Abstract

Black youth experience racial discrimination at higher rates than other racial/ethnic groups in the United States. To identify how racism can simultaneously serve as a risk factor for adverse childhood experience (ACE) exposure, a discrete type of ACE, and a post‐ACE mental health risk factor among Black youth, Bernard and colleagues (2021) proposed the culturally informed ACEs (C‐ACE) model. While an important addition to the literature, the C‐ACE model is framed around a single axis of race‐based oppression. This paper extends the model by incorporating an intersectional and ecodevelopmental lens that elucidates how gendered racism framed by historical trauma, as well as gender‐based socialization experiences, may have implications for negative mental health outcomes among Black youth. Clinical and research implications are discussed.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, racial trauma, racism, intersectionality, gendered racism

The frequency, nature, and impact of racism on Black youth likely differ across genders and contexts (Assari et al., 2017; Hughes, Watford, et al., 2016), underscoring the need for an intersectional‐contextual framework to understanding racism and trauma. An intersectional‐contextual lens recognizes that racism (unequal system of power that privileges white people and oppresses Black people) interacts with other types of oppression like sexism (social system that creates gender inequality; Collins, 2000). This interaction gives rise to unique manifestations of racism along gendered lines (Collins, 2000; Crenshaw, 1991) that also varies within and across contexts (Hughes, Watford, et al., 2016; Saleem et al., 2020). Theoretical models of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which are negative life events that put children at risk for a range of poor life outcomes including trauma (Herzog & Schmahl, 2018), have largely neglected stressors uniquely affecting Black youth, such as racism, and often fail to consider the role of context across development. Recent theories such as the culturally informed ACEs model (C‐ACEs) have sought to address this gap by incorporating a focus on racism into thinking about ACEs (Bernard et al., 2021). The C‐ACE model extends our understanding of the traumatic effects of racism on Black youths’ mental health by identifying racism as an ACE, as well as a factor that puts Black youth at risk for other ACEs, and poor post‐ACE outcomes (Bernard et al., 2021). While the C‐ACE model is decontextualized, the Developmental and Ecological Model of Youth Racial Trauma (DEMYth‐RT) explicitly focuses on how ecological contexts are both sources of risk for and coping with ACEs (Saleem et al., 2020), the latter of which is rare among trauma‐focused theoretical models. Nevertheless, a major limitation of both models is a focus on a single axis of oppression (i.e., racism), neglecting other systems of oppression affecting Black youth, such as sexism.

Much of the literature on Black youths experiences of racism has focused on interpersonal experiences of differential treatment by race (i.e., racial discrimination, microaggressions). This research shows that Black youth experience racial discrimination at significantly higher rates than any other ethnic‐racial minority group in the United States (U.S.) (Pachter & Coll, 2009), averaging five discrimination experiences per day (English et al., 2020). The frequency of racial discrimination exposure can vary across contexts (e.g., school, neighborhoods), time, and perpetrator (teachers vs. peers; Greene et al., 2006; Hughes, Del Toro, et al., 2016), and these experiences are associated with poorer mental health including elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Benner et al., 2018; Galán et al., 2021; Loyd et al., 2019). More recently, scholars have suggested that the enduring, pervasive effects of racial discrimination can lead to trauma symptoms (e.g., intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance; Carter, 2007; Heard‐Garris et al., 2018), coining the term “racial trauma” (Comas‐Díaz et al., 2019). A growing body of research primarily among Black adults shows that racism is gendered (e.g., Williams & Lewis, 2019). Gendered racism describes unique forms of racism by gender and heightened vulnerability across contexts (e.g., Black girls and sexual violence; Essed, 1991). To truly examine and respond to the gendered and contextual nature of mental health vulnerabilities among Black adolescents, research needs to examine the historical and contemporary experiences of racism that shape Black adolescents’ mental health across different contexts. This article takes an intersectional‐contextual perspective on racism by drawing on classic theories and contemporary trauma models to review the literature on gendered racism during key developmental contexts for Black adolescents. Taking a strengths‐based approach, we also focus on cultural coping mechanisms that may facilitate better mental health outcomes for Black adolescent boys and girls.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In this review, we draw from contemporary trauma‐focused theories (C‐ACEs, DEMYth‐RT) and classic frameworks (intersectionality, ecodevelopmental) to advance an intersectional‐contextual approach to understanding the gendered nature of racism as an adverse childhood event across contexts. First, we draw on the C‐ACE model, a trauma‐focused model that extends the ACE framework by positing that racism (1) increases Black youths’ exposure to potentially traumatic events (e.g., involvement with juvenile justice system); (2) is a distinct ACE category through cultural (e.g., dehumanizing stereotypes), interpersonal (e.g., racial discrimination), and institutional (e.g., disproportionality in school discipline outcomes) mechanisms, and; (3) influences post‐ACE mental health outcomes for Black youth (Bernard et al., 2021). In this review, we focus on the parts of the model that link historical trauma to contemporary racist social conditions, laying the groundwork for racism as a distinct ACE for Black youth. We also draw on intersectionality, which suggests that economic, political, and ideological oppression vary along racial and gendered lines to suggest that racism as an ACE may vary by gender (Crenshaw, 1991). Accordingly, Black girls and boys likely have distinct experiences of racism because of different gendered racial stereotypes (e.g., Black boys stereotyped as dangerous, violent, criminal; Black girls stereotyped as sexually promiscuous, lascivious, and servile; Collins, 2000).

