Abstract

Two 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes, Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181, were developed for specific detection of the acidophilic methanotroph Methylocella palustris using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The fluorescence signal of probe Mcell-181 was enhanced by its combined application with the oligonucleotide helper probe H158. Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181, as well as 16S rRNA oligonucleotide probes with reported group specificity for either type I methanotrophs (probes M-84 and M-705) or the Methylosinus/Methylocystis group of type II methanotrophs (probes MA-221 and M-450), were used in FISH to determine the abundance of distinct methanotroph groups in a Sphagnum peat sample of pH 4.2. M. palustris was enumerated at greater than 106 cells per g of peat (wet weight), while the detectable population size of type I methanotrophs was three orders of magnitude below the population level of M. palustris. The cell counts with probe MA-221 suggested that only 104 type II methanotrophs per g of peat (wet weight) were present, while the use of probe M-450 revealed more than 106 type II methanotroph cells per g of the same samples. This discrepancy was due to the fact that probe M-450 targets almost all currently known strains of Methylosinus and Methylocystis, whereas probe MA-221, originally described as group specific, does not detect a large proportion of Methylocystis strains. The total number of methanotrophic bacteria detected by FISH was 3.0 (±0.2) × 106 cells per g (wet weight) of peat. This was about 0.8% of the total bacterial cell number. Thus, our study clearly suggests that M. palustris and a defined population of Methylocystis spp. were the predominant methanotrophs detectable by FISH in an acidic Sphagnum peat bog.

Until very recently, the list of recognized methanotrophic bacteria (MB) encompassed eight genera. These genera are divided into two physiologically distinct MB groups, type I and type II methanotrophs, which form phylogenetically coherent clusters in the γ- and α-subclasses of the class Proteobacteria, respectively. The genera Methylomonas, Methylobacter, Methylococcus, Methylomicrobium, Methylocaldum, and Methylosphaera (6, 8, 9, 32) belong to the type I MB, while the genera Methylosinus and Methylocystis (32) represent the traditionally known group of type II MB. Last year a novel acidophilic methanotroph was described, Methylocella palustris (15). Strains of M. palustris were isolated from acidic Sphagnum peat bogs (14) and classified as type II MB. However, phylogenetically they were only moderately related to the known type II MB and were more closely affiliated with the heterotrophic bacterium Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica.

The isolation of Methylocella palustris from Sphagnum bogs of different geographical locations (four different sites in west Siberia and European north Russia) suggests that these bacteria might be widely distributed in acidic wetlands of the northern hemisphere. These wetlands are considered an important source of atmospheric methane (23). However, information on the distribution and abundance of Methylocella in northern wetlands is still lacking. As the result of their profound distinctness from other known methanotrophs, these organisms have not been targeted by the culture-independent 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA)-based molecular approaches developed for detection of type I and type II MB (12, 33). This is also true for the retrieval of the pmoA gene, which encodes the active-site polypeptide of particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO), as M. palustris is the first MB for which pmoA could not be detected using a PCR assay considered universal for this gene (15). Although M. palustris possesses an mmoX gene, coding for the α subunit of the soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) and thus can be detected by the mmoX-based approach, this assay is not universal for MB, as only some of them possess sMMO. Thus, effective methods for the in situ detection of Methylocella were not available until now.

One of the most powerful tools in modern microbial ecology is fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). FISH allows the specific detection and enumeration of target populations directly in their natural environment without the need for cultivation (3, 4). Although FISH is potentially very useful for studies of methanotroph ecology (28), reports on the enumeration of indigenous methanotroph populations by FISH have not yet been published. So far, FISH-based techniques have only been applied for the analysis of MB in mixed and enrichment cultures (7, 20, 31). A number of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes have been developed for specific detection of type I and type II MB (7, 10, 16, 20, 31). However, none of the currently available probes targets Methylocella palustris. Thus, the primary goal of our study was the development of oligonucleotide probes for the specific detection of these novel acidophilic methanotrophs. The newly developed probes and those of reported group specificity for either type I MB or the Methylosinus/Methylocystis group of type II MB were further applied to determine the abundance of distinct methanotroph groups in a Sphagnum peat (pH 4.2) from west Siberia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Methylocella palustris K (ATCC 700799T), Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (ATCC 35070T), Methylococcus capsulatus (NCIMB 11853), Methylomicrobium album (NCIMB 11123), and Methylobacter luteus (NCIMB 11914) were used in this study. The last three strains represent subcultures of the corresponding National Collections of Industrial, Food, and Marine Bacteria strains and were kindly provided by G. Eller (Max-Planck-Institut für terrestrische Mikrobiologie, Marburg, Germany). Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica (ATCC 9039T), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (DSM 30131T), and Azorhizobium caulinodans (DSM 5975T) were used as nontarget control strains. M. palustris K was grown on twice-diluted nitrogen-sufficient M1 medium supplemented with vitamins (15), under a gas headspace containing 20% methane (vol/vol). The cultures were shaken at 120 rpm at 24°C. All other methanotrophs were cultivated on NMS medium (32) under the same conditions. The only exception was Methylococcus capsulatus, which was incubated at 37°C with 40% methane (vol/vol) in the headspace. Beijerinckia indica was cultivated on nitrogen-free mineral medium supplemented with glucose (5). Azorhizobium caulinodans and Bradyrhizobium japonicum were grown on the media recommended by the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany) catalogue. To ensure constant exponential growth and a high cell ribosome content, all cultures were serially transferred at least three times prior to harvesting.

