Abstract

Neurological vertigo is a common symptom in children and adults presenting to the emergency department (ED) and its evaluation may be challenging, requiring often the intervention of different medical specialties. When vertigo is associated with other specific symptoms or signs, a differential diagnosis may be easier. Conversely, if the patient exhibits isolated vertigo, the diagnostic approach becomes complex and only through a detailed history, a complete physical examination and specific tests the clinician can reach the correct diagnosis. Approach to vertigo in ED is considerably different in children and adults due to the differences in incidence and prevalence of the various causes. The aim of this systematic review is to describe the etiopathologies of neurological vertigo in childhood and adulthood, highlighting the characteristics and the investigations that may lead clinicians to a proper diagnosis. Finally, this review aims to develop an algorithm that could represent a valid diagnostic support for emergency physicians in approaching patients with isolated vertigo, both in pediatric and adult age.

Keywords: Vertigo, Adulthood, Childhood, Emergency department

Introduction

Vertigo can be defined as a disorder of space sensitivity classically described as an unpleasant illusion of motion of the patient or the environment [1–3]. It is an acute and severe symptom that may affect quality of life provoking significant apprehension along with significant occupational impacts. It is a common reason for ED presentation and can be isolated or associated with other symptoms. Conversely, dizziness is a different sensation that can be described as an altered spatial perception without a false sense of motion [3]. Vertigo and dizziness might often be confused by patients and clinician; however the former often refers to an objective sense of external motion, while the latter refers to a subjective sense of instability.

Although vertigo is usually a symptom of peripheral causes as opposed to dizziness, neurological conditions may often presented with vertigo and the spectrum of differential diagnoses is broad and different for adult and pediatric population. The main causes of adulthood neurological vertigo, primarily represented by acute vascular injuries, are uncommon or totally absent in childhood [4, 5]. Moreover several peculiar etiologies of the pediatric neurological vertigo, as opposed to adults, are characterized by favorable prognosis [6]. Hence, the diagnosis is challenging, especially when the vertigo is the only clinical sign at the onset of the symptomatology [7].

A proper diagnostic evaluation essentially includes a stepwise detailed history, a careful physical examination and further tests based on clinical indications [4]. A meticulous medical history taking is the first step to distinguish the peripheral causes of vertigo from the central ones. Assessing intensity, timing and triggers of vertigo may be helpful, even if this approach shows major limitations [8]. For example, patients with acute, spontaneous, isolated vertigo may suffer either from acute vestibular neuritis/labyrinthitis or cerebellar stroke. Conversely, patients with spontaneous, episodic vertigo may be affected by vestibular migraine (VM) but also suffer from recurrent, stereotyped transient ischemic attacks [9]. In adults positional vertigo, mainly attributed to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), may also have a central origin, especially when persistent and associated with nystagmus [9]. Another aspect to be investigated is the presence of concurrent symptoms; however, they are often misleading or missing initially (e.g. headache in VM, hypoacusis in anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) strokes) [8]. In terms of physical examination it is mandatory to assess the presence of nystagmus which may be horizontal, exhaustible, inhibited by fixation and worsened by head shaking in the peripheral forms, while it is commonly vertical or rotatory in the central ones [10]. The causative origin of vertigo may also be evaluated using diagnostics indexes that combine both history and patients’ clinical characteristics (e.g., ABCD2, CATCH2, STANDING scores) [8]. Lastly, advanced examinations may be crucial, such as the association of normal vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) with head impulse testing (HIT), gaze-evoked nystagmus and the presence of skew deviation at the test of skew (HINTS) that suggests a central cause of vertigo [11].

To date few studies have tried to validate specific diagnostic approaches for neurological vertigo and, in particular for patients with vertigo as exclusive clinical manifestation, there are no standardized diagnostic algorithms [4]. The aim of this systematic review is to identify and describe the characteristics of the neurological disorders presenting, at the onset, with isolated vertigo in childhood and adulthood and to propose a diagnostic algorithm to help clinicians working in ED.

Methods

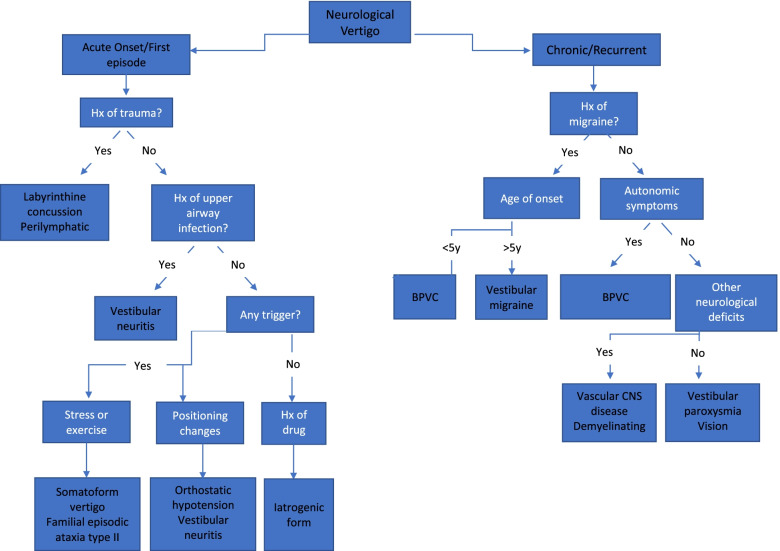

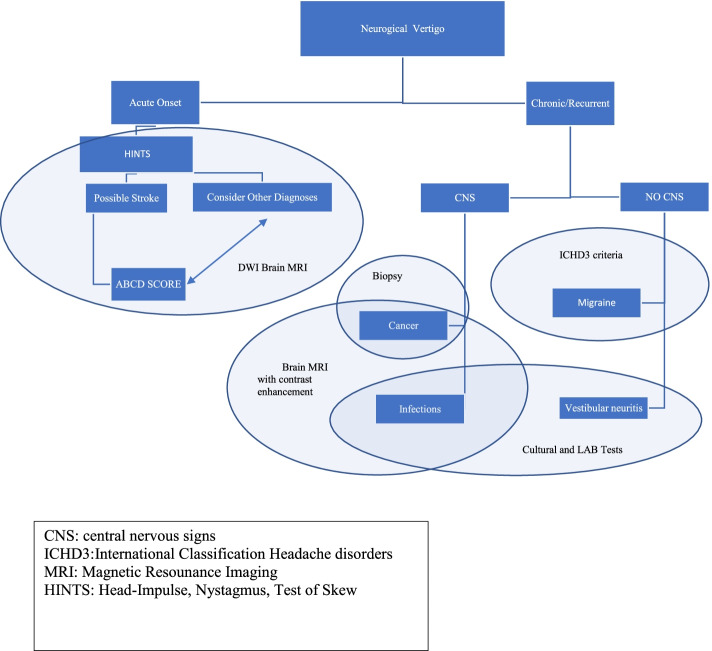

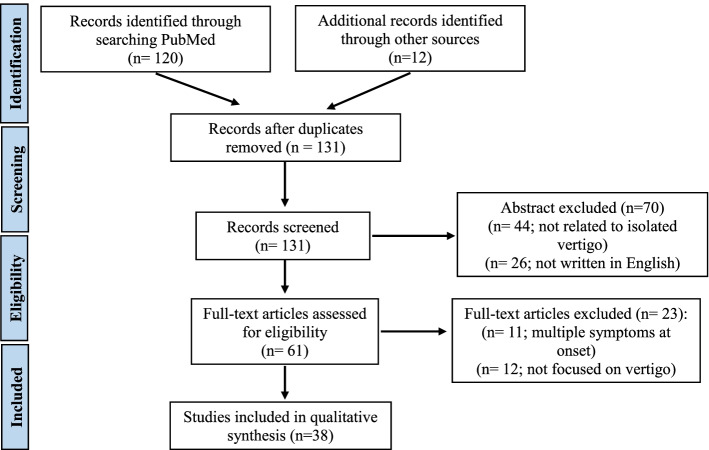

We carried out a systematic review of the literature using PubMed/NCBI database, through a comprehensive MEDLINE search, in order to identify all the available studies describing the isolated neurological vertigo. The following search words were used: “isolated neurological vertigo” and “isolated vertigo children”. The search was conducted between May 19th, 2020 and July 10th, 2020 and it collected studies published between March 1989 and July 2020. We included all original articles (case reports, case series, prospective and retrospective observational studies) written in English, in which subjects presented with isolated vertigo. Our research included not only diseases characterized by vertigo as the only clinical manifestation, but also all the potential causes that, even if usually associated with other symptoms, may initially present with vertigo as exclusive complaint or could be associated to signs highlighted only during the clinical examination. We included studies involving both pediatric and adult population. All the reviewers worked independently in selecting the studies and extracting information about epidemiological, clinical and diagnostic features of patients presenting with isolated vertigo. Finally, we proposed two distinct diagnostic algorithms to ascertain the differential diagnosis of isolated neurological vertigo in pediatric (Fig. 1) and adult (Fig. 2) patients, using key elements of the history and physical examination.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for evaluation of neurological vertigo in children

