Abstract

Objective:

Blood flow is the rate of blood movement and relevant to numerous processes, though understudied in gliomas. The aim of this review was to pool blood flow metrics obtained from MRI modalities in adult supratentorial gliomas.

Methods:

MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane database were queried 01/01/2000–31/12/2019. Studies measuring blood flow in adult Grade II–IV supratentorial gliomas using dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) MRI, dynamic contrast enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) or arterial spin labelling (ASL) were included. Absolute and relative cerebral blood flow (CBF), peritumoral blood flow and tumoral blood flow (TBF) were reported.

Results:

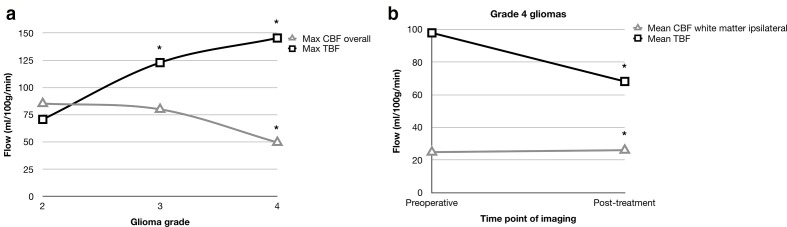

34 studies were included with 1415 patients and 1460 scans. The mean age was 52.4 ± 7.3 years. Most patients had glioblastoma (n = 880, 64.6%). The most common imaging modality was ASL (n = 765, 52.4%) followed by DSC (n = 538, 36.8%). Most studies were performed pre-operatively (n = 1268, 86.8%). With increasing glioma grade (II vs IV), TBF increased (70.8 vs 145.5 ml/100 g/min, p < 0.001) and CBF decreased (85.3 vs 49.6 ml/100 g/min, p < 0.001). In Grade IV gliomas, following treatment, CBF increased in ipsilateral (24.9 ± 1.2 vs 26.1 ± 0.0 ml/100 g/min, p < 0.001) and contralateral white matter (25.6 ± 0.2 vs 26.0± 0.0 ml/100 g/min, p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Our findings demonstrate that increased mass effect from high-grade gliomas impairs blood flow within the surrounding brain that can improve with surgery.

Advances in knowledge:

This systematic review demonstrates how mass effect from brain tumours impairs blood flow in the surrounding brain parenchyma that can improve with treatment.

Introduction

Perfusion is the process by which blood flows through tissue, provides nutrition and removes metabolic waste products. It can be quantified using imaging techniques, the gold-standard of which include radiolabelled water ([15O]-H2O)` positron emission tomography (PET) and Xenon-enhanced CT. In these techniques, a tracer is delivered to the tissue and leaves the vasculature producing changes in signal which directly reflect blood flow and capillary exchange, producing a true measurement of perfusion.1 However, these techniques cannot be performed in routine clinical practice. Recent advances have therefore attempted to quantify perfusion metrics using MRI.

MRI-derived perfusion metrics can aid in the diagnosis of gliomas.2 They can also aid understanding of several clinically relevant processes including angiogenesis, intracranial pressure effects, drug delivery, tumour infiltration and hypoxia.3–5 To date, the most widely studied MRI-derived perfusion metrics in the glioma literature are cerebral blood volume (CBV), which is the total volume of blood moving through a tissue per unit volume of brain, and the contrast transfer constant (Ktrans), which is a composite parameter reflecting both tissue blood flow and the capillary permeability surface area product.6,7 However, blood flow, representing the rate over which blood moves through a unit of tissue, is understudied though uniquely relevant to a wide range of biological processes.

MRI techniques to measure local blood flow can be split into contrast-based methods such as dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) and dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI, and non-contrast based methods such as arterial spin labelling (ASL).1 DSC relies on proton decay of transverse magnetisation induced by adjacent intra-arterial paramagnetic contrast media (T2* shortening effects). DCE also exploits contrast effects, but is based on recovery of proton longitudinal magnetisation (T1 shortening effects). ASL avoids exogenous contrast agent and instead, labels protons in the neck, usually by application of a 180 degree inversion radiofrequency pulse. These inverted protons subsequently flow into the region of interest and the signal differences between a pre- and post-inversion image are used to determine blood flow.8

To date, there is limited data on MRI derived blood flow metrics in adult supratentorial gliomas. The aim of this systematic review was to quantitatively pool blood flow metrics obtained from commonly used MRI modalities in adult supratentorial gliomas.

Methods and materials

Registration

The study protocol was registered on the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) under the ID number: CRD42019111578. The review was undertaken and the manuscript composed according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guidelines.

Literature search

The literature search strategy is outlined in Supplementary Table 1. All searches were conducted by two authors (MW and DL). MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were queried starting from 01/01/2000 to 31/12/2019 using the NICE Healthcare Databases Advanced Search (HDAS) service. References of included studies were examined to extract potential further papers that may have been missed during the initial systematic search. Two authors (MW and DL) screened titles, abstracts and full-texts independently to identify articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and review by a third author (EA).

Inclusion criteria

Articles meeting the following criteria were included in the study, grouped as per our Participants, Interventions, Comparisons and Outcomes (PICO) strategy:

- Participants:

- Adult patients (≥18 years)

- Minimum sample size = 5

- Diagnosis of WHO Grade II, III or IV glioma

- Treatment prior to imaging clearly described

-

Interventions

DSC, DCE or ASL imaging

-

Comparisons

Presentation of quantitative blood flow data by individual glioma grade.

-

Outcome

Absolute or relative blood flow metrics reported

Data extraction

For each study, data on patient characteristics, imaging modality, blood flow metrics and key confounding variables was extracted into an excel spreadsheet. Only results from study groups and subgroups with ≥5 patients were analysed. Differences and subsequent bias in blood flow results can be attributed to heterogeneity in imaging modality (DSC, DCE or ASL), region of interest (ROI) analysis, reference tissue selection for measurement of relative blood flow and the time point at which imaging is performed (e.g. pre-, post-operatively or at recurrence). Data on these variables were therefore collected to account for potential bias in reported outcomes and inform our analysis. For inclusion, studies must therefore have provided data on these confounding variables to minimise bias.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in each included study was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool that is designed for diagnostic studies.9 Two authors (MW and DL) agreed a set of standards for bias assessment using this tool prior to screening, particularly those relating to selection bias (e.g. consideration of which patients were excluded) and assessment of the reference standard (e.g. correlation to histological grade). These authors then screened each included study independently using the QUADAS-2 tool. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third author (EA).

