Abstract

Three genes with homology to glycosyl hydrolases were detected on a DNA fragment cloned from a psychrophilic lactic acid bacterium isolate, Carnobacterium piscicola strain BA. A 2.2-kb region corresponding to an α-galactosidase gene, agaA, was followed by two genes in the same orientation, bgaB, encoding a 2-kb β-galactosidase, and bgaC, encoding a structurally distinct 1.76-kb β-galactosidase. This gene arrangement had not been observed in other lactic acid bacteria, including Lactococcus lactis, for which the genome sequence is known. To determine if these sequences encoded enzymes with α- and β-galactosidase activities, we subcloned the genes and examined the enzyme properties. The α-galactosidase, AgaA, hydrolyzes para-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside and has optimal activity at 32 to 37°C. The β-galactosidase, BgaC, has an optimal activity at 40°C and a half-life of 15 min at 45°C. The regulation of these enzymes was tested in C. piscicola strain BA and activity on both α- and β-galactoside substrates decreased for cells grown with added glucose or lactose. Instead, an increase in activity on a phosphorylated β-galactoside substrate was found for the cells supplemented with lactose, suggesting that a phospho-galactosidase functions during lactose utilization. Thus, the two β-galactosidases may act synergistically with the α-galactosidase to degrade other polysaccharides available in the environment.

Glycosyl hydrolases (EC 3.2.1 to 3.2.3) cleave the glycosidic bond(s) between two or more carbohydrates or the bond between a carbohydrate moiety and a noncarbohydrate moiety. Traditionally, glycosyl hydrolases were grouped together based on substrate specificity. For example, all β-galactosidases were combined into one group (EC 3.2.1.23) because of their shared ability to hydrolyze lactose. However, classification based on substrate specificity is complicated by the fact that some enzymes hydrolyze more than one substrate. Some glycosyl hydrolases have activity on both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated substrates (3, 21) or on β-glucosides and β-galactosides (2) and some β-galactosidases have activity on β-fucosides and β-galacturonides (11, 15, 25).

The increase in the number of sequenced glycosyl hydrolases and the availability of new analytical methods has permitted the reorganization of these enzymes into families based on amino acid sequence similarities and hydrophobic cluster analysis (12, 13, 14). There are presently four families containing enzymes with β-galactosidase activity, families 1, 2, 35, and 42, and three families which contain enzymes with α-galactosidase activity, families 4, 27, and 36. New glycosyl hydrolases which have been sequenced can be grouped into a specific family on the basis of DNA or deduced amino acid similarity. In many cases, however, there is no information to verify the substrate specificity of the enzymes within these groups or their possible role(s) in cellular metabolism.

The glycosyl hydrolases found in lactic acid bacteria have been of special interest because of their importance to the dairy and food processing industries. In contrast to most other bacteria, nearly all lactic acid bacteria transport and utilize lactose via the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system, which requires the concomitant activity of a phospho-β-galactosidase. β-Galactosidases belonging to a different family, and sharing sequence similarity with the well-characterized Escherichia coli lacZ-encoded enzyme, have also been detected in lactic acid bacteria such as Streptococcus thermophilus or Lactococcus lactis (7).

The genus Carnobacterium is a recent taxonomic addition to the lactic acid bacteria group (4, 5). Most Carnobacterium species were isolated from meat or fish (1, 23) and are similar to those in the Lactobacillus genus but do not grow on acetate and have a higher tolerance to oxygen and high pH (24). Research on Carnobacterium species has centered on their ability to produce bacteriocins (8, 19). Recently, during our investigation of psychrophilic organisms, we isolated from soil a new Carnobacterium piscicola strain, BA, which hydrolyzed the β-galactosidase chromogenic substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) at 4°C. Initial work discovered a gene, bgaB, encoding a family 42 glycosyl hydrolase that had a temperature optimum of 30°C (6). This was the first report of a gene from this family in any lactic acid bacterium.