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for evaluation of neurological vertigo in adults

Results

Our research yielded overall 120 abstracts and a further 12 papers were later added following an additional screening of references from unselected papers. After checking for duplicates we excluded 70 records by reviewing articles’ abstracts. After a detailed examination of the full texts of the 61 remaining articles, we found 38 papers meeting our inclusion/exclusion criteria, which were subsequently included in the qualitative synthesis, 12 related to pediatric patients and 26 related to adult ones (Fig. 3, Tables 1 and 2). We found that isolated vertigo is associated with several adult and pediatric diseases, that are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Fig. 3.

PRISMA diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected pediatric studies

| Study, country | Age range | Study design | Time frame | No. of subjects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lanzi G. et al., 1994 [12] Italy |

12.5 to 24.2 years. old | Prospective study | Not specified | 47 | Vertigo is a rare symptom in patients with juvenile migraine |

|

Salman MS. et al., 2017 [13] Canada |

6 to 32.75 years old | Retrospective study | 1991 to 2008 | 185 | Vertigo/dizziness are often associated with chronic ataxia. Genetic, metabolic and inflammatory disorders should be considered in these patients |

|

Langhagen T. et al., 2013 [14] Germany |

1.4 to 18 years old | Retrospective study | November 2009 to April 2012 | 168 | Migraine-related vertigo is the most common cause of vertigo and dizziness in children and adolescents |

|

Ramantani G. et al., 2009 [15] Germany |

9 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 | Episodes of vertigo can be rarely associated with tuberous sclerosis |

|

Caldarelli M. et al., 2007 [16] Italy |

2 months to 16 years | Retrospective study | January 1993 to August 2005 | 30 | Vertigo is a complaint presenting in 30% of pediatric patients with symptomatic Chiari malformation Type I |

|

Kalashnikova LA. et al., 2005 [17] Russia |

7 to 72 years | Retrospective study | Not specified | 25 | A sudden onset of vertigo can be a clinical manifestation of cerebellar infarcts |

|

Bucci MP. et al., 2004 [18] France |

6 to 15 years old | Prospective study | Not specified | 12 | Vertigo in children with normal vestibular function can be associated with abnormal vergence latency |

|

Russell G. et al., 2009 [19] Scotland |

School age | Epidemiological study | Not specified | 2165 | Paroxysmal vertigo is common in childhood and it appears to cause few major problems to the affected children |

|

D’Agostino R. et al., 1997 [1] Italy |

4 to 14 years old | Retrospective study | 1985 to 1989 | 282 | Vertigo as isolated symptom is the most frequent clinical presentation in childhood. Paroxysmal benign vertigo is the second most frequent cause of vertigo |

|

Raucci U. et al., 2015 [7] Italy |

3 to 18 years old | Retrospective study | January 2009 to December 2013 | 616 | Vertigo is most frequently related to benign conditions such as migraine and syncope. Early recognition of associated signs or symptoms is mandatory to identify need for further investigations |

|

Lehnen N. et al., 2015 [20] Germany |

8 to 12 years old | Case report | 10-year period | 3 | Vestibular paroxysmia should be considered in children with short, frequent vertiginous episodes |

|

Mugundhan K. et al., 2011 [21] India |

13 to 65 years old | Case report | Not specified | 5 | The presence of recurrent episodes of vertigo is typical in familial episodic ataxia type II. Cerebellar function tests can be completely normal between the attacks |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the selected adult studies

| Study, country | Age range | Study design | Time frame | No. of subjects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Joshi P. et al., 2020 [22] New Zealand |

28 to 65 years old | Case series | Not specified | 7 | BPPV is the most common cause of positional vertigo |

|

Grad A. et al., 1989 [23] USA |

40 to 81 years old | Retrospective study | 1974 to 1987 | 84 | The sudden onset of vertigo lasting minutes in a patient with known cerebrovascular disease strongly suggests an ischemic cause |

|

Norrving B. et al., 1995 [24] Sweden |

50 to 75 years old | Prospective study | Not specified | 24 | A caudal cerebellar infarction may easily be misdiagnosed as a labyrinthine disorder, and it is found to be the cause in one in fourpatients presenting with isolated acute vertigo |

|

Kim GW. et al., 1996 [25] Korea |

Not specified | Prospective study | August 1994 to February 1995 | 152 | Vertigo as a manifestation of stroke may not be an infrequent symptom |

|

Casani AP. et al., 2013 [26] Italy |

47 to 80 years old | Retrospective study | 2007 to 2011 | 11 | Pseudo-acute peripheral vertigo is not an uncommon diagnosis in otoneurological practice |

|

Doijiri R. et al., 2016 [27] Japan |

56 to 79 years old | Retrospective study | 2005 to 2015 | 221 |

In this study stroke was found in 11% of patients with isolated vertigo or dizziness attack. The posterior inferior cerebellar artery area is frequently implicated for isolated vertigo or dizziness |

|

Hesselbrock RR 2017 USA |

40 to 42 years old | Case reports | Not specified | 2 |

Accurate assessment of patients with acute vestibular symptoms can be challenging, Central causes of isolated acute vestibular symptoms are uncommon |

|

Perloff MD. et al., 2017 [28] USA |

Mean age 59.8 ± 16.7 | Retrospective study | January 2005 to January 2010 | 136 | There is an important proportion of cerebellar stroke among emergency department in patients with isolated dizziness |

|

Wang Y. et al., 2018 China |

Mean age 58.5 ± 12.3 for central vertigo and 52.1 ± 8.8 for peripheral vertigo | Retrospective study | January 2014 to July 2016 | 87 | Patients with isolated vertigo and three or more risk factors are at higher risk for central vertigo |

|

Lee H. et al., 2009 [29] Korea |

23 to 93 years old | Prospective study | January 2000 to July 2008 | 82 | Labyrinthine dysfunction of a vascular cause usually leads to combined loss of both auditory and vestibular functions |

|

Paul NL. et al., 2012 UK |

Mean age 75.9 ± 11.8 for carotid stroke and 73.3 ± 13.1 for vertebrobasilar stroke | Prospective study | April 2002 to March 2010 | 1141 | In patients with vertebrobasilar stroke, preceding transient isolated brainstem symptoms are common but rarely satisfy traditional definition of TIA |

|

Lee SU. et al., 2015 [30] Korea |

33 to 73 years old | Retrospective study | 2003 to 2014 | 18 | Presence of central vestibular signs allows bedside differentiation of isolated vestibular syndrome |

|

Parthasarathy R. et al., 2016 [31] Canada |

76 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 | Hypoperfusion to the flocculonodular lobe supplied by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery is likely a cause for intermittent vertigo |

|

Lee H. et al., 2002 [32] Korea |

17 to 74 years old | Prospective study | March 2000 to July 2001 | 72 | Migraine should be considered in the differential diagnosis of isolated recurrent vertigo of unknown cause |

