Abstract

Many modifications to the mammalian bauplan associated with the obligate aquatic lives of cetaceans—fusiform bodies, flukes, flippers, and blowholes—are evident at a glance. But among the most strikingly unusual and divergent features of modern cetacean anatomy are the arrangements of their cranial bones: (1) bones that are situated at opposite ends of the skull in other mammals are positioned close together, their proximity resulting from (2) these bones extensively overlapping the bones that ordinarily would separate them. The term “telescoping” is commonly used to describe the odd anatomy of modern cetacean skulls, yet its usage and the particular skull features to which it refers vary widely. Placing the term in historical and biological context, this review offers an explicit definition of telescoping that includes the two criteria enumerated above. Defining telescoping in this way draws attention to many specific biological questions that are raised by the unusual anatomy of cetacean skulls; highlights the central role of sutures as the locus for changes in the sizes, shapes, mechanical properties, and connectivity of cranial bones; and emphasizes the importance of sutures in skull development and evolution. The unusual arrangements of cranial bones and sutures referred to as telescoping are not easily explained by what is known about cranial development in more conventional mammals. Discovering the evolutionary-developmental processes that produce the extensive overlap characteristic of cetacean telescoping will give insights into both cetacean evolution and the “rules” that more generally govern mammalian skull function, development, and evolution.

Keywords: telescoping, skull, cranial sutures, Cetacea, evo-devo

“…the process which the skulls of all known cetaceans except the zeuglodonts [basilosaurids] have undergone is a highly developed system of ‘telescoping’; that is, the portion of the skull lying behind the rostrum has been shortened, not so much by a reduction of the anteroposterior diameter of individual bones (except the parietal), as by a slipping of one bone over another or by the interdigitating of some of the elements. Alteration of contact-relationship is here not the exception but the rule” (Miller, 1923, p. 2).

Crown cetaceans (including living whales, dolphins, and porpoises) have skulls with morphologies that represent a significant break from the structural theme that underlies most mammalian skull diversity. In the skulls of most mammals, homologous bones articulate in a relatively conserved pattern, fitting together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle: changes in the shape and proportions of one skull bone often involve reciprocal changes in the sizes and shapes of adjacent bones (Pearson and Davin, 1924; Pearson and Woo, 1935; de Beer, 1937; Roth, 1991). While maintaining this structural theme, mammals have evolved diverse skull sizes and shapes, feeding habits, and sensory adaptations (de Beer, 1937; Moore, 1981; Novacek, 1993). Yet, whereas in other mammals, bones of the calvarium fit together to form a single bony sheet, in cetaceans, they may overlap or be overlapped extensively. (See Table 1, Part I, for a description using more specific anatomical terms.) In some species, bones overlap to a degree so extreme that they nearly or completely hide underlying bones from external view of the skull.

Table 1.

Description and definition of telescoping as the term is used in this paper.

|

I. A

synoptic description, in anatomical terms, of the telescoped condition as it is manifest in modern cetaceans: (a) In modern odontocetes (the cetacean suborder comprising toothed whales such as dolphins and sperm whales) the premaxilla and maxilla extend posteriad and cover the frontal; (b) In mysticetes (the other modern suborder of cetaceans, comprising baleen whales) the occipital overlies the parietals, which may in turn overlie the frontals anteriad (and in some species the premaxilla and maxilla also overlie the frontals); (c) as Miller (1923) and Kellogg (1928a,b) described in detail, the positional relationships between adjacent and intervening bones differ considerably among taxa —the net effect in all cases is that the premaxilla and maxilla contact or come close to contacting the interparietal and occipital. |

|

|

|

II.

A definition, in most general terms, of telescoping: the combination of (i) extensive bone overlapand (ii) extreme proximity of anterior and posterior cranial elements that is observed in the skulls of modern cetaceans. a restatement of the definition, incorporating relevant anatomical terms: (ii) maxillo-occipital proximity or [an equivalent statement, referring to a complementary set of bones] (ii)longitudinalshortening of those portions of the frontal and parietal bones that are visible from the dorsal surface of the skull as a result of (i) extensive bone overlap. |

This structural divergence of cetacean skulls from those of typical mammals has been referred to as “telescoping” (Fig. 1) (Miller, 1923). Changes in bone contact described as telescoping mark an important innovation in cetacean evolutionary history. While these changes have influenced the form of the skull and the relative positions of particular bones, they have also entailed profound modification of the sutures between the bones (Miller, 1923) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Telescoping as a metaphor for two aspects of cetacean skull morphology. (A) An old-fashioned collapsible telescope (spyglass). Collapsing the telescope decreases its length as the overlap of intervening elements increases. (B) A mammal skull that adheres to the conserved structure and pattern of articulation observed in most mammals (Canis familiaris, NCSM 17631). Arrows highlight the distances between the sutural boundaries delineating the maxilla, frontal, and interparietal + occipital. (C) A dolphin skull (Tursiops truncatus, NCSM 8293). Arrows show the shortened distance between the maxilla and occipital on the dorsal surface of the dolphin skull relative to (B). Only a small portion of the frontal is observed externally. (D) A disarticulated dolphin skull (modified from Kellogg, 1928a). With the maxilla and premaxilla removed, the full extent of the frontal is observed. Extensive overlap of the maxilla over the frontal nearly hides the frontal from external view, resulting in the shortened distance in (C). Maxilla (blue), premaxilla (blue), frontal (green), interparietal + occipital (orange; fused), nasal (yellow).

Fig. 2.

Examples of articular surfaces that underlie extensive bone overlap in a disarticulated fetal balaenopterid mysticete (LACM 84179). (A) Left frontal, lateral view. (B) Left parietal, lateral view. (C) Left frontal, dorsal view. (D) Left and right parietals, dorsal view. Articular surfaces that underlie extensive overlap are outlined, and the bone articulating with that surface is noted in parentheses. Skull diagrams in the upper right corners indicate the photographed bone with color. White arrows in (C and D) show the perspective from which the bones in dorsal view were photographed. (Note that most of the dorsal surface of the parietals underlies the occipitals and is not visible from a dorsal view of the skull, therefore the position of the parietals is shown with hashmarks in the dorsal-view diagram in D.)

The existence of telescoped skull morphologies in cetaceans raises fundamental questions about mammalian skull anatomy, function, and development. For instance, what evolutionary changes to developmental processes allowed cetacean cranial bones to overlap to so great a degree and to diverge so radically from those of typical mammals? What are the functional consequences of extensive overlap between bones—that is, how does it affect sensory, feeding, and breathing functions in which the skull participates—and how, in the regions of overlap specifically, does the functioning differ from the functions of a typical suture? Cetacean skulls provide an intriguing system for studying divergent extremes of mammalian morphology and the developmental mechanisms that underlie them (Thewissen and Bajpai, 2001).

In the nearly 100 years since Miller (1923) first described these derived anatomical conditions of cetacean skulls and applied the term “telescoping” to them, the challenge of developing a fully integrative account of the functional, developmental, and evolutionary bases of cetacean skull telescoping remains unmet. Today, the authoritative references on telescoping continue to be the detailed, foundational monographs of Miller (1923) and Kellogg (1928a, 1928b). However, concurrent with scientific advances on several fronts and while continuing to cite Miller, descriptions and implicit definitions of the telescoped condition have diverged from what Miller’s original account encompassed (Table 2). Divergent applications of the term “telescoping” can hinder unified progress toward understanding its biology.

Table 2.

