Abstract

Cells of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens contain two types of morphologically distinct crystalline inclusion proteins. The larger rectangular inclusion (type 1) and a smaller bipyramid-shaped inclusion (type 2) were purified from cell lysates by differential centrifugation and isopycnic density gradient centrifugation. Both structures are composed of protein and are readily soluble at pH 11 and 4 in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and in 8 M urea. Electrophoretic analysis reveals that each inclusion is composed of a single protein subunit with a molecular mass of 11,000 Da. The proteins differ in amino acid composition, protease digestion pattern, and immunological cross-reactivity. The protein inclusions are first visible in the cells at the time of late exponential growth. Western blot analyses showed that the proteins appeared in cells during mid- to late exponential growth. When at maximum size in stationary-phase cells, the proteins constitute 40% of the total cellular protein. The protein inclusions are not used during long-term starvation of the cells and were not toxic when injected into or fed to Galleria mellonella larvae.

Photorhabdus luminescens is a bioluminescent gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that was first isolated from a light-emitting insect that had been infected by entomogenous nematodes of the family Heterorhabditidae (22, 29). Biochemical tests and analysis of the 16S rRNA revealed that P. luminescens is related to members of the Enterobacteriaceae in the gamma subdivision of purple bacteria (13, 31, 32).

The bacteria reside in the intestinal tract of the infective juvenile (IJ) stage of the nematode, which is the vector for transmission of the bacteria between insect prey. The IJ penetrates the insect, releasing the bacteria into the hemolymph. The bacteria multiply rapidly, killing the insect within 24 to 72 h, at which time the dead insect is visibly bioluminescent (23, 25, 29). A 50% lethal dose (LD50) of fewer than 5 cells per insect has been reported for Galleria mellonella (wax moth) larvae (15). The bacterium produces potent insecticidal toxins during growth in the insect as well as in laboratory culture (9, 21). The nematode completes several rounds of reproduction while feeding on the bacteria in the insect carcass. Within 10 to 20 days several thousand IJ progeny, each carrying an inoculum of P. luminescens cells, migrate out of the cadaver in search of new insect prey.

Cells of P. luminescens growing in insect larvae and in culture medium produce phase-bright inclusion proteins within the cytoplasm (7, 23). Bacteria of the related genus Xenorhabdus, associated with entomogenous nematodes of the family Steinernematidiae, also produce two cytoplasmic inclusion proteins (11). The genes encoding two inclusion proteins, cipA and cipB, of P. luminescens strain NC1 have been cloned and characterized (5). The genes are present at separate loci and show little nucleotide sequence similarity to each other. Blast searches using the nucleotide or amino acid sequences of the two genes reveal little evidence of homology to any known genes, including those encoding the insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis.

Cultures of P. luminescens exhibit a highly variable phenotype involving the spontaneous loss of many traits. The variants, termed secondary-phase cells, differ from the original primary phase in colony morphology, dye absorption, and biochemical utilization and show complete loss of or decrease in antibiotic production, pigmentation, bioluminescence, protease activity, lipase activity, hemolysin production, and the ability to support nematode growth (1, 2, 6, 12, 14, 27). The intracellular inclusion proteins are absent in the secondary phase cells (5).

The function of the inclusion proteins of Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus is unknown. Because both genera of bacteria are entomopathogens and are associated in a symbiosis with entomopathogenic nematodes, logical hypotheses are that the inclusion proteins are involved in the nematode association or in pathogenesis. The cost of producing the unusually large amounts of these proteins strongly suggests that the proteins must serve an important function for the bacteria.

This report describes the isolation and characterization of the two protein inclusions from P. luminescens NC1 and Hm and presents the results of attempts to define their function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and culture conditions.

The inclusion proteins were purified from P. luminescens strains Hm (G. M. Thomas, University of California) and NC1 (Wayne Brooks, University of North Carolina). Stock cultures were maintained on 2% proteose peptone no. 3 (PP3) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) solidified with 1.5% Bacto agar (Difco). Cultures were incubated at 30°C for 72 h, stored at room temperature, and transferred at monthly intervals. Two stable secondary-phase variants were isolated from the primary-phase NC1. They are referred to as white secondary (nonpigmented) and yellow secondary (yellow pigmentation).

Microscopy.

Phase-contrast micrographs were taken with a Zeiss photomicroscope using Kodak technical pan film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N.Y.). For the time-lapse study, cells from a 48-h culture were incubated at 30°C on a thin layer of PP3 agar on a sterile microscope slide and covered with an oxygen-permeable Teflon membrane. For transmission electron microscopy, the cells were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, embedded in Duracupan (Sigma), thin sectioned, and stained with lead citrate. The sectioned cells were viewed under a Jeol-100CX electron microscope. For scanning electron microscopy, purified inclusions were suspended in sterile water (sH2O), placed on double-stick tape on a steel post, dried, and coated with gold in vacuo. The samples were examined with a Hitachi S-570 scanning electron microscope.

Optimization of inclusion production.

The conditions for optimum inclusion production in liquid culture (all culture media from Difco) were determined by growing cells in 5% yeast extract, 2% neopeptone, 2% casitone, 2% proteose peptone no. 3, 2.5% nutrient broth, 10% peptone, or 2% Trypticase at 30°C. Cells were examined after 72 h by phase-contrast microscopy.

