGT TTT CCC AGT CAC GAC GAI III GCI GGI GAY GGI ACI ACI AC-3′) and H730 (5′-AGC GGA TAA CAA TTT CAC ACA GGA YKI YKI TCI CCR AAI CCI GGI GCY TT); inosine was used to reduce the degeneracy of the sequences (24). These primers were derived from the previously described H279A and H280A primers (12) by addition of the sequences for commercially available M13 24-bp sequencing primers (underlined nucleotides). They were designed to amplify the region between codons 92 and 277 based on the Escherichia coli groEL sequence (accession number X07850).

The standard PCR conditions were as follows: each 100-μl reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, 1 ng of genomic DNA, 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.5 μg of each primer. The following thermal cycle was used: denaturation for 3 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 37°C, and 5 min at 72°C and then one cycle of 10 min at 72°C. The PCR products were purified on QIAquick spin columns (catalog number 28104; Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.).

DNA sequence determination.

Sequencing primers M13 forward and reverse, incorporated into amplification primers H729 and H730, were used for sequence determination with a Perkin-Elmer ABI 377 automated sequencer. Two internal primers, cpn60F2 (5′-GTA TGG ARA CWG ARY TKG ATG T-3′; corresponding to bases 1015 to 1036 of the E. coli DNA sequence) and cpn60R2 (5′-ATT ITC AAG ITC IGC IAC CAT; corresponding to bases 1121 to 1101 of the E. coli sequence), were used for shorter runs with a Perkin-Elmer 373 automated sequencer.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Multiple DNA and protein alignments were obtained by using CLUSTALW software (31). Phylogeny calculations, including distance calculations and generation of phylogenetic trees, were performed by using the PHYLIP package (7, 8). Unrooted trees were calculated by the neighbor-joining method (27), as implemented in the neighbor module of PHYLIP. DNA distances were calculated with dnadist, using the maximum-likelihood option. Protein distances were calculated with protdist, using the PAM matrix of amino acid substitutions (5). The robustness of the results was assessed by resampling with substitution, commonly referred to as bootstrapping (300 replicates). Branch length estimates (from dnadist or protdist) were superimposed on the consensus tree by using the fitch module within PHYLIP.

RESULTS

DNA sequence analysis.

Sequence data were obtained for 552 nucleotides (184 codons) for each of the 35 S. suis serotype type strains listed in Table 1. This region corresponds to nucleotides 744 to 1298 (555 bases, 185 codons) of the E. coli groEL sequence (accession number X07850), the E. coli sequence that contains a one-codon insertion compared to the S. suis sequence. The resulting sequences could be aligned without gaps by CLUSTALW. The resulting alignment contained 365 invariant positions out of 552. A pairwise distance matrix for DNA was calculated by using the maximum-likelihood option of the dnadist program. The pairwise distances between S. suis sequences ranged from 0 to 0.276. There were four groups of identical nucleotide sequences: those for serotypes 2, 14, and 15; those for serotypes 17 and 19; those for serotypes 18 and 23; and those for serotypes 20, 22, and 26.

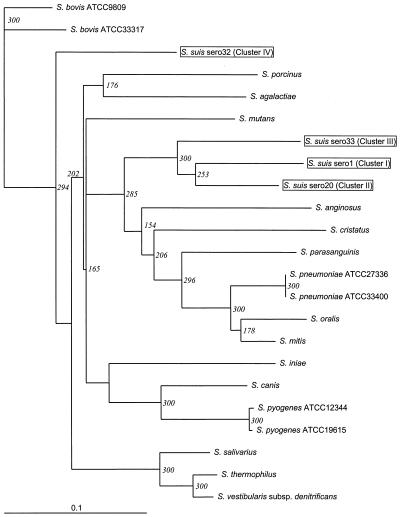

Three hundred bootstrap replicates were analyzed by the neighbor-joining method to calculate the consensus tree shown in Fig. 1. Within the phylogenetic tree, four clusters could be identified for the S. suis sequences. Cluster I comprised 29 strains whose distances from serotype 1 were less than 0.10. Cluster II contained three strains with identical sequences; the distance of these strains, the serotype 20, 22, and 26 strains, from serotype 1 was 0.135. Cluster III contained a single strain, the serotype 33 strain, whose distance from serotype 1 was 0.17, and cluster IV contained serotype 32 and 34 strains, whose distance from serotype 1 was 0.26.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic consensus tree for S. suis serotype chaperonin 60 gene partial nucleotide sequences obtained by the neighbor-joining method (300 bootstraps). Pairwise distance matrices were calculated by the maximum-likelihood option of dnadist within PHYLIP (7). The numbers at the nodes indicate the numbers of occurrences of the branching patterns in 300 runs. The horizontal lengths of the branches are proportional to the distances between sequences. The strains used and GenBank accession numbers for the chaperonin 60 gene sequences are listed in Table 1. sero, serotype.

