Abstract

Purpose:

Sexual assault care provided by sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) is associated with improved health and prosecutorial outcomes. Upon completion of SANE training, nurses can demonstrate their experience and expertise by obtaining SANE certification. Availability of nurses with SANE training or certification is often limited in rural areas, and no studies of rural certified SANEs exist. The purpose of this study is to describe rural SANE availability.

Methods:

We analyze both county-level and hospital-level data to comprehensively examine SANE availability. We first describe the geographic distribution of certified SANEs across rural and nonrural (ie, urban or suburban) Pennsylvania counties. We then analyze hospital-level data from semistructured interviews with rural hospital emergency department administrators using qualitative content analysis.

Findings:

We identified 49 certified SANEs across Pennsylvania, with 24.5% (n = 12) located in 8 (16.7%) of Pennsylvania’s 48 rural counties. The remaining 37 certified SANEs (75.5%) were located in 13 (68.4%) of Pennsylvania’s 19 nonrural counties. Interview data were collected from 63.9% of all eligible rural Pennsylvania hospitals (n = 63) and show that 72.5% (n = 29) have SANEs. Of these, 20.7% (n = 6) have any certified SANE availability. A minority of hospitals (42.5%; n = 17) have continuous SANE coverage.

Conclusions:

Very few SANEs in rural Pennsylvania have certification, suggesting barriers to certification may exist for rural SANEs. Though a majority of hospitals have SANEs, availability of SANEs was limited by inconsistent coverage. A lack of certified SANEs and inconsistent SANE coverage may place rural sexual assault victims at risk of receiving lower quality sexual assault care.

Keywords: access to care, rural, sexual assault, sexual assault nurse examiners

In the United States, more than 400,000 adults and adolescents (12 years or older) experience sexual assault each year.1 Following a sexual assault, victims presenting for medical care require an array of services that can include attention to physical trauma, history and physical exam with forensic evidence collection, mental health support, sexually transmitted illness prophylaxis, and emergency contraception.2 Such care requires specialized clinical knowledge not only to provide high-quality health care but also to avoid a “secondary victimization” occurring during the medical encounter.3 Secondary victimization, a term referring to the devastating effects of victim-shaming and victim-blaming, can exacerbate or worsen health outcomes and lead to negative sequelae such as pain, emotional harm, or deterrence from help-seeking for health or judicial support.3,4

One model to provide this specialized, comprehensive care to adult and adolescent victims of sexual assault is the sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) model.5,6 SANEs are registered nurses with additional training in evaluating the unique health care needs and provision of specialized health care services to victims of sexual assault.5–7 In the SANE model, registered nurses can work full time in a given department—typically the emergency department (ED)—yet also be available to care for sexual assault victims on an as-needed basis.

As nurses are already embedded within hospitals, the SANE model is an appealing and frequently used approach that more easily allows hospitals to provide sexual assault care services.5–7 The trauma-informed, person-centered approach used by SANEs, which focuses on ensuring victims are fully informed of their options and restoring choice and control throughout the examination, has a positive impact on the psychological well-being of sexual assault survivors by allowing them to feel safe, supported, respected, believed, and well-cared for.4,8 SANEs have also demonstrated an impact on the quality of the medical treatments received by victims of sexual assault by increasing the rate of provision of sexually transmitted illness prophylaxis and emergency contraception.6,7

In addition to the positive impacts of SANE-led care on psychological and health outcomes, research also suggests that SANEs may positively impact prosecutorial outcomes pertaining to sexual assault perpetrators. For instance, SANEs collect more thorough evidence through the use of specialized medical equipment (eg, colposcopes).4,9–11 More thorough, higher quality forensic evidence collected by SANEs is associated with favorable prosecutorial outcomes such as plea bargains.9,10,12 Additionally, SANEs’ testimony in court and role in facilitating improved cross-agency interactions among medical and legal entities may also contribute to improved prosecutorial outcomes.9,11,13 Recognizing the value that SANEs provide to victims of sexual assault, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) provides resources for practice guidelines and SANE program evaluation to increase their availability and effectiveness.5,14

A recent report commissioned by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that challenges related to the availability of SANEs persist despite finding positive associations between SANE-led care, forensic evidence collection, and physical and mental health outcomes.15 More specifically, the report cited limited availability of SANE training, lack of support from hospitals or law enforcement for developing and maintaining SANE programs, and low SANE retention rates due to the demanding nature of the work.15 SANE training is not only limited, but SANE programs can vary substantially in terms of training and ongoing education requirements.7,15

The DOJ’s Office on Violence Against Women, in conjunction with the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN), has provided guidelines for SANE training and clinical practice, while organizations, including the IAFN, provide education and training for nurses interested in becoming SANEs.16 Nurses with SANE training may also seek IAFN certification after meeting rigorous education and clinical practicum hours and passing a written certification exam. IAFN certification is the only certification recognized by the American Nurses Credentialing Center—a subsidiary of the American Nurses Association—that administers certification exams for both registered and advanced practice nurses.17

Aside from DOJ training guidelines and an optional, national SANE certification through the IAFN, there is no federal regulatory oversight regarding who can provide adult and adolescent sexual assault care and, relatedly, the quality of sexual assault care being provided. As a result, whether IAFN or any other training or certification is required for clinicians to be able to provide adult and adolescent sexual assault care varies by state.5,15 For instance, several states including Maryland and Massachusetts require SANEs to meet specific criteria and obtain certification through the state’s Board of Nursing to be able to provide sexual assault care,18,19 while others such as Pennsylvania require no such certification.