Additional sequencing of this cloned fragment suggested that the bgaB gene is centered between two regions with homology to other glycosyl hydrolases. The gene agaA is located in the region adjacent to the N-terminal end of bgaB, and shared sequence homology with a group of α-galactosidases characterized from other bacteria and some eukaryotes, including a sequence from the lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum. Adjacent to the C-terminal end of the bgaB β-galactosidase gene was a second, unrelated β-galactosidase gene, bgaC. Genes similar to bgaC have not been reported in the lactic acid bacteria. This includes L. lactis, for which the sequence of the entire genome is known.

In order to explore the functions encoded by these two new putative genes, they were subcloned and their ability to produce enzymes with α- and β-galactosidase activities was tested. The arrangement of these genes on a single fragment suggested that they might function together to degrade saccharides containing both alpha and beta linkages rather than being involved in lactose hydrolysis. We examined the regulation of these enzymes in the native C. piscicola strain BA and found that their activities decreased when the medium was supplemented with either glucose or lactose. In contrast, a phospho-galactosidase activity increased during growth with lactose. These results suggest that a phospho-galactosidase is responsible for lactose utilization and that the unusual cluster of glycosyl hydrolase genes reported here might be involved in the degradation of other polysaccharides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids with individual genes.

Subclones were created for both the α-galactosidase, designated agaA, and the β-galactosidase, or bgaC, genes. Construct BA-a1 carrying the α-galactosidase gene was created by digesting plasmid DNA from the original transformant at native NaeI and PstI (Promega, Madison, Wis.) restriction sites, followed by gel purification of the DNA fragment (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.), ligation into the pΔα vector (26) (Epicentre Fast Link ligase; Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.), and transformation into E. coli DH5α cells. Insert DNA prepared from the resulting DH5α subclones (Wizard kit; Promega) was verified through restriction analysis (Promega) and activity of the expressed enzyme was assayed using para-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (pNP α-galactoside) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). The β-galactosidase subclone BA-bC was constructed by PCR amplification of the bgaC gene from the DNA template, using primers specific to the N- and C-terminal sequences. PCR product was ligated into the pΔα vector and transformed into E. coli DH5α cells to obtain the BA-bC construct.

Analysis of enzyme activity.

The AgaA enzyme was assayed in crude cell lysate for thermal dependence of activity on the substrate pNP α-galactoside (Sigma). One milliliter of the reaction buffer (Z buffer without β-mercaptoethanol [20]) and 200 μl of pNP α-galactoside (4 mg/ml) were preincubated at the assay temperature. The reaction was started by adding 10 μl of a 1:10 dilution of cell lysate. The assays were stopped with 500 μl of Na2CO3 and the intensity of the color change was measured at 420 nm. Substrate specificity of the α-galactosidase was determined using pNP substrates, where one unit of activity was defined as 1 μmol of pNP product released per min, and specific activity was expressed as micromoles of pNP product produced per minute per milligram of protein. Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) protein assay dye reagent concentrate with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Thermal dependence of activity for the BgaC enzyme in crude cell lysate was performed by measuring the product of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) hydrolysis at 420 nm, as described above. Thermal inactivation of the enzyme was also examined by incubating aliquots of crude cell lysate at 35, 40, and 45°C followed by measurement of the remaining activity with ONPG at 30°C.

Regulation of glycosyl hydrolase activity in C. piscicola strain BA.

The ability of C. piscicola strain BA to produce glycosyl hydrolase activity under various growth conditions was examined in 3-ml cultures containing M9 medium (6 g of Na2HPO4, 3 g of KH2PO4, 0.5 g of NaCl, and 1 g of NH4Cl per liter, 0.001 M MgSO4, 0.0001 M CaCl2) supplemented with 1 ml of trace elements solution per liter, 10 ml of Eagle Basal Vitamin solution (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) per liter, and 1% (wt/vol) concentrations of different commercial digests of soy (many of which have a high carbohydrate content). Cell yields in these semidefined media were determined by measuring the optical density of the culture at 600 nm. Whole-cell assays using 1 ml of each culture were performed by the method of Miller et al. (20), without β-mercaptoethanol, using ONPG as the chromogen. Determination of the effect of various carbon sources on the enzyme activities produced by C. piscicola strain BA was examined by culturing organisms in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) with different sugars at 2% (wt/vol). Enzyme assays were performed in duplicate due to substrate limitations, using the chromogenic substrates pNP α-galactopyranoside, pNP β-galactopyranoside, and pNP phospho-β-galactopyranoside (received from J. Thompson). The bicinchoninic acid reagent was used for the determination of protein content of whole-cell samples.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession numbers of the C. piscicola BA agaA and bgaC gene sequences are AF376480 and AF376481, respectively.

