Abstract

Introduction/Aims

Data regarding weight, height/length, and growth status of patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) who have received only supportive care are limited. This cross‐sectional study describes these measurements in patients with Type 1 and Types 2/3 SMA and compares them with reference values from typically developing children.

Methods

Retrospective baseline data from three sites in the Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research Network (Boston, New York, Philadelphia) were used. Descriptive statistics for weight, height/length, body mass index‐for‐age, as well as weight‐for‐length and absolute and relative deviations from reference values (ie, 50th percentile from World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control growth charts) were calculated. Furthermore, growth status was reported.

Results

A total of 91 genetically confirmed patients with SMA receiving optimal supportive care and without any disease‐modifying treatment were stratified into Types 1 (n = 28) and 2/3 SMA (n = 63). Patients with Type 1 SMA weighed significantly less (median = −7.5%) compared with reference values and patients with Types 2/3 SMA were significantly shorter (mean = −3.0%) compared with reference values. The median weight was considerably below the 50th percentile in both groups of patients, even if they received a high standard of care and proactive feeding support.

Discussion

More research is needed to understand which factors influence growth longitudinally, and how to accurately capture growth in patients with SMA. Further research should investigate the best time to provide feeding support to avoid underweight, especially in patients with Type 1, and how to avoid the risk of overfeeding, especially in patients with Types 2/3 SMA.

Keywords: body mass index, growth status, height, obesity, spinal muscular atrophy, weight

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- IQR

interquartile range

- NIV

non‐invasive ventilation

- PNCR

Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research

- SMA

spinal muscular atrophy

- SMN

survival of motor neuron

- SOC

standard of care

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. INTRODUCTION

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare, genetic, neuromuscular disorder caused by mutation or deletion of the 5q13 survival of motor neuron (SMN1) gene. 1 , 2 , 3 Loss of function of the SMN1 gene results in insufficient levels of functional SMN protein causing progressive muscle weakness. 4 , 5

Individuals with SMA can follow atypical growth trajectories, a phenomenon which, among others, may be the result of bulbar dysfunction from muscle weakness and complications of prolonged immobility. 6 Understanding the atypical growth of patients with SMA is key to being able to deliver the best nutritional support for these patients. The data from untreated patients provide an important reference for evaluating how treatments for SMA impact the growth and nutritional support requirements of patients. While data regarding weight and height/length distribution among patients with SMA are limited, reports of both underweight 7 and overweight 8 in patients with SMA exist. Feeding and swallowing difficulties may influence low weight among patients with Type 1 SMA, 9 , 10 , 11 whereas reduced muscle bulk contributes to low weight among patients with Types 2/3 SMA. 12 Length measurements are reported as largely normal among patients with Type 1 SMA. 13 Literature detailing length among patients with Types 2/3 SMA is limited.

This study aimed to describe the weight, height/length, and growth status in children and adolescents with SMA stratified by Type 1 and Types 2/3 in the era predating the availability of disease‐modifying treatments for SMA. Measures were compared with reference values of typically developing children.

2. METHODS

2.1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Individuals were identified through the Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research (PNCR) Network in the USA, a multicenter, observational cohort study designed to characterize patients with SMA. 14 Individuals were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (a) a genetically confirmed diagnosis of SMA, (b) aged ≤18 y at baseline visit, (c) available assessments of weight and height at baseline visit, and (d) baseline visit between 2005 and 2009. Patients using investigational therapies were excluded (see Supporting Information Appendix S1).

2.2. Study design/outcomes

Weight and height/length were assessed at baseline visit. Age‐ and sex‐specific growth charts were used as reference values as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 15 and pediatric endocrinologists in clinical practice: World Health Organization (WHO) 16 charts for patients ≤2 y of age and CDC charts for patients ≥2 y of age.

Percentiles for weight, height/length, weight‐for‐length, and body mass index (BMI)‐for‐age were extracted according to the recommended growth charts. Absolute and relative deviations in weight, height/length, weight‐for‐length, and BMI‐for‐age were calculated by comparing the individual's measurements with the expected values defined as the age‐ and sex‐matched 50th percentile from WHO/CDC growth charts.