Data analysis

Data on ROIs employed by studies was used to group reported blood flow metrics and create universal definitions (Table 1). Three main groups of flow metrics were considered, including: cerebral blood flow (CBF) relating to non-tumoral brain parenchyma; peritumoral flow – relating to signal abnormality beyond the enhancing edge of the glioma; and tumoral flow – relating to the tumour itself (defined variably as the total T1-enhancing hyperintensity or T2 hyperintensity).

Table 1.

Definitions of blood flow metrics extracted from studies based on ROIs

| Term | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| CBF | Mean CBF overall | Mean flow in whole brain minus tumour |

| Max CBF overall | Area of maximal flow in whole brain minus tumour | |

| Mean CBF white matter overall - both sides | Mean flow in white matter ipsilateral and contralateral to tumour | |

| Max CBF white matter overall - both sides | Area of maximal flow in white matter ipsilateral and contralateral to tumour | |

| Mean CBF white matter ipsilateral | Mean flow in white matter ipsilateral to tumour | |

| Mean CBF white matter contralateral | Mean flow in white matter contralateral to tumour | |

| Max CBF white matter contralateral | Area of maximal flow in white matter contralateral to tumour | |

| Max CBF grey matter contralateral | Area of maximal flow in grey matter contralateral to tumour | |

| Perilesional flow | Mean perilesional flow | Mean flow in non-enhancing T2 or FLAIR hyperintensity |

| Max perilesional flow | Area of maximal flow in non-enhancing T2 or FLAIR hyperintensity | |

| Mean relative perilesional flow - white matter reference | Mean perilesional flow/mean flow in ipsilateral or contralateral white matter | |

| Max relative perilesional flow - white matter reference | Max peri-lesional flow/mean flow in ipsilateral or contralateral white matter | |

| TBF | Mean TBF | Mean flow in tumour |

| Max TBF | Area of maximal flow in tumour | |

| Mean rTBF - all reference ROIs | Mean TBF/any reference ROI | |

| Mean rTBF - white matter reference | Mean TBF/mean flow in ipsilateral or contralateral white matter | |

| Mean rTBF - mixed | Mean TBF/area that includes both white matter and grey matter e.g. whole brain, contralateral mirror ROI | |

| Mean rTBF - grey matter reference | Mean TBF/mean flow in ipsilateral or contralateral grey matter | |

| Mean rTBF - cerebellum reference | Mean TBF/mean flow in any area of the cerebellum | |

| Max rTBF - all reference ROIs | Max TBF/any reference ROI | |

| Max rTBF - mixed | Max TBF/area that includes both white matter and grey matter e.g. whole brain, contralateral mirror ROI | |

| Max rTBF - white matter reference | Max TBF/mean flow in ipsilateral or contralateral white matter | |

| Max rTBF - grey matter reference | Max TBF/mean flow in ipsilateral or contralateral grey matter | |

| Max rTBF - cerebellum reference | Max TBF/mean flow in any area of the cerebellum |

CBF, cerebral blood flow; ROI, region of interest; TBF, tumoral blood flow.

Relative values were study defined and not generated.

Data were described as categorised by the following variables that can influence blood flow metrics:

Grade of glioma: results were presented separately for WHO Grade 2 (G2), Grade 3 (G3) and Grade 4 (G4) gliomas. Subgroup analysis was also performed between gliomas with an oligodendroglial component to those without.

Time point of imaging: pre-operative; post-treatment, where treatment refers to surgery ±radiotherapy/chemotherapy; and recurrence.

Type of imaging: contrast based – (DSC/DCE); and non-contrast based – (all types of ASL).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v. 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Absolute blood flow results were reported in ml/100 g/min whilst relative values were unit-less. Means were derived for each blood metric and provided with standard deviations. Means were weighted by study sample size as measures of variance were not reported often enough to allow inverse variance weighting for the majority of studies. Group comparisons were performed using independent t-tests (t-t) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), for two or three group comparisons, respectively. In the case of one-way ANOVA, post-hoc comparisons were performed using Bonferroni tests. The interrelation between two categorical variables of interest (time point of imaging and type of imaging) was modelled using a factorial ANOVA generalised linear model. A sensitivity analysis was performed for the most commonly reported blood flow metric using inverse variance weighting, including only studies that reported measures of variance.

Results

Literature search

A PRISMA flow diagram describing the literature search and study identification is provided (see Supplement). A total of 1770 unique records were identified and 195 full texts retrieved. 34 studies were included in the final quantitative analysis (Table 2).10–43

Table 2.

Study characteristics9–42

| Study | Imaging modality | Stage of imaging | nG2 | nG3 | nG4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hakyemez et al35 | DSC | Preoperative | 8 | 18 | |

| Wolf et al42 | CASL | Preoperative | 5 | 8 | 11 |

| Bastin et al31 | DSC | Preoperative | 10 | ||

| Kim et al37 | PASL | Preoperative | 11 | 7 | 15 |

| Haris et al36 | DCE | Preoperative | 17 | 7 | 35 |

| Kim et al38 | PASL | Preoperative | 26 | ||

| Weber et al41 | PASL, DSC | Preoperative | 12 | 26 | 24 |

| Server et al39 | DSC | Preoperative | 18 | 14 | 47 |

| Thomsen et al40 | DSC | Preoperative, post-treatment | 6 | 38 | |

| Fellah et al33 | DSC | Preoperative | 24 | 26 | |

| Artzi et al30 | DSC | Post-treatment | 14 | ||

| Falk et al32 | DSC, DCE | Preoperative | 18 | 7 | |

| Furtner et al34 | PASL | Preoperative | 14 | ||

| Andre et al10 | pCASL | Recurrence | 18 | ||

| Qiao et al24 | pCASL | Preoperative | 53 | ||

| Smitha et al25 | DSC | Preoperative | 15 | 18 | 7 |

| Lin et al19 | pCASL | Preoperative | 24 | ||

| Petr et al22 | pCASL | Post-treatment | 24 | ||

| Puig et al23 | DSC | Preoperative | 15 | ||

| Yang et al27 | PASL | Preoperative | 15 | 15 | 13 |

| Ganbold et al13 | pCASL | Preoperative | 25 | ||

| Kim et al16 | pCASL | Recurrence | 72 | ||

| Lin et al20 | DSC | Preoperative | 18 | 15 | |

| Zeng et al29 | pCASL | Preoperative | 13 | 17 | 28 |

| Brendle et al11 | DCE, PASL | Preoperative | 20 | ||

| Durmo et al12 | DSC | Preoperative | 10 | ||

| Han et al14 | pCASL | Preoperative | 92 | ||

| Khashbat et al15 | pCASL | Preoperative | 6 | ||

| Komatsu et al17 | ASL - type unspecified | Preoperative | 40 | 18 | 44 |

| Lee et al18 | DSC | Preoperative | 89 | ||

| Liu et al21 | pCASL | Preoperative | 22 | ||

| Stadlbauer et al26 | DSC | Preoperative, post-treatment | 57 | ||

| You et al28 | pCASL | Preoperative | 93 | ||

| Sengupta et al43 | DCE | Preoperative | 15 | 12 | 26 |

CASL, Continuous arterial spin labelling; DCE, Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI; DSC, Dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI; G2, WHO grade two gliomas; G3, WHO grade three gliomas; G4, WHO grade four gliomas; PASL, Pulsed arterial spin labelling; pCASL, Pseudo continuous-continuous arterial spin labelling.

