Abstract

Bacterial strains were isolated from beach water samples using the original Environmental Protection Agency method for Escherichia coli enumeration and analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Identical PFGE patterns were found for numerous isolates from 4 of the 9 days sampled, suggesting environmental replication. 16S rRNA gene sequencing, API 20E biochemical testing, and the absence of β-glucuronidase activity revealed that these clonal isolates were Klebsiella, Citrobacter, and Enterobacter spp. In contrast, 82% of the nonclonal isolates from water samples were confirmed to be E. coli, and 16% were identified as other fecal coliforms. These nonclonal isolates produced a diverse range of PFGE patterns similar to those of isolates obtained directly from untreated sewage and gull droppings. β-Glucuronidase activity was critical in distinguishing E. coli from other fecal coliforms, particularly for the clonal isolates. These findings demonstrate that E. coli is a better indicator of fecal pollution than fecal coliforms, which may replicate in the environment and falsely elevate indicator organism levels.

Contamination of recreational water by farm waste runoff, sewage overflows, and other sources of fecal pollution that may contain pathogenic bacteria and viruses creates a serious water quality problem in the United States. Freshwaters are routinely monitored for fecal pollution using Escherichia coli as an indicator organism. This procedure—recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—is based on epidemiological studies that demonstrate a direct relationship between the density of E. coli organisms in water and the occurrence of swimming-associated gastroenteritis (6, 21, 29).

Although E. coli is the EPA-recommended indicator of fecal pollution, fecal coliforms (FC) continue to be widely used for monitoring of recreational waters, according to data reported by the EPA Beaches Environmental Assessment, Closure, and Health Program (http://www.epa.gov/ost/beaches/). E. coli is considered a more specific indicator of fecal pollution than FC, as FC have been found in ambient waters in the absence of apparent fecal pollution and may establish viable populations when high levels of carbohydrates are available as a nutrient source (28). Byamukama et al. attributed the discriminatory power of E. coli as an indicator organism to its weak ability to replicate in the natural environment (4). However, recent findings suggest that E. coli may occur in ambient waters in the absence of apparent fecal pollution, pointing to prolonged survival or replication of E. coli in subtropical or tropical environments (5, 13, 16, 23, 24). Solo-Gabriele et al. (25) reported E. coli multiplication in riverbank soil during drying and wetting cycles in laboratory experiments that simulate tidal activity. Conflicting conclusions regarding the ability of E. coli to replicate outside its host may arise from factors specific to each data set, such as climate and differing isolation methods for E. coli and FC among studies (4). If it occurs, however, bacterial replication in such systems would lead to elevated E. coli counts beyond what actually is introduced from fecal contamination events (25). A complication in assessing the environmental viability of E. coli is the difficulty in differentiating replication from simple accumulation of cells in waters subject to regular contamination.

The aim of this work was to determine if E. coli replication in the environment contributed to high levels of this indicator organism at a beach site that historically has had poor water quality. The main area of study, South Shore Beach in Milwaukee, Wis., is subject to contamination by combined sewer overflows (CSOs) and urban and agricultural runoff from the Milwaukee River Basin that empties into the Milwaukee Harbor via three major tributaries. A large population of ring-billed gulls at the site, at times reaching up to 300 individuals, may also adversely affect water quality (18). In addition, the beach area is enclosed on three sides by a break wall that reduces mixing and dilution effects. The City of Milwaukee Health Department reported E. coli levels in excess of EPA limits for recreational water (<235 E. coli 100 ml−1) on 32 days in 1999 and 42 days in 2000 during the swimming season (data provided by the City of Milwaukee Health Department). In 1999, elevated E. coli levels did not always coincide with known factors such as rainfall or CSOs, and several out-of-limit days actually occurred during hot, dry weather. In 2000, there were high E. coli counts following rainfall and CSO events, but E. coli counts were detected at equally high levels when rainfall occurred with no CSO event.