2.3. Growth status

Individuals' weight‐for‐length Z‐scores (for patients 0–2 y of age) and BMI‐for‐age percentiles (for patients 2–18 y of age) were used to categorize patients' growth status as underweight, normal, overweight, or obese based on reference standards from the WHO and CDC. Categories from the WHO and CDC reference standards were combined as they differed slightly (see Supporting Information Appendix S1).

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed for the overall sample and stratified by age and SMA type. Means (SD) are reported if variables are normally distributed and medians (interquartile range [IQR]) if they are non‐normally distributed. Statistical tests were performed to test if distributions deviated from zero. If values were normally distributed, a one‐sample two‐tailed t‐test was performed. Otherwise, a Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was used (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). Normality was tested using a Shapiro–Wilk test with alpha = 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 91 patients were included and results were stratified into Type 1 (n = 28) and Types 2/3 SMA (n = 63; Table 1). Median age was 1.1 and 6.8 y for the Type 1 and Types 2/3 patients, respectively. Sex was evenly distributed among both SMA types. For further baseline characteristics, refer to Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline patient characteristics stratified by SMA type and for the overall sample

| Characteristic | Type 1 SMA (n = 28) | Type 2/3 SMA (n = 63) | Overall sample (N = 91) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at visit (y) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1.1 (0.5–1.8) | 6.8 (4.0–11.4) | 5.5 (1.7–9.7) |

| Min–max | 0.2–15.5 | 0.9–18.8 | 0.2–18.8 |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Female | 14 (50) | 33 (52) | 47 (52) |

| Age at onset (mo) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 12 (8–18) | 8 (4–12) |

| Min–max | 0.5–7 | 3–96 | 0.5–96 |

| SMN2 copy number (%) | |||

| n | 27 (96) | 63 (100) | 90 (99) |

| 2 | 20 (71) | 1 (2) | 21 (23) |

| 3 | 7 (25) | 53 (84) | 60 (66) |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 8 (13) | 8 (9) |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| NIV at visit (%) | |||

| n | 27 (96) | — | — |

| Yes | 13 (46) | — | — |

| No | 14 (50) | — | — |

| Feeding support at visit (%) | |||

| n | 27 (96) | 53 (84) | 80 (88) |

| Yes | 17 (61) | 7 (11) | 24 (26) |

| No | 10 (36) | 46 (73) | 56 (62) |

Note: Number of patients (n) is stated if data were incomplete. Limited information (n = 1) about NIV in patients with Types 2/3 SMA was available and was therefore not presented in this table (dashes). Median (IQR) and min–max were reported, because variables were not normally distributed in at least one stratum.

3.2. Absolute weight and height/length, and percentiles

Weight and height/length measurements were measured for the overall sample and stratified by SMA type. Absolute values and percentiles can be found in Supporting Information Table S1. Median weight percentile was 26.4 for Type 1 and 24.2 for Types 2/3 patients. Median height/length percentile was greater in patients with Type 1 (53.9) compared with those with Types 2/3 SMA (29.9).