|

Kim DD. et al., 2019 [33] Canada |

60 s years old | Case report | 2019 | 1 | Chronic naturopathic over- the-counter products intake may cause a subacute progressive cerebellar syndrome manifesting also with vertigo |

|

Adzic-Vukicevic T. et al., 2019 [34] Serbia |

66 years old | Case report | 2019 | 1 | Cryptococcosis may present even in immunocompetent patients and may show central nervous system involvement with vertigo |

|

Pula JH. et al., 2013 [35] USA |

19 to 55 years old | Prospective observational study | 1999 to 2011 | 7 | Multiple sclerosis is an uncommon cause of acute vestibular syndrome |

|

Kremer L. et al., 2014 [36] France, USA, UK, Japan, Canada, Germany |

Mean age 44.2 | Prospective observational study | Not specified | 258 | Brainstem involvement occurs in about one-third of patients with NMO and NMOSD; vertigo or vestibular ataxia occur in 1.7% of patients |

|

Lee JY. et al., 2019 [37], Korea |

20 to 80 years old | Retrospective analysis | January 2012 to January 2015 | 133 | Vestibular neuritis is characterized of rotational vertigo that last for over a day but the clinical course and the characteristics depends on the involvement site of the nerve |

|

Roberts RA., 2018 [38] USA |

60 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 | Patients using biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs could be at an increased risk for recurrent vestibular neuritis, with possible viral pathogenesis |

| Unal M. et al., 2006 [39] | 51 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 | It is important to consider Arnold-Chiari type I malformation in the differential diagnosis of adult vertigo cases |

| Spacey S.et al., 2003 | 2 to 32 years old | Review | Not specified | Not specified | Episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) is characterized by paroxysmal attacks of ataxia, vertigo, and nausea. Onset is typically in childhood or early adolescence |

| Rispoli MG. et al., 2019 [40] | 71 years old | Case report | March 2015 | 1 |

New missense mutation in the ATP1A2 gene is associated with atypical sporadic hemiplegic migraine, a disease possibly manifesting with vertigo |

| Di Stefano V. et al., 2020 [41] | 71 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 |

A rare case of atypical BHS due to compression of non-dominant vertebral artery with anatomical variants, resulting in stereotyped and reversible PICA syndrome |

| Potter BJ. et al., 2014 [42] | 90 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 |

A subclavian steal syndrome may occur when a significant stenosis in the subclavian artery compromises distal perfusion to the internal mammary artery, vertebral artery, or axillary artery |

| Jiang Y. et al., 2020 [43] | 34 years old | Case report | Not specified | 1 |

Frontal lobe epilepsy is a common neurological disorder with a broad spectrum of symptoms; it rarely presents with vertigo |

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of isolated neurological vertigo in childhood

| Differential Diagnosis | Incidence/Prevalence | Main Features | Clues for Differential | Examination Required | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalalgia | |||||

| Vestibular migraine |

24% Mainly > 5yo |

Vestibular symptoms (rotator vertigo) temporarily with migraine Time: 5 min or 72 h |

Episodic vertigo, age > 5yo, attacks lasting minutes to hours, association at least in some cases with migraine headache or migrainous phenomena | Physical exam and vestibular tests |

Lanzi et al. 1994 [12], D’Agostino et al. 1997 [1], Russell et al., 1999 Langhagen T et al. 2013 [14], Raucci et al. 2015 [7] |

| Benign Paroxysmal vertigo of childhood |

14 to 18% Mainly < 5yo F > M |

Episodic syndrome with short, non-epileptic, recurrent attacks of subjective or objective vertigo, which resolve spontaneously | Episodic vertigo, age < 5yo, attacks lasting seconds to minutes (to hours) without migraine headache | Clinical exam and instrumental investigations (absence of hearing impairment) |

D’Agostino et al. 1997 [1], Russell et al., 1999 [19] Langhagen T et al. 2013 [14], Raucci et al. 2015 [7] |

| Brain tumour and/or malformation | |||||

| Expansive endocranial pathologies and/or malformation | Rare | Vertigo, neurological symptoms, haedache | Association with additional neurologic deficits but neuroimaging is essential | Clinical exam and neuroimaging |

D’Agostino et al., 1997 [1] Caldarelli M. et al., 2007 [16] Raucci et al., 2015 [7] |

| Vascular diseases | |||||

| Neurovascular diseases | Rare | Vertigo, neurological symptoms, sincope | Association with additional neurologic deficits but neuroimaging is essential | Clinical exam and neuroimaging |

Kalashnikova et al.,2005 [17] Raucci et al., 2015 [7] |

| Demyelinating diseases | |||||

| Demyelinating diseases | Rare | Vertigo, multidirectional nystagmus | Association with additional neurologic deficits but neuroimaging is essential | Vestibular tests, MRI |

D’Agostino et al. 1997 [1], Raucci et al. 2015 [7], Salman M. et al., 2017 [13] |

| Inflammatory disease | |||||

| Vestibular neuritis |

16% Mainly > 5yo and adolescents |

Sudden onset of severe vertigo, sometimes associated with nausea and vomiting | Vertigo can be intensified by small changes in head position | Electronystagmography, thermal caloric testing |

D’Agostino et al., 1997 [1] Raucci et al., 2015 [7] |

| Others | |||||

| Somatoform vertigo |

2.5 to 16% Mainly adolescent girls |

Vertigo organically not sufficiently explained | Normal findings on physical exam and diagnostic evaluation | Psychiatric consultation |

D’Agostino et al., 1997 [1] Raucci et al., 2015 [7] |

| Head and/or cervical trauma | 7–10% of pediatric giddiness | Isolated vertigo or vertigo associated with hearing loss or others symptoms | History of previous trauma | Imaging of head/cervical chord | Raucci et al., 2015 [7] |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 3–9% of pediatric giddiness | Isolated vertigo or associated with autonomic symptoms, including syncope | Sudden drop in blood pressure after change in positioning | Blood pressure measurement, tilt test | Raucci et al., 2015 [7] |

| Vestibular paroxysmia | 4% of pediatric giddiness | Frequent episodes of vertigo, several times in a day, lasting for seconds to minutes, regardless of posture | Good response to carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine | Neuroimaging | Lehnen N et al., 2015 [20] |

| Iatrogenic form | Rare | Rarely cause of isolated vertigo | History of drug use or abuse | None/Urine analysis/toxicology screening | D’Agostino et al., 1997 [1] |

| Tuberous Sclerosis | Only report | Only one case described child with episodes of vertigo and headache | Presence of amartomas | Cranial MRI/abdomen ultrasound | Ramantani. et al. 2009 [15] |

| Familial episodic ataxia type II | Rare | Stress or exercise-induced vertigo and ataxia | Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, such as acetazolamide, produces a complete response to vertigo | Brain MRI | K. Mugundhan, 2011 [21] |

| Anisometropia and other ocular abnormalities | Rare | Sensory mismatch | Resolution with ophthalmological treatment | Ophthalmological examination | Bucci M.P. et al., 2004 [18] |

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis of isolated neurological vertigo in adulthood

| Differential Diagnosis | Incidence/Prevalence | Main Features | Clues for Differential | Examination Required | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary or secondary brain tumours | |||||

| Cerebellar lymphoma | CNS lymphoma represents 2–6% of all primary brain neoplasms (1.34 cases per million people); cerebellar involvement presents in only 9% of cases | Sudden onset of vertigo associated with vomiting |

Neurotological evaluation: atypical nystagmus patterns during diagnostic maneuvers may raise suspicion of central pathology |

Brain MRI with contrast enhancement and biopsy |

Joshi et al., 2020 [22] |

| Cerebellar metastases | 98,000–170,000 cases of brain metastases/year; metastases to the cerebellum accounts for 10–15% of all brain metastasis | Onset with severe headache, associated with nausea and vomiting, followed by positional vertigo and unsteady standing |