In the absence of state requirements, facilities (ie, hospitals or health care systems) determine who will provide sexual assault care and make independent determinations of training and certification requirements, if any. Facilities may pay for a select number of nurses to take an IAFN or other 40-hour training program, develop sexual assault care training programs within their facility, or may allow ED providers without specialty sexual assault care training to conduct examinations.6,15 The latter is particularly troubling considering the majority of medical and nursing school programs do not provide training in sexual assault care provision.20,21 In states without training or certification requirements for nurses providing sexual assault care, there is potential for substantial differences in hospital-based SANE programs due to lack of quality oversight.

In Pennsylvania, the state’s department of health provides suggested forensic documentation forms and evidence collection kits for sexual assault but does not provide any quality oversight related to required training for providers of adult and adolescent sexual assault care.22 Pennsylvania does, however, mandate that all hospitals with emergency services provide care to sexual assault victims, and hospitals can be fined for failing to provide this service.23

In addition to penalties for failing to provide sexual assault care, payment structures for sexual assault care provision are established at the state level. In Pennsylvania, hospitals are compensated for providing sexual assault services with federal Victims of Crime Act funds allocated to a state-level agency, Victims Compensation Assistance Program (VCAP); hospitals submit a claim to VCAP for reimbursement after providing sexual assault care.24 However, the maximum a hospital can bill for costs associated with completion of a forensic rape examination is $1,000.24 The costs to hospitals for providing victims with one-on-one nursing care and an ED bed for several hours, needed bloodwork, prescriptions, imaging, and other aspects of care often well exceed $1,000.25 Pennsylvania law permits hospitals to ask for victims’ permission to bill their private insurance for additional costs but prohibits any billing that would lead to charges being incurred by the victim (eg, copays, deductible payments).24

Low compensation rates may create little financial incentive to build and retain sexual assault care expertise, particularly in rural areas that may also lack other resources for sexual assault victims.26 Rural hospitals often experience financial and workforce constraints that can impact the quality of services they are able to provide.27 Prior research has demonstrated this may also be true for sexual assault care.28

In the absence of federal or state training and certification standards, facility-based requirements for who provides sexual assault care may lead to variation in the quality of care and forensic evidence collection that victims of sexual assault receive, particularly in rural communities.28,29 To determine if such variability in quality may be present in rural areas, we examined the geographic availability of SANEs in rural Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania’s lack of state-level SANE or sexual assault care provision requirements and its largely rural geography may contribute to differences in SANE availability for adult and adolescent sexual assault victims.

While previous studies have examined the extent to which specific elements of sexual assault care are provided by hospitals across a state,30 no studies have examined how availability of trained sexual assault providers such as SANEs may differ across a state’s rural areas. Though lack of availability of a health care service within a geographical area (ie, geographic availability) is not the only barrier that may exist for individuals seeking a particular type of health care service, lack of geographic availability can lead to disparities in access to care.31 Our examination of geographic availability of SANEs in rural Pennsylvania is an initial step in understanding whether access to sexual assault care services may be disparate for rural communities and whether additional federal- or state-level policies may be needed to ensure that all sexual assault victims receive quality care.

Data and Methods

Pennsylvania does not require SANE certification through the Board of Nursing, nor does it set minimum provider qualifications or require hospitals to report information regarding their sexual assault care providers. As a result, there is no statewide data available to understand who is providing sexual assault care in rural communities or to determine their level of training. We therefore examined SANE availability using a multipronged approach that included an analysis of IAFN-certified SANEs in Pennsylvania and rural hospital-level SANE availability.

First, we examined the presence of SANEs with publicly available IAFN certification across the entire state to determine whether IAFN-certified SANEs are present in rural communities and whether differences exist between the state’s rural and nonrural (eg, urban, suburban) counties. We then specifically focused on rural availability of nurses with any SANE training (without certification) by analyzing hospital-level data collected during interviews with rural Pennsylvania hospital administrators about how sexual assault care is provided to victims presenting to their EDs.

Data

A list of all SANEs with IAFN certification in Pennsylvania was obtained from the IAFN website and used to create a county-level database for the analysis of IAFN-certified SANE geographic distribution.32 For the hospital-level data, we conducted semistructured telephone interviews with rural Pennsylvania hospital ED administrators or nurses. Interviews were conducted between June and August of 2018 as part of a larger project aimed at improving sexual assault care in rural Pennsylvania using telehealth to pair less experienced nurses with expert, certified SANEs.33

All hospitals in rural Pennsylvania counties that provided emergency services were eligible for inclusion. Interviews of ED administrators or any available ED staff with knowledge of how sexual assault care was provided (eg, ED directors or managers, SANE team coordinators, ED nurse managers, ED nursing clinical coordinators, or ED charge nurses) were conducted by the first author. Annotated responses to interview questions were entered into a database for analysis. Additional hospital-level information, including the size of the hospital (number of beds) and federal Critical Access Hospital designation were obtained from individual hospital websites, the Hospital Association of Pennsylvania,34 and the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health.35

Measures

Pennsylvania county rurality was determined according to the Center for Rural Pennsylvania’s rural county definition.36 This definition, which is based on population density per square mile, was chosen due to its frequent use by Pennsylvania’s state legislature when considering rural issues and policymaking.37 According to this definition, 48 (71.6%) of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties are rural.

