Abstract

Background

It is crucial to maintain periodontal health in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Biotype is a critical factor to be considered in this regard. This systematic review investigated the scientific evidence on the relationship between gingival biotype and marginal periodontal alterations induced by orthodontic interventions.

Methods

An electronic search was conducted for pertinent studies in three databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane up to August 1, 2019 based on a detailed protocol according to the PRISMA statement. The authors also completed a hand search in six dental journals and the bibliographic lists of the relevant studies.

Results

Of 1512 citations retrieved through the electronic search, 602 were duplicate entries. By evaluating titles, abstracts, and full texts, eight articles conformed to the inclusion criteria; however, no relevant studies were found through hand searching. The evidence suggested that recession was inversely related with the thickness of the facial margin. These findings were more evident in proclined teeth and patients using fixed appliances.

Conclusion

The existing evidence suggests that orthodontic therapy might result in mild detrimental effects on the periodontium, especially in patients with thin biotype. However, due to the limited investigations and their inconsistent methodology, further well-designed prospective studies are necessary.

Keywords: Gingival biotype, gingival recession, gingival thickness, orthodontics

Introduction

Malocclusion is the third most prevalent oral health problem worldwide. 1,2 Orthodontic treatments facilitate oral hygiene measures and establish occlusal stability and lip competency by eliminating traumatic occlusion and crowding; thus, some investigators have considered these interventions as potential means to improve periodontal health. 3,4 However, orthodontic appliances might increase plaque accumulation and impede proper oral hygiene, which raise the possibility of making these treatments detrimental to periodontal tissues. 5-9

Lindhe and Seibert 10 used the term “periodontal biotype” to describe morphologic characteristics of the periodontium. In general, there are two types of gingival biotype: “thin scalloped” and “thick flat.” 11,12 The biotype depends on many factors, including age, sex, genetic factors, as well as the shape, position, and size of the teeth. 13 In addition, the width and thickness of the facial gingiva vary from one individual to another, and even in different regions of a mouth. Therefore, there are diverse “gingival phenotypes,” a term used by Muller and Eger 14 for the first time. Studies have shown that gingival thickness plays a fundamental role in mucogingival problems. As the attachment level is minimal in thin biotype, it is more prone to trauma and inflammation. 15-17 Consequently, accurate pre-orthodontic evaluation of the biotype has been recommended in order to preclude potential complications. 17-19

Given the increasing demand for orthodontic treatments and the importance of maintaining periodontal health, the nature and extent of the complications related to these interventions in patients with different biotypes should be taken into account. Despite the conflicting opinions about the relationship between orthodontic treatments and periodontal health, few studies have addressed the orthodontic-related changes affecting marginal periodontal tissues. This study investigated the scientific evidence on the relationship between gingival biotype and periodontal changes caused by orthodontic movements.

Methods

Protocol

A detailed protocol was developed and followed, according to the PRISMA statement. 20,21

Search strategy

The eligibility criteria were as follows:

-Study design: We evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective, retrospective, and cross-sectional studies.

-Population: We included only studies on humans, with no restrictions in terms of patient’s age or occlusion characteristics, although we did exclude studies that included patients with severe periodontal diseases or craniofacial anomalies.

-Intervention: We focused on studies assessing fixed or removable orthodontic appliances, or both. Since orthognathic surgery and distraction osteogenesis might have different consequences compared to nonsurgical orthodontic therapy, we agreed to exclude studies comprising these procedures.

-Comparison: We assessed periodontal outcomes in patients with different types of gingival biotype, who underwent orthodontic treatment.

-Types of outcome measures: Owing to the heterogeneity of endpoints in periodontal studies, 22 we could formulate no single periodontal outcome measure. Instead, we included all studies with at least one type of periodontal parameter.

Search methods

Two authors (RA and AM) extracted articles through an electronic search and a hand search of the specific journals. The reference lists of the selected full-text articles were also screened for the unidentified or unpublished relevant studies.

-Electronic search: PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library (including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL] and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [CDSR]) were searched up to August 1, 2019. We did not limit our search strategy regarding the study design, as doing so could have excluded some pertinent publications. 23 No publication status and language or time restrictions were applied.

Search terms included the following keywords and were modified appropriately for each database.