Water samples were collected on five consecutive days during each of the months June, July, and August in 2000 (Table 1). Samples were also taken 24 h after two CSO events (3 July and 13 September 2000). Samples were obtained 2 m from shore at a depth of 45 cm using 20 sterile 50-ml polypropylene centrifuge tubes for each sample to ensure that replication within the container would not affect results. Samples were placed in the dark on ice and processed within 6 h of collection in adherence to EPA standard methods (30). Water temperature and turbidity data were obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey; data were collected using sondes in place at the site. Rainfall data was obtained from the U.S. Meteorological Service.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial parameters, meteorological and marine conditions, and occurrence of clonal bacterial populations in water samples

| Sample date in 2000 (mo/day) | Total no. of E. coli organisms (CFU 100 ml−1)a | Water temp (°F) | Turbidity (nephelometric units) | Rainfall in previous 24 h (in.) | No. of days since last CSO | No. and type of PFGE patterns (no. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6/25 | 125 | 63 | NTd | 0.2 | 22 | NT |

| 6/26 | 375 | 63 | 1.8 | 0 | 23 | 15 unique |

| 6/27 | 721 | 65 | 0.5 | 0 | 24 | 15 unique |

| 6/28 | 50 | 61 | 1.6 | 0.38 | 25 | NT |

| 6/29 | 301 | 66 | 1.8 | 0 | 26 | NT |

| 7/3 | 2,785 | 60 | 17.3 | 0.23b | 1 | 9 unique |

| A (8) | ||||||

| B (3) | ||||||

| 7/17 | 284 | 76 | 2.5 | 0 | 15 | 16 unique |

| C (4) | ||||||

| 7/18 | 210 | 72 | 2.1 | 0 | 16 | 7 unique |

| C (13) | ||||||

| 7/19 | 263 | 71 | 3.7 | 0 | 17 | NT |

| 7/20 | 350 | 70 | 2.8 | 0.03 | 18 | 20 unique |

| 7/21 | 594 | 72 | 2.8 | 0 | 19 | NT |

| 8/15 | 935 | 81 | 1.6 | 0 | 9 | 14 unique |

| D (6) | ||||||

| 8/16 | 349 | 74 | 1.7 | 1.19 | 10 | 20 unique |

| 8/17 | 2,139 | 69 | 30.7 | 0.21 | 11 | NT |

| 8/18 | 451 | 71 | 3 | 0.0 | 12 | NT |

| 8/19 | 231 | 75 | NT | 0.0 | 13 | NT |

| 9/13 | 1,846 | 70 | 6.7 | 2.51c | 1 | 20 unique |

The number of E. coli organisms was determined using the original EPA method.

The amount of rainfall in the previous 48 h was 4.65 in.

The amount of rainfall in the previous 48 h was 2.8 in.

NT, not tested.

Water samples were analyzed according to the EPA original method for E. coli enumeration (30), which is the same methodology used by the City of Milwaukee Health Department. Sample volumes of 100 ml were vacuum filtered in duplicate through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) and placed on m-TEC agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) using sterile forceps. Sample volumes of 1 and 10 ml were also filtered from each of the remaining 50-ml centrifuge tubes that had been collected. Plates were incubated at 35°C for 2 h, followed by incubation at 44.5°C for 22 h. Presumptive identification of E. coli was made by observing yellow, yellow-brown, or yellow-green colonies after exposure of the filter to 2% urea (pH 3.5). E. coli levels exceeded the EPA limit for acceptable recreational water on 12 of the 17 days tested (Table 1). These samples reflected a higher proportion of out-of-limit days than the proportion reported by the City of Milwaukee Health Department for the season.