Availability of SANEs was assessed using a brief, semistructured interview developed for this study that focused on 2 main areas: SANE presence and SANE coverage. First, SANE presence measures whether nurses with SANE training (with or without certification) were primarily leading the care for victims of sexual assault in the hospital’s ED. To measure SANE presence, we asked participants whether SANEs cared for victims of sexual assault or, if not, who provided the sexual assault care in their ED. If SANEs were present, we also asked whether any had IAFN certification.

In addition to SANE presence, it was also important to assess SANE coverage as a measure of SANE availability. Our own experience and prior research has suggested hospitals often have nurses with SANE training or certification on staff, but whether a patient actually receives care from a SANE depends on whether there is a call system or whether the SANE was available when the sexual assault victim presented for care.33,38 That is, the victim would only receive care from a SANE if the SANE happened to be working at the time the sexual assault victim presented for care or if the SANE could come in on their day off.

To measure SANE coverage within each hospital, we asked participants to describe their process for obtaining a SANE when a sexual assault victim presented to the ED. Specifically, we asked if a scheduling system, such as a call or other system, existed so that a SANE could always be available should a victim of sexual assault present to the ED. If SANEs were on staff but there was no scheduling system to ensure coverage, we then asked who would provide sexual assault services if the hospital’s SANEs were not working or unable to come in on their day off when a sexual assault victim presented.

Analysis

We first provide descriptive information for the distribution of IAFN-certified SANEs across rural and nonrural Pennsylvania counties (Table 1). We used ArcMAP (version 10.7.1, Esri, Redlands, CA) to provide a visual representation of IAFN-certified SANE distribution across rural and nonrural Pennsylvania counties.39 Responses to interview questions were analyzed using a qualitative, directed content analysis approach40 in order to create categories of SANE availability with respect to SANE presence and SANE coverage for all hospitals in the sample. This qualitative approach, as opposed to a survey, allowed for open-ended and thus more detailed explanations of whether and how hospitals provided access to SANEs.40

Table 1.

Distribution of lAFN-Certified SANEs in Pennsylvania, Frequency (%)

| IAFN-Certified SANEs (n = 49) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rural PA IAFN-certified SANEs | 12 | (24.5) |

| Nonrural PA IAFN-certified SANEs | 37 | (75.5) |

| PA counties (n = 67) with IAFN-certified SANEs | 21 | (31.3) |

| Rural counties (n = 48) with IAFN-certified SANE(s) | 8 | (16.7) |

| Nonrural counties (n = 19) with IAFN-certified SANEs | 13 | (68.4) |

PA = Pennsylvania; IAFN = International Association of Forensic Nurses; SANE = sexual assault nurse examiner.

