Abstract

The genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato was assessed in individual adult Ixodes ricinus ticks from Europe by direct PCR amplification of spirochetal DNA followed by genospecies-specific hybridization. Analysis of mixed infections in the ticks showed that B. garinii and B. valaisiana segregate from B. afzelii. This and previous findings suggest that host complement interacts with spirochetes in the tick, thereby playing an important role in the ecology of Lyme borreliosis.

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato is a bacterial species complex comprising 10 named genospecies and several genomic groups. All known species and genotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu lato are tick transmitted and are maintained in nature by complex zoonotic transmission cycles, involving more than 50 avian and mammalian wildlife species as reservoir hosts for the spirochetes in Europe (3, 14).

Six genospecies, B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. valaisiana, B. lusitaniae, B. bissettii, and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, are known to be prevalent in Europe (2, 4, 7, 28, 29). All these genospecies may cocirculate in local tick populations, suggesting that the local diversity of B. burgdorferi sensu lato can be as high as the regional or continental diversity (5, 7, 24, 26, 27, 29). Individual ticks may be infected with multiple genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato; however, mixed infections seem to be much rarer than single infections (4, 7, 8, 11, 13, 16, 26, 27). Although information on the pattern of mixed infections in individual ticks may reveal important principles of the biology and ecology of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, only a few studies provide information on this aspect (4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 16, 26).

Adult questing Ixodes ricinus ticks were collected in sylvatic habitats by blanket dragging (14) in the springs of 1996 and 1999. The habitats were located around Riga (Latvia), Bratislava (Slovakia), Bonn (Germany), and Lisbon (Portugal, two distinct sites) and in the New Forest (United Kingdom). B. burgdorferi sensu lato infection status was determined by PCR and the reverse line blot assay as described previously (2, 16, 23, 26).

The null hypothesis that the different genotypes were distributed independently of each other in individual ticks was statistically tested. The frequency data from each country were considered separately. The probability of a tick containing any one genotype was calculated from the data as follows: Σ(all ticks containing that genotype, whether as mixed or single infection)/Σ(all ticks tested). The probabilities of mixed and single infections were calculated assuming independent distributions in order to generate a set of expected frequencies.

A total of 1,483 questing adult ticks were analyzed, and 461 (31.0%) were found to be infected with B. burgdorferi sensu lato (Table 1). The most prevalent genospecies was B. afzelii (39.3%), followed by B. garinii (21.2%), B. valaisiana (12.8%), B. lusitaniae (5.8%), and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (1.5%). The three genospecies B. afzelii, B. garinii, and B. valaisiana were present in all local tick populations collected in Slovakia (Bratislava), Latvia (Riga), Germany (Bonn), and Portugal (the Mafra site). These three genospecies accounted for 94.2% of all infections (Table 1; Fig. 1). Of the 410 typeable infections, 372 (90.7%) were single infections. Of the ticks infected with B. garinii, 24% were infected simultaneously with B. valaisiana, and 34% of the ticks harboring B. valaisiana were concurrently infected with B. garinii (Fig. 1). In contrast, only 1% of the B. afzelii infections occurred together with B. garinii, and no mixed infection of B. afzelii and B. valaisiana was observed. B. afzelii was absent from the United Kingdom site (16) and the Grândola site in Portugal (2). Therefore, these two sites were omitted in the statistical analysis. Of the remaining four sets of frequency data presented in the table, three have sufficient data to statistically test the hypothesis that the different genotypes are distributed independently of each other in individual ticks, namely, the data from Slovakia, Latvia, and Germany. Fewer mixed infections of B. garinii-B. afzelii composition were detected in individual ticks than expected in each of the three cases, and in two out of three this difference was significant. Significantly more mixed infections of B. garinii-B. valaisiana composition than expected under neutralist assumptions were observed in the data set from Slovakia (Slovakia, χ22 = 96.1, P = 1.05 × 10−20; Latvia, χ12 = 6.41, P = 0.0113; and Germany, χ12 = 1.38, P = 0.240).

TABLE 1.

