Abstract

In this study, a set of novel benzoxazole derivatives were designed, synthesised, and biologically evaluated as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors. Five compounds (12d, 12f, 12i, 12l, and 13a) displayed high growth inhibitory activities against HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines and were further investigated for their VEGFR-2 inhibitory activities. The most potent anti-proliferative member 12 l (IC50 = 10.50 μM and 15.21 μM against HepG2 and MCF-7, respectively) had the most promising VEGFR-2 inhibitory activity (IC50 = 97.38 nM). A further biological evaluation revealed that compound 12l could arrest the HepG2 cell growth mainly at the Pre-G1 and G1 phases. Furthermore, compound 12l could induce apoptosis in HepG2 cells by 35.13%. likely, compound 12l exhibited a significant elevation in caspase-3 level (2.98-fold) and BAX (3.40-fold), and a significant reduction in Bcl-2 level (2.12-fold). Finally, docking studies indicated that 12l exhibited interactions with the key amino acids in a similar way to sorafenib.

Keywords: Anticancer, cell cycle, apoptosis, benzoxazole, VEGFR-2

1. Introduction

Cancer chemotherapy has been considered one of the most important medical advances in the past few decades1. However, the narrow therapeutic index besides the unpredictable effects were the major drawbacks of the primary introduced drugs2. In contrast, the recently developed targeted therapies gained the advantages of interfering with specific molecular targets almost located in the tumour cells with minimised effect on the normal cells3. Thus, these agents provide a high specific therapeutic window with limited non-specific toxicities.

Among the major vital cancer drug targets are tyrosine kinases (TKs) because of their potential role in the modulation of growth factor signalling4,5. Upon their activation, TKs increase both proliferation and growth of tumour cells with induction of apoptosis and reinforcement of angiogenesis and metastasis6. Thus, TKs inhibition by different inhibitors became a key approach in cancer management7. The evidenced drug ability as well as the safety profile of the FDA-approved TKs inhibitors emphasised the attractiveness of TKs as drug targets.

Owing to their significant participation in modulating angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) have been considered the key players over other TKs8. VEGFs action is performed after their binding to three different tyrosine kinase (TK) receptors, namely, VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-38. VEGFR-2 receptor possesses the most crucial role among the rest subtypes as its activation leads to initiation of downstream signal transduction pathway via dimerisation followed by autophosphorylation of tyrosine receptor, a pathway resulting finally to angiogenesis9. Therefore, hindering VEGF/VEGFR-2 pathway or, even, weakening its response is of considered targets of the recent chemotherapeutic agents10. Despite a large number of small molecules with various chemical scaffolds being evidenced to tackle this pathway, resistance development in addition to different adverse effects still the main drawback of the current known VEGFR-2 inhibitors drugs11. Thus, the discovery of more effective and less dangerous VEGFR-2 inhibitors becomes an attractive therapeutic target for cancer drug discovery12. It has been discovered that VEGFR-2 inhibition in cancer cells causes and expedites apoptosis, which works in concert to enhance the antitumor effect. Hence, the most potent derivative has thoroughly discoursed in our work through the assessment of certain apoptotic markers such as caspase-3 (a crucial component in apoptosis that coordinates the destruction of cellular structures such as DNA and cytoskeletal proteins13, BAX and Bcl-2 (members of the Bcl-2 family and core regulators of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis)14.

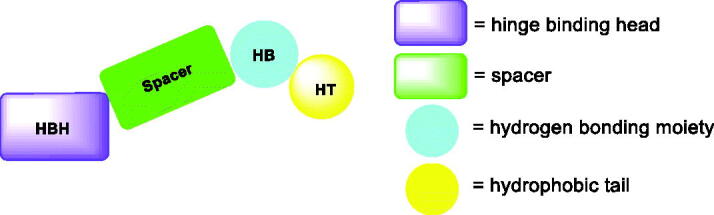

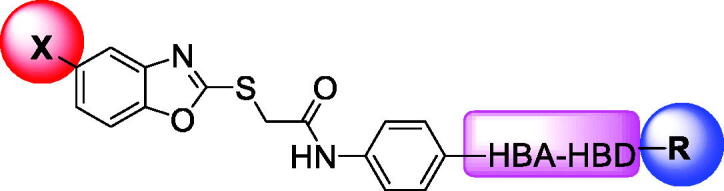

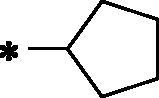

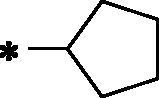

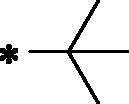

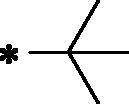

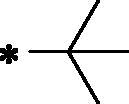

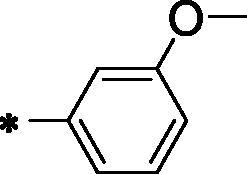

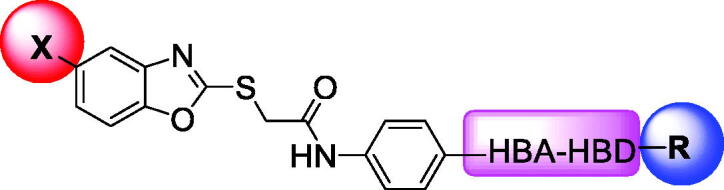

Over the last decade, we have built a project that is concerned with cancer management. Our high-throughput efforts gave us the opportunity to identify several small molecules that may serve as anti-angiogenic agents9. Most of these molecules exhibited VEGFR-2 inhibitory activity comparable to that of the FDA-approved inhibitor, sorafenib. These molecules were precisely designed to resemble the four main structural parts of sorafenib and other VEGFR-2 inhibitors15–17. Those parts were well-known to be a hydrophobic hinge binding head, a linker, a hydrogen-bonding moiety, and a hydrophobic tail (Figure 1). These previously mentioned parts enabled the designed compounds to fit perfectly in the TK active pocket. Based on the promising biological results in our former published work in which we utilised benzoxazole moieties as a hinge-binding core18, we decided to continue our preliminary VEGFR-2 studies using the same three different scaffolds of benzoxazole but with two main considerable additional modifications; a) For the allosteric hydrophobic pocket, we used different terminal aliphatic hydrophobic moieties including cyclopentyl (compounds 12a-c) and ter-butyl moiety (compounds 12d-f). This allowed us to make a comparative study between aliphatic and aromatic derivatives of each scaffold and study the SAR of the obtained compounds as anticancer leads with significant VEGFR-2 inhibitory potentialities, as was planned in our design. b) The pharmacophore moiety was selected to be amide derivative (compounds 12a-l) or diamide derivatives (compounds 13a-c) to study which derivative is more preferred biologically.

Figure 1.

The four main pharmacophoric requirements of VEGFR-2 inhibitors.

1.1. Rationale and design

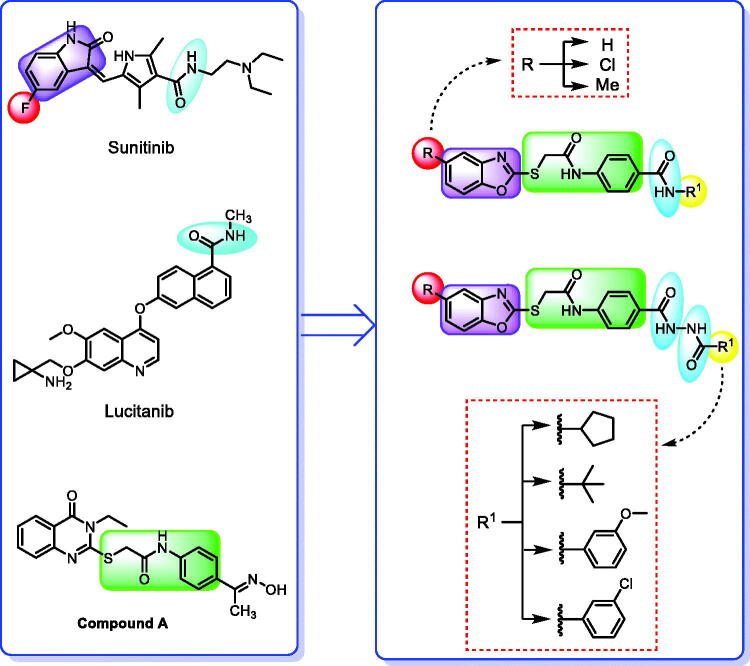

Forcing by the fact that molecular hybridisation is one of the most important drug discovery approaches, our team co-workers started the present work. Sunitinib, a multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor19, lucitanib, a dual VEGFRs and FGFRs inhibitor20, and compound A, a potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor were our guides for building a new anti-angiogenic hybrid21. Thus, the indolinylidene moiety of sunitinib was altered to be benzoxazole in the new hybrid to investigate its ability to modify the biological effects. In addition, we did another modification to the sunitinib structure via replacing the fluorine atom by either hydrogen, methyl, or chlorine atoms that allowed us to measure the biological effects of these atoms compared to the fluorine atom. In contrast, the carboxamide moiety of both sunitinib and lucitanib was kept or expanded to continue acting as a hydrogen bonding part. On the other side, the hydrophobic tail in the new hybrid was suggested to be either aliphatic (tert-butyl), alicyclic (cyclopentyl), or aromatic (methoxy or chloro phenyl) to get a diverse number of congeners with a higher chance to study the structure-activity relationship of the newly designed hybrid. However, an in silico study was also carried out through the docking tools to confirm the proposed design (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of the suggested rationale.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