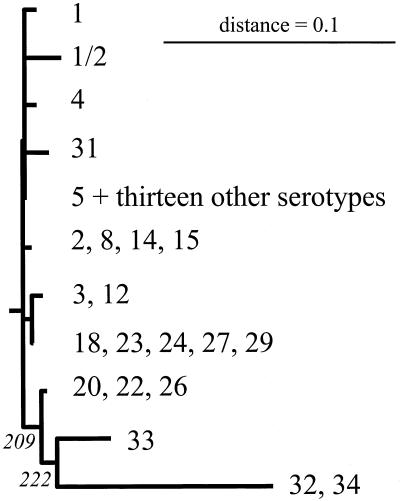

Because of the large distances between the chaperonin 60 genes of the serotype 20, 22, 26, 32, 33, and 34 strains and the chaperonin 60 genes of the rest of the strains and their clustering behavior on the S. suis phylogenetic tree, chaperonin 60 gene sequences from other Streptococcus type strains were aligned to define the relative positions of the divergent S. suis serotypes in the genus Streptococcus (Table 1). For this alignment, the following S. suis chaperonin 60 gene sequences representing the four clusters identified in Fig. 1 were used: serotype 1 for cluster I, serotype 20 for cluster II, serotype 33 (the sole member of cluster III), and serotype 32 for cluster IV. The resulting alignment was used to generate the consensus distance tree (300 bootstraps, neighbor joining) shown in Fig. 2. The chaperonin 60 gene sequence for serotype 32 grouped at a distance from the other S. suis sequences and clustered instead close to the Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus salivarius sequences.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic consensus tree for Streptococcus chaperonin 60 gene partial nucleotide sequences obtained by the neighbor-joining method (300 bootstraps). Pairwise distance matrices were calculated by the maximum-likelihood option of dnadist within the PHYLIP package (7). The numbers at the nodes indicate the numbers of occurrences of the branching patterns in 300 runs. The horizontal lengths of the branches are proportional to the distances between sequences. The strains used and sequence accession numbers are listed in Table 1. Representative serotypes for the four clusters of S. suis serotypes are enclosed in boxes. sero, serotype.

Protein sequence analysis.

Peptide translations of the partial chaperonin 60 gene sequences were produced, and the resulting peptide sequences could be aligned without gaps with CLUSTALW. Of 184 amino acids, 154 were identical in all sequences, and another 18 positions consisted of conservative amino acid changes. Pairwise distances were calculated by using a PAM 001 matrix. Many of the differences in DNA sequences observed among the serotypes were silent in terms of their effects on the encoded peptide sequence. This led to several of the protein sequences being identical, even though the DNAs encoding them exhibited substantial distances. Specifically, the protein sequences for serotypes 2, 8, 14, and 15 were identical to each other, as were those for serotypes 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, 19, 21, 25, 28, and 30 and also those for serotypes 18, 23, 24, 27, and 29. Smaller groups of identical sequences included the serotype 3 and 12 sequences, the serotype 20, 22, and 26 sequences, and the serotype 32 and 34 outlier sequences. The alignment of the 11 distinct sequences present in the 35 serotype strains was used to calculate a consensus distance tree (300 bootstraps) by the neighbor-joining method. The same four clusters identified on the DNA phylogenetic tree were easily recognized on the protein tree shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic consensus tree for representative chaperonin 60 S. suis peptide sequences obtained by the neighbor-joining method (300 bootstraps). Distances were calculated by the PAM method within the protdist software (7). The numbers at the nodes indicate the numbers of occurrences of the branching patterns in 300 runs. The horizontal lengths of the branches are proportional to the distances between sequences. The strains used and sequence accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

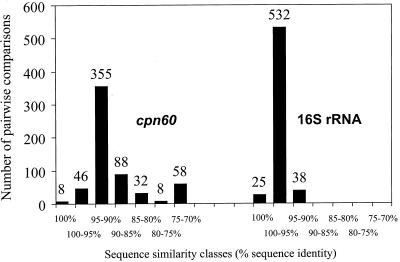

Comparison between 16S rRNA distances and chaperonin 60 gene distances.