34 studies were included in the final quantitative meta-analysis. Please note that the numbers refer to the number of patients in the study. Most studies reported imaging metrics at the preoperative stage. G4 tumours were the most commonly studied.

The overall risk of bias in included studies was low (see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). The major source of bias was in patient selection.

Patient and imaging characteristics

Blood flow metrics were reported in 1415 patients undergoing 1460 MRI studies. The mean age was 52.4 (±7.3) years. Glioma grades were as follows: G2 (n = 319, 22.5%), G3 (n = 190, 13.4%) and G4 (n = 906, 64.0%). The commonest imaging modality was ASL (n = 765, 52.4%), followed by DSC (n = 538, 36.8%) and DCE (n = 157, 10.8%). MRI studies were performed pre-operatively (n = 1268, 86.8%), post-treatment (n = 102, 7.0%) and at recurrence (n = 90, 6.2%).

Pre-operative flow metrics

The full list of pre-operative flow metrics by glioma grade is shown in Supplementary Table 3. The most commonly reported flow metric overall was max relative Tumoural Blood Flow (rTBF) - white matter reference, in 20 studies.

Most absolute blood flow values in cerebral and peritumoral areas were reported only for Grade IV gliomas (Supplementary Table 3). Pre-operatively, CBF values were as follows: overall - 30–50 ml/100 g/min; white matter - 20–30 ml/100 g/min; and grey matter - 70 ml/100 g/min. Peritumoral flow values were similar to CBF in white matter at around 15–25 ml/100 g/min.

Pre-operative tumour blood flow metrics are presented separately in Supplementary Table 4 together with 95% confidence intervals to aid diagnostic use. There was a clear stepwise increase in these values with glioma grade.

Flow metrics in which statistical comparison was possible between the different grades are shown in Table 3 and visually represented in Figure 1a. In pre-operative studies, all tumoral flow metrics increased with increasing glioma grade as shown in Table 3. For example, max TBF increased sequentially from G2 to G3 and G4 tumours (70.8 vs 122.9 vs 145.5, ANOVA, F = 56.9, p < 0.001). Relative max peritumoral flow showed a similar pattern (1.1 vs 1.3 vs 1.7, respectively; ANOVA, F = 39.8, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, total max CBF decreased with increasing glioma grade and this change was statistically significant between G2/G3 and G4 tumours (85.3/80.0 vs 49.6 ml/100 g/min, ANOVA, F = 39.7, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of pre-operative cerebral and tumoral blood flow metrics between glioma grades

| Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | ANOVA | Bonferroni | Factorial ANOVA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | R | N | M ± SD | R | N | M ± SD | R | N | |||||

| CBF | Max CBF overall | 85.3 (±0.0) | 1, 13 | 80.0 (±0.0) | 1, 17 | 49.6 (±20.0) | 35.2–77.0 | 2, 81 |

F = 39.7 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p > 0.99) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

|||

| Perilesional flow | Max perilesional relative flow - white matter reference | 1.1 (±0.0) | 2, 28 | 1.3 (±0.0) | 1, 14 | 1.7 (±0.4) | 1.1–2.0 | 2, 71 |

F = 39.8 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p = 0.215) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

|||

| TBF | Mean TBF | 34.2 (±20.2) | 4.2–51.7 | 6, 113 | 64.4 (±10.5) | 49.0–71.3 | 2, 26 | 98.0 (±34.5) | 49.0–136.5 | 7, 154 |

F = 167.1 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p < 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

Contrast: two vs 3: N/A two vs 4: MD = 53.8, p < 0.001 three vs 4: N/A Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 23.8, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 76.5, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 52.7, p < 0.001 |

| Max TBF | 70.8 (±13.8) | 46.9–85.8 | 4, 46 | 122.9 (±34.9) | 73.0–146.4 | 2, 25 | 145.5 (±48.0) | 74.5–250.0 | 6, 214 |

F = 56.9 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p < 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p = 0.042) |

||

| Mean rTBF - all reference ROIs | 1.5 (±0.6) | 0.9–1.7 | 7, 99 | 2.8 (±0.9) | 1.4–3.7 | 5, 49 | 3.8 (±2.1) | 1.6–7.9 | 6, 188 |

F = 63.9 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p < 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

Contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.98, p = 0.03 two vs 4: MD = 1.50, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 0.52, p = 0.40 Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 1.58, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 3.40, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 1.82, p < 0.001 |

|

| Mean rTBF - white matter reference | 1.8 (±0.5) | 1.3–2.7 | 4, 66 | 3.0 (±0.7) | 1.9–3.7 | 4, 41 | 4.0 (±2.1) | 2.1–8.0 | 5, 177 |

F = 40.2 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p = 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p = 0.007) |

Contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.98, p = 0.04 two vs 4: MD = 1.50, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 0.52, p = 0.41 Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 2.05, p = 0.002 two vs 4: MD = 3.71, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 1.66, p = 0.001 |

|

| Max rTBF - all reference ROIs | 1.9 (±0.8) | 1.0–3.5 | 14, 205 | 3.4 (±1.5) | 1.3–5.5 | 10, 138 | 5.1 (±2.5) | 1.6–9.5 | 13, 342 |

F = 179.2 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p < 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

Contrast based two vs 3: MD = 1.91, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 3.21, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 1.30, p = 0.35 Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.42, p = 0.225 two vs 4: MD = 3.53, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 3.11, p < 0.001 |

|

| Max rTBF - mixed | 1.7 (±0.3) | 1.3–2.0 | 3, 46 | 3.7 (±0.8) | 2.1–4.2 | 3, 41 | 5.7 (±2.7) | 2.3–9.5 | 5, 191 |

F = 60.3 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p < 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

Contrast based two vs 3: MD = 2.34, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 4.13, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 1.80, p = 0.001 Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.85, p = 0.506 two vs 4: MD = 4.34, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 3.49, p < 0.001 |

|

| Max rTBF - white matter reference | 2.1 (±0.9) | 1.0–3.5 | 8, 118 | 3.9 (±1.6) | 1.3–5.5 | 5, 69 | 4.8 (±1.9) | 1.6–7.3 | 6, 118 |