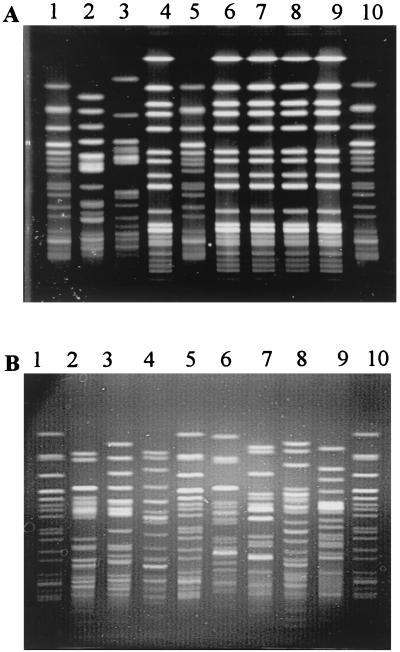

Isolates from water samples were analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (n = 170) to determine and compare the genetic profiles of strains isolated from beach water. This technique is the “gold standard” for molecular typing methods to evaluate epidemiologically related, or clonal, strains that are genetically indistinguishable and presumed to be derived from a common parent (9, 19, 27). Fifteen to 20 well-isolated colonies, presumptively identified as E. coli, were chosen from each of nine water samples. Conditions at the sampling site for each collection date varied in water temperature, amount of rainfall in the previous 24 h, and number of days since the last CSO. Each isolate was obtained from a separate primary m-TEC agar plate and grown overnight in Luria broth at 37°C for PFGE analysis according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pulse Net protocol (10, 11). Identical PFGE banding patterns were found for three or more isolates from a single sample date and on consecutive days, indicating the presence of clonal populations of isolates (Table 1; Fig. 1A). In all, four groups of isolates were identified as clonal (n = 34). The remaining isolates (n = 136) each gave a unique PFGE pattern (Table 1; Fig. 1B). The unique PFGE patterns were analyzed using Bionumerics version 2.0 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium), and the Dice coefficient for band pattern similarity ranged from 95 to 35%.

FIG. 1.

Representative agarose gel showing PFGE patterns of XbaI-digested genomic DNAs of presumptive E. coli isolates. (A) Isolates from beach water samples collected on 18 July 2000. Lanes 2 and 3, unique patterns; lanes 4 and 6 to 9, identical patterns; lanes 1, 5, and 10, E. coli O157:H7 G5244 molecular weight markers. (B) Isolates from beach water samples collected on 20 July 2000. Lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 9, unique patterns; lanes 1, 5, and 10, E. coli O157:H7 G5244 molecular weight markers.

To determine the expected diversity of PFGE patterns in known sources of fecal pollution, PFGE was performed on isolates obtained by the same microbiological protocol from sewage treatment plant influent (n = 60) and from ring-billed gull droppings (n = 40). Isolates from sewage treatment plant influent were obtained from four flow-weighted samples collected over 24 h on four dates (31 July, 11 July, 11 August, and 13 August 2000). The isolates from ring-billed gulls were collected from fecal dropping collected at South Shore Beach on 17 different days during August and September 2000, and one isolate per sample was obtained. Bacterial strains from these sources produced 96 unique PFGE patterns, with one duplicate pattern found in isolates from sewage treatment plant influent and three duplicate patterns found in isolates from gull droppings. Identical PFGE patterns were not observed for more than two isolates from the same source. This wide range of PFGE patterns is expected for E. coli isolates obtained from feces-contaminated water in the absence of replication in the environment. These findings are consistent with the reported high level of genetic diversity of natural populations of E. coli in hosts (12, 14, 26, 31). Most genotypic characterization of E. coli by PFGE has been limited to tracing clinical isolates for epidemiological purposes or surveillance and investigation of outbreaks of E. coli O157:H7. Even within this subset of E. coli strains, however, extensive genetic diversity has been reported (2, 15, 17, 22). The presence of isolates with clonal PFGE patterns (three or more isolates from a single sample date) in water samples, which were not found in isolates obtained directly from known sources of fecal contamination, indicates that the clonal isolates may propagate at the sampling site.

