Abstract

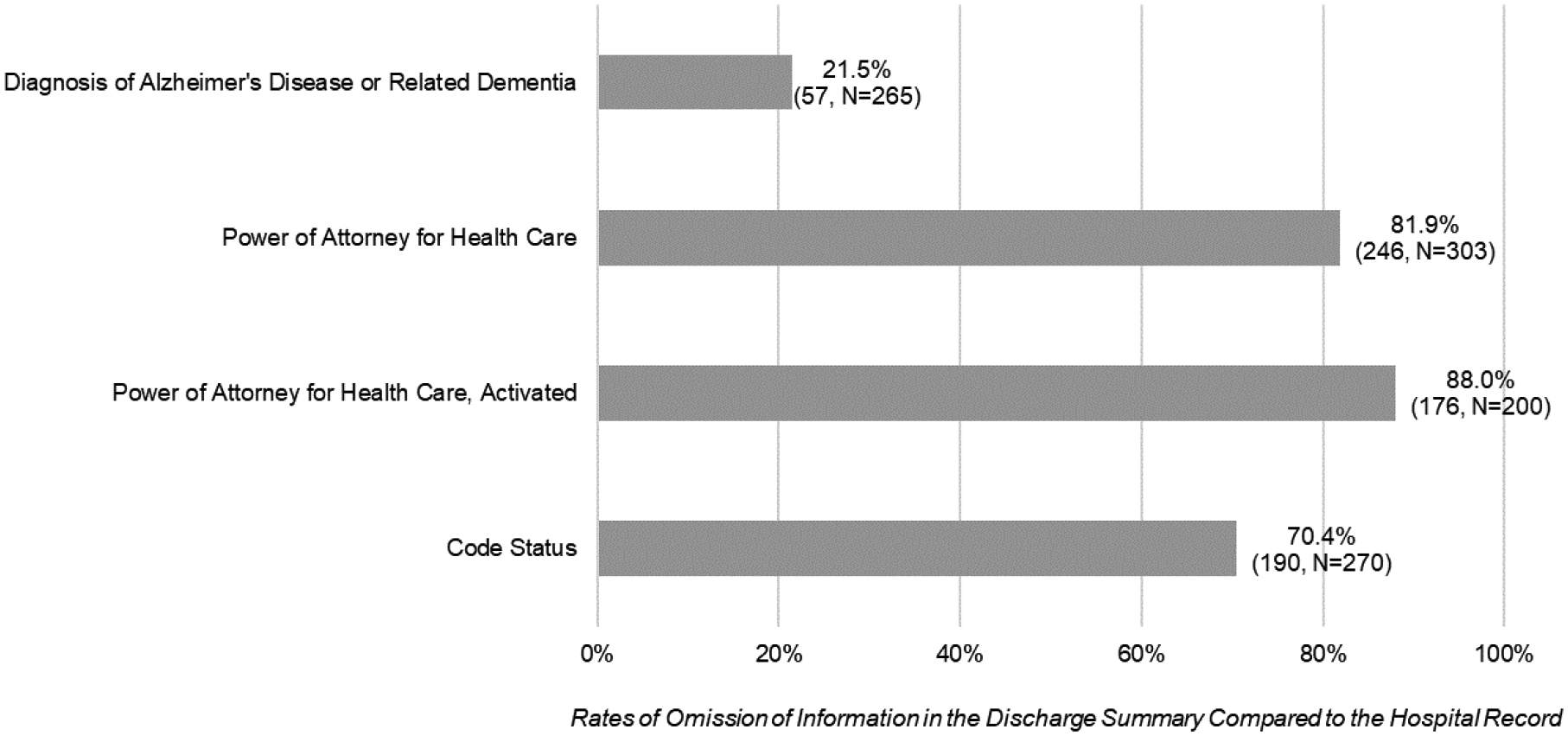

Hospital-to-skilled nursing facility (SNF) transitions constitute a vulnerable point in care for people with dementia and often precede important care decisions. These decisions necessitate accurate diagnostic/decision-making information, including dementia diagnosis, power of attorney for health care (POAHC), and code status; however, inter-setting communication during hospital-to-SNF transitions is suboptimal. This retrospective cohort study examined omissions of diagnostic/decision-making information in written discharge communication during hospital-to-SNF transitions. Omission rates were 22% for dementia diagnosis, 82% and 88% for POAHC and POAHC activation respectively, and 70% for code status. Findings highlight the need to clarify and intervene upon causes of hospital-to-SNF communication gaps.

Keywords: Dementia, Transitional Care, Discharge Summary, Decision-Making

Introduction

People living with dementia experience progressive changes in memory and thinking that impact their ability to make decisions and communicate care needs over time.1 People living with dementia are particularly vulnerable during transitions across care settings as they must rely on others for the transfer of accurate, timely, and complete information and have unique psychiatric and behavioral care needs.2 Transitions between hospitals-and-skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are particularly challenging and common for people with dementia: approximately 34% of hospitalized patients with dementia discharge to SNF settings and two-thirds of long-stay SNF residents experience cyclical transitions to and from the hospital.3,4 Consequences of poorly managed hospital-to-SNF transitions include heightened risk for re-hospitalization, inappropriate care delivery, and avoidable patient and caregiver strain.5–7

In the United States, the written discharge summary, sometimes referred to as written discharge orders, is widely recognized as the primary tool for communication between inpatient and outpatient settings and studied as an important component of transitional care for information continuity.8–11 Studies from a range of clinical conditions have demonstrated that written discharge communication, and in particular accuracy and completeness in the written discharge summary, is associated with superior transitional care quality and patient outcomes in the post-hospital care period.8,12–14