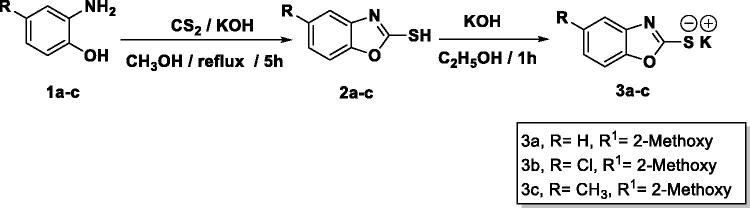

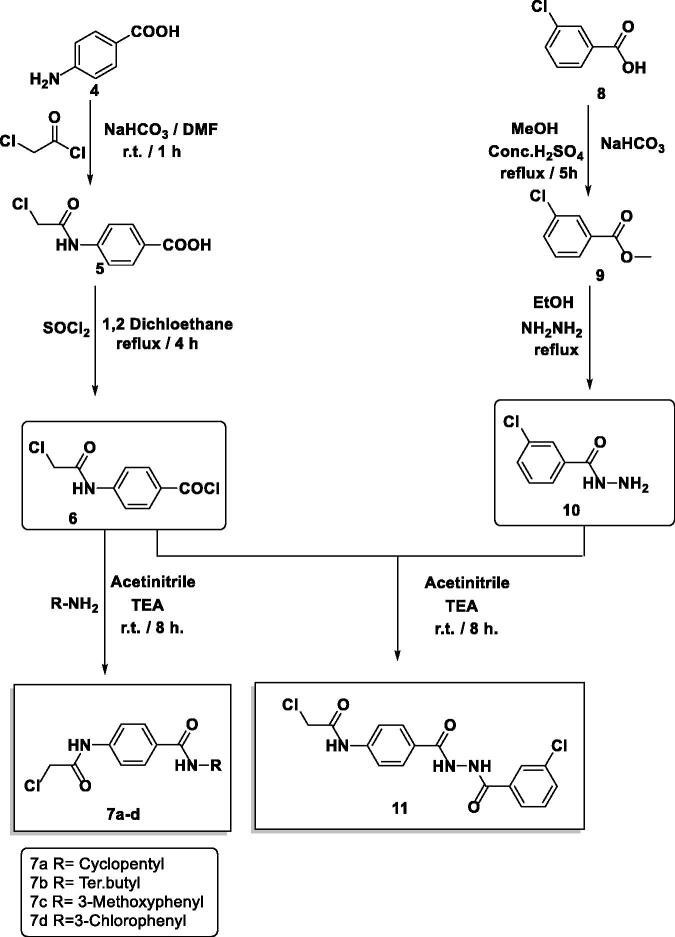

The final benzoxazoles 12a-l and 13a-c were synthesised as presented in Schemes 1–3. The starting materials and key intermediates 2a-c, 3a-c, 5, 6, 7a-d, 9, 10, and 11 were primarily prepared according to the reported methods22–25 as delineated in Schemes 1 and 2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the starting materials 3a-c.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the intermediates 7a-d and 11.

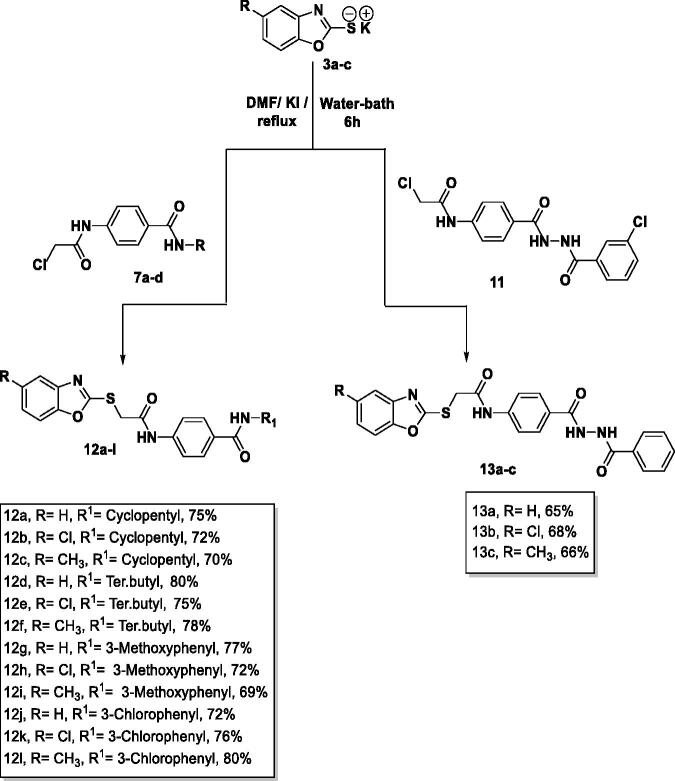

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the final compounds 12a-l and 13a-c.

The final target candidates 12a-l and 13a-c were furnished in dry DMF via heating the potassium salts 3a-c with the previously synthesised intermediates 7a-d and 11, respectively (Scheme 3). Infra-red (IR) spectra of compounds 12a-l indicated the presence of characteristic NH and C = O groups stretching bands at a range of 3181–3412 and 1644–1688 cm−1, respectively. Moreover, their 1H NMR spectra showed the presence of the two NH amide group signals at a range of δ 7.73–10.83 ppm. The formation of compounds 13a-c was confirmed by 1H NMR spectra which showed the appearance of three singlet signals at a range of δ 10.53–10.79 ppm corresponding to the NH protons.

2.2. Biological evaluation

2.2.1. In-vitro antiproliferative activities against MCF-7 and HepG2 cell lines

The in vitro antiproliferative effects of the newly synthesised benzoxazole derivatives 12a-l and 13a-c were determined against hepatocellular cancer (HepG2) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines employing the standard MTT assay protocol wherein sorafenib was applied as a reference. The cytotoxicity results were obtained as median growth inhibitory concentration (IC50). As presented in Table 1, major members of the synthesised compounds displayed promising anticancer activity.

Table 1.

In vitro anti-proliferative effects of the obtained compounds against HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines.

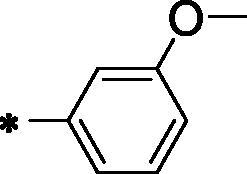

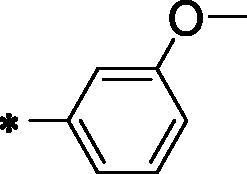

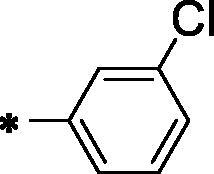

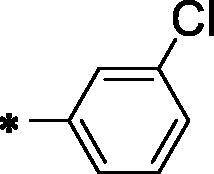

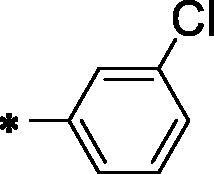

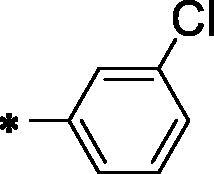

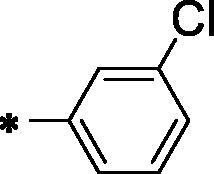

| Comp. No. | X | HBA-HBD | R |

In vitro IC50 (µM) a |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2 | MCF-7 | ||||

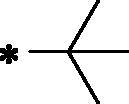

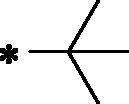

| 12a | H | -NH-CO- |

|

38.83 ± 3.2 | 33.27 ± 2.9 |

| 12b | Cl | -NH-CO- |

|

64.16 ± 6.1 | 77.03 ± 7.3 |

| 12c | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

74.30 ± 6.8 | 36.72 ± 3.3 |

| 12d | H | -NH-CO- |

|

23.61 ± 2.1 | 44.09 ± 3.8 |

| 12e | Cl | -NH-CO- |

|

71.59 ± 6.7 | 62.29 ± 5.8 |

| 12f | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

36.96 ± 3.4 | 22.54 ± 1.8 |

| 12g | H | -NH-CO- |

|

36.67 ± 2.9 | 53.01 ± 5.1 |

| 12h | Cl | -NH-CO- |

|

102.10 ± 8.5 | 85.62 ± 8.2 |

| 12i | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

27.30 ± 2.2 | 27.99 ± 2.1 |

| 12j | H | -NH-CO- |

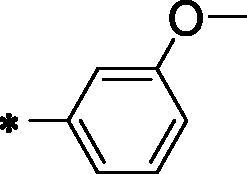

|

50.92 ± 4.6 | 33.61 ± 2.8 |

| 12k | Cl | -NH-CO- |

|

28.36 ± 2.5 | 86.62 ± 7.8 |

| 12l | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

10.50 ± 0.8 | 15.21 ± 1.1 |

| 13a | H | -CO -NH-NH-CO- |

|

25.47 ± 2.1 | 32.47 ± 2.9 |

| 13b | Cl | -CO -NH-NH-CO- |

|

42.06 ± 3.8 | 26.31 ± 2.2 |

| 13c | CH3 | -CO -NH-NH-CO- |

|

24.25 ± 2.1 | 53.13 ± 3.7 |

| Sorafenib | - | - | - | 5.57 ± 0.4 | 6.46 ± 0.3 |

aData are presented as mean of the IC50 values from three different experiments.