Isolation of inclusions.

A 2-ml suspension of P. luminescens cells in 2% PP3 broth was spread on 2% PP3 agar in Pyrex glass baking dishes (18 by 30 cm). After 7 days of incubation at 28°C, 100 ml of sH2O was added, and the cells were scraped from the agar surface with a bent glass rod. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (sPBS) consisting of (per liter) NaCl (8.0 g), KCl (0.20 g), Na2HPO4 (1.15 g), and KH2PO4 (0.2 g) (18) and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of sPBS and passed twice through a French press at 10,000 lb/in2. The cell lysate was diluted to 50 ml in sPBS and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 20 min. This step was repeated three times.

The chalky white pellets that were produced were resuspended in 9 ml of sPBS, and 3-ml samples were applied to the top of discontinuous Percoll (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) density gradients (28). The Percoll solutions were prepared from a stock solution containing 1 part 2.5 M sucrose and 9 parts (vol/vol) Percoll. Step gradients consisted of a 5-ml layer of Percoll stock solution placed at the bottom of 30-ml Corex centrifuge tubes, followed by application of sequential layers of 95, 90, 80, and 70% dilutions of the stock solution. Following centrifugation (4 h at 5,000 × g) in a Sorvall type HS-4 swinging bucket rotor at 4°C, the two visually distinct inclusion-containing layers were removed separately and washed several times in sH2O by centrifugation at 2,000 × g. Each fraction was then centrifuged through the gradients once more as described. The purified inclusions were stored as frozen pellets at −20°C, lyophilized, and stored under desiccation at room temperature or in sH2O at 4°C.

Solubility of inclusions.

A suspension of purified inclusions was made in sH2O at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 2.0. The pH of samples were adjusted by slowly adding 1.0-μl amounts of 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH, and the OD600 of the suspensions was monitored. To determine solubility in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 100 μl of 10% SDS (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.) was added to 900 μl of inclusion suspension. To determine solubility in urea or EDTA, inclusions were resuspended in 1 ml of 8 M urea or 100 mM EDTA at pH 8.0.

Compositional analysis and total inclusion protein content of cells.

The protein content of inclusions was determined by the Lowry assay (16), and the carbohydrate content was estimated by the anthrone reaction (16). Total amino acid composition was determined at the Biotechnology Instrumentation facility of the University of California–Riverside, using the Beckman 120C amino acid analysis system. The percentage of inclusion protein in the cells was determined using 7-day-old cells scraped from agar plates. The washed cells were disrupted using a French pressure cell. The protein content of the lysate was determined. The inclusions were then collected from the lysate by centrifugation and washed twice with sH2O and subsequent centrifugation, and the protein content of the pelleted inclusions was determined. The percentage of inclusion proteins in the cell was calculated as [(milligrams of inclusion protein)/(milligrams of lysate protein)] × 100.

Mass spectrometry.

Mass determinations were performed at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center on a Bruker Biflex III matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer.

Protease digestion of intact inclusions.

The protein inclusions were digested with trypsin (Sigma Chemical Co.), V-8 protease from Staphylococcus aureus (Miles Scientific, Naperville, Ill.), and two different pronase preparations (Calbiochem). Each digestion reaction contained 1.8 mg of the pure type 1 or 2 protein inclusions suspended in 0.9 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, to which was added 0.2 mg of protease dissolved in 0.1 ml of the same buffer. The samples were digested at 37°C for 4 h on a rocking platform. Five-microliter samples were then mixed with SDS sample loading buffer, boiled for 5 min, and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as described below.

Production of antisera.

The density gradient-purified type 1 and 2 inclusion proteins from NC1 were used to immunize New Zealand White rabbits. Prior to emulsification in adjuvant, 500 μg of each inclusion protein was solubilized in 1 ml of 10 mM NaOH. Freund's complete adjuvant was used for the primary immunizations, and Freund's incomplete adjuvant was used for three additional injections made at monthly intervals. Serum obtained 10 days after the final injections was heated to 56°C for 15 min to inactivate complement and stored at −20°C (18).

Time course of inclusion production.

Cells were grown for 16 h at 30°C in 25 ml of 2% PP3 broth in a 125-ml flask shaken at 250 rpm. Five milliliters of this culture was used to inoculate 250 ml of 2% PP3 broth in a 1-liter flask, which was also shaken at 250 rpm at 30°C. At various times, samples were removed and washed in sH2O, and the total protein content of the cells was determined. The samples were adjusted to 200 μg of protein per ml, and 10-μl samples (2 μg of total protein) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Secondary-phase cells grown for 96 h at 30°C in 25 ml of 2% PP3 broth in a 125-ml flask with shaking at 250 rpm were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blot analyses.

Cells and purified inclusion proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis using a protocol designed for high resolution of proteins in the 5- to 30-kDa range (33). Proteins were stained with 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. For Western blot analysis, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes in 25 mM Tris–192 mM glycine and 20% (vol/vol) methanol. The gels were electroblotted for 1 h at 20 V constant voltage in a Genie Blotter (Ideas Scientific, Minneapolis, Minn.). The AuroProbe BLplus and IntenSE BL silver enhancement kit (Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, Ill.) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions to detect antigen on the blots. The primary antibody was used at a 1:1,000 dilution.

