Abstract

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) may be used in molecular and point-of-care diagnostics for pathogen detection. The amplification occurs under isothermal conditions using up to six primers. However, non-specific amplification is frequently observed in LAMP. Non-specific amplification has the potential to be triggered by forward and reverse internal primers. And the relatively low reaction temperature (55–65 °C) induces the secondary structure via primer–primer interactions. Primer redesign and probe design have been recommended to solve this problem. LAMP primers have strict conditions, such as Tm, GC contents, primer dimer, and distance between primers compared to conventional PCR primers. Probe design requires specialized knowledge to have high specificity for a target. In polymerase chain reaction (PCR), some chemicals or proteins are used for improving specificity and efficiency. Therefore, we hypothesized that additives can suppress the non-specific amplification. In this study, tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC), formamide, dimethyl sulfoxide, Tween 20, and bovine serum albumin have been used as LAMP additives. In our study, TMAC was presented as a promising additive for suppressing non-specific amplification in LAMP.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13206-022-00070-3.

Keywords: Additive, Loop-mediated isothermal amplification, Non-specific amplification, Tetramethylammonium chloride

Introduction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a well-established technique and is widely used in molecular biology and clinical medicine. This technique specifically amplifies a target region of a DNA sequence using two primers and Taq polymerase [1, 2]. It is carried out through three steps, such as denaturation, annealing, and extension. The process occurs as the temperature continuously changes. Complicated equipment and highly sophisticated technology are required to satisfy this. Therefore, PCR is limited to laboratories or hospitals [3, 4]. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification was devised to improve this problem. This technique can amplify nucleic acids in point-of-care testing (POCT). Therefore, it is widely used as an alternative to PCR [5–7].

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) rapidly amplifies nucleic acids using six primers. LAMP primers specifically recognize the target and improve high specificity and sensitivity. The LAMP primer consists of forward outer primer (F3), backward outer primer (B3), forward inner primer (FIP), backward inner primer (BIP), forward loop primer (LF), and backward loop primer (LB) [8–10]. FIP and BIP (approximately 40–45 nt) form the loop structure of LAMP amplicon. F3 and B3 (approximately 17–21 nt) separate the amplified DNA strands generated by FIP and BIP into single-stranded DNA. These are involved in extending the target gene. LF and LB (approximately 15–21) accelerate the LAMP reaction by enhancing loop structure formation [5]. Amplification is performed under isothermal conditions using Bst polymerase [10–13]. LAMP produces 109 copies within 1 h without a separate DNA denaturation process. And does not require any special equipment, making it suitable for point-of-care testing (POCT) [5, 9, 14].

However, non-specific amplification is sometimes observed in LAMP. The low temperature induces the secondary structure and primer dimer due to the interaction between primers [15–19]. To solve this problem, primer redesign [20–22] and probe design [15, 23–25] are recommended. Primer redesign is limited due to stringent conditions, such as Tm, GC contents, primer dimer, and distance between primers [9]. In particular, LF and LB may not be designed according to the target sequence. FIP and BIP are highly complicated sequences containing the F2/B2 and F1c/B1c regions. Therefore, they have the possibility of forming a primer dimer. Probe design must be designed to have high specificity and therefore requires expertise [5, 9].

Some chemicals and proteins enhance specificity in PCR and isothermal amplification assays [26–30]. We hypothesized that some chemicals and proteins could suppress non-specific amplification. Five additives, such as tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC), formamide, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Tween 20, and bovine serum albumin (BSA), are used for experiments.

In this study, TMAC was proposed as an alternative to overcome the technical limitations of LAMP. To the best of our knowledge, the correlations between TMAC and non-specific amplification have not been reported in the literature. We report a novel alternative to suppress non-specific amplification without primer redesign and probe design. As a result, expected that LAMP will have high specificity and be utilized in various fields.