Results

Geographic Distribution of IAFN-Certified SANEs in Pennsylvania

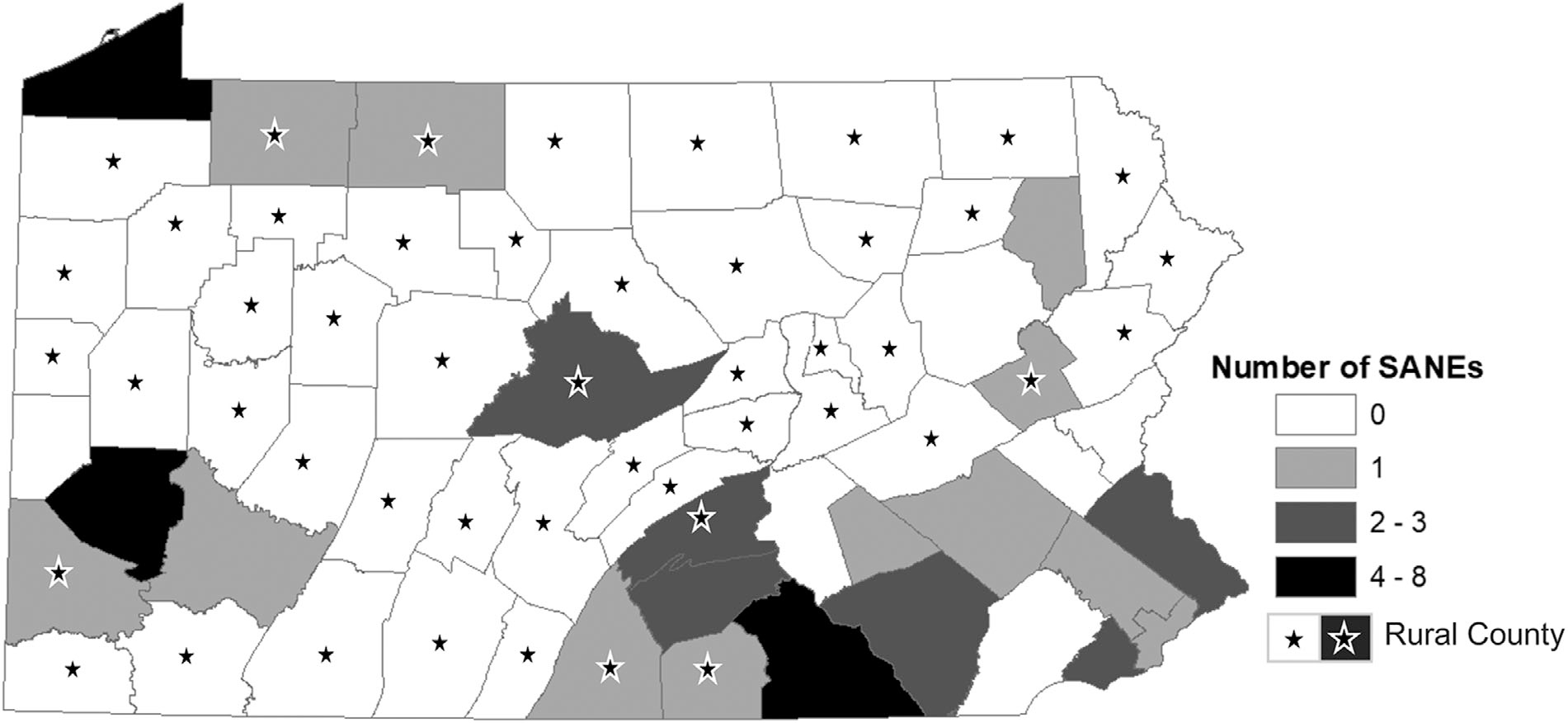

Table 1 and Figure 1 display the results of the geographic distribution of IAFN-certified SANEs in Pennsylvania. Our analysis found 49 IAFN-certified SANEs in Pennsylvania, 12 (24.5%) of whom live in rural counties. These 12 IAFN-certified SANEs live in 8 distinct rural counties, or 16.7% of all rural counties. The remaining 40 rural counties, or 83.3% of rural counties, do not have any IAFN-certified SANEs. The 37 IAFN-certified SANEs practicing in Pennsylvania’s nonrural counties were distributed across 13 counties, or 68.4% of Pennsylvania’s 19 nonrural counties.

Figure 1.

Distribution of IAFN-Certified SANEs in Pennsylvania

SANE-Led Sexual Assault Care in Rural Pennsylvania Hospitals

We identified 63 hospitals offering emergency services in rural Pennsylvania counties and obtained information from 40 (63.5%) hospitals. Hospitals were called a minimum of 3 times and voicemails with the researchers’ contact information were left with ED administrators if there was no answer. We asked to interview 1 person from each hospital (n = 40) with knowledge of the sexual assault protocols and/or SANE program. The majority of interview participants were ED directors or managers (n = 24). However, in several instances ED directors or managers were either unavailable or felt that other ED staff may be better able to answer interview questions. As a result, information for 16 of the hospitals in our sample were instead collected from ED clinical coordinators (n = 3), ED charge nurses or SANEs (n = 7), or SANE coordinators (n = 6). Interviews lasted no longer than 30 minutes. Descriptive information for hospitals is included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hospital Sample Characteristics (n = 40), Frequency

| Number of beds* | |

|

| |

| 23–50 beds | 3 |

| 50–100 beds | 14 |

| 101–150 beds | 6 |

| 151–200 beds | 4 |

| 201–250 beds | 5 |

| 251–300 beds | 4 |

| 301–350 beds | 2 |

| >350 | 2 |

| Critical access hospital | 4 |

|

| |

| Health system affiliation | |

|

| |

| Member of health system with multiple hospitals | 33 |

| Main hospital within health system | 7 |

| None** | 7 |

Mean number of beds: 153.6; range of number of beds 23–552.

Independent hospital/health system.

The majority of participating hospitals had less than 150 beds. Additionally, 4 were federally designated Critical Access Hospitals, which are hospitals located in a rural area at least 35 miles from any other hospital that provides emergency services, that have no more than 25 inpatient beds, and that have an average length of inpatient stay less than 96 hours.41 Most hospitals (n = 33; 82.5%) were affiliated with a larger health system, while the remaining 7 were hospitals independent of a broader health system (ie, independent hospitals). Additionally, 7 (21.2%) of the hospitals within health systems were the “main” or largest hospital in their health system while the remaining 26 (78.8%) were smaller, affiliated hospitals.

SANE Presence

Table 3 presents the results for SANE presence and coverage. The majority (72.5%; n = 29) of hospitals reported having nurses with SANE training, while 11 hospitals (27.5%) reported having no SANEs on their staff. Only 3 hospitals (7.5%) reported having 1 or more IAFN-certified nurses on their staff, and 3 additional hospitals with SANEs also had IAFN-certified SANEs available via telehealth (though these nurses were not part of the hospital’s paid staff). When examining SANE presence by hospital size, the proportion of hospitals with any SANEs ranged from 60% among hospitals with 101–200 beds to 100% among hospitals with 201–300 beds. Hospitals with 101–200 beds did not have any IAFN-certified SANEs, whereas at least 1 hospital with <100 beds and >200 beds reported having an IAFN-certified SANE.