The written discharge summary serves a specific function in relaying information that comprises admitting orders upon the patient’s entry into the SNF.15,16 This function is distinct from yet complements growth in electronic health record (EHR) use and related platform interoperability. To date, hospitals far outpace SNFs in use of EHRs and interoperability efforts,17,18 indicating the continued role of timely and accurate written discharge communication in facilitating information transfer. Using data from 2019 and 2021, the United States Department of Health & Human Services Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) determined that eighty-six percent of general acute care hospitals have an EHR that meets their eight criteria (e.g. privacy and security, clinical quality measurement, care coordination).19,20 The same ONC report determined only 79% of long-term care settings had EHRs that met the same criteria,19 which is consistent with other reports on EHR adoption among SNFs.18 In 2019, 55% of hospitals could perform on all four metrics of interoperability (to send, receive, find, and integrate information into their EHRs) with higher capacity for specific criteria such as sending data (91%) and receiving data (81%).21 SNFs had less the half the capacity on the same metrics of interoperability.22 For example, only 41% of SNFs could receive data into their EHRs, and only 48% had any sources of outside data available.22

Therefore, the written discharge summary remains critically important during hospital-to-SNF transitions as its content shapes immediate SNF decision-making and care planning, particularly in environments where access to clarifying information via EHRs is lacking.6 The Joint Commission, an accrediting body for health care organizations in the United States, mandates that discharge summaries include the following standard components: reason for hospitalization, treatments and procedures, significant findings, condition upon discharge, instructions for patient and/or family, and the signature of the attending physician.10 Yet, multiple studies demonstrate that even the minimal Joint Commission standards are not uniformly met.9,10,23,24

Poor communication of presence of dementia diagnosis and information needed for decisions surrounding hospital-to-SNF transitions has been reported in prior qualitative studies.2 However, the quality of discharge summary communication about essential diagnostic and decision making domains, which would provide insights into features of information discontinuity during these transitions, has not been examined. The minimum necessary information to enable the SNF setting to navigate decisions include presence of a dementia diagnosis which indicates risk for impaired decisional capacity, presence and activation of advanced directes specifically power of attorney for health care, and most recent decisions regarding code status.

Timely, accurate discharge communication regarding documentation and activation of POAHC and code status (i.e. resuscitate, do not resuscitate) is needed immediately upon admission to a SNF, as people with dementia may experience challenges communicating their care preferences, are frequently unaccompanied during transitions, and are at greater risk for adverse and critical events.6,25 Communication of POAHC is particularly important given changes in decisional capacity that accompany dementia over time and the volume of information transfer and decisions during hospital-to-SNF transitions.2,26,27 Designation of a POAHC refers to a written legal document that provides someone with the opportunity to elect a representative, often a family member, to make healthcare-related decisions on their behalf if they were to become unable to do so.28 Knowledge regarding a person living with dementia’s code status is essential to the provision of ethical care that is congruent with their preferences and reduces potentially unnecessary and costly care.29,30 In fact, resuscitation attempts are contraindicated for more than half of people with dementia in SNF environments who have designated a do not resuscitate code status.31

Evaluating omissions of information in written discharge communication is an important target as discharge summaries are immediately actionable upon admission to the SNF setting; information and discharging provider orders located within serve as the admitting orders to the SNF setting upon which plans of care will be implemented.6 These orders may be viable for a substantial period of time, as many patients in this setting are not required to be seen by a physician for up to 30 days after admission particularly if assessed by a physician prior to transfer.32,33 While time to first physician visit for most SNF residents is four days, 10% never receive an assessment and residents with cognitive impairment are more likely to wait or receive no visit,34 which is particularly problematic as half of the SNF resident population has some form of dementia.35

Nurses are the predominant workforce in SNFs and are responsible for designing an individualized care plan and communicating resident care needs to other members of the health care team, based predominantly on information received in the discharge summary.6,23 Despite consistent evidence of information continuity deficits surrounding hospital-to-SNF transitions23,24 and the role of the written discharge summary in facilitating these transitions, few studies examine the quality of the written discharge summary information that is important for the care of people with dementia undergoing a hospital-to-SNF transition. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess quality through calculating rates of omission in written discharge communication for diagnostic information, presence and activation of POAHCs, and code status among people living with dementia during hospital-to-SNF transitions. Comprehensive examination of clinical data linked to discharge summaries is time-intensive and challenging, and can often only occur retrospectively. As such, this study utilizes data from 2003–2009 to examine the completeness of discharge communication of diagnostic and decision-making information for people living with dementia during hospital-to-SNF transitions.

Methods

Design

A multi-site retrospective cohort study design integrating administrative and clinical data sources was used.

Sample

The sample included 343 non-hospice Medicare beneficiaries with dementia, receiving hospital care for a primary diagnosis of stroke or hip/femur fracture who were then subsequently discharged to a SNF.36,37 The stroke and hip/femur fracture diagnoses were utilized to identify a cohort of patients who might require SNF-level care post-hospitalization; these diagnoses are known to increase risk for entry into a SNF setting post-hospitalization.38–40 Once SNF designation was confirmed for these individuals, a smaller cohort of patients with dementia was derived, resulting in the cohort of 343 patients with dementia and stroke or hip/femur fracture.