Experimental Section

Materials

Isothermal amplification buffer (10×, containing 2 mM MgSO4 and 0.1% Tween 20), 10 mM deoxynucleotide (dNTP) solution, WarmStart RTx Reverse Transcriptase, and Bst 2.0 Warmstart DNA polymerase were purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain, Tween 20, dimethyl sulfoxide, formamide, and tetramethylammonium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The LAMP primers were synthesized by Bioneer (Seoul, Korea). Diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water (DEPC-water) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). BSA was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Seoul, Korea). SARS-CoV-2 (NR-55245) was provided by BEI Resource (Manassas, Virginia, USA). RNA was isolated from the influenza viruses using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany).

Primer Design for SARS-CoV-2

RT-LAMP primers were designed with Primer Explorer V5 software (http://primerexplorer.jp/lampv5e/l). The RdRp region of ORF1 ab was selected to specifically recognize SARS-CoV-2. This region is known for highly conserved genes and World Health Organization is recommended for use [31, 32]. Six genes (MT232870.1, MT127116.1, MT066158.1, MT050415.1, MT050417.1, and MN970004.1) were arbitrarily selected from the NCBI database. The formation of primer dimers was evaluated to minimize false positives. Cross-reactivity was analyzed in silico with pathogens with potential for human respiratory disease. The designed primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specific LAMP primer for SARS-CoV-2

| Primer | length | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| F3 | 18 | TTTGTCAAGCTGTCACGG |

| B3 | 18 | ACAGCATCGTCAGAGAGT |

| FIP | 45 | GACACTCATAAAGTCTGTGTTGTTTAATGCACTTTTATCTACTGA |

| BIP | 46 | AGAGATGTTGACACAGACTTTGTGTCATTGAGAAATGTTTACGCAA |

| LF | 21 | TAACGGCTATTCATACAGGCG |

| LB | 18 | AATGAGTTTTACGCATAT |

RT-qLAMP Reaction Optimization

RT-qLAMP Assay

The final volume was 20 µL. RT-qLAMP reagents consist of 10× isothermal amplification buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, and 0.1% Tween 20], 0.3 mM each of dNTP, 4 U WarmStart RTx Reverse Transcriptase, 8 U Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase, 1× SYBR Green I and primer mix. The primer mix consists of 0.2 µM F3 and B3, 1.6 µM FIP and BIP, and 0.4 µM LF and LB. After preparing the LAMP reagent, 5 µL template RNA is added. For negative sample, use the DEPC-water instead of template RNA. The RT-qLAMP assays were carried out in 0.2 ml PCR tubes or 0.2 ml 96-well plates in a Bio-Rad T100 thermocycler (Hercules, CA, USA). The reaction was performed continuously at 60 °C for 60 min. The fluorescence data were recorded every 1 min. All experiments were terminated by enzymatic inactivation at 80 °C and were repeated three times. All data were expressed as the mean Ct and standard deviation of three experiments.

Analyzation of the Sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 Primer

Limit of detection (LoD) was analyzed to evaluate the sensitivity of the primers. A standard curve was obtained through RT-qPCR by serial dilution of the RdRp plasmid. The copies number of the RNA was determined by comparing the standard curve. RNA was serially diluted 10-fold (6.8 × 106 to 6.8 × 101 copies/µL) based on the determined copy number and used for RT-qLAMP.

Evaluation of Overall Reactivity by Additive Treatment

Five additives were tested to suppress the non-specific amplification. Various concentrations of additive were used in the experiment (20–60 mM TMAC, 2.5–7.5% (v/v) formamide, 2.5–7.5% (v/v) DMSO, 0.5–2% (v/v) Tween 20, and 0.1 to 0.5 mg/ml BSA). Samples without additives were called control. The template (6.8 × 103 copies/µl) was prepared at a concentration 10 times higher than the detection limit. The results were analyzed using the threshold cycle (Ct) value. Ct is defined as the point where the fluorescence signal crosses a threshold [33]. A low value of Ct is observed with a large amount of target. The concentration of target can be relatively inferred via this value [34]. ΔCt is the difference between the Ct values of the positive and negative samples. The value is an indication to infer the reliability of the results. ΔCt was used to evaluate the correlation between additive and non-specific amplification. The values were calculated using Eq. 1. Ct(negative) is the threshold of condition without template. Ct(positive) is the threshold of condition with template. Ct(negative) and Ct(positive) were measured according to the additive. In addition, Ct(positive) was analyzed to evaluate LAMP reactivity. The data were collected via RT-qLAMP.

