Abstract

Protein kinases are responsible for protein phosphorylation and are involved in important signal transduction pathways; however, a considerable number of poorly characterized kinases may be involved in neuronal development. Here, we considered cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK) as a candidate regulator of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis by examining the effects of the selective GAK inhibitor SGC-GAK-1. SGC-GAK-1 treatment of cultured neurons reduced neurite length and decreased synapse number and phosphorylation of neurofilament 200-kDa subunits relative to the control. In addition, the related kinase inhibitor erlotinib, which has distinct specificity and potency from SGC-GAK-1, had no effect on neurite growth, unlike SGC-GAK-1. These results suggest that GAK may be physiologically involved in normal neuronal development, and that decreased GAK function and the resultant impaired neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis may be related to neurodevelopmental disorders.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13041-022-00951-6.

Keywords: Cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK), SGC-GAK-1, Primary neuron culture, High content screening

Phosphorylation is considered to be the most important protein modification in signal transduction pathways. Protein kinases are the responsible enzymes for this process, and there are more than 500 species of kinases encoded in the human genome [1]. However, most of these are not well characterized, and their exact biological roles or functions are not known. Neurons have more complex signaling pathways than other cells because of their role in synaptic plasticity [2], and there are potentially numerous events that involve uncharacterized protein kinases. For example, c-jun N-terminus protein kinase (JNK) is reported to be tightly related to axon growth and regeneration [3].

Cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK) is one such kinase that is not well characterized. This protein is a 160 kDa serine/threonine kinase, and the structure is comprised of a kinase domain at the N-terminus, a PTEN-like domain, a clathrin binding domain, and a C-terminal J domain [4, 5]. Neuron-specific GAK knockouts cause defects in the proliferation of neural progenitor cells in the hippocampal region, causing neuronal depletion and changes in brain morphology, and mouse pups were observed to survive only a few days after birth [6]. However, the effects of GAK on neurodevelopmental processes have not been well investigated. Therefore, we used SGC-GAK-1, which had an IC50 of 48 nM in the live cell target engagement assay [7, 8].

