Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic raised acute awareness regarding inequities and inequalities and poor clinical outcomes amongst ethnic minority groups. Studies carried out in North America, the UK and Australia have shown a relatively high burden of asthma and allergies amongst ethnic minority groups. The precise reasons underpinning the high disease burden are not well understood, but it is likely that this involves complex gene–environment interaction, behavioural and cultural elements. Poor clinical outcomes have been related to multiple factors including access to health care, engagement with healthcare professionals and concordance with advice which are affected by deprivation, literacy, cultural norms and health beliefs. It is unclear at present if allergic conditions are intrinsically more severe amongst patients from ethnic minority groups. Most evidence shaping our understanding of disease pathogenesis and clinical management is biased towards data generated from white population resident in high‐income countries. In conjunction with standards of care, it is prudent that a multi‐pronged approach towards provision of composite, culturally tailored, supportive interventions targeting demographic variables at the individual level is needed, but this requires further research and validation. In this narrative review, we provide an overview of epidemiology, sensitization patterns, poor clinical outcomes and possible factors underpinning these observations and highlight priority areas for research.

Key messages.

Greater burden and poorer clinical outcomes among ethnic minority groups with allergic diseases are reported

Reasons involve deprivation, literacy, proficiency of local language, access to specialists, cultural and religious beliefs

Priorities include improved access/referral pathways, co‐produced and evaluated interventions, delineation of ethnicity‐specific phenotypes and endotypes

1. INTRODUCTION

Healthcare inequities and inequalities have been recognized as a major problem in high‐income countries (HICs) such as the UK and USA for over two decades. The COVID‐19 pandemic attracted major attention and renewed interest on this subject owing to disproportionate high mortality amongst patients from ethnic minority groups. Healthcare disparities have been linked to multiple socio‐demographic variables including age, gender, socio‐economic status, geographical location, cultural and religious factors. 1 Evidence suggests a strong intersection between poor clinical outcomes and deprivation and literacy, as a significant proportion of the ‘most deprived population’ and those with poor general and health literacy are likely to be from ethnic minority groups. 2 This is highly relevant in patients with allergies and allergic conditions as clinical outcomes depend on patient education and empowerment with implementation of self‐management plans. Whilst socio‐demographic variables are likely to strongly impact on clinical outcomes, it remains unclear at present if disease severity is intrinsically greater in ethnic minority patients resident in HICs.

This narrative review is structured to provide an overview of disparities in allergic diseases amongst patients from ethnic minority groups including epidemiological aspects, risk of sensitization and patterns and clinical outcomes. Reasons underpinning these disparities and mitigation strategies going forward to address gaps in research and healthcare are also incorporated in subsequent sections. The approach adopted by majority of studies presented in this review involves comparison of specific ethnic minority groups with reference white population.

2. ALLERGIC DISEASES IN ETHNIC MINORITY POPULATION IN HICS—DISPARITIES AND POOR CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Table 1 for an overview

TABLE 1.

Summary of published ethnicity‐based disparities in allergic diseases in high‐income countries

| Key observations | |

|---|---|

| Epidemiology |

|

| Sensitization |

|

| Clinical aspects |

|

Adjusted incident rate ratios (95% C.I).

2.1. Allergic rhinitis and asthma

Most published evidence on this subject comes from North America, with few studies from the UK, Europe and Australia. A recent large retrospective longitudinal cohort study in the UK primary care involving six million patients showed that the incident risk of common allergic diseases including allergic rhinitis, asthma and atopic eczema is greater amongst South Asians, Afro‐Caribbean's and those from mixed ethnic groups. 3 In another longitudinal cohort study spanning over 25 years, the same authors showed that the long‐term risk of organ‐specific and systemic autoimmune disorders was significantly greater in the British patients with a pre‐existing allergic disease. 4 These observations raise further questions regarding gene–environment interactions, as allergic diseases and autoimmune disorders are relatively less prevalent in low‐income countries and low‐middle‐income countries such as in the Indian subcontinent and Africa. 5 , 6

One study from the USA reported that the adverse impact of allergic rhinitis on African American children was greater than that reported amongst Latinos and non‐Latino white patients. 7 There is similar evidence regarding a higher risk of atopy amongst South Asian British children. 8 The Allergy and Infection study reported that Pakistani children were more likely to be sensitized to house dust mite than white children. 8 Also, a greater proportion of children whose mothers were born outside the UK were sensitized to dust mite in comparison with those whose mothers were born in the UK. 8

Data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that the prevalence of asthma is greater amongst Black Americans, Puerto Ricans and mixed‐race patients in comparison with Hispanics, Asians and non‐Hispanic white patients over the last 2 decades. 9 Furthermore, prevalence is greater in those belonging to lower socio‐economic strata. Asthma morbidity is also greater amongst Black American patients in comparison with white patients with respect to number of emergency room visits and hospitalizations. The US CDC 2017 data also reported higher rates of fatal asthma amongst Black non‐Hispanic patients in comparison with white non‐Hispanics, other non‐Hispanic and Hispanic patients (Table 1). 10