Select examples of the usage of “telescoping” (1997-present).

| “…a pattern of skull bone position referred to as ‘telescoping’…” | (Armfield et al., 2011) |

| “…cetacean skulls became more telescoped as the nasal openings migrated dorsally (Miller 1923).” | (Bejder & Hall, 2002) |

| “…crown cetaceans differ from stem taxa (archaeocetes) in having a ‘telescoped’ skull in which the facial bones, particularly the premaxilla and maxilla extend posteriorly to form most of the skull roof producing an elongate rostrum (beak) and dorsal nasal openings (Miller, 1923).” | (Berta et al., 2014) |

| “… the fossil record documents movement of the external bony nares from the rostral to the caudo-dorsal region of the skull, and the bones of the dorsal aspect of the skull exhibit overlapping layers (a condition known as ‘telescoping’)…” | (Buono et al., 2015) |

| “The skull of dolphins (and cetaceans in general) underwent a process of elongation, called telescopy (Miller 1923).” | (Cozzi et al., 2016) |

| “Miller (1923) coined the term ‘telescoping’ to describe the restructuring process that pushed the nasal passages posteriorly in the cetacean skull. In dolphins, the bones of the face slide over more posterior bony elements and accommodate the enlarged soft tissue mass of the forehead atop the elongate rostrum.” | (Cranford et al., 2014) |

| “Cranial telescoping plays a prominent role in cetacean evolution and involves the relocation of the external nares from an anterior position at the front of the rostrum to a progressively more posterior position above or behind the orbits. One measure of the degree of telescoping is the location of the nasal frontal suture relative to the supraorbital process of the frontal.” | (Demere & Berta, 2008) |

| “The anterior part of the skull was laterally expanded, while the area around the brain was compressed. As would be expected from the telescoping of the odontocete skull (Miller 1923), the landmarks in the facial region were displaced caudally. The skull vertex (occipital crest) showed rostral movement, also complying with the supraoccipital ‘telescoping’ over the parietal and frontal bones during cetacean ontogeny.” | (Galatius & Gol’din, 2011) |

| “…telescoping is the evolutionary transformation where bones that previously contacted along vertical or near vertical sutures now contact along nearly horizontal sutures. To obtain this sutural reorientation, one bone ‘slid’ over the other, similar to the way the nested cylinders of a mariner’s telescope slide over each other when the scope is collapsed.” | (Gatesy et al., 2013) |

| “Eight of these characters (e.g., characters 74, 77, 80) relate to telescoping of the cetacean skull, which involves the posterior movement of the nasal passages and cranial bones in cetacean evolution (Miller, 1923).” | (Geisler & Sanders, 2003) |

| “The majority of these characters are associated with ‘telescoping;’ a term coined by Miller (1923) to describe the evolutionary revamping of the cranial vault (Fig. 35.2) in which the maxillary bones of the upper jaw expanded back to the vertex of the skull and covered the reduced frontal bones.” | (Ketten, 1992) |

| “…underwent a pronounced reorganization of their facial bones--a process commonly known as telescoping--to facilitate breathing.” “Most of the rostral bones of neocetes are affected by telescoping (Miller, 1923), which is the stacking of several bones caused mainly by the backward displacement of the external narial opening toward the top of the skull” |

(Marx et al., 2016) |

| “Telescoping in odontocetes is defined by the positioning of the maxilla and premaxilla in the skull (Miller, 1923; Kellogg, 1928a, 1928b). The premaxilla and the ascending process of the maxilla override the frontal and the parietal bones pushing dorsally and caudally (Miller, 1923; Oelschlager, 1990; Comtesse-Weidner, 2007). This dorsal movement of anterior skeletal elements alters the location of the sutures between specific bones (Miller, 1923). The premaxilla touches the supraoccipital bone and the nasal, premaxilla, maxilla, parietal, and frontal bones are all in close contact (Miller, 1923). The result of telescoping in odontocetes is the reduction in the intertemporal region of the skull and it has been suggested that this facilitates anatomical adaptations for echolocation (Kellogg, 1928a; Oelschlager, 1990). Telescoping results in altering the shape of the anterior cranium and flattening of the cranial bones (Reidenberg and Laitman, 2008), |

(Moran et al., 2011) |

| “Telescoping of their skulls was a complex phenomenon involving contrasting changes in the facial and cranial regions. The rostrum elongates and the nasal bones and bony nares are repositioned to the top of the skull as the nasopharyngeal chamber is profoundly reorganized to accommodate breathing (Miller, 1923)” | (Racicot & Rowe, 2014) |

| “The cetacean skull is described as having ‘telescoped’ through evolution, with facial and vault bones flattening and overlapping each other (Miller, 1923; Kellogg, 1928; Rommel, 1990; Rommel et al., 2002). Repositioning of the cetacean anterior nasal apertures is associated with the rostral (e.g., maxilla and premaxilla) and caudal (e.g., occipital) cranial bones approximating each other near the dorsum of the skull. Evolutionarily, in the process of telescoping, the cetacean maxillary and frontal bones have become so flattened that they no longer contain the hollow chambers of the maxillary and frontal paranasal sinuses of archaeocetes.” | (Reidenberg & Laitman, 2008) |

The time is opportune to revisit the meaning—both terminological and biological—of cetacean telescoping. During the last century, our understanding of general aspects of mammalian skull evolution, development, and biomechanics has advanced considerably (e.g., Jaslow, 1990; Smith, 1996; Goswami, 2006; Marroig et al., 2009; Porto et al., 2009; Koyabu et al., 2012; Cardini and Polly, 2013). Yet even today, telescoping of cetacean skulls remains poorly explained. Several advances in cetacean biology provide new context for understanding the evolution of telescoped morphologies that was unavailable to Miller (1923) and Kellogg (1928a, 1928b), including recognition that cetaceans are nested within terrestrial artiodactyls (Gingerich, 2001; Thewissen et al., 2001). A robust and growing fossil record of forms that preceded the telescoped skulls of modern cetaceans (and that may be intermediate between them and their un-telescoped ancestors) permits evolutionary processes to be inferred and hypotheses to be tested (e.g., Deméré et al., 2008; Hampe and Baszio, 2010; Velez-Juarbe et al., 2015; Churchill et al., 2016; Marx and Fordyce, 2016; Geisler et al., 2017; Peredo et al., 2017; Pyenson, 2017; Churchill et al., 2018). New technology, especially noninvasive 3D imaging, is making rare and fragile specimens more accessible for research and allows telescoped morphologies—especially those of fetal specimens—to be studied for the first time in all dimensions (e.g., Roston et al., 2015, 2016;, 2017). These new data, obtained from new sources and placed in new interpretive contexts, promise to clarify the evolutionary processes responsible for cetacean skull morphology and to situate it meaningfully within a broader understanding of mammalian skull diversity.

Our goals in this review are twofold. In the next section, we will examine “telescoping” as a term, both its limitations and the rationale for maintaining it. We then provide an explicit definition of telescoping that clarifies and elaborates upon Miller’s (1923) account. Lack of such a definition has promoted confusion in biological interpretation of, and communication about, telescoping and its associated phenomena (cf. Cartmill, 1982).

Our second goal, addressed subsequently in two major sections of the article, is to clarify the relevance of cetacean telescoping for understanding skull biology more generally. To this end, while recommending an interdisciplinary approach to understanding the collection of phenomena that constitute telescoping and its underlying biology, we review the current state of knowledge of the evolutionary and developmental origins of telescoping, discuss implications, and outline some of the biological questions raised by cetacean telescoping—and particularly, the cranial sutures it involves—for current research in multiple fields of biology. Our overarching goal is to provide a point of departure for continuing discussion and further research.

TERMINOLOGY: WHAT IS TELESCOPING?

History of the Term

Although the morphologies to which telescoping refers had been described even earlier (e.g., Carte and Macalister, 1868; Abel, 1902), the metaphor of telescoping can be traced back a century. Winge (1918, 1921) included the character “sammenskudt” (telescoped) in his taxonomic descriptions of cetaceans but did not define what he meant by it. Miller (1923) adopted the term in the title of his monograph, described in detail what he considered components of the telescoped condition in extant cetacean families, and compared them to similar features in other mammals. As stated in the epigraph to this article (above), Miller noted three important attributes of telescoping: (1) the degree of overlap between skull bones extends far beyond that in other mammal skulls (Figs. 2 and 3), (2) this great overlap causes nonadjacent bones to come into proximity with or directly contact each other, and (3) the net effect of approximation of nonadjacent anterior and posterior elements is the perceived “shortening of the skull” posterior to the orbits (Fig. 4A–E). In associating skull “shortening” with bone overlap, Miller’s interpretation differs slightly from Winge’s, who considered “braincase shortened” and “braincase telescoped” as separate taxonomic characters (Winge, 1918, 1921).