Table 3.

Rural Pennsylvania Hospital SANE Availability, Frequency (%)

| All Hospitals (n = 40) | <100 Beds (n = 17) | 101–200 Beds (n = 10) | 201–300 Beds (n = 9) | >300 Beds (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SANE Presence | |||||

| Hospitals with any nurses with SANE training | 29 (72.5) | 11 (64.7) | 5 (50.0) | 9 (100.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| SANEs in-house | 26 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 3 |

| SANEs available to come from affiliated hospital | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| SANEs available to come from advocacy center | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hospitals with any SANEs with IAFN certification (total) | 6 (15.0) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (25.0) |

| IAFN-certified SANEs in-house | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| IAFN-certified SANEs available via Telehealth* | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SANE Coverage | |||||

| 24/7 SANE coverage (total) | 17 (42.5) | 5 (29.4) | 1 (10.0) | 7 (77.8) | 3 (75.0) |

| Formal, in-house call system | 14 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| SANEs from larger in-network facility on call | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SANEs from advocacy/rape crisis center on call | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Partial SANE coverage** | 12 (30.0) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| No SANE coverage | 11 (27.5) | 6 (35.3) | 5 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| No SANEs; RNs without SANE training, | |||||

| Physicians, NPs, or PAs provide majority of care | 10 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Transfer to larger in-network facility | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

SANE = sexual assault nurse examiner; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant; IAFN = International Association of Forensic Nurses.

Via telehealth, not part of paid hospital staff.

SANE only available if already working or can come in on day off.

SANE Coverage

The majority of hospitals reported having either partial SANE coverage (ie, SANE is available if already working that day or can come in on day off) or not having any nurses with SANE training on staff: 30% and 27.5%, respectively. Among the 17 hospitals with 24 hours a day, 7 days a week SANE coverage, 1 reported SANEs were on-call at the larger facility in their health system and could come to their hospital to provide care, while another 2 reported having SANE coverage through a local victim advocacy and rape crisis center. Three hospitals with an on-call system included an on-site SANE providing care to victims of sexual assault while a remote IAFN-certified SANE assisted virtually. Of the hospitals without SANEs, 3 reported transferring victims of sexual assault to the larger hospital within their health system for care. The proportion of hospitals with 24/7 SANE coverage ranged from 10% (hospitals with 101–200 beds) to 77.8% (hospitals with 201–300 beds). The majority (90%) of hospitals with 101–200 beds had partial or no SANE coverage, while the smallest hospitals in the sample (<100 beds) were nearly equally distributed across 24/7 SANE coverage (29.4%), partial SANE coverage (35.3%), and no SANE coverage (35.3%).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that availability of SANEs across rural Pennsylvania varies both in terms of where IAFN-certified SANEs practice as well as whether and how rural hospitals provide SANE-led care. Our analysis of IAFN SANE certification data demonstrated a concentration of IAFN-certified SANEs in nonrural Pennsylvania counties. These results largely agree with findings from our interviews with individual hospitals—out of 40 hospitals included in our analysis, very few (n = 3, 7.5%) endorsed having any IAFN-certified SANEs on their staff.

The absence of certified SANEs in the majority of rural Pennsylvania counties could be indicative of barriers to achieving these practice-related certification requirements for rural SANEs. One potential barrier to certification could be difficulty obtaining the supervised practice hours required for certification eligibility. Specifically, nurses must complete a SANE clinical preceptorship and have 300 hours of “SANE-related practice” that can involve any combination of providing direct care to a sexual assault victim, taking on-call shifts to care for victims of sexual assault, teaching or precepting SANEs, providing SANE consultations, and engaging in peer review of SANE cases.42 Relatedly, there are fewer available SANEs in rural areas that can serve as clinical practicum supervisors and mentors for rural nurses interested in becoming certified SANEs.

Low volume of sexual assault cases presenting to rural hospitals is another potential barrier for SANEs seeking certification. As the US GAO report on SANE availability suggested, rural areas do not have the volume of sexual assault cases to allow nurses to attain and retain proficiency in the provision of sexual assault care.15 Though we did not specifically investigate the volume of sexual assault victims presenting to each rural hospital in our sample, several participants stated they rarely had to care for sexual assault victims, often seeing fewer than 10 cases per year.

While low volume of sexual assault cases (ie, demand) may limit the ability of rural SANEs to gain experience and expertise, it is important to note that sexual assault cases as a rate per 100,000 persons is not lower in rural areas and some evidence suggests it may even be higher.43,44 For instance, in each of the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for the years 2016, 2017, and 2018, the rate of rape reports per 100,000 persons was higher in nonmetropolitan (ie, rural) counties. More specifically, rape reports per 100,000 persons in rural counties was 39.1, 39.2, and 40.7 for years 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively and 32.3, 32.5, and 34.4, respectively, for metropolitan (ie, nonrural) counties.45–47 Additionally, an empirical study of both FBI rape reporting statistics and data collected from Pennsylvania rape crisis centers also found the rate of sexual assault to be higher in rural counties.43

Another potential barrier to SANE training and certification could be related to the costs associated with IAFN certification. For example, the fee for the IAFN certification exam ranges from $275 to $425, with renewal fees ranging from $175 to $575 required every 3 years.42 Additional costs for travel to training and testing sites are also likely for rural nurses as these sites are often in nonrural areas. If rural hospitals—often under financial constraints—see very few sexual assault victims presenting to their EDs each year and are not required to meet a minimum quality standard, there may not be an incentive for them to assist rural nurses with these costs. Additionally, personal financial investment in SANE certification and the completion of SANE-related clinical hours may not be a priority for a full-time ED nurse in a rural hospital who only occasionally engages in the provision of sexual assault care.