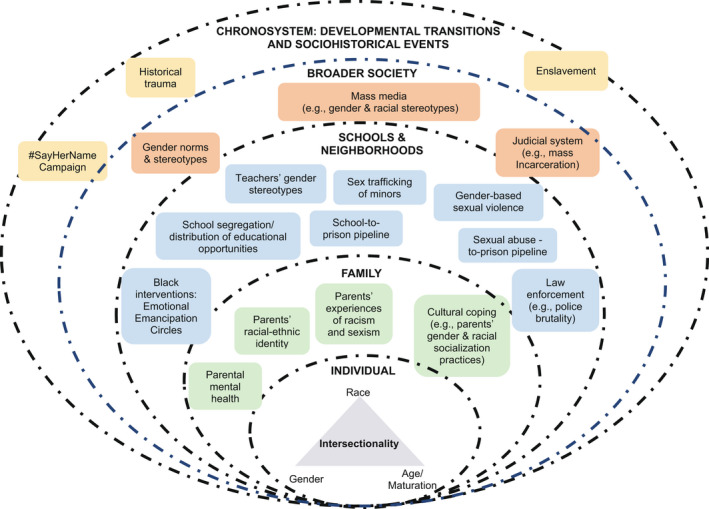

To this intersectional lens, we apply a contextual approach, which is common in the trauma literature. For instance, DEMYth‐RT posits that chronic exposure to racism (e.g., institutional, interpersonal) can put youth at risk for racial trauma but social and cultural assets can facilitate coping with racial trauma (Saleem et al., 2020). Here, we draw specifically on the ecodevelopmental framework, which blends a focus on context with a focus on risk and protective factors embedded in youths’ environments that shape their mental health outcomes over time (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). This framework draws on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model to propose that youth are embedded in multiple, interacting environments, such as the macrosystem (context comprising of cultural ideologies) and microsystem (direct interactions with youth in home, school, and neighborhood contexts; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). Accordingly, gendered racial stereotypes are part of the macrosystem context that may drive institutional and interpersonal racism (risk factors) over time and in contexts like schools, the juvenile justice system, and neighborhoods (see Figure 1). In this article, we focus on these key contexts because of their increasing salience in adolescence. As youth get older, the stakes of poor school outcomes become higher, they are viewed and treated more like adults, and they spend more unmonitored time in their neighborhoods (Bucci et al., 2021; Ingoldsby & Shaw, 2002), which heightens their vulnerability to risks such as police violence and sex trafficking.

Figure 1.

An intersectional‐contextual approach to racial trauma exposure risk and coping among Black youth.

Cultural Coping: Gendered Racial Socialization

Racism may also spur Black families to engage in cultural coping strategies such as racial socialization in the family microsystem context, which is protective against the negative effects of racism (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019; Hughes et al., 2006; Umaña‐Taylor & Hill, 2020). Parent racial socialization is a multifaceted parenting practice that involves instilling racial and cultural pride in youth and preparing youth for potential racial bias (Hughes et al., 2006). There is evidence that parents engage in gendered racial socialization in recognition of the unique vulnerabilities faced by Black boys and girls (e.g., Peck et al., 2014). Critically, there is evidence that racial socialization can buffer the detrimental effects of racial discrimination on youth psychological adjustment (Hughes et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2020). As such, we focus on parents’ use of gendered racial socialization to help Black boys and girls cope with gendered racial discrimination in school, justice, and neighborhood contexts.

CHRONOSYSTEM: HISTORICAL TRAUMA ALONG GENDERED LINES

Historical trauma refers to the idea that collective tragedies throughout history can imprint themselves into the cultural memory of a particular group (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998), and these historical experiences of trauma likely manifested differently for Black men and women in the U.S. (e.g., Brave Heart, 1999). It is important to understand the impact of historical trauma because it has deleterious effects on Black people’s psychological health through myriad pathways (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Gone, 2013; Gump, 2010). For instance, when historical injustices (e.g., enslavement; part of the chronosystem context) are reflected upon, these reflections can increase the risk for mental health problems long after those events have passed and among people that never experienced the events themselves (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998). Moreover, historical injustices can affect the contemporary experiences of Black people through the intergenerational transmission of stress and systemic contexts that continue to oppress them (Gone, 2013; Gump, 2010). Society must consider the complexities of historical trauma in order to redress them and ensure their effects do not persist in future generations (National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, 2021).

The transatlantic slave trade is a historical trauma that was undergirded by scientific racism and has informed how Black boys and girls are treated in the U.S. Scientific racism and racial capitalism dehumanized people from Africa, racializing them as Black and intellectually inferior, devaluing and erasing their culture, and treating them as objects to create capital, and as capital themselves (Ani, 1981; da Silva, 2020; Nobles, 1978; Spillers, 1987; Smedley & Smedley, 2005; Wilderson, 2009). Racist experiences during enslavement varied by gender. For Black women and girls, sexual and reproductive acts of violence were a common occurrence during enslavement (Johnson, 2020). For instance, Black women and girls were routinely subject to nude physical examinations during public auctions to assess their reproductive ability and those who were considered “strong” were then raped to birth more children into slavery for economic profit (Bridgewater, 2005). Young black girls were also encouraged to have sex as preparation for their later status as breeders (Bridgewater, 2005). The erasure of Black girlhood and equating Black women’s worth with their sexual and reproductive abilities shaped the opportunities and treatment of Black women and girls whether enslaved or “free” within the U.S.’s slave‐based economy (Johnson, 2020).

During slavery, Black men and boys experienced different types of violence because they were characterized as prone to physical and sexual violence and therefore needed to be enslaved to protect white people (Kendi, 2019). These stereotypes meant that Black men were subjected to severe physical punishments, which were often publicized and treated as a spectacle (Wilkerson, 2011). For instance, throughout enslavement and the Jim Crow Era, Black men were frequently lynched publicly or executed by the state for unsubstantiated accusations ranging from sexual assault to theft (Wilkerson, 2011). For example, Emmett Till, a 14‐year‐old boy, was brutally murdered in Mississippi in 1955, because he was accused of flirting with a white woman (Library of Congress, n.d.). Despite the extreme physical violence experienced by Black men, the U.S. engaged in targeted recruitment of Black men and boys to fight in every major American war (Alt et al., 2002), leveraging racist stereotypes about their physical prowess (Alt et al., 2002). Even while serving their country, Black soldiers were vulnerable to violence. During the Fort Pillow massacre, confederate soldiers slaughtered ~300 predominantly Black soldiers who had surrendered (Cimprich, 2005). Moreover, recognition for their service and provision of postwar benefits were not equally distributed for Black veterans (Alt et al., 2002), further devaluing their lives and contributions. In sum, while racism during slavery dehumanized and devalued all Black people, historical trauma was gendered: Black girls were at heightened risk of sexual and reproductive violence and Black boys were at heightened risk for physical violence. It is important to note that the recognition of heightened likelihood does not erase the very real and consistent threats of all types of violence for Black boys and girls.

CONTEMPORARY RACISM: AN INTERSECTIONAL‐CONTEXTUAL APPROACH

Historical trauma due to slavery has been carried forward in contemporary American society through ongoing racist stereotypes that undergird public policies, institutional practices, and interpersonal interactions, which manifest as gendered racism within context. However, Black parents often engage in gendered racial socialization to protect their Black boys and girls from the systemic and interpersonal experiences of racism fueled by harmful stereotypes.