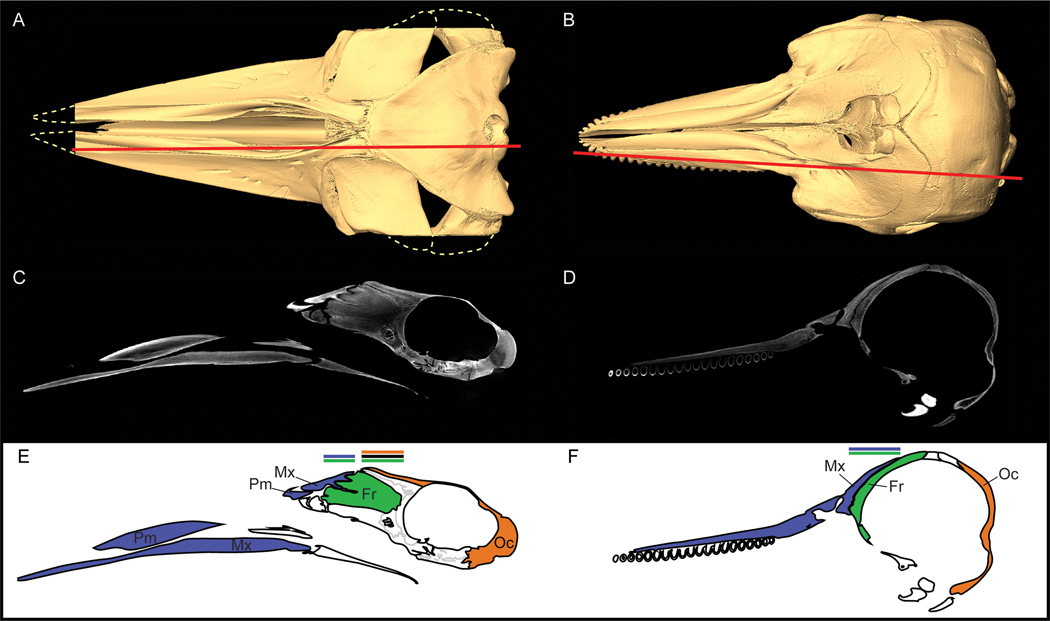

Fig. 3.

CT scans show extensive bone overlap of an immature minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata, a mysticete; USNM 571236) (left) and of a juvenile dolphin (T. truncatus, an odontocete; WAM 704) (right). (A, B) 3D surface reconstructions in dorsal view; red line indicates the plane of the parasagittal slice in C and D. (C, D) Parasagittal CT slices showing broad maxilla-frontal overlap. (E, F) Color-coded diagrams drawn from CT slices. Regions of extensive overlap are indicated with correspondingly colored horizontal lines.

Fig. 4.

(A–E) Illustrations of skull vertices in dorsal view for select taxa. Note the proximity of the maxillae and premaxillae to the supraoccipital (+interparietal) in the four cetacean species (B–E) compared to the outgroup (A) (Hippopotamus). (F–H) Schematics comparing dorsal views of the skulls of (F) a “typical” mammal with the telescoped skulls of (G) an archetypal odontocete and (H) archetypal mysticete. The topological relationships illustrated are characteristic of the odontocete and mysticete bauplans, but anatomical details such as the relative sizes and shapes of bones may vary by species. Regions of overlap described as telescoped are indicated with parallel diagonal lines in the color of the underlying bone. (A) Hippopotamus amphibius (AMNH 90230). (B) Tursiops truncatus (Odontoceti: Delphinidae) (based on/modified from Kellogg, 1928a). (C) Balaenoptera physalus (USNM 16039) (Mysticeti: Balaenopteridae) (modified from Miller, 1923). (D) Ziphius cavirostris (NCSM 12806) (Odontoceti: Ziphiidae). (E) Eubalaena glacialis (USNM 23077) (Mysticeti: Balaenidae) (modified from Miller, 1923). (F) A generalized “typical” mammalian skull. (G) A generalized odontocete bauplan, modeled after a delphinid. (No attempt has been made to represent the bilateral asymmetry characteristic of odontocete skulls.) (H) A generalized mysticete bauplan, modeled after a balaenopterid.

On the basis of whether bones at the back or at the front override the intervening ones, Miller (1923) described two distinct bauplans of telescoping in the two extant cetacean suborders: maxillary dominance in odontocetes (toothed whales; e.g., porpoises, dolphins) and supraoccipital dominance in mysticetes (baleen whales) (Table 1, Part I; Figs. 4F–H and 5). (These were described, respectively, as retrograde and prograde telescoping in Churchill et al., 2018.) Contrary to this dichotomy, however, Miller also detailed examples from both suborders in which both anterior and posterior elements contribute to telescoping (e.g., ziphiids and physeteroids in the Odontoceti and balaenopterids in Mysticeti). The ascending process of the maxilla may overlie portions of the frontal as it extends posteriorly past the nasal bones (Geisler and Sanders, 2003) and may therefore contribute to telescoping in both odontocetes and mysticetes. Although we emphasize the changes to bones in the dorsal skull roof, other regions of the skull may also be involved (e.g., pterygoid, alisphenoid, and palatine; Miller, 1923, pp. 2, 31).

Fig. 5.

Phylogeny of taxa discussed in this article (based on Gatesy et al., 2013). The origins of crown cetaceans (Neoceti) (star), odontocetestyle telescoping (blue circle; O), and mysticete-style telescoping (orange circle; M) are indicated. Illustrations (also in Fig. 4) on the right show a representative skull vertex for extant families.

Although extensive overlap, by its nature, increases the proximity of nonadjacent elements, these two features can vary somewhat independently if other changes also occur. Increased proximity of nonadjacent anterior and posterior elements can be accomplished without bone overlap simply through reduction of the sizes of intervening bones (frontals and parietals). Conversely, overlap can be achieved without increasing proximity of nonadjacent elements if the underlying bones are concurrently expanded. In some cetaceans, bone overlap is accompanied by a change in orientation (forward tilt) of the supraoccipital and with anteriad displacement of the nuchal crest toward the skull vertex (Figs. 3A and 4A–E). Given the geometry of spatial connectivity within the skull, a change in the position, orientation, or contacts of a given set of bones almost inevitably has consequences for contiguous regions.

In the years following introduction of the term, “telescoping” has been variously used to refer not just to features mentioned by Miller (1923) but also to changes that accompanied the evolution of these features. For example, it has been used not simply to refer to extensive bone overlap and shortening of the distance between typically anterior and posterior cranial elements but also to the evolutionary “migration” of the nares to become a blowhole (alternatively described as repositioning and reorientation of the nasal passages) or the anteriad elongation of the rostrum. In its varied usages, the term “telescoping” purportedly involves facial and/or cranial regions, motion, displacement, stacking, and flattening of bones as well as sutural reorientation (Table 2). The term has also been used to imply cause and effect: certain changes required or produced others (perhaps implying that selection acting on one part drove passive change in another). “Telescoping” occurs frequently with words like “associated” to acknowledge that complex geometry and geometric and functional interdependency require changes to be coordinated. To complicate issues further, in some instances, telescoping appears to be equated with bone overlap alone, in one or another region of the cetacean skull. Most authors who have used the term have ultimately left the definition of the term itself unstated.

“Telescoping” is an evocative metaphor, and it is evident from its continuing and widespread use in scientific literature that a word is needed that succinctly captures what is unusual about the anatomy of all modern cetacean crania. Miller’s (1923) dissemination of the term has helped to maintain his richly detailed monograph in citations and bibliographies into the 21st century. Yet, as noted above, the metaphor has spread without the term having been clearly defined and, as a result, it is unclear to what extent different authors are referring to the same phenomena. The term “telescoping” has from its inception referred to several distinct anatomical conditions (Table 1, Part I) and has therefore also been described as an “ambiguous” term requiring qualification (Fordyce and de Muizon, 2001).

As a solution to these difficulties, and because of the historical significance carried by the term, we will propose here a definition of telescoping that meets several criteria: the definition refers to peculiar features of skull morphology shared by all modern cetaceans; it conforms to Miller’s original interpretation of this term, the metaphor of a collapsible spyglass; however, it describes the condition in a somewhat more concrete way. The term “telescoping” names a particular category of phenomena, and if used more consistently, it has potential for unifying a field of study around it.

Examining and refining the definition of telescoping serves as a starting point for exploring some of the questions this unusual combination of features presents for modern biologists and for enhancing our understanding more generally of mammalian skull biology.

A Clarified Definition

Throughout this article, and unless otherwise noted, we will use telescoped (adjective) and telescoping (noun) to refer to skulls that have the combination of (i) extensive bone overlap and (ii) extreme proximity of anterior and posterior cranial elements that is observed in modern cetaceans (Table 1, Part II).

In contrast to the many complex modern usages (Table 2), this definition is both specific enough to allow the advancement of evolutionary, developmental, and functional hypotheses and sufficiently general to refer to skull morphologies of all crown cetaceans (neocetes) despite anatomical differences. However, telescoping is an imperfect metaphor because, unlike the collapsing (or shortening) of a spyglass, the internal dimensions of the cetacean cranial vault (or, “portion of the skull lying behind the rostrum”) may not be reduced by telescoping; in contrast to the image that Miller’s use (see epigraph above) of the word “shortening” may conjure, many cetaceans have enlarged brains (Jerison, 1973; Marino et al., 2004; Marino, 2009; Oelschläger and Oelschläger, 2009).