Stability of inclusion proteins during growth and starvation.

Cells were grown for 48 h at 30°C in 50 ml of 2% PP3 broth in 500-ml flasks shaken at 250 rpm. Samples were removed at various times, and microscopic counts were determined using a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber. Viable-cell counts were determined by dilution of samples into fresh 2% PP3 broth, plating on 2% PP3 agar, and counting colonies after 5 days of incubation at 30°C. For starvation experiments, the 48-h PP3 cultures were divided into two 25-ml portions. One sample was transferred to a 250-ml flask and incubated as above. The other sample was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were resuspended in 25 ml of sPBS and incubated as above. Samples were removed from the flasks, and microscopic counts and viable-cell counts were determined at various times.

Insect toxicity analyses.

G. mellonella larvae were obtained from H. C. Coppel (Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin–Madison) and grown by his method (26). Samples containing 25 μg of purified type 1 or 2 proteins in 10 μl of sH2O were either fed to or injected into last instar G. mellonella larva (9). The inclusion proteins were also solubilized with 10 mM HCl or 10 mM NaOH, filter sterilized with 0.2-μm-pore-sized membrane filters, and then fed or injected. Samples (cells plus broth) taken directly from 48-h PP3 cultures were also fed to and injected into larvae. Freshly prepared (stored at 4°C) and frozen inclusion preparations were used for bioassays.

RESULTS

Production and isolation of inclusion proteins.

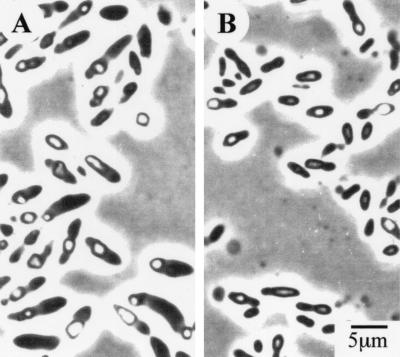

A variety of liquid culture media were tested for their effect on inclusion production by both P. luminescens strains NC1 and Hm. The inclusions were visibly evident using phase-contrast microscopy in most cells of both strains after 48 h of growth in 2.5% nutrient broth and 2% neopeptone. Approximately half the cells contained inclusions when grown in 2% Trypticase soy broth. The cells grew well but produced no visible inclusions when grown in 2% casitone, 5% yeast extract, or 10% peptone. The best growth medium, in which more than 90% of the cells contained phase-bright inclusions, was 2% PP3. Photomicrographs of cells of strains NC1 and Hm grown on 2% PP3 agar reveal the presence of phase-bright inclusions in the cells (Fig. 1A and 1B).

FIG. 1.

Phase-contrast photomicrographs of P. luminescens cells grown for 7 days on PP3 agar. (A) P. luminescens strain NC1. (B) P. luminescens strain Hm. Magnification, ×2,560.

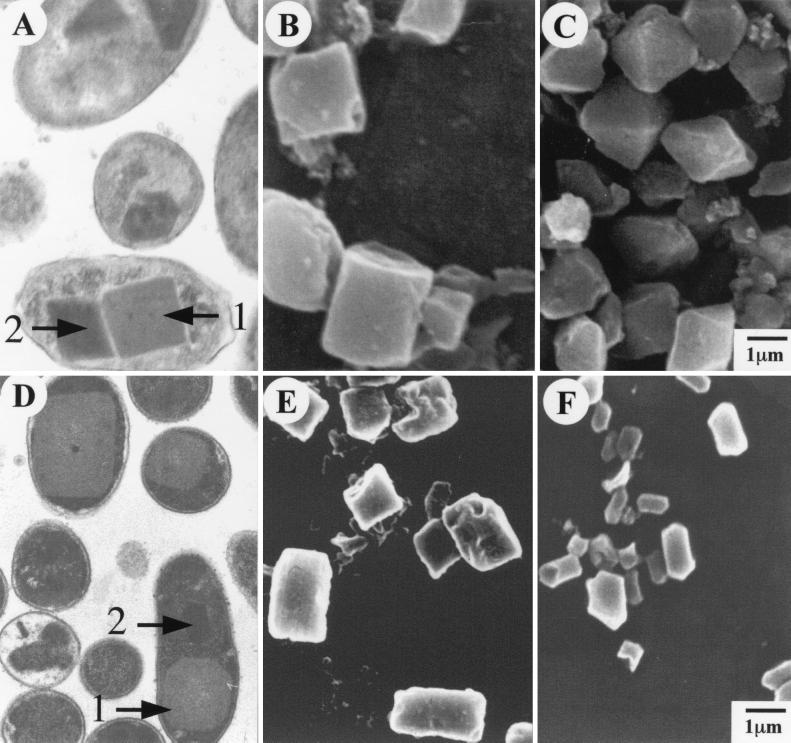

Transmission electron micrographs of thin-sectioned cells of NC1 and Hm show that both these strains contain two morphologically distinct inclusions (Fig. 2A and 2D) The protein inclusions released from cells by French pressure breakage became separated into two bands in the Percoll gradients. Scanning electron micrographs of Percoll-separated inclusions show the less dense type 1 inclusion to be rectangular (Fig. 2B and 2E). The morphology of the more dense type 2 inclusions of NC1 and Hm differs. The NC1 type 2 is bipyramidal (Fig. 2C), and the Hm type 2 has pointed ends and is elongated in the middle (Fig. 2F).

