Abbreviations

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- AR

acute rejection

- CI

confidence interval

- GGT

gamma‐glutamyl transferase

- HCT

hematopoietic cell transplantation

- HVPG

hepatic venous pressure gradient

- IQR

interquartile range

- LT

liver transplantation

- PH

portal hypertension

- SHR

subhazard ratio

- SOS

sinusoidal obstruction syndrome

- TIPS

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

To the editor,

Diagnosis of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is based on clinical criteria including weight gain, ascites, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.[ 1 ] However, clinical and histological features and prognosis of SOS after liver transplantation (LT) seem to differ from SOS after HCT.[ 2 , 3 ] We aimed to determine the characteristics and outcomes of SOS after LT.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Possible SOS cases

A case report form was sent to the 24 adult LT units in Spain. Twenty units agreed to participate, including 12,941 LT procedures.

Suspected SOS cases were identified as follows: In 43 cases, after SOS clinical suspicion, a local confirmatory biopsy was available. In the remaining, SOS was established after identification of a biopsy coded with SOS diagnosis (n = 7). These biopsies were indicated based on non‐SOS–related clinical reasons or by protocol.

In all cases, hepatic vein thrombosis and anastomotic stenosis were ruled out.

Central confirmation of SOS

Fifty patients were identified as possible SOS cases and centrally reevaluated as follows.

Clinical evaluation

All possible SOS cases were independently reviewed by 2 hepatologists (M.S. and A.C‐M.) blinded to histological findings.

Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) was available in 30 out of the 50 suspected SOS cases and considered an additional diagnostic criterion. Acute rejection (AR) and antibody‐mediated rejection were specifically documented.

Histological evaluation

Two liver pathologists (I.P. and J.P‐R.) blinded to clinical findings and previous pathological diagnosis independently reviewed all biopsies (80 from 50 LTs) stained with hematoxylin‐eosin, Masson’s trichome, and reticulin. Histologic assessment included parameters proposed by Rubbia‐Brandt et al.[ 4 ] Vascular injury and/or perisinusoidal/central venous fibrosis were mandatory to establish SOS diagnosis.

Final diagnosis

After independent assessment, each case was jointly reviewed to assign a final diagnosis. SOS diagnosis was resolved in favor of histological diagnosis when differences between clinical and histological evaluation appeared. Finally, 41 cases were diagnosed with SOS.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed as appropriate according to data distribution. Survival rates were calculated and compared with the Kaplan‐Meier method and log‐rank test, respectively. Competing risk analysis was performed to estimate incidence of retransplantation considering death as a competing event. A multivariate Fine and Gray regression analysis was performed, providing subhazard ratio (SHR) for SOS‐specific treatment.

RESULTS

Patientsʼ characteristics

The median age at diagnosis was 51 years (interquartile range [IQR] 44.0–57.5), and 75.6% were male. The most frequent LT indications were advanced cirrhosis (51.2%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (31.7%). Tacrolimus was predominantly used during the first month after LTs, in combination with either steroids (21.1%) or steroids and mycophenolate mofetil (36.8%).

SOS presentation

No patient showed the classical triad of hepatomegaly, ascites, and jaundice. Ascites was very frequent at the time of diagnosis (80.5%), whereas jaundice was present in only 39.0% of cases. At the time of histological diagnosis, six patients had unspecific clinical findings.

HVPG was measured in 26 patients, being >6 mm Hg in 25 (96.2%). A total of 21 (80.8%) patients had clinically significant portal hypertension (PH; ie, HVPG >10 mm Hg).

AR was diagnosed in 13 (31.7%) patients, 7 of them (53.9%) before SOS onset. No cases of antibody‐mediated rejection were identified.