Broader Society: Gendered Stereotypes of Black Girls and Boys

The stereotypes that undergirded much of the physical and sexual violence experienced by Black people during and immediately after slavery continue to operate in contemporary times (see Figure 1). Notably, the history of sexual exploitation and violence that Black women endured manifested in the Jezebel stereotype, which represents Black women and girls as inherently sexually promiscuous (Collier et al., 2017; Pilgrim, 2002). In the decades following the end of slavery, the Jezebel stereotype continued to put Black women and girls at heightened risk of being beaten and incarcerated for prostitution with no evidence and solely at the discretion of white male police officers (Hartman, 2019). These stereotypes have also led to Black girls being viewed as less innocent and more like adults compared to white girls in contemporary times and vulnerable to disproportionate rates of discipline in schools (Epstein et al., 2017; Morris, 2016).

Similarly, many scholars argue that stereotypes of Black men as violent and dangerous continue to shape how Black men and boys are treated today (Atkins‐Loria et al., 2015; Degruy‐Leary, 1984). Historically, social scientists explained Black boys’ social difficulties as due to their biology or culture (Cross, 2003), fueling stereotypes of Black boys behaviors reflecting violence and criminality (Welch, 2007). For instance, in the 1990s, the “super predator” stereotype reintroduced the myth of irredeemable and predestined Black male criminality that destroyed communities (Moriearty & Carson, 2012). This myth triggered a wave of juvenile justice reforms that resulted in the disproportionately harsh sentencing of Black boys (National Campaign to Reform State Juvenile Justice Systems, 2013). Recent research suggests that these ideas continue to prevail as Black boys are consistently seen as older, less innocent, and more dangerous than same aged, other raced peers (Goff et al., 2014). To conclude, racist gendered stereotypes in contemporary times have contributed to the erasure of Black girlhood and Black boyhood, which has directly shaped institutional policies and practices and their treatment in the school and justice systems.

Schools and Neighborhoods

The school‐to‐prison pipeline

One of the most harmful effects of contemporary gendered racist cultural stereotypes in the lives of Black youth has been its legacy in the education system through the school‐to‐prison pipeline. The school‐to‐prison pipeline describes the unintended consequences of zero tolerance school policies intended to reduce school violence by requiring schools to respond to even minor student disruptions with harsh punishments but often act as a direct pathway to the juvenile justice system (Cerrone, 1999; Christle et al., 2005; Curtis, 2014; Khalek, 2011). Because of these policies, Black boys and girls have been disproportionately disciplined in school contexts beginning as early as preschool. According to the U.S. Department of Education (2018), even though Black boys make up 7.9% of the pre‐K‐12 student population, they account for 25% of expulsions, 33.9% of school‐related arrests, and 29.4% of referrals to law enforcement under zero tolerance policies. In pre‐K‐12 schools, Black girls are the only group of girls subjected to disproportional exclusionary school discipline, at two times the rate of their current enrollment size (U.S. Department of Education, 2018). Black girls are also being channeled into the juvenile justice system via punitive, zero‐tolerance policies but their unique experiences and needs have been rendered largely invisible in this line of work (Crenshaw et al., 2015; Morris, 2016). As such, the school‐to‐prison pipeline not only affects Black boys but also harms Black girls.

Despite commonalities in the disproportionality of school discipline for Black girls and Black boys, there are unique gendered ways in which the school‐to‐prison pipeline manifests. For one, gendered racial stereotypes can lead to microaggressions, which are subtle, often unintentional verbal slights that invalidate or insult the individual because of their race and gender (Ghavami & Peplau, 2013; Sue et al., 2008). Black boys typically experience gendered racial microaggressions that are related to assumptions of inferior intellect and criminality (Sue et al., 2008). These experiences can be frustrating and enraging, leading to increases in aggressive attitudes in Black boys (Cunningham et al., 2018). Displays of aggression are rooted in gendered norms of emotional expression (Berke & Zeichner, 2016), and when aggression is displayed by Black boys, this likely reinforces stereotypes about their behavior and heightens their vulnerability to justice‐contact and being pushed out of the education system. These interpersonal and systemic contexts likely explain why 28% of Black men report never progressing further in their education than a high school diploma compared to 17% of Black women (Black Future Lab, 2019). In essence, the gendered racism and historical trauma of controlling Black boys has reproduced by effectively allowing disproportionately white educators to guide Black boys into the justice system (e.g., Grissom et al., 2009; Lindsay & Hart, 2017; Meier & Stewart, 1992).

A similar gendered‐racial process occurs for girls but is rooted in other kinds of gendered expectations for Black girls’ behavior. Recent research shows that teachers’ subjective evaluations of Black girls behaviors (e.g., compliance) are typically a precipitating factor for referral for exclusionary discipline (Gibson et al., 2019; Girvan et al., 2017). There is evidence to suggest that these discipline referrals tend to enforce white, mainstream standards of femininity, such as being compliant, passive, and quiet (Blake et al., 2011; Crenshaw et al., 2015; Morris, 2007). In one qualitative study, teachers linked loud and insolent behavior to Black girls, chastised them for being “unladylike,” and “the presumed loud and confrontational behavior of African American girls was viewed as a defect that compromised their very femininity” (Morris, 2007, p. 506). Similar stories of racialized gender policing abound in the media, with several stories of Black girls being disproportionately targeted for racist and sexist dress codes, including school policies restricting the use of hair wraps or wearing their natural hair (Dvorak, 2018; Hobdy, 2020; National Women’s Law Center, 2018).

Gendered racial socialization to cope in schools

Black boys and Blacks girls receive gendered racial socialization messages from parents aimed at preparing them to deal with negative stereotypes and microaggressions in schools and facilitate adaptive development. Due to structural racism, which has limited Black families access to economic and social resources, Black families have had to rely on Black women’s financial contribution for economic survival (Anderson & Shapiro, 1996; Boustan & Collins, 2014). Consequently, Black women often assume important social roles within and outside the home, leading them to value endorse androgynous gender roles, reporting high levels of stereotypical female and male characteristics (Buckley & Carter, 2005; Dade & Sloan, 2000). These experiences have shaped how Black women socialize their Black girls, emphasizing qualities such as self‐sufficiency, assertiveness and strength, qualities not similarly valued by white women (Oshin & Milan, 2019). This greater flexibility in gender roles has been linked to higher self‐esteem and more positive body image in Black girls (Buckley & Carter, 2005; Molloy & Herzberger, 2002), but likely bring them into more conflict with pre‐K‐12 teachers, who are overwhelmingly white women. Together, this small body of literature suggests Black girls are being socialized in ways that may bring psychological benefits but heightens their risks in culturally invalidating school contexts. Although there is less research on the school‐specific gendered racial socialization of Black boys, when surveyed, Black boys have demonstrated understandings of their identity that exist outside of rigid gender norms and that consider themselves capable of academic excellence (Andrews, 2009; Buckley, 2018).