Data from the UK severe asthma registry and the optimum patient care research database showed that, as compared to the white population, the ethnic minority population was more atopic, expressed higher type 2 inflammation markers and serum total immunoglobulin E (IgE), had lower lung function and worse asthma control. 11 The refractory asthma stratification programme demonstrated that patients from ethnic minority groups were less likely to adhere to treatment advised in the clinical trial and had higher asthma exacerbations than white patients. 12 Current guidelines for the use of biologics in asthma are based on data from translational research and clinical trials conducted mainly in white populations from HICs. Whilst ethnicity is considered to be mainly a social construct, a recent case‐control study from the USA involving African American, Mexican and Puerto Rican children highlighted key differences in blood parameters influencing eligibility for biologic therapies. 13 Serum total IgE was significantly higher in Puerto Rican children compared with the other two groups. Peripheral blood eosinophil and neutrophil counts were significantly greater amongst Puerto Rican patients compared with African Americans. A greater proportion of Puerto Ricans were ineligible for anti‐IgE therapy in comparison with African American and Mexican patients. Similarly, a greater proportion of African American patients were deemed ineligible for eosinophil directed therapies compared with Puerto Ricans. 13 This study highlights the need for (1) defining reference ranges for key blood parameters in ethnic minority groups, (2) developing selection criteria for biologic therapies to be more equitable and (3) ensuring drugs in development address the mechanism of disease in the non‐white population rather than assuming it is the same. Poor inclusion of the non‐white population in research results in the potential for white dominant therapies.

2.2. Food allergy and anaphylaxis

In the Learning Early About Peanut (LEAP) study, the relationship between skin prick test (SPT) response and specific IgE level to peanut differed significantly in the black population, the so‐called Simpson paradox (i.e. a statistical association or trend that appears for two groups with a particular variable is opposite when data for the two groups are combined). This may lead to over diagnosis of allergy if SPT profiles alone are used for black children. At study entry, participants were twice as likely to be in the peanut positive stratum if they were South Asian as white. 14 , 15 In the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study, only 199 of the infants enrolled were non‐white compared with 1104 white participants. At enrolment, within group sensitization to one or more foods significantly differed by ethnicity—black/south Asian (48.6%), Mixed (22.9%) and white (12.3%). 16 In the standard introduction group, the proportion of food allergy cases by ethnicity was 28.6% in the white study population and 71.4% in the non‐white study population, which was incongruent with the overall study population (84.7% white vs. 15.3% non‐white). 17 A recent study from the USA noted higher rates of self‐reported food allergies amongst ethnic minority groups including Black and Asian patients, in comparison with white patients (11.2% and 11.4% vs. 10.1%). 18 Furthermore, the authors reported that the prevalence of food allergies and other allergic conditions, such as asthma, eczema and allergic rhinitis, were significantly higher amongst deprived patients. Similar observations regarding greater prevalence and severity of food allergies, more frequent emergency room visits and food insecurity has been reported amongst ethnic minority groups in the USA and Australia. 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 A study from the USA, employing electronic medical records in 2.7 million patients, reported a higher prevalence of food allergies and intolerances amongst the Asian population. 22 There is also some evidence regarding a higher rate of self‐reported peanut allergy, tree nut allergy and sea food allergy amongst Black American patients compared with white American patients. 18 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 Interestingly, a rural–urban contrast with respect to food allergy prevalence was reported in a study from South Africa, with lower rates amongst children from rural communities. 26

In the UK, Dias et al. 27 established that 52.6% of paediatric allergy referrals were from a non‐white population compared with 35.9% in the general paediatric clinic and the complexity of allergic disease was greater in the non‐white population with them having more food allergens (2.05 vs. 1.22). Over a 14 year time period from 1990 to 2004, Fox et al. 28 found that the proportion of children with peanut allergy from a non‐white heritage increased significantly from 26.8% to 50.31%, this was not the case in the white group or for egg allergy.

In a cross‐sectional survey in the USA involving 385 caregivers of Black and white American children with physician diagnosed food allergies, Vincent et al. 29 reported association of knowledge, behaviour and attitude with socio‐economic status, ethnicity and clinical factors. Carers of Black children had comparatively lower knowledge scores regarding food allergy. Children of carers with higher food allergy knowledge scores were less likely to consume foods with precautionary allergy labels and more likely to consume allergen free foods. However, no differences were detected in emergency room visits between the two groups for severe food allergy reactions. 29

The timing of food allergen introduction during infancy has an important implication on risk of food allergies during childhood. The food allergy outcomes related to white and African American racial differences cohort reported ethnicity‐based differences in the introduction of food allergens early in infancy amongst children with parent‐reported food allergies. 30 African American children with an allergy to peanut, milk or egg were less likely to be introduced to respective allergens early in infancy compared with white children, although reasons underpinning the delay were not explored. Within the LEAP study, early introduction of peanut to high risk infants, between the ages of 4 and 11 months, was shown to significantly reduce the likelihood of peanut allergy at 60 months of age. 15 When this primary outcome was stratified by race, peanut consumption was shown to be significantly more effective at reducing peanut allergy in the non‐white infants, whilst in the avoidance group, a higher percentage of non‐white infants developed peanut allergy. This raises questions as how best to target this intervention to ensure maximal benefit. The EAT study looked at early introduction of six allergens into an infant diet from 3 months of age to prevent food allergy. At the end of the study the intervention did not reach statistical significance for the primary outcome, but it was noted that the food allergy rates were higher in the non‐white participants, and that this group (especially South Asians), were less able to introduce new foods according to protocol in the weaning period. 17 This again raises the question of how we can ensure appropriate education to these groups in any population‐based intervention.