RESULTS

Fragment analysis.

A DNA fragment from C. piscicola strain BA that had been cloned into the pΔα vector conferred the ability to hydrolyze X-Gal on the E. coli strain DH5α. Three distinct open reading frames on this fragment were found to have sequence homology to different families of glycosyl hydrolases, families 36, 42, and 35 (GenBank accession numbers AF376480 and AF376481 and data not shown). Previous work analyzed the family 42 enzyme (6); however, the substrate specificity of two of the three encoded enzymes had not yet been verified. These two genes were subcloned into E. coli DH5α cells, and their expressed enzyme activities were examined independently.

Thermal dependence and specificity of BgaC.

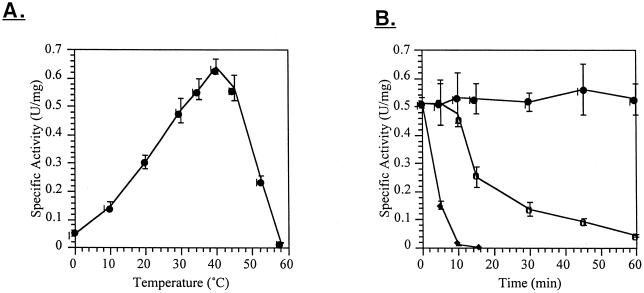

E. coli DH5α transformants carrying the DNA fragment BA4b-4 were able to hydrolyze the β-1,4-linked chromogenic β-galactosidase substrate X-Gal, as well as ONPG. Thermal dependence of activity assays of expressed BgaC were performed using ONPG as a substrate. The enzyme demonstrated peak activity at 37°C (Fig. 1A). The BgaC enzyme was stable at 40°C for at least 60 min, but rapidly became inactivated when incubated at 45°C (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Activity of BgaC in cell extracts. (A) Thermal dependence of activity, measured by endpoint assay after a 2- to 10-min incubation. (B) Thermal stability of enzyme activity after incubation at 40 (●), 45 (○), or 50°C (♦). Aliquots of enzyme were removed at different times and assayed for activity at 30°C.

The BgaC enzyme was stable in cell lysates at 4°C for several weeks and did not require the stabilizing presence of glycerol as did the previously reported BgaB enzyme (6). Another notable difference is that its activity is unaffected by 0.5 M NaCl and 0.04 M imidazole. BgaC was dialyzed against different metals in preparation for iminodiacetic acid (IDA) affinity purification. Unfortunately, the enzyme was inactivated by dialysis against 50 mM concentrations of CuCl2 and lost 17% of its activity when dialyzed against ZnCl2 and 38% when dialyzed against NiCl2 (data not shown). CuCl2 and NiCl2 are known to have detrimental effects on some proteins. The effect of ZnCl2 is intriguing, however, since Zn2+ is known to interact positively with some groups of β-galactosidases.

Thermal dependence and specificity of AgaA.