Search #1: Orthodontic* AND (“gingival biotype” OR “periodontal biotype” OR “gingival thickness”)

Search #2: Orthodontic* AND (“gingival recession” OR “gingival side effect” OR “periodontal side effect” OR mucogingival)

Hand search: Five journals, American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Angle Orthodontist, Journal of Periodontology, Journal of Dental Research and Journal of Clinical Periodontology, were hand-searched for studies reporting on the periodontal effects of orthodontic treatment in patients with different types of gingival biotype.

The titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles were screened independently by two authors (RA and AM) to assess the fulfillment of the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles were obtained in case the supplementary data were needed. Any disagreements during the process were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

Two of the reviewers (RA and MK) independently assessed the quality of the identified studies and resolved any disagreements through discussion.

For cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, which consists of eight items: four items regarding selection, one item regarding the comparability of the groups, and three items regarding the outcome assessment. 24 Then, we classified the bias status as low (all quality items met), moderate (one or two quality items not met), or high (three or more criteria not met).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Four reviewers (STD, MS, ADS, and MAS) independently extracted the relevant data by using a predefined data extraction table to report on the study design, participants, orthodontic intervention, periodontal outcomes, and the gingival biotype.

Results

Search results

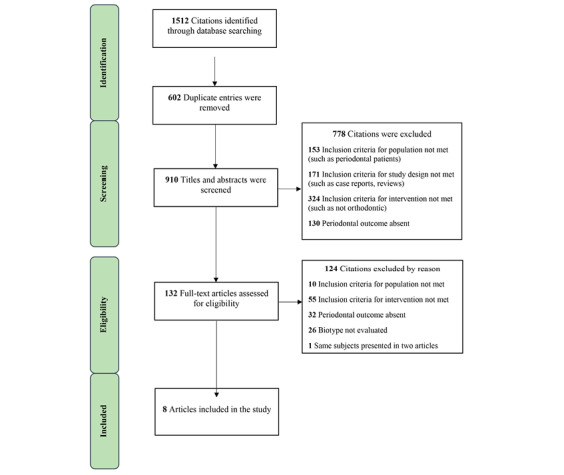

Of the 1512 citations retrieved through the electronic search, 602 were duplicate entries. Eight articles were eligible to be included in the study through evaluation of the titles, abstracts, and full texts (Figure 1). We found no studies that met the inclusion criteria through the hand searching of the literature. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 1. The characteristics of the included studies .

| Characteristic | Study | |||||||

| Ji et al (28) | Stappert et al (27) | Rasperini et al (16) | Boke et al (8) | Yared et al (25) | Szarmach et al (30) | Melsen, Allias (29) | Ngan et al (26) | |

| Study Design | Retrospective | Prospective | Prospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Cross-sectional | Retrospective | Retrospective |

| Participants |

403 (285 F, 118 M) |

29 |

16 (6 F, 10 M) |

251 (177 F, 74 M) |

34 |

18 (11 F, 7 M) |

150 (114 F, 36 M) |

20 (12 F, 8 M) |

| Age | 11–43 |

≤13 14–18 ≥19 |

Mean age: 21±8.20 | 8-17.8 (mean 13.37 ± 2.06) | 18-33 | 12-39 |

F: 22-65 M: 23-50 |

11-16 |

| Biotype determination | Probing transparency | Transgingival probing |

Biotype probe (Hu-Friedy) |

Intra-oral photographs, Visual inspection of the gingival texture and capillary transparency |

Scaled digital caliper, |

Periodontal probe |

Intra-oral photographs, Visual inspection of the gingival texture and capillary transparency |

Visual inspection |

| Biotype classification |

Thin Thick |

Thin (≤2.5mm) Thick (>2.5mm) |

Thin Medium Thick Very thick |

Thin Thick |

<0.5 mm ≥0.5 mm |

Thin gingiva and the root bone layer |

Thin Thick |

Thin Moderate Thick |

| Intervention | NM | Fixed appliance with premolar extraction | Fixed appliance |

58 Fixed appliance with extraction 173 Fixed appliance without extraction 20 Functional appliance |

Fixed appliance | Fixed appliance | Fixed appliance without extraction | NM |

| Periodontal Outcome |

GI, PI, GR, and plaque index |

Gingival cleft | PPD, GR, CAL, KTW, FMBS | GR, Plaque, Inflammation | Plaque index, GI, PPD, CAL, GR | GR | GR, Plaque, Inflammation | GR, Inflammation |

| Quality assessment* | *** | **** | ****** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** |