Buka et al. 31 systematically reviewed emergency room records of anaphylaxis occurring in Birmingham, UK and reported a higher rate in the British South Asian patients in comparison with white patients. The age‐standardized incidence rate for anaphylaxis and severe anaphylaxis was 58.3 (42.8–76.3, 95% C.I) and 20.4 (10.6–33.1, 95%, C.I) cases per 100,000 person years respectively for British South Asians as opposed to 31.5 (27.2–36.3, 95% C.I) and 10.7 (8.3–13.6, 95% C.I) per 100,000 person years respectively for white patients. 31 Furthermore, this study also showed higher odds of severe anaphylaxis amongst patients <16 years old (2.37 [1.83–2.90)]. It also demonstrated that if you were from a non‐white population you were less likely to be referred to allergy clinic after an episode. Fatal anaphylaxis to food, medication and unspecified allergens in the USA were associated with African Americans and older age groups, and the incidence rate of fatal food anaphylaxis in African American males increased from 0.06 in 1999–2001 to 0.21 per million in 2008–2010. 32 Asthma is an independent risk factor for anaphylaxis, and uncontrolled asthma in food allergy puts patients at an enhanced risk of severe anaphylaxis. 33 , 34 This is particularly relevant in ethnic minority groups as prevalence of asthma is significantly greater and a large proportion of cases are uncontrolled.

2.3. Atopic dermatitis

Studies have demonstrated that African American children have an increased risk of developing atopic dermatitis (AD) that the presentation varies dependent on skin colour, and that current scoring mechanisms will underestimate the severity of AD in black skin. 35 , 36 , 37 The prevalence, persistence, severity and impact on health‐related quality of life of AD is greater amongst Black American patients and those from urban areas. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 The US‐based studies have found that black children were less likely to see an outpatient provider for AD, but when they did they required more intensive treatment. 42 In addition, non‐Hispanic black children and Hispanic children were more likely to have missed days of school, compared with non‐Hispanic white children, because of AD, which can affect learning and attainment and further impact on the cycle of deprivation. 43 Filaggrin mutations are less frequent amongst Black patients. Also, there may be differences in Staphylococcus aureus colonization in skin between different ethnic groups. Some differences in phenotypes have also been described 44 , 45 , 46 ; Black patients present with extensor dermatitis as opposed to flexural involvement, erythema may not be well delineated in black skin, and other differences have also been described, including peri‐follicular involvement, palmar hyper‐linearity, peri‐ocular dark circles and diffuse xerosis. It is important that these points are embedded into medical education to raise awareness amongst healthcare professional delivering allergy care. 44 , 45

3. FACTORS INFLUENCING OUTCOMES

Poorer clinical outcomes, such as those described above, are likely to result from a myriad of factors (Figure 1), with the literature documenting that access, treatment and outcomes vary by ethnicity. Canino et al state that asthma disparities have multiple, complex and interrelated sources including patient beliefs, health literacy and financial barriers to disease management. 47 However, even before patient‐level factors have been considered, ethnic minority groups are often disadvantaged with regards to healthcare access and healthcare interactions, factors not unique to allergic disease. That said, socio‐demographic variables might influence the diagnosis and management of allergic airways diseases. A US study involving 275 children with no clinical and family history of allergic disease showed a two‐fold greater risk of sensitization to one or more aero‐allergens in African American children. 48 Another reported that the risk of sensitization to cockroach was several‐fold greater (OR – 16.4 [4.8–55.9]) in African American children. The same study also showed a significantly higher risk of cockroach sensitization in children resident in urban locations (OR – 4.0 [4.0–10.7]) and that the risk was significantly greater in those living in deprived geographical locations (OR – 11.9 [4.3–40.8]). 49 There is also evidence regarding under‐recognition and delayed diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in African American patients. 9 This has important implications not only with respect to health‐related quality of life but also on the long‐term management of asthma, as allergic rhinitis is the most frequent co‐morbidity in asthma.

FIGURE 1.

Factors to target to improve ethnicity‐based outcomes in allergic disease

Similar observations have been reported by Asthma UK. There was a strong correlation between emergency room admissions and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) average score as per the 2016–17 data set. 50 The analysis of fatal asthma as per age and IMD quintile showed higher rates in men between 45–74 years and >75 years from the most deprived areas. Those from disadvantaged socio‐economic groups are more likely to be exposed to asthma environmental triggers such as allergens, cigarette smoke and air pollution. There is a significant variation in access to basic asthma care across geographical locations, age groups and ethnicity. The main causes of deaths identified in the National Review of Asthma Deaths were over reliance on short acting beta‐agonists and underuse of inhaled corticosteroids. This was driven by lack of provision of asthma self‐management plans, and poor patient knowledge and understanding of asthma and its associated risk. The Asthma UK report suggests suboptimal basic asthma care across the country. 50 Furthermore, in the United States, after adjusting for other patient characteristics, black patients with asthma were less likely to see an outpatient physician than white patients, 51 whilst others have shown healthcare utilization related to food allergy varies by ethnicity. 52 There is also evidence that black and Puerto‐Rican children were absent from school more often because of asthma compared with white and Mexican children. 53 , 54 Moreover, the Yorkshire‐based Itchy, Sneezy and Wheezy project reported delays in referral of South Asian children to specialist allergy clinic compared with white children. 55