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrograph of thin sections of cells of P. luminescens NC1 (A) and Hm (D) showing that cells contain two distinct inclusion protein structures. Scanning electron micrographs of protein inclusions separated by density gradient centrifugation. (B and C) Type 1 and 2 inclusions of NC1, respectively; (E and F), type 1 and 2 inclusions of Hm, respectively.

Solubility, compositional analyses, and mass spectrometry.

The purified type 1 and type 2 inclusions from both strains are insoluble in water and at neutral pH in PBS or Tris buffer. The effect of pH on the solubility of the inclusion structures was tested by slowly increasing and decreasing the pH of an aqueous suspension. The inclusion structures remained insoluble between pH 5 and 10. The OD600 of the suspension decreased by more than 90% at pH 11 or 4; at both pHs, the inclusions become soluble. As the pH was slowly adjusted from 4 and 11 toward neutrality, the solutions became cloudy at pH 5 and pH 7, respectively, coincident with the formation of an amorphous precipitate. Both types of inclusions were soluble (greater then 90% OD600 decrease) in 8 M urea and 1% SDS. The inclusions were not soluble in 100 mM EDTA.

Both type 1 and 2 inclusion structures are composed entirely of protein, with no detectable carbohydrate, even when a 10-mg (dry weight) sample of inclusions was analyzed. The MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer analyses confirmed the absence of glycosylation on the proteins.

The results of amino acid composition analyses of type 1 and type 2 protein inclusions of strains NC1 and Hm are shown in Table 1. The amino acid compositions of the type 1 and type 2 inclusion proteins of strains NC1 and Hm obtained by compositional analysis are similar and correlate closely with the composition predicted for the cipA and cipB gene products of the Hm strain (5). The molecular weights predicted from the amino acid composition are NC1 type 1, 10,578; NC1 type 2, 10,648; Hm type 1, 10,574; and Hm type 2, 10,700. The amino acid compositions of the two protein inclusions are quite different, however. The type 1 protein inclusion contains 0 to 1% cysteine, 1 to 2% methonine, 20 to 24% leucine, and 4% lysine. The type 2 protein contains 4 to 5% cysteine, 13% methonine, 9 to 11% leucine, and 9 to 10% lysine. The type 1 protein contains approximately 47% hydrophobic amino acids, while the type 2 protein contains approximately 42% hydrophobic amino acid residues, with particularly high levels of valine, methonine, isoleucine, and leucine.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid composition of P. luminescens Hm and NC1 protein inclusions compared to the amino acid composition predicted from the Hm cipA and cipB gene sequences

| Amino acida | No. of residues per subunit

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hm type 1

|

NC1 type 1b | Hm type 2

|

NC1 type 2b | |||

| Analysisb | cipBc | Analysisb | cipAd | |||

| Lysine* | 4 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| Histidine* | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Phenylalanine* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leucine* | 20 | 18 | 24 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| Isoleucine* | 10 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 6 |

| Threonine* | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Methionine* | 2 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Valine* | 14 | 16 | 16 | 9 | 10 | 9 |

| Arginine* | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Tyrosine* | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Aspartate/asparagine | 15 | 13 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 12 |

| Serine | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Glutamate/glutamine | 6 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Proline | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Glycine | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Alanine | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Cysteine | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Trytophan | NDe | 0 | ND | ND | 1 | ND |

| Total | 94 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 104 | 93 |

The amino acid compositional analysis obtained by acid hydrolysis of the proteins followed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) showed four lysine residues in the type 1 inclusion of both NC1 and Hm. This value differs from the 14 lysine residues predicted by the Hm gene sequence (5). Most likely this difference is due to an unexplained error in the compositional analyses.

The percentage of total cell protein attributable to the inclusion proteins is approximately 40% in the 7-day-old cultures.

The density gradient-purified inclusions from both strains were analyzed by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). The results show that the inclusions are composed almost entirely of a single-molecular-mass species. The molecular mass of the type 1 inclusion of the Hm strain is 11,323 Da, which is nearly identical to the predicted mass of 11,315 Da for the cipB gene product of strain Hm. The molecular mass of NC1 type 1 is 11,381 Da and is very close to the molecular mass of the Hm type 1 inclusion. The molecular masses of the Hm and NC1 type 2 inclusions are 11,711 and 11,697 Da, respectively, which is nearly identical to the predicted 11,700 Da of the cipA gene product.

The mass spectrometry data for the type 2 inclusions of both strains show a minor shoulder peak indicating components 42 mass units larger for the NC1 and 47 mass units larger for the Hm inclusions. This mass shift suggests that a small percentage of the protein may contain a posttranslational modification; most likely it is acetylated.