F = 100.5 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p < 0.001) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

Contrast based two vs 3: MD = 1.69, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 2.81, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 1.13, p < 0.001 Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.15, p = 0.756 two vs 4: MD = 0.50, p = 0.167 three vs 4: MD = 0.35, p = 0.519 |

|

| Max rTBF - grey matter reference | 1.2 (±0.4) | 0.6–1.5 | 3, 47 | 1.4 (±0.3) | 1.0–1.8 | 3, 43 | 2.1 (±0.3) | 1.7–2.7 | 3, 52 |

F = 96.3 p < 0.001 |

two vs 3 (p = 0.002) two vs 4 (p < 0.001) three vs 4 (p < 0.001) |

Contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.43, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 1.14, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 0.71, p < 0.001 Non-contrast based two vs 3: MD = 0.28, p < 0.001 two vs 4: MD = 0.98, p < 0.001 three vs 4: MD = 0.69, p < 0.001 |

|

ANOVA, One way analysis of variance; CBF, Cerebral blood flow; M ± SD, Mean±standard deviation; N, Number of studies followed by number of patients between studies; N/A, Current statistical test could not be performed; R, Range; ROI, Region of interest; TBF, Tumoral blood flow; rTBF, Relative tumoral blood flow.

This table shows the blood flow metrics that could be compared between different glioma grades. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Bonferroni tests, were undertaken to determine whether differences in mean values between glioma grades were statistically significant. This was further validated with a factorial ANOVA to control for the type of MR imaging used (contrast based or non-contrast based). With increasing glioma grade, tumoral and perilesional blood flow increased, whereas CBF decreased. All absolute flow metrics are in ml/100 g/min and all relative flow values are unitless.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of flow metrics. Statistical significance is denoted by an asterisk (*). (a) Line graph to show the relationship between histological glioma grade and absolute CBF and TBF. Opposite trends were observed such that an increase in the grade of glioma was accompanied by an increase in TBF (ANOVA, p < 0.001), but decrease in CBF (ANOVA, p < 0.001), presumably due to the increased mass effect from a high-grade glioma. (b) Line graph to show the relationship between the time point of imaging and CBF/TBF in Grade IV gliomas. Treatment in the form of surgery ± oncological chemoradiotherapy resulted in a decrease in TBF (t-t, p < 0.001), but increase in CBF (t-t, p < 0.001). CBF, cerebral blood flow; TBF, tumoral blood flow.

A subgroup comparison was performed between Grade II-III oligodendroglial tumors and pure astrocytic tumours, including results from those studies reporting exclusively on these tumour types. This analysis included 88 gliomas with oligodendroglial components and 60 pure astrocytic tumors. The max relative TBF with all reference ROIs was significant higher in oligodendroglial tumours (3.2 ± 2.4 vs 2.4 ± 1.1, t-t, t = 3.4, p < 0.001).

Type of imaging

Blood flow metrics were significantly different between contrast and non-contrast based MRI studies (Table 4). Where n > 30 for both imaging types (seven studies highlighted with an asterisk* in Table 4), non-contrast based methods produced significantly higher flow results for most measures (in five out of seven of these studies).

Table 4.

Comparison of pre-operative flow metrics obtained by contrast and non-contrast MRI studies

| Contrast-based | Non-contrast-based | T-test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | R | N | M ± SD | R | N | ||

| Max perilesional flow | 23.7 ± 0.0 | 1, 15 | 26.4 ± 0.5 | 26.2–27.4 | 2, 117 | t = 60.0, p < 0.001 | |

| Max perilesional relative flow - white matter reference | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.1–2.0 | 4, 89 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 1, 24 | t = 10.1, p < 0.001 | |

| Mean TBF* | 42.6 ± 25.0 | 4.2–63.9 | 4, 70 | 79.1 ± 41.5 | 12.1–136.5 | 11, 223 | t = 9.0, p < 0.001 |

| Max TBF | 151.6 ± 0.0 | 1, 15 | 130.4 ± 52.3 | 46.9–250.0 | 11, 270 | t = 6.7, p < 0.001 | |

| Mean rTBF - all reference ROIs* | 2.9 ± 2.0 | 1.5–7.9 | 3, 192 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 0.9–5.7 | 6, 144 | t = 0.59, p = 0.56 |

| Mean rTBF - white matter reference* | 2.9 ± 2.0 | 1.5–7.9 | 3, 192 | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 1.3–5.7 | 3, 92 | t = 5.6, p < 0.001 |

| Max rTBF - all reference ROIs* | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 1.0–7.3 | 20, 355 | 3.5 ± 2.9 | 1.0–9.5 | 17, 330 | t = 3.0, p = 0.003 |

| Max rTBF - mixed* | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 1.7–5.9 | 5, 109 | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 1.3–9.5 | 6, 169 | t = 5.1, p < 0.001 |

| Max rTBF - white matter reference* | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 1.0–7.3 | 15, 246 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.1–1.6 | 4, 59 | t = 24.2, p < 0.001 |

| Max rTBF - grey matter reference* | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.6–1.7 | 3, 46 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0–2.7 | 6, 96 | t = 6.6, p < 0.001 |

ANOVA, One way analysis of variance; CBF, Cerebral blood flow; M ± SD, Mean±standard deviation; N, Number of studies followed by number of patients between studies; N/A, Current statistical test could not be performed; R, Range; ROI, Region of interest; TBF, Tumoral blood flow; rTBF, Relative tumoral blood flow.

This table shows blood flow metrics that were comparable between contrast and non-contrast based MRI studies. Where n > 30 for both imaging types (*), there was a trend for non-contrast based methods to produce higher flow results. All absolute flow metrics are in ml/100 g/min and all relative flow values are unitless.

Time point of imaging

Time point comparison of blood flow metrics was only possible for G2 and G4 tumours. This analysis was limited due to the small number of studies reporting on post-treatment and recurrence blood flow metrics. In G2 tumours, only one study reported on post-treatment max relative TBF (relative to white matter), with a significant increase in this parameter compared to the pre-operative stage (2.1 ± 0.9 vs 2.6 ± 0, t-t, t = 6.8, p < 0.001).

Time point comparison for G4 tumours is shown in Table 5 and visually represented in Figure 1b. Following treatment (surgery ± oncological therapy), there were marginal but statistically significant increases in mean CBF in ipsilateral (24.9 ± 1.2 vs 26.1±0.0 ml/100 g/min, t-t, t = 6.79, p < 0.001) and contralateral white matter (25.6 ± 0.2 vs 26.0±0.0 ml/100 g/min, t-t, t = 20.0, p < 0.001). This was accompanied by variable changes in TBF. There was a significant reduction in mean TBF (98.0 ± 34.5 vs 68.2±0.0 ml/100 g/min, t-t, t = 10.7, p < 0.001), but increase in relative flow values (Table 5). At recurrence, there were significant reductions in all flow metrics compared to the pre-operative stage.