Once within the healthcare system pathway, several further barriers become evident. Key barriers in UK‐specific studies include under‐diagnosis and reporting of asthma, lower prescription and lower use of beta‐agonists and inhaled corticosteroids, which may partly contribute to greater healthcare utilization. 56 , 57 , 58 One factor which has been highlighted as contributing to under‐reporting and impact on prevalence of asthma is the misidentification of symptoms amongst South Asians and those from deprived backgrounds, leading to an underestimation of wheeze. 59 Under‐reporting of asthma and wheeze may also be explained by poor or suboptimal local language proficiency of parents, with one study showing that participants requiring translation reported half the levels of asthma and wheeze compared with those parents who could respond in English. 60 Factors at the individual‐level contributing to underuse of medication included beliefs that medication would cause more harm than good and a reluctance to disclose their child's asthma status. 61 Furthermore, stigma of respiratory illness specifically related to erroneous beliefs about contagiousness of asthma were found to be present within Bangladeshi participants, but not amongst those who have migrated, thought to be as a result of acculturation. 62

In a systematic review involving 25,755 children in 15 studies (2 in Pakistan, 5 in India and 8 in the UK), Lakhanpaul et al investigated facilitators and barriers in asthma care. 56 The authors make a strong case to differentiate ethnicity‐based barriers to those that relate to minority ethnic group position per se at a population‐level (e.g. language‐related). As mirrored in the adult data, uncontrolled asthma in South Asian children has been linked to multiple ethnicity‐based barriers involving South Asian families, including denial regarding diagnosis, poor concordance, stigmatization regarding use of inhalers, self‐beliefs that asthma is a contagious disease and overreliance on emergency management in hospital rather than preventive therapy via primary care.

It is clear that ethnicity is confounded with social status, and that it can be difficult to determine the independent effects of each. Social and financial hardships, combined with management and environmental factors, explain much of the observed disparity in asthma‐related re‐admissions between black and white children in the United States. 63 This is consistent with the notion that disparities arise from structural racism and social adversity. Those patients with more information, influence, resources and social networks may take more advantage of new technology and scientific development, 64 which may further increase health disparities generally, a theory consistent with the Minority Stress Model. 65 Non‐adherence to national asthma guidelines has been associated with patient's ethnicity 66 which would have exacerbated ethnic disparities in a vicious cycle. There is evidence of lesser adherence to controller medication amongst ethnic minority groups with particular risk factors including race, education, income, baseline symptoms and attitude. 67 Further evidence of lower adherence to prescription receipt, prescription initiation and medication use amongst ethnic minority groups has been reported, with medication beliefs and depressive symptoms acting as barriers, which may in part serve to reinforce the implicit bias of healthcare professionals to under‐prescribe beta‐agonists and inhaled corticosteroids if they believe their patients will not use them. 68

4. WHAT CAN WE DO TO THESE REDUCE INEQUALITIES?

Some of the structural factors identified above (e.g. under‐diagnosis and low prescription rates) may reflect a lack of cultural competence which requires improved training and communication skills of healthcare professionals. The impact of institutional or systemic patterns of racism upon many allergic conditions is noted by Davis, and cultural competency training to combat these barriers and reduce implicit bias is advocated. 1 That said, there is a paucity of high‐quality research showing a positive relationship between cultural competency training and improved patient outcomes which needs to be addressed by clearer descriptions and replicability of training curricula. 69

The need for improved communication and education between health professionals and patients is evident from the factors stated above. In a qualitative study involving interviews with South Asian British mothers of children <5 years with food allergies, Peckover et al highlighted the need to raise awareness and improve knowledge amongst the South Asian community regarding allergies, as mothers sought help from family and friends as their first port of call regarding their child's health. 55 Within anaphylaxis, several ‘Prevention of Future Death Reports’ highlight the fact that healthcare professionals should emphasize and ensure understanding for the requirement of adrenaline auto‐injectors to be carried at all times by patients and families.

The lack of diversity in research remains problematic with clinical trials failing to recruit a representative population, meaning new interventions may not be generalizable to certain ethnic minority groups. Again, this issue is not unique to allergic disease with relatively few clinical trials reporting complete ethnicity‐related data. 70 That said, the challenges of recruiting to ethnic minority groups to asthma studies have been distilled to four key issues: patients where there are competing demands and inaccurate beliefs about diagnosis, institutions which have policies restricting incentives, research teams where staff training is needed, and interventions which may be unappealing or inconvenient to some. 71 Also, the translation of patient‐facing materials carry significant cost implications; however, the cost of not doing this proactively can be seen throughout this paper Or article. One further barrier could be the need to balance scientific rigour with pragmatism as highlighted by Abrams, who suggests there is little focus on pragmatic research which permits variation in therapy to suit different ethnic groups. 72 A way forward is to have proportionate representation of ethnic minority groups in clinical trials and translational research. However, sample size and heterogeneity would still not allow for meaningful sub‐analysis to be conducted. Standardization of international nomenclature with respect to ethnicity might create opportunities for systematic reviews and meta‐analysis. At present, national and international guidelines for allergic diseases are largely based on data generated from white population, thus not addressing disparities related to genetics and ethnicity.