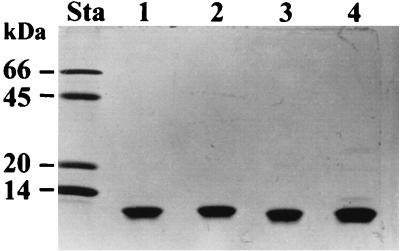

SDS-PAGE analysis and proteolytic degradation.

The results of SDS-PAGE analysis of the protein inclusions show that both type 1 and type 2 protein inclusions from strains NC1 and Hm are apparently composed of single proteins that each have a molecular mass of approximately 10 kDa (Fig. 3). This value correlates well with the mass estimated from amino acid analyses and mass estimates for the inclusion proteins.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis (18% gel) of density gradient-purified protein inclusions from P. luminescens strains Hm and NC1. Lane Sta, molecular size markers (2 μg of protein per band); lane 1, Hm type 1 protein inclusions; lane 2, Hm type 2 protein inclusions; lane 3, NC1 type 2 protein inclusions; lane 4, NC1 type 1 protein inclusions. Each protein inclusion sample contained 3 μg of total protein.

The degree of proteolytic digestion of type 1 and type 2 inclusions of NC1 by four different proteases was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The type 1 protein inclusion was extensively degraded by two different pronase preparations, was cleaved into two discrete fragments by trypsin, and was not hydrolyzed by the V8 protease. The type 2 protein inclusion was only slightly degraded by the pronase preparations, and most of the protein remained as a single intact band that was not degraded by trypsin or V8 protease (not shown). Inclusions present in cell lysates of both strains were also analyzed for degradation by indigenous cellular proteases. The cell lysates contained high levels of proteolytic activity, but degradation was not detected in suspensions of inclusions incubated in the lysates for as long as 1 week (not shown).

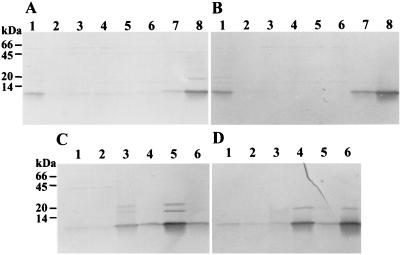

Immunological analysis and temporal regulation of inclusion protein accumulation.

Polyclonal antisera raised against type 1 and type 2 inclusion proteins of NC1 were used to determine the time of inclusion protein production in growing cells. Western blot analyses (Fig. 4A and B) revealed that both type 1 and 2 proteins are first detected at 16 h (lanes 7, panels A and B). Both proteins reached high levels in 24-h cells (lanes 8). The inclusion protein detected at 0 h (lanes 1, A and B) resulted from the stationary-phase cells used as the inoculum. During the first 12 h of growth, the inclusion proteins were diluted relative to the total protein content of the cells. Microscopic examination of the cells confirmed that the protein inclusions were first visible at 16 h of growth. By 24 h, greater than 70% of the cells contained small inclusions (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

(A and B) Western blot analyses of time of appearance during growth of P. luminescens NC1 type 1 and 2 protein inclusions. (A) Cell lysates probed with type 1 inclusion antiserum. (B) Cell lysates probed with type 2 inclusion antiserum. Lanes 1, 0-h cells (inoculum); lanes 2, 6-h cells; lanes 3, 8-h cells; lanes 4, 10-h cells; lanes 5, 12-h cells; lanes 6, 14-h cells; lanes 7, 16-h cells; lanes 8, 24-h cells. (C and D) Western blot analyses of gradient-purified inclusions and cell lysates from secondary-phase cells. (C) Probed with type 1 inclusion antiserm. (D) Probed with type 2 inclusion antiserum. Lanes 1, 96-h NC1 yellow secondary cells; lanes 2, 96-h NC1 white secondary cells; lanes 3, type 1 protein inclusions from strain Hm; lanes 4, type 2 protein inclusions from strain Hm; lanes 5, type 1 protein inclusions from NC1; lanes 6, type 2 protein inclusions from NC1. Cell lysate lanes contain 2 mg of total protein. Purified protein inclusion lanes contain 0.1 mg of total protein.

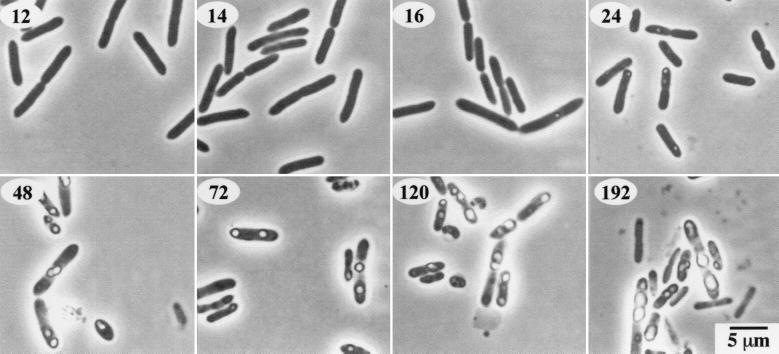

FIG. 5.

Phase-contrast photomicrographs of cells of P. luminescens strain NC1 grown in PP3 broth and during starvation. The first inclusions are visible at 16 h (numbers on the photomicrographs indicate time [in hours] after inoculation of the culture). After 48 h of growth in PP3, the cells were centrifuged, resuspended in sPBS, and returned to the shaker. The inclusions remain present at all times after the shift to starvation conditions (72 to 192 h).