Further biochemical testing was performed on isolates from recreational water samples and the two known sources to confirm that they had been correctly identified as E. coli. Isolates were tested for indole production and β-glucuronidase activity using EC medium containing 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide (MUG) (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.). β-Glucuronidase activity has been shown to be highly specific to E. coli (3, 20). Other environmental bacteria with β-glucuronidase activity include strains of Enterobacter cloacae and Citrobacter freundii, but they are commonly negative for indole production (3, 20). Kluyvera spp. also demonstrate β-glucuronidase activity and are positive for indole production but, in one study, represented only 1.7% of the positive isolates from water samples (3).

The four groups of clonal isolates from water samples were found to be members of the family Enterobacteriaceae but not E. coli (Table 2). One group of isolates from the 3 July sample was positive for the production of indole and produced very weak urease reactions when they were retested using urea slants (Remel). The remaining three groups of isolates with clonal patterns were negative for indole production and confirmed to be urease negative. The identities of these organisms were determined using the API 20E system (bioMerieux, Lyon, France), and each group of clonal isolates produced identical API 20E profiles. Five hundred base pairs of the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced from one isolate from each group. The API 20E identification was in agreement with the 16S rRNA gene sequence identifiction using BLAST 2.2.1 (1), with the exception of that from a single strain of Enterobacter cloacae isolated on 3 July. All of the clonal isolates were negative for β-glucuronidase activity, demonstrating that this biochemical test is critical for distinguishing E. coli from other FC that may be misidentified using other methods.

TABLE 2.

Biochemical profiles of clonal isolates and identification by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

| Sample date(s) in 2000 (mo/day) | PFGE pattern type(s) (no. of isolates) | Organism idenificationa | Urease activity | β-Glucuronidase activity | Indole production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7/3 | A | Klebsiella oxytoca | + (weak) | 0 | + |

| 7/3 | B | Enterobacter cloacae | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7/17 and 7/18 | C | Enterobacter cloacae | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8/15 | D | Citrobacter freundii | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All dates | Unique patterns (112) | Escherichia colib | 0 | + | + |

Identification by API 20E biochemical testing and by 16S rRNA gene sequencing for one isolate from each clonal-pattern group. All organisms grew at 44.5°C and exhibited β-galactosidase activity as determined by an o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside reaction in the API 20 test.

Identification by 16S rRNA gene sequencing for 3 isolates of 112 that were MUG positive and indole positive.

Of the 136 isolates from water samples with unique PFGE patterns, 112 isolates were confirmed to be E. coli using API 20E biochemical testing. All of the confirmed E. coli isolates and two isolates identified as Kluyvera spp. were found to be positive for β-glucuronidase activity and indole production. The remaining isolates with unique patterns were negative for β-glucuronidase activity and identified as inactive E. coli (n = 2) C. freundii (n = 4), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 1), Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 5), and Enterobacter cloacae (n = 10) with API 20E profiles.

Isolates from sewage treatment plant influent and gulls were also tested for β-glucuronidase activity and indole production and confirmed by the API 20E system. A lower rate of false positives was found for the isolates from known sources than was found for the isolates from water samples; 90 of the isolates were positive for β-glucuronidase activity and indole production and confirmed to be E. coli by API 20E profiling. Two isolates of Kluyvura spp. were also identified. The remaining eight isolates were negative for β-glucuronidase activity; the API 20E system identified them as Enterobacter cloacae (n = 4), Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 3), and C. freundii (n = 1). The overall rate of false-positive results for isolates from known sources was 10%, which is similar to the reported false-positive rate reported by the EPA for the E. coli enumeration method employed in this study (30). In contrast, 100% of the clonal isolates were misidentified as E. coli, resulting in a false-positive rate of 31.2% for E. coli in the water samples.