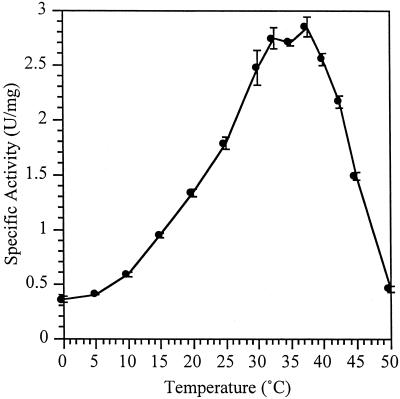

Transformants carrying the subcloned α-galactosidase gene agaA were unable to hydrolyze 5-bromo-3-chloro-2-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (X-α-Gal) on Luria-Bertani–ampicillin plates. However, permeabilized whole cells and cell extracts did contain an activity which hydrolyzed the chromogen ONP-α-Gal. The enzyme was also active on pNP α-galactoside and this was used for comparison with other pNP substrates. The specific activity with pNP α-galactoside was 2.3 U/mg. All substrates containing β-linkages (pNP β-fucoside, pNP β-galactoside, pNP β-mannoside, and pNP β-cellobioside) had less than 0.001% of the pNP α-galactosidase activity. When cell lysates were tested for the ability to hydrolyze pNP α-glucoside, no activity above the background found in the DH5α control cells was observed. Thermal dependence of activity of the AgaA enzyme (Fig. 2) indicated that it was most active within a range of 32 to 37°C.

FIG. 2.

Thermal dependence of activity of AgaA expressed in E. coli DH5α cells. Assays were performed with crude cell extracts using the chromogenic substrate pNP α-galactoside in 1xZ buffer without β-mercaptoethanol at pH 7.0.

Effect of growth conditions on enzyme activity in the native organism.

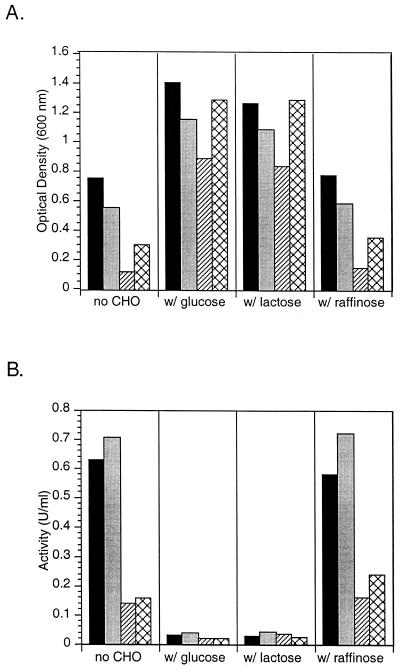

Like all other members of the Carnobacterium genus, strain BA requires a rich medium for growth and does not grow on a minimal medium, even when supplied with vitamins, minerals, and amino acids. Of all the common types of complex media tested (Luria-Bertani broth, nutrient broth, TSB, R2, yeast extract-malt [YM], Terrific broth), the organism had the highest cell yield on TSB. An ingredient of TSB, phytone, is a hydrolysate of soy containing a high carbohydrate content (35% dry weight). Other soy hydrolysates were tested by adding them to M9 medium in 1% (wt/vol) final concentrations to examine organism growth and gene expression. The yield and activity with ONPG of cells grown with the four best soy additives are shown in Fig. 3. While many of the complex additives permitted growth of the organism, the total cell yield remained highest with TSB. With all four of the media tested, addition of either 2% glucose or 2% lactose caused the cell yield to double, while additional raffinose did not cause a change in cell yield from that of controls with no additional carbohydrate.

FIG. 3.

Growth of C. piscicola strain BA cells on M9 with soy hydrolysate medium supplements. (A) Optical density of overnight cultures grown at 28°C and measured at 600 nm. (B) Specific activities from end-point assays using permeabilized whole cells. ONPG was used as the colorimetric substrate. Black bars, TSB only; gray bars, M9 plus phytone; hatched bars, M9 plus Pro-Tein (A. E. Staley Mfg. Co.); cross-hatched bars, M9 plus tryptone.