Encounters with law enforcement

Another key context for heightened vulnerability for Black boys and Black girls is in their encounters with law enforcement officers who are part of the justice system in their schools and neighborhoods. In recent years, police officers’ use of excessive force and the horrific murders of unarmed Black people by the police have been increasingly documented in the media, leading to widespread protests for police reform. However, media coverage of police brutality have disproportionately focused on Black boys and men, rendering the victimization and murder of Black girls and women invisible because of their dual racial and gender marginalization (i.e., “intersectional invisibility”; Coles & Pasek, 2020; Purdie‐Vaughns & Eibach, 2008). Research suggests that excessive force and sexual violence are the two most common forms of reported police misconduct (Cato Institute, 2010; DeVylder et al., 2017). Further, there is evidence that Black girls are subject to lethal and excessive force from law enforcement at rates that mirror the experiences of Black boys, and are disproportionately affected by police sexual violence (Edwards et al., 2019; Tromadore, 2016). Police excessive force and sexual victimization against Black adolescents are likely rooted in their common dehumanization because of racism (Owusu‐Bempah, 2017), and gender‐specific stereotypes of Black boys being dangerous and criminal and Black girls being sexually lascivious and promiscuous. As such, Black boys and girls share common and unique vulnerabilities in their interactions with law enforcement in the U.S.

Sexual abuse‐to‐prison pipeline

Black girls are also at heightened risk for the sexual abuse‐to‐prison pipeline, which refers to the pathway of gendered violence through which girls are funneled into the juvenile justice system (Anderson & Walerych, 2019; Burson et al., 2019; Saar et al., 2016). Research indicates that a history of sexual abuse or violence is one of the strongest predictors of girls’ involvement in the juvenile justice system, with 31–81% of justice‐involved girls reporting histories of sexual abuse (Miller et al., 2012; Saar et al., 2016). Notably, Black girls’ contact with the juvenile justice system often occurs because of their behavioral and emotional reactions to trauma, such as truancy, running away, curfew violations, and substance use (Baumle, 2018; Saar et al., 2016). Thus, girls are criminalized for their own victimization, and this sexual abuse‐to‐prison pipeline disproportionately affects Black girls who represent the fastest growing population of incarcerated youth (Crenshaw et al., 2015; Quinn et al., 2021). Further, Black girls in the juvenile justice system often fail to receive mental health services to address their trauma symptoms and instead are subject to conditions and practices that can be retraumatizing, such as strip searches and inappropriate use of restraints (Saar et al., 2016). Following their re‐entry back into the community, these girls now face greater barriers to educational attainment and employment and are at increased risk for continued sexual victimization, continuing the vicious cycle of abuse and incarceration. This line of work underscores the importance of adopting an intersectional perspective when attempting to understand the mechanisms by which Black boys and girls are controlled, punished, and placed on a pathway that increases risk for incarceration.

Sex trafficking of minors

Black girls are at increased risk of sexual exploitation through modern‐day sex trafficking. More than half of U.S. human trafficking cases involve the commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC), or the buying, selling, or trading of sexual services from anyone under the age of 18 (Hornor, 2015; Kotrla, 2010). Approximately 200,000 children in the U.S. are victims of CSEC each year (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2014), with the vast majority being underage girls (Polaris, 2019; U.S. Department of Justice, 2011). Black girls constitute a disproportionate number of sexually exploited children in the U.S. (Phillips, 2015). Indeed, a third of sex trafficking victims are Black and 95% of youth identify as female (Office of Juvenile Justice and Deliquency Prevention, 2014). Although sex trafficking affects youth of all demographics, child welfare and juvenile justice involvement, economic hardship (e.g., homelessness), detachment from education, and histories of trauma, increase risk of being trafficked (Polaris, 2019). Compared to girls of other races, Black girls are more likely to experience these risk factors due to centuries of structural racism in the U.S. that have limited Black families’ access to quality housing, education, healthcare, and employment, leaving Black girls especially vulnerable to trafficking and sexual exploitation.

While Black girls are disproportionately affected by child sex trafficking, they are not recognized as victims and are punished and not protected by U.S. law enforcement. Research shows that Black youth represent ~51% of juvenile arrests for commercial sexual acts (FBI, 2019), and this percentage is significantly larger in major metropolitan areas, such as New York City, Los Angeles, Miami, and Dallas. For example, although Black girls only make up 3% of the population in Los Angeles County, they accounted for 92% of youth arrested for prostitution in this region in 2010 (Sabaté, 2012). Notably, antitrafficking efforts are often grounded in the argument that children lack the physical, mental, and emotional maturity to consent to sexual acts. However, racialized, and gendered constructions of Black girls as older, more mature, and more sexually promiscuous then their white counterparts (Epstein et al., 2017), have likely been used to deny Black girls’ access to antitrafficking protections and to justify arresting, prosecuting, and incarcerating them for prostitution (Ocen, 2015). Further, by criminalizing Black girls for their exploitation, the judicial system reinforces stereotypes about Black sexuality and deviancy, which ultimately supports the people and systems that continue to sexually exploit them. In a study conducted by the Urban Institute, sex traffickers admitted during interviews that although trafficking white women and girls would be more profitable, they believed that the penalty for trafficking Black girls would be less severe if they were caught (Dank et al., 2014). Thus, the current legal response to Black girls vulnerabilities to sex trafficking puts them at heightened risk of being targeted by sex traffickers who are keenly aware that the legal system offers little to no protections to Black girls.

Gendered racial socialization to cope with law enforcement encounters and sex abuse

To help youth cope with potential encounters with law enforcement and sexual abuse, parents likely engage in tailored racial socialization messages for their youth. The research on gendered socialization suggests Black boys receive more messages concerning racial barriers (i.e., preparation for bias) compared to Black girls (Peck et al., 2014; Thomas & Speight, 1999). Black girls, in contrast, tend to receive more messages seeking to instill cultural pride (Caughy et al., 2011; Peck et al., 2014). These differences may be rooted in Black parents concerns about how racial discrimination may affect their Black boys compared to their Black girls (Varner & Mandara, 2013). For example, during a series of in‐depth qualitative interviews following the murder of 17‐year‐old Trayvon Martin, parents reported that relative to Black girls, Black boys are confronted with more negative stereotypes; especially, stereotypes that portray them as dangerous (Thomas & Blackmon, 2015). Consequently, parents expressed more concern regarding the physical safety of their sons, which led them to provide specific messages on how to navigate hostile interactions with police and other experiences of racial profiling (Thomas & Blackmon, 2015). Similar messages regarding the physical safety of Back girls were absent. It is possible that Black parents’ heightened concerns for the safety of Black sons relative to their daughters will, in part, be due to gender disparities in media coverage of police violence that shapes Black parents’ concerns for their daughters (Malone Gonzalez, 2022; Samuels et al., 2021).