Henceforth, we will refer to the approximation of these elements as “maxillo-occipital proximity” or “reduction in maxillo-occipital distance.” Romer (1966) succinctly captured the geometry of this anteroposterior approximation, stating that, “Osteologically there is no top to the skull; it is all front and back” (Romer, 1966). In other words, externally, the dorsum of the skull in cetaceans is formed by the bones that traditionally form the front (maxilla and premaxilla) and back (interparietal and occipital) of the skull in other mammals (Fig. 4). The extreme situation, in which the intervening frontal and parietal bones are overridden and completely obscured on the exterior dorsal surface (vertex), is found only in some members of some species (e.g., Balaenoptera musculus), whereas incomplete frontal and parietal obscurity is found in others (e.g., Balaenoptera physalus) (Miller, 1923). An alternative phrasing for telescoping would be (ii) longitudinal shortening of those portions of the frontal and parietal bones that are visible from the dorsal surface of the skull as a result of (i) extensive bone overlap (Table 1, Part II).

The presence of a blowhole (dorsally situated nares) in all modern cetaceans has led many authors to include the external nares among the anterior features that have moved posteriad in the process of telescoping (Romer, 1966; Geisler et al., 2011; Berta et al., 2015). However, shifting of the nares is not morphogenetically required for extensive overlap of the frontal by maxillary and/or occipital bones to occur (nor does it feature in the analogy with a collapsible telescope). Including it in the definition of cetacean telescoping therefore incorporates assumptions about a coupling between narial position and bone overlap that could hamper hypothesis-testing about any developmental, functional, and evolutionary linkages between blowhole evolution and other osteological features.

Phrasing like “extensive” overlap, and “shortening” or “extreme proximity” is explicitly qualitative and implicitly calls for quantification. Yet, we refrain here from defining criteria or indices for measuring degrees of telescoping, and this is deliberate. There is little if any controversy about all modern cetaceans qualifying as “telescoped”: the magnitude of overlap and of the reduction in maxillo-occipital distance they exhibit exceeds that of other mammals to a degree that their skulls appear qualitatively different (Figs. 3 and 4). Whereas measures of degree of overlap or separation of particular bones may be useful for comparisons among modern cetaceans and between fossil and modern forms, we believe that such metrics should be maintained separate from the definition of telescoping so that morphological diversity in particular anatomical regions can be specifically characterized. Thus, we prefer to leave construction and adaptation of such indices to individual (or groups of) scientists for particular comparative projects (Churchill et al., 2018). We also reserve usage of the term “telescoping” for the attribute in modern cetaceans and not for the evolutionary or developmental processes giving rise to it. These processes and intermediate states are best described in specific anatomical terms.

Under the definition proposed here, all neocete skulls qualify as telescoped, but as noted above (and as is widely recognized), telescoping in odontocetes and mysticetes encompasses modifications to different regions of the skull (see Table 1, Part I; Fig. 4F–H; section on homology below) (Winge, 1918, 1921; Miller, 1923; Berta et al., 2015; Marx et al., 2016). In odontocetes, the anterior elements (maxilla, premaxilla) broadly overlap the frontal posteriad. In mysticetes, accompanying some overlap of or interdigitation with the frontal by maxilla, a posterior element (occipital) overlaps the parietal anteriad (Figs. 3 and 4). Moreover, the bones involved in the two groups have different developmental origins: the maxilla and premaxilla are neural crest-derived and form through intramembranous ossification, whereas the occipital is mesoderm-derived and forms through endochondral (cartilage precursor) ossification (Morriss-Kay, 2001; Piekarski et al., 2014). The sutures in the facial and neurocranial regions of the skull also use somewhat different developmental mechanisms (Pritchard et al., 1956), yet both suture types have evolved broad overlap in cetaceans. Telescoped morphologies in each cetacean family have their own nuances and additional morphological details, varying, for example, in the relative contributions and extent of maxillary and/or supraoccipital overlap. These nuances are described in Miller (1923), as well as Kellogg (1928a, 1928b).

To resolve some of the terminological problems these differences raise, Mead and Fordyce (2009) separated telescoping into four “styles” by distinguishing the occurrence of both “facial” and “supraoccipital” telescoping in both odontocetes and mysticetes. But even with this subdivision, the considerable anatomical diversity represented within each of these categories suggests that clarity is best served by specifying for individual cases where in the skull overlap occurs and how closely anterior and posterior elements are brought together.

Because any metaphor is imprecise, and especially in the absence of an explicit definition and consistent usage, the term “telescoping” has led to disagreements about what parts of the skull it involves and therefore how to interpret intermediate states, generating discrepancies in interpretations of where anatomically and when telescoped morphologies originated in evolution or development. To curtail miscommunication, specific aspects of telescoping are best described with more precise anatomical or morphological vocabulary. It becomes especially important to use precise anatomical language, and to avoid the metaphor, when one delineates characters and defines character states for phylogenetic analyses. The morphological states telescoping encompasses are both disparate and, in the two modern subclades of Cetacea, distinct (with the possible exception of one component, the ascending process of the maxilla; see below). Telescoping is therefore best viewed not as a character, but as a global, structural attribute of a skull.

In recognition of both the utility and the enduring popularity of the term, we have offered here an explicit definition and advocate its usage in the broad sense introduced by Miller (1923) to describe, in their many manifestations in modern cetaceans, a combination of traits: extensive cranial bone overlap and a relative reduction, longitudinally, in the maxillo-occipital distance. Although one term is no substitute for a precise description of the anatomy of particular manifestations of the condition, or of particular aspects under investigation, reserving the use of “telescoping” for this combination of features (Table 1, Part II) can direct attention to questions provoked by the co-occurrence of these traits.

BIOLOGY OF TELESCOPING: AN OVERVIEW

What processes led to the evolution and development of these two traits—extensive bone overlap and relative shortening of the longitudinal distance between particular anterior and posterior elements—that are observed in extant cetacean skulls? And to what degree was telescoping a feature of the ancestor of crown cetaceans?

The Fossil Record

Although it describes several disparate morphologies, telescoping has been considered one of the defining features that separates neocetes (crown cetaceans) from archaeocetes (stem cetaceans) (e.g., Barnes, 1990; Berta et al., 2014). The evolutionary origins of telescoping have been obscure because, until fairly recently, few early neocete fossils had been described that could shed light on evolutionary processes that led to the telescoped skull morphologies of modern cetaceans. In his monograph, Miller (1923) included only the mysticete fossil Cetotherium and three stem odontocete fossils: Archaeodelphis, Agorophius, and Xenorophus. A rise in formal descriptions of early neocete fossils (Uhen, 2010) and reevaluation of previously described ones (e.g., Fitzgerald, 2010) has made the origin of Neoceti from archaeocetes a major focus in recent years and has re-opened investigation into possible evolutionary processes that led to modern telescoped skull morphologies.

The fossil record of the earliest neocetes is still relatively sparse, but divergence estimates based on fossil-calibrated molecular clocks and corroborated by other fossil evidence suggest that Neoceti arose in the late Eocene approximately ~36 Mya (McGowen et al., 2009; Geisler et al., 2011; Gatesy et al., 2013). Phylogenetic analyses that have combined molecular, morphological, and paleontological data (Geisler et al., 2011; Gatesy et al., 2013) have placed all known early neocete fossils as stem members of either the mysticete or odontocete clades (Uhen, 2010; Lambert et al., 2017). Crown mysticetes and crown odontocetes likely arose in the middle to late Oligocene (McGowen et al., 2009; Geisler et al., 2011; Marx and Fordyce, 2015).

Basilosaurids and archaeocetes more generally, which lived in the Eocene and persisted into the Oligocene, have been described as possessing “no trace” of the telescoped state (Miller, 1923; Kellogg, 1928a; Romer, 1966). That said, it is conceivable, and even likely, that some specific anatomical features that contribute to telescoping, such as overlap by and posteriad extension of the ascending process of the maxilla, may have arisen prior to the origin of Neoceti. For instance, the ascending process of the maxilla overlies a portion of the frontal in Zygorhiza kochii (Kellogg, 1936). Likewise, in broken Dorudon atrox skulls, parallel grooves on the anterior frontal suggest a convoluted overlapping suture between it and the now missing maxilla (see Fahlke, 2012). However, bone overlap between the maxilla and frontal, where present, is not expansive, and the maxillo-occipital distance is not strikingly reduced. Other mammal skulls also possess bone overlap at the maxillo-frontal suture while lacking a reduced maxillo-occipital distance (e.g., fox; Miller, 1923, Pl. 1 Fig. 1).