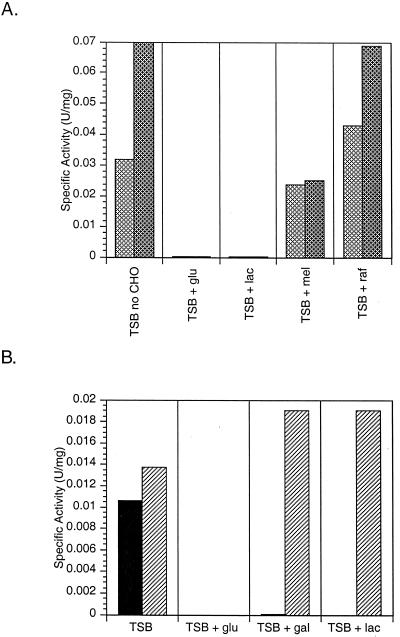

TSB was supplemented with a variety of carbon sources (2% [wt/vol]) in order to examine their effects on enzyme levels in the native organism. The addition of the α-galactoside raffinose to the medium had no significant effect on the observed α- and β-galactosidase activities (Fig. 4A), whereas supplementing the growth medium with the α-galactoside stachyose caused a reduction in both α- and β-galactosidase activities (data not shown). Glucose, and more interestingly, lactose, both decreased α- and β-galactosidase activities (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Enzymatic activity of C. piscicola strain BA whole cells grown in TSB supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) total sugar. All end-point assays were incubated at 20°C in the presence of a specific chromogen. (A) ONPG (darker cross-hatched bars) and pNP galactoside (lighter cross-hatched bars). (B) pNP galactoside (black bars) and pNP 6-phospho-galactoside (hatched bars).

Though no other β-galactosidase activities were observed during the creation of the C. piscicola strain BA chromosomal libraries, it is possible that the chromogens used in screening (X-Gal and ONPG) would not have detected them. Because other lactic acid bacteria use phospho-β-galactosidases during lactose utilization, we assayed C. piscicola strain BA cells for pNP 6-phospho-β-galactoside activity. Growth of cells in TSB supplemented with glucose still caused reduction of activity towards the phosphorylated substrate; however, unlike assays using pNP β-galactoside, activities on pNP phospho-β-galactoside were not reduced when cells were grown in the presence of galactose or lactose (Fig. 4B). This indicates that a third β-galactosidase, a phospho-β-galactosidase, was produced by the cells and that this enzyme would most likely be responsible for lactose utilization and the increased cell yield.

DISCUSSION

The discovery of two genes belonging to different families of β-galactosidases and their arrangement with an α-galactosidase gene on a single DNA fragment cloned from C. piscicola strain BA is presently unique among the lactic acid bacteria. This arrangement may be related to the interdependent function of the three encoded enzymes. If so, the study of these enzymes may help us understand the normal function of glycosyl hydrolases that have so far been identified only by their sequence homology with other enzymes. Characterization of the BgaB β-galactosidase was presented in a previous work (6). Here we have concentrated on the second β-galactosidase, BgaC, and the α-galactosidase, AgaA.

The sequence of the β-galactosidase BgaC is homologous to family 35 glycosyl hydrolases. Interestingly, the enzyme appears to be absent from most of the well-characterized lactic acid bacteria, including L. lactis, where a search of the entire genome detected no sequences homologous to BgaC. Assays at different temperatures with ONPG demonstrated that the enzyme has a thermal optimum of about 40°C. This optimum is lower than values for some other mesophilic enzymes, such as LacZ from E. coli (50 to 55°C) (17), BglI and II from Bacillus circulans (45° and 60°C, respectively) (27), or the β-galactosidase from Bacteroides polypragmatus (45°C) (22). In addition, this thermal optimum is nearly 10°C higher than that of the cold-active BgaB β-galactosidase encoded by the gene found directly upstream of bgaC. Despite the fact that the thermal optimum of BgaC is higher than that of the other β-galactosidase, it is still quite thermolabile, showing rapid inactivation at temperatures of 45 and 50°C.

The other gene that is part of this cluster encodes a family 36 α-galactosidase, AgaA. Similar enzymes have also been detected in two different strains of the thermophile Bacillus stearothermophilus, the AgaN enzyme from strain NUB3621 (9) and the GalA enzyme from strain MCA2184 (accession number AF038547). The optimal temperature for activity of the C. piscicola AgaA enzyme is 32 to 37°C, which is much lower than that of the B. stearothermophilus AgaN enzyme with a peak activity at 75°C. The GalA enzyme was not characterized with respect to thermal dependence; however, it retained full catalytic activity after incubation at 60°C for 24 h and therefore is likely to be much more stable than the C. piscicola BA enzyme. No data on thermal dependency of activity are available in the literature for the homologous α-galactosidases from the mesophiles L. plantarum (accession number AF189765) or Pediococcus pentosaceus (accession number L32093), and therefore the biochemical characteristics of these related enzymes from these mesophilic organisms cannot be compared.