5. LEARNING FROM RESEARCH FROM OTHER NON‐COMMUNICABLE DISEASES

As evidenced above, the importance of providing tailored health education (to both patients and healthcare professionals) is required on a number of levels (Figure 1). Existing theoretical models in health education have been criticized for emphasizing individual cognitive process without giving much attention to the embedment of cultural contexts and social structures in human behaviour. 73 Indeed, a recent systematic review found few theory‐based asthma self‐management interventions for South Asians and African Americans. 74 The importance of culture as a factor in health and health behaviours has been increasingly recognized, including its potential role in enhancing health messaging and interventions. The cultural characteristics of a group may have a direct or indirect relationship with health‐related priorities and decision‐making, as well as receptivity and adoption of health messages and interventions. 75 It is therefore important that health programmes and interventions are culturally tailored not only to improve acceptance but also salience of health communication. Cultural tailoring of health information involves recognizing and reinforcing cultural values, beliefs, norms and practices of a group, and developing health messages based on these to provide context and meaning to the message. 76

Community‐based culturally tailored interventions have been reported to be acceptable, feasible and effective in improving the management of various chronic conditions including cardiovascular disease and diabetes. 77 , 78 A recent systematic review suggests that interventions incorporating surface structure (tailoring intervention to observable characteristics of the target group) and deep structure (acknowledging the cultural, social, historical, environmental and psychological context of the target group that influences the health behaviour) are successful in improving disease awareness, healthcare access and self‐management. 75 , 79 The review highlights that, in addition to linguistically relevant materials, integration of deep structural components is key to intervention success. It suggests that awareness of fundamental philosophies of chronic disease self‐management, cultural practice of the target group, and involvement of families are important factors in intervention effectiveness. This was further emphasized in another review which recommends the provision of social support (deep structure) via linguistically and ethnically matched healthcare professionals, peers and family members as the most effective cultural component of the intervention in chronic disease. 80 Identifying and measuring the cultural context of risks and resilience that influence disease is key to designing and evaluating culturally adapted interventions. Although surface variables (matching ethnicity and language) are important, cultural adaptations should focus on factors such as cultural norms, traditions and values that impact the intervention effectiveness. 81

The use of culturally tailored interventions is increasing in community and healthcare settings, but clear and pragmatic guidelines for (co‐)developing, implementing and evaluating these interventions are lacking. 82 In the current context of widening health disparities, strategic focus is required towards adopting culturally relevant programmes and practices to improve quality of care and promote health equity.

6. WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE IN ALLERGIC DISEASE?

6.1. Service delivery aspects

To address the disparities above, several immediate and long‐term changes requiring a concerted effort from all stakeholders will need to be implemented. We need an ethnically diverse multi‐disciplinary workforce to build trust with communities and offer services that are accessible. 83 , 84 This is in keeping with recent results from the NHS staff survey. Inclusion of ethnicity‐based disparities in allergic disease within healthcare professional curricula and continuing professional development is imperative. This is to raise awareness not only of phenotypic differences in allergic disease, but also to identify, model and cultivate attitudes, behaviour and appropriate communication skills, that can help eliminate, rather than exacerbate, health and health care disparities. 85 Inclusion of these disparities will enable a cultural transformation within health services to address systemic and structural racism and implicit bias. The need for healthcare professionals to acknowledge diversity within ethnic minority groups is required, with awareness that common cultural patterns may exist. Effective communication with diverse patient groups will be facilitated by the provision of accessible tools and resources, not least the availability of patient‐facing materials which are appropriate for different literacy levels, languages and cultures, given that these factors intersect and compound, leading to poorer clinical outcomes. Through consultation with patients and patient organizations and examination of ‘Prevention of Future Death Reports’, the need for materials which address perceptions of severity, vulnerability and stigma within the ethnic minority population are required, whilst also considering ways to empower patients (and their carers) to challenge healthcare professionals when it comes to appropriate prescriptions of emergency medication and referral to specialists.