Observing the results of anti-proliferative activity, valuable data concerning the structure-activity relationships was determined. In general, the 5-methylbenzo[d]oxazole containing derivatives (compounds 12c, 12f, 12i, 12 l, and 13c) (IC50 values ranging from 10.50 to 74.30 μM) were more active than the unsubstituted benzo[d]oxazole derivatives (compounds 12a, 12d, 12 g, 12j, and 13a) (IC50 values ranging from 25.47 to 53.01 μM). In the meantime, the 5-chlorobenzo[d]oxazole derivatives (compounds 12b, 12e, 12h, 12k, and 13b) (IC50 values ranging from 26.31 to 102.10 μM) exhibited less potent activities.

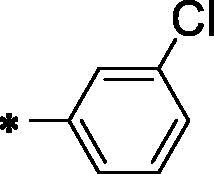

A closer look to the results indicated that compound 12l achieved the most potent anticancer activity against HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values of 10.50 μM and 15.21 μM, respectively, compared to sorafenib with IC50 value of 5.57 μM and 6.46 μM against HepG2 and MCF-7, respectively. This indicated that hybridisation of 5-methylbenzo[d]oxazole with terminal 3-chlorophenyl moiety potentiates the anticancer activity against HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines. Moreover, compounds 12d (IC50 = 23.61 and 44.09 µM), 12f (IC50 = 36.96 and 22.54 µM), 12i and (IC50 = 27.30 and 27.99 µM) exhibited promising activities against HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines, respectively.

Initially, the effect of a hydrogen-bonding moiety on cytotoxic activities has been explored. Regarding the unsubstituted benzo[d]oxazole derivatives, it was noticed that the diamide derivative 13a (IC50 = 25.47 and 32.47 µM against HepG2 and MCF-7, respectively) displayed better effects than the corresponding amide derivative 12j (IC50 = 50.92 and 33.61 µM against MCF-7 and HepG2, respectively). Conversely, in 5-methylbenzo[d]oxazole derivatives, the decreased IC50 value of the amide derivative 12l (IC50 = 10.50 μM and 15.21 μM against HepG2 and MCF-7, respectively) in comparison to the corresponding diamide member of the same scaffold 13c (IC50 = 24.25 and 53.13 μM) indicated that the amide derivatives more preferred biologically than the corresponding diamide derivatives.

We then investigated the impact of the terminal hydrophobic tail on the in-vitro antiproliferative activities. Concerning the unsubstituted benzo[d]oxazole derivatives, compound 12d, containing terminal tert-butyl moiety displayed the highest inhibitory activity against the HepG2 cell line with an IC50 value of 23.61 μM while 13a, containing terminal 3-chlorophenyl moiety exhibited the lowest IC50 value (32.47 µM) against MCF-7 cell line. On the other hand, among 5-chlorobenzo[d]oxazole-based derivatives, the amide member bearing terminal 3-chlorophenyl arm 12k displayed the most potent in-vitro antiproliferative activities against the HepG2 cell line with an IC50 value of 28.36 μM. In the meantime, the diamide member 13 b, bearing the same terminal arm presented the most promising activity against MCF-7 cell line with IC50 value of 26.31 μM.

2.2.2. Vegfr-2 inhibitory assay

VEGFR-2 inhibitory effect of the most cytotoxic candidates 12d, 12f, 12i, 12 l, and 13a was investigated and summarised in Table 2. Sorafenib was used as a reference.

Table 2.

IC50 values of the tested compounds on the inhibitory activities against VEGFR-2 Kinases Assay.

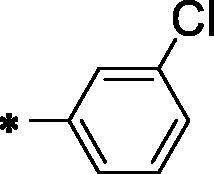

| Comp. No. | X | HBA-HBD | R | VEGFR-2, IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12d | H | -NH-CO- |

|

194.60 |

| 12f | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

264.90 |

| 12i | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

155.00 |

| 12l | CH3 | -NH-CO- |

|

97.38 |

| 13a | H | -CO -NH-NH-CO- |

|

267.80 |

| Sorafenib | - | - | - | 48.16 |

Matching with the cytotoxicity results, compound 12l, the most cytotoxic member, displayed the strongest VEGFR-2 inhibitory effect (IC50 = 97.38 nM) comparing sorafenib (IC50 = 48.16 nM). Additionally, compounds 12d and 12i showed moderate VEGFR-2 inhibitory effects with the concentrations of 194.6 and 155 nM, respectively. Unlikely, compounds 12f and 13a showed weak VEGFR-2 effects with the concentration of 264.90 and 267.80 nM, respectively.

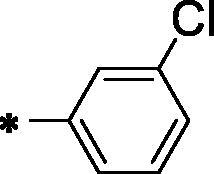

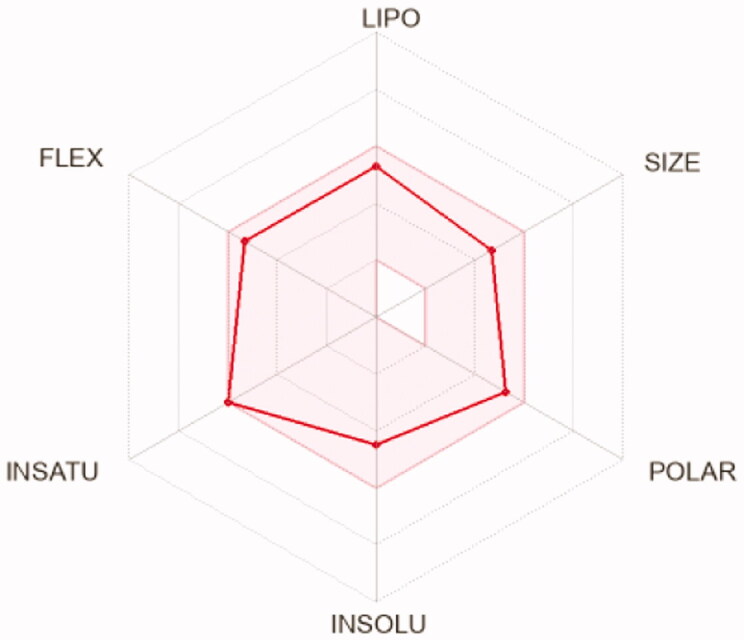

2.2.3. Correlation study between cytotoxicity and VEGFR-2 inhibition

The VEGFR-2 inhibitory activities of the tested compounds were plotted against their corresponding cytotoxicity in a simple linear regression for the HepG2 cell line in order to confirm the relationship between VEGFR-2 inhibition and cytotoxicity. The calculated R2 square value 0.6274) shows a significant correlation between the tested compounds' induction of cytotoxicity and inhibition of VEGFR-2. As a result, one possible mechanism of the established compounds' cytotoxicity in the established cell line is their inhibition of VEGFR-2 activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation graph study.

2.2.4. Evaluation of in vitro cytotoxicity against normal cell line

The most potent members 12d, 12i, and 12l were assessed for their in vitro cytotoxicity against normal cell lines using WI-38 (a human lung cell line) and sorafenib as a reference The IC50 values for compounds 12d, 12i, and 12l were 99.41, 76.78, and 37.97 M, respectively (Table 3). Such values were very high in comparison to the corresponding values on cancer cell lines, which reflect high safety profile of the tested candidates towards normal cell lines.

Table 3.

IC50 results of 12d, 12i, and 12 l against WI-38 cell line.

| Compound | WI-38, IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|

| 12d | 99.41 |

| 12i | 76.78 |

| 12l | 37.79 |

| Sorafenib | 22.10 |

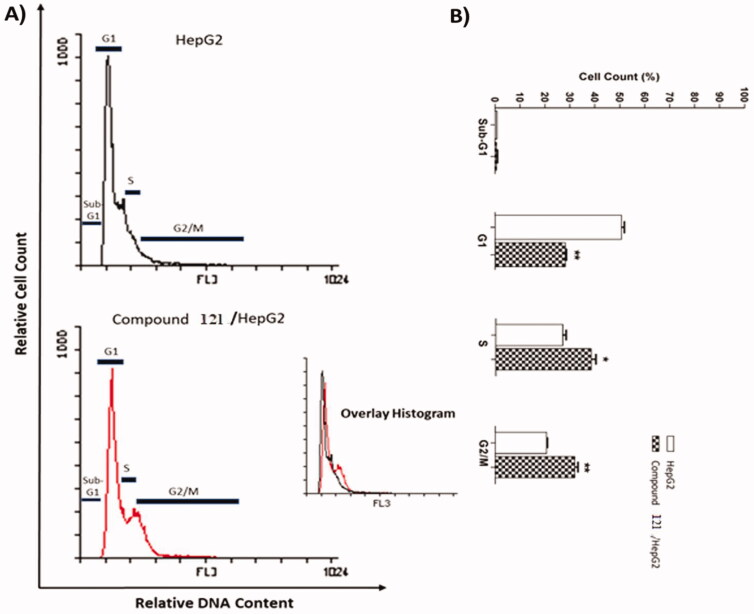

2.2.5. Cell cycle analysis

Compound 12I, achieved notable cytotoxic and VEGFR-2 inhibitory potencies was further studied mechanistically for cell cycle progression and induction of apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Cell cycle process was analysed after exposure of HepG2 cells to 12I with a concentration of 10.50 µM for 24 h. Flow cytometry data revealed that the percentage of cells arrested at Pre-G1 phase decreased from 0.93% (in control cells) to 0.79% (in 12I) treated cells. Additionally, a marked decrease in cell population was observed at the G1 phase (28.34%) comparing to control cells (51.07%). For the S phase compound 12l induced a significant increase in the cell population (38.68%) comparing to control cells (27.22%). Finally, compound 12I exhibited significant increase in the cell population (32.10%) at the G2/M phase, comparing to the control cells (20.78%). Such outputs verify that compound 12I arrested the HepG2 cancer cell’s growth mainly at the Pre-G1 and G1 phases (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Table 4.