Neurotological evaluation: atypical nystagmus patterns during diagnostic maneuvers may raise suspicion of central pathology |

Brain MRI with contrast enhancement |

Joshi et al., 2020 [22] |

| Infratentorial gliomas | Incidence of glioma is about 6.0 per 100,000 person-years; infratentorial gliomas represent 4.6% of all gliomas |

Occasional attacks of vertigo and nausea lasting less than 30 seconds, related to changes in head position |

Neurotological evaluation: atypical nystagmus patterns during diagnostic maneuvers may raise suspicion of central pathology |

Brain MRI with contrast enhancement |

Joshi et al., 2020 [22] |

| Ischemic stroke | |||||

| Cerebellar stroke | 2–3% of 600,000 stroke-year in the United States. Presumed stroke etiologies: atherosclerotic occlusive lesions of the vertebral artery (32%), in situ branch artery disease (25%), cardioembolism (10%), vertebral artery dissection (5%) | Sudden onset of rotational vertigo associated with neurovegetative symptoms (nausea and vomiting). Sometimes concomitant headache or unilateral hearing loss | Head Impulse Test (HIT) is positive in acute peripheral vertigo (APV) and negative in cerebellar strokes (pseudo-APV). Delayed onset of other central symptoms/signs is not uncommon | CT scan, MRI and neurotologic examination | Grad A et al. 1989 [23], Norrving et al. 1995 [24]; Kim GW et al. 1996 [25], Casani et al., 2013 [26], Joshi et al., 2020 [22], Doijiri et al., 2016 [27], Hesselbrock, 2017; Perloff et al., 2017 [28], Wang et al., 2018; |

| Pons stroke | 7% of all ischemic strokes, 15–20% of posterior circulation ischemia. One in ten non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhages is located in the pons | Vertigo and vomiting, falls and pointing towards the affected side, direction fixed nystagmus towards the unaffected side | Impairment of smooth pursuit eye movements may be present | MRI and neurotologic examination | Norrving et al. 1995 [24]; Kim GW et al. 1996 [25], Lee et al. 2009; Doijiri et al., 2016 [27], Wang et al., 2018 |

| Medulla oblongata stroke |

Not found exact incidence/prevalence. In a study: annual incidence of posterior circulation infarction is 18 per 100 000 person years in an Australian study (Dewey et al. 2003) 10–20% of them may cause acute vestibular syndrome |

Diverse patterns of spontaneous nystagmus, gaze-evoked nystagmus and head-shaking nystagmus, possible otolithic dysfunction, subjective visual vertical (SVV) tilt, presence of at least one component of the ocular tilt reaction (OTR) | Less than a third of patients have abnormal ocular and cervical vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) in lateral medullary infarction. Abnormal VEMPs are seen in about one-half of patients in medial medullary infarction | MRI and neurotologic examination | Paul et al., 2013; Sun-Uk Lee et al., 2015; Doijiri et al., 2016 [27], Wang et al., 2018 |

| Persistent trigeminal artery (PTA) | Prevalence 0.1%-0.2% of cerebral angiograms | Isolated intermittent vertigo, followed by anterior and posterior circulation ischemic strokes symptoms | CT angiography evidence of PTA and CT signs of ischemic stroke | CT angiography | Parthasarathy, et al. 2016 [31] |

| Cephalalgia | |||||

| Migraine | *The prevalence of migraine according to IHS criteria was higher in the isolated recurrent vertigo group (61.1%) than in the control group (10%; p < 0.01) | isolated recurrent vertigo of unknown cause |

Extensive neurotological, including auditory and vestibular function testing and appropriate imaging studies |

ICHD3 criteria | Lee et al., 2002 [32] |

| Demyelinating disorders | |||||

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders (NMOSD) | The prevalence of MS in Europe is about 100–190/100.000 inhabitants; the prevalence range of NMOSD is ~ 0.5–4/100.000 worldwide | Isolated vertigo with or without nystagmus |

Extensive neurotological, including auditory and vestibular function testing and MRI |

Clinical exam, Brain MRI, HIT |

Pula et al., 2013 [35], Kremer et al., 2014 [36] |

| Infectious | |||||

| Neurocisticercosis | rare |

Positional vertigo nystagmus |

Cultural tests |

Clinical exam, Brain MRI |

Joshi et al., 2020 [22] |

| Cryptococcosis | rare | Fever, vertigo | Cultural tests |

Clinical exama, Laboratory tests (CSF culture) neuroimaging (CT, MRI) |

Adzic-Vukicevic et al., 2019[34] |

| Others | |||||

| Vestibular neuritis | Unknown | Acute onset of vertigo with repetitive falls without hearing loss or tinnitus | recent viral infection | Serology for herpes virus | Lee JY et al., 2019 [37], Roberts RA et al., 2018 [38] |

| Arnold-Chiari malformation | Rare | Displacement of the cerebellar tonsils | Neuroradiology | Brain MRI | Unal M et al., 2006 [39] |

| Episodic ataxia type 2 | Rare | Paroxysmal recurrent attacks of vertigo which usually respond to the treatment with potassium channel blockers and acetazolamide | autosomal dominant | Genetics | Spacey S et al., 1993 [44] |

| Hemiplegic migraine | Rare | Acute attack with isolated vertigo or more often associated with hemiparesis and confusion | Clinical exam, genetic testing | Rispoli et al., 2019 [40] | |

| Bowhunter’s syndrome and | Very rare | Recurrent attacks of vertigo associated with neck rotation | Neuroradiology | Dynamic MRI and neurosonology | Di Stefano et al., 2020 [41] |

| Subclavian steal syndrome | Rare | Recurrent attacks of vertigo associated with the use of an arm | Neuroradiology | MRI and neurosonology | Potter et al., 2014 [42] |

| Cerebellar syndrome due to naturopathic over-the-counter supplements | Only a single report | Vertigo, gait unsteadiness, nystagmus, hypermetric saccades, dysmetria, ataxia | Anamnesis of supplement use |

Clinical exam, Laboratory tests, Neuroimaging |

Kim DD et al., 2019 [33] |

| Frontal lobe epilepsy | Rare | Seizures with onset from the frontal lobe | Antiepileptics (i.e., sodium valproate, levetiracetam, and lamotrigine) | EEG | Jiang et al., 2020 [43] |

The most common cause of isolated vertigo in pediatric population is VM, followed by benign paroxysmal vertigo in childhood (BPVC) [7, 14]. Neurovascular diseases, tumors and demyelinating diseases can rarely provoke an altered perception of position in the environment in childhood [7, 16]. More frequent causes of vertigo are orthostatic hypotension, vestibular neuritis (VN) and vestibular paroxysmia [7, 20]. Lastly, a miscellany of conditions causing isolated vertigo are described in children, such as head trauma, drugs, genetic diseases, visual diseases and mental disorders [1, 7, 15, 18, 21, 45].

Conversely, in adulthood, isolated vertigo usually represents the first symptom of an acute vascular disease or a brain tumor [22, 25, 27, 31]. Other possible etiologies are demyelinating disorders, VM and VN [32, 36, 37, 46, 47]. Lastly, isolated vertigo in adults can be associated with genetic disorders, malformations, vascular diseases or psychological illness [22, 33, 34, 39, 42, 48, 49].

Discussion

Our systematic review revealed that vertigo is a common symptom and an indicator of several diseases in childhood and adulthood. When associated with other symptoms, it is easy to distinguish among differentials. Conversely, when the patient shows isolated vertigo, the diagnostic approach becomes more complex and only through an accurate anamnesis, a complete physical examination and specific tests the clinician can achieve the correct diagnosis. Causes of vertigo in childhood present an age-dependent distribution which may be helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. For example, children under five years of age are usually diagnosed with BPVC (71%), followed by VM (19%). These two entities represent the most common causes of vertigo in children under 10 years of age as well, even if with different prevalence (each representing approximately 30% of cases). On the contrary, adolescents are most commonly diagnosed with VM [50]. Also in adulthood causes of vertigo are differently distributed according to age. For example, older patients have a higher burden of vertigo due to cerebrovascular diseases [51]. On the contrary, younger patients more commonly suffer from vertigo due to VM or multiple sclerosis (MS) [35, 52]. The aim of this review is to provide an illustrative overview of isolated neurological vertigo and to design a useful tool for the differential diagnosis of vertigo in the ED.