F = Female, M = Male, GI = Gingival Index, PI = Periodontal Index, GR = Gingival Recession, PPD = Probing Pocket Depth, CAL = Clinical Attachment Level, KTW = Keratinized Tissue Width, FMBS = Full-mouth Bleeding Score

NM = not mentioned

*Number of the stars represents quality of the study based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

The participants were 8–65 years of age, with the majority undergoing orthodontic treatment as adolescents or young adults. They had various forms of malocclusion. Three studies 25-27 did not report the malocclusion status. One study restricted the inclusion criteria to those who had infraversion or open bite, 28 and one study included only subjects with Class I and Class II malocclusion. 29 The types of orthodontic treatments were fixed appliances, 8,16,25,29,30 fixed appliances with premolar extraction, 8,27 functional appliances, 8 or not reported. 26,28

The selected articles reported various markers of periodontal status as follows: gingival recession, 8,16,25,26,28-30 probing pocket depth, 16,25 clinical attachment level, 16,25 inflammation, 8,16,25,26,28,29 periodontal index, 28 plaque index, 8,25,28,29 and keratinized tissue width. 16,25 One study reported gingival clefts, 27 but none of them reported on tooth loss, tooth mobility, or other adverse effects. In addition, Szarmach et al 30 evaluated crowding, protrusion, improper frenal attachment, and the depth of the oral vestibule.

Regarding gingival biotype determination, Rasperini et al, 16 Melsen and Allais, 29 and Ngan et al 26 used the four mandibular incisors, while Yared et al 25 evaluated the mandibular central incisors.

The results of these investigations indicated that some periodontal complications, such as increased probing depth, attachment loss, and gingival recession might be more prevalent in orthodontic patients; five studies 16,25,28-30 reported that recession was inversely related with the width of keratinized gingiva and gingival thickness. Rasperini et al16 demonstrated that the thin biotype and incisor proclination could induce gingival recession (0.17 mm) and reduce the width of keratinized gingiva (-0.67 mm), which was not evident in the alignment and retroclination movements. However, only one of their patients showed a gingival recession of 1.5 mm on a mandibular left central incisor. Their study also revealed no significant relationship between the biotype and changes in probing depth and attachment loss.

Boke et al 8 reported that in patients treated with fixed appliances, the mean values of visible plaque, visible inflammation, and gingival recession were 2.93±6.78, 2.76±6.20, and 0.11±0.40 before treatment, respectively. These parameters increased significantly after orthodontic treatment and reached 5.92±9.08, 17.75±18.74, and 0.48±1.13, respectively; however, such a relationship was not evident for functional appliances. The canines were the most affected teeth by gingival recession (9.48% for maxillary and 7.76% for mandibular canines in the extraction group; 4.04% for maxillary and 3.76% for mandibular cuspids in the non-extraction group).

Szarmach et al 30 reported that cases with thin gingival margin and thin buccal bone had more recession, which was evident more frequently in skeletal class III patients. Melsen and Allais 29 demonstrated that only 2.8% of the subjects developed recession >2 mm, and 5% of the pre-existing gingival recessions improved. They concluded the baseline recession, width of keratinized gingiva, gingival biotype, and gingival inflammation were correlated with gingival recession.

Discussion

Orthodontic appliances might damage periodontal tissues by creating retentive areas for dental plaque; even with excellent oral hygiene, the appliances cause a change in the intraoral microflora, leading to a bacterial array similar to that present in sites affected by periodontal disease. 31

In contrast to patients with thick gingiva, those with a thin-scalloped biotype are considered at risk; therefore, identification of these high-risk subjects is warranted. The evidence identified by this systematic review suggested that there might be an association between the gingival biotype and orthodontic treatment-induced periodontal complications. 16,25,27-30 However, there are some limitations, including a limited number of studies, potential of bias, inconsistent methods for biotype determination, and various orthodontic interventions, making the comparison of the results difficult.

An issue that might provoke debate is the inconsistent and inaccurate methods used for biotype determination, including visual inspection and indirect measurements on dental casts or intraoral photographs. Usually, simple visual inspection is used in clinical practice and even in research to identify the gingival biotype. However, the accuracy of this method has never been documented. Egbhali et al 32 reported that by using visual evaluation for gingival thickness, the biotype was accurately identified in about half of the cases, regardless of the clinician’s experience. As a result, other methods, such as direct measurements,33 gingival transparency, 34 ultrasonic devices, 37 and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) 35 have been proposed.