Moreover, scholars have recently expressed concerns that Black girls are not being prepared to manage experiences of gendered racism, including police sexual violence (Malone Gonzalez, 2019, 2022). Malone Gonzalez (2022) argues that in the same way parents provide Black boys with strategies for avoiding police physical violence, such as keeping their hands in sight, they should also provide Black girls with strategies for mitigating risk of police sexual violence. She notes, “I find strategies for black girls in the predatory talk for police sexual violence can involve explicitly ignoring officers’ commands, including continuing to drive, reaching for a phone, and calling parents during an encounter,” especially when alone or at night (Malone Gonzalez, 2022, p. 36).

INTERVENTION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Highly publicized acts of police brutality and the disproportionate effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on Black families have led to increased concerns regarding the wide‐ranging effects of racial discrimination on the psychological adjustment and outcomes of Black youth. These concerns have been coupled by greater awareness of the unique need and responsibility to reduce risk in Black youth through interventions and policy reform. In considering the importance of history in framing the ACEs of Black boys and girls, it is key to leverage interventions that have been developed for these populations but are often overlooked by researchers and clinicians. For example, Emotional Emancipation Circles were developed by the Community Healing Network in collaboration with the Association of Black Psychologists and have been used to address historical and racial trauma among Black people, including Black youth (Barlow, 2018; Grills et al., 2016). Another advancement in this area has included capitalizing on the buffering effects of racial socialization by directly targeting and strengthening Black parents’ racial socialization competencies. This approach has shown significant promise as an effective strategy for counteracting the pervasive and enduring effects of racial discrimination on Black youth (Anderson et al., 2018; Metzger et al., 2021). However, as efforts to address racial trauma in Black youth continue, it is critical to adopt an intersectional framework that is responsive to the unique experiences and needs of different subgroups of youth. For example, it is possible that racial socialization interventions could be strengthened by attending the intersecting racial and gender identities of Black youth and equipping them the tools for coping with gendered racism.

Research on how racial discrimination varies along gendered lines also has important implications for education reform. Efforts to address racial disparities in discipline and academic outcomes are often based on the experiences of Black boys, implicitly suggesting that the experiences and needs of Black girls are the same as their male counterparts. However, studies reviewed in this article suggest that different factors contribute to the disproportionate use of exclusionary disciplinary practices against Black boys and girls. This research challenges the use of gender‐neutral approaches to educational reform and underscores the need for policies that reflect the racialized and gendered context in which exclusionary punishment is enforced.

Similarly, although police violence against Black girls has received increased public awareness with the launch of the #SayHerName campaign in 2015, efforts to understand the frequency and impact of police violence on Black girls have been challenged by the woefully inadequate amount of data on police violence (Jacobs, 2017). It is often through social media and video‐recorded footage that the public becomes aware of these incidents, and media coverage often focuses on the killings of Black boys and men, while stories of police violence against Black girls and women are buried (Jacobs, 2017; Ritchie, 2017). Further, discussions of police reform often center on excessive use of physical force, but fail to acknowledge sexual violence by police officers, which disproportionately affects Black girls. Thus, to better understand the prevalence of these incidents and identify subgroups of youth at greatest risk of victimization, it is imperative that we continue to demand greater transparency from law enforcement. Specifically, police agencies should be required to document and make publicly available the names of officers accused or convicted of sexual abuse and the details of such incidents, including the age, gender, and race of the victim(s).

While there are important gender differences in Black youths’ experiences of racial discrimination, a recurring theme across studies is the ways in which, Black boys and girls have been dehumanized and robbed the protections of childhood and adolescence that have been afforded to other youth. For youth who are repeatedly told in direct and implicit ways that their lives and pain do not matter, therapeutic approaches that focus on youth psychopathology may be experienced as further invalidating. Thus, when working with Black youth who have experienced racial trauma, it is important for clinicians to remember the numerous ways in which these youth have demonstrated extraordinary resilience and to encourage them to draw on their cultural and family strengths in their healing process.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONCLUSION

While the current review focused on understanding Black youths’ experiences of racism along gendered lines, it is critical to also consider other aspects of their identity, such as sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and country of origin. Relatedly, youth vary in the extent to which they ascribe importance and meaning to being Black and in the extent to which they identify as being masculine or feminine. These individual differences in racial and gender identity may affect how youth interpret and cope with experiences of gendered racism and should be considered in future research.

In sum, Black adolescents’ mental health is framed by several layers of gendered racism that affect their interpersonal experiences, their socialization experiences, and their institutional opportunities. In effect, many of these conceptions of gendered racism serve to erase the youth of Black boys and girls, through historical myths of Black male violence and dangerousness or Black female lasciviousness. Even these conceptions do not capture the full depth and nuance of how Black boys and girls experience ACEs; however, this level of analysis can serve to further reveal how Black boys and girls make sense of their adversities, and thus help to optimize treatments for and research on these populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and Health Disparities under Grant No. P50MD015705. All views and opinions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies or respective institutions. Naila A. Smith held an American Fellowship from AAUW.

[Corrections added on 03rd May 2022, after first online publication: The abstract has been expanded upon for clarity.]

REFERENCES

- Alt, W. E. , Alt, B. S. , & Alt, B. L. (2002). Black soldiers, white wars: Black warriors from antiquity to the present. Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D. , & Shapiro, D. (1996). Racial differences in access to high‐paying jobs and the wage gap between black and white women. ILR Review, 49(2), 273–286. 10.1177/001979399604900206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. E. , & Stevenson, H. C. (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist, 74(1), 63. 10.1037/amp0000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. E. , McKenny, M. , Mitchell, A. , Koku, L. , & Stevenson, H. C. (2018). EMBRacing racial stress and trauma: Preliminary feasibility and coping responses of a racial socialization intervention. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(1), 25–46. 10.1177/0095798417732930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, V. R. , & Walerych, B. M. (2019). Contextualizing the nature of trauma in the juvenile justice trajectories of girls. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 47, 138–153. 10.1080/10852352.2019.1582141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D. J. C. (2009). The construction of Black high‐achiever identities in a predominantly White high school. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 40(3), 297–317. 10.1111/j.1548-1492.2009.01046.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ani, M. D. R. (1981). Let the circle be unbroken: The implications of African spirituality in the diaspora. Nkonimfo. [Google Scholar]