It needs to be highlighted that bias can arise at all stages of the review process. Hence, we have made more than an effort to minimize the risk of bias in this review identifying possible concerns with the review process. We tried to follow the ROBIS tool for the assessment of bias in the systematic review. Study eligible criteria have been pre-defined to find relevant literature on vertigo to develop an algorithm. The selection of a single database and English language might have limited the search strategy and this may represent a possible source of bias. However, the search strategy was carried out by two authors (NP and VD) independently, with the second reviewer checking the decisions of the first reviewer. Bias may also have arisen from the process of data extraction which is, by its nature, subjective and open to interpretation. Hence, extraction of data was performed by all the author involved working together to develop the algorithm. We calculated an overall level risk of bias as “low-moderate”, according to the ROBIS tool [53].

Isolated neurological vertigo in childhood

Vertigo in pediatric age is a challenge due to different etiopathologies, the short-lived manifestations owing to rapid compensation, the inability of children to describe the experienced symptoms and the feasibility of diagnostic tests [5].

In childhood, the most common causes of isolated neurological vertigo are VM and BPVC, although frequencies vary between different studies [6, 12, 19]. In opposition to adulthood, cerebral vascular diseases, brain tumors and demyelinating disorders are uncommon causes [4, 6, 7, 54]. Differential diagnosis include also orthostatic hypotension, VN and vestibular paroxysmia [1, 20, 55]. Finally genetic diseases, head trauma, drugs, visual and psychiatric disorders should be taken into account while evaluating a child with isolated vertigo [1, 7, 15, 18, 21, 45].

In this systematic review we proposed an algorithm to facilitate the approach to children presenting to the ED with isolated vertigo, based primarily on a detailed history and a careful examination.

Vestibular migraine

VM is the most common cause of vertigo in children, accounting for 24% of all vertigo causes and is more frequently observed in adolescents [6]. It is characterized by a range of signs and vestibular manifestations temporally associated with migraine [56]. However, presentation may be variable and the onset of vertigo can precede the development of the headache by many years [57].

Patients typically present with episodic attacks of spontaneous or positional vertigo that can last between 5 min and 72 h and can be associated with headache, photophobia and phonophobia [6, 57]. The combination of vestibular manifestations and headache is commonly observed, but less than 50% have both symptoms in every attack. During the acute attack, patients can develop pathological nystagmus, meanwhile between the attacks the neurological examination is usually normal. In contrast to headache, vertigo does not respond well to triptans or non-steroid analgesics [58]. Finally there are no specific biomarkers and the diagnosis relies mainly on the patient medical history [57].

Benign paroxysmal vertigo in childhood

BPVC is an episodic syndrome with short (seconds to minutes) recurrent attacks of subjective or objective vertigo, which resolves spontaneously. BPVC is a common cause of vertigo in childhood and it precedes the onset of migraine in over 35% of children by many years [4, 7, 59]. A family history of migraine is present in half of patients [59]. Children under the age of five and females are mainly affected. BPVC needs to be distinguished from Panayiotopoulos syndrome, a benign epileptic syndrome that can present also with vertigo and it is characterized by repetitive nature and association with autonomic symptoms [45]. Clinical exam and instrumental investigations are normal with no hearing impairment [14, 59].

Neurovascular diseases

Arteriovenous malformations presenting with vertigo symptoms are more frequent in the pediatric population (35%) than in adults (6%) and symptoms are related to the compression of the vestibular nerve or the brainstem nuclei [4]. Among neurovascular disorders, posterior circulation stroke represents approximately 3% of children with vertigo, usually secondary to cervico-cerebral artery dissection [60]. Other vascular diseases responsible for central vertigo are represented by cerebellar infarction, hemorrhage, occlusion of the basilar artery and dissection of the vertebral artery. Among these causes, Wallenberg's syndrome, also known as lateral medullary infarction, causes vertigo [17, 54]. Moreover vasculitis associated with rheumatologic disorders such as Wegener’s granulomatosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis could cause vertigo related to impaired vertebrobasilar circulation [61]. Indeed Moya-Moya disease, characterized by stenosis of the intracranial carotid arteries and basal collateral arteries, can be associated with vertigo on standing [62]. In these cases, a full physical examination usually helps to find out other associated neurologic deficits.

Tumors

Brain tumors are not a common cause of vertigo in children. Tumors of the posterior cranial fossa rarely begin with vertigo in the pediatric population (< 1%). More commonly they present with headache, vestibular symptoms or additional neurological deficits due to the compression or involvement of the nearby nuclei and fiber tracts [6, 7, 63]. Although rare, medulloblastoma and other cerebellar tumors have been reported to cause vertigo in children [6, 7].

Demyelinating diseases

Vertigo, usually lasting days or weeks, has been reported as initial sign of MS in 20–50% of patients [54]. The acute manifestation of vertigo in MS falls into two categories: acute vestibular syndrome as central form and BPPV as peripheral form [35]. It is then necessary an adequate differential diagnosis, that can be difficult in MS with atypical central signs [13, 35]. Cochleo-vestibular dysfunction with vertigo have been described also in chronic-inflammatory-demyelinating neuropathy [64].

Orthostatic hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension determines vertigo in 3–9% of symptomatic children. Affected children become symptomatic within 3 min of moving from posture to sitting or standing from a supine position. It can occur as isolated symptom or associated with autonomic dysfunctions [6]. It is fundamental to exclude life-threatening cardiac origin and to assess blood pressure also to rule out hypertension, which can in turn cause vertigo [7].

Vestibular neuritis

VN represents between 1 and 16% of cases of pediatric vertigo and it is commonly founded in children older than five years of age and adolescents [65]. It is an acute inflammation of the vestibular component of the eighth cranial nerve that primarily occurs after an acute upper-respiratory viral infection, mainly due to herpes simplex, but also to Adenoviruses and Enteroviruses [6]. Affected children present with a sudden onset of severe vertigo without hearing loss that lasts for few days or weeks and resolves in a one-month period. It can be often intensified by small changes in head position and can be associated with nausea and vomiting [65]. On examination the clinician can elicit a horizontal-rotary spontaneous nystagmus with quick phases to the unaffected side but the neurological exam can be completely normal at the time of presentation. Diagnosis is made by electronystagmography and thermal caloric testing [65].

Vestibular paroxysmia

Though rare, vestibular paroxysmia can cause multiple short episodes of rotatory or to-and-fro vertigo, up to 30 times or more in a day, that last from seconds to minutes [20]. In some patients, attacks are unprovoked but sometimes head movements or hyperventilation can elicit them [66]. Imaging may demonstrate the neurovascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve at the root entry zone and to rule out brain tumors [6, 66]. Distinctive findings include hyperventilation-induced nystagmus and mild vestibular impairment on caloric testing, as well as the good response to carbamazepine [6, 20].

Genetic diseases

Familial episodic ataxia type II is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by vertigo that lasts for minutes to hours and ataxia, typically triggered by sport, stress and alcohol [21]. This disease is due to a mutation in the CACNA1A-gene, coding for a subunit of the P/Q calcium channel, and it has its onset in childhood or adolescence. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor produces a complete response to vertigo [21]. Similar episodes have been reported in patients affected by hemiplegic migraine, especially from ATP1A2 mutations [40, 41, 67].

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by hamartic development in several organs, most notably brain, heart, kidneys, lungs and skin. To date, only one case report described a 9-year-old patient with episodes of vertigo and headache followed by full spontaneous recovery as initial symptom of tuberous sclerosis [15].