Infection of questing adult I. ricinus with B. burgdorferi sensu latoa

| Country or site | No. of ticks tested | No. (%) of ticks infected by different genospecies

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBU sensu lato | BBU | BGA | BVA | BAF | BLU | BGA/BVA | BGA/BAF | BBU/BAF | UT | ||

| Slovakia | 585 | 237 (40.5) | 3 (1.3) | 37 (15.6) | 22 (9.3) | 125 (52.7) | 0 (0) | 20 (8.4) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 26 (10.9) |

| Latvia | 300 | 94 (31.3) | 3 (3.1) | 32 (34.0) | 17 (18.0) | 37 (39.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Germany | 226 | 41 (18.1) | 0 (0) | 14 (34.0) | 5 (12.2) | 18 (43.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.3) |

| PM | 217 | 32 (14.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (25.0) | 12 (37.5) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (18.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (15.6) |

| Subtotal | 1,328 | 404 (30.4) | 6 (1.5) | 91 (22.5) | 56 (13.8) | 181 (44.8) | 0 (0) | 29 (7.2) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.0) | 35 (8.7) |

| PGb | 55 | 41 (74.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (65.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (34.1) |

| United Kingdomc | 100 | 16 (16.0) | 1 (6.2) | 7 (43.7) | 3 (18.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (18.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Total | 1,483 | 461 (31.0) | 7 (1.5) | 98 (21.2) | 59 (12.8) | 181 (39.3) | 27 (5.8) | 32 (6.9) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.9) | 51 (11.1) |

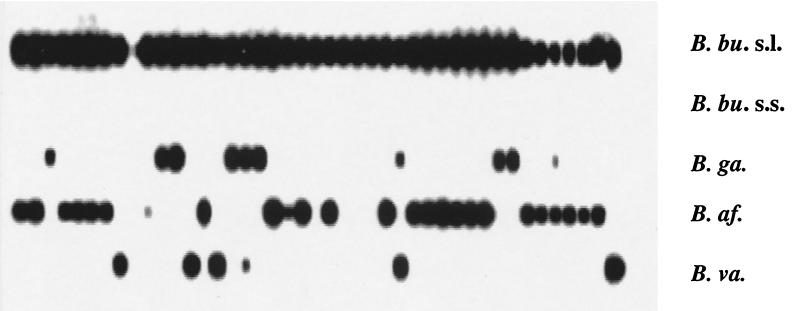

FIG. 1.

Reverse line blot assay on PCR products of the 5S-23S intergenic spacer of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (B. bu. s.l.) derived from questing adult I. ricinus ticks from Slovakia. Representative samples are shown. Briefly, PCR products of B. burgdorferi sensu lato were hybridized to membrane-bound DNA probes specific for B. burgdorferi sensu lato, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.), B. garinii (B. ga.), B. afzelii (B. af.), and B. valaisiana (B. va.). No DNA probe was available for B. bissettii. The PCR products per tick sample are ordered from the left to the right.

The present study yielded two major findings: (i) the majority of infected ticks harbored one genospecies only, and (ii) B. garinii and B. valaisiana constituted the majority of multiple infections, whereas the combination of B. garinii and B. afzelii occurred significantly less frequently than expected.

It has previously been shown that the PCR targeting the 5S-23S intergenic spacer of B. burgdorferi sensu lato does not preferentially amplify Borrelia genotypes (2, 16, 26). In addition, genotyping of PCR products by the reverse line blot assay readily detects mixed infections at different ratios of DNA (16, 26), indicating that the present findings are likely to reflect the true genospecies diversity of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in the ticks analyzed. No DNA probe specific for B. bissettii was available. It is, therefore, possible that some of the untypeable samples fall into this genospecies.

It is now accepted that B. afzelii, B. garinii, and B. valaisiana are the most abundant genospecies in central Europe, often prevailing sympatrically in local I. ricinus populations (4, 7, 11, 16, 26, 27–29). The data from the present study are in line with these previous studies. As questing adult I. ricinus ticks have a history of two blood meals on diverse hosts (25), Borrelia infections may accumulate with the number of infectious blood meals (10, 12, 16). Cumulative acquisition of spirochetes upon consecutive infectious blood meals or superinfection of ticks already infected transovarially could explain the presence of dual infections in individual ticks. In addition, cotransmission of multiple strains from an individual host that contains a mixed infection may result in polyclonal infection of a single tick. Assuming equal transmission coefficients for the Borrelia genospecies throughout the transmission cycle (25), the frequency distribution of genotypes in individual ticks should match the frequency distribution at the population level. The pattern that emerges from the present study, however, indicates that this is not the case; B. garinii and B. valaisiana on the one hand and B. azfelii on the other hand seem to colonize individual ticks in a mutually exclusive way. This pattern cannot be attributed to geographic separation, since these three genospecies were found to circulate sympatrically in all of the central European sites analyzed. For this reason, it is likely that physiological or immunological factors shape the diversity of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in individual ticks.