Future work should investigate barriers to SANE training and certification, particularly for rural nurses. Additional research is also needed to better understand how low volume of sexual assault cases in rural EDs impacts the ability of rural SANEs to attain and retain adequate clinical expertise and how this affects the quality of care rural sexual assault victims receive. Future studies examining SANE availability would also benefit from incorporating county-specific estimates of sexual assault prevalence to identify areas with the greatest need for sexual assault care. Additional research is also needed to better understand whether and how compensation programs and/or low volume of sexual assault cases affect hospital decision-making regarding investment in sexual assault care services such as SANE programs. As we noted earlier, issues related to rates of sexual assault per 100,000 persons in rural areas raise concerns that rural areas have a need for SANEs, yet lower absolute number of cases and compensation issues may present rural hospitals with challenging decisions to make about how much to invest into sexual assault care capacity.

The results of our hospital-level SANE availability analysis also demonstrated variability not only in the availability of SANEs but also, among hospitals with SANE availability, the ways in which they provide SANE-led care. Our findings confirmed the previous practice experiences of this study’s coauthors while working with SANEs in rural areas—many hospitals have nurses with SANE training on staff, but they are not always available due to the absence of a call system to ensure coverage. The existence of partial SANE coverage in rural Pennsylvania hospitals is also consistent with findings of a national survey conducted by Patel and colleagues in which only 44% of hospitals had trained sexual assault care providers available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, while 19.2% of hospitals had a trained sexual assault care provider on-site sometimes and 33.3% never had a trained sexual assault care provider on-site.38 Unfortunately, the consequence of partial SANE coverage is that the quality of care victims of sexual assault receive when presenting to the ED may depend on the day of the week or time of day they present for care.

Our findings also provide insight into the role that health system resources may play in the availability of SANEs in rural counties. While the majority (82.5%) of hospitals in our sample were part of a larger health system, very few reported having some type of agreement or coordination with the main hospital in their health system that allowed for victims of sexual assault to access SANE care within their facility. In fact, only 1 hospital stated that SANEs on-call from the main hospital were able to come to their facility to care for sexual assault victims, while 3 stated they would transfer these cases to the main hospital. Though transfer to another facility may help ensure victims receive quality sexual assault care, such transfers may require unwanted travel from victims’ home communities and could deter them from seeking care. While no studies we are aware of examine the effect of transfer to another facility on whether victims of sexual assault decide to pursue medical care, a large majority of sexual assault victims are already hesitant to seek care, and any additional hurdles to receiving care such as long waits or transfers to other hospitals would likely deter some victims from seeking care.26

Limitations

Despite demonstrating a concentration of certified SANEs in nonrural counties as well as substantial variability in SANE-led care in rural Pennsylvania, this study has several limitations. First, we attempted to conduct interviews with hospital staff who have knowledge of how sexual assault care is provided in their hospital. While we expected most ED staff in nursing or other administrative roles would be familiar with the existence of on-call schedules, what (if any) training is required to provide sexual assault care in their facility, and whether specific staff were designated to provide sexual assault care, there is still the possibility of reporting error.

Second, the existence of Pennsylvania laws prohibiting hospitals from denying care to sexual assault victims may have caused interview participants to be less forthcoming about practices such as informally referring victims to other hospitals (ie, suggesting victims seek care elsewhere). We suspect, based on anecdotal experiences, that these practices may regularly occur; however, we were unable to confirm this empirically with our interviews and are unaware of other research into this specific issue.

Third, we only conducted interviews with participants in rural Pennsylvania hospitals. We therefore did not compare rural and nonrural county SANE availability beyond the initial examination of the geographic distribution of IAFN-certified SANEs. We also did not examine SANE availability beyond the state level. It may certainly be the case that there is also limited SANE availability in Pennsylvania’s nonrural counties, and our focus on Pennsylvania limits the generalizability of our findings. However, states’ approaches to regulating sexual assault care differ substantially and complicate state-to-state comparisons. Our findings nevertheless may provide some insight for other states that, like Pennsylvania, do not regulate provider qualifications for adult and adolescent sexual assault care. Additionally, future work should investigate how SANE availability may differ in nonrural areas and the potential drivers of limited SANE availability for nonrural areas.