Patients with a hip fracture and stroke were identified through use of ICD-9 codes (hip fracture: 805.6, 805.7, 806.6, 806.7, 808, and 820; stroke: 431, 432, 434, and 436), and patients with a dementia diagnosis identified through use of ICD-9 codes previously validated by Taylor and colleagues.41

Procedure

Medical record data were abstracted from the EHRs and discharge summaries of two hospitals between 2003–2009. The hospitals are both located in a Midwestern city, approximately 450–500 bed size, and serve large catchment areas discharging patients to at least 51 unique SNFs in surrounding urban and rural contexts, with several more unspecified SNFs. While one hospital examined has academic status, the other is non-for-profit. Medicare data, abstracted EHR documentation and discharge summary data were linked at the patient-level through use of patient Medicare identification number and demographic information. Four trained abstractors completed systematic abstraction of data from the EHR (structured and unstructured data from flowsheets and clinician notes, including the history and physical examination notes, admission notes, progress notes, and therapy notes) and discharge summary using standardized abstraction methods which have been previously described.36,37,42 To ensure accurate abstraction, regular arbitration meetings took place, with coding differences discussed and resolved by a third abstractor, and interrater reliability evaluated for 10% of records via Cohen’s κ. Resultant Cohen’s κ averaged across all abstracted variables was 0.89 with overall agreement at 95%.

Analysis

Omission rates were calculated at the patient level for persons who had dementia diagnosis, presence and/or activation of a POAHC, and code status documented in the hospital EHR but omitted from the discharge summary. For example, for individuals with clinical documentation of dementia diagnosis in the EHR, examination of presence of documentation of a dementia diagnosis was determined to be present or missing from their discharge summary. These analyses use the number of individuals with presence of documentation in their EHR as the denominator. Consequentially, denominators per variable vary provided the requirement of presence of information in the EHR to calculate accurate omission rates at the patient level. Additionally, the number of patients with information available in the EHR and discharge summary differed, which reflects variation in clinical documentation quality.

All analyses were performed in STATA version 15. This study received review and approval from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board.

Results

The sample of patients living with dementia (N=343) had a mean age of 84.5 and was 74.1% female and 11.7% Medicaid status. Patients experienced a mean hospital length of stay of 6 days, 77.4% were hospitalized for hip fracture while 22.7% a stroke, and on average experienced several comorbidities (6.9 Elixhauser Comorbidity Score—higher scores mean more comorbidities;43 1.3 Mean Hierarchical Condition Category—higher scores mean more severe comorbidities).44 Additional sample characteristics are captured in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N=343)

| Characteristic | N = 343 |

|---|---|

| Patient Sociodemographic Characteristics | |

| Age in Years at Discharge, mean (SD)a | 84.45 (6.83) |

| Age, n(%) | |

| <75 years | 22 (6.4) |

| 75–79 years | 53 (15.5) |

| 80–84 years | 83 (24.2) |

| ≥85 years | 185 (53.9) |

| Female, n(%) | 254 (74.1) |

| Medicaid, n(%) | 40 (11.7) |

| Patient Prior Medical History | |

| Index Hospital Length of Stay in Days, mean (SD)b | 6.07 (3.83) |

| 1–4 days | 115 (33.5) |

| 5 days | 77 (22.4) |

| 6–7 days | 91 (26.5) |

| >8 days | 60 (17.5) |

| Primary Diagnosis, n(%) | |

| Stroke | 78 (22.7) |

| Hip Fracture | 265 (77.4) |

| Hierarchical Condition Category, mean (SD) | 1.26 (0.20) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Score, mean (SD) | 6.94 (6.84) |

SD = standard deviation

Median age of 85 (interquartile range=80–89)

Median length of stay of 5 days (interquartile range=4–7)

Clinical Documentation

Of 343 persons with dementia, clinical documentation of an Alzheimer’s disease or dementia diagnosis and POAHC was examined for 338 patients with complete information and code status for 343 patients with dementia with complete information. Of the 338 patients with dementia, clinical documentation of a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia was present for 78.4% (n=265) (Table 2). Of 338 patients with dementia, clinical documentation of a POAHC was present for 89.6% (n=303) with 59.2% (n=200) having an activated POAHC noted. Of 343 patients with dementia, 78.7% (n=270) had clinical documentation of their code status designation.

Table 2.

Patterns in Written Communication of Diagnostic and Decision-Making Information During Hospitalization and Upon Discharge

| Overall (N=338) | Hip Fxb (N=262) | Stroke (N=76) | Overall (N=342) | Hip Fx (N=265) | Stroke (N=77) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease or Dementia | 265 (78.4%) | 214 (81.7%) | 51 (67.1%) | 219 (64.0%) | 173 (65.3%) | 46 (59.7%) |

| Documentation of Power of Attorney for Health Care | 303 (89.6%) | 237 (90.5%) | 66 (86.8%) | 60 (17.5%) | 49 (18.5%) | 11 (14.3%) |

| Documentation of Power of Attorney for Health Care, Activated | 200 (59.2%) | 160 (61.1%) | 40 (52.6%) | 29 (8.5%) | 26 (9.8%) | 3 (3.9%) |

| Code Statusc | 270 (78.7%) | 211 (79.6%) | 59 (75.6%) | 81 (23.6%) | 58 (21.9%) | 23 (29.5%) |

Sample size differs for hospital record and discharge summary

Fx = Fracture

Sample size for code status differs. During hospitalization: Overall n=343, Hip fracture n=265, Stroke n=78. Upon discharge: Overall n=343, Hip fracture n=265, Stroke n=78.