Methane-oxidizing enrichment cultures.

Four methane-oxidizing consortia enriched from acidic Sphagnum peat bogs of different geographic locations were used in FISH with newly developed oligonucleotide probes. The characteristics of these enrichments as well as the cultivation conditions used were described previously (13).

Peat sample.

The Sphagnum peat sample was collected from a depth of 10 to 15 cm of an acidic peat (pH of 3.6 to 4.5) underlying a Sphagnum-Carex plant community (Bakchar bog, Plotnikovo field station in west Siberia, 56°N, 82°E). The original sample was transported to the laboratory and divided in two parts. The first subsample was fixed immediately as described below, while the other was incubated for 1 month under 10% methane and then fixed.

Fixation procedure. (i) Bacterial strains and methane-oxidizing enrichments.

Cells growing in the logarithmic phase were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing, in grams per liter, NaCl, 8.0; KCl, 0.2; Na2HPO4, 1.44; and NaH2PO4, 0.2 (pH 7.0). Cell suspensions were mixed with 1.5 ml of 4% (wt/vol) freshly prepared paraformaldehyde solution (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and fixed for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then collected by centrifugation (6,600 × g for 1 min) and washed twice with PBS to ensure removal of paraformaldehyde. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of 50% ethanol-PBS (vol/vol), and the cell suspension was stored at −20°C until use.

(ii) Peat samples.

Two grams of wet Sphagnum peat was placed into a disposable 50-ml syringe with some sterile cotton glass covering the exit hole. The plunger was replaced and pressed to extract water from the peat. This treatment allowed us to separate the peat water enriched with microbial cells from the rough Sphagnum debris. Approximately 0.5 ml of peat water was mixed with 1.5 ml of 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde solution and fixed as described above. The rest of the peat material was mixed with 20 ml of sterile water and homogenized in a laboratory stomacher (model 80, Seward Medical Limited, London, United Kingdom) at 265 rpm for 1 min, and the water was again extracted with a syringe. The fraction obtained was designated the peat matrix fraction and was centrifuged (5,000 rpm) for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended with sterile water up to a final volume of 2 ml. An aliquot (0.5 ml) of this suspension was used for paraformaldehyde fixation. To assess the efficacy of the cell extraction from peat, the stomacher treatment (see above) was repeated two additional times and two additional peat matrix fractions were obtained. The rest of the peat material was cut into very small fragments (<0.5 mm) with scissors. The two additional peat matrix fractions and 50 mg of the small peat fragments were fixed as described above.

Oligonucleotide probes.

Potential 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes applicable to the specific detection of Methylocella palustris were formulated using the probe design tool of the ARB program package (developed by O. Strunk and W. Ludwig; available online at http://www.arb-home.de). Based on the 16S rRNA database included in the ARB program package, the probe design tool selects nucleotide sequence regions that allow discrimination of target sequences from all nontarget reference sequences. The final selection of suitable target sites was done using the in situ accessibility map of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA (18). According to the probe nomenclature (1), the newly designed probes were designated S-S-Mcell-1026-a-A-18 (Mcell-1026) and S-S-Mcell-0181-a-A-18 (Mcell-181). For use in FISH, the probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181 were labeled with indocarbocyanine dye (Cy3) and 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FLUOS), respectively. For enhancement of the fluorescence signal of probe Mcell-181, the oligonucleotide helper probe H158 was developed and used in combination with Mcell-181. Depending on the experimental setup, the bacterial probe EUB338 fluorescently labeled with either Cy3 or FLUOS was used (2). The probes with reported group specificity for either type I MB or type II MB, i.e., probes M-84, M-705, M-450, and MA-221 (7, 16), were applied in FISH with Cy3 label. Oligonucleotide probes were purchased from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). Probe sequences, target sites, formamide concentrations in the hybridization buffer, hybridization temperature, and sodium chloride concentrations in the washing buffer used for FISH are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide probes used in this study

| Probe | Specificity | Probe sequence (5′-3′) | Target sitea (16S rRNA positions) | % Formamide in bufferb | Hybridization tempb(°C) | NaCl in wash buffer (mM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | Bacteria | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | 338–355 | 0 | 46 | 900 | 2 |

| MA-221 | Type II MB | GGACGCGGGCCGATCTTTCG | 221–240 | 35* | 55* | 80 | 7 |

| M-450 | Type II MB | ATCCAGGTACCGTCATTATC | 450–470 | 30* | 46 | 112 | 16 |

| M-84c | Type I MB | CCACTCGTCAGCGCCCGA | 84–103 | 20 | 46 | 225 | 16 |

| M-705c | CTGGTGTTCCTTCAGATC | 705–724 | |||||

| Mcell-1026 | M. palustris | GTTCTCGCCACCCGAAGT | 1026–1043 | 0 | 45–50 | 900 | This study |

| Mcell-181 | M. palustris | TCTTTCTCCTTGCGGACG | 181–198 | 0 | 45–50 | 900 | This study |

| H158d | M. palustris | GGTATTAATCCAAGTTTC | 158–175 | 0 | 45–50 | 900 | This study |

Position numbers refer to the E. coli 16S rRNA sequence.