In this paper an underlying mechanism is proposed for this observed pattern. It has recently been reported that the genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato differ in their resistance to the alternative pathway of the hosts' complement system, depending on the genetic background of the spirochete and the source of serum (15). Rodent complement readily lyses particular genotypes of cultured B. garinii (type strains 20047, prevalent in western Europe) and B. valaisiana but not B. afzelii, whereas avian complement lyses the spirochetes in the reverse pattern. Interestingly, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto displays partial resistance to both avian and mammalian complement (15). The pattern of complement-mediated lysis matches the pattern of transmission competence of the major rodent and avian hosts for B. burgdorferi sensu lato (8–10, 16, 21), suggesting that resistance and/or sensitivity to complement is a key factor in Lyme disease ecology (15). The fact that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto exhibits only partial resistance to complement from mammalian and avian hosts from Europe may in part explain its low prevalence in the Old World.

Host complement has been demonstrated to be active in the midgut of feeding I. ricinus ticks (22). It is likely, therefore, that host complement selectively acts on spirochetes in the midgut of the tick with an effect similar to that observed in vitro, thereby effectively reducing the probability of avian- and rodent-associated Borrelia to coinfect individual ticks.

Although apparently rare, mixed infections of B. garinii and B. afzelii do occasionally occur in individual ticks (7, 8, 11, 13). This may be related to the presence of complement-deficient vertebrate hosts (1) or to the circulation of particular genotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. In fact, diverse genotypes of B. garinii from localities in eastern Europe and Asia as well as OspA serotype 4 strains have been linked with rodent-tick transmission cycles (6, 18–20). In addition, it is possible that spirochetes evade complement-mediated selection in systemically infected ticks (17).

Altogether, the data corroborate earlier observations that the genotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu lato are not only differentially acquired from a host but are also differentially transmitted to the next developmental stage of the tick. In quantitative terms, host-to-tick and tick-to-tick transmission coefficients (25) seem to vary significantly with the genotype of Borrelia and source of blood meal. The findings of this study support the conclusion that B. burgdorferi sensu lato is maintained in nature through distinct transmission cycles, mainly involving small mammalian and avian hosts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Spratt, Patricia A. Nuttall, and Mike Harris for support.

This study was funded by the British Council, The Wellcome Trust (grants 050854/Z/97/Z and 054292/Z/98/Z), the Natural Environment Research Council (grant GT 04/98/TS/2290) (United Kingdom), and the German Academic Exchange Service (to S.E.) (Germany).