Other causes of vertigo

Head trauma from falls and whiplash injury are possible cause of vertigo among children, owing to the labyrinthine concussion or the development of perilymphatic fistula [6, 7]. Children affected by post-traumatic vertigo tend to exhibit abnormal results to vestibular tests in nearly half of the cases. Neuroimaging is mandatory to detect possible fractures or brain lesions [2, 6].

Despite a large number of drugs including vertigo as a possible side effect, iatrogenic forms are rarely reported in children [1].

Anisometropia [6] and other binocular vision disorders, including vergence abnormality [18] are other possible causes of vertigo due to sensory mismatch; ophthalmological evaluation and treatment are mandatory.

Finally, the differential diagnosis of childhood vertigo comprises somatoform vertigo, commonly found in adolescent girls that usually present with isolated episodic or chronic vertigo with normal findings on physical examination [14]. A careful clinical work-up to rule out potential diseases and a psychiatric consultation are essential [6].

Isolated neurological vertigo in adulthood

In adulthood, vertigo can occur as a result of conditions related to impaired cerebral circulation, especially of the vertebrobasilar district [23] or it can be the first sign of intra-axial and extra-axial brain tumors, particularly of primary tumors of the posterior cranial fossa and cerebellar metastases [22, 68]. Isolated vertigo is also associated with migraine [56] and neuro-immunological diseases [47]. Lastly, there are rare genetic diseases [44], malformation syndromes [39] and vascular disorders [42, 69] whose clinical manifestation, at the onset, can be represented by vertigo. To date, there are few data on functional pathological vertigo, which remains a diagnosis of exclusion [49].

As per children, we proposed a diagnostic algorithm to guide clinician’s approach to adults with isolated neurological vertigo in ED.

Ischemic stroke

Acute isolated vertigo can frequently occur in patients suffering from stroke in the distribution of the vertebrobasilar circulation [23]. The frequency of isolated vertigo in stroke ranges from 11 to 29% but it is probably underestimated [28].

Differentiating isolated vascular vertigo from other disorders involving the inner ear is difficult, especially when AICA territory, that supplies both peripheral and central vestibular structures, is involved [29]. Patients can develop typical BPPV as a consequence of labyrinthine ischemia [23], which cannot be detected with current imaging techniques [70]. The most salient feature which distinguishes central positional vertigo (CPV) from BPPV is atypical direction of nystagmus for the stimulated canal during repositioning maneuvers [71] that usually shows an initial peak and a subsequent decrescendo pattern [72].

Vertigo can be the only presenting symptom in patients with posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) infarction [26] and it is considered rare in superior cerebellar artery (SCA) infarction, which does not have significant vestibular connections [73].

Isolated vertigo can result from dorsal medullary infarction, which can involve vestibular nuclei, nucleus prepositus hypoglossi or inferior cerebellar peduncle [30]. Clinical signs of acute peripheral vestibulopathy have been reported in patients with pontine lesions, as a consequence of vertebrobasilar ischemia [74].

Isolated intermittent vertigo can be rarely the consequence of hypoperfusion of the flocculo-nodular lobe due to a persistent trigeminal artery (PTA) or posterior circulation stroke in the context of a PTA [31]. Finally, an isolated vestibular-like syndrome (VLS) has been recently reported in patients with ischemic strokes confined to the insula [75].

Almost all the patients with vascular vertigo show central vestibular signs, such as gaze-evoked nystagmus, normal or contralesional head-impulse test (HIT), skew deviation and central patterns of spontaneous nystagmus [30]. Head-Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew (HINTS) is a three-step examination method which has 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity for stroke [11].

Tumors

Brain tumors account for approximately 2% of all cancers [76]. Even if most patients manifest with a large variety of neurological symptoms, few may present just with vertigo at the onset [22], particularly tumors of posterior fossa [77]. However, an accurate examination may often show additional nystagmus with central features (see above). The most frequent neoplastic diseases at this site are cerebellar metastases (intra-axial) and vestibular schwannoma (extra-axial). Primary intra-axial posterior fossa tumors may involve cerebellum, brainstem or the fourth ventricle [68]. Among extra-axial ones a meningioma may also cause isolated vertigo [78]. Furthermore, it is worth to mention a non-neoplastic mass effect lesion which may frequently cause vertigo constituted by arachnoidal cyst sited in the posterior fossa [79].

Migraine

Migraine should always be considered among the causes of isolated neurological vertigo because vertigo may be one of the symptoms preceding or manifesting during migraine attack [80]. Furthermore, in the last International Classification of Headache Disorders there is even a definite condition called “vestibular migraine” that may reveal itself as intermittent episodes of vertigo [56].

Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating disorders

Unexpected diagnoses of MS have been made in patients who had an isolated positional vertigo as the only symptom [81]. Responsible lesions are often in the intra-pontine eighth nerve fascicle and oculomotor signs can be associated [35]. In these cases, neuro-otological examination might show a normal HIT with suppression of transient evoked otoacoustic emission [81]. Brain MRI, as well as oligoclonal IgG bands in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should be recommended, especially in young women with isolated positional vertigo and a normal HIT [35].

Even neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) can rarely present with isolated vertigo, especially early in the disease course [36]. Vertigo and nystagmus can precede typical manifestations of neuritis optica and myelitis, as a consequence of lesions in the medulla, cerebellum or pons [46]. Therefore search for antiacquaporin-4 antibodies and anti-myelin oligodendrocyte antibodies should be taken into consideration in selected cases [35]

Vestibular neuritis

VN is a condition caused by inflammation of the vestibular nerve commonly seen in middle-aged adults [47] as consequence of a viral infection (frequently related to herpes zoster virus). In VN, there is an acute onset of isolated vertigo without hearing loss or tinnitus but sometimes patients present with repetitive falls. Vertigo is severe, lasting for 2–3 days and is usually followed by gradual recovery in few weeks; symptoms and diagnostic test can change in relation to nerve’s involvement site [37, 82]. This condition should be suspected in patients who presented a recent viral infection, especially when taking immunosuppressive drugs [38].

Rare causes

Arnold-Chiari malformation is a rare condition in which a displacement of the cerebellar tonsils can affect functions controlled by the cerebellum and brainstem thus causing vertigo[39].

Episodic ataxia type 2 is a rare condition, allelic with hemiplegic migraine and spinocerebellar ataxia, caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in the CACNA1A gene resulting in the dysfunction of voltage-dependent calcium channels [41]. The onset is in fifth-seventh decade and patients suffer from paroxysmal recurrent attacks of vertigo which usually respond to potassium channel blockers and acetazolamide [44].

Repetitive vascular compressions in vertebral arteries (bowhunter’s syndrome) [69] or atherosclerosis in subclavian artery (subclavian steal syndrome) [42] are both conditions in which recurrent attacks of vertigo occur owing to an impaired vascular flow in posterior circulation [69]. However, even if vertigo can be the only reported complaint, there are usually associated neurological signs such as nystagmus, gaze palsy, pupillary defects or sensory-motor deficits [69]. Rarely, in adult age, vertigo has been reported in frontal lobe epilepsy as the sole ictal symptom at the seizure onset, or, more frequently, followed by other ictal signs/symptoms [43]. Finally, functional isolated vertigo has been rarely reported [49].