*, Optimal hybridization conditions determined in this study.

Probes M-84 and M-705 have been used in conjunction.

Helper probe.

Whole-cell hybridization.

Hybridization was done on 70% ethanol-rinsed and dried Teflon-coated slides with eight wells for independent positioning of the samples. Approximately 2 μl of the fixed cell suspension was spread on each well, air dried, and dehydrated by successive passages through an ethanol series (50, 80, and 100% [vol/vol]) for 3 min each. A 50-ml polypropylene screw-top Falcon tube containing a slip of Whatman filter paper soaked in hybridization buffer was used as a hybridization chamber as described by Stahl and Amann (29). The chamber was allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 min at the hybridization temperature. A 9-μl aliquot of hybridization buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and formamide concentrations as given in Table 1) was placed on each spot of fixed cells. The slide was transferred to the equilibrated chamber and prehybridized for 30 min. Following prehybridization, 1 μl of fluorescent probe solution (50 ng of probe per μl in double-distilled water) was added to each spot, and the slide was returned to the hybridization chamber for 2 h. Then, slides were washed at the hybridization temperature for 10 min in washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.01% SDS, and NaCl at the concentrations given in Table 1) and rinsed with twice-distilled water. The slides were air dried, stained with the universal DNA stain 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 2 μM) for 10 min in the dark, rinsed again with distilled water, and finally air dried. Each well of the slide was mounted with a drop of Citifluor AF1 antifadent (Citifluor Ltd., Canterbury, United Kingdom), covered with a coverslip and viewed immediately.

Two negative controls were also prepared for each test sample. One of these controls (lacking a probe) was used to determine the autofluorescence of cells, while the other was applied to assess potential nonspecific binding, i.e., the two probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181 were used in combination with nontarget reference organisms.

Optimization of hybridization conditions.

Two approaches were used to optimize the hybridization conditions. These were (i) gradually increasing the hybridization stringency by the addition of formamide to the hybridization buffer in 5% (vol/vol) steps (22) and (ii) increasing the hybridization temperature from 30 to 70°C in 5°C steps without formamide in the hybridization buffer. In each case hybridization was performed with M. palustris and nontarget organisms displaying the smallest number of mismatches within the target region (Fig. 1). Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica and Azorhizobium caulinodans were used as nontarget organisms for probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181, respectively.

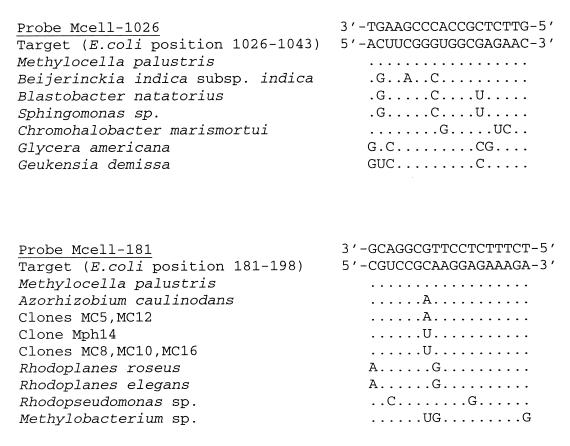

FIG. 1.

Alignment of 16S rRNA target regions of probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181. The three currently known strains of M. palustris, strains K, S6, and M131 (14, 15), exhibit identical target regions for the two probes. The alignment shows those bacterial reference species and environmental clone sequences which display the smallest number of mismatches in the target region of Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181. The GenBank accession numbers for the environmental clones MC5, MC8, MC10, MC12, MC16, and Mph14 are X65581, X65576, X65579, X65577, X65575, and U58013, respectively.

Quantitative FISH procedure.

The slides with fixed peat fractions were simultaneously hybridized with Cy3-labeled Mcell-1026 and FLUOS-labeled Mcell-181. Special attention was paid to make sure that target cells were hybridized with both probes. However, the high background fluorescence due to a large amount of semidecomposed Sphagnum material made it difficult to use the FLUOS-labeled probe for enumeration of MB. In contrast, bacteria hybridized with the Cy3-labeled probe stood out sharply against the background. Thus, cell counting of M. palustris was performed on preparations hybridized with Cy3-labeled Mcell-1026. In addition, the number of cells stained with the bacterial probe EUB338, type I MB probes M-84 and M-705, and type II MB probes M-450 and MA-221 were determined. Cell counting was performed on 100 randomly chosen fields of view (FOV) for each test sample. The number of target cells per gram of wet peat was determined from the area of the sample spot, the area of the FOV, the volume of the fixed sample used for hybridization, and the volume of the peat water extracted (PWE) from the sample as follows: total number of target cells per gram of peat = (mean target cell number per FOV × area of sample spot × total volume of the fixed sample × total volume of the PWE)/(area of FOV × volume of the fixed sample applied × dilution × PWE aliquot taken for fixation × peat sample weight).

Total cell counts.

Total cell counts from peat samples were obtained by DAPI staining (see above). Dilutions that resulted in approximately 20 to 200 cells per FOV were used. The total cell number in 100 randomly chosen FOV was determined as described above.

Microscopy.