| 1 |

Results and Discussion

Evaluation of LoD for SARS-CoV-2 Primer

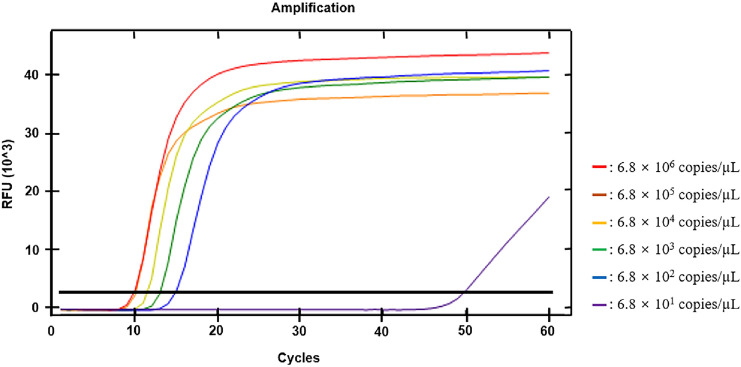

LoD is defined as the lowest concentration at which a positive or negative sample can be reliably distinguished [35, 36]. In this study, the lowest concentration belonging to the 95% confidence level for the detection of the target was determined as LoD. Positive signal was confirmed at all concentrations except 6.8 × 102 copies/µL and 6.8 × 101 copies/µL in 20 out of 20 trials (Fig. 1). For 6.8 × 102 copies/µL, a positive signal was obtained only in 19 out of 20 trials. For 6.8 × 101 copies/µL, a positive signal was obtained only in 15 out of 20 trials. Therefore, LoD was determined to be 6.8 × 102 copies/µL, which is the lowest concentration among the concentrations belonging to the 95% confidence level.

Fig. 1.

Sensitivity analysis of SARS-CoV-2 primers. 6.8 × 106 copies/µL to 6.8 × 101 copies/µL use to analyze LoD. The lowest concentration detected in 20 out of 20 trials was 6.8 × 102 copies/µL. The LoD determined this concentration