The inability of C. piscicola strain BA to grow on minimal media made testing carbohydrate utilization difficult. In order to determine whether a carbon source was used by the cells, cultures were grown in rich medium (TSB) with and without added carbohydrate and then examined for increases in cell yield. When cells were grown in the presence of excess glucose, the cell yield increased. Furthermore, a simultaneous reduction in ONPG activity in these cultures suggested that the measured enzymes were subject to catabolite repression during growth with glucose. Cultures grown in TSB plus lactose also demonstrated an increased cell yield and decreased activity on ONPG. The similar decrease in the measured enzyme activities for cells grown with lactose also suggested that these enzymes were catabolite repressed. Because these enzyme activities were reduced rather than increased when lactose was added, it is unlikely that they are involved in lactose utilization.

None of the X-Gal-hydrolyzing transformants from chromosomal libraries of C. piscicola strain BA contained genes with homology to a family 1 phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phospho-β-galactosidase. However, it is possible that some phospho-β-galactosidases might not hydrolyze X-Gal and would be missed in these screens. Because chromogenic substrates for the phosphorylated galactosides are not commercially available, we obtained small quantities from J. Thompson that allowed us to test the possibility that a phospho-β-galactosidase might exist in our C. piscicola strain. Assays performed on lactose-grown cells using pNP phospho-β-galactopyranoside showed that there was indeed a phospho-β-galactosidase activity present in C. piscicola strain BA cells, one which was undetectable without the use of a phosphorylated chromogen. Thus, it seems likely that the glycosyl hydrolases discovered on our cloned gene fragment have a function beyond that of lactose hydrolysis.

It is often assumed that enzymes with the ability to hydrolyze X-Gal or ONPG function in the utilization of lactose by the cell. However, the disaccharide lactose, found almost exclusively in mammal milk, is relatively rare in soils, streams, etc. In contrast, oligosaccharides are common components of microbial cell walls and capsules as well as several eukaryotic structures. Thus, many of these enzymes may instead have important functions for providing alternative carbon sources. For example, recent work with α-galactosidases has indicated that these enzymes fill an essential role in the breakdown of side chains from large oligosaccharides such as hemicellulose and soy (10, 16). These enzymes are intracellular and are induced after breakdown of the target substrate's polymer backbone by extracellular enzymes such as β-mannanase (18). Both α- and β-linkages are common in the side chains of sugar polymers produced by plants and in the complex saccharides adsorbed to humic acid substances in the soil. Therefore the by-products from the breakdown of these larger sugar molecules may be targets of the C. piscicola strain BA enzymes.

The clustering of the genes encoding novel β- and α-galactosidases suggests that the enzymes may function in concert to degrade oligosaccharides containing both alpha and beta galactoside linkages. Preliminary results suggest that these genes are cotranscribed and may be regulated as an operon. The unique arrangement of the alpha and two different beta galactosidases together may provide a useful tool for helping us understand the prevalence and function of these enzymes in a variety of other microorganisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Phillips and members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank J. Thompson for generously providing samples of pNP phospho-β-galactopyranoside for our assays.