- Assari, S. , Moghani Lankarani, M. , & Caldwell, C. (2017). Discrimination increases suicidal ideation in Black adolescents regardless of ethnicity and gender. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 75. 10.3390/bs7040075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins‐Loria, S. , Macdonald, H. , & Mitterling, C. (2015). Young African American men and the diagnosis of conduct disorder: The neo‐colonization of suffering. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(4), 431–441. 10.1007/s10615-015-0531-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, J. N. (2018). Restoring optimal black mental health and reversing intergenerational trauma in an era of Black Lives Matter. Biography, 41(4), 895–908. 10.1353/bio.2018.0084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumle, D. (2018). Creating the trauma‐to‐prison pipeline: How the US justice system criminalizes structural and interpersonal trauma experienced by girls of color. Family Court Review, 56(4), 695–708. 10.1111/fcre.12384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benner, A. D. , Wang, Y. , Shen, Y. , Boyle, A. E. , Polk, R. , & Cheng, Y.‐P. (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well‐being during adolescence: A meta‐analytic review. American Psychologist, 73(7), 855–883. 10.1037/amp0000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke, D. S. , & Zeichner, A. (2016). Man's heaviest burden: A review of contemporary paradigms and new directions for understanding and preventing masculine aggression. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10, 83–91. 10.1111/spc3.12238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, D. L. , Calhoun, C. D. , Banks, D. E. , Halliday, C. A. , Hughes‐Halbert, C. , & Danielson, C. K. (2021). Making the “C‐ACE” for a culturally‐informed adverse childhood experiences framework to understand the pervasive mental health impact of racism on Black youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(2), 233–247. 10.1007/s40653-020-00319-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Futures Lab (2019). Beyond kings and queens: Gender and politics in the 2019 Black census. https://blackcensus.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. J. , Butler, B. R. , Lewis, C. W. , & Darensbourg, A. (2011). Unmasking the inequitable discipline experiences of urban Black girls: Implications for urban educational stakeholders. The Urban Review, 43(1), 90–106. 10.1007/s11256-009-0148-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boustan, L. P. , & Collins, W. J. (2014). The origins and persistence of Black‐White differences in women’s labor force participation. In Boustan L. P., Frydman C., & Margo R. A. (Eds.), Human capital in history: The American record (pp. 205–240). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart, M. Y. H. (1999). Gender differences in the historical trauma response among the Lakota. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 10(4), 1–21. 10.1300/J045v10n04_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart, M. Y. H. , & DeBruyn, L. M. (1998). The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 8(2), 56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater, P. D. (2005). Ain't I a slave: Slavery reproductive abuse, and reparations. UCLA Women's Law Journal, 14(1), 89–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In Lerner R. M. (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, R. , Staff, J. , Maggs, J. L. , & Dorn, L. D. (2021). Pubertal timing and adolescent alcohol use: The mediating role of parental and peer influences. Child Development, 92(5), e1017–e1037. 10.1111/cdev.13569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, T. R. (2018). Black adolescent males: Intersections among their gender role identity and racial identity and associations with self‐concept (global and school). Child Development, 89(4), e311–e322. 10.1111/cdev.12950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, T. R. , & Carter, R. T. (2005). Black adolescent girls: Do gender role and racial identity: Impact their self‐esteem? Sex Roles, 53(9), 647–661. 10.1007/s11199-005-7731-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burson, E. , Godfrey, E. B. , & Singh, S. (2019). “This is probably the reason why she resorted to that kind of action”: A qualitative analysis of juvenile justice workers attributions for girls’ offending. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 47(2), 154–170. 10.1080/10852352.2019.1582142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race‐based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cato Institute (2010). National Police Misconduct Reporting Project, 2010 Annual Report. Cato Institute. http://www.policemisconduct.net/statistics/2010‐annual‐report [Google Scholar]

- Caughy, M. O. , Nettles, S. M. , & Lima, J. (2011). Profiles of racial socialization among African American parents: Correlates, context, and outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(4), 491–502. 10.1007/s10826-010-9416-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrone, K. M. (1999). The gun‐free schools act of 1994: Zero tolerance takes aim at procedural due process. Pace Law Review, 20, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Christle, C. A. , Jolivette, K. , & Nelson, C. M. (2005). Breaking the school to prison pipeline: Identifying school risk and protective factors for youth delinquency. Exceptionality, 13(2), 69–88. 10.1207/s15327035ex1302_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cimprich, J. (2005). Fort Pillow, a Civil War massacre, and public memory. LSU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, S. M. , & Pasek, J. (2020). Intersectional invisibility revisited: How group prototypes lead to the erasure and exclusion of Black women. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 6(4), 314–324. 10.1037/tps0000256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J. M. , Taylor, M. J. , & Peterson, Z. D. (2017). Reexamining the “Jezebel” Stereotype: The role of implicit and psychosexual attitudes. Western Journal of Black Studies, 41(3/4), 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Gender, black feminism, and black political economy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 568(1), 41–53. 10.1177/000271620056800105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comas‐Díaz, L. , Hall, G. N. , & Neville, H. A. (2019). Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(1), 1–5. 10.1037/amp0000442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. , Ocen, P. , & Nanda, J. (2015). Black girls matter: Pushed out, overpoliced and under protected. African American Policy Forum and Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies. https://www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/09/BlackGirlsMatter_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W. E. (2003). Tracing the historical origins of youth delinquency & violence: Myths & realities about black culture. Journal of Social Issues, 59(1), 67–82. 10.1111/1540-4560.t01-1-00005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, M. , Francois, S. , Rodriguez, G. , & Lee, X. W. (2018). Resilience and coping: An example in African American adolescents. Research in Human Development, 15(3–4), 317–331. 10.1080/15427609.2018.1502547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, A. J. (2014). Tracing the school‐to‐prison pipeline from zero‐tolerance policies to juvenile justice dispositions. The Georgetown Law Journal, 102, 1251–1277. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, D. F. (2020). Reading the dead: A Black feminist poethical reading of global capital. In King T. L., Navarro J., & Smith A. (Eds.), Otherwise worlds: Against settler colonialism and anti‐Blackness (pp. 77–93). Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dade, L. R. , & Sloan, L. R. (2000). An investigation of sex‐role stereotypes in African Americans. Journal of Black Studies, 30(5), 676–690. 10.1177/002193470003000503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dank, M. , Khan, B. , Downey, P. M. , Kotonias, C. , Mayer, D. , Owens, C. , Pacifici, L. , & Yu, L. (2014). Estimating the size and structure of the underground commercial sex economy in eight major US cities. Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Degruy‐Leary, J. (1994). Post‐traumatic slave syndrome: America's legacy of enduring injury. Caban Productions. [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder, J. E. , Oh, H. Y. , Nam, B. , Sharpe, T. L. , Lehmann, M. , & Link, B. G. (2017). Prevalence, demographic variation and psychological correlates of exposure to police victimization in four US cities. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26(5), 466–477. 10.1017/S2045796016000810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, P. Are Black girls unfairly targeted for dress‐code violations at school? You bet they are. The Washington Post. April 26, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/are‐black‐girls‐unfairly‐targeted‐for‐dress‐code‐violations‐at‐school‐you‐bet‐they‐are/2018/04/26/623a91dc‐4958‐11e8‐9072‐f6d4bc32f223_story.html [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, F. , Lee, H. , & Esposito, M. (2019). Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(34), 16793–16798. 10.1073/pnas.1821204116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English, D. , Lambert, S. F. , Tynes, B. M. , Bowleg, L. , Zea, M. C. , & Howard, L. C. (2020). Daily multidimensional racial discrimination among Black U.S. American adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 66, 101068. 10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, R. , Blake, J. , & González, T. (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of Black girls’ childhood. Center on Poverty and Inequality. http://www.law.georgetown.edu/academics/centers‐institutes/povertyinequality/upload/girlhood‐interrupted.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Essed, P. (1991). Understanding everyday racism: An interdisciplinary theory (pp. x, 322). Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigations (2019). 2019 FBI crime in the United States: Arrests by race and ethnicity [Data file]. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime‐in‐the‐u.s/2019/crime‐in‐the‐u.s.‐2019/topic‐pages/tables/table‐43 [Google Scholar]