Table 5.

Serial comparison of cerebral and tumoral blood flow metrics at different time points in patients with glioblastoma

| Pre-op | Post-treatment | Recurrence | Pre-op vs Post-treatment |

Pre-op vs Recurrence | ANOVA (all stages) |

Bonferroni | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | R | N | M ± SD | R | N | M ± SD | R | N | |||||

| Max CBF overall | 49.6 ± 20.0 | 35.2–77.0 | 2, 81 | 35.0 ± 0.0 | 1, 18 |

t = 11.0, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| Mean CBF white matter ipsilateral | 24.9 ± 1.2 | 23.7–26.1 | 2, 49 | 26.1 ± 0.0 | 1, 32 |

t = 6.79, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| Mean CBF white matter contralateral | 25.6 ± 0.2 | 25.4–25.7 | 2, 49 | 26.0 ± 0.0 | 1, 32 |

t = 20.0, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| Mean perilesional flow | 15.5 ± 3.3 | 13.5–20.6 | 2, 35 | 18.8 ± 0.0 | 1, 32 |

t = 5.9, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| Mean TBF | 98.0 ± 34.5 | 49.0–136.5 | 7, 154 | 68.2 ± 0.0 | 1, 32 |

t = 10.7, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| Max TBF | 145.5 ± 48.0 | 74.5–250.0 | 6, 214 | 75.0 ± 15.1 | 45.0–82.5 | 2, 90 |

t = 16.5, p < 0.001 |

||||||

| Max rTBF - all reference ROIs | 5.1 ± 2.5 | 1.6–9.5 | 13, 342 | 5.4 ± 0.0 | 1, 26 | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 1, 72 |

t = 2.6, p = 0.009 |

F = 15.4, p < 0.001 |

Pre-op vs Post-op, p = 0.016 Pre-op vs first recurrence, p < 0.001 Post-op vs first recurrence, p < 0.001 |

|||

| Max rTBF - white matter reference | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 1.6–7.3 | 6, 118 | 5.4 ± 0.0 | 1, 26 | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 1, 72 |

t = 3.23, p = 0.002 |

F = 23.0, p < 0.001 |

Pre-op vs Post-op, p < 0.001 Pre-op vs first recurrence, p < 0.001 Post-op vs first recurrence, p < 0.001 |

|||

ANOVA, One way analysis of variance; CBF, Cerebral blood flow; M ± SD, Mean±standard deviation; N, Number of studies followed by number of patients between studies; N/A, Current statistical test could not be performed; R, Range; ROI, Region of interest; TBF, Tumoral blood flow; rTBF, Relative tumoral blood flow.

Results were compared at three different time points: preoperatively, post-treatment (after surgery ±adjuvant treatment) and at recurrence. Comparisons were made using independent t-tests or one-way analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni tests, as required. There was a marginal but significant increase in CBF following treatment. Changes in TBF were more variable, with a reduction in absolute mean TBF, but increase in rTBF. All absolute flow metrics are in ml/100 g/min and all relative flow values are unitless.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis of max rTBF (relative to white matter) revealed a serial increase with increasing tumour grade (ANOVA, F = 286.3, p < 0.001). Changes were significant when comparing G2 and G3 (Post-hoc Bonferroni, p < 0.001), G2 and G4 (Post-hoc Bonferroni, p < 0.001) and G3 and G4 (Post-hoc Bonferroni, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we reported blood flow characteristics in gliomas obtained from conventional MRI sequences – DSC, DCE or ASL. Pre-operative TBF and peritumoral flow increased with increasing tumour grade and was associated with a corresponding decrease in CBF. TBF was also higher in oligodendrogliomas compared to astrocytomas. Although only a handful of studies reported post-treatment results, CBF seemed to increase marginally, with variable changes reported for relative and absolute TBF. Non-contrast based imaging modalities (ASL) tended to produce higher flow results.

We found that TBF increases with increasing glioma grade. In contrast to normal brain vasculature, glioma vessels have increased total vessel surface area, branch points and vessel length, but reduced diameter and branch length.44 They can also aggregate to form complex glomeruloid structures, with increased gap between endothelial cells to facilitate vascular leak.45 These characteristics transition from less to more frequent with increasing glioma grade.46,47 However, the net effect of these vascular changes is increased flow with increasing glioma grade, despite some features producing increased resistance to flow (increased branch points, increased permeability) and decreased local flow (increased vessel length, decreased vessel diameter). Presumably, the net effect of increased total vessel surface area outweighs that of the other factors.

The higher TBF in oligodendrogliomas versus astrocytomas corresponds to prior reports of a higher cerebral blood volumes (CBVs).48 The exact reasoning for this is unclear. One explanation relates to oligodendroglioma vasculature, often described as a network of regular fine branching capillaries, resulting in a “chicken wire” appearance on imaging. Oligodendrogliomas vessels also have a larger mean vessel size to facilitate greater flow.49 Another explanation relates to the preferentially cortical location of oligodendrogliomas, arising mostly in grey matter, which has a higher flow rate than white matter.48

Absolute flow metrics were sparsely reported. In Grade IV gliomas, absolute pre-operative CBF values were 30–50 ml/100 g/min overall, 20–30 ml/100 g/min in white matter, and 70 ml/100 g/min in grey matter. These values are similar, but not completely homologous, to those reported in healthy volunteers.50,51 Therefore, relative flow metrics such as rTBF are less useful than absolute metrics, as they assume normality in normal appearing tissue, whereas our data suggest this is not a valid assumption. There is also variation in perfusion metrics across normal tissue such that their mean value is not a useful reference marker.50,51 Tumour-related raised intracranial pressure may also impact relative flow metrics more so than absolute values in the setting of impaired autoregulation, which is found in a high proportion of brain tumour patients.52

Non-contrast based imaging modalities tended to produce higher results. Prior studies comparing ASL to quantitative [15O]-H2O PET in healthy volunteers have also reported a tendency for the former to overestimate flow values.53 However, evidence to the contrary also exists, and in one study comparing ASL and DSC in the ischaemic penumbra of cerebral infarcts, ASL tended to underestimate true blood flow compared to DSC, producing in turn a higher total hypoperfusive tissue volume.54 Studies using ASL have highlighted the importance of a long enough post-labelling delay to produce robust results.55 Limitations of ASL techniques include their relatively low signal-to-noise ratio in comparison to DSC/DCE, sensitivity to motion due to reliance on image subtraction, and potential for discrepant results in elderly patients due to prolonged arterial transit.56