Two secondary-phase variants were isolated from the primary NC1 strain. The white secondary was deficient in all characteristics typical of primary-phase cells. The yellow secondary-phase variant was deficient in all characteristics except pigmentation and antibiotic production. Both secondary variants contained no visible inclusions (not shown). Western blot analyses did not detect inclusion proteins in the secondary-phase variants (Fig. 4C and 4D, lanes 1 and 2).

The type 1 and type 2 NC1 antisera were used to analyze the immunological cross-reactivity of the inclusion proteins from strains NC1 and Hm (Fig. 4C and 4D). Type 1 antiserum cross-reacts weakly with NC1 type 2 protein (Fig. 4C, lane 6) but strongly recognizes a 10-kDa band, and reacts more weakly with two proteins of approximately 20 and 30 kDa in the NC1 type 1 material (Fig. 4C, lane 5). Type 2 antiserum cross-reacts weakly with NC1 type 1 protein (Fig. 4D, lane 5) but strongly recognizes a 10-kDa band and more weakly a protein of approximately 20 kDa in the type 2 lane (Fig. 4D, lane 6). The cross-reactivity and banding patterns produced by the type 1 and 2 antisera with NC1 inclusion proteins were nearly identical to the results obtained for the Hm inclusion proteins (Fig. 4C and 4D, lanes 3 and 4). The higher-molecular-weight bands detected by the antisera may be multimers of the individual subunits of each inclusion type, since their migration distances are consistent with those of a dimer and a trimer of the individual proteins. If this conclusion is correct, these multimers occur even in the presence of SDS.

Are the protein inclusions nutrient reserves?

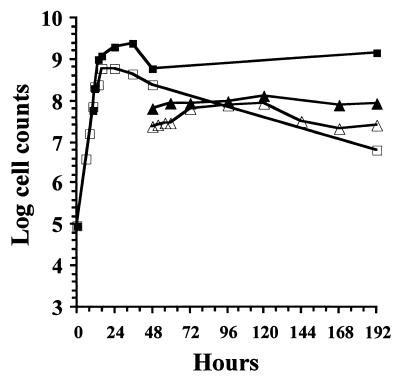

The possibility that the protein inclusions might serve as a reserve nutrient source for the bacteria was tested. The cells contained visible cytoplasmic protein inclusions at 16 h (Fig. 5). Growth in 2% PP3 broth reached maximum levels between 24 and 36 h (Fig. 6). The direct microscopic counts reached a maximum level of 5 × 109 cells/ml at 36 h. The viable-cell counts reached a maximum of 8 × 108 cells/ml at 24 h and decreased steadily until only about 1% of the cells (107/ml) were viable at 192 h. Protein inclusions were still visible in most of the cells at 192 h. The cells starved in sPBS generally remained viable up to 192 h. The ratio of microscopic counts to viable plate counts remained nearly constant throughout the starvation period (Fig. 6), and during this time the protein inclusions in the cells were not noticeably reduced in size (Fig. 5).

FIG. 6.

Growth and starvation of P. luminescens NC1. Cells were incubated at 30°C in a shake flask in 2% PP3. At 48 h, a portion of the culture was removed, centrifuged, washed, resuspended in sPBS (starved), and returned to the shaker. Microscopic counts and viable-cell counts were determined at various times after inoculation. Symbols: ■, PP3 microscopic count: □, PP3 viable count; ▴, starved microscopic count; ▵, starved viable count.

Protein inclusions in dividing cells.

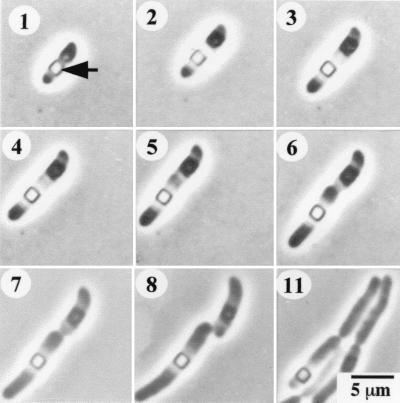

A possible explanation for the loss in viability of late-stationary-phase cells is that the large protein inclusions in the cytoplasm might interfere with cell division. This possibility is unlikely to be the case, because time-lapse phase-contrast micrographs clearly show that a cell with a large inclusion is capable of cell division (Fig. 7). The cell elongates and divides on either side of the inclusion. The inclusion protein remains visible inside the mother cell through several rounds of division. This result also shows that inclusion proteins are not detectably degraded and consumed by dividing cells.

FIG. 7.

Time-lapse photomicrographs of P. luminescens cells growing on slide culture of PP3 agar. Numbers at the upper left of each frame are the incubation time (in hours).

Toxicity of protein inclusions.

The intact and solubilized P. luminescens protein inclusions did not kill G. mellonella larvae. This was true for both frozen and freshly isolated inclusions. Injection of larvae with several thousand viable P. luminescens cells from a 48-h culture killed the larvae in 24 h.