- Galán, C. A. , Stokes, L. R. , Szoko, N. , Abebe, K. Z. , & Culyba, A. J. (2021). Exploration of experiences and perpetration of identity‐based bullying among adolescents by race/ethnicity and other marginalized identities. JAMA Network Open, 4(7), e2116364–e2116364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami, N. , & Peplau, L. A. (2013). An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes: Testing three hypotheses. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), 113–127. 10.1177/0361684312464203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, P. , Haight, W. , Cho, M. , Nashandi, N. J. C. , & Yoon, Y. J. (2019). A mixed methods study of Black Girls’ vulnerability to out‐of‐school suspensions: The intersection of race and gender. Children and Youth Services Review, 102, 169–176. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Girvan, E. J. , Gion, C. , McIntosh, K. , & Smolkowski, K. (2017). The relative contribution of subjective office referrals to racial disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(3), 392–404. 10.1037/spq0000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff, P. A. , Jackson, M. C. , Di Leone, B. A. L. , Culotta, C. M. , & DiTomasso, N. A. (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526. 10.1037/a0035663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone, J. P. (2013). Redressing First Nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(5), 683–706. 10.1177/1363461513487669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M. L. , Way, N. , & Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 218. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills, C. N. , Aird, E. G. , & Rowe, D. (2016). Breathe, baby, breathe: Clearing the way for the emotional emancipation of Black people. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 16(3), 333–343. 10.1177/1532708616634839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom, J. A. , Nicholson‐Crotty, J. , & NicholsonCrotty, S. (2009). Race, region, and representative bureaucracy. Public Administration Review, 69, 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Gump, J. (2010). Reality matters: The shadow of trauma on African American subjectivity. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27(1), 42–54. 10.1037/a0018639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, S. (2019). Wayward lives, beautiful experiments: Intimate histories of social upheaval. W.W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Heard‐Garris, N. J. , Cale, M. , Camaj, L. , Hamati, M. C. , & Dominguez, T. P. (2018). Transmitting trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 230–240. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, J. I. , & Schmahl, C. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 420. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobdy, D. Florida School Threatens to Expel African‐American Girl for Wearing ‘Natural Hair’. Essence. October 27, 2020. https://www.essence.com/news/florida‐school‐threatens‐expel‐african‐american‐girl‐wearing‐natural‐hair/ [Google Scholar]

- Hornor, G. (2015). Domestic minor sex trafficking: What the PNP needs to know. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 29(1), 88–94. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. , Del Toro, J. , Harding, J. F. , Way, N. , & Rarick, J. R. D. (2016). Trajectories of discrimination across adolescence: Associations with academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. Child Development, 87(5), 1337–1351. 10.1111/cdev.12591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. , Rodriguez, J. , Smith, E. P. , Johnson, D. J. , Stevenson, H. C. , & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic‐racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. L. , Watford, J. A. , & Del Toro, J. (2016). A transactional/ecological perspective on ethnic–racial identity, socialization, and discrimination. In Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 51, pp. 1–41). Elsevier. 10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby, E. M. , & Shaw, D. S. (2002). Neighborhood contextual factors and early‐starting antisocial pathways. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(1), 21–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, M. S. (2017). The violent state: Black women's invisible struggle against police violence. William and Mary Journal of Women and the Law, 24(1), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol24/iss1/4 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. M. (2020). Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World. [Google Scholar]

- Khalek, R. (2011). 20 years in prison for sending your kids to the wrong school? Inequality in school systems leads parents to big risks. AlterNet. [Google Scholar]

- Kotrla, K. (2010). Domestic minor sex trafficking in the United States. Social Work, 55(2), 181–187. 10.1093/sw/55.2.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Library of Congress . (n.d.). The murder of Emmett Till. https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil‐rights‐history‐project/articles‐and‐essays/murder‐of‐emmett‐till/

- Lindsay, C. A. , & Hart, C. M. (2017). Exposure to same‐race teachers and student disciplinary outcomes for Black students in North Carolina. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(3), 485–510. 10.3102/0162373717693109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loyd, A. B. , Hotton, A. L. , Walden, A. L. , Kendall, A. D. , Emerson, E. , & Donenberg, G. R. (2019). Associations of ethnic/racial discrimination with internalizing symptoms and externalizing behaviors among juvenile justice‐involved youth of color. Journal of Adolescence, 75, 138–150. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone Gonzalez, S. (2019). Making it home: An intersectional analysis of the police talk. Gender & Society, 33(3), 363–386. 10.1177/0891243219828340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malone Gonzalez, S. (2022). Black girls and the talk? Policing, parenting, and the politics of protection. Social Problems, 69(1), 22–38. 10.1093/socpro/spaa032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, K. J. , & Stewart, J. Jr (1992). The impact of representative bureaucracies: Educational systems and public policies. The American Review of Public Administration, 22(3), 157–171. 10.1177/027507409202200301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, I. W. , Anderson, R. E. , Are, F. , & Ritchwood, T. (2021). Healing interpersonal and racial trauma: Integrating racial socialization into trauma‐focused cognitive behavioral therapy for African American youth. Child Maltreatment, 26(1), 17–27. 10.1177/1077559520921457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. , Leve, L. D. , Kerig, P. K. , (Eds.), (2012). Delinquent girls: Contexts, relationships, and adaptation. Springer Books. 10.1007/978-1-4614-0415-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moriearty, P. L. , & Carson, W. (2012). Cognitive warfare and young Black males in America. Journal of Gender, Race & Justice, 15, 281–313. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E. W. (2007). “Ladies” or “Loudies”? Perceptions and experiences of Black girls in classrooms. Youth and Society, 38, 490–515. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M. W. (2016). Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in schools. The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Campaign to Reform State Juvenile Justice Systems (2013). The Fourth Wave: Juvenile Justice Reforms for the Twenty‐first Century. http://www.modelsforchange.net/publications/530th Wave Paper.