Analysis of Non-specific Amplification According to Additive

TMAC

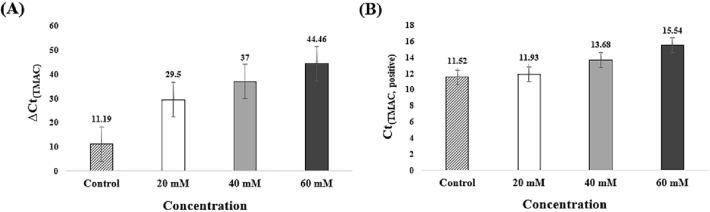

ΔCt(TMAC) and Ct(TMAC, positive) were obtained through RT-qLAMP. This value was compared with ΔCt(control) and Ct(control, positive). (Fig. 2). ΔCt(Control) was measured to be 11.19 (Fig. 2(A)). ΔCt(TMAC) was measured to be 29.5, 37, and 44.46 with increasing TMAC concentration. Non-specific amplification was not observed with 60 mM TMAC (Fig. S1). Therefore, the Ct(60 mM TMAC, negative) value of 60 was assumed. TMAC effectively suppressed non-specific amplification all concentration. It can be inferred that the inhibition of non-specific amplification according to the TMAC concentration. Ct(positive) was measured to evaluate the reactivity (Fig. 2(B)). Ct(TMAC, positive) is obtained increased value according to increasing concentration. There was no significant difference between Ct(20 mM TMAC, positive) and Ct(control, positive). Ct(40 mM TMAC, positive) was delayed by 2 min, and Ct(60 mM TMAC, positive) was delayed by 4 min. A high concentration of TMAC has the potential to suppress the LAMP. There is no significant effect on the overall reaction. This result is caused by the non-polar characteristic of TMAC. TMAC preferentially binds to the hydrated AT base pair via the attraction of the non-polar arm of the alkylammonium ion [18, 37]. Thus, it contributes to the stability of GC base pairs and adjacent AT base pairs [18]. This property increases the DNA melting temperature and reduces the mismatch of DNA or RNA [18, 37]. LAMP reaction is affected by 40 mM and 60 mM TMAC. However, Ct(20 mM TMAC, positive) has a similar value to Ct(control, positive). Also ΔCt(20 mM TMAC) increased by 2.63 times compared to ΔCt(control). ΔCt(40 mM TMAC) increased by 1.25 times and ΔCt(60 mM TMAC) increased by 1.2 times compared to the previous concentration. 20 mM TMAC exerts a dramatic effect without suppressing LAMP reaction. Therefore, the optimal concentration was determined the 20 mM TMAC.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of ΔCt and Ct(TMAC, positive) according to TMAC concentration. Mean Ct and standard deviation of three tested experiments. A Comparison of ΔCt(TMAC) and ΔCt(control). ΔCt(TMAC) increased with increasing TMAC concentration. A difference between ΔCt(control) and ΔCt(TMAC) is more than 30 min. B Ct(2.5% TMAC, positive) and Ct(5% TAMC, positive) did not show a significant difference with Ct(control, positive). However, Ct(7.5% TAMC, positive) differed from Ct(control, positive) by 4 min

The effects of TMAC were confirmed through concentration screening in non-specific amplification. Therefore, further experiments were performed at concentrations above 60 mM TMAC. In the positive sample, the standard deviation of 20 mM to 60 mM TMAC was measured to be less than 0.4, but the standard deviation increased to about 1.8 in 80 mM and 100 mM TMAC (Fig. S1(B)). The reproducibility decreased with increasing concentration in positive samples. Non-specific amplification was not observed even in 80 mM and 100 mM TMAC (Fig. S1(C)). Although non-specific amplification was not observed, reactivity was significantly decreased and reproducibility was not ensured. Therefore, concentrations above 80 mM are of limited use.

Formamide

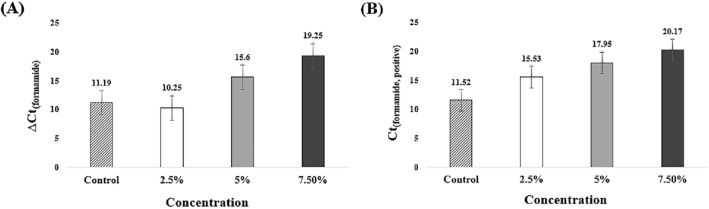

ΔCt(formamide) value was calculated to analyze the correlation between formamide and non-specific amplification (Fig. 3(A)). ΔCt(2.5% formamide) increased by 0.94 compared to ΔCt(control). Ct(2.5% formamide, negative) was measured to be 25.78, Ct(control, negative) was measured to be 22.71 (Fig. S2). There was no significant difference. However, 5% formamide was observed to suppress non-specific amplification. ΔCt(5% formamide) was measured to be 15,6, and ΔCt(7.5% formamide) was measured to be 19.25. All ΔCt(formamide) was increased compared to ΔCt(control). Ct(5% formamide, negative) was measured to be 33.55 and Ct(7.5% formamide, negative) was measured to be 39.42 (Fig. S2). Formamide suppressed non-specific amplification. However, Ct(5% formamide, positive) and Ct(7.5% formamide, positive) were measured to be 17.95 and 20.17 (Fig. 3(B)). The detection rate was significantly delayed compared to control. This result is caused by the involvement of formamide on the secondary structure. Formamide binds to the minor or major groove and induces instability in the double helix [38]. Formamide interferes with secondary structure formation. However, the LAMP amplicon has a secondary structure and the amplification efficiency is inhibited by formamide. Consequently, formamide is limited to use.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of ΔCt and Ct(formamide, positive) according to formamide concentration. Mean Ct and standard deviation of three tested experiments. A Comparison of ΔCt(formamide) and ΔCt(control). ΔCt(2.5% formamide) decreased by 0.94 than ΔCt(control). However, ΔCt(5% formamide) and ΔCt(2.5% formamide) have increased values than ΔCt(control). B The value of Ct(positive) increased with increasing formamide concentration. Ct(7.5% formamide, positive) delayed up to 9 min by Ct(control, positive)