Cells were counted with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with the following filter sets: HQ light filter AHF/AF 41001 (AHF Analysentechnik, Tübingen, Germany) for FLUOS-labeled probes (excitation 460 to 500 nm, emission 510 to 560 nm), AHF/F 41007 for Cy3-labeled probes (excitation 510 to 560 nm, emission 572.5 to 642.5 nm), and Zeiss Filter 02 for DAPI staining (excitation 365 nm, long-pass emission 420 nm). Color micrographs were made on Fujichrome Provia 1600 ASA color reversal film. Exposure times were 0.04 to 0.06 s for phase contrast and 30 to 60 s for epifluorescence micrographs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Probe design.

Two probes, Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181, each targeting a unique region of the 16S rRNA of Methylocella palustris, were developed based on the public domain 16S rRNA data set and the probe design tool of the ARB program package. The specificity of the two newly designed probes was also confirmed using the probe match tool of the Ribosomal Database Project (21). The sequence of probe Mcell-1026 matched the sequences of all three known strains of Methylocella palustris but exhibited at least three mismatches to all other currently available 16S rRNA reference sequences (Fig. 1). The probe Mcell-181 had one mismatch (A:G at position 187) with the 16S rRNA sequence of Azorhizobium caulinodans, while all other nontarget reference sequences from cultured organisms displayed at least two mismatches to this probe (Fig. 1). Consequently, Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica and Azorhizobium caulinodans, whose 16S rRNA sequences showed the smallest number of mismatches in the target region to the probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181, respectively, were chosen as negative control strains for optimization of the probe hybridization conditions.

Helper probe.

Initial tests showed that Cy3-labeled probe Mcell-1026 provided higher signal intensity with M. palustris K than Cy3-labeled EUB338, yielding a high resolution for environmental studies. In contrast, the FLUOS-labeled Mcell-181 probe showed a lower intensity signal than did FLUOS-labeled EUB338. In order to enhance the fluorescence signal of Mcell-181, three potential helper oligonucleotides (H158, H159, and H160) were designed (17). Each of the three oligonucleotides targeted a 16S rRNA region that was adjacent to the target site of probe Mcell-181. Their use in conjunction with Mcell-181 showed that one of them, H158, caused a detectable increase in the probe-conferred signal (results not shown). Thus, in the following studies, probe Mcell-181 was always used in combination with H158. The H158 probe sequence and the corresponding target site are shown in Table 1.

Optimization of hybridization conditions for Methylocella-specific probes.

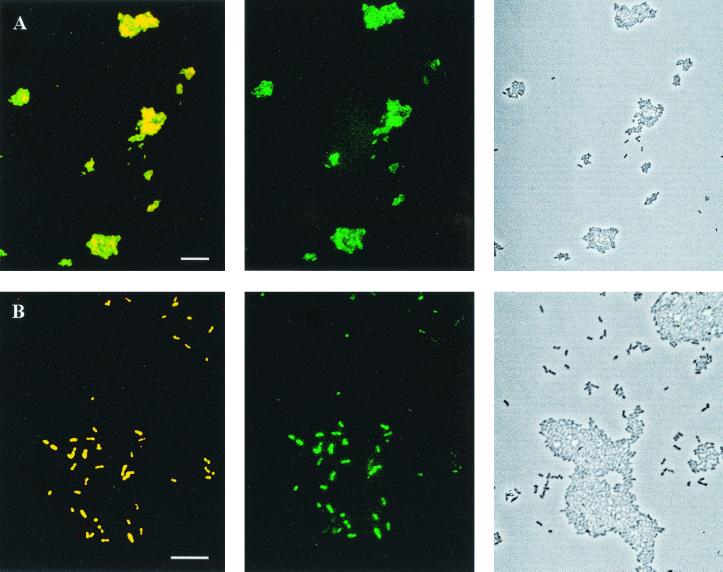

An attempt was made to determine optimal hybridization conditions for the probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181 by the conventional approach. In this approach, the hybridization stringency is increased by increasing the concentration of formamide in the hybridization buffer (22). The range of formamide concentrations used was from 0 to 40%, in 5% increments. However, we observed that formamide clearly inhibited the whole-cell hybridization of Methylocella palustris K with all fluorescent probes tested, including EUB338. Simultaneous application of fluorescently labeled probes Mcell-1026 and EUB338 confirmed that the higher the formamide concentration used in the hybridization buffer, the fewer cells were detectable by FISH. However, without formamide in the hybridization buffer all cells were stained with both probes Mcell-1026 and EUB338 (Fig. 2). At formamide concentrations above 20%, most cells of M. palustris K remained unstained regardless of the temperature used for hybridization. This observation was confirmed using several batches of formamide purchased from different companies (Fluka, Merck, Serva, and Sigma). However, we did not observe any negative effect of formamide on whole-cell hybridization of the other methanotroph species tested (Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b, Methylococcus capsulatus, Methylomicrobium album, and Methylobacter luteus). Similarly, the use of formamide did not show any negative effect on whole-cell hybridization of nontarget control strains (Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica and Azorhizobium caulinodans) or of some other bacteria (E. coli, Corynebacterium sp., and Bacillus sp.) with EUB338.

FIG. 2.

Whole-cell hybridization of Methylocella palustris K with and without formamide in the hybridization buffer. The phase-contrast images are shown on the right side, the epifluorescence micrographs of whole-cell hybridization with probes Mcell-1026 (yellow) and EUB338 (green) are on the left side and in the middle, respectively. (A) No formamide; (B) 10% formamide in the hybridization buffer. The scale bar (10 μm) applies to each row of images.