Several studies have addressed the effects of different therapeutic methods on periodontal complications; gingival recession has been the main periodontal adverse outcome evaluated. Although this problem is not often attributable to the type of orthodontic appliance, 36,37 there is debate in this regard. Some investigations have indicated that fixed appliances are associated with inflammation and even gingival recession, 38-41 while some others have demonstrated no detrimental effects induced by the long-term presence of these appliances. 6,42 However, it should be noted that these controversies might be due to the complex etiology of gingival recession, in which orthodontic appliances and fixed retainers are only two contributing factors. 43-47 For example, thin soft tissues are more prone to the detrimental effects of environmental factors, such as plaque, calculus, and gingivitis; 13,17,48-50 tooth position and alveolar bone anatomy might also play a role. 51 In addition, there is insufficient evidence on some orthodontic parameters, such as force magnitude, location, and type of movement, which might result in dehiscence and gingival recession. 52

Similar to biotype, different methods have been used to evaluate gingival recession. The measurement of the gingival recession on dental casts 29,53 could be misleading due to factors, such as extrusion, crown fracture, attrition, or restoration. 54,55 Crown length measurement for indirect estimation of gingival recession 8 is also not reliable, as the tooth length might be affected by different factors, such as gingival hyperplasia.

Although some studies have demonstrated no significant association between malocclusion and biotype, 2,13,56 some others have reported minimal gingival thickness in mandibular central and lateral incisors in class III patients. 5,30,57 The periodontal tissue response has frequently been evaluated in class II patients, while it might be different in individuals with class III malocclusion. Six studies included in this review described the Angle classification for their participants, but only one 30 clearly addressed the correlation between gingival biotype and the type of malocclusion.

One of the questions this review aimed to answer was the necessity of periodontal intervention for orthodontic patients with different gingival biotypes. As excessive labial inclination might lead to dehiscence and gingival recession on the labial surface, 47,59-61 patients whose teeth are being moved labially (>95 degrees) should be informed about the risk of gingival recession. 17,58,62,63 Therefore, bodily movement of the lower incisors should be preferred 2,64 and exercised with caution in patients with thin gingival biotype and keratinized gingiva <2 mm. 11 It has been indicated that as long as the orthodontic movements are confined to the alveolar process, the risk of periodontal lesions would be minimal. 50,65-69