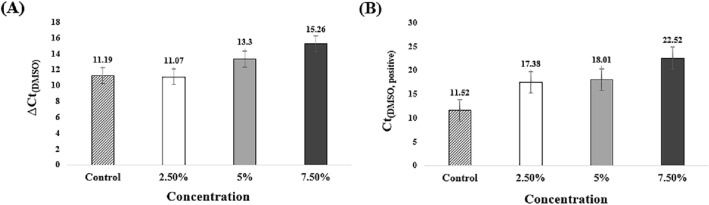

DMSO

ΔCt value was calculated according to the DMSO concentration (Fig. 4(A)). ΔCt(2.5% DMSO) was not significantly different from ΔCt(control). A high concentration of DMSO increases the ΔCt value (ΔCt(5% DMSO) is 13.3 and ΔCt(7.5% DMSO) is 15.26. However, it is delayed up to 4.07 and cannot be effectively suppressed. Ct (positive) has a higher value as the concentration of DMSO increases (Fig. 4(B)). A high concentration of DMSO inhibits the activity of Bst polymerase [22]. DMSO was excluded by suppressing the LAMP. Amplification curves of control and DMSO-treated conditions are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S3.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of ΔCt and Ct(DMSO, positive) according to DMSO concentration. Mean Ct and standard deviation of three tested experiments. A ΔCt(2.5% DMSO) did not show a significant difference with ΔCt(control). The values of ΔCt(5% DMSO) and ΔCt(7.5% DMSO) increased compared to ΔCt(control). B All concentrations of Ct(DMSO, positive) were observed increased values than that of Ct(control, positive). Ct(7.5% DMSO, positive) was delayed to 10 min by Ct(control, positive)

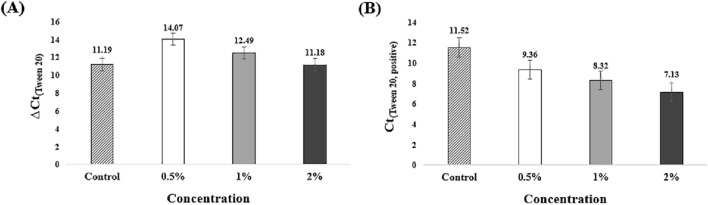

Tween 20

ΔCt(Tween 20) is decreased the value as an increased Tween 20 concentration (Fig. 5(A)). ΔCt(0.5% Tween 20) and ΔCt(1% Tween 20) had increased values than ΔCt(control). ΔCt(2% Tween 20) was measured as 11.18 and was similar to ΔCt(control). However, it can be inferred that Tween 20 is not effective for non-specific amplification by comparing Ct(Tween 20, negative). Ct(0.5% Tween 20, negative) was measured to be 23.43, and Ct(1% Tween 20, negative) was measured to be 20.81 (Fig. S4). Non-specific amplification was detected similarly to Ct(control, negative). Ct(2% Tween 20, negative) was measured to be 18.31 and detected earlier than the control. Ct(Tween 20, positive) tends to increase at high concentration (Fig. 5(B)). Appropriate concentrations such as 0.5% or 1% enhance the reactivity. However, Fig. S4 shows that high concentrations of Tween 20 simultaneously enhance non-specific amplification. Tween 20 increases the probability of DNA or RNA mismatches [39, 40]. Therefore, it is recommended to use only a small amount of the LAMP reagent rather than being used as an additive.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of ΔCt and Ct(Tween 20, positive) according to Tween 20 concentration. Mean Ct and standard deviation of three tested experiments. A All ΔCt(Tween 20) except ΔCt(0.5% Tween 20) have decreased values than ΔCt(control). High concentrations of Tween 20 improve non-specific amplification. B All concentrations of Ct(Tween 20, positive) have a decreased value than Ct(control, positive). Tween 20 also improves reactivity