This work was supported by Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-93ER20117 from the Division of Energy Biosciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barakat R K, Griffiths M W, Harris L J. Isolation and characterization of Carnobacterium, Lactococcus, and Enterococcus sp. from cooked, modified atmosphere packaged, refrigerated poultry meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;62:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger J-L, Lee B H, Lacroix C. Purification, properties and characterization of a high-molecular-mass β-galactosidase isoenzyme from Thermus aquaticus YT-1. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1997;25:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breves R, Bronnenmeier K, Wild N, Lottspeich F, Staudenbauer W L, Hofemeister J. Genes encoding two different β-glucosidases of Thermoanaerobacter brockii are clustered in a common operon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3902–3910. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3902-3910.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins M D, Farrow J A E, Phillips B A, Ferusu S, Jones D. Classification of Lactobacillus divergens, Lactobacillus piscicola, and some catalase-negative, asporgenous, rod-shaped bacteria from poultry in a new genus. Carnobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:310–316. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins M D, Rodrigues U, Ash C, Aguirre M, Farrow J A E, Martinez-Murcia A, Phillips B A, Williams A M, Wallbanks S. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Lactobacillus and related lactic acid bacteria as determined by reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;77:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coombs J M, Brenchley J E. Biochemical and phylogenetic analysis of a cold-active β-galactosidase from the lactic acid bacterium Carnobacterium piscicola BA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5443–5450. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5443-5450.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vos W M, Vaughan E E. Genetics of lactose utilization in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;15:217–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franz C M, Stiles M E, van Belkum M J. Simple method to identify bacteriocin induction peptides and to auto-induce bacteriocin production at low cell density. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridjonsson O, Watzlawick H, Gehweiler A, Mattes R. Thermostable α-galactosidase from Bacillus stearothermophilus NUB3621: cloning, sequencing and characterization. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;176:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fridjonsson O, Watzlawick H, Gehweiler A, Rohrhirsch T, Mattes R. Cloning of the gene encoding a novel thermostable alpha-galactosidase from Thermus brockianus ITI360. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3955–3963. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.3955-3963.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutshall K R, Trimbur D E, Kasmir J J, Brenchley J E. Analysis of a novel gene and β-galactosidase isozyme from a psychrotrophic Arthrobacter isolate. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1981–1988. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1981-1988.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1993;293:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henrissat B, Davies G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes M L, Scopes R K, Moritz R L, Simpson R J, Englert C, Pfeifer F, Dyall-Smith M L. Purification and analysis of an extremely halophilic beta-galactosidase from Haloferax alicantei. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1337:276–286. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(96)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King M R, Yernool D A, Eveleigh D E, Chassy B M. Thermostable α-galactosidase from Thermotoga neapolitana: cloning, sequencing, and expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loveland J, Gutshall K, Kasmir J, Prema P, Brenchley J E. Characterization of psychrotrophic microorganisms producing β-galactosidase activities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:12–18. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.12-18.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolles-Clark E, Tenkanen M, Nakari-Setala T, Penttila M. Three α-galactosidase genes of Trichoderma reesei cloned by expression in yeast. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0104h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meltivier A, Pilet M F, Dousset X, Sorokine O, Anglade P, Zagorec M, Piard J C, Marion D, Cenatiempo Y, Fremaux C. Divercin V41, a new bacteriocin with two disulphide bonds produced by Carnobacterium divergens V41: primary structure and genomic organization. Microbiology. 1998;144:2837–2844. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paavilainen S, Hellman J, Korpela T. Purification, characterization, gene cloning, and sequencing of a new β-glucosidase from Bacillus circulans subsp. alkalophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:927–932. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.927-932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel G B, Mackenzie C R, Agnew B J. Properties and potential advantages of β-galactosidase from Bacteroides polypragmatus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1985;22:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ringo E, Holzapfel Identification and characterization of carnobacteria associated with the gills of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Syst Appl Microbiol. 2000;23:523–527. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(00)80026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schillinger U, Holzapfel W H. The genus Carnobacterium. In: Wood B J B, Holzapfel W H, editors. The genera of the lactic acid bacteria. New York, N.Y: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1995. pp. 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheridan P P, Brenchley J E. Characterization of a salt-tolerant family 42 beta-galactosidase from a psychrophilic Antarctic Planococcus isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2438–2444. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2438-2444.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trimber D E, Gutshall K R, Prema P, Brenchley J E. Characterization of a psychrotrophic Arthrobacter gene and its cold-active β-galactosidase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4544–4552. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4544-4552.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vetere A, Paoletti S. Separation and characterization of three β-galactosidases from Bacillus circulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1380:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]