DISCUSSION

Cells of P. luminescens strains NC1 and Hm each contain two distinct intracellular protein inclusions that can constitute up to 40% of the total cell protein. The proteins are nearly identical in molecular size and solubility properties but differ significantly in amino acid content, susceptibility to protease digestion, and immunological cross-reactivity. The unusually high content of hydrophobic amino acids in the two protein classes (47% for type 1 and 42% for type 2) probably accounts for their insolubility at neutral pH and solubility at alkaline and acidic pH.

The mass spectrometry and SDS-PAGE analyses show that each inclusion type is composed of a single protein subunit. The mass spectrometry data also showed that the NC1 type 1 inclusion is approximately 66 mass units larger than the Hm type 1. This is probably due to minor differences in the amino acid composition of the proteins. All of these analyses combined with the amino acid composition analyses show that the type 1 inclusion is the cipB gene product and the type 2 inclusion is the cipA gene product (5).

The biological function of the inclusion proteins is not known. One possibility suggested by the interesting analogy to the parasporal insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis (3, 18, 19) is that the proteins are involved in insect toxicity of P. luminescens. Feeding and injection of G. mellonella larvae with both the native and solubilized inclusion proteins did not support this hypothesis. Insect larvae are highly susceptible to the intact bacterial cells; the injected lethal dose is 10 to 100 cells. Similarly, secondary-phase cells that contain no intracellular protein inclusions are equally virulent when injected into larvae (5).

Another plausible function for the proteins is involvement in the nematode symbiosis. The Heterorhabditis nematodes grow and multiply while feeding on the primary-inclusion-containing cells, but do not grow and multiply with the secondary-phase cells that lack inclusion proteins. The entomopathogenic nematode Neoplectana (Steinernema) glaseri requires 10 amino acids for growth (20), and these 10 amino acids account for more than 60% of the amino acids in the protein inclusions. The type 2 inclusion protein is especially rich in methionine, which constitutes 13% of the total amino acids. This level of methionine is unusual; the average methionine content of a collection of 207 proteins is 1.7% (22). Thus, intracellular protein inclusions might serve as a rich supply of essential amino acids for the nematode, although there is no known evidence for the nematodes' obtaining these amino acids from the inclusions. If the protein inclusions are degraded by enzymes in the nematode intestine and are essential to nematode development, the nematodes would be expected to grow on killed cells. In preliminary studies, we found that the nematodes do not grow and reproduce on heat-, freeze-thaw-, or UV light-killed primary-stage cells that contain protein inclusions (unpublished observations). The requirement for living P. luminescens cells for nematode development indicates that the nature of the association between the two organisms is a complex interaction in which the inclusion proteins may be just one factor. Two mutants of P. luminescens, each missing just one of the inclusion proteins, did not support nematode growth (5). However, these mutants also acquired some secondary-phase characteristics, which could also explain the inability to support nematode growth. Further evidence that this symbiosis is a complex interaction is the report that a transposon-mediated mutation in a phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene of P. luminescens NC1 results in cells that no longer supported growth and reproduction of the nematodes (10). This mutant produced both the protein inclusions.

The observation that culture broth of P. luminescens NC1 contains bacteriocins and phage particles was the basis of speculation that they may be related to the cytoplasmic inclusions (4). The P. luminescens strain NC1 used in this study also produced both of these particles (S. Bintrim, unpublished observations). Western blot analyses using both type 1 and type 2 antisera did not detect any immunologically related material in the culture broth which contained these phage-like structures (unpublished observations).

The inclusions do not appear to be energy or amino acid reserves. The inclusion proteins were not degraded is starving cells (Fig. 6), and cells incubated on agar media or in broth media for several months retained the inclusions.

Another bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophilus, is symbiotically associated with the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae (30). This bacterium, which is related to Photorhabdus in some characteristics but clearly belongs to a different genus (8), also produces two intracellular crystal proteins (11). The sizes of these proteins, as estimated by SDS-PAGE analyses, were 22 and 26 kDa, which is twice the size of the P. luminescens proteins. The X. nematophilus protein inclusions are similar in some solubility characteristics to the P. luminescens protein inclusions; for example, they are insoluble at neutral pH but soluble at acidic and alkaline pH, but differ in being soluble in 5 mM EDTA, while both of the P. luminescens protein inclusions were insoluble at concentrations of up to 100 mM EDTA. Couche et al. suggested that the inclusion proteins of X. nematophilus might be associated with nematode growth and reproduction, but no supporting data were presented (11).