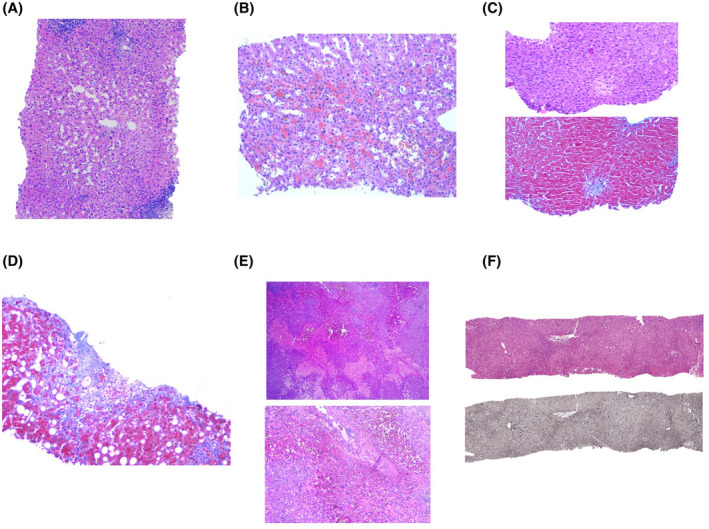

Most patients showed sinusoidal dilatation (97.6%; Figure 1A). Perisinusoidal hemorrhage (75.6%; Figure 1B) and centrilobular vein fibrosis (75.6%; Figure 1C,D) were also common. Peliosis (24.4%; Figure 1E) and nodular regenerative hyperplasia (26.8%; Figure 1F) were less frequent.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Sinusoidal dilatation around central vein (zone 3). (B) Perisinusoidal hemorrhage and sinusoidal dilatation. (C) Centrilobular vein fibrosis (hematoxylin‐eosin and Masson’s stain), obliterative fibrous lesion. (D) Centrilobular vein fibrosis, evolved obliterative lesion. (E) Peliosis hepatis. Irregular blood‐filled cavities with no endothelial lining (hematoxylin‐eosin). (F) Nodular regenerative hyperplasia (hematoxylin‐eosin and reticulin stain). The nodularity results from zones of atrophic hepatocytes alternating with areas of normal‐sized hepatocytes

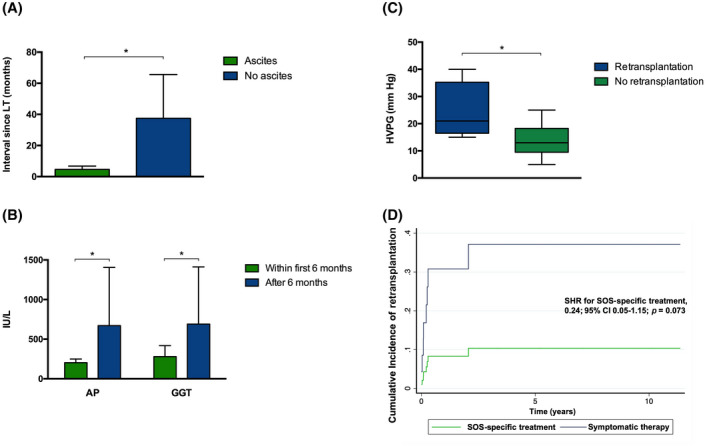

The median time between LT and SOS onset was 2.43 months (IQR 1.64–11.01). Many patients (70.7%) were diagnosed within the first 6 months after LT, showing more frequently ascites (95.6% vs. 41.7%, p < 0.001; Figure 2A). Patients who presented SOS beyond 6 months after LT more frequently presented cholestasis (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Clinical presentation of SOS. (A) Interval between LT and SOS onset according to the presence of ascites. Bars represent mean time from liver transplantation to SOS in months. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. (B) AP and GGT levels according to the interval between LT and SOS. Bars represent mean levels of AP and GGT. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. (C) Comparison of HVPG according to the need of retransplantation. The box ranges from Q1 (the first quartile) to Q3 (the third quartile) of the distribution and the range represent the IQR. The median is indicated by a line across the box. The whiskers on box plots extend from Q1 and Q3 to the most extreme data points. (D) Cumulative incidence of retransplantation in the presence of competing risks in patients with SOS according to the type of treatment. Retransplantation as the event of interest and death as the competing event. (*p < 0.005)

SOS management and outcomes

The median follow‐up was 31.08 months (IQR 9.43–71.63). Seventeen patients (41.5%) received only symptomatic therapy with diuretics, sodium restriction, and paracentesis. Thirteen patients (31.7%) received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), with initial improvement in most of them (n = 9, 69.2%). Six out of seven cases with post‐TIPS HVPG measurements (85.7%) had a HVPG values in the normal range. However, only one of the five cases who underwent a control liver biopsy showed SOS resolution. Moreover, two patients (15.4%) who initially presented clinical resolution required retransplantation after TIPS.