For specific detection of M. palustris, formamide was therefore excluded from the hybridization buffer, and the optimal hybridization conditions were determined by increasing the hybridization temperature in 5°C steps. For Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181, the probe-conferred fluorescence signal intensity increased with increasing hybridization temperature up to 50°C, then decreased with further temperature increase, and almost disappeared at 70°C. At temperatures above 40°C, Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181 did not show any nonspecific signals in hybridization experiments with nontarget control strains. Regardless of the hybridization conditions used, cells of Methylocella palustris K did not exhibit any autofluorescence. Consequently, the optimal hybridization temperature range that provided high target specificity was 45 to 50°C.

Evaluation of 16S rRNA probes with reported group specificity for type II MB.

We assessed whether the probes MA-221 and M-450 (Table 1) showed any nonspecific hybridization with M. palustris. The probes MA-221 and M-450 exhibit three and two mismatches, respectively, with the 16S rRNA sequence of M. palustris and, as expected, did not show any binding to cells of M. palustris under any of the hybridization conditions used. A weak nonspecific signal was observed if probe M-450 was applied to cells of Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica under the hybridization conditions reported in the original publication (20% formamide, 46°C) (16). Thus, we used probe M-450 under slightly higher stringency conditions (30% formamide, 46°C). The probe MA-221 had one terminal mismatch (G:U at position 240) to 16S rRNA sequences of numerous nonmethanotrophic bacteria, including Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Nitrobacter winogradskyi, Blastobacter denitrificans, Agromonas oligotrophica, and Photorhizobium thompsonianum. Whole-cell hybridization of Bradyrhizobium japonicum with MA-221 showed that the stringency conditions reported in the original publication (10% formamide, 37°C) (7) did not allow discrimination of B. japonicum from type II MB of the Methylosinus/Methylocystis group. Target specificity for probe MA-221 was achieved at 35% formamide and 55°C.

Analysis of methanotrophic consortia enriched from Sphagnum peat bogs.

The Methylocella-specific probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181 and probes with reported group specificity for type I MB (M-84 and M-705) and type II MB (MA-221 and M-450) were used to analyze four methanotrophic consortia enriched from different Sphagnum bogs on nitrogen-sufficient and nitrogen-free media (13). Whole-cell hybridization revealed that cells of Methylocella palustris were present only in those enrichments obtained on nitrogen-sufficient media (enrichments from Sosvyatskoe, Kyrgyznoye, and Krugloye peat bogs). This result is to be expected, given that the three known strains of Methylocella palustris (S6, K, and M131) were isolated from these three enrichment cultures (14). Likewise, failure to detect Methylocella cells in the fourth methanotrophic enrichment, which was obtained on nitrogen-free medium from Bakchar bog in west Siberia, is reasonable given our failure to isolate Methylocella from the Bakchar consortium or to detect mmoX in DNA of this enrichment. Target cells of type I MB-specific probes (M-84 and M-705) and of type II MB-specific probe MA-221 were not observed in any of the four acidophilic enrichments. The application of probe M-450 detected some type II MB in only the enrichment obtained from Krugloye peat bog. These findings are in good agreement with the results of mmoX-based analyses reported previously (13). Only the DNA of the Krugloye bog enrichment yielded mmoX clones related to the Methylocystis group. The fact that none of the methanotroph-targeted probes used in this study detected MB in the Bakchar enrichment may indicate that hitherto unknown acidophilic methanotrophs are present in this consortium.

Application of FISH to native Sphagnum peat.

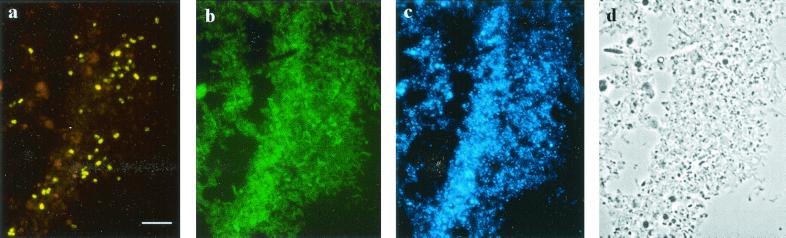

The Cy3-labeled Mcell-1026 probe in conjunction with FLUOS-labeled EUB338 and DAPI staining was applied to the peat water extracted from a Sphagnum sample. Numerous cells of Methylocella palustris were detected in peat water, and the rRNA content of cells was high enough to allow their detection (Fig. 3). The target cells were present in almost every FOV, allowing a statistically valid counting procedure.

FIG. 3.

Specific detection of Methylocella palustris in a peat sample by FISH. Pictured are epifluorescence micrographs of in situ hybridization with probes Mcell-1026 (a) and EUB338 (b), DAPI staining (c), and the phase-contrast image (d). The scale bar (10 μm) applies to all images.

Evaluation of cell extraction procedure.

Peat is one of the most problematic environmental samples for FISH-based studies due to intensive autofluorescence of organic compounds (19). In addition, Sphagnum peat contains a large amount of nondecomposed organic material and cannot be prepared as a completely homogenized slurry. We attempted to circumvent these problems by a newly developed procedure, which is based on serial cell extraction from peat (see Materials and Methods).