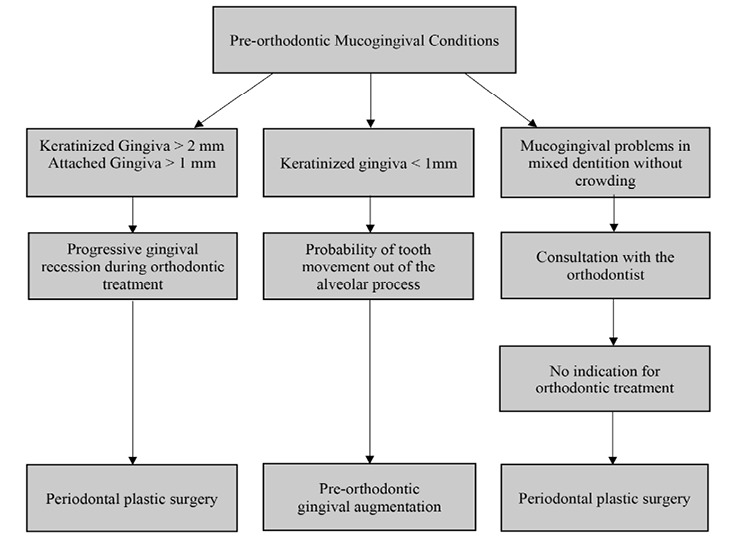

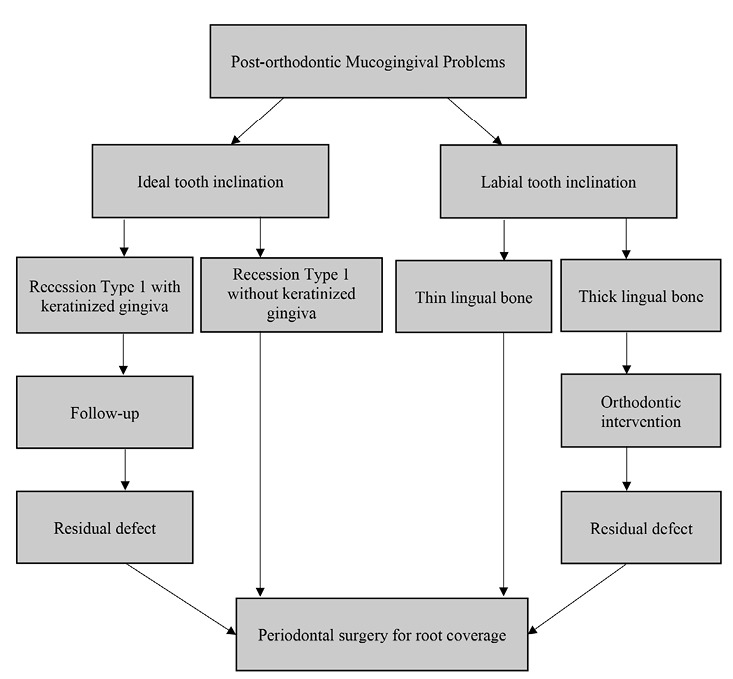

The width of the keratinized tissue plays a significant role in the decision-making process. It seems that periodontal intervention is rational in case of progressive recession or tooth movement out of the alveolar process (Figure 2). It should be noted that the recession (<2 mm) reported in some studies is usually not progressive and might be related to the heterogeneity of tissue quality. 55,70-72 If gingival recession is observed after the orthodontic therapy, the treatment alternatives depend on its severity 73 and the probability of elimination by orthodontic intervention (Figure 3). It should also be kept in mind that the clinical relevance of the induced recession is unclear, and most studies have only documented the pre- or post-orthodontic incidence of gingival recession. 7,36,60,74,75

Figure 2.

The management of pre-orthodontic treatment mucogingival problems.

Figure 3.

The management of post-orthodontic treatment mucogingival problems.

The strengths of this systematic review include the comprehensive search of the relevant literature, no restriction on the language or study design, and the quality assessment of the included studies.

Conclusions

The existing evidence suggests that orthodontic treatment might result in small detrimental effects on the periodontium, especially in patients with thin gingival biotype. However, the available data do not make it possible to determine whether adverse periodontal changes are indicative of site-specific changes, host-specific factors, a direct consequence of the orthodontic forces, or study bias. It seems that due to the limited investigations and their inconsistent methodology, further well-designed prospective studies are necessary.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict(s) of interest related to the publication of this work.

Authors’ Contributions

Design of the work: RA; acquisition of data: STD, MS, ADS, and MAS; analysis of data: RA, and AM; interpretation of data: RA, and MK; drafting the work: AM; revision: MK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding.

References

- 1.Gusmão ES, de Queiroz RDC, Coelho RS, Cimões R, dos Santos RL. Association between malpositioned teeth and periodontal disease. Dental press journal of orthodontics. 2011;16(4):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staufer K, Landmesser H. Effects of crowding in the lower anterior segment--a risk evaluation depending upon the degree of crowding. Organ/official journal Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kieferorthopadie. 2004;65(1):Organ/official journal Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kieferorthopadie 2004;65(1). doi: 10.1007/s00056-004-0207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma K, Mangat S, Kichorchandra MS, Handa A, Bindhumadhav S, Meena M. Correlation of Orthodontic Treatment by Fixed or Myofunctional Appliances and Periodontitis: A Retrospective Study. The journal of contemporary dental practice. 2017;18(4):322–5. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bock NC, Saffar M, Hudel H, Evälahti M, Heikinheimo K, Rice DPC. et al. Long-term effects of Class II orthodontic treatment on oral health. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics. 2018;79(2):96–108. doi: 10.1007/s00056-018-0125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaya Y, Alkan Ö, Keskin S. An evaluation of the gingival biotype and the width of keratinized gingiva in the mandibular anterior region of individuals with different dental malocclusion groups and levels of crowding. Korean journal of orthodontics. 2017;47(3):176–85. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2017.47.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juloski J, Glisic B, Vandevska-Radunovic V. Long-term influence of fixed lingual retainers on the development of gingival recession: A retrospective, longitudinal cohort study. The Angle orthodontist. 2017;87(5):658–64. doi: 10.2319/012217-58.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciavarella D, Tepedino M, Gallo C, Montaruli G, Zhurakivska K, Coppola L. et al. Post-orthodontic position of lower incisors and gingival recession: A retrospective study. Journal of clinical and experimental dentistry. 2017;9(12):e1425–e30. doi: 10.4317/jced.54261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boke F, Gazioglu C, Akkaya S, Akkaya M. Relationship between orthodontic treatment and gingival health: A retrospective study. European journal of dentistry. 2014;8(3):373–80. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.137651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polson AM, Subtelny JD, Meitner SW, Poison AP, Sommers EW, Iker HP. et al. Long-term periodontal status after orthodontic treatment. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1988;93(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seibert J LJ. Esthetics and periodontal therapy. Textbook of clinical periodontology. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1989. p. 477-514.