It is interesting that two different genera of bacteria involved in a symbiotic relationship with two different families of entomopathogenic nematodes both produce two intracellular protein inclusions. Because the proteins differ in size and other important aspects, it is likely that the two organisms developed this property independently, although perhaps for a common purpose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds from the S. C. Johnson Wax Co. and by a USDA Hatch Grant from the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhurst R J. Morphological and functional dimorphism in Xenorhabdus spp. bacteria symbiotically associated with the insect pathogenic nematodes Neoaplectana and Heterorhabdus. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;121:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhurst R J. Antibiotic activity of Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with insect pathogenic nematodes of the families Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:3061–3065. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-12-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang B J, Nickerson K W. Purification of the protein crystal from Bacillus thuringiensis by zonal gradient centrifugation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;36:625–625. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.4.625-626.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baghdiguian S, Boyer-Giglio M, Thaler J, Bonnot G, Boemare N. Bacteriocinogenesis in cells of Xenorhabdus nematophilus and Photorhabdus luminescens: Enterobacteriaceae associated with entomopathogenic nematodes. Biol Cell. 1993;79:177–185. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bintrim S B, Ensign J C. Insertional inactivation of genes encoding the crystalline inclusion proteins of Photorhabdus results in mutants with pleiotropic phenotypes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1261–1269. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1261-1269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleakly B, Nealson K H. Characterization of primary and secondary forms of Xenorhabdus luminescens strain Hm. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1988;53:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boemare N E, Louis C, Kuh G. Étude ultrastructurale des crisaux chez Xenorhabdus spp. bacteries infodées aux nematodes entomophages Steinernematidae et Heterorhabditidae. C R Soc Biol. 1982;177:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boemare N E, Akhurst R J, Mourant R G. DNA relatedness between Xenorhabdus spp. (Enterobacteriaceae), symbiotic bacteria of entomopathogenic nematodes, and a proposal to transfer Xenorhabdus luminescens to a new genus, Photorhabdus gen. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:249–255. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowen D J, Ensign J C. Purification and characterization of a high-molecular-weight insecticidal protein complex produced by the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3029–3035. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.3029-3035.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciche T A, Bintrim S B, Horswill A R, Ensign J C. A phosphopantetheinyl transferase homolog is essential for Photorhabdus luminescens to support growth and reproduction of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3117–3126. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3117-3126.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couche G A, Gregson R P. Protein inclusions produced by entomopathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5279–5288. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5279-5288.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehlers R, Stossel S, Wyss U. The influence of phase variants of Xenorhabdus spp. and Escherichia coli (Enterobacteriaceae) on the propagation of entomopathogenic nematodes of the genera Steinernema and Heterorhabditis. Rev Nematol. 1990;13:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehlers A, Wyss U, Stackebrandt E. 16s rRNA cataloging and the phylogenetic position of the genus Xenorhabdus. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1988;10:121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerritsen L J M, DeRaay G, Smits P H. Characterization of forms variants of Xenorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1975–1979. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1975-1979.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giffin C T, Simons W R, Smits P H. Activity and infectivity of Heterorhabditis spp. J Invertebr Pathol. 1989;53:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen R S, Phillips J A. Chemical composition. In: Gerhardt P, editor. Manual of methods for general bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1981. pp. 328–364. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofte H, Whitely H R. Insecticidal crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:242–255. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.242-255.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson L, Hay F C. Practical immunology. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1980. p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibara J E, Federici B A. Isolation of a relatively nontoxic 65-kilodalton protein inclusion from the paraporal body of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. J Bacteriol. 1956;165:527–533. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.2.527-533.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson G J. Neoplectana glaseri: essential amino acids. Exp Parasitol. 1973;34:111–114. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(73)90068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaroz J, Balcerzak M, Skrzypek H. Involvement of larvicidal toxin in pathogenesis of insect parasitism with the Rhabditoid nematodes Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. Entomophaga. 1991;36:361–368. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan A, Brooks W M, Hirschmann H. Chromonema heliothidis n. gen., n. sp. (Steinernematidae, Nematoda), a parasite of Heliothis zea (Noctuidae, Lepidoptera) and other insects. J Nematol. 1976;8:159–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan A, Brooks W. A chromogenic bioluminescent bacterium associated with the entomophilic nematode Chromonema heliothidis. J Invertebr Pathol. 1977;29:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klapper M H. Frequency of occurrence of each amino acid residue in the primary structures of 207 unrelated proteins of known sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;78:1018–1024. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90523-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milstead J E. Heterorhabditis bacteriophora as a vector for introducing its associated bacterium into the hemocoel of Galleria mellonella larvae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1979;33:324–327. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed M A, Coppel H C. Mass rearing of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), for small-scale laboratory studies. Great Lakes Entomol. 1983;16:139–141. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul V J, Frautschy S, Fenical W, Nealson Antibiotics in microbial ecology: isolation and structure assignment of several new antibacterial compounds for insect-symbiotic bacteria Xenorhabdus spp. J Chem Ecol. 1981;7:589–597. doi: 10.1007/BF00987707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pharmacia Fine Chemicals. Percoll methodology and applications. Uppsala, Sweden: Pharmacia Fine Chemicals; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poinar G O., Jr Description and biology of a new insect parasitic rhabditoid, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora n. gen., n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae n. fam.) Nematologica. 1975;21:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poinar G O, Thomas G M. Significance of Achromobacter nematophilus in the development of the nematode DD-136. Parasitology. 1966;56:385–390. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000070980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poinar G O, Thomas G M, Hess R. Characteristics of the specific bacterium associated with Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (Heterorhabditidae: Rhabditida) Nematologica. 1977;23:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas G M, Poinar G O. Xenorhabdus gen. nov., a genus of entomopathogenic nematophilic bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1979;29:352–360. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas J O, Kornberg R D. Chemical cross linking of histones. Methods Cell biol. 1978;18:429–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]