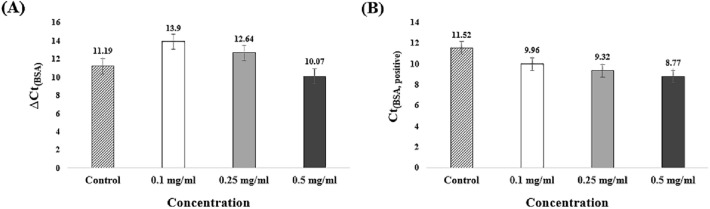

BSA

ΔCt value was calculated to analyze the non-specific amplification according to the concentration (Fig. 6(A)). The ΔCt value decreases with increasing concentration of BSA. That is, non-specific amplification is observed to be accelerated. ΔCt(0.1 mg/ml BSA) and ΔCt(0.25 mg/ml BSA) have increased values than ΔCt(control). Ct(0.1 mg/ml BSA, negative) was measured to be 23.86, and no significant effect was observed (Fig. S5). In addition, Ct(0.25 mg/ml BSA, negative) was obtained an increased value than Ct(control, negative). Ct(0.5 mg/ml BSA, negative) was observed decreased value than Ct(control). Non-specific amplification was accelerated to be 18.84. The Ct value decreases with increasing concentration of BSA (Fig. 6(B)). BSA contributes to stabilizing the activity of polymerase. This improves the amplification efficiency [41]. But, BSA causes DNA or RNA mismatches during nucleic acid amplification similar to Tween 20. Thus, non-specific amplification accelerated at all concentration conditions. BSA cannot be considered an appropriate additive by accelerating the overall reaction and non-specific amplification.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of ΔCt and Ct(BSA, positive) according to BSA concentration. Mean Ct and standard deviation of three tested experiments. A ΔCt(0.1 mg/ml BSA) and ΔCt(0.25 mg/ml BSA) have increased values than ΔCt(control). However, high concentrations of BSA decreased the ΔCt value. B The value of Ct(BSA, positive) decreased with increasing BSA concentration

Conclusion

Non-specific amplification is observed due to technical limitations of LAMP. To solve this problem, five additives were treated in the experiment and TMAC was presented as a promising additive. The inhibitory effect of non-specific amplification showed a concentration-dependent for TMAC. Non-specific amplification was dramatically suppressed with an increasing concentration of TMAC. Surprisingly, non-specific amplification was eliminated in 60 mM TMAC. TMAC is decreased slightly reactivity with a high concentration. However, positive sample was detected within 20 min under all concentrations. In conclusion, TMAC can be used by modifying the concentration according to the purpose. For the purpose of rapid detection in a short time, it is recommended to treat a low concentration of TMAC. In contrast, a high concentration of TMAC is recommended to completely eliminate non-specific amplification in studies or detection requiring high specificity.

Consequently, we report a novel alternative that can suppress non-specific amplification without primer redesign and probe design in LAMP. TMAC is expected to have the potential to be flexibly applied in various fields through the trade-off between detection time and specificity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Gachon University research fund of 2020(GCU-202008480009) and Research Investment for Global Health Technology Fund (RIGHT Fund) (RF-TAA-2020-D02).