To evaluate the efficacy of cell extraction by this procedure, we used a peat subsample that had been enriched with methanotrophs by a 1-month incubation under 10% methane. The total cell numbers (DAPI staining) and the numbers of cells targeted by EUB338 and Mcell-1026 were determined in successive fractions obtained from this subsample (Table 2). The first two fractions (peat water fraction and peat matrix fraction obtained after the first round of homogenization and extraction) accounted for about 87% of the cells detected by DAPI staining and hybridization with EUB338 and for about 97% of the cells detected by hybridization with the Mcell-1026 probe. Three repeated cycles of homogenization-extraction led to the extraction of almost all cells (about 99%) from this peat subsample, as the cell number in the rest of the peat did not exceed 1% of the total cells detected. The application of Mcell-1026 did not reveal any cells of Methylocella palustris retained in the remaining peat after three cycles of the extraction procedure. Thus, the peat water fraction and the first peat matrix fraction can be considered sufficient for cell quantification by DAPI staining and FISH-based enumeration of methanotrophs in peat.

TABLE 2.

Cell numbers in different fractions obtained from Sphagnum peat samplea

| Detection method | No. of cells (106 or 107) per g of wet peat

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peat water fraction | Peat matrix fraction:

|

Remaining peat | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| DAPI staining (107) | 19.68 ± 1.63 | 24.87 ± 3.77 | 5.30 ± 0.81 | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.05 |

| EUB338 (107) | 13.10 ± 1.26 | 15.53 ± 2.52 | 4.10 ± 0.90 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

| Mcell-1026 (106) | 1.68 ± 0.23 | 1.21 ± 0.16 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | Nd |

Values are means ± standard error. Nd, not detected.

Quantification of acidophilic MB in peat by FISH.

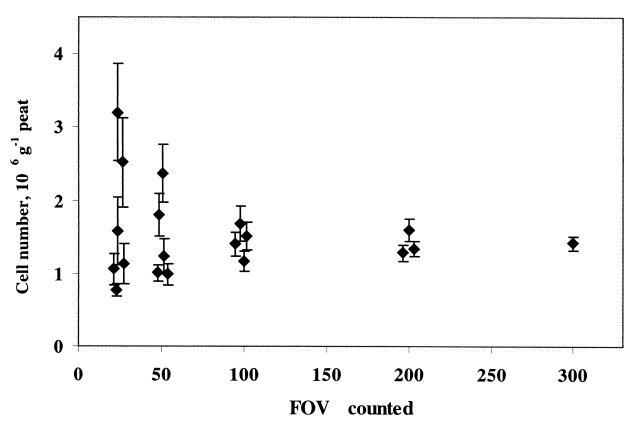

The number of microscopic FOV that need to be examined for a statistically valid quantification of MB in peat was determined experimentally. The water fraction extracted from the peat subsample enriched with MB (see above) was used for this assessment. The numbers of cells detected with Mcell-1026 were determined for 300 FOV, and both the average cell numbers and the corresponding standard error values were calculated for the randomly chosen 25, 50, 100, 200, and 300 FOV (Fig. 4). Low error values and almost the same average cell numbers were obtained for the 100, 200, and 300 FOV treatments, while the corresponding values calculated for the 25 and 50 FOV treatments showed significant variations and high error values. Thus, it was concluded that examination of 100 FOV is sufficient for a statistically valid quantification of methanotroph cells in a peat sample.

FIG. 4.

Average cell numbers of Methylocella palustris and the corresponding standard error values as a function of the number of microscopic FOV examined.

Effect of formamide on enumeration of acidophilic MB in native peat.

The negative effect of formamide on whole-cell hybridization of Methylocella palustris K in pure culture was also observed for its in situ detection in native peat. A peat sample was used for FISH without and with formamide (5 and 10%) in the hybridization buffer. The three hybridization treatments were performed using the same stringency conditions: the treatment without formamide was carried out at 50°C, while the two treatments with formamide in the hybridization buffer were carried out at 47 and 43°C. The hybridization treatment with probe Mcell-1026 and without formamide led to the detection of 1.2 (±0.1) × 106 cells per g of wet peat. An increasing concentration of formamide in the hybridization buffer resulted in a decreasing number of acidophilic MB detectable by FISH. The number of M. palustris cells detected by FISH with 5 and 10% formamide was only 24 and 2%, respectively, of the cell number detected without formamide in the hybridization buffer.

To clarify whether the observed phenomenon is of general relevance for bacteria inhabiting peat, we performed a similar experiment on total bacterial cells, encompassing for each of the hybridization treatments quantification by DAPI staining and FISH with EUB338. The hybridization treatments were carried out with (10 and 20%) and without formamide in the hybridization buffer. The hybridization temperatures were adjusted to apply the same stringency conditions to all three hybridization treatments. As expected, the numbers of DAPI-stained bacteria were the same in all three treatments. The numbers of cells detected by FISH with EUB338 were slightly lower for the treatments with formamide in the hybridization buffer than for those without it, but these differences were not statistically significant. For example, the number of cells detected with EUB338 in peat water was 1.66 (±0.22) × 108 and 1.56 (±0.22) × 108 cells per g of wet peat for the treatments without and with 20% formamide in the hybridization buffer, respectively. As the result, the percentage of DAPI-stained cells detected with EUB338 was also slightly higher for the treatments without formamide (83.2 and 56.7% for peat water and peat matrix fractions, respectively) than with 20% formamide (78.2 and 55.7%, respectively).