The results of this study cannot be used to draw any conclusions about the actual quality of care that rural hospitals are providing to victims of sexual assault as we did not systematically investigate the type or quality of training, nor the amount of practical experience of the clinicians (SANEs, physicians, etc) providing sexual assault care within these hospitals. Our findings do, however, demonstrate that certified SANEs—those who have substantial time in the field and have demonstrated proficiency by exam—are largely not practicing in rural areas. This raises concerns that disparities in the quality of care received by victims of sexual assault may exist, as evidence from pediatric sexual assault care suggests that certification can enhance the quality of care through more accurate diagnosis of injury.48 However, evidence on the effect of certification on adult and adolescent sexual assault care is lacking. Our results justify further inquiries into the quality of care rural victims of sexual assault receive in the absence of certified SANE availability.

Finally, we were also unable to account for SANEs who may practice in a county other than where they reside (for instance, a neighboring county). While our analysis found 8 rural counties with at least 1 IAFN-certified SANE residing there, we could not determine whether these SANEs practiced in Pennsylvania’s rural or nonrural counties. The opposite may also be true—IAFN-certified SANEs in nonrural counties may be practicing in rural counties and we could not determine this with our data. We did attempt to account for some of this shortcoming by confirming whether an IAFN-certified SANE was residing within the county or adjacent counties of hospitals reporting they had IAFN-certified SANEs on their staff. We were able to confirm IAFN-certified SANEs resided in the counties of 2 of these 3 hospitals; however, the third hospital bordered New York state. As a result, we could not verify their report with our data as we did not include New York state data in our analysis.

Despite these limitations, we found that only 16.7% of rural Pennsylvania counties have an IAFN-certified SANE, while 68.4% of nonrural counties have an IAFN-certified SANE. When considering 46 of 67 total Pennsylvania counties, or 68.7%, do not have IAFN-certified SANEs, there is a clear need to better understand who is providing care to sexual assault victims in these counties and whether the quality of care is sufficient. We demonstrated that hospitals clearly differ in their individual SANE availability, both in terms of how many nurses have any SANE training and whether they are always available. Future studies investigating whether rural victims of sexual assault are receiving lower quality sexual assault care are critically needed, as our study has demonstrated a lack of IAFN-certified SANEs and variation in the availability of nurses with any SANE training across rural Pennsylvania hospitals.

Conclusions

SANE availability varies throughout rural Pennsylvania. Further research is needed to better understand how hospitals make decisions related to how they will provide sexual assault care and how ecological factors, such as hospital resources, the population size of the surrounding community, organizational culture, and state-level oversight may influence this decision-making. Creative solutions are likely needed to assist rural hospitals with provision of this important health care service. Additionally, state or federal oversight may be necessary to more uniformly prepare SANEs or other providers to deliver care to victims of sexual assault in order to avoid disparities not only in the quality of care received, but also in the negative outcomes that can follow experiencing poor sexual assault care such as secondary trauma or inadequate forensic evidence collection.

Acknowledgments:

The authors are grateful to Madisyn Barnes and Joselyn Neiderer for their contributions to data collection and manuscript editing.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) Award #: 2016-NE-BX-K001; National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Award # P50HD089922; and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002014. The funding sources were not involved in the study design and the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US DOJ or National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Rape Abuse & Incest National Network. Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics | RAINN. https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence. Published 2019. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick HS, Holmes MM, Kilpatrick DG, et al. Predictors of post-rape medical care in a national sample of women. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):214–219. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell R, Wasco SM, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Barnes HE. Preventing the “Second Rape.” J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(12):1239–1259. 10.1177/088626001016012002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell R The psychological impact of rape victims′experiences with the legal, medical, and mental health systems. Am Psychol. 2008;63(8):702–717. 10.1037/0003-066X.63.8.702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women. National Training Standards for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examiners. Washington, DC, US Dept of Justice; 2018. https://www.justice.gov/ovw/page/file/1090006/download. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciancone AC, Wilson C, Collette R, Gerson LW. Sexual assault nurse examiner programs in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(4):353–357. 10.1016/S0196-0644(00)70053-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell R, Townsend SM, Long SM, et al. Respondingto sexual assault victims′ medical and emotional needs: a national study of the services provided by SANE programs. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):384–398. 10.1002/nur.20137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ericksen J, Dudley C, McIntosh G, Ritch L, Shumay S, Simpson M. Clients’ experiences with a specialized sexual assault service. J Emerg Nurs. 2002;28(1):86–90. 10.1067/men.2002.121740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell R, Patterson D, Bybee D. Prosecution of adult sexual assault cases: a longitudinal analysis of the impact of a sexual assault nurse examiner program. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(2):223–244. 10.1177/1077801212440158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell R, Bybee D, Townsend SM, Shaw J, Karim N, Markowitz J. The impact of sexual assault nurse examiner programs on criminal justice case outcomes: a multisite replication study. Violence Against Women. 2014;20(5):607–625. 10.1177/1077801214536286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sievers V, Murphy S, Miller J. Sexual assault evidence collection more accurate when completed by sexual assault nurse examiners: Colorado’s experience. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29(6):511–514. 10.1016/j.jen.2003.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crandall C, Helitzer D. Impact Evaluation of a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Program. Albuquerque, NM; Albuquerque, New Mexico. 2003. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/203276.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell R, Patterson D, Lichty LF. The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2005;6(4):313–329. 10.1177/1524838005280328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evaluating Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Programs | National Institute of Justice. Available at https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/evaluating-sexual-assault-nurse-examiner-programs. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clowers N Sexual assault: information on the availability of forensic examiners. Justice Law Enforc Rep. 2018;2019:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women. A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations—Adults/Adolescents Second Edition, 2013). Washington, DC:. US Dept of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Nurses Credentialing Center | ANCC. https://www.nursingworld.org/ancc/. Accessed July 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maryland Board of Nursing. Forensic nurse examiner. Available at https://mbon.maryland.gov/Pages/forensicnurse-examiner.aspx. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 19.The 191st General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Title XVI, Chapter 111, Section 220. Available at https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXVI/Chapter111/Section220. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 20.Siegel M, Gonzalez EC, Wijesekera O, et al. On-the-go training: downloadable modules to train medical students to care for adult female sexual assault survivors. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13(1):mep_2374–8265.10656. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strunk JL. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of prenursing and nursing students about sexual assault. J Forensic Nurs. 2017;13(2):69–76. 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sexual Assault Evidence Collection. Available athttps://www.health.pa.gov/topics/programs/violence-prevention/Pages/Sexual-Assault-Evidence-Collection.aspx. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 23.Pennsylvania Bulletin. Sexual assault victim emergency services. Available at http://www.pacodeandbulletin.gov/Display/pabull?file=/secure/pabulletin/data/vol38/38-4/170.html. Published 2008. Accessed April 2, 2020.