Discharge Summary Communication

Upon discharge, of the 343 patients with dementia in the total sample, discharge communication of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia diagnosis, POAHC, and activated POAHC was examined for 342 individuals while code status was examined for 343 patients. Of these 342 patients with dementia, clinical documentation of an Alzheimer’s disease or dementia diagnosis was present for 64.0% (n=219), POAHC documentation for 17.5% (n=60), activated POAHC documentation for 8.5% (n=29), and code status designation for 23.6% of 343 (n=81). Of the 81 persons with code designation in their written discharge communication, 58% (n=47) had alignment between hospital record and discharge designation. In contrast, of the 81, 9% (n=7) had a potentially major transition between hospital record to written discharge communication, i.e. full code to do no resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI), no record to DNR/DNI, or DNR/DNI to full code. Finally, 33% (n=27) had minor variations when comparing their hospital record to written discharge summary (i.e. transitioning from DNR to DNR/DNI or from DNR to DNR with intubation) or had interchangeable use of no code, DNR, and DNR/DNI between records.

Person-Level Omission Patterns

Of the 265 individuals with clinical documentation of Alzheimer’s or dementia in their EHR, 21.5% (n=57) had this diagnosis omitted upon discharge utilizing a patient-level comparison across EHR and discharge summary. For the 303 persons with a POAHC documented within their EHR, the omission rate upon discharge was 81.9% (n=246). Among the 200 individuals with an activated POAHC documented within their EHR, the omission rate upon discharge was 88.0% (n=176). Of the 270 persons with a code status designation in their medical record, the omission rate upon discharge was 70.4% (n=190) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rates of Omission for Written Communication of Diagnostic and Decision-Making Information across Hospital Record and Discharge Summary

Discussion

This multi-site retrospective cohort study reveals significant gaps in hospital-to-SNF discharge summary communication of essential dementia-specific diagnostic and decision-making support information. Though presence of a dementia diagnosis was only omitted in 21.5% of discharge summaries, this figure still may represent an unacceptable level of under-communication of information highly relevant to care decisions and adequate preparation in the SNF setting. In contrast, details regarding presence and/or activation of POAHC and code status were omitted at strikingly high rates of 81.9%, 88.0% and 70.4% respectively.

Our findings align with recent research revealing consistent gaps in information continuity during hospital-to-SNF transitions,23,24 yet highlight dementia-specific information domains critical for provision of care that aligns with people living with dementia’s preferences and supported decision-making. Missing diagnostic information and details on POAHCs and code status are significant as they may lead to the lack of dementia-sensitive care, poor involvement of family and surrogate decision makers, and misalignment with person with dementia preferences.45,46 Integration of resident preferences and needs into care plans are essential to SNF nurses’ capacity to promote quality of life and confirm adherence to expressed wishes, which remain important targets in SNF environment and are at the center of nursing home culture change movements.47 Providing care that aligns with resident preferences, which often incorporates family involvement and guidance regarding expressed wishes, has implications for resident outcomes as well as family and staff experiences, thereby reducing stress and improving satisfaction with care and performance.45–48 Yet research demonstrates that resident preferences are consistently unmet,46 and omissions in hospital-to-SNF communication may serve as a specific barrier to meeting preferences from the moment of admission.

The findings of this study highlight the continued importance of examining written discharge summaries for completeness of information that is specific to patients with dementia to inform policy and practice changes supportive of improved transitional care for people with dementia. Recent revisions by the Joint Commission mandate hospitals provide patients with opportunities to contribute to the discharge planning process.49 While these revisions represent progress towards patient-centered discharge processes, implementation may be challenging for individuals with dementia who may not be able to communicate needs and preferences, therefore requiring family involvement. Moreover, this revision falls short of recommendations by the experts made through the Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement, which could strengthen inter-setting care communication quality for patients with dementia in particular.50 Criteria examined in this study represent a small portion of information necessary for providing care for individuals living with dementia in alignment with the Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement, for example cognitive status, advance directives, and caregiver status, yet additional information elements are recommended to support transitions for vulnerable populations.50

Future research must consider mechanisms to support the full complexity of patient and family decision making throughout the discharge process—which for patients with dementia, frequently involves multiple care partners beyond the single individual listed in POAHC documentation.51–55 Additionally, even as memory and decision-making capacity decline with disease progression, people living with dementia retain personhood, an ability to express assent and dissent, and engage in supported decision making.56 Given transitions in care may be more complex than singular transitions (i.e. hospital-to-SNF) and rather exist on a continuum (i.e. community-to-hospital-to-SNF-community), additional research is also needed on the nature and extent of communication regarding individual patient and surrogate decision-making preferences and code status across multiple settings of care.

Gaps in discharge communication of POAHCs and code status within the discharge summary reveal the need for additional research on mechanisms by which this information is communicated if not within the discharge plan, along with the associated workflow processes, timeliness, and accuracy. For example, end-of-life care planning tools such as Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) and more novel tools such as longitudinal care plans that move with a person across care settings could facilitate more robust transitions in care, particularly for people with dementia.57,58 Comprehensive and longitudinal communication plans could convey important care preferences beyond legal and decision-making domains, such as psychiatric, behavioral, social, or emotional care needs. Such information could be captured and checked for updates at admission, throughout a stay, and upon discharge.