There are important limitations of contrast-based imaging techniques that could limit interpretation of our results, given that most data were derived from these techniques. The spatial resolution of both DSC and DCE is limited. In DSC, the main sources of error are: susceptibility artefacts around air-bone interfaces, especially at the skull base; tissue contrast leakage effects as a result of blood-brain-barrier breakdown and strong relaxation effects on T2*; and systematic errors from the assumption of uniform tissue relaxivity and blood haematocrit.57–59 In DCE, errors can arise from these same factors and in addition: motion artefacts resulting from a longer data acquisition time; differences in contrast timing and dose; and the kinetic model used for data analysis.60–63

Blood flow can be measured using imaging modalities not included in this review. MRI-based modalities include diffusion-weighted MRI using intravoxel incoherent motion and phase contrast angiography.64,65 Non-MRI modalities include CT perfusion, Xenon enhanced CT, Single Photon Emission CT (SPECT) and [15O]-H2O PET. Studies using these techniques have similarly reported increasing TBF with glioma grade.65–68

A better understanding of glioma perfusion has several applications. Blood flow metrics could aid in selecting patients for antivascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment.69 Knowledge of blood flow in addition to other perfusion metrics, could guide treatment planning and chemotherapy dose adjustment, and serve as a marker of treatment response.10 Blood flow metrics could help to better define the tumour edge to aid operative resection.70 They could also provide an indication of cerebral perfusion pressure, which in turn could help determine the urgency of surgical intervention.71

Limitations of the current review include the fact that different software packages/analytical processing methods to extract blood flow metrics, were not accounted for, this is especially relevant for ASL, for which several processing models exist. This includes quality control measures during measurement of blood flow to avoid extreme values (e.g. excluding necrotic areas, major vessels within the regions of interest). Different imaging protocols between studies were also not considered. However, arguably, attempting to adjust for these factors would have reduced the overall number of results that could be aggregated and made our methodology overly complex. The majority of studies presented results at the pre-operative stage such that interpretation of flow metrics at other time points - post-treatment and recurrence, was limited by study size and number. There was a lack of data on glioma genomics and how they relate to blood flow.

Conclusion

This study represents the first systematic review of MRI derived blood flow metrics in adult supratentorial gliomas. Pooling data from 3 MRI sequences – DSC, DCE and ASL, we reported blood flow metrics related to the tumor, peritumoral area and normal surrounding brain parenchyma. Pre-operative TBF and peritumoral flow increased with increasing tumour grade and was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in CBF. TBF was higher in oligodendrogliomas compared to astrocytomas. After treatment, there were marginal increases in CBF, presumably relating to relief of mass effect. ASL techniques tended to overestimate flow metrics in comparison to DSC/DCE. Our results have a number of potential applications and aid understanding of perfusion in adult gliomas.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and supervision of study: DC, AJ. Registration and protocol design: MW, DL, EA. Database searching and results: MW, DL, EA. Screening results for inclusion: MW, DL, EA, DC. Data extraction: MW, DC. Data analysis: MW, DL, MG. Preparation of first manuscript draft: MW, DL, EA, MG, DC, AJ. Revision and approval of final manuscript draft: EA, DC, AJ.

Availability of data and material: Supplementary material can be found online.

Contributor Information

Mueez Waqar, Email: Mueez.waqar@manchester.ac.uk.

Daniel Lewis, Email: daniel.lewis-3@postgrad.manchester.ac.uk.

Erjon Agushi, Email: erjon_a@hotmail.com.

Matthew Gittins, Email: Matthew.Gittins@manchester.ac.uk.

Alan Jackson, Email: Alan.Jackson@manchester.ac.uk.