Supressing potentialities of 12I on the cell cycle of HepG2 cells after 24 h treatment.

| Sample | Cell cycle distribution (%)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %Sub-G1 | %G1 | %S | % G2/M | |

| HepG2 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 51.07 ± 1.03 | 27.22 ± 1.24 | 20.78 ± 0.23 |

| Compound 12 l /HepG2 | 0.79 ± 0.25 | 28.43 ± 0.37** | 38.68 ± 1.81* | 32.10 ± 181** |

aValues are given as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments and *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of HepG2 cell cycle after the treatment of compound 12 l.

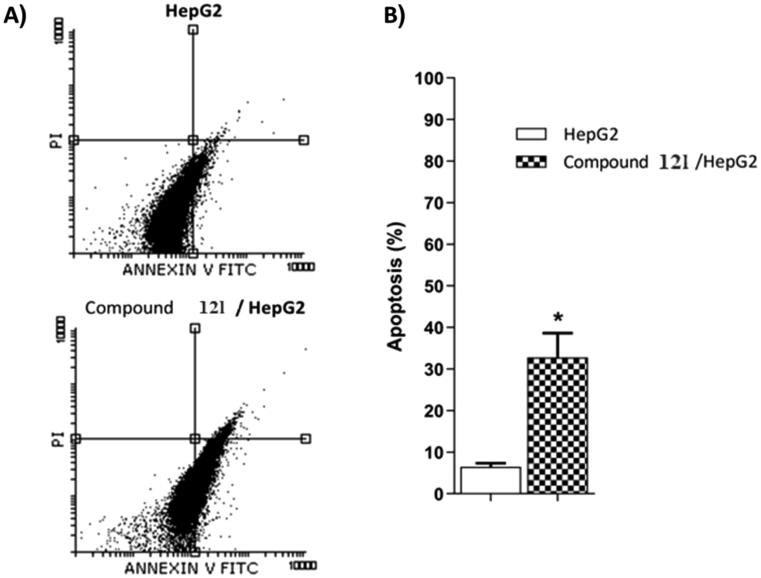

2.2.6. Apoptosis analysis

The most potent anticancer agent 12l was selected for the assessment of apoptosis in HepG2 cells using Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) double staining assay method. In this method, HepG2 cells were incubated with compound 12l at the IC50 concentration (10.50 µM) for 24 h. The results revealed that compounds 12l could induce apoptosis more than the untreated control cells by a ratio of 35.13%. In details, 32.45 and 2.86% for early and late apoptotic phases, respectively compared to control, (6.56%,5.34%,1.22%, respectively) (Figure 5 and Table 5).

Figure 5.

Flow cytometry analysis of compound 12 l apoptotic induction against HepG2 cells.

Table 5.

Apoptotic potentialities compound 12 l against HepG2 cells after 24 h treatment.

| Sample |

Viable a (Left Bottom) |

Apoptosis a |

Necrosis a (Left Top) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Early (Right Bottom) |

Late (Right Top) |

|||

| HepG2 | 92.96 ± 0.55 | 5.34 ± 0.01 | 1.22 ± 0.77 | 0.48 ± 0.27 |

| 12l / HepG2 | 64.55 ± 3.43 | 32.45 ± 3.13* | 2.86 ± 0.21 | 0.14 ± 0.06 |

aValues are given as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05.

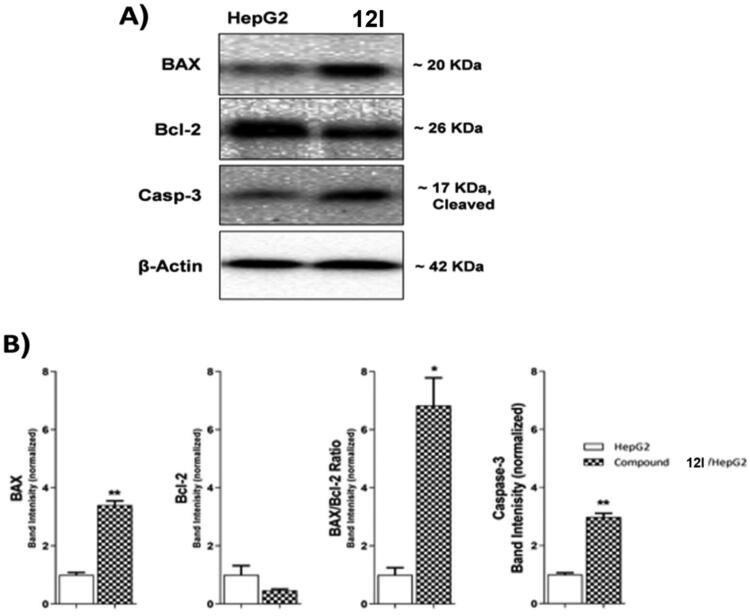

2.2.7. Evaluation of BAX and bcl-2 expressions

Compound 12lwas subjected to further cellular mechanistic study. The cellular levels of BAX and Bcl-2 were measured using the western blot technique after compound 12l was applied to HepG2 cells for 24 h. The results indicated that compound 12l increased the concentration of the pro-apoptotic factor BAX by 3.40-fold while decreasing the concentration of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 by 2.12-fold. Furthermore, a significant increase in the BAX/Bcl-2 ratio by 6.83-fold was observed. The obtained findings indicated that compound 12l was effective in the apoptosis cascade and may encourage the apoptotic pathway (Table 6 and Figure 6).

Table 6.

Effect of compound 12 l on the levels of BAX, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3 proteins expression in HepG2 cells treated for 24 h.

| Sample | Protein expression (normalized to β-actin) a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAX | Bcl-2 | BAX/Bcl-2 ratio | Caspase-3 | |

| HepG2 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.32 | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 1.00 ± 0.06 |

| 12l | 3.40 ± 0.15** | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 6.83 ± 0.96* | 2.98 ± 0.13** |

aValues are given as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

The immunoblotting of effect of compound 12 l against BAX, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3.

2.2.8. Caspase 3 assay

Caspase-3 has a key role in apoptosis initiation and execution26,27. The western blot technique was used to investigate the effect of compound 12 l, the most promising member, on the caspase-3 level. HepG2 cells were treated with 12l (10.50 µM) for 24 h. Comparing control HepG2 cells, compound 12l caused a significant increase in the cellular levels of caspase-3 (2.98-fold) as presented in Table 6 and Figure 6.

2.3. In silico studies

2.31.1. Docking study

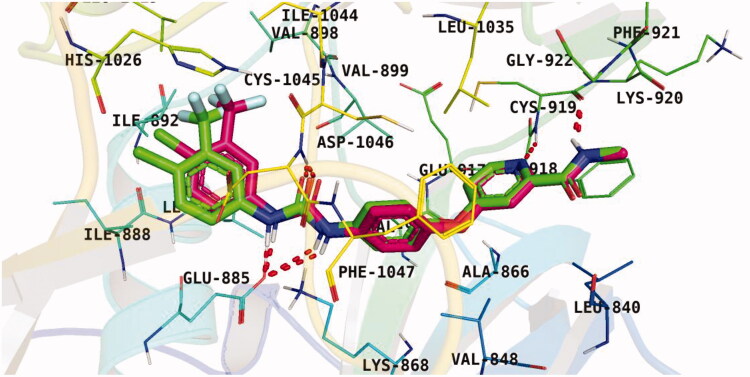

To understand the pattern by which the synthesised compounds bound to the active site28,29, all compounds were subjected to a docking study into the VEGFR-2 ATP binding site (PDB: 4ASD, resolution: 2.03 Å). The native co-crystallized inhibitor, sorafenib, was adopted as a reference in the present work. Following the preparation of the downloaded protein, a validation step was carried out in which the native inhibitor, sorafenib, was re-docked against the catalytic VEGFR-2 site. Results of the previous step successfully reproduced an identical binding pattern to that of the co-crystallized ligand with an RMSD value of 0.71 Å Figure 7. Thus, the later findings supported the validity of the suggested docking protocol.

Figure 7.

Results of the re-docking step into the VEGFR-2 catalytic site; native ligand (green) and the obtained pose (red).