Author contributions

MinJu Jang: conceptualization, methodology, validation, form analysis, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing original draft. Sanghyo Kim: Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yuce M, Kurt H, Mokkapati VRSS, Budak H. Employment of nanomaterials in polymerase chain reaction: insight into the impacts and putative operating mechanisms of nano-additives in PCR. RSC Adv. 2014;4:36800–36814. doi: 10.1039/C4RA06144F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mühl H, Kochem A-J, Disqué C, Sakka SG. Activity and DNA contamination of commercial polymerase chain reaction reagents for the universal 16S rDNA real-time polymerase chain reaction detection of bacterial pathogens in blood. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010;66:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delidow BC, Lynch JP, Peluso JJ, White BA. PCR Protocols. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1993. Polymerase Chain Reaction: Basic Protocols; pp. 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erlich HA. Polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Immunol. 1989;9:11. doi: 10.1007/BF00918012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Notomi T, Mori Y, Tomita N, Kanda H. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): principle, features, and future prospects. J Microbiol. 2015;53:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12275-015-4656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jawla J, Kumar RR, Mendiratta SK, Agarwal RK, Singh P, Saxena V, Kumari S, Boby N, Kumar D, Rana P. On-site paper-based loop-mediated isothermal amplification coupled lateral flow assay for pig tissue identification targeting mitochondrial CO I gene. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021;102:104036. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2021.104036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt J, Berghaus S, Blessing F, Wenzel F, Herbeck H, Blessing J, Schierack P, Rödiger S, Roggenbuck D. A semi-automated, isolation-free, high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase (RT) loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) test. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21385. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00827-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagamine K, Hase T, Notomi T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2002;16:223–229. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2002.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:63e–663. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park G-S, Ku K, Baek S-H, Kim S-J, Kim SI, Kim B-T, Maeng J-S. Development of reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays targeting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) J. Mol. Diagn. 2020;22:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JW, Nguyen VD, Seo TS. Paper-based molecular diagnostics for the amplification and detection of pathogenic bacteria from human whole blood and milk without a sample preparation step. BioChip J. 2019;13:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s13206-019-3310-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JH, Kang M, Park E, Chung DR, Kim J, Hwang ES. A simple and multiplex loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for rapid detection of SARS-CoV. BioChip J. 2019;13:341–351. doi: 10.1007/s13206-019-3404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choopara I, Suea-Ngam A, Teethaisong Y, Howes PD, Schmelcher M, Leelahavanichkul A, Thunyaharn S, Wongsawaeng D, deMello AJ, Dean D, Somboonna N. Fluorometric paper-based, loop-mediated isothermal amplification devices for quantitative point-of-care detection of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ACS Sens. 2021;6:742–751. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.0c01405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu W, Li Q, Cui X, Cao M, Xiong X, Wang L, Xiong X. Real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) using self-quenching fluorogenic probes: the application in Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) authentication. Food Anal. Methods. 2022;15:658–665. doi: 10.1007/s12161-021-02159-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W, Huang S, Liu N, Dong D, Yang Z, Tang Y, Ma W, He X, Ao D, Xu Y, Zou D, Huang L. Establishment of an accurate and fast detection method using molecular beacons in loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40125. doi: 10.1038/srep40125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou P-H, Lin Y-C, Teng P-H, Chen C-L, Lee P-Y. Real-time target-specific detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification for white spot syndrome virus using fluorescence energy transfer-based probes. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;173:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuboki N, Inoue N, Sakurai T, Di Cello F, Grab DJ, Suzuki H, Sugimoto C, Igarashi I. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for detection of african trypanosomes. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5517–5524. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5517-5524.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Özay B, McCalla SE. A review of reaction enhancement strategies for isothermal nucleic acid amplification reactions. Sens Actuators Rep. 2021;3:100033. doi: 10.1016/j.snr.2021.100033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali MM, Li F, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Kang D-K, Ankrum JA, Le XC, Zhao W. Rolling circle amplification: a versatile tool for chemical biology, materials science and medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:3324. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60439j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanaka ES, Tortajada-Genaro LA, Pastor N, Maquieira Á. Polymorphism genotyping based on loop-mediated isothermal amplification and smartphone detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018;109:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong F, Outhred AC, Iredell JR, Verweij JJ, Chen SC-A, James G, Lee R, Watts MR, Ginn AN, Sultana Y. A loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for strongyloides stercoralis in stool that uses a visual detection method with SYTO-82 fluorescent dye. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014;90:306–311. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang D-G, Brewster J, Paul M, Tomasula P. Two methods for increased specificity and sensitivity in loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Molecules. 2015;20:6048–6059. doi: 10.3390/molecules20046048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardinge P, Murray JAH. Reduced false positives and improved reporting of loop-mediated isothermal amplification using quenched fluorescent primers. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7400. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43817-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tani H, Teramura T, Adachi K, Tsuneda S, Kurata S, Nakamura K, Kanagawa T, Noda N. Technique for quantitative detection of specific dna sequences using alternately binding quenching probe competitive assay combined with loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:5608–5613. doi: 10.1021/ac070041e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khumwan P, Pengpanich S, Kampeera J, Kamsong W, Karuwan C, Sappat A, Srilohasin P, Chaiprasert A, Tuantranont A, Kiatpathomchai W. Identification of S315T mutation in katG gene using probe-free exclusive mismatch primers for a rapid diagnosis of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis by real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Microchem. J. 2022;175:107108. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2021.107108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahbazi E, Mollasalehi H, Minai-Tehrani D. Development and evaluation of an improved quantitative loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of Morganella morganii. Talanta. 2019;191:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenz TC. Polymerase chain reaction: basic protocol plus troubleshooting and optimization strategies. JoVE. 2012;2012:3998. doi: 10.3791/3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Ren G, Buss J, Barry AJ, Patton GC, Tanner NA. Enhancing colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification speed and sensitivity with guanidine chloride. Biotechniques. 2020;69:178–185. doi: 10.2144/btn-2020-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekikawa T, Kawasaki Y, Katayama Y, Iwahori K. Suppression of Bst DNA polymerase inhibition by nonionic surfactants and its application for cryptosporidium parvum DNA detection. Japanese J. Wat. Treat. Biol. 2008;44:203–208. doi: 10.2521/jswtb.44.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghaith DM, Abu Ghazaleh R. Carboxamide and N-alkylcarboxamide additives can greatly reduce non specific amplification in loop-mediated isothermal amplification for foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) using Bst 3.0 polymerase. J Virol Methods. 2021;298:114284. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yong D. Laboratory diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus. Korean J Healthc Assoc Infect Control Prev. 2020;25:63–65. doi: 10.14192/kjicp.2020.25.1.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung J, Bong J-H, Kim H-R, Park J-H, Lee CK, Kang M-J, Kim HO, Pyun J-C. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein antibodies derived from pig serum with a controlled specificity. BioChip J. 2021;15:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s13206-021-00019-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao, X., Huang, X., Zhou, Z., Lin, X.: An improvement of the 2ˆ(–delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. 13 (2014) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Rabaan AA, Tirupathi R, Sule AA, Aldali J, Mutair AA, Alhumaid S, Muzaheed, Gupta N, Koritala T, Adhikari R, Bilal M, Dhawan M, Tiwari R, Mitra S, Emran TB, Dhama K. Viral dynamics and real-time RT-PCR Ct values correlation with disease severity in COVID-19. Diagnostics. 2021;11:1091. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11061091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krajden M, Ziermann R, Khan A, Mak A, Leung K, Hendricks D, Comanor L. Qualitative detection of hepatitis C virus RNA: comparison of analytical sensitivity, clinical performance, and workflow of the Cobas Amplicor HCV Test Version 20 and the HCV RNA transcription-mediated amplification qualitative assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2903–2907. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2903-2907.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pum J. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. A practical guide to validation and verification of analytical methods in the clinical laboratory; pp. 215–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melchior WB, Hippel PHV. Alteration of the relative stability of dA dT and dG dC base pairs in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1973;70:298–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakrabarti R. The enhancement of PCR amplification by low molecular weight amides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2377–2381. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao X, Sun B, Guan Y. Pullulan reduces the non-specific amplification of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) Anal Bioanal Chem. 2019;411:1211–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-1552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao Z-X, Cao H-M, Luan X-H, Zhao J-L, Wei D-Z, Xiao J-H. Effects of additives on efficiency and specificity of ligase detection reaction. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;35:129–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02686107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farell EM, Alexandre G. Bovine serum albumin further enhances the effects of organic solvents on increased yield of polymerase chain reaction of GC-rich templates. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:257. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.