The mechanism of the negative effect of formamide is uncertain, given that in most previously reported cases the addition of formamide up to its optimal concentration resulted in a clear improvement in both probe sensitivity and specificity. Formamide is widely used in hybridization studies because it has been demonstrated that every 1% increase in formamide concentration reduces the melting point of double-helix structures by 0.7°C (24). This allows hybridization at lower temperatures without loss of stringency and an increase in the life time of nucleic acids by eliminating degradation that occurs at high temperatures (29). Also, the optimization of the hybridization conditions by addition of formamide to the hybridization buffer is convenient. We are not aware of any other report on possible negative effects of formamide in hybridization studies. However, the negative effect on whole-cell hybridization of Methylocella palustris was confirmed repeatedly for both pure culture and environmental samples and was reproducible with supplies of formamide purchased from different companies. As no statistically significant decrease in bacterial cell numbers was observed for Sphagnum peat after hybridization with EUB338 in the presence of formamide, the negative formamide effect might be a special feature of M. palustris. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the hybridization efficiency, defined as the proportion of total bacterial cells which were detected with EUB338, was slightly lower for the hybridization treatments with formamide than without it, and thus, it cannot be excluded that some particular bacterial populations may escape detection by FISH.

FISH-based analysis of indigenous methanotrophs inhabiting Sphagnum peat.

The Methylocella-specific probes and several fluorescent probes targeting distinct methanotroph groups (Table 1) were applied to a native peat sample. In situ hybridization with probes Mcell-1026 and Mcell-181 revealed that M. palustris was present at a relatively high abundance (1.2 (±0.1) × 106 cells per g of wet peat), and that the cells were present in roughly equal numbers in the peat water and peat matrix fractions. By contrast, probes M-84 and M-705, which target most known genera of type I MB, failed to detect any numerically significant population of these organisms in acidic peat. The number of cells targeted by these probes was low (i.e., close to the detection limit) and comprised only 1.6 (±1.9) × 103 cells per g of wet peat. The application of probes with reported group specificity for type II MB of the Methylosinus/Methylocystis group, i.e., probes MA-221 and M-450, gave conflicting results for the number of type II MB in acidic peat. The probe MA-221 revealed only 1.8 (±0.8) × 104 cells per g of wet peat, while the use of probe M-450 led to the detection of 1.8 (±0.1) × 106 methanotroph cells g−1.

To clarify the reason for such a profound difference in cell counts, the target specificity of probes MA-221 and M-450 was compared using the probe match tool of the Ribosomal Database Project (21). The probe check revealed that M-450 possesses a very wide scope and perfectly matches almost all 16S rRNA sequences of Methylosinus and Methylocystis strains deposited in public databases. In contrast, the scope of MA-221 is more limited and includes mostly Methylosinus spp. and only some strains of Methylocystis. At least three known strains of Methylocystis, i.e., M. echinoides strain 2, “M. minimus ” strain 42 (10), and Methylocystis sp. strain LW5 (12), are not targeted by MA-221. The same is true for a large collection of Methylocystis strains isolated from diverse environments (P. Dunfield and J. Heyer, Abstr. P.08.039, 9th Int. Symp. Microb. Ecol., 2001). Thus, it can be assumed that some of the above-mentioned Methylocystis spp. or other hitherto uncharacterized Methylocystis strains account for most (about 99%) of the cells detected by probe M-450 in native peat. Based on the present data it cannot be concluded whether the Methylocystis population detected in acidic peat encompasses only one or a few different species and whether it represents acidophilic or just acid-tolerant organisms.

Interestingly, the colonization of Sphagnum bogs by Methylocystis-like populations has already been suggested previously based on the analysis of DNA extracted directly from peat (25, 26, 27). These studies revealed clusters of environmental 16S rDNA, pmoA, and mxaF sequences which grouped close to but were distinct from sequences of cultured Methylocystis strains. Our study provides additional evidence for this finding and data on their numerical abundance in acidic peat. Future investigations should address questions related to the taxonomic status and acidophilic/acid-tolerant nature of these Methylocystis-like populations.

In summary, we have demonstrated the applicability of a set of methanotroph-specific rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for the reliable enumeration of MB in a native peat sample. The total number of MB detected by FISH was 3.0 (±0.2) × 106 cells per g of peat (wet weight), comprising about 0.8% of total bacterial cells. The numerical abundance of MB determined by FISH is in good agreement with values (105 to 107 cells per g of wet peat) calculated by Sundh et al. (30) based on quantitative analysis of methanotroph-specific phospholipid fatty acids extracted directly from acidic peat. However, compared to the phospholipid approach, FISH has the clear advantage of direct cell counting. The indigenous methanotroph populations were represented mainly by type II MB, while type I MB accounted for less than 0.1% of detectable methanotroph cells. Type II MB were characterized by M. palustris and an uncharacterized Methylocystis population, which constituted approximately 40 and 60%, respectively, of the total MB detected by FISH. The methodological tool box described here for enumeration of MB in acidic peat bogs, including quantitative cell extraction and a set of group-specific rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes, will now allow the assessment of whether Methylocella palustris and Methylocystis spp. are widely distributed in Sphagnum bogs of the northern hemisphere and in other acidic oligotrophic habitats.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nicolai S. Panikov for providing us with a Sphagnum peat sample and highly valuable advice concerning cell extraction from peat. We also thank Gundula Eller, Stephan Stubner, and Peter Frenzel for helpful discussion about the in situ detection of MB and Peter Dunfield for providing information on 16S rDNA sequences for type II MB.