Observation of the kinds of interaction between sorafenib and the VEGFR-2 catalytic site revealed that it could form two interaction types (Figure 8). The 1st type is an H-bonding interaction, as sorafenib formed two H-bonds with a critical amino acid (Cys919) in the hinge region in addition to three H-bonds with the DFG motif amino acids (Asp1046 and Glu885). The 2nd interaction type included different π interactions between sorafenib and the hydrophobic amino acids among the active pocket.

Figure 8.

Sorafenib binding interactions with VEGFR-2 catalytic site.

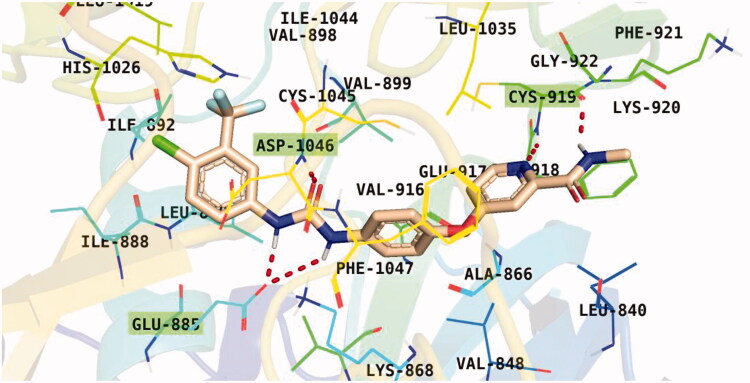

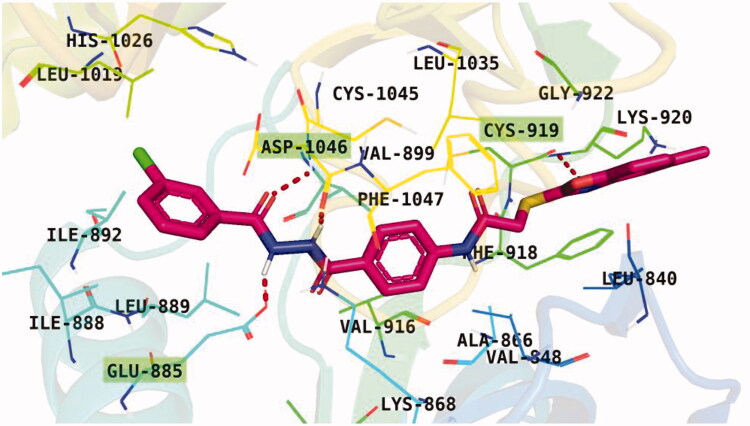

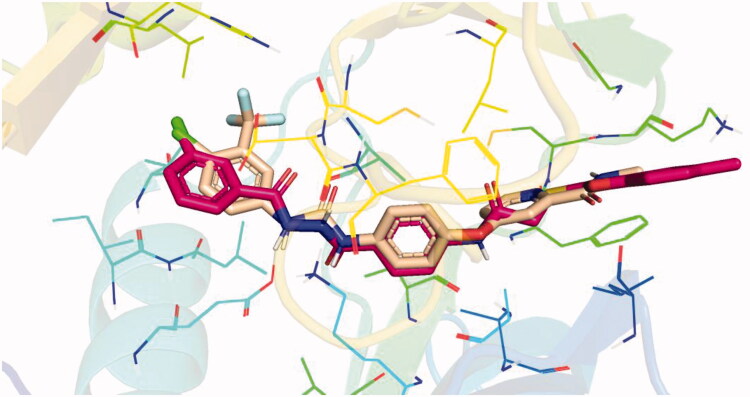

Docking conformations of the synthesised derivatives revealed that they were stacked onto the VEGFR-2 catalytic site in a way similar to that of the original ligand. However, the predicted docking pose of compound 12l showed that its benzoxazole fragment was linked to the hinge region Cys919 amino acid via a strong H-bond. Additionally, compound 12l interacted by an H-bond with Glu885 and two H-bonds with Asp1046 in the DFG motif (Figure 9). The later binding pattern gave a reasonable explanation for 12l of being the most active biologically among the tested compounds. A superimposition poses of 12l and the native ligand, sorafenib, provided additional evidence to the obtained results. As presented in Figure 10, compound 12l and sorafenib generally overlapped well and had the same 3-D orientation. Niceties revealed that the pharmacophoric moieties of sorafenib represented by N-methylpicolinamide, phenoxy, urea, and 4-chloro-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) moieties had the same orientation with the 5-methylbenzo[d]oxazol, N-phenylacetamide, amide, and 3-chlorophenyl moieties, respectively of compound 12l.

Figure 9.

Binding pose of 12 l with the active site of VEGFR-2.

Figure 10.

Superimposition of 12 l (red) and sorafenib (wheat) inside the VEGFR-2 catalytic site.

2.3.2. Pharmacokinetic profiling study

In the current study, an in silico computational study of the tested candidates was conducted following the directions of Veber’s and Lipinski’s rule of five30,31.

The obtained findings presented in Table 7 showed that all tested compounds showed no contravention of Lipinski’s and Veber’s Rules and hence display a drug-like molecular nature. In detail, the LogP, molecular weight, number of H-bond donors, and number of H-bond acceptors of these fifteen compounds are within the accepted values of less than 5, 500, 5, and 10, respectively. Moreover, the number of rateable bonds and TPSA of such compounds are within the acceptable values of less than 10 and 140 Å2, respectively.

Table 7.

Physicochemical properties of the tested compounds passed Lipinski and Veber Rules

| Comp. | Lipinski Rules |

Veber Rules

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num HD | Num HA | M Wt | AlogP | Num Rotatable Bonds | TPSA | |

| 12a | 2 | 4 | 395.475 | 3.685 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12b | 2 | 4 | 429.92 | 4.35 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12c | 2 | 4 | 409.501 | 4.171 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12d | 2 | 4 | 383.464 | 3.214 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12e | 2 | 4 | 417.909 | 3.879 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12f | 2 | 4 | 397.491 | 3.701 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12g | 2 | 5 | 433.48 | 3.843 | 7 | 118.76 |

| 12h | 2 | 5 | 467.925 | 4.508 | 7 | 118.76 |

| 12i | 2 | 5 | 447.506 | 4.33 | 7 | 118.76 |

| 12j | 2 | 4 | 437.899 | 4.524 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12k | 2 | 4 | 472.344 | 5.189 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 12l | 2 | 4 | 451.925 | 5.01 | 6 | 109.53 |