The clonal populations of bacteria which were found to be FC other than E. coli provide strong evidence that these organisms may replicate in the environment. Given the reported diversity of E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria in natural populations, it is unlikely that these strains are representative of fecal pollution that generally originates from hundreds (e.g., gulls) or hundreds of thousands (e.g., human sewage) of hosts. This study may underestimate the occurrence of clonal FC populations, as only those isolates meeting the criteria of EPA's original method to detect E. coli were assessed by PFGE. This is an important consideration if FC are used as an indicator, since it is likely the other strains of Klebsiella, Citrobacter, and Enterobacter that are urease positive may also falsely increase indicator levels due to environmental replication. In contrast, we found that E. coli, confirmed by biochemical testing, produced a wide range of PFGE patterns, similar to the diversity of PFGE patterns found in E. coli isolates from known host sources. This suggests that E. coli is more representative of fecal contamination events than FC.

These data support the idea that E. coli is a better indicator of fecal pollution than FC. However, accurate identification is necessary to use this organism for recreational water quality monitoring. Including β-d-galactosidase activity and β-d-glucuronidase activity in E. coli, identification criteria have proven to be effective in E. coli detection (7, 8). A modified procedure recommended by the U.S. EPA incorporates this activity as part of a one-step method (30). Enterobacteriaceae found to be clonal populations in the environment are clearly distinguished from E. coli based on these criteria and are therefore excluded from presumptive identification as E. coli. The specificity of the MUG test cannot be estimated since isolates negative for urease production were initially selected. However, in the course of isolation of strains from recreational water, we have found that, out of 450 thermotolerent, lactose-fermenting, MUG-positive organisms, only 1 isolate was indole negative. This was identified as Salmonella spp. with an atypical lactose reaction. For the 206 MUG-positive, indole-positive isolates that we tested by the API 20E system, we found 4 isolates that were identified as Kluyvera spp., similar to the results of a previous study (3).