Basic information may be omitted from the discharge summary by hospital staff for a variety of reasons. First, evidence points towards a lack of training for hospital providers in discharge summary creation, which could be exacerbated for trainees who are often charged with the task or specific specialties who may be following the patient.15,59–61 Second, there may be a lack of understanding of the importance and use of the discharge summary in subsequent settings of care, such as the belief that the discharge summary serves as a record of hospitalization rather than a tool to facilitate handoff and continuity of care.62,63 Similarly, some research demonstrates that hospital and SNF providers do not fully understand respective roles,64 potentially contributing to assumptions that discharge summary orders are not actionable in subsequent settings, that SNF providers will generate or update orders immediately upon admission, or that the SNF already has the required information and orders for returning residents. However, these represent misconceptions given the actionable nature of discharge summary orders upon admission to a SNF compounded by delays in being seen by a SNF provider, the number of new hospital-to-SNF admissions, and the potential for diagnostic and decision-making information to change during hospitalization and surrounding acute illness.6 Additionally, changes to advance directives may be more likely surrounding hospital-to-SNF transitions, influenced by presence of facilitative practices and resources, clinical deterioration or shifts in cognitive abilities, and critical events.65,66 Third, hospital providers and staff may assume interoperability between EHRs, or easy transfer of information between settings. Yet, as described, EHR adoption and interoperability in SNFs continues to lag considerably behind hospitals, and information post-discharge is often transferred via telephone or facsimile.67,68 There are several care processes surrounding discharge that may serve to supplement the discharge summary, including information sent directly from hospital to SNF via email, facsimile, or interoperable EHRs; warm hand-offs and reports; and shared providers.6,23,69 While these touchpoints and processes may ameliorate the gaps within written discharge summary communication, they do not replace the need for written orders or physical copies of legal documents such as activated POAHC and merit further investigation.

As a limitation, data examined in this study are from 2003–2009, and these older data may not reflect the impact of broader EHR adoption and interoperability efforts following the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 and related Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act,70 or incentivized care coordination following the 2009 Affordable Care Act (ACA), which introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP).71 While these data may be older, recent research demonstrates persistent gaps in hospital-to-SNF communication exchange as well as delays in SNF EHR advancement and interoperability,17,18,23,72 highlighting the relevance of our findings for current policy and practice change around the written discharge summary to improve communication of dementia-specific information. As another limitation, the sample included individuals with dementia and a stroke or hip/femure fracture. Given these diagnoses, individuals may have been followed by trainees or specialty providers who then generated the discharge summary with potentially less familiarity to dementia-specific needs.15,59–61

This study has several implications for geropsychiatric nursing practice and research, with nurses representing the backbone of SNF care delivery. Accurate, timely transfer of dementia-specific information can empower nurses to develop care plans, deliver appropriate preference-congruent care, and involve appropriate surrogate decision-makers—all of which can in turn increase nurse satisfaction in their role.6 As SNFs face critical nursing shortages despite increasing resident acuity, greater psychiatric complexity, and limited time with on-site providers, timely communication of this dementia-specific information can decrease the administrative burden on SNF nurses to acquire the information from hospitals or families.73,74 While family members play an incredibly vital role in transitions of care and throughout a person with dementia’s stay at the hospital and SNF alike,75–77 reliance on them for information transfer can be burdensome or even unfeasible in the case of distant or completely absent care networks.77–82 As such, attention to proccesses and policies for generating an accurate, complete, and timely written discharge summary by the hospital provider must remain a priority. Given the formal written discharge summary historically falls under the hospital provider’s purview, hospital nurses have had limited opportunities to contribute to the document itself but rather must fill gaps using surrounding tools and processes.15,59,60 Development of multidisciplinary communication transfer documents and/or integration of nursing assessment and documentation into hospital discharge summaries authored by advanced practice providers could help fill gaps in discharge communication identified by this study. Other solutions include expanding required components within the discharge summary, improving automated processes for discharge summary generation, and ensuring providers receive adequate training on discharge summary creation particularly for vulnerable population. Given challenges in modifying policies regarding the written discharge summary, additional practical solutions for nurses in both hospital and SNF settings are provided in Table 3 to build on strategies nurses already utilize to address gaps in information exchange and support hospital-to-SNF transitions for patient with dementia.23,66,69,83–88

Table 3.

Practical considerations for nurses in hospital and skilled nursing facility environments to optimize accurate transfer of information regarding diagnostic and decision-making preferences for people with dementia

| Considerations for Nurses in the Hospital Environment | Considerations for Nurses in the Skilled Nursing Facility Environment | Gaps in Information Exchange Addressed |

|---|---|---|

For all patients with dementia or suspected dementia, ensure written discharge summary reflects the following dementia-specific information domains:

|

Expand admission tools and checklists to include a section on dementia-specific information comprehensive of these same domains.83* If information is absent, contact the hospital to gather additional information | Accuracy, completeness |

| Throughout hospitalization for people with dementia, ensure changes to POAHC, other advanced directives, and family contact information are documented in appropriate areas of the patient chart, noting that automatically generated discharge summaries often pull only from certain discrete fields and not narrative text fields or notes | Note if discharge summary is a template with little narrative text, that it may have been automatically generated and necessitate further follow-up with the hospital to identify missing information | Accuracy, completeness |

| Confirm code status as a priority information domain, recognizing if code status documentation is pre-hospital it may have changed during hospitalization65,66,84 | Accuracy | |

| Create opportunities for early multidisciplinary contribution to the written discharge summary and/or design a separate multidisciplinary communication transfer document, harnessing nursing assessment and documentation, and knowledge of patient preferences and family involvement83,85* | Promote early multidisciplinary collaboration between hospital and SNF teams, including on-site or telehealth visits at the hospital by SNF staff86 particularly for patients with complex cognitive and behavioral care needs and increased access to acute care EHRs for SNF staff involved in transitions85,86* | Accuracy, completeness, timeliness |

| Review discharge summary before and after transitions to verify the most recent discharge information and orders are present, remove duplicates to reduce confusion, and ensure discharge summary is signed | Accuracy, completeness, timeliness | |

| Engage in warm hand-offs and phone coordination69 | Accuracy, completeness, timeliness | |

| Facilitate shared clinician/staffing models87* | Accuracy, completeness, timeliness | |