| 13a | 3 | 5 | 446.478 | 3.117 | 7 | 138.63 |

| 13b | 3 | 5 | 480.923 | 3.781 | 7 | 138.63 |

| 13c | 3 | 5 | 460.505 | 3.603 | 7 | 138.63 |

2.3.3. Swissadme study

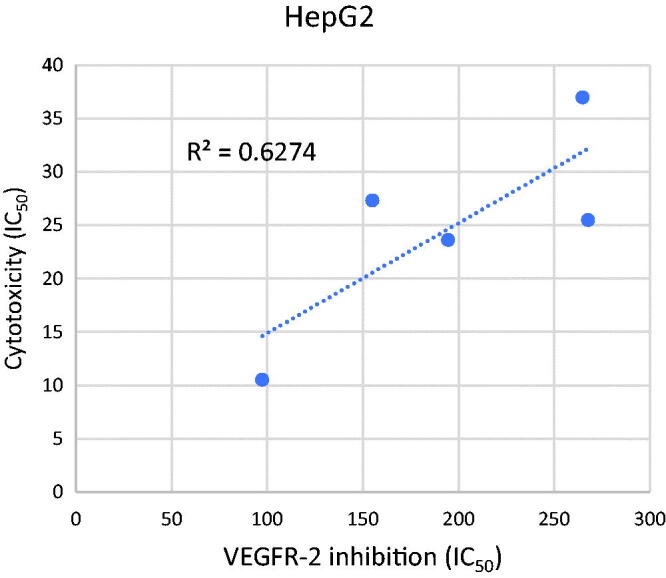

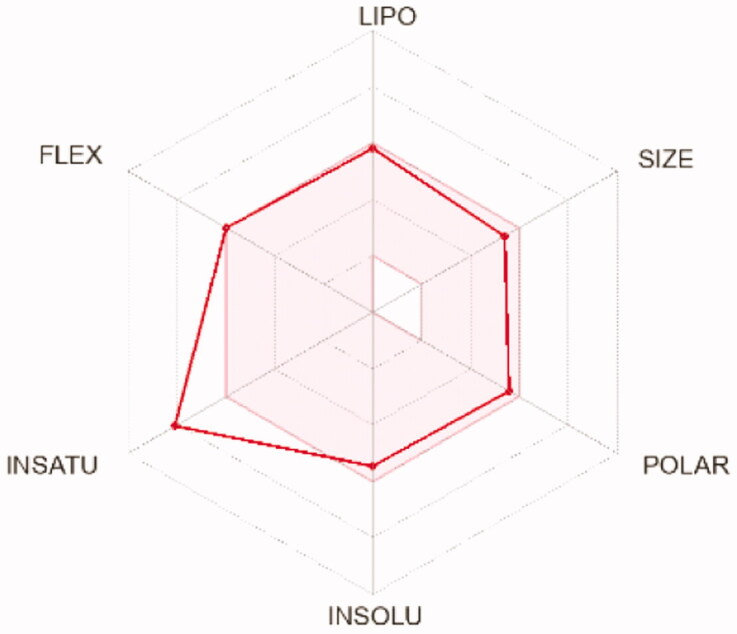

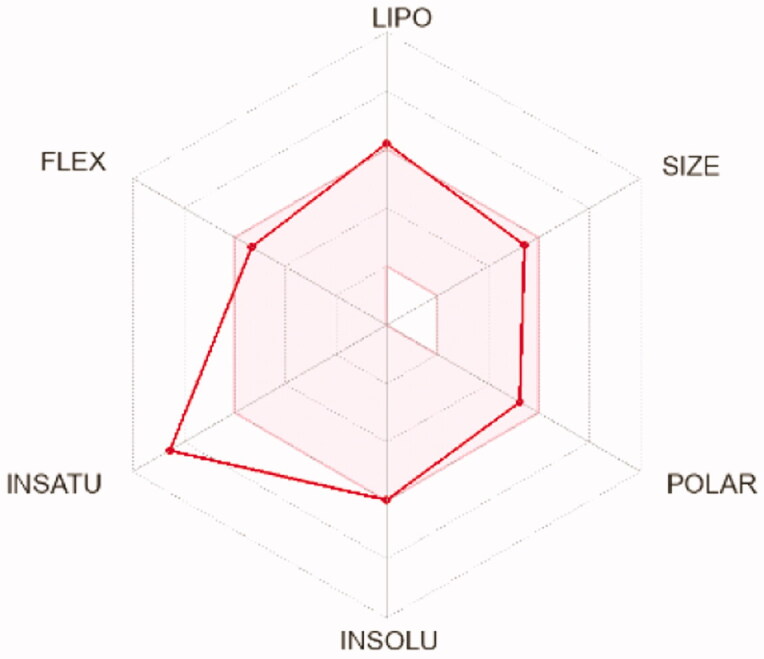

To compute the physicochemical properties and the drug likeness properties of the most potent compounds 12d, 12i, and 12 l, SwissADME online web tool was applied. The obtained results predicted that the physicochemical properties of the three candidates were in acceptable ranges, hence they may have good oral bioavailability. Also, they are expected to hve undesirable effects on CNS as they cannot pass BBB (Table 8). Furthermore, SwissADME revealed that compounds 12d, 12i, and 12l fulfilled Lipinskìs, Veber’s, and Ghose’s rules predicting that these compounds have promising drug-likeness profiles (Table 7). Moreover, the radar charts which involved the calculation of six parameters including lipophilicity, polarity, flexibility, size, saturation, and solubility showed that compounds 15 b and 17 b (represented by red lines and integrated into the pink area) are almost predicting acceptable oral bioavailability (Table 9).

Table 8.

ADME profile of compounds 12d, 12i, and 12 l

| Parameter | 12d | 12i | 12l |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical properties | |||

| Molecular weight | 383.46 | 447.51 | 451.93 |

| Num. heavy atoms | 27 | 32 | 31 |

| Num. H-bond acceptors | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Num. H-bond donors | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Molar Refractivity | 107.02 | 125.24 | 123.75 |

| TPSA | 109.53 Ų | 118.76 Ų | 109.53 Ų |

| Consensus Log Po/w | 3.34 | 3.98 | 4.48 |

| Log S (ESOL) | Moderately soluble | Moderately soluble | Moderately soluble |

| Drug likeness | |||

| Lipinski violations | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 0 violation |

| Ghose violations | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Veber violations | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Pharmacokinetics | |||

| GI absorption | High | Low | Low |

| BBB permeant | No | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 9.

Radar charts for prediction of oral bioavailability profile of compounds 12d, 12i, and 12 l

| Compounds | 12d | 12i | 12l |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radar images |

|

|

|

3. Conclusion

In the present study, fifteen benzoxazole derivatives were designed, synthesised as potential anticancer and VEGFR-2 inhibitors. The anticancer potentialities of the obtained derivatives were estimated against HepG2, and MCF-7 cell lines cell lines. Five compounds 12d (IC50 = 23.61 & 44.09 µM), 12f (IC50 = 36.96 & 22.54 µM), 12i (IC50 = 27.30 & 27.99 µM), compounds 12d (IC50 = 23.61 & 44.09 µM), 12f (IC50 = 36.96 & 22.54 µM), 12i (IC50 = 27.30 & 27.99 µM), and 13a (IC50 = 11.4 & 14.2 µM) displayed noticeable anticancer activities against HepG2 and MCF-7, respectively. Moreover, VEGFR-2 kinase inhibition assay results revealed that compound 12l showed the most potent inhibitory activity against VEGFR-2, comparing the reference drug, sorafenib. Owing to its notable high antiproliferative and VEGFR-2 inhibitory activities, derivative 12l was selected for further evaluation to understand its mechanistic studies. Cell cycle analysis indicated that 12l could arrest the malignant HepG2cells at the Pre-G1 and G1 phases and induced apoptosis by 35.13%, compared to 6.56% in the control cells. Additionally, compound 12l exhibited significant potential to increase caspase 3 (BAX and BAX/Bcl-2 ratio with (2.98, 3.40- and 6.83 folds, respectively). Similarly, it decreased Bcl-2 (2.12-fold) comparing the untreated cells. Molecular docking studies were accomplished for all the target derivatives. Docking findings supported biological activity results where the most potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor was able to incorporate the tyrosine kinase domain of VEGFR-2 in a fashion comparable to that of the well-known VEGFR-2 inhibitor, sorafenib.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

In Supplementary data, all apparatus used in the analysis of produced chemicals were elucidated. Compounds 2a-c, 3a-c, 6, 7a-c, 9, 10, and 11 were synthesised using procedures that have previously been reported32. The 1H/13C NMR analyses were carried out at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively in DMSO-d6 as a solvent. The chemical shifts were presented as ppm. The infra-red investigations were carried out using KBr disc and the results were presented as cm−1. The colours and meting points of the final compounds 12a-l and 13a-c were presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Colours, yields, and meting points of the target compounds

| Compounds | Color | Meting points (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| 12a | White crystals | 230–232 |

| 12b | White crystals | 240–242 |

| 12c | White crystals | 235–237 |

| 12d | White crystals | 211–215 |

| 12e | White crystals | 233–235 |

| 12f | White crystals | 222–224 |

| 12g | White crystals | 252–254 |

| 12h | White crystals | 244–246 |

| 12i | White crystals | 255–257 |

| 12j | White crystals | 240–242 |

| 12k | White crystals | 220–222 |

| 12l | White crystals | 266–268 |

| 13a | White crystals | 223–225 |

| 13b | White crystals | 211–213 |

| 13c | White crystals | 235–237 |

4.1.1. General procedure for preparation of the target compounds 12a-l

In 10 ml DMF containing 0.001 mol KI, 0.001 mol of 3a-c and 0.001 mol of the appropriate benzamide derivatives 7a-d were mixed and heated under reflux for 6 h. The reaction content was then poured on crushed ice. The collected crystals were filtered and crystalised from methanol to afford 12a-l.

4.1.1.1. 4–(2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-2-ylthio)acetamido)-N-cyclopentylbenzamide 12a

IR: 3495, 3383 (NH), 3054 (CH aromatic), 2951 (CH aliphatic), 1661, 1623 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.69 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.75–7.59 (m, 4H), 7.40–7.28 (m, J = 6.7, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 4.23 (h, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 1.89 (m, 2H), 1.79–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.59–1.50 (m, 4H); 13 C NMR: 165.81, 165.79, 164.32, 151.82, 141.68, 141.52, 128.74, 125.15, 124.83, 118.71, 110.69, 51.38, 37.26, 32.62, 24.10; MS (m/z) for C21H21N3O3S (395.48): 395.50 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.2. 4–(2-((5-Chlorobenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)-N-cyclopentylbenzamide 12b

IR: 3414, 3272 (NH), 3064 (CH aromatic), 2938 (CH aliphatic), 1656 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.68 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.76–7.63 (m, 4H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 4.22 (h, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 1.89 (m, 2H), 1.69 (m, 2H), 1.53 (m, 4H); 13 C NMR: 166.37, 165.93, 165.66, 150.58, 142.91, 141.44, 130.14, 129.48, 128.72, 124.80, 118.78, 118.46, 111.99, 51.40, 37.22, 32.57, 24.07.