To date, only two neocete fossils have been described from the late Eocene, Llanocetus denticrenatus and Mystacodon selenensis, and both have been classified as stem mysticetes (Mitchell, 1989; Lambert et al., 2017; Fordyce and Marx, 2018). Both Mystacodon, which is described as the oldest known neocete (Lambert et al., 2017), and Llanocetus, whose skull was described recently (Fordyce and Marx, 2018), have an ascending process of the maxilla that overlies the frontal and a supraoccipital bone that is fairly vertical, but tilted slightly anteriad. The nuchal crest, at the anterior edge of the occipital, is in the posterior portion of the skull. As a result, the frontals and parietals in these fossils are broadly exposed dorsally and maxillo-occipital distance is not considerably decreased from the ancestral condition (Lambert et al., 2017; Fordyce and Marx, 2018).

Like these two Eocene mysticetes, Coronodon havensteini, a mysticete from the early Oligocene, had maxilla-frontal overlap and interlocking that resembled many other mysticetes, but its supraoccipital shield was only slightly tilted anteriad. In the late Oligocene, many mysticete fossils possessed a maxilla interlocked with the frontal such that the ascending process of the maxilla extends over the frontal dorsally, and as viewed from the lateral aspect, the infraorbital process of the maxilla extends ventral to it (the frontal) (e.g., Aetiocetidae: Emlong, 1966; Deméré and Berta, 2008; Marx et al., 2015; Mammalodontidae: Fitzgerald, 2006, 2010; Eomysticetidae: Sanders and Barnes, 2002b; Boessenecker and Fordyce, 2015). In these stem mysticetes (e.g., Sanders and Barnes, 2002a; Marx et al., 2015), the supraoccipital tilted anteriad dorsally and the longitudinal position of the nuchal crest varied. Despite this tilt of the supraoccipital, the frontals and parietals were both broadly visible on the dorsal skull.

The earliest currently known odontocete fossils (e.g., Simocetus, ~32 Mya, Fordyce, 2002; Marx et al., 2016) date to the early Oligocene. Their appearance relatively soon after molecular-clock estimates of odontocete-mysticete divergence (McGowen et al., 2009) suggests that some anatomical characteristics that are distinctive of telescoping in odontocetes, the broadened maxillo-frontal overlap in particular, arose relatively rapidly. Collectively, Oligocene odontocete fossils display bone overlap and maxillo-occipital proximity to varying degrees and in various combinations. In the skulls of Archaeodelphis patrius and Simocetus rayi, for example, large areas of the frontal bone remain uncovered by the maxilla laterally, but in other species, such as Waipatia maerewhenua, the maxilla completely, or nearly completely, covers the supraorbital process of the frontal (Allen, 1921; Fordyce, 1994; Fordyce, 2002). During the Oligocene, the identities of the bones that contributed to overlap also varied: in xenorophid skulls the lacrimal, laterally, and premaxilla, medially, overlap the frontal alongside the maxilla (Kellogg, 1928a; Uhen, 2008; Sanders and Geisler, 2015). Despite varying but high degrees of bone overlap over the frontal, most Oligocene odontocetes had substantial portions of the frontal and parietal bones exposed dorsally and largely lacked the longitudinal reduction of maxillo-occipital distance observed in modern odontocetes.

The growing record of fossil morphologies suggests a complex, mosaic evolution of the traits (such as maxillo-frontal overlap, occipito-parietal overlap, obliquely oriented supraoccipital, etc.) that contribute to the modern telescoped condition. As described above, some components, such as posteriad extension of the ascending process of the maxilla, may have arisen in neocete ancestors (archaeocetes) (e.g., Geisler and Sanders, 2003). Variability in the expansiveness of bone overlap and degree of maxillo-occipital proximity in late Oligocene odontocetes shows that diverse bauplans were present from relatively early on and that telescoped skull morphologies were attained in various ways. All Oligocene fossils described to date fall phylogenetically outside the modern crown groups Odontoceti and Mysticeti, suggesting that there was an early phase of morphological experimentation that preceded radiation within each of these crown groups (Marx and Fordyce, 2015).

Because “telescoping” was coined to refer to the overall appearance of extant cetacean skulls, the term becomes difficult to apply to mosaic or intermediate states that may be evident as fossils continue to be discovered. Setting thresholds for degrees of overlap and maxilla-occipital proximity for a skull to qualify as telescoped is a subjective decision, but we follow Miller (1923) in requiring both features to be present. Ultimately, we would argue, it matters little whether a particular fossil crosses a threshold to qualify as “telescoped” if an investigator can make clear specifically what traits it possesses and shares or does not share with other specimens. Where bony overlap can be observed directly in fossils, explicit descriptions of this and other features, referring to specific bones and their spatial relationships (Geisler and Sanders, 2003; Uhen, 2008) provide the most clarity for recognizing what, if any, correlations have existed between extensive overlap and other features of the skull.

Fossils have much to tell us about how the modern states of telescoping arose and what combinations of traits, even if they do not exist today, have been possible. What implications do the occupied regions of morphospace, past and present, have for hypotheses about the functional roles of telescoping? Have cetaceans broken a mammalian evolutionary-developmental constraint that has led to a radiation of novel skull morphologies into previously unoccupied regions of morphospace? And what, for example, can be learned about functional and developmental constraints (or their absence) from the evolutionary reversal or “loss” of telescoping that is inferred to have taken place in Odobenocetops (de Muizon and Domning, 2002)? Which combinations of the array of morphological features that contribute to the telescoped condition today have changed together, and which could be considered independently evolving characters? Although defining telescoping explicitly in terms of its two components provides greater clarity in communication for addressing these questions, explicit, anatomically specific characterization of fossils is essential. Such detailed description will continue to contribute significantly to the generation and testing of hypotheses about the basic biology of the combination of phenomena that are encompassed by this term that describes skulls of all modern cetaceans.

Hypotheses of Functional Origins

Given that the extraordinarily derived condition known as telescoping exists in both sister groups that constitute crown Cetacea, but with significant differences between them in morphological detail, the question arises: do telescoped morphologies share a common, convergent function? To our knowledge, the functional-adaptive role played by extensive bone overlap and reduction in maxillo-occipital distance in the cetacean skull has been the focus of little empirical work. However, several hypotheses for the function(s) of telescoping have been described in the literature and some of them are outlined below.

Miller (1923) hypothesized that “compressing forces” during swimming (forces imposed by the body against the back of the skull and resistance of the water against the front) push the back of the skull forward and anterior portions of the cranium back. Miller attributed odontocete- and mysticete-style telescoping, respectively, to fast swimming speeds and bulk feeding (Miller, 1923, p. 35–40). In his view, telescoped skull morphologies did not evolve in other aquatic tetrapods because of their smaller skulls and slower swimming. From the context in which he made this proposal, it seems he may have envisioned these mechanical forces as acting directly during development to produce the morphology. Yet, as we will expand upon below, such a hypothesis does not accord with our observations that telescoping originates in fetuses long before the skull experiences forces from swimming or feeding.

Multiple authors have suggested that telescoped morphologies evolved in response to forces experienced while swimming or diving. Telescoping may strengthen the skull against forces from the water (Howell, 1930) or may allow alignment of the skull and body axis to aid in swimming (Howell, 1930; Courant and Marchand, 2000). It has also been suggested that maxillary and premaxillary overlap evolved to buttress elongate rostra of odontocetes (Oelschläger, 1990; attributed to Abel by Raven and Gregory, 1933).

According to some bioacoustic hypotheses, maxillo-frontal overlap in odontocetes—also described as “sand-wiching” of the bones and suture connective tissue—may assist in echolocation and may do so in two ways: by focusing the sound produced during echolocation and/or by separating sound production in the facial region from sound reception in the ear through serial impedance mismatch (which is the reflection or transmission of the sound as it passes through a series of interfaces between different tissue types) (Fleischer, 1976; see also, Aroyan et al., 2000; Cranford et al., 1996). Some support for these hypotheses may be provided by current evidence suggesting the presence in the earliest known Oligocene odontocete fossils of both echolocation and extensive maxillo-frontal overlap (Geisler et al., 2014; Churchill et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016).