POAHC=Power of Attorney for Health Care

These practical considerations may also require broader organizational policy and practice change

Findings from our study provide a preliminary understanding of the quality of hospital-to-SNF communication of dementia diagnosis, POAHCs, and code status; further research is needed to determine the implementation and impact of recent EHR advancements along with staff practices that may fill gaps in communication between hospital and SNFs and across more complex, multi-setting transitions in care.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Hartford Centers of Gerontological Nursing Excellence and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K76AG060005 (Gilmore-Bykovskyi PI) and K23AG034551 (PI Kind). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gleichgerrcht E, Ibáñez A, Roca M, Torralva T, Manes F. Decision-making cognition in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. Nov 2010;6(11):611–23. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Author & Co-Authors, 2017

- 3.Callahan CM, Tu W, Unroe KT, LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Clark DO. Transitions in care in a nationally representative sample of older americans with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Aug 2015;63(8):1495–502. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaugler JE, Yu F, Davila HW, Shippee T. Alzheimer’s disease and nursing homes. Health affairs (Project Hope). Apr 2014;33(4):650–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortinsky RH, Downs M. Optimizing person-centered transitions in the dementia journey: a comparison of national dementia strategies. Health affairs (Project Hope). Apr 2014;33(4):566–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Author & Co-Authors, 2013

- 7.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. Jan 11 2012;307(2):165–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. Feb 28 2007;297(8):831–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med. Aug 2013;8(8):436–43. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kind AJH, Smith MA. Documentation of Mandated Discharge Summary Components in Transitions from Acute to Subacute Care. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 2: Culture and Redesign). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unnewehr M, Schaaf B, Marev R, Fitch J, Friederichs H. Optimizing the quality of hospital discharge summaries-a systematic review and practical tools. Postgrad Med. Aug 2015;127(6):630–9. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2015.1054256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG, et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Ann Pharmacother. Oct 2008;42(10):1373–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansukhani RP, Bridgeman MB, Candelario D, Eckert LJ. Exploring Transitional Care: Evidence-Based Strategies for Improving Provider Communication and Reducing Readmissions. P & T: a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 2015;40(10):690–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Author & Co-Authors, 2018

- 15.Dinescu A, Fernandez H, Ross JS, Karani R. Audit and feedback: an intervention to improve discharge summary completion. J Hosp Med. Jan 2011;6(1):28–32. doi: 10.1002/jhm.831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Author & Co-Authors, 2016

- 17.Tharmalingam S, Hagens S, English S. The Need for Electronic Health Records in Long-Term Care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;234:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vest JR, Jung H-Y, Wiley K Jr., Kooreman H, Pettit L, Unruh MA. Adoption of Health Information Technology Among US Nursing Facilities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2019;20(8):995–1000.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Adoption of Electronic Health Records by Hospital Service Type 2019–2021. Health IT Quick Stat #60. 2022. https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/adoption-electronic-health-records-hospital-service-type-2019-2021 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 2015 Edition Health IT Certification Criteria Final Rule. 2015. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/page/2020-12/ONC_Policy_Infographic_2020_508.pdf

- 21.Johnson C, Pylypchuk Y. Use of Certified Health IT and Methods to Enable Interoperability by U.S. Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals, 2019. Vol. ONC Data Brief. 2021.

- 22.Henry J, Pylypchuk Y, Patel V. Electronic Health Record Adoption and Interoperability among U.S. Skilled Nursing Facilities and Home Health Agencies in 2017. Vol. ONC Data Brief. 2018.

- 23.Adler-Milstein J, Raphael K, O’Malley TA, Cross DA. Information Sharing Practices Between US Hospitals and Skilled Nursing Facilities to Support Care Transitions. JAMA Netw Open. Jan 4 2021;4(1):e2033980. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Author & Co-Authors, 2021

- 25.Kapoor A, Field T, Handler S, et al. Adverse Events in Long-term Care Residents Transitioning From Hospital Back to Nursing Home. JAMA Intern Med. Sep 1 2019;179(9):1254–1261. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegde S, Ellajosyula R. Capacity issues and decision-making in dementia. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2016;19(Suppl 1):S34–S39. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.192890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlawish J Measuring decision-making capacity in cognitively impaired individuals. Neuro-Signals. 2008;16(1):91–98. doi: 10.1159/000109763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately One In Three US Adults Completes Any Type Of Advance Directive For End-Of-Life Care. Health affairs (Project Hope). Jul 1 2017;36(7):1244–1251. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKenzie MA, Smith-Howell E, Bomba PA, Meghani SH. Respecting Choices and Related Models of Advance Care Planning: A Systematic Review of Published Evidence. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2018;35(6):897–907. doi: 10.1177/1049909117745789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholas LH, Bynum JP, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR, Langa KM. Advance directives and nursing home stays associated with less aggressive end-of-life care for patients with severe dementia. Health Aff (Millwood). Apr 2014;33(4):667–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. Feb 9 2004;164(3):321–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimant J. Roles and Responsibilities of Attending Physicians in Skilled Nursing Facilities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2003;4(4):231–243. doi: 10.1016/S1525-8610(04)70355-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United States Government Publishing Office. 42 CFR Part 483.40 – Physician services. 2011. Accessed 20 January 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/pdf/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec483-40.pdf