This research was supported in part by the Russian Fund of Basic Research, grants 99-04-48725 and 99-04-04035, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (436 RUS 113/543/0).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm E W, Oerther D B, Larsen N, Stahl D A, Raskin L. The oligonucleotide probe database. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3557–3559. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3557-3559.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becking J-H. Genus Beijerinckia. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1984. pp. 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodrossy L, Holmes E M, Holmes A J, Kovacs K L, Murrell J C. Analysis of 16S rRNA and methane monooxygenase gene sequences reveals a novel group of thermotolerant and thermophilic methanotrophs, Methylocaldum gen. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s002030050527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourne D G, Holmes A J, Iversen N, Murrell J C. Fluorescent oligonucleotide rDNA probes for specific detection of methane oxidising bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2000;31:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman J P, Sly L I, Stackebrandt E. The phylogenetic position of the family Methylococcaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:182–185. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-1-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman J P, McCammon S A, Skerratt J H. Methylosphaera hansonii gen. nov., sp. nov., a psychrophilic, group I methanotroph from Antarctic marine-salinity, meromictic lakes. Microbiology. 1997;143:1451–1459. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brusseau G A, Bulygina E S, Hanson R S. Phylogenetic analysis and development of probes for differentiating methylotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:626–636. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.626-636.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen H, Hansen M, Sørensen J. Counting and size classification of active soil bacteria by fluorescence in situ hybridization with an rRNA oligonucleotide probe. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1753–1761. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1753-1761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costello A, Lidstrom M E. Molecular characterization of functional and phylogenetic genes from natural populations of methanotrophs in lake sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5066–5074. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5066-5074.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dedysh S N, Panikov N S, Tiedje J M. Acidophilic methanotrophic communities from Sphagnum peat bogs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:922–929. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.922-929.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dedysh S N, Panikov N S, Liesack W, Groβkopf R, Zhou J, Tiedje J M. Isolation of acidophilic methane-oxidizing bacteria from northern peat wetlands. Science. 1998;282:281–284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedysh S N, Liesack W, Khmelenina V N, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A, Semrau J D, Bares A M, Panikov N S, Tiedje J M. Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp. nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bogs, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:955–969. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eller G, Stubner S, Frenzel P. Group-specific 16S rRNA targeted probes for the detection of type I and type II methanotrophs by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;198:91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs B M, Glöckner F O, Wulf J, Amann R. Unlabeled helper oligonucleotides increase the in situ accessibility to 16S rRNA of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3603–3607. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3603-3607.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs B M, Wallner G, Beisker W, Schwippl I, Ludwig W, Amann R. Flow cytometric analysis of the in situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA for fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4973–4982. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4973-4982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn D, Amann R I, Ludwig W, Akkermans A D L, Schleifer K-H. Detection of microorganisms in soil after in situ hybridization with rRNA-targeted, fluorescently labelled oligonucleotides. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:879–887. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-5-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes A J, Owens N J P, Murrell J C. Detection of novel marine methanotrophs using phylogenetic and functional gene probes after methane enrichment. Microbiology. 1995;141:1947–1955. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-8-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Parker C T, Jr, Garrity G M, Larsen N, Li B, Lilburn T G, McCaughey M J, Olsen G J, Overbeck R, Pramanik S, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M, Woese C R. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:171–173. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manz W, Amann R, Ludwig W, Wagner M, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic oligonucleotide probes for the major subclasses of Proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews E, Fung I. Methane emissions from natural wetlands: global distribution, area, and environmental characteristics of sources. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1987;1:61–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McConaughy B L, Laird C D, McCarthy B J. Nucleic acid reassociation in formamide. Biochemistry. 1969;8:3289–3295. doi: 10.1021/bi00836a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald I R, Hall G H, Pickup R W, Murrell J C. Methane oxidation potential and preliminary analysis of methanotrophs in blanket bog peat using molecular ecology techniques. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;21:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald I R, Murrell J C. The methanol dehydrogenase structural gene mxaF and its use as a functional gene probe for methanotrophs and methylotrophs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3218–3224. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3218-3224.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald I R, Murrell J C. The particulate methane monooxygenase gene pmoA and its use as a functional gene probe for methanotrophs. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murrell J C, McDonald I R, Bourne D G. Molecular methods for the study of methanotroph ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;27:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stahl D A, Amann R. Development and application of nucleic acid probes. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: Wiley and Sons; 1991. pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundh I, Borda P, Nilsson M, Svensson B H. Estimation of cell numbers of methanotrophic bacteria in boreal peatlands based on analysis of specific phospholipid fatty acids. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;18:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsien H C, Bratina B J, Tsuji K, Hanson R S. Use of oligonucleotide signature probes for identification of physiological groups of methylotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2858–2865. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2858-2865.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittenbury R, Phillips K C, Wilkinson T F. Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;61:205–218. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wise M G, McArthur J V, Shimkets L J. Methanotroph diversity in landfill soil: isolation of novel type I and type II methanotrophs whose presence was suggested by culture-independent 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4887–4897. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4887-4897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]