Five patients (12.2%) received defibrotide (median time between SOS onset and defibrotide: 14 days [IQR 4–16]). Unlike TIPS, defibrotide achieved histological resolution of SOS and PH in four patients (80.0%). Furthermore, defibrotide resolved clinical manifestations in three patients (60.0%). No drug‐related adverse events were described. Six patients (14.6%) received anticoagulation (n = 3) or a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor to minimize or stop tacrolimus (n = 3).

Six patients (14.6%) died (median follow‐up 31.08 months [range 0.37–138.2]), three of them (50.0%) due to SOS. Nine patients (22.0%) required retransplantation. SOS recurrence was not observed after retransplantation. Patients who required retransplantation had greater HVPG at diagnosis (Figure 2C). Moreover, patients with an initial HVPG over 20 mm Hg required retransplantation more frequently (88.9% vs. 11.1%; p = 0.02). The cumulative retransplantation‐free survival rates at 5 and 10 years were 65.3% and 58.1%, respectively.

Besides similar baseline characteristics, retransplantation was more frequently required in patients who received only symptomatic therapy, compared with patients who received SOS‐specific treatment (62.5% vs. 22.2%; p = 0.06).

Patients who received SOS‐specific therapy showed a decreased risk of retransplantation (SHR for SOS specific treatment, 0.24; 95% confidence interval 0.05–1.15; p = 0.07) considering death as a competing event (Figure 2D).

DISCUSSION

We report the largest multicenter series of SOS cases after LT aiming to ascertain its specific characteristics and clinical implications.

We observed that the classic triad described for SOS after HCT[ 1 ] is extremely infrequent, with isolated ascites being the most common clinical presentation after LT. Thus, consideration of SOS among the causes of graft dysfunction is essential to avoid misdiagnosis. Moreover, we have shown that the clinical presentation pattern depends on the time of presentation. In fact, ascites is the most common presentation when SOS is diagnosed early after LT, while cholestasis is predominant in cases that appear later.

In our series, SOS was associated with poor outcomes, including SOS‐related deaths and retransplantations. Therefore, standardized diagnostic criteria for the specific setting of LT are needed. Considering our results, emphasizing the nonspecific clinical features, histological evidence is essential to establish the diagnosis after LT. According to the proposed pathogenetic SOS mechanisms, vascular injury and/or perisinusoidal/central venous fibrosis should be considered the landmark to establish SOS diagnosis.[ 5 ]

Another important finding is the clear influence of PH in SOS survival and need for retransplantation. We found a threshold HVPG value (>20 mm Hg) that identifies a population at greater risk. Thus, inclusion of HVPG measurement should be part of the diagnostic workup.

Finally, we have found that patients treated only with symptomatic therapy are more likely to require retransplantation after SOS diagnosis. Therefore, SOS‐specific therapies, such as defibrotide or TIPS, should be considered.

In conclusion, this case series provides valuable information helping in the diagnosis and management of SOS after LT.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Jordi Colmenero consults for and is on the speakers' bureau for Chiesi. He is on the speakers' bureau for Astellas. The other authors do not have any conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mohty M, Malard F, Abecassis M, Aerts E, Alaskar AS, Aljurf M, et al. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno‐occlusive disease: current situation and perspectives—a position statement from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:781–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sebagh M, Azoulay D, Roche B, Hoti E, Karam V, Teicher E, et al. Significance of isolated hepatic veno‐occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:798–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sebagh M, Debette M, Samuel D, Emile J‐F, Falissard B, Cailliez V, et al. “Silent” presentation of veno‐occlusive disease after liver transplantation as part of the process of cellular rejection with endothelial predilection. Hepatology. 1999;30:1144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubbia‐Brandt L, Lauwers GY, Wang H, Majno PE, Tanabe K, Zhu AX, et al. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and nodular regenerative hyperplasia are frequent oxaliplatin‐associated liver lesions and partially prevented by bevacizumab in patients with hepatic colorectal metastasis. Histopathology. 2010;56:430–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sinusoidal R‐B, Syndrome O. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:651–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]