Conclusions

Our systematic review demonstrates that isolated neurological vertigo could be due to different causes in childhood and adulthood. VM and BPVC are the most frequent disorders in children suffering from isolated vertigo presenting the ED; meanwhile the same symptom in adults is more frequently related to impaired distribution of the vertebrobasilar circulation, especially in the older ages. Age may be helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. In the majority of the cases, an appropriate diagnosis can be established thorough a careful history collection and a complete clinical examination, as illustrated in the algorithms proposed in the paper that could be an important tool for a prompt differential diagnosis. Indeed it is crucial to be aware of those differentials for pediatric and adult age to be able to make the proper diagnosis and manage those patients appropriately.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency Department

- VM

Vestibular migraine

- BPVC

Benign paroxysmal vertigo in childhood

- VN

Vestibular neuritis

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- BPPV

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

- AICA

Anterior inferior cerebellar artery

- CPV

Central positional vertigo

- PICA

Posterior inferior cerebellar artery

- SCA

Superior cerebellar artery

- PTA

Persistent trigeminal artery

- VLS

Vestibular-like syndrome

- HIT

Head-impulse test

- HINTS

Head-Impulse Nystagmus Test of Skew

- NMOSD

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: NP, VDS, ER, AG, MGR, AT, AL, FB, UR, PP. Data acquisition and analysis: NP, VDS, ER, AG, MGR, AT, AL, FB, UR, PP. Draft of the text: NP, VDS, ER, AG, MGR, AT, AL, FB, UR, PP. Draft of the figures: NP, VDS, AL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No study funders to report.