- 34.Ryskina KL, Yuan Y, Teng S, Burke R. Assessing First Visits By Physicians To Medicare Patients Discharged To Skilled Nursing Facilities. Health affairs (Project Hope). Apr 2019;38(4):528–536. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann F, Kaduszkiewicz H, Glaeske G, van den Bussche H, Koller D. Prevalence of dementia in nursing home and community-dwelling older adults in Germany. Aging Clin Exp Res. Oct 2014;26(5):555–9. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0210-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Author & Co-Authors, 2019

- 37.Author & Co-Authors, 2021

- 38.Hoverman C, Shugarman LR, Saliba D, Buntin MB. Use of postacute care by nursing home residents hospitalized for stroke or hip fracture: how prevalent and to what end? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Aug 2008;56(8):1490–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostwald SK, Godwin KM, Ye F, Cron SG. Serious adverse events experienced by survivors of stroke in the first year following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Rehabilitation nursing : the official journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses. Sep–Oct 2013;38(5):254–63. doi: 10.1002/rnj.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, et al. The Aftermath of Hip Fracture: Discharge Placement, Functional Status Change, and Mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170(10):1290–1299. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor DH, Jr., Ostbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):807–15. doi: 10.3233/jad-2009-1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Author & Co-Authors, 2016

- 43.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. Jan 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Formative Health. Understanding Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC). 2018. Accessed March 30, 2022. http://www.formativhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/HCC-White-Paper.pdf

- 45.Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, Kallmyer B. The Fundamentals of Person-Centered Care for Individuals With Dementia. Gerontologist. Jan 18 2018;58(suppl_1):S10–s19. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duan Y, Shippee TP, Ng W, et al. Unmet and Unimportant Preferences Among Nursing Home Residents: What Are Key Resident and Facility Factors? J Am Med Dir Assoc. Nov 2020;21(11):1712–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: the culture-change movement. Health affairs (Project Hope). Feb 2010;29(2):312–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edvardsson D, Fetherstonhaugh D, Nay R. Promoting a continuation of self and normality: person-centred care as described by people with dementia, their family members and aged care staff. Journal of clinical nursing. Sep 2010;19(17–18):2611–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Joint Commission. Starting May 1: New interoperability, patient access requirements for hospitals, CAHs. 2020. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters/joint-commission-online/april-7-2021/starting-may-1-new-interoperability-patient-access-requirements-for-hospitals-cahs/#.Yljjg-jMLIU

- 50.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. Aug 2009;24(8):971–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Author & Co-Authors, 2021

- 52.Peterson A, Karlawish J, Largent E. Supported Decision Making With People at the Margins of Autonomy. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2021/11/02 2021;21(11):4–18. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1863507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bosco A, Schneider J, Coleston-Shields DM, Jawahar K, Higgs P, Orrell M. Agency in dementia care: systematic review and meta-ethnography. Int Psychogeriatr. May 2019;31(5):627–642. doi: 10.1017/s1041610218001801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee S, Kirk A, Kirk EA, Karunanayake C, O’Connell ME, Morgan D. Factors Associated with Having a Will, Power of Attorney, and Advanced Healthcare Directive in Patients Presenting to a Rural and Remote Memory Clinic. Can J Neurol Sci. May 2019;46(3):319–330. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2019.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinclair C, Gersbach K, Hogan M, et al. How couples with dementia experience healthcare, lifestyle, and everyday decision-making. Int Psychogeriatr. Nov 2018;30(11):1639–1647. doi: 10.1017/s1041610218000741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hegde S, Ellajosyula R. Capacity issues and decision-making in dementia. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. Oct 2016;19(Suppl 1):S34–s39. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.192890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim H, Ersek M, Bradway C, Hickman SE. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment for nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. Nov 2015;27(11):606–14. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dykes PC, Samal L, Donahue M, et al. A patient-centered longitudinal care plan: vision versus reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. Nov-Dec 2014;21(6):1082–90. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Axon RN, Penney FT, Kyle TR, et al. A Hospital Discharge Summary Quality Improvement Program Featuring Individual and Team-based Feedback and Academic Detailing. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2014/06/01/ 2014;347(6):472–477. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Sattin JA, Walz SE, Smith MA. Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med. Jan 2012;27(1):78–84. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1860-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kable A, Chenoweth L, Pond D, Hullick C. Health professional perspectives on systems failures in transitional care for patients with dementia and their carers: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Services Research. 2015/12/18 2015;15(1):567. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1227-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yemm R, Bhattacharya D, Wright D, Poland F. What constitutes a high quality discharge summary? A comparison between the views of secondary and primary care doctors. International journal of medical education. 2014;5:125–131. doi: 10.5116/ijme.538b.3c2e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lenert LA, Sakaguchi FH, Weir CR. Rethinking the discharge summary: a focus on handoff communication. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014;89(3):393–398. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valverde PA, Ayele R, Leonard C, Cumbler E, Allyn R, Burke RE. Gaps in Hospital and Skilled Nursing Facility Responsibilities During Transitions of Care: a Comparison of Hospital and SNF Clinicians’ Perspectives. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2021/08/01 2021;36(8):2251–2258. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06511-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van der Steen JT, van Soest-Poortvliet MC, Hallie-Heierman M, et al. Factors associated with initiation of advance care planning in dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40(3):743–57. doi: 10.3233/jad-131967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jain VG, Greco PJ, Kaelber DC. Code Status Reconciliation to Improve Identification and Documentation of Code Status in Electronic Health Records. Appl Clin Inform. Mar 8 2017;8(1):226–234. doi: 10.4338/aci-2016-08-ra-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alvarado CC, Zook K, & Henry J Electronic health record adoption and interoperability among U.S. skilled nursing facilities in 2016. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 2017. Accessed 20 January 2022. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/electronic-health-record-adoption-and-interoperability-among-u.s.-skilled-nursing-facilities-in-2016.pdf