Contamination of recreational water by fecal pollution is a serious public health concern, and monitoring for actual pathogens is not feasible. We need to rely on an indicator organism that will not replicate in the environment and is easy to detect. Despite the limitations of E. coli, using it as an indicator organism may be better than other methods currently in use. We did not detect E. coli replication in the environment; however, the fact that we found a high occurrence of FC replication warrants further investigation of the environmental fate of E. coli in temperate-zone freshwaters. Whether E. coli grows or just survives and accumulates remains a point of discussion, but we found PFGE a useful tool to clearly distinguish clonal populations from the expected profile diversity in actual fecal pollution sources.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Paddock of the University of Wisconsin—System Water Institute and the U.S. Geological Service for providing the real-time monitoring data, Steve Gradus and Ajaib Singh of the City of Milwaukee Health Department for providing water quality data, and Andrew Holland from our laboratory for technical assistance. We also thank Brian Kinkle for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewage District (project number 053581-2211).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender J B, Hedberg C W, Besser J M, Boxrud D J, MacDonald K L, Osterholm M T. Surveillance for Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in Minnesota by molecular subtyping. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1525–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708073370604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner K P, Rankin C C, Roybal Y R, Stelma G N, Jr, Scarpino P V, Dufour A P. New medium for the simultaneous detection of total coliforms and Escherichia coli in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3534–3544. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3534-3544.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byamukama D, Kansiime F, Mach R L, Farnleitner A H. Determination of Escherichia coli contamination with chromocult coliform agar showed a high level of discrimination efficiency for differing fecal pollution levels in tropical waters of Kampala, Uganda. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:864–868. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.2.864-868.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrillo M, Estrada E, Hazen T C. Survival and enumeration of the fecal indicators Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Escherichia coli in a tropical rain forest watershed. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:468–476. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.2.468-476.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dufour A P. Bacterial indicators of recreational water quality. Can J Public Health. 1984;75:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckner K F. Comparison of membrane filtration and multiple-tube fermentation by the Colilert and Enterolert methods for detection of waterborne coliform bacteria, Escherichia coli, and enterococci used in drinking and bathing water quality monitoring in southern Sweden. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3079–3083. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.3079-3083.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edberg S C, Allen M J, Smith D B The National Collaborative Study. National field evaluation of a defined substrate method for the simultaneous enumeration of total coliforms and Escherichia coli from drinking water: a comparison with the standard multiple-tube fermentation method. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1595–1601. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.6.1595-1601.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenstein B I. New molecular techniques for microbial epidemiology and the diagnosis of infectious diseases. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:595–602. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foodborne and Diarrheal Diseases, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One-day (24–48 h) standardized laboratory protocol for molecular subtyping Escherichia coli O157:H7 by pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautom R K. Rapid pulse-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2977–2980. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2977-2980.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon D M, Lee J. The genetic structure of enteric bacteria from Australian mammals. Microbiology. 1999;145:2673–2682. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-10-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardina C M, Fujioka R S. Soil: the environmental source of Escherichia coli and enterococci in Hawaii's streams. Environ Toxicol Water Quality. 1991;6:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartl D L, Dykhuizen D E. The population genetics of Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet. 1984;18:31–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.18.120184.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heir E, Lindstedt B A, Vardund T, Wasteson Y, Kapperud G. Genomic fingerprinting of shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains: comparison of pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and fluorescent amplified-fragment-length polymorphism (FAFLP) Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125:537–548. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800004908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimenez L, Muniz I, Toranzos G A, Hazen T C. Survival and activity of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli in tropical freshwater. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;67:61–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb04955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause U, Thomson-Carter F M, Pennington T H. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and comparison with that by bacteriophage typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:959–961. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.959-961.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levesque B, Brousseau P, Simard P, Dewailly E, Meisels M, Ramsay D, Joly J. Impact of the ring-billed gull (Larus delawarensis) on the microbiological quality of recreational water. Appl Environ Mircobiol. 1993;59:1228–1230. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1228-1230.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olive D M, Bean P. Principles and applications of methods for DNA-based typing of microbial organisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1661–1669. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1661-1669.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez J L, Berrocal C I, Berrocal L. Evaluation of a commercial β-glucuronidase test for the rapid and economical identification of Escherichia coli. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;61:541–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruss A. Review of epidemiological studies on health effects from exposure to recreational water. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:1–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice D H, McMenamin K M, Pritchett L C, Hancock D D, Besser T E. Genetic subtyping of Escherichia coli O157 isolates from 41 Pacific Northwest USA cattle farms. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:479–484. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivera S C, Hazen T C, Toranzos G A. Isolation of fecal coliforms from pristine sites in a tropical rain forest. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:513–517. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.513-517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roll B M, Fujioka R S. Sources of faecal indicator bacteria in a brackish tropical stream and their impact on recreational water quality. Water Sci Technol. 1997;35:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solo-Gabriele H M, Wolfert M A, Desmarais T R, Palmer C J. Sources of Escherichia coli in a coastal subtropical environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:230–237. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.230-237.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Souza V, Rocha M, Valera A, Eguiarte L E. Genetic structure of natural populations of Escherichia coli in wild hosts on different continents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3373–3385. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3373-3385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulse-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toranzos G A, McFeters G A. Detection of indicator microorganisms in environmental freshwaters and drinking waters. In: Hurst C J, Knudsen G R, McInerney M J, Stetzenbach L D, Walter M V, editors. Manual of environmental microbiology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. pp. 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for bacteria–1986. EPA-440/5–84/002. Washington, D.C.: Office of Water Regulations and Standards, Criteria and Standards Division; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Improved enumeration methods for recreational water quality indicators: enterococci and Escherichia coli. EPA/821/R-97/004. Washington, D.C.: Office of Science and Technology; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whittam T S, Ochman H, Selander R K. Multilocus genetic structure in natural populations of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1751–1755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]