The pairwise distances (595 values) between the chaperonin 60 gene sequences were calculated by the maximum-likelihood procedure (8) and compared to the distances between the corresponding 16S rRNA gene sequences published previously (4). The results are presented in a histogram in Fig. 4. As expected, the chaperonin 60 gene sequences for S. suis serotype strains were found to be significantly more distant (P < 0.01, sign test) from each other than the 16S rRNA sequences were; the average pairwise distance was 0.10, compared to an average 16S rRNA distance of 0.015. The chaperonin 60 gene sequences also showed greater diversity; the standard deviation was 0.06 for the complete set of 595 pairwise distances, compared to standard deviation of only 0.017 for the 16S rRNA data set. There were eight distances of 0 in the chaperonin 60 gene triangular distance matrix, compared to 25 for the 16S rRNA triangular matrix, again indicating that the chaperonin 60 gene sequences are more discriminating. The correlation coefficient for the two sets of distances was strongly positive (0.84), indicating that pairs of strains with large chaperonin 60 gene distances also tended to have large 16S rRNA differences. There was, however, one instance in which the pairwise distance between the 16S rRNA genes was actually larger than the distance between the chaperonin 60 genes. This occurred with outlier serotypes 32 and 34, for which almost identical chaperonin 60 gene sequences (distance, 0.0018) were obtained for strains that differed by 0.01 at the 16S rRNA level.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of chaperonin 60 gene (cpn60) and 16S rRNA pairwise DNA sequence identities (4) for 35 S. suis serotypes. The total number of pairwise comparisons used for each gene is 595.

Comparison between the chaperonin 60 gene and the 16S rRNA consensus trees.

The consensus tree obtained for the chaperonin 60 gene sequences showed substantial similarity to the tree obtained previously for the 16S rRNA sequences (4). Most significantly, the outlier sequences for serotypes 32, 33, and 34 branched similarly in the two trees. The sequences for serotypes 20, 22, and 26 also formed a distinct cluster in both trees. However, the sequences for serotypes 7, 9, and 30, which formed a distinct cluster in the 16S rRNA tree, were interspersed with the other sequences of the main cluster in the chaperonin 60 gene tree.

DISCUSSION

The chaperonin 60 gene phylogenetic analysis of the S. suis serotype reference strains gave results congruent with those obtained previously with 16S rRNA sequences. The greater variability of the chaperonin 60 gene sequences should help workers design specific probes for DNA microarrays that are capable of assisting in rapid identification of serotypes.

The chaperonin 60 gene results also supported the previous finding (4) based on 16S rRNA studies that serotypes 32, 33, and 34 are different from the rest of the S. suis serotypes. The observed 16S rRNA distances from serotype 1 for these serotypes ranged from 0.045 to 0.067 and correspond to chaperonin 60 gene distances of between 0.16 and 0.26, values which are much greater than the values for the rest of the type strains, for which the chaperonin 60 gene distances did not exceed 0.14. When the data were considered in terms of deviation from the average, the distance of serotypes 32 and 34 from serotype 1 was 2.6 times the average for the full set and 3.3 times the average if serotypes 32 and 34 were excluded from the set. The situation was even clearer at the protein level, at which the distances between serotypes 32 and 34 and serotype 1 were more than five times the average for the full set of pairwise distances and more than 12 times the average if serotypes 32 and 34 were excluded from the set. Notwithstanding the phenotypic homogeneity of the serotype 32 and 34 strains with the rest of the S. suis strains, it is to be expected that the former strains may eventually be reclassified in a different species. An additional finding of interest is the sequence divergence between the S. suis serotype 32 and 34 strains at the 16S rRNA level compared to their almost complete sequence identity at the chaperonin 60 gene level. Further studies of these strains are needed to explore the possibility of horizontal transfer of the chaperonin 60 gene between S. suis strains, as well as the alternative explanation that different copies of the 16S rRNA genes were amplified in serotypes 32 and 34.

The results of this study demonstrate that the chaperonin 60 gene variable-region sequences provide superior discrimination between closely related strains compared to the 16S rRNA sequences and at the same time produce results which closely parallel those of a 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis. The resolving power of the chaperonin 60 gene sequences, coupled with the fact that these sequences can be amplified with universal primers located in the conserved regions, should prove to be useful in establishing molecular diagnosis and identification methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by funds from the Canadian Biotechnology Strategy and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