6.2. Research initiatives

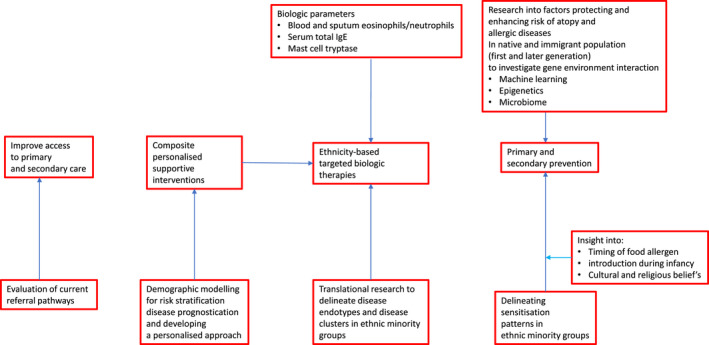

Further research involving (a) UK‐based samples, (b) multi‐disciplinary expertise, (c) food‐allergy populations and (d) underrepresented ethnicities (e.g. Arabic and Chinese) is desperately needed, given that the majority of research included in this comprehensive review has been taken from asthma populations and North America studies. The latter being important given the differences in the US healthcare system (especially lack of access to care in respect to insurance coverage and ease of access to clinical facilities in underserved neighbourhoods) and lack of universal health care compared with the UK. There are a number of unanswered questions relating to epidemiology (e.g. what is the true prevalence of food allergy in ethnic minority groups within HIC and the UK specifically?) and phenotypes (e.g. is uncontrolled asthma in ethnic minority groups directly attributable to an individual's social context or is the disease intrinsically more severe?), in addition to those more behavioural in nature (e.g. how might cultural and religious practises impact on help‐seeking and referral pathways within ethnic minority groups as well as identifying the barriers and facilitators to effective self‐management?) (Table 2). The answers to these questions are likely to result in the development of composite supportive interventions which may be tailored to individuals based on their demographics and social context. It is likely that in time, artificial intelligence, in particular machine learning, will enable us to improve our ability to match interventions to particular subgroups. One hurdle which must be overcome in order to pave the way for these developments are a greater and proportionate representation of ethnic minority groups within clinical research. An integrated approach and strategy to improve clinical outcomes in allergic diseases is summarized in Figure 2.

TABLE 2.

Evidence gaps and key research questions for addressing ethnicity‐based disparities in allergic diseases

| Epidemiology |

|

| Phenotypes |

|

| Sensitization |

|

| Care pathways |

|

| Behavioural |

|

FIGURE 2.

Integrated approach to improve clinical outcomes in allergic diseases in ethnic minority groups

7. CONCLUSION

It is clear from the published evidence that ethnicity‐based disparities in allergic disease exist and the problem is likely to be underestimated due to the factors and unanswered questions highlighted. Non‐white populations are an afterthought in research which has to change. Most research comes from outside of the UK and/or relates to asthma; proportionate representation of ethnic minority population in clinical trials and genome datasets, with translational research is desperately needed. There is encouraging research from other non‐communicable diseases that provision of tailored health education involving both surface structure (e.g. observable characteristics of ethnic minority) and deep structure (e.g. cultural, social, historical, environmental and psychological context of ethnic minority) are successful in improving disease awareness, healthcare access and self‐management. We therefore must involve community partners in designing disease prevention/ management plans, as well as in research more generally. Development, implementation and evaluation of cultural competency training is required for healthcare professionals, as are targeted biologic therapies for patients. A concerted effort from multi‐disciplinary experts will be required to address these disparities on a holistic scale.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

MTK is Chair of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Working Group of BSACI. His department has received educational grants from ALK Abello, Allergy Therapeutics, MEDA and other pharma companies. MTK has received grants for work unrelated to this manuscript from NIHR, MRC CiC, FSA and GCRF. NM is Chair of the Paediatric Allergy Committee of BSACI. He has received educational grants (honoraria for educational lectures/attendance at allergy meetings) from ALK Abello, Nutricia, Abbott and Nestle. All other authors declare they have no relevant conflict of interest in relation to this publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jones and Krishna conceptualized the structured of the review. Jones, Krishna, Paudyal, West, Mansur, Jay and Makwana identified relevant literature for inclusion and contributed to original draft. All authors contributed to critical review of the manuscript, with relevant edits and expert opinion from specialist perspective. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Jones CJ, Paudyal P, West RM, et al. Burden of allergic disease among ethnic minority groups in high‐income countries. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52:604–615. doi: 10.1111/cea.14131

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data on which the manuscript is based on are presented within text and tables and appropriately referenced.

REFERENCES

- 1. Davis CM, Apter AJ, Casillas A, et al. Health disparities in allergic and immunologic conditions in racial and ethnic underserved populations: a Work Group Report of the AAAAI Committee on the Underserved. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(5):1579‐1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morris M, Woods LM, Rachet B. A novel ecological methodology for constructing ethnic‐majority life tables in the absence of individual ethnicity information. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:361‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Subramanian A, Adderley NJ, Gkoutos GV, Gokhale KM, Nirantharakumar K, Krishna MT. Ethnicity‐based differences in the incident risk of allergic diseases and autoimmune disorders: a UK‐based retrospective cohort study of 4.4 million participants. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51(1):144‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krishna MT, Subramanian A, Adderley NJ, Zemedikun DT, Gkoutos GV, Nirantharakumar K. Allergic diseases and long‐term risk of autoimmune disorders: longitudinal cohort study and cluster analysis. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(5):1900476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351(9111):1225‐1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rudan I, Sidhu S, Papana A, et al. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic review and analysis. J Glob Health. 2015;5(1):010409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Everhart RS, Kopel SJ, Esteban CA, et al. Allergic rhinitis quality of life in urban children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:365‐370.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pembrey L, Waiblinger D, Griffiths P, Wright J. Age at cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus and varicella zoster virus infection and risk of atopy: the Born in Bradford cohort, UK. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(6):604‐613. doi: 10.1111/pai.13093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):1‐7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2017 Archived national asthma data. Accessed November 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/archivedata/2017/2017_archived_national_data.html