David Coope, Email: David.Coope@manchester.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson A, O'Connor J, Thompson G, Mills S. Magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in neuro-oncology. Cancer Imaging 2008; 8: 186–99. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2008.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Law M, Yang S, Wang H, Babb JS, Johnson G, Cha S, et al. Glioma grading: sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of perfusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging compared with conventional MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24: 1989–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blystad I, Warntjes JBM, Smedby Örjan, Lundberg P, Larsson E-M, Tisell A. Quantitative MRI for analysis of peritumoral edema in malignant gliomas. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0177135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stivaros SM, Jackson A. Changing concepts of cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics: role of phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging and implications for cerebral microvascular disease. Neurotherapeutics 2007; 4: 511–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rissanen TT, Korpisalo P, Markkanen JE, Liimatainen T, Ordén M-R, Kholová I, et al. Blood flow remodels growing vasculature during vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy and determines between capillary arterialization and sprouting angiogenesis. Circulation 2005; 112: 3937–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcaide-Leon P, Pareto D, Martinez-Saez E, Auger C, Bharatha A, Rovira A. Pixel-by-Pixel comparison of volume transfer constant and estimates of cerebral blood volume from dynamic contrast-enhanced and dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging in high-grade gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 871–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 10: 223–32. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, Günther M, Hendrikse J, Hernandez-Garcia L, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: a consensus of the ISMRM perfusion Study Group and the European Consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73: 102–16. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andre JB, Nagpal S, Hippe DS, Ravanpay AC, Schmiedeskamp H, Bammer R, et al. Cerebral blood flow changes in glioblastoma patients undergoing bevacizumab treatment are seen in both tumor and normal brain. Neuroradiol J 2015; 28: 112–9. doi: 10.1177/1971400915576641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brendle C, Hempel J-M, Schittenhelm J, Skardelly M, Tabatabai G, Bender B, et al. Glioma grading and determination of IDH mutation status and ATRX loss by DCE and ASL perfusion. Clin Neuroradiol 2018; 28: 421–8. doi: 10.1007/s00062-017-0590-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durmo F, Lätt J, Rydelius A, Engelholm S, Kinhult S, Askaner K, et al. Brain tumor characterization using Multibiometric evaluation of MRI. Tomography 2018; 4: 14–25. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2017.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganbold M, Harada M, Khashbat D, Abe T, Kageji T, Nagahiro S. Differences in high-intensity signal volume between arterial spin labeling and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging may be useful for differentiating glioblastoma from brain metastasis. J Med Invest 2017; 64(1.2): 58–63. doi: 10.2152/jmi.64.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Y, Yan L-F, Wang X-B, Sun Y-Z, Zhang X, Liu Z-C, et al. Structural and advanced imaging in predicting MGMT promoter methylation of primary glioblastoma: a region of interest based analysis. BMC Cancer 2018; 18: 215. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khashbat D, Harada M, Abe T, Ganbold M, Iwamoto S, Uyama N, et al. Diagnostic performance of arterial spin labeling for grading nonenhancing astrocytic tumors. Magn Reson Med Sci 2018; 17: 277–82. doi: 10.2463/mrms.mp.2017-0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim C, Kim HS, Shim WH, Choi CG, Kim SJ, Kim JH. Recurrent glioblastoma: combination of high cerebral blood flow with MGMT promoter methylation is associated with benefit from low-dose temozolomide rechallenge at first recurrence. Radiology 2017; 282: 212–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komatsu K, Wanibuchi M, Mikami T, Akiyama Y, Iihoshi S, Miyata K, et al. Arterial spin labeling method as a supplemental predictor to distinguish between high- and low-grade gliomas. World Neurosurg 2018; 114: e495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee B, Park JE, Bjørnerud A, Kim JH, Lee JY, Kim HS. Clinical value of vascular permeability estimates using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI: improved diagnostic performance in distinguishing hypervascular primary CNS lymphoma from glioblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018; 39: 1415–22. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, Xue Y, Duan Q, Sun B, Lin H, Huang X, et al. The role of cerebral blood flow gradient in peritumoral edema for differentiation of glioblastomas from solitary metastatic lesions. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 69051–9. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y, Xing Z, She D, Yang X, Zheng Y, Xiao Z, et al. Idh mutant and 1p/19q co-deleted oligodendrogliomas: tumor grade stratification using diffusion-, susceptibility-, and perfusion-weighted MRI. Neuroradiology 2017; 59: 555–62. doi: 10.1007/s00234-017-1839-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T, Cheng G, Kang X, Xi Y, Zhu Y, Wang K, et al. Noninvasively evaluating the grading and IDH1 mutation status of diffuse gliomas by three-dimensional pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling and diffusion-weighted imaging. Neuroradiology 2018; 60: 693–702. doi: 10.1007/s00234-018-2021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petr J, Platzek I, Seidlitz A, Mutsaerts HJMM, Hofheinz F, Schramm G, et al. Early and late effects of radiochemotherapy on cerebral blood flow in glioblastoma patients measured with non-invasive perfusion MRI. Radiother Oncol 2016; 118: 24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puig J, Sánchez-González J, Blasco G, Daunis-I-Estadella P, Federau C, Alberich-Bayarri Ángel, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion metrics as potential biomarkers for survival in glioblastoma. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0158887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiao XJ, Ellingson BM, Kim HJ, Wang DJJ, Salamon N, Linetsky M, et al. Arterial spin-labeling perfusion MRI stratifies progression-free survival and correlates with epidermal growth factor receptor status in glioblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 672–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smitha KA, Gupta AK, Jayasree RS. Relative percentage signal intensity recovery of perfusion metrics—an efficient tool for differentiating grades of glioma. Br J Radiol 2015; 88: 20140784. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stadlbauer A, Mouridsen K, Doerfler A, Bo Hansen M, Oberndorfer S, Zimmermann M, et al. Recurrence of glioblastoma is associated with elevated microvascular transit time heterogeneity and increased hypoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 422–32. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17694905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang S, Zhao B, Wang G, Xiang J, Xu S, Liu Y, et al. Improving the grading accuracy of astrocytic neoplasms noninvasively by combining timing information with cerebral blood flow: a Multi-TI arterial spin-labeling MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 2209–16. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You S-H, Yun TJ, Choi HJ, Yoo R-E, Kang KM, Choi SH, et al. Differentiation between primary CNS lymphoma and glioblastoma: qualitative and quantitative analysis using arterial spin labeling MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2018; 28: 3801–10. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5359-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng Q, Jiang B, Shi F, Ling C, Dong F, Zhang J. 3D Pseudocontinuous arterial spin-labeling MR imaging in the preoperative evaluation of gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017; 38: 1876–83. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artzi M, Bokstein F, Blumenthal DT, Aizenstein O, Liberman G, Corn BW, et al. Differentiation between vasogenic-edema versus tumor-infiltrative area in patients with glioblastoma during bevacizumab therapy: a longitudinal MRI study. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: 1250–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bastin ME, Carpenter TK, Armitage PA, Sinha S, Wardlaw JM, Whittle IR. Effects of dexamethasone on cerebral perfusion and water diffusion in patients with high-grade glioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 402–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falk A, Fahlström M, Rostrup E, Berntsson S, Zetterling M, Morell A, et al. Discrimination between glioma grades II and III in suspected low-grade gliomas using dynamic contrast-enhanced and dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MR imaging: a histogram analysis approach. Neuroradiology 2014; 56: 1031–8. doi: 10.1007/s00234-014-1426-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fellah S, Caudal D, De Paula AM, Dory-Lautrec P, Figarella-Branger D, Chinot O, et al. Multimodal MR imaging (diffusion, perfusion, and spectroscopy): is it possible to distinguish oligodendroglial tumor grade and 1p/19q codeletion in the pretherapeutic diagnosis? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 1326–33. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furtner J, Bender B, Braun C, Schittenhelm J, Skardelly M, Ernemann U, et al. Prognostic value of blood flow measurements using arterial spin labeling in gliomas. PLoS One 2014; 9: e99616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hakyemez B, Erdogan C, Ercan I, Ergin N, Uysal S, Atahan S. High-grade and low-grade gliomas: differentiation by using perfusion MR imaging. Clin Radiol 2005; 60: 493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haris M, Husain N, Singh A, Husain M, Srivastava S, Srivastava C, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced derived cerebral blood volume correlates better with leak correction than with no correction for vascular endothelial growth factor, microvascular density, and grading of astrocytoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2008; 32: 955–65. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31816200d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HS, Kim SY. A prospective study on the added value of pulsed arterial spin-labeling and apparent diffusion coefficients in the grading of gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 1693–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim MJ, Kim HS, Kim J-H, Cho K-G, Kim SY. Diagnostic accuracy and interobserver variability of pulsed arterial spin labeling for glioma grading. Acta Radiol 2008; 49: 450–7. doi: 10.1080/02841850701881820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Server A, Graff BA, Orheim TED, Schellhorn T, Josefsen R, Gadmar Øystein B, et al. Measurements of diagnostic examination performance and correlation analysis using microvascular leakage, cerebral blood volume, and blood flow derived from 3T dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging in glial tumor grading. Neuroradiology 2011; 53: 435–47. doi: 10.1007/s00234-010-0770-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomsen H, Steffensen E, Larsson E-M, Perfusion MRI. Perfusion MRI (dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging) with different measurement approaches for the evaluation of blood flow and blood volume in human gliomas. Acta Radiol 2012; 53: 95–101. doi: 10.1258/ar.2011.110242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber M-A, Henze M, Tüttenberg J, Stieltjes B, Meissner M, Zimmer F, et al. Biopsy targeting gliomas: do functional imaging techniques identify similar target areas? Invest Radiol 2010; 45: 755–68. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ec9db0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf RL, Wang J, Wang S, Melhem ER, O'Rourke DM, Judy KD, et al. Grading of CNS neoplasms using continuous arterial spin labeled perfusion MR imaging at 3 tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005; 22: 475–82. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sengupta A, Ramaniharan AK, Gupta RK, Agarwal S, Singh A. Glioma grading using a machine-learning framework based on optimized features obtained from T1 perfusion MRI and volumes of tumor components. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 50: 1295–306. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radbruch A, Eidel O, Wiestler B, Paech D, Burth S, Kickingereder P, et al. Quantification of tumor vessels in glioblastoma patients using time-of-flight angiography at 7 Tesla: a feasibility study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e110727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rojiani AM, Dorovini-Zis K. Glomeruloid vascular structures in glioblastoma multiforme: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Neurosurg 1996; 85: 1078–84. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.6.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vajkoczy P, Menger MD. Vascular microenvironment in gliomas. J Neurooncol 2000; 50(1-2): 99–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1006474832189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gi T, Sato Y, Tokumitsu T, Yamashita A, Moriguchi-Goto S, Takeshima H, et al. Microvascular proliferation of brain metastases mimics glioblastomas in squash cytology. Cytopathology 2017; 28: 228–34. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cha S, Tihan T, Crawford F, Fischbein NJ, Chang S, Bollen A, et al. Differentiation of low-grade oligodendrogliomas from low-grade astrocytomas by using quantitative blood-volume measurements derived from dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 266–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo H, Kang H, Tong H, Du X, Liu H, Tan Y, et al. Microvascular characteristics of lower-grade diffuse gliomas: investigating vessel size imaging for differentiating grades and subtypes. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 1893–902. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5738-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grüner JM, Paamand R, Højgaard L, Law I. Brain perfusion CT compared with15O-H2O-PET in healthy subjects. EJNMMI Res 2011; 1: 28. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramsay SC, Murphy K, Shea SA, Friston KJ, Lammertsma AA, Clark JC, et al. Changes in global cerebral blood flow in humans: effect on regional cerebral blood flow during a neural activation task. J Physiol 1993; 471: 521–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma D, Bithal PK, Dash HH, Chouhan RS, Sookplung P, Vavilala MS. Cerebral autoregulation and CO2 reactivity before and after elective supratentorial tumor resection. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2010; 22: 132–7. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181c9fbf1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okazawa H, Higashino Y, Tsujikawa T, Arishima H, Mori T, Kiyono Y, et al. Noninvasive method for measurement of cerebral blood flow using O-15 water PET/MRI with ASL correlation. Eur J Radiol 2018; 105: 102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y-C, Liu H-L, Lee J-D, Yang J-T, Weng H-H, Lee M, et al. Comparison of arterial spin labeling and dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MRI in patients with acute stroke. PLoS One 2013; 8: e69085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fan AP, Guo J, Khalighi MM, Gulaka PK, Shen B, Park JH, et al. Long-Delay arterial spin labeling provides more accurate cerebral blood flow measurements in moyamoya patients: a simultaneous positron emission Tomography/MRI study. Stroke 2017; 48: 2441–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu Q, Liu Q, Ge H, Ge X, Wu J, Qu J, et al. Tumor recurrence versus treatment effects in glioma: a comparative study of three dimensional pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling and dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging. Medicine 2017; 96: e9332. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiselev VG. On the theoretical basis of perfusion measurements by dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med 2001; 46: 1113–22. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willats L, Calamante F. The 39 steps: evading error and deciphering the secrets for accurate dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI. NMR Biomed 2013; 26: 913–31. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calamante F, Connelly A, van Osch MJP. Nonlinear DeltaR*2 effects in perfusion quantification using bolus-tracking MRI. Magn Reson Med 2009; 61: 486–92. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parker GJ, Baustert I, Tanner SF, Leach MO. Improving image quality and T(1) measurements using saturation recovery turboFLASH with an approximate K-space normalisation filter. Magn Reson Imaging 2000; 18: 157–67. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00124-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buckley DL. Uncertainty in the analysis of tracer kinetics using dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med 2002; 47: 601–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Landis CS, Li X, Telang FW, Coderre JA, Micca PL, Rooney WD, et al. Determination of the MRI contrast agent concentration time course in vivo following bolus injection: effect of equilibrium transcytolemmal water exchange. Magn Reson Med 2000; 44: 563–74. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li K-L, Lewis D, Jackson A, Zhao S, Zhu X. Low-dose T1W DCE-MRI for early time points perfusion measurement in patients with intracranial tumors: a pilot study applying the microsphere model to measure absolute cerebral blood flow. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 48: 543–57. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Juhász J, Lindner T, Riedel C, Margraf NG, Jansen O, Rohr A. Quantitative phase-contrast Mr angiography to measure hemodynamic changes in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018; 39: 682–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Federau C, Meuli R, O'Brien K, Maeder P, Hagmann P. Perfusion measurement in brain gliomas with intravoxel incoherent motion MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 256–62. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mineura K, Yasuda T, Kowada M, Shishido F, Ogawa T, Uemura K. Positron emission tomographic evaluation of histological malignancy in gliomas using oxygen-15 and fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose. Neurol Res 1986; 8: 164–8. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1986.11739749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakagawa T, Tanaka R, Takeuchi S, Takeda N. Haemodynamic evaluation of cerebral gliomas using XeCT. Acta Neurochir 1998; 140: 223–34. doi: 10.1007/s007010050089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fainardi E, Di Biase F, Borrelli M, Saletti A, Cavallo M, Sarubbo S, et al. Potential role of CT perfusion parameters in the identification of solitary intra-axial brain tumor grading. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2010; 106: 283–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-98811-4_53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yun TJ, Cho HR, Choi SH, Kim H, Won J-K, Park S-W, et al. Antiangiogenic effect of bevacizumab: application of arterial spin-labeling perfusion MR imaging in a rat glioblastoma model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1650–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aprile I, Roscetti M, Giulianelli G, Muti M, Ottaviano P. Cerebral Mr perfusion imaging analysis of peritumoral tissue. Neuroradiol J 2007; 20: 656–61. doi: 10.1177/197140090702000609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heilbrun MP, Jorgensen PB, Boysen G. Relationships between cerebral perfusion pressure and regional cerebral blood flow in patients with severe neurological disorders. Stroke 1972; 3: 181–95. doi: 10.1161/01.str.3.2.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.