3.3. Relative and absolute weight and height/length deviations from reference values

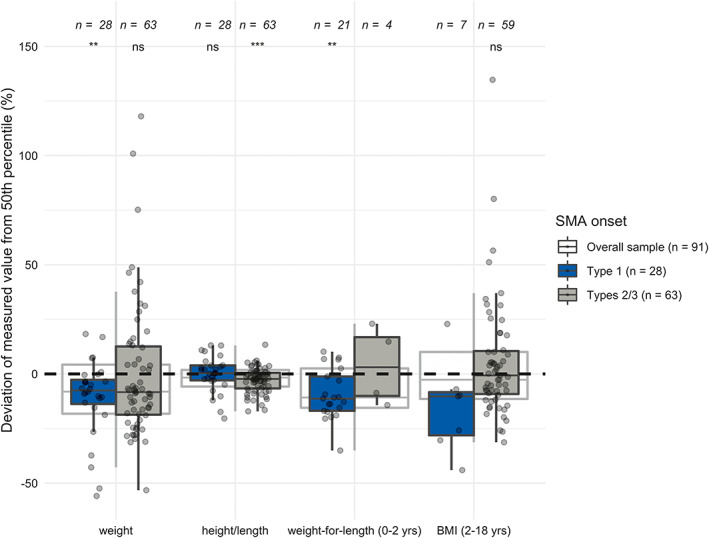

Overall, patients with SMA weighed significantly less (p = .007) and were significantly shorter (p = .004) relative to the age‐ and sex‐matched reference values of typically developing children (Table 2; Figure 1). Patients with Type 1 SMA weighed significantly less (p = .002) compared with reference values (Supporting Information Figure S1). The weight deviation for patients with Types 2/3 SMA was not significant (p = .183). Patients with Type 1 SMA did not deviate significantly from the 50th height/length percentile (p = .954), but patients with Types 2/3 SMA were slightly shorter than expected from reference values (p < .001; Supporting Information Figure S2).

TABLE 2.

Relative and absolute deviations of measured weight, height/length, weight‐for‐length (0–2 y) and BMI‐for‐age (2–18 y) from reference values stratified by SMA type and for the overall sample

| Weight and height/length | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 SMA (n = 28) | Types 2/3 SMA (n = 63) | Overall sample (N = 91) | |

| Relative weight deviation (%) | |||

| Median (IQR) | −7.5 (−15.5 to −3.4) | −8.3 (−18.9 to 12.1) | −8.1 (−18.4 to 4.2) |

| Min–max | −55.9 to 18.3 | −53.3 to 118.0 | −55.9 to 118.0 |

| Z value | 69 | 813 | 1407 |

| Absolute weight deviation (kg) | |||

| Median (IQR) | −0.6 (−1.7 to −0.2) | −1.4 (−5.4 to 1.9) | −1.1 (−4.8 to 1.0) |

| Min–max | −27.8 to 2.3 | −20.5 to 51.4 | −27.8 to 51.4 |

| Relative height/length deviation (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | −0.1 (8.2) | −3.0 (5.8) | −2.1 (6.7) |

| t statistics (df) | −0.0582 (27) | −4.01 (62) | 2.9195 (90) |

| Absolute height/length deviation (cm) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.2 (−2.0 to 2.4) | −2.4 (−9.0 to 0.4) | −1.6 (−7.8 to 1.4) |

| Min–max | −32.8 to 12.0 | −25.2 to 17.7 | −32.8 to 17.7 |

| Type 1 SMA | Types 2/3 SMA | Overall sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 y (n = 21) | 2–18 y (n = 7) | 0–2 y (n = 4) | 2–18 y (n = 59) | 0–2 y (n = 25) | 2–18 y (n = 66) | |

| Relative weight‐for‐length deviation (%) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | −9.4 (11.5) | — | 3.7 (18.0) | — | −7.3 (13.2) | — |

| Absolute weight‐for‐length deviation (kg) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.8 (1.1) | — | 0.4 (1.8) | — | −0.6 (1.3) | — |

| Relative BMI‐for‐age deviation (%) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | — | −10.3 (−30.4 to −9.7) | — | −0.7 (−9.6 to 10.1) | — | −2.7 (−12.0 to 10.1) |

| Min–max | — | −44.0 to 22.9 | — | −31.3 to 134.7 | — | −44.0 to 134.7 |

| Absolute BMI‐for‐age deviation (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | — | −2 (−6.1 to −1.5) | — | −0.1 (−1.7 to 1.7) | — | −0.4 (−2.1 to 1.7) |

| Min–max | — | −8.0 to 3.8 | — | −5.5 to 20.8 | — | −8.0 to 20.8 |

Note: Mean (SD) and t statistics (df) were reported for variables that were normally distributed in all strata (according to Shapiro–Wilk Test with alpha = 0.05); median (IQR) and min–max for variables not normally distributed in at least one stratum. Note: Dashes indicate data were not calculated (see Supporting Information Appendix S1).

Abbreviation: df, degrees of freedom.

FIGURE 1.

Deviations of measured weight, height/length, weight‐for‐length (0–2 y), and BMI‐for‐age (2–18 y) in percent from the 50th percentiles in the overall sample, patients with type 1 SMA and patients with types 2/3 SMA

3.4. Growth status

Most patients with Type 1 SMA were categorized as normal weight, some were underweight (32.1%) or overweight (3.6%), and none were obese. Over half of patients with Types 2/3 SMA were categorized as normal weight; the remaining were underweight, overweight, or obese (Supporting Information Table S1). Importantly, a total of 61% of patients with Type 1 and 11% with Types 2/3 SMA received feeding support (Supporting Information Table S2). The results for relative weight‐for‐length and BMI‐for‐age can be found in Table 2, Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4.