4.1.1.3. N-Cyclopentyl-4–(2-((5-methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)benzamide 12c

IR: 3273 (NH), 3041 (CH aromatic), 2945 (CH aliphatic), 1657, 1618 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.68 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.16–7.09 (m, 1H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 4.23 (h, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.88 (m, 2H), 1.76–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.62–1.46 (m, 4H); 13 C NMR: 165.81, 164.17, 150.07, 141.70, 134.54, 130.16, 129.46, 125.60, 118.66, 110.04, 51.38, 37.26, 32.62, 24.10, 21.38; MS (m/z) for C22H23N3O3S (409.50): 409.48 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.4. 4–(2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-2-ylthio)acetamido)-N-(tert-butyl)benzamide 12d

IR: 3377, 3272 (NH), 3038 (CH aromatic), 2971 (CH aliphatic), 1613 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.68 (s, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.75 − 7.57 (m, 5H), 7.39–7.27 (m, 2H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 1.38 (s, 9H); MS (m/z) for C20H21N3O3S (383.47): 383.28 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.5. N-(Tert-butyl)-4–(2-((5-chlorobenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)benzamide 12e

IR: 3412, 3277 (NH), 3072 (CH aromatic), 2951 (CH aliphatic), 1655, 1604 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.70 (s, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.71–7.62 (m, 4H), 7.36 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 1.38 (s, 9H); 13 C NMR: 166.42, 166.08, 165.57, 150.60, 142.96, 141.32, 131.22, 129.46, 128.77, 124.74, 118.61, 118.48, 111.95, 51.17, 37.41, 29.10; MS (m/z) for C20H20ClN3O3S (417.91): 417.36 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.6. N-(Tert-butyl)-4–(2-((5-methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)benzamide 12f

IR: 3383, 3286 (NH), 3072 (CH aromatic), 2965 (CH aliphatic), 1709, 1626 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.66 (s, 1H), 7.88–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.72–7.58 (m, 3H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (s, 2H), 2.40 (s, 3H), 1.38 (s, 9H); MS (m/z) for C21H23N3O3S (397.49): 397.43 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.7. 4–(2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-2-ylthio)acetamido)-N-(3-methoxyphenyl)benzamide 12 g

IR: 3262 (NH), 3033 (CH aromatic), 2927 (CH aliphatic), 1647 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.83 (s, 1H), 10.17 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (p, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (t, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (s, 2H), 3.77 (s, 3H); 13 C NMR: 165.99, 165.32, 164.17, 159.89, 150.09, 141.88, 140.93, 134.58, 129.82, 129.23, 125.65, 118.86, 118.67, 113.01, 110.10, 106.48, 55.47, 21.40; MS (m/z) for C23H19N3O4S (433.48): 433.34 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.8. 4–(2-((5-Chlorobenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)-N-(3-methoxyphenyl)benzamide 12 h

IR: 3412, 3259 (NH), 3065 (CH aromatic), 2991, 2933 (CH aliphatic), 1656 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.80 (s, 1H), 10.15 (s, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.86–7.70 (m, 3H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 18.8, 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (s, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H); 13 C NMR: 166.42, 166.08, 165.57, 150.60, 142.96, 141.32, 131.22, 129.46, 128.77, 124.74, 118.61, 118.48, 111.95, 51.17, 29.10; MS (m/z) for C23H18ClN3O4S (467.92): 467.17 (M+, 40%), 345.36 (100%).

4.1.1.9. N-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-4–(2-((5-methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)benzamide 12i

IR: 3385, 3282 (NH), 3073 (CH aromatic), 2931 (CH aliphatic), 1688, 1648 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.79 (s, 1H), 10.15 (s, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.56–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 2.40 (s, 3H); 13 C NMR: 165.99, 165.32, 164.17, 159.89, 150.09, 142.14, 141.88, 140.93, 134.58, 130.11, 129.82, 129.23, 125.65, 118.86, 118.67, 113.01, 110.10, 109.50, 106.48, 55.47, 37.27, 21.40; MS (m/z) for C24H21N3O4S (447.51): 447.32 (M+, 100%).

4.1.1.10. 4–(2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-2-ylthio)acetamido)-N-(3-chlorophenyl)benzamide 12j

IR: 3384, 3276 (NH), 3066 (CH aromatic), 2981 (CH aliphatic), 1657 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.80 (s, 1H), 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.03–7.93 (m, 3H), 7.82–7.63 (m, 5H), 7.43–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.17 (td, J = 9.2, 8.1, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (d, J = 96.7 Hz, 2H); 13 C NMR: 166.00, 165.55, 164.30, 151.83, 142.34, 141.68, 141.23, 133.41, 130.75, 129.34, 124.85, 120.16, 118.92, 118.74, 110.72, 37.29. MS (m/z) for C22H16ClN3O3S (437.90): 437.33 (M+, 10%), 120.20 (100%).

4.1.1.11. 4–(2-((5-Chlorobenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)-N-(3-chlorophenyl)benzamide 12k

IR: 3379, 3265 (NH), 3093 (CH aromatic), 2980 (CH aliphatic), 1644 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.82 (s, 1H), 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.10–7.91 (m, 3H), 7.85–7.59 (m, 5H), 7.42–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (s, 2H); 13 C NMR: 166.39, 165.79, 165.52, 150.61, 142.96, 142.31, 141.24, 133.41, 130.70, 129.34, 124.73, 120.15, 118.91, 118.49, 111.94, 37.46; MS (m/z) for C22H15Cl2N3O3S (472.34): 472.70 (M+, 30%) 345.20 (100%).

4.1.1.12. N-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4–(2-((5-methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamido)benzamide 12 l

IR: 3384, 3181 (NH), 3034 (CH aromatic), 2970 (CH aliphatic), 1651 (C = O); 1H NMR 10.83 (s, 1H), 10.35 (s, 1H), 8.26–6.84 (m, 11H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 2.44 (s, 3H); MS (m/z) for C23H18ClN3O3S (451.93): 451.30 (M+, 100%).

4.1.2. General procedure for preparation of the target compounds 13a-c

In 10 ml DMF containing 0.001 mol KI, 0.001 mol of 3a-c and 0.001 mol of N-(4–(2-benzoylhydrazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-2-chloroacetamide 11, were mixed well and refluxed for 6 h. The reaction content was then poured on crushed ice. The collected crystals were filtered and crystalised from methanol to afford 13a-c.

4.1.2.1. 2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-2-ylthio)-N-(4–(2-(3-chlorobenzoyl)hydrazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)- acetamide 13a

IR: 3384, 3279 (NH), 3014 (CH aromatic), 2853 (CH aliphatic), 1660 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.79 (s, 1H), 10.65 (s, 1H), 10.53 (s, 1H), 8.06–7.85 (m, 4H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (q, J = 8.7, 8.2 Hz, 3H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.41–7.29 (m, 2H), 4.47 (s, 2H); MS (m/z) for C23H17ClN4O4S (480.92): 480.42 (M+, 10%), 311.23 (100%).

4.1.2.2. 2-((5-Chlorobenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)-N-(4–(2-(3-chlorobenzoyl)hydrazine-1-carbonyl)- phenyl)acetamide 13 b

IR: 3279, 3167 (NH), 3017 (CH aromatic), 2855 (CH aliphatic), 1656 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.79 (s, 1H), 10.65 (s, 1H), 10.53 (s, 1H), 8.10–7.85 (m, 4H), 7.81–7.72 (m, 3H), 7.69 (dd, J = 9.0, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (s, 2H); 13 C NMR: 166.39, 165.80, 165.04, 150.61, 142.96, 134.99, 133.87, 131.07, 129.48, 129.08, 127.75, 126.66, 124.76, 119.02, 118.51, 111.97, 37.44; MS (m/z) for C23H16Cl2N4O4S (515.37): 415.76 (M+, 10%), 345.24 (100%).

4.1.2.3. N-(4–(2-(3-Chlorobenzoyl)hydrazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-2-((5-methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)thio)acetamide 13c

IR: 3279 (NH), 3015 (CH aromatic), 2927 (CH aliphatic), 1657 (C = O); 1H NMR: 10.78 (s, 1H), 10.67 (s, 1H), 10.55 (s, 1H), 8.01–7.89 (m, 4H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.71–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (s, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13 C NMR: 166.05, 165.76, 165.07, 164.16, 150.10, 142.41, 141.89, 135.00, 134.55, 133.89, 131.05, 129.08, 127.77, 126.66, 125.62, 119.02, 110.05, 37.32, 21.39; MS (m/z) for C24H19ClN4O4S (494.95): 494.47 (M+, 10%), 402.37 (100%).

4.2. Biological evaluation

4.2.1. In vitro anti-proliferative activity

MTT assay protocol32. This method was applied in accordance with the comprehensive description in Supplementary data.

4.2.2. In vitro VEGFR-2 kinase assay

The assay was applied by ELISA kits in accordance with the comprehensive description in18,33 as described in Supplementary data.

4.2.3. Flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle

This assay was applied using propidium iodide (PI) staining in accordance with the comprehensive description in Supplementary data34,35

4.2.4. Flow cytometry analysis for apoptosis

Apoptotic effect was applied in accordance with the comprehensive description in Supplementary data36,37

4.2.5. Western blot analysis

The western blot technique was applied in accordance with the comprehensive description in Supplementary data38–40

4.3. In silico studies

4.3.1. Docking studies

Docking studies were applied using MOE 201441–43 in accordance with the comprehensive description in were carried out against VEEGFR-2 (PDB ID: 4ASD, resolution: 2.03 Å) as described in Supplementary data.

4.3.2. Pharmacokinetic profiling study

This study was applied using Discover studio 4 in accordance with the comprehensive description in Supplementary data44.