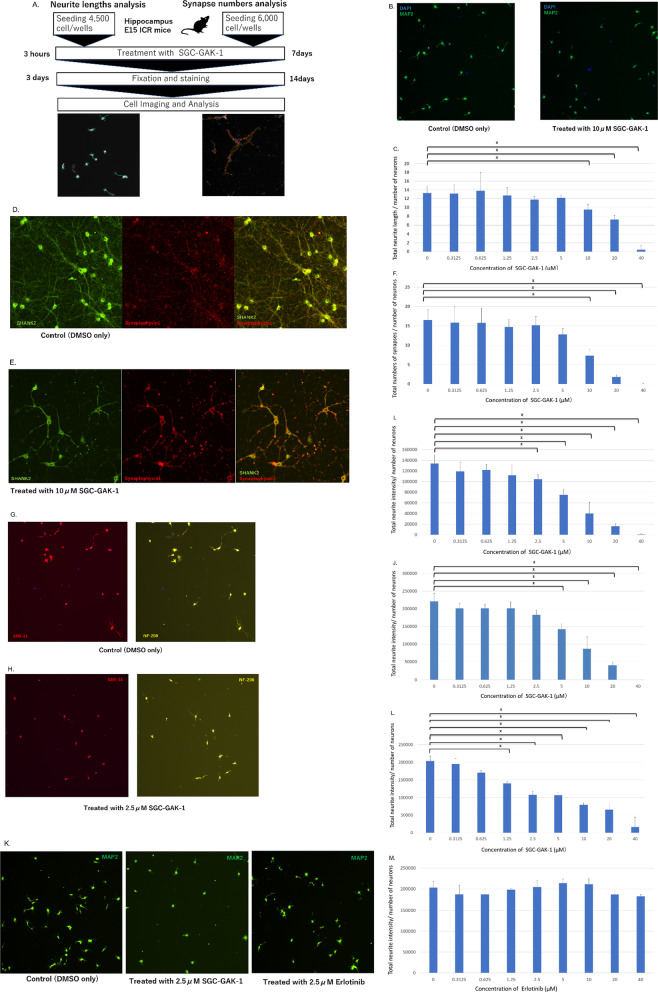

The experimental procedures are described in detail in Additional file 1. We investigated how selective inhibition of GAK using SGC-GAK-1 [9–12] affects neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis in mouse hippocampal neurons, according to the scheme shown in Fig. 1A. For quantification, a high-throughput screening system, the microscope-based CellInsight™ CX5 High Content Screening platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was used. First, we compared the total neurite length per number of neurons of samples treated with eight concentrations of SGC-GAK-1 compared to the control as above. Total neurite length per number of neurons was significantly reduced at 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM SGC-GAK-1 compared to the control supplemented with DMSO alone (p < 0.05/8; Fig. 1B, C). Total neurite branch points per number of neurons were also significantly reduced at 10, 20, and 40 μM SGC-GAK-1 compared to the control supplemented with DMSO alone (p < 0.05/8; Additional file 2: Fig. S1). There was no significant difference in the number of neurons from 0.3125 to 10 μM SGC-GAK-1 compared to the control (Additional file 1: Table S1). In addition, we measured synapse formation using double-immunostaining of synaptophysin (presynaptic marker) and SHANK2 (postsynaptic marker), and the total number of synapses per number of neurons was also significantly reduced at 10, 20, and 40 μM SGC-GAK-1 compared to the control (DMSO alone; p < 0.05/8; Fig. 1D–F). There was also no significant difference in the number of neurons from 0.3125 to 5.0 μM SGC-GAK-1 compared to the control (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of GAK inhibition on neurodevelopment in mice. A Outline of the procedure. The ROI is shown within the yellow dotted curves, in which synaptic puncta were quantified (Right). B Cell imaging of neurons treated with 10 μM SGC-GAK-1 or dimethysulfoxide (DMSO) as the control. C Total neurite length per number of neurons in samples treated with 0.3125, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM SGC-GAK-1 or DMSO (N = 6, each concentration). D Cell imaging of neurons treated with DMSO and stained with anti-synaptophysin 1 and anti-SHANK2 antibodies. E Cell imaging of neurons treated with 10 μM SGC-GAK-1 and stained with anti-synaptophysin 1 and anti-SHANK2 antibodies. F Total number of synapses per number of neurons in samples treated with SGC-GAK-1 (same concentrations as in C) or DMSO (N = 6, each concentration). G Cell imaging of neurons treated with DMSO and stained with SMI-31 or NF-200. H Cell imaging of neurons treated with 2.5 μM SGC-GAK-1 and stained with SMI-31 or NF-200. I SMI-31 staining: Neurite intensity per number of neurons in samples treated with SGC-GAK-1 (same concentrations as in C) or DMSO. J NF200 staining: Neurite intensity per number of neurons in samples treated with SGC-GAK-1 (same concentrations as in C) or DMSO (N = 3, each concentration). K Cell imaging of neurons treated with 2.5 μM SGC-GAK-1, 2.5 μM erlotinib, or DMSO and stained with MAP2. L SGC-GAK-1 treatment: Neurite intensity per number of neurons (stained with MAP2) in samples treated with SGC-GAK-1 (same concentrations as in C and N = 3, each concentration) or DMSO (N = 6). M Erlotinib treatment: Neurite intensity per number of neurons (stained with MAP2) in samples treated erlotinib (N = 3, each concentration, which is the same as in C) or DMSO (N = 6). Image size: 899.04 µm × 899.04 µm (B, G, H, K); 455.44 µm × 455.44 µm (D, E). Total neurite length/number of neurons, total number of synapses/number of neurons, and total neurite intensity/number of neurons were significant (*) at p < 0.05/8 after Bonferroni’s correction and the error bars indicate standard deviation

Next, we immunostained the cultured neurons after exposure to SGC-GAK-1, using NF-200 and SMI-31 antibodies specific to the phosphorylated neurofilament (NF)-200 kDa subunit, and analyzed the immunoreactivity intensity in neurites. In both SMI-31 and NF-200 staining, the neurite intensity decreased in proportion to the increase in SGC-GAK-1 concentration (p < 0.05/8). However, at 2.5 μM, a significant difference was observed only in the intensity of SMI-31 compared to the control (Fig. 1G–J). The result showed that SGC-GAK-1 inhibits the phosphorylation function of GAK even in the concentration range with low neuronal cytotoxicity. Thus, we concluded that phosphorylation of the NF-200 kDa subunit was inhibited by SGC-GAK-1 in growing neurites.