- National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America . (2021). The harm is to our genes: Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance & systemic racism in the United States. N’COBRA Report 2021. https://www.ncobraonline.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/06/NCOBRA‐2021‐The‐Harm‐Is‐To‐Our‐Genes‐Full‐Report‐11.15‐compressed.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Women’s Law Center . (2018). Dress coded: Black girls, bodies and bias in D.C. schools. https://nwlc.org/resource/dresscoded‐ii/

- Nobles, W. W. (1978). Toward an empirical and theoretical framework for defining black families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 40(4), 679–688. 10.2307/351188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ocen, P. A. (2015). (E)racing childhood: Examining the racialized construction of childhood and innocence in the treatment of sexually exploited minors. UCLA Law Review, 62(6), 1586–1641. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2014). Commercial sexual exploitation of children/sex trafficking. https://www.ojjdp.gov/mpg/litreviews/CSECSexTrafficking.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Oshin, L. A. , & Milan, S. (2019). My strong, Black daughter: Racial/ethnic differences in the attributes mothers value for their daughters. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 179–187. 10.1037/cdp0000206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu‐Bempah, A. (2017). Race and policing in historical context: Dehumanization and the policing of Black people in the 21st century. Theoretical Criminology, 21(1), 23–34. 10.1177/1362480616677493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter, L. M. , & Coll, C. G. (2009). Racism and child health: A review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(3), 255–263. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed5a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck, S. C. , Brodish, A. B. , Malanchuk, O. , Banerjee, M. , & Eccles, J. S. (2014). Racial/ethnic socialization and identity development in Black families: The role of parent and youth reports. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1897–1909. 10.1037/a0036800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J. (2015). Black girls and the (im)possibilities of victim trope: The intersectional failures of legal and advocacy interventions in the commercial sexual exploitation of minors in the United States. UCLA Law Review, 62(6), 1642–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, D. (2002). The jezebel stereotype. http://fir.ferris.edu:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2323/4778/Jezebel%20Stereotype.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Polaris Project (2019). 2019 Data Report. https://polarisproject.org/wp‐content/uploads/2019/09/Polaris‐2019‐US‐National‐Human‐Trafficking‐Hotline‐Data‐Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Purdie‐Vaughns, V. , & Eibach, R. P. (2008). Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate‐group identities. Sex Roles, 59, 377–391. 10.1007/s11199-008-9424-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, C. R. , Boyd, D. T. , Kim, B.‐K. , Menon, S. E. , Logan‐Greene, P. , Asemota, E. , Diclemente, R. J. , & Voisin, D. (2021). The influence of familial and peer social support on post‐traumatic stress disorder among Black girls in juvenile correctional facilities. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(7), 867–883. 10.1177/0093854820972731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, A. J. (2017). Invisible no more: Police violence against black women and women of color. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saar, M. S. , Epstein, R. , Rosenthal, L. , & Vafa, Y. (2016). The sexual abuse to prison pipeline: The girls’ story. Center on Poverty and Inequality, Georgetown Law. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté, A. (2012). Los Angeles task force takes on underage prostitution. https://abcnews.go.com/ABC_Univision/News/los‐angeles‐task‐force‐takes‐underageprostitution/story?id=17844111

- Saleem, F. T. , Anderson, R. E. , & Williams, M. (2020). Addressing the “myth” of racial trauma: Developmental and ecological considerations for youth of color. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–14. 10.1007/s10567-019-00304-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, A. , Mehta, D. , & Wiederkehr, A. (2021). Why Black Women are often missing from conversations about police violence. Five Thirty‐Eight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why‐black‐women‐are‐often‐missing‐from‐conversations‐about‐police‐violence/ [Google Scholar]

- Spillers, H. J. (1987). Mama's baby, papa's maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics, 17(2), 65–81. 10.2307/464747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue, D. W. , Nadal, K. L. , Capodilupo, C. M. , Lin, A. I. , Torino, G. C. , & Rivera, D. P. (2008). Racial microaggressions against Black Americans: Implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 330–338. 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00517.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik, J. , & Coatsworth, J. D. (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In Glantz M. D., & Hartel C. R. (Eds.), Drug abuse: Origins & interventions (pp. 331–366). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10341-014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. J. , & Blackmon, S. M. (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41(1), 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. J. , & Speight, S. L. (1999). Racial identity and racial socialization attitudes of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 25(2), 152–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tromadore, C. E. (2016). Police officer sexual misconduct: An urgent call to action in a context disproportionately threatening women of color. Harvard Journal on Racial & Ethnic Justice, 32, 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. , & Hill, N. E. (2020). Ethnic–racial socialization in the family: A decade’s advance on precursors and outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 244–271. 10.1111/jomf.12622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Education (2018). Exclusionary discipline practices in schools 2017–2018. Retrieved from https://ocrdata.ed.gov/assets/downloads/crdc‐exclusionary‐school‐discipline.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Justice (2011). Characteristics of suspected human trafficking incidents, 2008–2010. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cshti0810.pdf

- Varner, F. , & Mandara, J. (2013). Discrimination concerns and expectations as explanations for gendered socialization in African American families. Child Development, 84(3), 875–890. 10.1111/cdev.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.‐T. , Henry, D. A. , Smith, L. V. , Huguley, J. P. , & Guo, J. (2020). Parental ethnic‐racial socialization practices and children of color’s psychosocial and behavioral adjustment: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. American Psychologist, 75(1), 1–22. 10.1037/amp0000464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch, K. (2007). Black criminal stereotypes and racial profiling. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(3), 276–288. 10.1177/1043986207306870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilderson, F. B. (2009). Grammar & ghosts: The performative limits of African freedom. Theatre Survey, 50(1), 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson, I. (2011). The warmth of other suns: The epic story of America's great migration. Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. G. , & Lewis, J. A. (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions and depressive symptoms among Black women: A moderated mediation model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(3), 368–380. 10.1177/0361684319832511fw [DOI] [Google Scholar]