4. DISCUSSION

Our main findings show that median weight is lower among individuals with Type 1 SMA and height is lower in individuals with Types 2/3 SMA compared with reference values. Although the majority of patients were within the predefined “normal” range (see Supporting Information Appendix S1), the median weight was considerably below the 50th percentile in patients with Type 1 and Types 2/3 SMA. 13 This was the case despite them receiving a high standard of care (SOC) and proactive feeding support.

These results are similar to other reported data. 17 That study found that patients at the most severe end of the spectrum, Type 1 who required respiratory or nutritional support, had the lowest weight compared to the reference values. This aligns with our Type 1 patients' data. They also reported lower heights for patients with Type 2 SMA, but interestingly only for girls from 3 y old on. We note that none of their patients with Type 2 were receiving feeding support, whereas 11% in our mixed Type 2/3 group did so, suggesting that a greater impact on growth might be expected. In addition, our study found that weight differences were not significant in patients with Type 2/3 SMA due to higher variability between individuals. Some differences might also be explained by different techniques of length measurement, as the PNCR also allowed standing height to be captured.

This study supports the establishment of growth distributions specific to SMA, which is important as body composition differs between healthy children and patients with SMA—patients with SMA having increased fat mass and reduced lean mass. 12 , 13 , 18 However, further research is needed to understand which factors influence age‐appropriate weight increase, height/length growth, and overall growth status longitudinally, and which measures accurately capture growth. The best time point to provide feeding support to avoid underweight, particularly in patients with Type 1 SMA, and to avoid the risk of overfeeding and overweight, 12 especially in patients with Types 2/3 SMA, should be investigated. Future studies should also consider other factors that impact the growth status of patients, such as the role of additional modulating biologic or metabolic factors (ie, severe SMN protein deficiency in the periphery, mitochondrial dysfunction, or reduced insulin‐like growth factor) in isolation or conjunction with severe muscle denervation. 19

One limitation of this study is that it covers patients with visits between 2005 and 2009. Changes in SOC 20 , 21 and newly approved treatments 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 have occurred since then and may impact the growth patterns of patients with SMA. Additionally, obtaining accurate body height/length measurements may be challenging in patients with SMA due to secondary medical conditions (eg, scoliosis, contractures), which could lead to an underestimation of height/length, especially in Types 2/3 SMA. Last, the current data set may not include the most severe cases of SMA, as these patients may not have enrolled in the study due to the challenges associated with traveling for study visits or early demise.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

B.T.D. has served as an ad hoc scientific advisory board member for AveXis, Biogen, Cytokinetics, Vertex, Genentech/Roche, and Pfizer; Steering Committee Chair for Roche and DSMB member for Amicus Inc.; he has no financial interests in these companies. He has received research support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Slaney Family Fund for SMA, the Spinal Muscular Atrophy Foundation, CureSMA, and Working on Walking Fund and has received grants from Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for the ENDEAR, CHERISH, CS2/CS12 studies; from Biogen for CS11; and from Cytokinetics, Sarepta Pharmaceuticals, PTC Therapeutics, Scholar Rock, Fibrogen, and Summit. He has also received royalties for books and online publications from Elsevier and UpToDate, Inc. S.G., J.H., S.S., I.G., K.G., S.F‐R., and R.S.S., are employees of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche. R.S.F. has participated as an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by AveXis/Novartis Gene Therapies, Biogen, Catabasis, Cytokinetics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Muscular Dystrophy Association, National Institutes of Health, Lilly, ReveraGen, Roche, Sarepta, Scholar Rock, and Summit. He has received honoraria for participating in symposia and on advisory boards for these same pharmaceutical companies. The data used in this manuscript were collected prior to these engagements with Roche. He serves without compensation as an advisor to the n‐Lorem and EveryLife Foundations. His institution receives funding from Biogen for the coordination of a USA registry for SMA, iSMAC. He receives licensing fees from the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and publishing royalty fees from Elsevier. D.C.D. has served as an advisor/consultant for AveXis, Biogen, Cytokinetics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Metafora, Roche, Sanofi, Sarepta, n‐lorem Foundation and the SMA Foundation; received grants from Hope for Children Research Foundation, National Institutes of Health, SMA Foundation, Cure SMA, Glut 1 Deficiency Foundation and US Department of Defense; clinical trial funding from Biogen, Mallinckrodt, PTC, Sarepta, Scholar Rock, and Ultragenyx; and as a member of the DSMB for Aspa Therapeutics.