- 11. Busby J, Heaney LG, Brown T, et al. Ethnic differences in severe asthma clinical care and outcomes: an analysis of United Kingdom primary and specialist care. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(2):495‐505.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Busby J, Matthews JG, Chaudhuri R, et al. Factors affecting adherence with treatment advice in a clinical trial of patients with severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2021;2100768. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00768-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wohlford EM, Huang PF, Elhawary JR, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in eligibility for asthma biologics among pediatric populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1324‐1331.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Identifying infants at high risk of peanut allergy: The Learning Early About Peanut Leap (LEAP) screening study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:135‐143.e1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomised trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803‐813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perkin M, Bahnson HT, Logan K, et al. Factors influencing adherence in a trial of early introduction of allergenic food. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1595‐1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e185630. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. The Public Health Impact of Parent‐Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181235. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mahdavinia M, Fox SR, Smith BM, et al. Racial differences in food allergy phenotype and health care utilization among US children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):352‐357.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johns CB, Savage JH. Access to health care and food in children with food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):582‐585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y, Allen KJ, Suaini NHA, Peters RL, Ponsonby AL, Koplin JJ. Asian children living in Australia have a different profile of allergy and anaphylaxis than Australian‐born children: a state‐wide survey. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48(10):1317‐1324. doi: 10.1111/cea.13235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Acker WW, Plasek JM, Blumenthal KG, et al. Prevalence of food allergies and intolerances documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(6):1587‐1591.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sicherer SH, Muñoz‐Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the United States determined by means of a random digit dial telephone survey: a 5‐year follow‐up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6):1203‐1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sicherer SH, Muñoz‐Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA. US prevalence of self‐reported peanut, tree nut, and sesame allergy: 11‐year follow‐up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1322‐1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sicherer SH, Muñoz‐Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of seafood allergy in the United States determined by a random telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(1):159‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Botha M, Basera W, Facey‐Thomas HE, et al. Rural and urban food allergy prevalence from the South African Food Allergy (SAFFA) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):662‐668.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dias RP, Summerfield A, Khakoo GA. Food hypersensitivity among Caucasian and non‐Caucasian children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(1):86‐89. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fox AT, Kaymakcalan H, Perkin M, du Toit G, Lack G. Changes in peanut allergy prevalence in different ethnic groups in 2 time periods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):580‐582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vincent E, Bilaver LA, Fierstein JL, et al. Associations of Food Allergy‐Related Dietary Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors among caregivers of Black and White children with food allergy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(4):797‐810. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2021.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brewer AG, Jiang J, Warren CM, et al. Racial differences in timing of food allergen introduction. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(1):329‐332.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buka RJ, Crossman RJ, Melchior CL, et al. Anaphylaxis and ethnicity: higher incidence in British South Asians. Allergy. 2015;70(12):1580‐1587. doi: 10.1111/all.12702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jerschow E, Lin RY, Scaperotti MM, McGinn AP. Fatal anaphylaxis in the United States, 1999–2010: temporal patterns and demographic associations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(6):1318‐1328.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pumphrey R. Anaphylaxis: can we tell who is at risk of a fatal reaction? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):285‐290. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000136762.89313.0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30(8):1144‐1150. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00864.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williams HC, Pembroke AC, Forsdyke H, Boodoo G, Hay RJ, Burney PG. London‐born black Caribbean children are at increased risk of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2 Pt 1):212‐217. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90128-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ben‐Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(5):920‐925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, Yosipovitch G. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(4):395‐402. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01740.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boguniewicz M, Alexis A, Beck L, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1519‐1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Silverberg J, Simpson E. Association between severe eczema in children and multiple comorbid conditions and increased healthcare utilization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:476‐486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Silverberg J, Hanifin J. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population‐based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1132‐1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hirano S, Murray S, Harvey V. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749‐755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fischer AH, Shin DB, Margolis DJ, Takeshita J. Racial and ethnic differences in health care utilization for childhood eczema: an analysis of the 2001–2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(6):1060‐1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wan J, Margolis DJ, Mitra N, Hoffstad OJ, Takeshita J. Racial and ethnic differences in atopic dermatitis‐related school absences among US children. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(8):973‐975. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buster K, Stevens E, Elmets C. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53‐59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaufman B, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis A. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stevenson MD, Sellins S, Grube E, et al. Aeroallergen sensitization in healthy children: racial and socioeconomic correlates. J Pediatr. 2007;151(2):187‐191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sarpong SB, Hamilton RG, Eggleston PA, Adkinson NF Jr. Socioeconomic status and race as risk factors for cockroach allergen exposure and sensitization in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97(6):1393‐1401. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70209-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Margolis D, Apter A, Gupta J, et al. The persistence of atopic dermatitis and filaggrin (FLG) mutations in a US longitudinal cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:912‐917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Asthma UK. On the edge: How inequality affects people with asthma. Accessed November 20, 2021. https://www.asthma.org.uk/dd78d558/globalassets/get‐involved/external‐affairs‐campaigns/publications/health‐inequality/auk‐health‐inequalities‐final.pdf.