- 11.Rossell J, Puigdollers A, Girabent-Farrés M. A simple method for measuring thickness of gingiva and labial bone of mandibular incisors. Quintessence international. 2015;46(3):265–71. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a32919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta P, Peng LL. The width of the attached gingiva-Much ado about nothing? Journal of dentistry. 2010;38(7):517–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zawawi KH, Al-Harthi SM, Al-Zahrani MS. Prevalence of gingival biotype and its relationship to dental malocclusion. Saudi medical journal. 2012;33(6):671–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller HP ET. Gingival phenotypes in young male adults. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1997;24:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mazurova K, Kopp JB, Renkema AM, Pandis N, Katsaros C, Fudalej PS. Gingival recession in mandibular incisors and symphysis morphology-a retrospective cohort study. European journal of orthodontics. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Rasperini G, Acunzo R, Cannalire P, Farronato G. Influence of Periodontal Biotype on Root Surface Exposure During Orthodontic Treatment: A Preliminary Study. The International journal of periodontics & restorative dentistry. 2015;35(5):665–75. doi: 10.11607/prd.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zawawi KH, Al-Zahrani MS. Gingival biotype in relation to incisors› inclination and position. Saudi medical journal. 2014;35(11):1378–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyrebek B, Orzechowska A, Cudzilo D, Plakwicz P. Evaluation of changes in the width of gingiva in children and youth Review of literature. Developmental period medicine. 2015;19(2):212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennström JL, Lindhe J, Sinclair F, Thilander B. Some periodontal tissue reactions to orthodontic tooth movement in monkeys. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1987;14(3):121–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hujoel PP, DeRouen TA. A survey of endpoint characteristics in periodontal clinical trials published 1988-1992, and implications for future studies. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1995;22(5):397–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harden A, Peersman G, Oliver S, Mauthner M, Oakley A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of health promotion interventions in the workplace. Occupational medicine (Oxford, England) 1999;49(8):540–8. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.8.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wells G, Brodsky L, O›Connell D, Shea B, Henry D, Mayank S, et al. XI Cochrane Colloquium: Evidence, Health Care and Culture. Barcelona, Spain; 2003. Evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS): an assessment tool for evaluating the quality of non-randomized studies. http://www.citeulike.org/user/SRCMethodsLibrary/article/12919189.