REFERENCES

- 1.Colten H R, Rosen F S. Complement deficiencies. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:809–834. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.004113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Michelis S, Sewell H-S, Collares-Pereira M, Santos-Reis M, Schouls L M, Benes V, Holmes E C, Kurtenbach K. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks from mainland Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2128–2133. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2128-2133.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gern L, Estrada-Pena A, Frandsen F, Gray J S, Jaenson T G T, Jongejan F, Kahl O, Korenberg E, Mehl R, Nuttall P A. European reservoir hosts of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1998;287:196–204. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gern L, Hu C M, Kocianova E, Vyrostekova V, Rehacek J. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates obtained from Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in Slovakia. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:665–669. doi: 10.1023/a:1007660430664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttman D S, Wang P W, Wang I N, Bosler E M, Luft B J, Dykhuizen D E. Multiple infections of Ixodes scapularis ticks by Borrelia burgdorferi as revealed by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:652–656. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.652-656.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu C M, Wilske B, Fingerle V, Lobet Y, Gern L. Transmission of Borrelia garinii OspA serotype 4 to BALB/c mice by Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in the field. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1169–1171. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.1169-1171.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubalek Z, Halouzka J. Distribution of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genomic groups in Europe, a review. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:951–957. doi: 10.1023/a:1007426304900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humair P F, Peter O, Wallich R, Gern L. Strain variation of Lyme disease spirochetes isolated from Ixodes ricinus ticks and rodents collected in two endemic areas in Switzerland. J Med Entomol. 1995;32:433–438. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humair P F, Postic D, Wallich R, Gern L. An avian reservoir (Turdus merula) of the Lyme borreliosis spirochetes. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1998;287:521–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humair P F, Rais O, Gern L. Transmission of Borrelia afzelii from Apodemus mice and Clethrionomys voles to Ixodes ricinus ticks: differential transmission pattern and overwintering maintenance. Parasitology. 1999;118:33–42. doi: 10.1017/s0031182098003564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junttila T, Peltomaa M, Soini H, Marjamäki M, Viljanen M K. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus ticks in urban recreational areas of Helsinki. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1361–1365. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1361-1365.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahl O, Janetzki C, Gray J S, Stein J, Bauch R J. Tick infection rates with Borrelia: Ixodes ricinus versus Haemaphysalis concinna and Dermacentor reticulatus in two locations in eastern Germany. Med Vet Entomol. 1992;6:363–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1992.tb00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirstein F, Rijpkema S, Molkenboer M, Gray J S. The distribution and prevalence of B. burgdorferi genomospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Ireland. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:67–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1007360422975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtenbach K, Kampen H, Dizij A, Arndt S, Seitz H M, Schaible U E, Simon M M. Infestation of rodents with larval Ixodes ricinus L. (Acari: Ixodidae) is an important factor in the transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in German woodlands. J Med Entomol. 1995;32:807–817. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtenbach K, Sewell H-S, Ogden N H, Randolph S E, Nuttall P A. Serum complement sensitivity as a key factor in Lyme disease ecology. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1248–1251. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1248-1251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtenbach K, Peacey M, Rijpkema S G T, Hoodless A N, Nuttall P A, Randolph S E. Differential transmission of the genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by game birds and small rodents in England. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1169–1174. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1169-1174.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebet N, Gern L. Histological examination of Borrelia burgdorferi infections in unfed Ixodes ricinus nymphs. Exp Appl Acarol. 1994;18:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuzawa T, Iwaki A, Sato Y, Miyamoto K, Korenberg E I, Yanagihara Y. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolated in near eastern Russia. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakao M, Miyamoto K, Fukunaga M. Lyme disease spirochetes in Japan: enzootic transmission cycles in birds, rodents, and Ixodes persulcatus ticks. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:878–882. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakao M, Miyamoto K, Fukunaga M. Borrelia japonica in nature: genotypic identification of spirochetes isolated from Japanese small mammals. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:805–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsen B, Jaenson T G T, Bergström S A. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato-infected ticks on migrating birds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3082–3087. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3082-3087.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papatheodorou V, Brossard M. C-3 levels in the sera of rabbits infested and reinfested with Ixodes ricinus L. and in midguts of fed ticks. Exp Appl Acarol. 1987;3:53–59. doi: 10.1007/BF01200413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A D, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qui W-G, Bosler E, Campbell J R, Ugine G D, Wang I-N, Luft B J, Dykhuizen D E. A population genetic study of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto from eastern Long Island, New York, suggested frequency-dependent selection, gene flow and host adaptation. Hereditas. 1997;127:203–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1997.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randolph S E, Craine N G A. A general framework for comparative quantitative studies on the transmission of tick-borne diseases using Lyme borreliosis in Europe as an example. J Med Entomol. 1995;32:765–777. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.6.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rijpkema S G T, Molkenboer M J C H, Schouls L M, Jongejan F, Schellekens J F P. Simultaneous detection and genotyping of three genomic groups of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Dutch Ixodes ricinus ticks by characterization of the amplified intergenic spacer region between 5S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3091–3095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3091-3095.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schouls L M, van de Pol I, Rijpkema S G T, Schot C S. Detection and identification of Ehrlichia, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and Bartonella species in Dutch Ixodes ricinus ticks. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2215–2222. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2215-2222.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis and emerging tick-borne diseases in Europe. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:847–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strle F. Lyme borreliosis in Slovenia. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1999;289:643–652. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(99)80023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]