ETHICAL PUBLICATION STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the PNCR Network, SMA Foundation, and the families who have contributed to this research. This study is sponsored by F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland. The authors thank Michelle Kim, PhD, from MediTech Media for providing medical writing support, which was funded by F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Darras BT, Guye S, Hoffart J, et al. Distribution of weight, stature, and growth status in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy: An observational retrospective study in the United States. Muscle & Nerve. 2022;66(1):84‐90. doi: 10.1002/mus.27556

Funding information F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research (PNCR) Network. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available with the permission of the PNCR Network.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy‐determining gene. Cell. 1995;80:155‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodrigues NR, Owen N, Talbot K, Ignatius J, Dubowitz V, Davies KE. Deletions in the survival motor neuron gene on 5q13 in autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:631‐634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swoboda KJ. Of SMN in mice and men: a therapeutic opportunity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2978‐2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lorson CL, Hahnen E, Androphy EJ, Wirth B. A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6307‐6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Amico A, Mercuri E, Tiziano FD, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arnold WD, Kassar D, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy: diagnosis and management in a new therapeutic era. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51:157‐167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sproule DM, Montes J, Montgomery M, et al. Increased fat mass and high incidence of overweight despite low body mass index in patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:391‐396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moore GE, Lindenmayer AW, McConchie GA, et al. Describing nutrition in spinal muscular atrophy: a systematic review. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26:395‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Heul AMB, Cuppen I, Wadman RI, et al. Feeding and swallowing problems in infants with spinal muscular atrophy type 1: an observational study. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;7:323‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, et al. Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1027‐1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wadman RI, De Amicis R, Brusa C, et al. Feeding difficulties in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy type 2. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31:101‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sproule DM, Montes J, Dunaway S, et al. Adiposity is increased among high‐functioning, non‐ambulatory patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:448‐452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poruk KE, Davis RH, Smart AL, et al. Observational study of caloric and nutrient intake, bone density, and body composition in infants and children with spinal muscular atrophy type I. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22:966‐973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finkel RS, McDermott MP, Kaufmann P, et al. Observational study of spinal muscular atrophy type I and implications for clinical trials. Neurology. 2014;83:810‐817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 16. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/height‐for‐age, weight‐for‐age, weight‐for‐length, weight‐for‐height and body mass index‐for‐age: Methods and development. https://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/technical_report/en/. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 17. De Amicis R, Baranello G, Foppiani A, et al. Growth patterns in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bertoli S, De Amicis R, Mastella C, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy, types I and II: what are the differences in body composition and resting energy expenditure? Clin Nutr. 2017;36:1674‐1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brener A, Sagi L, Shtamler A, Levy S, Fattal‐Valevski A, Lebenthal Y. Insulin‐like growth factor‐1 status is associated with insulin resistance in young patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020;30:888‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28:103‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28:197‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. SPINRAZA® (nusinersen) US prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/209531lbl.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 23. SPINRAZA® (nusinersen) EMA prescribing information. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/004312/WC500229704.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 24. ZOLGENSMA® (onasemnogene abeparvovec‐xioi) US prescribing information. https://www.fda.gov/media/126109/download. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 25. ZOLGENSMA® (onasemnogene abeparvovec‐xioi) EMA prescribing information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zolgensma-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 26. Evrysdi (risdiplam) EMA prescribing information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product‐information/evrysdi‐epar‐product‐information_en.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- 27. Evrysdi (risdiplam). US prescribing information. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/evrysdi_prescribing.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research (PNCR) Network. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available with the permission of the PNCR Network.