- 68.Samal L, Dykes PC, Greenberg JO, et al. Care coordination gaps due to lack of interoperability in the United States: a qualitative study and literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. Apr 22 2016;16:143. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1373-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Campbell Britton M, Hodshon B, Chaudhry SI. Implementing a Warm Handoff Between Hospital and Skilled Nursing Facility Clinicians. J Patient Saf. Sep 2019;15(3):198–204. doi: 10.1097/pts.0000000000000529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.US Department of Health and Human Services. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, 42 U.S.C. § 201. 2010. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap6A-subchapI-sec201/summary

- 71.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). 2019. Accessed 20 January 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program

- 72.Devers K, Lallemand N, Napoles A, Spillman B, Blaven F, & Ozanich G Health Information Exchange in Long-Term and Post-Acute Care Settings. Prepared for the Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/205271/LTPACsetting.pdf

- 73.Harrington C, Schnelle JF, McGregor M, Simmons SF. The Need for Higher Minimum Staffing Standards in U.S. Nursing Homes. Health Serv Insights. 2016;9:13–9. doi: 10.4137/hsi.S38994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White EM, Kosar CM, Rahman M, Mor V. Trends In Hospitals And Skilled Nursing Facilities Sharing Medical Providers, 2008–16. Health affairs (Project Hope). Aug 2020;39(8):1312–1320. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen LW, Zimmerman S, Reed D, et al. Dementia in relation to family caregiver involvement and burden in long-term care. J Appl Gerontol. Aug 2014;33(5):522–40. doi: 10.1177/0733464813505701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Puurveen G, Baumbusch J, Gandhi P. From Family Involvement to Family Inclusion in Nursing Home Settings: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis. J Fam Nurs. Feb 2018;24(1):60–85. doi: 10.1177/1074840718754314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naylor MD, Shaid EC, Carpenter D, et al. Components of Comprehensive and Effective Transitional Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jun 2017;65(6):1119–1125. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chamberlain S, Baik S, Estabrooks C. Going it Alone: A Scoping Review of Unbefriended Older Adults. Can J Aging. Mar 2018;37(1):1–11. doi: 10.1017/s0714980817000563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chamberlain SA, Duggleby W, Fast J, Teaster PB, Estabrooks CA. Incapacitated and Alone: Prevalence of Unbefriended Residents in Alberta Long-Term Care Homes. SAGE Open. 2019/10/01 2019;9(4):2158244019885127. doi: 10.1177/2158244019885127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Shield R, et al. Lost in Transition: a Qualitative Study of Patients Discharged from Hospital to Skilled Nursing Facility. J Gen Intern Med. Jan 2019;34(1):102–109. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4695-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hirschman KB, Hodgson NA. Evidence-Based Interventions for Transitions in Care for Individuals Living With Dementia. Gerontologist. Jan 18 2018;58(suppl_1):S129–s140. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naylor M, Keating SA. Transitional care. Am J Nurs. Sep 2008;108(9 Suppl):58–63; quiz 63. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336420.34946.3a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jeffs L, Kuluski K, Law M, et al. Identifying Effective Nurse-Led Care Transition Interventions for Older Adults With Complex Needs Using a Structured Expert Panel. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. Apr 2017;14(2):136–144. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim YS, Escobar GJ, Halpern SD, Greene JD, Kipnis P, Liu V. The Natural History of Changes in Preferences for Life-Sustaining Treatments and Implications for Inpatient Mortality in Younger and Older Hospitalized Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. May 2016;64(5):981–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Campbell Britton M, Petersen-Pickett J, Hodshon B, Chaudhry SI. Mapping the care transition from hospital to skilled nursing facility. J Eval Clin Pract. Jun 2020;26(3):786–790. doi: 10.1111/jep.13238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lawrence E, Casler JJ, Jones J, et al. Variability in skilled nursing facility screening and admission processes: Implications for value-based purchasing. Health Care Manage Rev. Oct/Dec 2020;45(4):353–363. doi: 10.1097/hmr.0000000000000225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adler-Milstein J, Raphael K, O’Malley TA, Cross DA. Information Sharing Practices Between US Hospitals and Skilled Nursing Facilities to Support Care Transitions. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(1):e2033980–e2033980. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuluski K, Peckham A, Gill A, et al. What is Important to Older People with Multimorbidity and Their Caregivers? Identifying Attributes of Person Centered Care from the User Perspective. Int J Integr Care. Jul 23 2019;19(3):4. doi: 10.5334/ijic.4655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]