Availability of data and materials

All data used and/or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.D’Agostino R, Tarantino V, Melagrana A, Taborelli G. Otoneurologic evaluation of child vertigo. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;40:133–139. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(97)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacGregor DL. Vertigo. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23:10–16. doi: 10.1542/pir.23.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisdorff A, Von Brevern M, Lempert T, Newman-Toker DE. Classification of vestibular symptoms: Towards an international classification of vestibular disorders. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat. 2009;19:1–13. doi: 10.3233/VES-2009-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruber M, Cohen-Kerem R, Kaminer M, Shupak A. Vertigo in children and adolescents: Characteristics and outcome. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:109624. doi: 10.1100/2012/109624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pietro CA, Dallan I, Navari E, Sellari Franceschini S, Cerchiai N. Vertigo in childhood: proposal for a diagnostic algorithm based upon clinical experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35:180–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devaraja K. Vertigo in children; a narrative review of the various causes and their management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;111:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raucci U, Vanacore N, Paolino MC, Silenzi R, Mariani R, Urbano A, Reale A, Villa MP, Parisi P. Vertigo/dizziness in pediatric emergency department: Five years’ experience. Cephalalgia. 2015;36:593–598. doi: 10.1177/0333102415606078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwergal A, Dieterich M. Vertigo and dizziness in the emergency room. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33:117–125. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edlow JA, Newman-Toker D. Using the Physical Examination to Diagnose Patients with Acute Dizziness and Vertigo. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:617–628. doi: 10.1016/J.JEMERMED.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggers SDZ. Approach to the Examination and Classification of Nystagmus. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2019;43:S20–S26. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: Three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40:3504–3510. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanzi G, Balottin U, Borgatti R. A Prospective Study of Juvenile Migraine With Aura. Headache J Head Face Pain. 1994;34:275–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3405275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salman MS, Klassen SF, Johnston JL. Recurrent Ataxia in Children and Adolescents. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44:375–383. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langhagen T, Schroeder A, Rettinger N, Borggraefe I, Jahn K. Migraine-Related Vertigo and Somatoform Vertigo Frequently Occur in Children and Are Often Associated. Neuropediatrics. 2013;44:055–058. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramantani G, Niggemann P, Hahn G, Näke A, Fahsold R, Lee-Kirsch AM. Unusual radiological presentation of tuberous sclerosis complex with leptomeningeal angiomatosis associated with a hypomorphic mutation in the TSC2 gene. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:333–337. doi: 10.1177/0883073808323021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldarelli M, Novegno F, Massimi L, Romani R, Tamburrini G, Di Rocco C. The role of limited posterior fossa craniectomy in the surgical treatment of Chiari malformation Type I: Experience with a pediatric series. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:187–195. doi: 10.3171/ped.2007.106.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalashnikova LA, Zueva YV, Pugacheva OV, Korsakova NK. Cognitive impairments in cerebellar infarcts. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2005;35:773–779. doi: 10.1007/s11055-005-0123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucci MP, Kapoula Z, Yang Q, Wiener-Vacher S, Brémond-Gignac D. Abnormality of vergence latency in children with vertigo. J Neurol. 2004;251:204–213. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell G, Abu-Arafeh I. Paroxysmal vertigo in children-an epidemiological study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49 Suppl 1:S105–7. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehnen N, Langhagen T, Heinen F, Huppert D, Brandt T, Jahn K. Vestibular paroxysmia in children: a treatable cause of short vertigo attacks. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57:393–396. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mugundhan K, Thiruvarutchelvan K, Sivakumar S. Familial episodic ataxia type II. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:666–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi P, Mossman S, Luis L, Luxon LM. Central mimics of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an illustrative case series. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-04101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grad A, Baloh RW. Vertigo of vascular origin. Clinical and electronystagmographic features in 84 cases. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:281–284. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520390047014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norrving B, Magnusson M, Holtås S. Isolated acute vertigo in the elderly; vestibular or vascular disease? Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91(1):43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb05841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim GW, Heo JH. Vertigo of Cerebrovascular Origin Proven by CT Scan or MRI: Pitfalls in clinical differentiation from vertigo of aural origin. Yonsei Med J. 1996;37:47–51. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1996.37.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casani AP, Dallan I, Cerchiai N, Lenzi R, Cosottini M, Sellari-Franceschini S. Cerebellar infarctions mimicking acute peripheral vertigo: How to avoid misdiagnosis? Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg (United States) 2013;148:475–481. doi: 10.1177/0194599812472614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doijiri R, Uno H, Miyashita K, Ihara M, Nagatsuka K. How Commonly Is Stroke Found in Patients with Isolated Vertigo or Dizziness Attack? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:2549–2552. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perloff MD, Patel NS, Kase CS, Oza AU, Voetsch B, Romero JR. Cerebellar stroke presenting with isolated dizziness: Brain MRI in 136 patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:1724–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H, Kim JS, Chung EJ, Yi HA, Chung IS, Lee SR, Shin JY. Infarction in the territory of anterior inferior cerebellar artery: Spectrum of audiovestibular loss. Stroke. 2009;40:3745–3751. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.564682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SU, Park SH, Park JJ, Kim HJ, Han MK, Bae HJ, Kim JS. Dorsal Medullary Infarction: Distinct Syndrome of Isolated Central Vestibulopathy. Stroke. 2015;46:3081–3087. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parthasarathy R, Derksen C, Saqqur M, Khan K. Isolated intermittent vertigo: A presenting feature of persistent trigeminal artery. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016;7:161–163. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.165430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H, Sohn S, Jung DK, Cho YW, Lim JG, Yi SD, Yi HA. Migraine and isolated recurrent vertigo of unknown cause. Neurol Res. 2002;24:663–665. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim DD, Shoesmith C, Ang LC. Toxic diffuse isolated cerebellar edema from over-the-counter health supplements. Neurology. 2019;92:965–966. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adzic-Vukicevic T, Cevik M, Poluga J, Micic J, Rubino S, Paglietti B, Barac A. An exceptional case report of disseminated cryptococcosis in a hitherto immunocompetent patient. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2020;62:e3. doi: 10.1590/s1678-9946202062003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pula JH, Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC. Multiple sclerosis as a cause of the acute vestibular syndrome. J Neurol. 2013;260:1649–1654. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6850-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kremer L, Mealy M, Jacob A, Nakashima I, Cabre P, Bigi S, Paul F, Jarius S, Aktas O, Elsone L, Mutch K, Levy M, Takai Y, Collongues N, Banwell B, Fujihara K, De Seze J. Brainstem manifestations in neuromyelitis optica: A multicenter study of 258 patients. Mult Scler J. 2014;20:843–847. doi: 10.1177/1352458513507822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JY, Park JS, Kim MB. Clinical Characteristics of Acute Vestibular Neuritis According to Involvement Site. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40:797–805. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts RA. Management of recurrent vestibular neuritis in a patient treated for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Audiol. 2018;27:19–24. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-17-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unal M, Bagdatoglu C. Arnold-Chiari type I malformation presenting as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in an adult patient. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:296–298. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106003082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rispoli MG, Di Stefano V, Mantuano E, De Angelis MV. Novel missense mutation in the ATP1A2 gene associated with atypical sporapedic hemiplegic migraine. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(10):e231129. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Stefano V, Rispoli MG, Pellegrino N, Graziosi A, Rotondo E, Napoli C, Pietrobon D, Brighina F, Parisi P (2020) Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of hemiplegic migraine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry jnnp-2020–322850 . 10.1136/jnnp-2020-322850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Potter BJ, Pinto DS. Subclavian Steal Syndrome. Circulation. 2014;129:2320–2323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang Y, Zhou X. Frontal lobe epilepsy manifesting as vertigo: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(9):300060520946166. doi: 10.1177/0300060520946166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spacey S. Episodic Ataxia Type 2. GeneReview: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graziosi A, Pellegrino N, Di Stefano V, Raucci U, Luchetti A, Parisi P. Misdiagnosis and pitfalls in Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;98(Pt A):124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim W, Kim S-H, Lee SH, Li XF, Kim HJ. Brain abnormalities as an initial manifestation of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1107–1112. doi: 10.1177/1352458511404917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le TN, Westerberg BD, Lea J. Vestibular neuritis: Recent advances in etiology, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;82:87–92. doi: 10.1159/000490275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornelius JF, George B, Oka DND, Spiriev T, Steiger HJ, Hänggi D. Bow-hunter’s syndrome caused by dynamic vertebral artery stenosis at the cranio-cervical junction-a management algorithm based on a systematic review and a clinical series. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stone J. Functional neurological disorders: The neurological assessment as treatment. Pract Neurol. 2016;16:7–17. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee JD, Kim CH, Hong SM, Kim SH, Suh MW, Kim MB, Shim DB, Chu H, Lee NH, Kim M, Hong SK, Seo JH. Prevalence of vestibular and balance disorders in children and adolescents according to age: A multi-center study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;94:36–39. doi: 10.1016/J.IJPORL.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Navi BB, Kamel H, Shah MP, Grossman AW, Wong C, Poisson SN, Whetstone WD, Josephson SA, Johnston SC, Kim AS. Rate and predictors of serious neurologic causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1080–1088. doi: 10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Formeister EJ, Rizk HG, Kohn MA, Sharon JD. The Epidemiology of Vestibular Migraine: A Population-based Survey Study. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39:1037–1044. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, Davies P, Kleijnen J, Churchill R. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–234. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLINEPI.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan Y. Differential diagnosis of dizziness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:200–203. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32832b2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raucci U, Della VN, Ossella C, Paolino MC, Villa MP, Reale A, Parisi P. Management of childhood headache in the emergency department. Review of the literature Front Neurol. 2019;10:886. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olesen J. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dieterich M, Obermann M, Celebisoy N. Vestibular migraine: the most frequent entity of episodic vertigo. J Neurol. 2016;263:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7905-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jahn K. Vertigo and balance in children - Diagnostic approach and insights from imaging. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15(4):289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lagman-Bartolome AM, Lay C. Pediatric Migraine Variants: a Review of Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Curr Neurol Neurosci. Rep. 2015;15(6):34. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0551-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simonnet H, Deiva K, Bellesme C, Cabasson S, Husson B, Toulgoat F, Théaudin M, Ducreux D, Tardieu M, Saliou G. Extracranial vertebral artery dissection in children: natural history and management. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:729–738. doi: 10.1007/s00234-015-1520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Worden BF, Blevins NH. Pediatric vestibulopathy and pseudovestibulopathy: Differential diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15:304–309. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282bf139e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uchino H, Kazumata K, Ito M, Nakayama N, Houkin K. Novel insights into symptomatology of moyamoya disease in pediatric patients: Survey of symptoms suggestive of orthostatic intolerance. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;20:485–488. doi: 10.3171/2017.5.PEDS17198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spennato P, Nicosia G, Quaglietta L, Donofrio V, Mirone G, Di Martino G, Guadagno E, del Basso de Caro ML, Cascone D, Cinalli G, Posterior fossa tumors in infants and neonates. Child’s Nerv Syst. 2015;31:1751–1772. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2783-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blanquet M, Petersen JA, Palla A, Veraguth D, Weber KP, Straumann D, Tarnutzer AA, Jung HH. Vestibulo-cochlear function in inflammatory neuropathies. Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;129:863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brodsky JR, Cusick BA, Zhou G. Vestibular neuritis in children and adolescents: Clinical features and recovery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;83:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jahn K, Langhagen T, Schroeder AS, Heinen F. Vertigo and dizziness in childhood update on diagnosis and treatment. Neuropediatrics. 2011;42:129–134. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedrich T, Tavraz NN, Junghans C. ATP1A2 mutations in migraine: Seeing through the facets of an ion pump onto the neurobiology of disease. Front Physiol. 2016;7:239. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shih RY, Smirniotopoulos JG. Posterior Fossa Tumors in Adult Patients. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2016;26:493–510. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Stefano V, Colasurdo M, Onofrj M, Caulo M, De Angelis MV. Recurrent stereotyped TIAs: atypical Bow Hunter’s syndrome due to compression of non-dominant vertebral artery terminating in PICA. Neurol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim JS, Cho KH, Lee H. Isolated labyrinthine infarction as a harbinger of anterior inferior cerebellar artery territory infarction with normal diffusion-weighted brain MRI. J Neurol Sci. 2009;278:82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Macdonald NK, Kaski D, Saman Y, Sulaiman AAS, Anwer A, Bamiou DE. Central positional nystagmus: A systematic literature review. Front Neurol. 2017;8:141. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi JY, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Glasauer S, Kim JS. Central paroxysmal positional nystagmus: Characteristics and possible mechanisms. Neurology. 2015;84:2238–2246. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amarenco P, Roullet E, Hommel M, Chaine P, Marteau R. Infarction in the territory of the medial branch of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:731–735. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.9.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thömke F, Hopf HC. Pontine lesions mimicking acute peripheral vestibulopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:340–349. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Di Stefano V, De Angelis MV, Montemitro C, Russo M, Carrarini C, di Giannantonio M, Brighina F, Onofrj M, Werring DJ, Simister R. Clinical presentation of strokes confined to the insula: a systematic review of literature. Neurol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Rouse C, Chen Y, Dowling J, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan J (2014) CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol 16:iv1–iv63 . 10.1093/neuonc/nou223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Lee HJ, Kim ES, Kim M, Chu H, Il MH, Lee JS, Koo JW, Kim HJ, Hong SK. Isolated horizontal positional nystagmus from a posterior fossa lesion. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:905–910. doi: 10.1002/ana.24292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi SJ, Bin LJ, Bae JH, Yoon JH, Lee HJ, Kim CH, Park K, Choung YH. A posterior petrous meningioma with recurrent vertigo. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;5:234–236. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2012.5.4.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tunes C, Flønes I, Helland C, Goplen F, Wester KG. Disequilibrium in patients with posterior fossa arachnoid cysts. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132:23–30. doi: 10.1111/ane.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iljazi A, Ashina H, Lipton RB, Chaudhry B, Al-Khazali HM, Naples JG, Schytz HW, Vukovic Cvetkovic V, Burstein R, Ashina S. Dizziness and vertigo during the prodromal phase and headache phase of migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2020;40:1095–1103. doi: 10.1177/0333102420921855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Veros K, Blioskas S, Karapanayiotides T, Psillas G, Markou K, Tsaligopoulos M. Clinically isolated syndrome manifested as acute vestibular syndrome: Bedside neuro-otological examination and suppression of transient evoked otoacoustic emissions in the differential diagnosis. Am J Otolaryngol - Head Neck Med Surg. 2014;35:683–686. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsang BKT, Chen ASK, Paine M. Acute evaluation of the acute vestibular syndrome: differentiating posterior circulation stroke from acute peripheral vestibulopathies. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1352–1360. doi: 10.1111/imj.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used and/or analysed during this study are included in this published article.