- 24.Manual for Compensation Assistance, Victims Compensation Assistance Program. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency Office of Victims’ Services. Available at http://www.dave.pa.gov. Accessed November 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tennessee AM, Bradham TS, White BM, Simpson KN. The monetary cost of sexual assault to privately insured US women in 2013. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):983–988. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logan TK, Evans L, Stevenson E, Jordan CE. Barriers to services for rural and urban survivors of rape. Journal of interpersonal violence 2005;20(5):591–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moscovice I, Stensland J. Rural hospitals: trends, challenges, and a future research and policy analysis agenda. J Rural Health. 2002;18(5):197–210. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyamoto S, Dharmar M, Boyle C, et al. Impact of telemedicine on the quality of forensic sexual abuse examinations in rural communities. Child Abus Negl. 2014;38(9):1533–1539. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLeod KJ, Marcin JP, Boyle C, Miyamoto S, Dimand RJ, Rogers KK. Using telemedicine to improve the care delivered to sexually abused children in rural, underserved hospitals. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):223–228. 10.1542/peds.2007-1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel A, Panchal H, Piotrowski ZH, Patel D. Comprehensive medical care for victims of sexual assault: a survey of Illinois hospital emergency departments. Contraception. 2008;77(6):426–430. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Access to Health Services | Healthy People 2020. Available at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services. Accessed July 14, 2020.

- 32.Member Search—International Association of Forensic Nurses. Available at https://www.forensicnurses.org/search/. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 33.Miyamoto S, Thiede E, Dorn L, Perkins DF, Bittner C, Scanlon D. The Sexual Assault Forensic Examination Telehealth (SAFE-T) Center: a comprehensive, nurse-led telehealth model to address disparities in sexual assault care. J Rural Heal. 2020: 10.1111/jrh.12474. Published online June 8 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Interactive Map. Available at https://www.haponline.org/About-PA-Hospitals/Interactive-Map. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 35.Directory | Critical Access Hospitals | CAH | Rural Hospitals | Contact | Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health. Available at https://www.porh.psu.edu/hospital-and-health-system-initiatives/critical-access-hospitals/critical-access-hospitals-directory/. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rural Pennsylvania Counties—The Center for Rural PA. Available at https://www.rural.palegislature.us/demographics_rural_urban_counties.html. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 37.Mission Statement—The Center for Rural PA. Available at https://www.rural.palegislature.us/about_mission_statement.html. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 38.Patel A, Roston A, Tilmon S, et al. Assessing the extent of provision of comprehensive medical care management for female sexual assault patients in US hospital emergency departments. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;123(1):24–28. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ArcMap | Documentation. Available at https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Critical Access Hospital | Medicare Cost-based Reimbursement | Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health. Available at http://www.porh.psu.edu/hospital-and-health-system-initiatives/critical-access-hospitals/. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Exam Details—International Association of Forensic Nurses. Available at https://www.forensicnurses.org/page/ExamDetails#anchor_1477508752637. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 43.Ruback RB, Ménard KS. Rural-urban differences in sexual victimization and reporting. Crim Justice Behav. 2001;28(2):131–155. 10.1177/0093854801028002001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis SH. Sexual Assault in Rural Communities, 2003. Available at https://vawnet.org/material/sexual-assault-rural-communities. Accessed October 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45.FBI — Rape. Available at https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.−2018/topic-pages/rape. Accessed October 16, 2020.

- 46.FBI — Rape Available at https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.−2017/topic-pages/rape. Accessed October 16, 2020.

- 47.FBI — Rape Available at https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.−2016/topic-pages/rape. Accessed October 16, 2020.

- 48.Adams JA, Starling SP, Frasier LD, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in child sexual abuse medical evaluation: role of experience, training, and expert case review. Child Abus Negl. 2012;36(5):383–392. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]