Perhaps the most pervasive hypothesis offered since Miller’s (1923) account is that telescoping arose in association with selection for a repositioning of the nostrils to the dorsal surface of the skull to produce a “blowhole,” which involved a posteriad shift of the external nares and rotation of the nasal passage into a vertical or sub-vertical orientation. Although this hypothesis has often been attributed to Miller (1923), and Miller did comment on a relationship between shortening of the cranium (here termed reduction in maxillo-occipital distance) and the position of the nasal passages (Miller, 1923, p. 26), he did not directly link his observations about cetacean nasal passages to the bone overlap he considered intrinsic to telescoping. Raven and Gregory (1933) were among the earliest authors to associate telescoping with repositioning of the nasal passage. In his 1966 textbook, Romer reinforced this interpretation by stating that “the premaxillary and maxillary bones have been dragged back over the more posterior elements” in the course of the nares’ moving backward to the top of the head, which “result [ed] in a peculiar, telescoped effect” (Romer, 1966, p. 297).

A putative evolutionary relationship between the blowhole, extensive bone overlap, and reduction in maxillo-occipital distance could take several forms: telescoping (as defined here) could have been a passive, correlated response to selection acting most directly on the position and orientation of the external bony nares, or on the bones as anchors for repositioned facial muscles, which are shifted to the top of the head to control the opening and closing of the blowhole (Lawrence and Schevill, 1956; Mead, 1975; Heyning and Mead, 1990; Fordyce, 2002). A telescoped skull might also be a mechanically more robust setting for the use of a blowhole. According to one hypothesis (suggested to us by our colleague Christine Wall) that functionally links the position of the blowhole to bone overlap and maxillo-occipital shortening, reconfiguration of the bones in this region may provide structural reinforcement that prevents the skull from fracturing around the blowhole during the forceful expulsion and inhalation of air in breathing. Alternatively, cranial features associated with the blowhole and those that contribute to telescoping could have evolved independently. Doing as we propose and restricting application of the term “telescoping” to the features to which Miller originally alluded (extensive bone overlap and longitudinal reduction in maxillo-occipital distance) makes it easier to examine the relationship between characteristics directly implied by the metaphor and other features, such as the blowhole, that are distinctive in modern cetaceans.

The explanations provided above are not mutually exclusive: selection for more than one function may have contributed at different times and in different lineages to producing telescoped phenotypes. For instance, overlap could have initially arisen as a correlate of the posterodorsal position of nares in the evolution of the blowhole, but then been co-opted in odontocetes for bioacoustic functions. Discovering the origins and modern functions of telescoping will require an interdisciplinary approach that makes use of thorough descriptions of the variation among species in bones, the sutures, and the anatomical and histological details. The list of possible functions and adaptive values provided here is not exhaustive, but it may provide a starting place for discussion and empirical study of telescoping and its biological role(s) in cetaceans.

Developmental Origins

Evolutionary changes in morphology occur through changes to developmental processes. Embryos and fetuses allow us to observe how cetacean cranial development diverges from that of a typical mammal. As development provides insights into how modern cetaceans build their unusual telescoped skulls (Miller, 1923, p. 40), prenatal stages also clarify what types of modifications to ancestral developmental processes may have contributed to the evolution of telescoped morphologies.

Cetacean embryonic and fetal material in collections is rare; as a result, the literature on cetacean skull development consists primarily of detailed anatomical descriptions of individual fetuses rather than developmental series (e.g., de Burlet, 1914; Eales, 1950; Kükenthal, 1893; von Schulte, 1916; for a comprehensive list, see Thewissen and Heyning, 2007). A relatively small proportion of studies have described observations of skull development in ontogenetic series of fetuses of different sizes and gestational ages within a single species or have attempted to synthesize available descriptions into an understanding of developmental trajectories (Ridewood, 1923; Kuzmin, 1976; Moran et al., 2011; Tsai and Fordyce, 2014; Hampe et al., 2015). Recently, computed tomography has allowed the internal morphology of rare and irreplaceable prenatal cetacean specimens to be examined noninvasively (Roston et al., 2013; Hampe et al., 2015). This has allowed researchers to assemble larger data sets of fetal series to compare development across species (Yamato and Pyenson, 2015). Apart from Moran et al. (2011), most descriptions of embryonic and fetal skulls provided in the literature do not explicitly discuss the origin of telescoped skull morphologies, but some make mention of the presence or absence of bone overlap (e.g., Ridewood, 1923). These descriptions provide ample raw data with which to begin making conclusions about how telescoped cranial morphology arises in development.

Early in development, the heads of cetacean embryos closely resemble those of other mammals at similar developmental stages, but they begin to acquire more typical cetacean shapes in the late embryonic and early fetal stages (Gill, 1927; Štěrba et al., 2000; Thewissen and Heyning, 2007; Roston et al., 2013). This observation is consistent with the finding that early stages of facial development are conserved throughout tetrapods (Young et al., 2014). In the cetacean species that have been described, ossification begins with the maxillae, premaxillae, and supraorbital processes of the frontals—all dermal bones—sometime in the late embryonic time period (e.g., von Schulte, 1916; Ridewood, 1923; Kuzmin, 1976; Štěrba et al., 2000; Moran et al., 2011; Hampe et al., 2015). Endochondral bones of the basicranium (presphenoid, basisphenoid, and occipital bones) begin to ossify slightly later (e.g., von Schulte, 1916; Ridewood, 1923; Kuzmin, 1976; Moran et al., 2011; Hampe et al., 2015). Earlier fetuses have a large fontanelle in the dorsal cranial vault region between the frontals and parietals (and interparietal, depending on the species) (e.g., von Schulte, 1916; Moran et al., 2011; Hampe et al., 2015). The two hallmarks of telescoping, bone overlap and maxillo-occipital proximity, appear to develop progressively in mysticete and odontocete fetuses as the dermal bones expand dorsad from ossification centers. However, in balaenopterids, extension of the supraoccipital anteriad and its overlap over the parietals appears to develop later in gestation than the anterior maxillo-frontal overlap in this group (von Schulte, 1916; Ridewood, 1923; Roston et al., 2013; Hampe et al., 2015).

Much of our discussion of longitudinal reduction of maxillo-occipital distance has focused on the overlapping elements, but bringing anterior and posterior elements into proximity also necessarily involves changes to the dorsal skull roof formed by the parietals and interparietal. In odontocetes, the interparietal makes direct contact with the frontals and separates the parietal bones, preventing contact of left and right parietals on the midline (Rommel, 1990; Mead and Fordyce, 2009). In adult odontocetes, as in many other mammals, the interparietal fuses with the supraoccipital and the suture between them becomes completely obliterated (Mead and Fordyce, 2009; Koyabu et al., 2012). In contrast, for several mysticete species, there is still no consensus whether the interparietal is present in adults or at various stages of development (Tsai et al., 2014; Nakamura et al., 2016). However, in other mammals in which the interparietal had been described as “lost,” it was later found that interparietal ossification centers fuse to the supraoccipital early in development (Koyabu et al., 2012). Determining whether the interparietal is fused to the anterior edge of the supraoccipital, lying over the parietals, or to the ventral surface of the supraoccipital, lying between the parietals, will be key to understanding the biology of mysticete telescoping.

Non-Homology in Mysticetes and Odontocetes

Cetacean telescoping is observed in both mysticetes and odontocetes. When a pair of sister-taxa exclusively share a derived feature, it invites the question: is the trait in the two clades homologous?

As we have described them in preceding sections of this article, and as is widely recognized, the manifestations of bone overlap and maxillo-occipital proximity—the criteria for telescoping as we define it—differ in mysticetes and odontocetes in both anatomical and embryological particulars. As Miller (1923, p.7) observed, “The skull of a finback whale is thus seen to be telescoped in a manner so unlike that of a dolphin that it is at first difficult to understand how two such opposite types could have originated,” and he (pp. 6–7) proposed different evolutionary scenarios and distinct starting points for the evolutionary transformation of “normal mammals” into odontocete and mysticete types. Later, Fordyce and Barnes (1994, p. 423), for example, noted that “In all Odontoceti and Mysticeti, rostral bones and the supraoccipital are ‘telescoped’ (Miller, 1923) toward each other, although such telescoping is not demonstrably homologous in these two groups.”