- 25.Yared KFG, Zenobio EG, Pacheco W. Periodontal status of mandibular central incisors after orthodontic proclination in adults. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2006;130(1):6.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngan PW, Burch JG, Wei SHY. Grafted and ungrafted labial gingival recession in pediatric orthodontic patients: Effeets of retraction and inflammation. Quintessence international. 1991;22(2):103–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stappert D, Geiman R, Zadi ZH, Reynolds MA. Gingival clefts revisited: Evaluation of the characteristics that make one more susceptible to gingival clefts. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2018;154(5):677–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji JJ, Li XD, Fan Q, Liu XJ, Yao S, Zhou Z. et al. Prevalence of gingival recession after orthodontic treatment of infraversion and open bite. Journal of orofacial orthopedics = Fortschritte der Kieferorthopadie : Organ/official journal Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kieferorthopadie. 2019;80(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00056-018-0159-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melsen B, Allais D. Factors of importance for the development of dehiscences during labial movement of mandibular incisors: a retrospective study of adult orthodontic patients. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2005;127(5):552–61; quiz 625. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szarmach IJ, Wawrzyn-Sobczak K, Kaczyńska J, Kozłowska M, Stokowska W. Recession occurrence in patients treated with fixed appliances--preliminary report. Advances in medical sciences. 2006;51 Suppl 1:213–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reichert C, Hagner M, Jepsen S, Jager A. Interfaces between orthodontic and periodontal treatment: their current status. Organ/official journal Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kieferorthopadie. 2011;72(3):Organ/official journal Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Kieferorthopadie 2011;72(3). doi: 10.1007/s00056-011-0023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eghbali A, De Rouck T, De Bruyn H, Cosyn J. The gingival biotype assessed by experienced and inexperienced clinicians. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2009;36(11):958–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenberg J, Laster L, Listgarten MA. Transgingival probing as a potential estimator of alveolar bone level. Journal of periodontology. 1976;47(9):514–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.9.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kan JY, Rungcharassaeng K, Umezu K, Kois JC. Dimensions of peri-implant mucosa: an evaluation of maxillary anterior single implants in humans. Journal of periodontology. 2003;74(4):557–62. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikiforidou M, Tsalikis L, Angelopoulos C, Menexes G, Vouros I, Konstantinides A. Classification of periodontal biotypes with the use of CBCT A cross-sectional study. Clinical oral investigations. 2016;20(8):2061–71. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aziz T, Flores-Mir C. A systematic review of the association between appliance-induced labial movement of mandibular incisors and gingival recession. Australian orthodontic journal. 2011;27(1):33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruf S, Hansen K, Pancherz H. Does orthodontic proclination of lower incisors in children and adolescents cause gingival recession? American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 1998;114(1):100–6. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rody WJ, Jr Jr. , Elmaraghy S, McNeight AM, Chamberlain CA, Antal D, Dolce C, et al. Effects of different orthodontic retention protocols on the periodontal health of mandibular incisors. 2016;19(4):198–208. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renkema AM, Fudalej PS, Renkema AAP, Abbas F, Bronkhorst E, Katsaros C. Gingival labial recessions in orthodontically treated and untreated individuals: A case - Control study. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2013;40(6):631–7. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levin L, Samorodnitzky-Naveh GR, Machtei EE. The association of orthodontic treatment and fixed retainers with gingival health. Journal of periodontology. 2008;79(11):2087–92. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandis N, Vlahopoulos K, Madianos P, Eliades T. Long-term periodontal status of patients with mandibular lingual fixed retention. European journal of orthodontics [Internet] 2007;29(5):471–6. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renkema AM, Fudalej PS, Renkema A, Kiekens R, Katsaros C. Development of labial gingival recessions in orthodontically treated patients. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2013;143(2):206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciok E, Górski B, Dylewski Ł, Sobieska E, Zadurska M. Relationship between gingival recessions and orthodontic treatment-Review of literature. Journal of Stomatology. 2015;68(5):566–78. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slutzkey S, Levin L. Gingival recession in young adults: occurrence, severity, and relationship to past orthodontic treatment and oral piercing. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2008;134(5):652–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Closs LQ, Grehs B, Raveli DB, Rösing CK. Occurrence, extension, and severity of gingival margin alterations after orthodontic treatment. World journal of orthodontics. 2008;9(3):e1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gebistorf M, Mijuskovic M, Pandis N, Fudalej PS, Katsaros C. Gingival recession in orthodontic patients 10 to 15 years posttreatment: A retrospective cohort study. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2018;153(5):645–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allais D, Melsen B. Does labial movement of lower incisors influence the level of the gingival margin? A case-control study of adult orthodontic patients. European journal of orthodontics. 2003;25(4):343–52. doi: 10.1093/ejo/25.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghassemian M, Lajolo C, Semeraro V, Giuliani M, Verdugo F, Pirronti T. et al. Relationship Between Biotype and Bone Morphology in the Lower Anterior Mandible: An Observational Study. Journal of periodontology. 2016;87(6):680–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.150546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geiger AM. Mucogingival problems and the movement of mandibular incisors: A clinical review. American journal of orthodontics. 1980;78(5):511–27. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(80)90302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maynard Jr JG, Ochsenbein C. Mucogingival problems, prevalence and therapy in children. Journal of periodontology. 1975;46(9):543–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.1975.46.9.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bollen AM, Cunha-Cruz J, Bakko DW, Huang GJ, Hujoel PP. The effects of orthodontic therapy on periodontal health: a systematic review of controlled evidence. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2008;139(4):413–22. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi YJ, Chung CJ, Kim KH. Periodontal consequences of mandibular incisor proclination during presurgical orthodontic treatment in Class III malocclusion patients. The Angle orthodontist. 2015;85(3):427–33. doi: 10.2319/021414-110.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lo Russo L, Zhurakivska K, Montaruli G, Salamini A, Gallo C, Troiano G. et al. Effects of crown movement on periodontal biotype: a digital analysis. Odontology. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10266-018-0370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Handelman CS, Eltink AP, BeGole E. Quantitative measures of gingival recession and the influence of gender, race, and attrition. Progress in orthodontics. 2018;19(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s40510-017-0199-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flores-Mir C. Does orthodontic treatment lead to gingival recession? Evidence-based dentistry. 2011;12(1):20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alkan O, Kaya Y. Assessment of Gingival Biotype and Keratinized Gingival Width of Maxillary Anterior Region in Individuals with Different Types of Malocclusion. 2018;31(1):13–20. doi: 10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2018.17028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maroso FB, Gaio EJ, Rösing CK, Fernandes MI. Correlation between gingival thickness and gingival recession in humans. Acta odontologica latinoamericana : AOL. 2015;28(2):162–6. doi: 10.1590/S1852-48342015000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Danz JC, Bibby BM, Katsaros C, Stavropoulos A. Effects of facial tooth movement on the periodontium in rats: a comparison between conventional and low force. 2016;43(3):229–37. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McComb J. Orthodontic treatment and isolated gingival recession: a review. British journal of orthodontics. 1994;21(2):151–9. doi: 10.1179/bjo.21.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morris JW, Campbell PM, Tadlock LP, Boley J, Buschang PH. Prevalence of gingival recession after orthodontic tooth movements. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2017;151(5):851–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richman C. Is gingival recession a consequence of an orthodontic tooth size and/or tooth position discrepancy? «A paradigm shift». Compendium of continuing education in dentistry. 2011;32(1):62–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joss-Vassalli I, Grebenstein C, Topouzelis N, Sculean A, Katsaros C. Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession: a systematic review. Orthodontics & craniofacial research. 2010;13(3):127–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2010.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farronato G, Giannini L, Galbiati G, Maspero C. A 5-year longitudinal study of survival rate and periodontal parameter changes at sites of dilacerated maxillary central incisors. Progress in orthodontics. 2014;15:3. doi: 10.1186/2196-1042-15-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahn HW, Lee DY, Park YG, Kim SH, Chung KR, Nelson G. Accelerated decompensation of mandibular incisors in surgical skeletal class III patients by using augmented corticotomy: a preliminary study. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2012;142(2):199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andlin-Sobocki A, Marcusson A, Persson M. 3-year observations on gingival recession in mandibular incisors in children. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1991;18(3):155–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wennström JL. Mucogingival considerations in orthodontic treatment. Seminars in orthodontics. 1996;2(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(96)80039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moriarty JD. Mucogingival considerations for the orthodontic patient. Curr Opin Periodontol. 1996;3:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boyd RL. Mucogingival considerations and their relationship to orthodontics. Journal of periodontology. 1978;49(2):67–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johal A, Katsaros C, Kiliardis S, Leito P, Rosa M, Sculean A. et al. State of the science on controversial topics: Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession (a report of the Angle Society of Europe 2013 meeting) Progress in orthodontics. 2013;14(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/2196-1042-14-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Consolaro A. Occlusal trauma can not be compared to orthodontic movement or Occlusal trauma in orthodontic practice and V-shaped recession. Dental press journal of orthodontics. 2012;17(6):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Closs LQ, Branco P, Rizzatto SD, Raveli DB, Rosing CK. Gingival margin alterations and the pre-orthodontic treatment amount of keratinized gingiva. Brazilian oral research. 2007;21(1):58–63. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242007000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lafzi A, Abolfazli N, Eskandari A. Assessment of the etiologic factors of gingival recession in a group of patients in northwest iran. Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects. 2009;3(3):90–3. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2009.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller PD, Jr Jr. A classification of marginal tissue recession. The International journal of periodontics & restorative dentistry. 1985;5(2):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Renkema AM, Fudalej PS, Renkema A, Bronkhorst E, Katsaros C. Gingival recessions and the change of inclination of mandibular incisors during orthodontic treatment. European journal of orthodontics. 2013;35(2):249–55. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjs045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Renkema AM, Navratilova Z, Mazurova K, Katsaros C, Fudalej PS. Gingival labial recessions and the post-treatment proclination of mandibular incisors. European journal of orthodontics. 2015;37(5):508–13. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]