- 50. Canino G, McQuaid EL, Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6):1209‐1217; quiz 1218‐9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fitzpatrick AM, Gillespie SE, Mauger DT, et al. Racial disparities in asthma‐related health care use in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2052‐2061. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e9‐17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Findley S, Lawler K, Bindra M, Maggio L, Penachio MM, Maylahn C. Elevated asthma and indoor environmental exposures among Puerto Rican children of East Harlem. J Asthma. 2003;40(5):557‐569. doi: 10.1081/jas-120019028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kattan M, Mitchell H, Eggleston P, et al. Characteristics of inner‐city children with asthma: the National Cooperative Inner‐City Asthma Study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;24(4):253‐262. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Peckover S, Jay N, Chowbey P, Rehman N, Javed F. British South Asian mothers’ experiences of seeking help for their food allergic child. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51(7):951‐954. doi: 10.1111/cea.13875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lakhanpaul M, Bird D, Manikam L, et al. A systematic review of explanatory factors of barriers and facilitators to improving asthma management in South Asian children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Duran‐Tauleria E, Rona RJ, Chinn S, Burney P. Influence of ethnic group on asthma treatment in children in 1990‐1: national cross sectional study. BMJ 1996;313:148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7050.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kuehni CE, Strippol MPF, Low N, Brooke AM, Silverman M. Wheeze and asthma prevalence and related health‐service use in white and south Asian pre‐schoolchildren in the United Kingdom. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1738‐1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Michel G, Silverman M. Strippoli M‐PF, et al. Parental understanding of wheeze and its impact on asthma prevalence estimates. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(6):1124‐1130. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00008406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Panico L, Bartley M, Marmot M, Nazroo J, Sacker A, Kelly Y. Ethnic variation in childhood asthma and wheezing illnesses: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):1093‐1102. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Smeeton NC, Rona RJ, Gregory J, et al. Parental attitudes towards the management of asthma in ethnic minorities. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1082‐1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cane R, Pao C, McKenzie S. Understanding childhood asthma in focus groups: perspectives from mothers of different ethnic backgrounds. BMC Fam Pract. 2001;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mersha TB, et al. Genetic ancestry differences in pediatric asthma readmission are mediated by socioenvironmental factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1210‐1218.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mechanic D. Policy challenges in addressing racial disparities and improving population health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):335‐338. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674‐697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ortega AN, Gergen PJ, Paltiel AD, Bauchner H, Belanger KD, Leaderer BP. Impact of site of care, race, and Hispanic ethnicity on medication use for childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Apter AJ, Boston RC, George M, et al. Modifiable barriers to adherence to inhaled steroids among adults with asthma: it's not just black and white. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(6):1219‐1226. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McQuaid EL. Barriers to medication adherence in asthma: the importance of culture and context. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(1):37‐42. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lie DA, Lee‐Rey E, Gomez A, et al. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:317‐325. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Corbie‐Smith G, St George DM, Moody‐Ayers S, Ransohoff DF. Adequacy of reporting race/ethnicity in clinical trials in areas of health disparities. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(5):416‐420. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kramer CB, LeRoy L, Donahue S, et al. Enrolling African‐American and Latino patients with asthma in comparative effectiveness research: lessons learned from 8 patient‐centered studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1600‐1607. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Abrams EM, Shaker M, Oppenheimer J, Davis RS, Bukstein DA, Greenhawt M. The challenges and opportunities for shared decision making highlighted by COVID‐19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8):2474‐2480.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Krumeich A, Weijts W, Reddy P, Meijer‐Weitz A. The benefits of anthropological approaches for health promotion research and practice. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:121‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ahmed S, Pinnock H, Steed E. Developing theory‐based asthma self‐management interventions for South Asians and African Americans: a systematic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(4):1040‐1068. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:439‐455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Resnicow K, Braithwaite RL, Glanz K. Applying theory to culturally diverse and unique populations. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey‐Bass; 2002:485‐509. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Williams I, Utz S, Hinton I, et al. Enhancing diabetes self‐care among rural African Americans with diabetes: results of a two‐year culturally tailored intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40:231‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Vincent D, McEwen MM, Hepworth JT, et al. The effects of a community‐based, culturally tailored diabetes prevention intervention for high‐risk adults of Mexican descent. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40:202‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Huang YC, Garcia AA. Culturally‐tailored interventions for chronic disease self‐management among Chinese Americans: a systematic review. Ethn Health. 2018;1:20. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1432752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Heo HH, Braun KL. Culturally tailored interventions of chronic disease targeting Korean Americans: a systematic review. Ethn Health. 2014;19(1):64‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hall GN, Ibaraki AY, Huang ER, et al. A meta‐analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behav Ther. 2016;47:993‐1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Joo JY, Liu MF. Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: a scoping review. Nursing Open. 2021;8(5):2078‐2090. doi: 10.1002/nop2.733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. National Health Service . Equality, diversity and health inequalities: The challenge and the evidence. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality‐hub/equality‐standard/the‐challenge/

- 84. West M, Dawson J. NHS Staff Management and Health Service Quality. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215454/dh_129658.pdf

- 85. Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:654‐665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Health Interview Survey 2017–2019. Most Recent National Asthma Data; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. Accessed November 20, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data on which the manuscript is based on are presented within text and tables and appropriately referenced.