We compared the neurite intensity of neurons treated with SGC-GAK-1 and erlotinib, another protein kinase inhibitor structurally related to SGC-GAK-1 but with lower specificity to GAK [10, 13]. Neurons were treated with erlotinib as described for SGC-GAK-1. In neurons treated with 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 μM SGC-GAK-1, the neurite intensity significantly decreased compared to the control (p < 0.05/8). Among them, there were no significant differences in the number of neurons for the 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μM concentrations (Fig. 1K–M). The results showed that SGC-GAK-1 more specifically affected neuronal development involving GAK than did erlotinib. SGC-GAK-1 is a specific inhibitor of GAK, making it an ideal choice for assessing GAK activity. The narrow kinome spectrum and potent cell target engagement make it a better choice for deconvoluting GAK biology than a clinical kinase inhibitor such as erlotinib, which primarily targets EGF receptor tyrosine kinases and has off-target effects on GAK [10, 13]. Erlotinib did not show effects similar to those of SGC-GAK-1 (Fig. 1K–M), indicating that the latter inhibitor affected neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis via GAK specifically.

Neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders, which affect communication, cognition, social interaction, and other patterned behaviors, are currently known to be caused partly by genetic mutations of brain signaling molecules [14] including protein kinases [15]. As shown here, GAK is involved in the normal development of neurons, suggesting the possibility that this or related kinases play a role in the pathogenesis of such diseases. Previously, GAK was reported to be related to neuronal degeneration in Parkinson’s disease by its enhancement of α-synuclein-mediated toxicity [16, 17]; however, no evidence for its relationship to neuronal development has been demonstrated to date. Clathrin adapter proteins were reported to be potential substrates for this kinase in in vitro experiments [18], and an ongoing search for other physiological and specific substrates for this kinase is needed.

In conclusion, using the high-throughput imaging quantification system, we showed that axon outgrowth and synaptogenesis are impeded by inhibiting the phosphorylation function of GAK. It was also demonstrated that SGC-GAK-1 inhibits the substrate phosphorylation function of GAK, and affects neurodevelopment to a greater extent than erlotinib. The novel findings of the present study demonstrated that reduced GAK function is associated with neurodevelopmental disorders as well as α-synuclein-mediated neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. The number of neurons

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Neurite branches were inhibited by SGC-GAK-1.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professor John L. Bixby (Miami University Miller School of Medicine) for the informative discussions.

Author contributions

JE planned and designed the experiments, designed and directed the project, performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. RKA performed the experiments. VPL planned and designed the experiments, designed and directed the project, and wrote the manuscript. MMB performed the experiments. YS analyzed the data. MI planned and designed the experiments, designed and directed the project, and wrote the manuscript. TS directed the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (#20H03597 to TS, #21K07496 to JE, and #18H04013 to MI), AMED-CREST (#21gm1210007s0103 and #22gm1210007s0104 to MI), the NIH (NINDS R01NS100531 to VPL), the State of Florida (to VPL), the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis (to VPL), and the W.G. Ross Foundation (to VPL).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were performed following approval from the Animal Resource Center of Niigata University.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jun Egawa, Email: jeg5414@med.niigata-u.ac.jp.