The use of computer facilities provided by the Canadian Bioinformatics Resource (http://www.cbr.nrc.ca) is gratefully acknowledged. The help of Agnès Renoux (Biotechnology Research Institute, Montreal, Canada) with statistical analysis is also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beaudoin M, Harel J, Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Frenette M, MacInnes J I. Molecular analysis of isolates of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 by restriction-endonuclease-digested DNA separated on SDS-PAGE and by hybridization with an rDNA probe. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2639–2645. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boye M, Feenstra A A, Tegtmeier C, Andresen L O, Rasmussen S R, Bille-Hansen V. Detection of Streptococcus suis by in situ hybridization, indirect immunofluorescence, and peroxidase-antiperoxidase assays in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections from pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12:224–232. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chanter N, Jones P W, Alexander T J. Meningitis in pigs caused by Streptococcus suis — a speculative review. Vet Microbiol. 1993;36:39–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90127-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatellier S, Harel J, Zhang Y, Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Devriese L A, Brousseau R. Phylogenetic diversity of Streptococcus suis strains of various serotypes as revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequence comparison. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:581–589. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dayhoff M O, Schwartz R M, Orcutt B C. A model of evolutionary change in proteins. In: Dayhoff M O, editor. Atlas of protein sequence and structure. 5, suppl. 3. Washington, D.C.: National Biomedical Research Foundation; 1978. pp. 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devriese L A, Ceyssens K, Hommez J, Kilpper-Balz R, Schleifer K H. Characteristics of different Streptococcus suis ecovars and description of a simplified identification method. Vet Microbiol. 1991;26:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90050-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.51c). Seattle: University of Washington; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goh S H, Driedger D, Gillett S, Low D E, Hemmingsen S M, Amos M, Chan D, Lovgren M, Willey B M, Shaw C, Smith J A. Streptococcus iniae, a human and animal pathogen: identification by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2164–2166. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2164-2166.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh S H, Facklam R R, Chang M, Hill J E, Tyrrell G J, Burns E C, Chan D, He C, Rahim T, Shaw C, Hemmingsen S M. Identification of Enterococcus species and phenotypically similar Lactococcus and Vagococcus species by reverse checkerboard hybridization to chaperonin 60 gene sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3953–3959. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.3953-3959.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh S H, Potter S, Wood J, Hemmingsen S M, Reynolds R P, Chow A W. Hsp60 gene sequences as universal targets for microbial species identification: studies with coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:818–823. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.818-823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh S H, Santucci Z, Kloos W E, Faltyn M, George C G, Driedger D, Hemmingsen S M. Identification of Staphylococcus species and subspecies by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method and reverse checkerboard hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3116-3121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottschalk M, Segura M. The pathogenesis of the meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis: the unresolved questions. Vet Microbiol. 2000;76:259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Jacques M, Mittal K R, Henrichsen J. Description of 14 new capsular types of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2633–2635. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2633-2636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottschalk M, Higgins R, Jacques M, Beaudoin M, Henrichsen J. Characterization of six new capsular types (23 through 28) of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2590–2594. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2590-2594.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottschalk M, Lacouture S, Odierno L. Immunomagnetic isolation of Streptococcus suis serotypes 2 and 1/2 from swine tonsils. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2877–2881. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2877-2881.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R S. Evolution of the chaperonin families (Hsp60, Hsp10 and Tcp-1) of proteins and the origin of eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hampson D J, Trott D J, Clarke I L, Mwaniki C G, Robertson I D. Population structure of Australian isolates of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2895–2900. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2895-2900.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harel J, Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Bigras-Poulin M. Genomic relatedness among reference strains of different Streptococcus suis serotypes. Can J Vet Res. 1994;58:259–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins R, Gottschalk M. Distribution of Streptococcus suis capsular types in 1998. Can Vet J. 1999;40:277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Boudreau M, Lebrun A, Henrichsen J. Description of six new capsular types (29–34) of Streptococcus suis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1995;7:405–406. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilpper-Bälz R, Schleifer K H. Streptococcus suis sp. nov., nom. rev. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwok A Y C, Su S C, Reynolds R P, Bay S J, Av-Gay Y, Dovichi N J, Chow A W. Species identification and phylogenetic relationships based on partial HSP60 gene sequences within the genus Staphylococcus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1181–1192. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohtsuka E, Matsuki S, Ikehara M, Takahashi Y, Matsubara K. An alternative approach to deoxyoligonucleotides as hybridization probes by insertion of deoxyinosine at ambiguous codon positions. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:2605–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perch B, Pedersen K B, Henrichsen J. Serology of capsulated streptococci pathogenic for pigs: six new serotypes of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:993–996. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.6.993-996.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guadinium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith H E, Rijnsburger M, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Wisselink H J, Vecht U, Smits M A. Virulent strains of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and highly virulent strains of Streptococcus suis serotype 1 can be recognized by a unique ribotype profile. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1049–1053. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1049-1053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith H E, Veenbergen V, van der Velde J, Damman M, Wisselink H J, Smits M A. The cps genes of Streptococcus suis serotypes 1, 2, and 9: development of rapid serotype-specific PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3146–3152. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3146-3152.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staats J J, Plattner P L, Nietfeld J, Dritz S, Chengappa M M. Use of ribotyping and hemolysin activity to identify highly virulent Streptococcus suis type 2 isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:15–19. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.15-19.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignments through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]