4.3.3. ADME studies

was used to compute the physicochemical properties and predict the drug likeness properties of the most potent compounds This study was applied using the SwissADME online web tool in accordance with the comprehensive description in Supplementary data45–47.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance made by Dr. Mohamed R. Elnagar, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number [PNURSP2022R116], Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:589–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paci A, Veal G, Bardin C, et al. Review of therapeutic drug monitoring of anticancer drugs part 1–cytotoxics. Euro J Cancer 2014;50:2010–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdelgawad MA, El-Adl K, El-Hddad SS, et al. Design, molecular docking, synthesis, anticancer and anti-hyperglycemic assessments of thiazolidine-2, 4-diones Bearing Sulfonylthiourea Moieties as Potent VEGFR-2 Inhibitors and PPARγ Agonists. Pharmaceuticals 2022;15:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Kovar J, Sissons S, et al. A cell-based immunocytochemical assay for monitoring kinase signaling pathways and drug efficacy. Anal Biochem 2005;338:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traxler P, Furet P.. Strategies toward the design of novel and selective protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Pharmacol Therapeutics 1999;82:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang D, Pang X, Lian W, et al. Discovery of VEGFR2 inhibitors by integrating naïve Bayesian classification, molecular docking and drug screening approaches. RSC Adv 2018;8:5286–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Helby A-GA, Sakr H, Ayyad RR, et al. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling, in vivo studies and anticancer activity evaluation of new phthalazine derivatives as potential DNA intercalators and topoisomerase II inhibitors. Bioorg Chem 2020;103:104233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veeravagu A, Hsu AR, Cai W, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors as anti-angiogenic agents in cancer therapy. Recent Patents Anti Cancer Drug Disc 2007;2:59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eissa IH, El-Helby A-GA, Mahdy HA, et al. Discovery of new quinazolin-4 (3H)-ones as VEGFR-2 inhibitors: design, synthesis, and anti-proliferative evaluation. Bioorg Chem 2020;105:104380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ran F, Li W, Qin Y, et al. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle and cancer cell proliferation by new VEGFR inhibitors and their immunomodulator effect: design, synthesis, and biological evaluation. Oxid Med Cellular Longevity 2021;2021:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claesson‐Welsh L, Welsh M.. VEGFA and tumour angiogenesis. J Intern Med 2013;273:114–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Metwally SA, Abou-El-Regal MM, Eissa IH, et al. Discovery of thieno [2, 3-d] pyrimidine-based derivatives as potent VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitors and anti-cancer agents. Bioorg Chem 2021;112:104947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbass EM, Khalil AK, Mohamed MM, et al. Design, efficient synthesis, docking studies, and anticancer evaluation of new quinoxalines as potential intercalative Topo II inhibitors and apoptosis inducers. Bioorg Chem 2020;104:104255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghorab MM, Alsaid MS, Soliman AM, Ragab FA.. VEGFR-2 inhibitors and apoptosis inducers: synthesis and molecular design of new benzo [g] quinazolin bearing benzenesulfonamide moiety. J Enzy Inhib Med Chem 2017;32:893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K, Jeong K-W, Lee Y, et al. Pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening studies for new VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitors. Euro J Med Chem 2010;45:5420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machado VA, Peixoto D, Costa R, et al. Synthesis, antiangiogenesis evaluation and molecular docking studies of 1-aryl-3-[(thieno [3, 2-b] pyridin-7-ylthio) phenyl] ureas: Discovery of a new substitution pattern for type II VEGFR-2 Tyr kinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem 2015;23:6497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garofalo A, Goossens L, Six P, et al. Impact of aryloxy-linked quinazolines: A novel series of selective VEGFR-2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011;21:2106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkady H, Elwan A, El-Mahdy HA, et al. New benzoxazole derivatives as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors and apoptosis inducers: design, synthesis, anti-proliferative evaluation, flowcytometric analysis, and in silico studies. J Enzy Inhib Med Chem 2022;37:397–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papaetis GS, Syrigos KN.. Sunitinib. Bio Drugs 2009;23:377–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soria J-C, DeBraud F, Bahleda R, et al. Phase I/IIa study evaluating the safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of lucitanib in advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 2014;25:2244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahdy HA, Ibrahim MK, Metwaly AM, et al. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling, in vivo studies and anticancer evaluation of quinazolin-4 (3H)-one derivatives as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors and apoptosis inducers. Bioorg Chem 2020;94:103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alanazi MM, Elkady H, Alsaif NA, et al. New quinoxaline-based VEGFR-2 inhibitors: design, synthesis, and antiproliferative evaluation with in silico docking, ADMET, toxicity, and DFT studies. RSC Adv 2021;11:30315–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alanazi MM, Eissa IH, Alsaif NA, et al. Design, synthesis, docking, ADMET studies, and anticancer evaluation of new 3-methylquinoxaline derivatives as VEGFR-2 inhibitors and apoptosis inducers. J Enzy Inhib Med Chem 2021;36:1760–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alanazi MM, Elkady H, Alsaif NA, et al. Discovery of new quinoxaline-based derivatives as anticancer agents and potent VEGFR-2 inhibitors: Design, synthesis, and in silico study. J Mol Struc 2022;1253:132220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Zahabi MA, Sakr H, El-Adl K, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new challenging thalidomide analogs as potential anticancer immunomodulatory agents. Bioorg Chem 2020;104:104218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eldehna WM, Abo-Ashour MF, Ibrahim HS, et al. Novel [(3-indolylmethylene) hydrazono] indolin-2-ones as apoptotic anti-proliferative agents: design, synthesis and in vitro biological evaluation. J Enzy Inhib Med Chem 2018;33:686–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Rashood ST, Hamed AR, Hassan GS, et al. Antitumor properties of certain spirooxindoles towards hepatocellular carcinoma endowed with antioxidant activity. J Enzy Inhib Med Chem 2020;35:831–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Helby A-GA, Ayyad RR, El-Adl K, Elkady H.. Phthalazine-1, 4-dione derivatives as non-competitive AMPA receptor antagonists: design, synthesis, anticonvulsant evaluation, ADMET profile and molecular docking. Mol Div 2019;23:283–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El‐Helby AGA, Ayyad RR, Zayed MF, et al. Design, synthesis, in silico ADMET profile and GABA‐A docking of novel phthalazines as potent anticonvulsants. Archiv Der Pharmazie 2019;352:1800387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ.. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Del Rev 1997;23:3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng H-Y, et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J Med Chem 2002;45:2615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsaif NA, Taghour MS, Alanazi MM, et al. Discovery of new VEGFR-2 inhibitors based on bis ([1, 2, 4] triazolo)[4, 3-a: 3', 4'-c] quinoxaline derivatives as anticancer agents and apoptosis inducers. J Enzy Inhib Med Chem 2021;36:1093–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alsaif NA, Dahab MA, Alanazi MM, et al. New quinoxaline derivatives as VEGFR-2 inhibitors with anticancer and apoptotic activity: design, molecular modeling, and synthesis. Bioorg Chem 2021;110:104807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Lenardo MJ.. Roles of caspases in apoptosis, development, and cytokine maturation revealed by homozygous gene deficiencies. J Cell Sci 2000;113:753–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eldehna WM, Hassan GS, Al-Rashood ST, et al. m. chemistry, Synthesis and in vitro anticancer activity of certain novel 1-(2-methyl-6-arylpyridin-3-yl)-3-phenylureas as apoptosis-inducing agents. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2019;34:322–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo KK-W, Lee TK-M, Lau JS-Y, et al. Luminescent biological probes derived from ruthenium (II) estradiol polypyridine complexes. Inorg Chem 2008;47:200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabt A, Abdelhafez OM, El-Haggar RS, et al. Novel coumarin-6-sulfonamides as apoptotic anti-proliferative agents: synthesis, in vitro biological evaluation, and QSAR studies. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2018;33:1095–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balah A, Ezzat O, Akool E-S.. Vitamin E inhibits cyclosporin A-induced CTGF and TIMP-1 expression by repressing ROS-mediated activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in rat liver. Inter Immunopharmacol 2018;65:493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aborehab NM, Elnagar MR, Waly NE.. Gallic acid potentiates the apoptotic effect of paclitaxel and carboplatin via overexpression of Bax and P53 on the MCF‐7 human breast cancer cell line. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2021; 35:e22638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elnagar MR, Walls AB, Helal GK, et al. Functional characterization of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine and NMDA receptor signaling in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in an ERK phosphorylation assay. Euro J Pharmacol 2018;826:106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belal A, Elanany MA, Santali EY, et al. Screening a panel of topical ophthalmic medications against MMP-2 and MMP-9 to investigate their potential in keratoconus management. Molecules 2022;27:3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elkaeed EB, Youssef FS, Eissa IH, et al. Multi-step in silico discovery of natural drugs against COVID-19 targeting main protease. Inter J Mol Sci 2022;23:6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkaeed EB, Elkady H, Belal A, et al. Multi-phase in silico discovery of potential SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors among 3009 clinical and FDA-approved related drugs. Processes 2022;10:530. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdallah AE, Alesawy MS, Eissa SI, et al. Design and synthesis of new 4-(2-nitrophenoxy) benzamide derivatives as potential antiviral agents: Molecular modeling and in vitro antiviral screening. N J Chem 2021;45:16557–71. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V.. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep 2017;7:42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V.. iLOGP: a simple, robust, and efficient description of n-octanol/water partition coefficient for drug design using the GB/SA approach. J Chem Inform Model 2014;54:3284–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ.. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012;64:4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.