Michihiro Igarashi, Email: tarokaja@med.niigata-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Graves LM, Duncan JS, Whittle MC, Johnson GL. The dynamic nature of the kinome. Biochem J. 2013;450:1–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer KU, Schulman H. CaM kinase: still inspiring at 40. Neuron. 2019;103:380–394. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawasaki A, Okada M, Tamada A, Okuda S, Nozumi M, Ito Y, Kobayashi D, Yamasaki T, Yokoyama R, Shibata T, Nishina H, Yoshida Y, Fujii Y, Takeuchi K, Igarashi M. Growth cone phosphoproteomics reveals that GAP-43 phosphorylated by JNK is a marker of axon growth and regeneration. iScience. 2018;4:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dzamko N, Zhou J, Huang Y, Halliday GM. Parkinson's disease-implicated kinases in the brain; insights into disease pathogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014;7:57. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang CX, Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Carreno S, Owen DJ, Smythe E, Drubin DG. Multiple roles for cyclin G-associated kinase in clathrin-mediated sorting events. Traffic. 2005;6:1103–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee DW, Zhao X, Yim YI, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Essential role of cyclin-G-associated kinase (Auxilin-2) in developing and mature mice. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2766–2776. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-11-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asquith CRM, Berger BT, Wan J, Bennett JM, Capuzzi SJ, Crona DJ, Drewry DH, East MP, Elkins JM, Fedorov O, et al. SGC-GAK-1: a chemical probe for Cyclin G Associated Kinase (GAK) J Med Chem. 2019;62:2830–2836. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P, Cross D, Jänne PA. Kinase drug discovery 20 years after imatinib: progress and future directions. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:551–569. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asquith CRM, Bennett JM, Su L, Laitinen T, Elkins JM, Pickett JE, Wells CI, Li Z, Willson TM, Zuercher WJ. Towards the development of an in vivo chemical probe for Cyclin G associated kinase (GAK) Molecules. 2019;24:4016. doi: 10.3390/molecules24224016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asquith CRM, Naegeli KM, East MP, Laitinen T, Havener TM, Wells CI, Johnson GL, Drewry DH, Zuercher WJ, Morris DC. Design of a Cyclin G associated kinase (GAK)/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor set to interrogate the relationship of EGFR and GAK in Chordoma. J Med Chem. 2019;62:4772–4778. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asquith CRM, Treiber DK, Zuercher WJ. Utilizing comprehensive and mini-kinome panels to optimize the selectivity of quinoline inhibitors for cyclin G associated kinase (GAK) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2019;29:1727–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asquith CRM, Laitinen T, Bennett JM, Wells CI, Elkins JM, Zuercher WJ, Tizzard GJ, Poso A. Design and analysis of the 4-anilinoquin(az)oline kinase inhibition profiles of GAK/SLK/STK10 using quantitative structure-activity relationship. ChemMedChem. 2020;15:26–49. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201900521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addeo R, Zappavigna S, Parlato C, Caraglia M. Erlotinib: early clinical development in brain cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23:1027–1037. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.918950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Zou H, Brown WT. Genes associated with autism spectrum disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2012;88:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boksha IS, Prokhorova TA, Tereshkina EB, Savushkina OK, Burbaeva GS. Protein phosphorylation signaling cascades in autism: the role of mTOR pathway. Biochem Mosc. 2021;86:577–596. doi: 10.1134/S0006297921050072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beilina A, Rudenko IN, Kaganovich A, Civiero L, Chau H, Kalia SK, Kalia LV, Lobbestael E, Chia R, Ndukwe K, Ding J, Nalls MA, International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium. North American Brain Expression Consortium. Olszewski M, Hauser DN, Kumaran R, Lozano AM, Baekelandt V, Greene LE, Taymans JM, Greggio E, Cookson MR. Unbiased screen for interactors of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 supports a common pathway for sporadic and familial Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2626–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318306111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumitriu A, Pacheco CD, Wilk JB, Strathearn KE, Latourelle JC, Goldwurm S, Pezzoli G, Rochet JC, Lindquist S, Myers RH. Cyclin-G-associated kinase modifies alpha-synuclein expression levels and toxicity in Parkinson's disease: results from the Gene PD Study. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1478–1487. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umeda A, Meyerholz A, Ungewickell E. Identification of the universal cofactor (auxilin 2) in clathrin coat dissociation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:336–342. doi: 10.1078/S0171-9335(04)70037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. The number of neurons

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Neurite branches were inhibited by SGC-GAK-1.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.