Thus, the state of telescoping manifested in these two major subclades of Neoceti would appear to fail Patterson’s (1982) first criterion for homology, that of similarity. Invoking Remane’s three more detailed “principal criteria” by which homology can be recognized among similarities, there seems little reason to propose that mysticete and odontocete telescoping are homologous: (1) the positional criterion: “similar position in comparable systems of features”; (2) the structural criterion: “similar structures can be homologized, without similar position, when they agree in numerous special features”, and “certainty increases with the degree of complication and of agreement in the structures compared”; and (3) the transitional criterion: “even dissimilar structures of different position can be regarded as homologous if transitional forms between them [pairs of neighboring forms, in ontogeny or phylogeny, that fulfill criteria (1) and (2)] can be proved” (Remane’s 1971 criteria as translated by Riedl, 1978, p. 34).

It could be argued that the presence of a distinct ascending process of the maxilla that overlies the frontal is a similarity that is shared by modern mysticetes and odontocetes and (as described above in “The Fossil Record”) is even observed in their archaeocete predecessors. However, as we have also noted there, we do not equate this one feature with telescoping (nor did Miller, 1923). The condition of this one element in odontocetes and mysticetes might qualify as homologous (see Miller, 1923, pp. 7–8). But homologizing this single feature is a different matter from assessing homology for the global structural attribute of telescoping.

As has been noted above, among ziphiid and physeteroid species of odontocetes and balaenopterid mysticetes, there exist cases in which both anterior and posterior elements (in single individuals) contribute to telescoping. These combinations of characteristics of both mysticete and odontocete telescoping indicate that the two conditions also fail Patterson’s (1982) second test of homology, that of conjunction. Conjunction—or co-occurrence of two characters in the same individual organism—disqualifies the two from being “anatomical singulars,” as Patterson (1982, echoing Riedl’s, 1978, p. 52, account) referred to morphological homologues. That is, they cannot be one and the same: not one state of the same character or two alternative states of the same character. Rather, they must be states of two distinct characters and therefore not homologous.

It is plausible that some anatomical details of the features of telescoping, such as the ascending process of the maxilla, are synapomorphies for Odontoceti + Mysticeti (Barnes, 1990; Geisler and Sanders, 2003). The possibility also exists that an innovation in developmental physiology present in the common ancestor of these two lineages, but ultimately expressed in different regions of the skull, has allowed cranial bones that ordinarily either fuse or abut one another at sutures to override one another instead. A synapomorphy (or symplesiomorphy) of this sort would be a challenge to demonstrate regardless of whether it arose in one lineage or two. However, the developmental mechanisms that have given rise to the extremely divergent morphologies of the two clades of cetaceans— as well as the evolutionary and developmental mechanisms that have prevented other mammals from expressing similar traits—are of compelling interest.

TELESCOPING AND CRANIAL SUTURES: A FRONTIER FOR RESEARCH

Cetacean telescoping, although most commonly described in terms of the positioning of bones (e.g., Moore, 1981), also, fundamentally, reflects radical changes in cranial sutures: “Alteration of contact-relationship is here not the exception but the rule” (Miller, 1923, p. 2). What Miller meant by “contact-relationship” can be interpreted in two ways: the topological connectivity and adjacency of bones (which in other taxa has become a focus of “anatomical network analysis”; Rasskin-Gutman and Esteve-Altava, 2014) or the histology and morphology of the suture interface itself (e.g., Bailleul and Horner, 2016). Both of these aspects of contact relationships have been altered in cetacean telescoping and both point to sutures as a source of unresolved biological questions that are avenues for continuing research.

What Is a Suture?

Sutures are fibrous joints (synarthroses) between bones (Di Ieva et al., 2013). Conversely, cranial bones are masses of vascularized, mineralized skeletal tissue separated by sutures. Situated on either side of a cranial suture are two osteogenic bone fronts (cambial layers), whose growth toward and eventual arrival close to one another in development produces the suture. The suture’s fibrous connective tissue joins the opposing cambial layers (Pritchard et al., 1956) and contains populations of sutural stem cells. These stem cells give rise to skeletogenic cells (osteoblasts and ultimately osteocytes) that are indispensable for growth, homeostasis, and repair of injuries in the skull (Zhao et al., 2015; Maruyama et al., 2016). Many sutures remain patent (the bones flanking them remain distinct) throughout life (Opperman, 2000); other sutures, depending on the species, eventually fuse (that is, become obliterated when the bones adjoining them fuse together) and, in the region of suture fusion skull, growth slows (Herring, 1974). Premature suture fusion often leads to gross deformities in the skull that can impair important sensory, cognitive, and physiological functioning (Morriss-Kay and Wilkie, 2005). Patent sutures, as flexible regions between the bones, are also important biomechanically for the transmission of forces or absorption of energy from compressive or tensile stresses within the skull (Jaslow, 1990; Adamski et al., 2015).

The margins of the bones articulating at a suture may take any of several forms, such as abutting, interdigitating, overlapping (Hildebrand, 1995; Rommel et al., 2009; Sperber et al., 2010). Each of these suture types has different mechanical consequences for strength and flexibility, both locally and throughout the skull (reviewed in Herring, 2008). Many sutures are also developmentally plastic: their morphology can change as the bone fronts adjacent to them are modeled and remodeled in response to mechanical stresses, and different types of articulations may form according to the local mechanical environment (Moss, 1957). Through mechanotransduction, the conversion of mechanical stimulus into electrochemical activity, stresses on tissues and cells affect expression of various genetic transcription factors; these in turn affect cell proliferation, differentiation, and matrix synthesis (Mao and Nah, 2004). Thus (to paraphrase Mao and Nah, 2004:676), in modulating suture form, mechanical forces share mechanisms with hereditary influences through their effects on genetic pathways.

Suture Development in Telescoped Skulls

Sutures that lie between bones that overlap to some degree at their margins are found in all mammalian skulls. But sutures in telescoped regions of cetacean skulls (termed “horizontal sutures” by Gatesy et al., 2013) must span large areas of bone overlap and cover expansive adjoining surfaces. Over the braincase, the presence of a double layer of bone separated by a sutural surface presents problems for skull development and—for reasons that we detail below—would not be predicted on the basis of current knowledge of skull development and growth in other mammals. For telescoped bone-and-suture configurations to have evolved, developmental mechanisms must have been acquired that both produce and accommodate growth in the region of extensive bone overlap. In the following paragraphs, we will raise questions that call for continuing research.

A telescoped morphology initially develops in utero and is present at birth (Perrin, 1975; Rauschmann et al., 2006). Thus, it arises well before the skull experiences the forces of swimming invoked by Miller (1923, p. 39; discussed above). In other mammals, ossification of intramembranous bones such as the maxillae and frontals (which participate in odontocete telescoping, the type we will address first) spreads from ossification centers until two ossification fronts meet and either fuse immediately or form a suture between them (Moss, 1954; Rice, 2008). How does extensive overlap arise between these bones in cetaceans when in other mammals—even in the region of an overlapping suture—the overlap between bones is minimal? One possibility is that in cetaceans these developing bones slide over one another—that is, their membranous primordia are displaced—before a suture is formed. However, it is unclear where or from what the forces producing such morphogenetic movements would originate, or what this would imply about the properties of tissues surrounding and lying between the bones. Alternatively (or subsequently, even if the bones’ overlapping position is initially caused by movement), overlap could occur with continued growth of adjacent bones at their margins. What differences in the osteogenic bone fronts of telescoping bones allow them to extend growth past one another, rather than stop, coordinate, and develop sutural material between their opposing margins? Is the suture layer that eventually develops between the surfaces of the two bony layers morphologically structured in a way analogous to a more typical suture? Is the entire surface of each bone in the regions of contact between the maxilla and frontal a cambial layer, like those in the opposing bone margins that flank the fibrous connective tissue of a typical suture?

Because telescoped morphologies occur surrounding the cranial vault, the double layer of bones presents a problem for brain growth in that region. Numerous studies have shown that growth of the cranial vault in mammals occurs by two mechanisms (Sperber et al., 2010): bone apposition at the sutural margins between bones, at least partially induced by tensile strain on the suture from brain expansion; and extracranial surface apposition with intracranial surface resorption. However, in a region of extensive overlap, apposition in the suture margins would not lead to growth of the cranial vault, brain expansion would produce compressive, not tensile forces on a “horizontal suture,” and surface apposition and resorption would erode away the deeper of the two layers of bone. Growth of mammalian skulls involves a highly coordinated interplay of brain expansion and bone growth stimulated by signaling from the dura mater (Sperber et al., 2010). In the highly overlapped region, a large portion of the external surface of the cranial vault is covered by a bone that appears not to have direct contact with the dura mater, an important source of growth signals for sutures (Ogle et al., 2004).

Much of our discussion here has focused on the development of overlap between the intramembranous bones maxilla and frontal, and similar questions arise for understanding the overlap of the parietal from behind by the occipital (and possibly interparietal) in mysticetes. Is the bone that overlaps the parietals in mysticetes another intramembranous bone, the interparietal? As Tsai et al. (2014) have discussed, the presence versus absence of this bone in mysticetes has been disputed for some mysticete species, whereas for others, the presence of an interparietal has been reported (Nakamura et al., 2016). Endochondral bones, such as the occipital, form through ossification of a cartilaginous scaffold. If the occipital, and not the interparietal, is indeed the bone that overlies the parietals in mysticetes, does telescoping that involves endochondral bones involve the same processes and follow the same “rules” as telescoped intramembranous bones?

Cetaceans are (obviously) not commonly considered model systems for developmental biology. Yet the unusual arrangements of cranial bones and sutures that define telescoping (in its varied manifestations) are not easily explained by what is known about cranial development in more conventional mammals. Thus cetaceans may ultimately serve as natural experiments that will both challenge and enhance our understanding of mammalian sutures and cranial development.

The Evolutionary Modification of Sutures in Telescoped Skulls

It was noted above that suture morphology is to some extent plastic and influenced by forces produced by muscles inserting on the bones and by growth of neighboring tissues. Nevertheless, sutures’ responsiveness to mechanical stresses has genetic underpinnings, and variability in the developmental mechanisms affecting suture plasticity is likely also heritable. Plasticity itself has been shown to evolve (Nijhout, 2003; West-Eberhard, 2003; Suzuki and Nijhout, 2006; Beldade et al., 2011), and selection may favor individuals that have a genetic predisposition to develop a specific suture shape or a certain responsiveness to environmental stimuli. An example of heritable variation in a configuration of cranial sutures has been documented in the free-ranging colony of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) introduced onto Cayo Santiago, family pedigrees suggesting it is heritable as an autosomal recessive trait (Wang et al., 2006). This same trait also shows variation at macroevolutionary scales, as frequencies of this variant are biased in different ways in different species (Ashley-Montagu, 1933; Wang et al., 2006; Fulwood et al., 2016).

The questions that arise about sutures between overlapping bones in telescoped skulls—the developmental “problems” that telescoped morphologies present at the sutural interface—suggest that variation in the sutures themselves, not simply the bones they separate, may be targeted by natural selection for adaptive change. In most descriptions of suture evolution in other mammals, sutures are treated as if they are the passive boundaries between bones (where discussion has focused) rather than complex three-dimensional organs with biological and historical dynamics of their own (Depew et al., 2008). Numerous studies have described suture fusion and obliteration sequences and either used evolutionarily informative or conserved patterns as taxonomic characters in phylogenetic reconstruction or mapped the patterns on phylogenetic trees to reconstruct ancestral traits (e.g., Bärmann and Sánchez-Villagra, 2012; Goswami et al., 2013; Rager et al., 2014; Wilson, 2014). Suture fusion patterns have been compared to known ontogenetic sequences to estimate ontogenetic ages in fossils and extant species (e.g., Meindl and Lovejoy, 1985; Key et al., 1994; Nawrocki, 1998; Cole et al., 2003; Bailleul et al., 2016), and intersecting sutures are commonly used as landmarks for morphometric analyses of skull shape (e.g., Rohlf and Bookstein, 1990; Zelditch et al., 1992; Goswami, 2006; Porto et al., 2009). But beyond studies that document the presence, absence, and positions of patent sutures, little attention has focused on the evolution of the developmental processes in which sutures participate.

The heritable sutural variants in Cayo Santiago macaques mentioned above are in the pterion region of the skull, where five bones (frontal, parietal, zygomatic, sphenoid, temporal) articulate in various combinations, with at least two of these bones excluded from direct articulation (Ashley-Montagu, 1933). The polymorphism pertains to which pairs of bones articulate, preventing contact between the others. Although frequencies of the polymorphisms differ among primate species, it has been suggested that the direction of the bias in frequency, rather than being structured strictly phylogenetically, may instead be influenced by cranial length-height ratios (Wang et al., 2006). This suggestion implies that whether or not bones are excluded from contact could depend upon growth processes: the initial proximity of ossification centers and/or relative rates of bone accretion. This example of the primate pterion polymorphism is a situation that, for other areas of the skull, cetaceans have circumvented. To these kinds of alternatives, cetaceans have added in their telescoped regions yet another possibility and another dimension of growth. Here, a growing bone does not just form a suture and coordinate growth when it meets another bone. Instead, the bone that does the overlapping in a telescoped skull can override a bone it meets and continue growth toward others situated beyond it.

What about cetacean biology has allowed them to achieve morphologies like this, which are unobserved in other organisms? Is the ability of a skull to telescope a result of selection for the breaking of a developmental constraint that in other mammals prevents extensive bone overlap? In more concrete, empirical terms, for example, when nonadjacent bones grow toward one another and come into very close contact, do they form a suture between them whose structure is like those between normally adjacent bones? More specifically, in taxa in which the maxillae and/or nasals appear to contact the supraoccipital (e.g., B. musculus, according to Miller, 1923; Balaenoptera siberi, Pilleri, 1989; Wimahl chinookensis, Peredo et al., 2018), does a suture form between these formerly nonadjacent bones? Ultimately, what aspects of cetacean biology have allowed cetaceans, uniquely, to evolve telescoped morphologies, and to do so more than once?

Telescoping raises many macroevolutionary questions relevant to cetacean evolution, the evolution of typical mammal skulls, and the macroevolutionary consequences of an evolutionary innovation. Cetaceans are well-suited for comparative study as they are themselves a diverse taxonomic group nested within terrestrial artiodactyls, another diverse group (Gatesy et al., 2013). Comparative approaches in studying extant taxa foster the generation of hypotheses of evolutionary scenarios that can be tested using the robust cetacean (and artiodactyl) fossil record (e.g., Gatesy et al., 2013; Geisler et al., 2014; Churchill et al., 2016; Geisler et al., 2017). Within this phylogenetic and comparative context, telescoping can provide models for how evolutionary innovations in development affect patterns of macroevolutionary change.

Sutures, often characterized as linear (if meandering) paths through three-dimensional space, may in telescoped skulls most accurately be viewed as rugged or undulating surfaces (Fig. 2). What does telescoping suggest about how patterns and magnitudes of covariance (reflecting integration) or the relative independence of parts (modularity) can evolve (Goswami, 2006; Marroig et al., 2009; Porto et al., 2009; del Castillo et al., 2017)? Does extensive overlap between bones affect the covariance and relative independence of skull bones as individualized units? If individual bones can vary more independently of one another because telescoping accords them additional dimensions of variability, cetacean skulls could be more modular than the skulls of other mammals; alternatively, cetacean skulls could display more integration, if broad areas of contact between bones make bone shapes more dependent on the shapes of their direct neighbors. As Marx and Fordyce (2016) observed in the vertices of mysticetes, telescoping can impose reciprocal variation between previously nonadjacent bones brought newly into proximity. Telescoping increases theoretical morphospace (sensu Raup, 1966; McGhee Jr., 1999) for mammalian skulls by introducing additional parameters of variation (e.g., the extent of overlap), thereby increasing possible dimensions of variability and adaptive versatility (sensu Vermeij, 1974).Changes to theoretical morphospace and changes in the accessibility of specific regions within it qualify telescoping as an evolutionary innovation and may have allowed cetaceans to acquire novel functions and allowed their lineages access to new adaptive peaks (Maynard Smith et al., 1985; Hallgrímsson et al., 2012). Qualitative observations discussed in detail above (“The Fossil Record”) suggest that diversification within the two extant suborders occurred after the origin of the two main bauplans of telescoping and that this was followed by divergent manifestations of these telescoped skull morphologies among extant cetacean families. Depending on its functional role within the skull, the details of telescoping may have biased (and been biased by) the evolutionary trajectories of feeding habits, swimming styles, communication, or hunting strategies.

By permitting bones to override one another, rather than abut and fit together to form a single surface, telescoping enhances decoupling of overall skull shape from the shapes of its bony subunits. Studies of mammalian skull integration and modularity have often made use of landmarks defined in relation to overall skull shape (e.g., points at anatomical extremes, such as tip of the rostrum, or points reflecting changes in curvature: notches and bulges) or relationships between bones (e.g., points defined by intersecting sutures), but few studies have directly examined the relationships between hierarchical levels of skull organization, such as the covariance of overall skull shape with the sizes and shapes of constituent bones (but see Pearson and Woo, 1935).