Abstract

The epitrochlear lymph nodes (ELN) are rarely examined clinically and are difficult to identify radiologically in healthy patients. They are, therefore, generally under appreciated as a source of significant pathology. Despite this, enlargement of an ELN is almost always secondary to a pathological process, the differential for which is relatively narrow. The following pictorial review illustrates the spectrum of infectious, inflammatory and malignant conditions affecting the ELN, some of which are quite specific to this location. We also emphasise the importance of distinguishing enlarged ELNs from benign and malignant non-nodal soft tissue masses, which can have very similar clinical presentation and imaging appearances.

Introduction

The epitrochlear lymph nodes (ELN) are the main peripheral nodal station of the upper limb, receiving lymphatic drainage from the ulnar-side-of the hand and forearm. They lie consistently 1–2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle, just posterior to the basilic vein and medial to the brachialis muscle (Figure 1). They are rarely palpable in the absence of disease and infrequently examined by clinicians. As a result, they are often overlooked as a source of significant pathology.

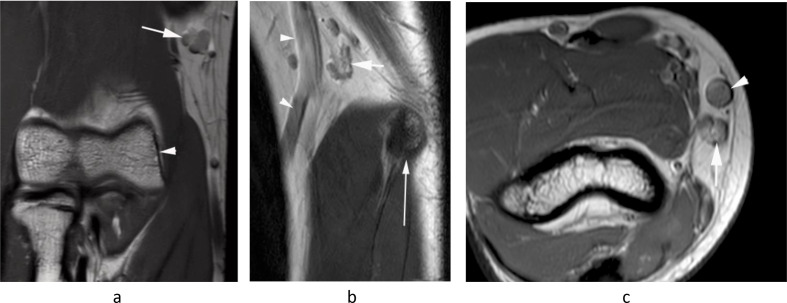

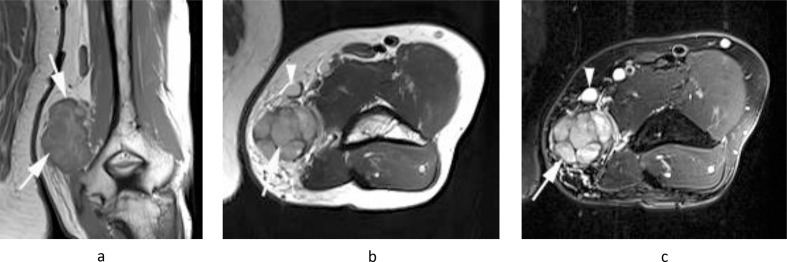

Figure 1.

A 16-year-old boy being imaged for right elbow pain. (a) Coronal PDW FSE MR image shows the normal epitrochlear lymph node (arrow) located ~2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle (arrowhead). (b) Sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial PDW FSE MR images show the epitrochlear lymph node (arrows) located directly posterior to the basilic vein (arrowheads) and ~2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle (thin arrow-b).

The aim of this pictorial review is to outline the differential diagnosis for a pathological ELN, ranging from infective/inflammatory conditions such as cat scratch disease, through to lymphoma and miscellaneous tumours of the upper limb with a tendency for loco-regional lymph node spread. Mimics of ELN masses, including neurogenic tumours and primary soft tissue sarcomas, are also discussed.

Non-neoplastic nodal lesions

Infectious lymphadenitis

Infectious lymphadenitis is one of the more well-recognised causes of isolated ELN enlargement. Cat-scratch disease is a bacterial infection caused by bartonella henselae, a gram-negative bacillus usually introduced by the scratch or bite of a cat. The hallmark of this disease is painful lymphadenopathy proximal to the site of inoculation. ELNs are a common site, being a lymphatic drainage pathway (first order nodes) from the hand. The infection usually resolves in 1–4 months, but may produce chronic lymphadenitis for up to a year.1

Imaging findings are variable but often defined by a significant inflammatory component. On ultrasound (US), there is usually a mildly hypoechoic hypervascular soft tissue mass with surrounding hyperechoic fat and possibly a fluid collection (Figure 2a). On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion demonstrates isointense T1W signal intensity and heterogeneously hyperintense signal intensity on fat-saturated images. Half of these lesions have satellite nodes, and the majority will show peri-lesional oedema/stranding or enhancement. Occasionally, thick-walled enhancing fluid collections may be present. (Figure 2b, c).1

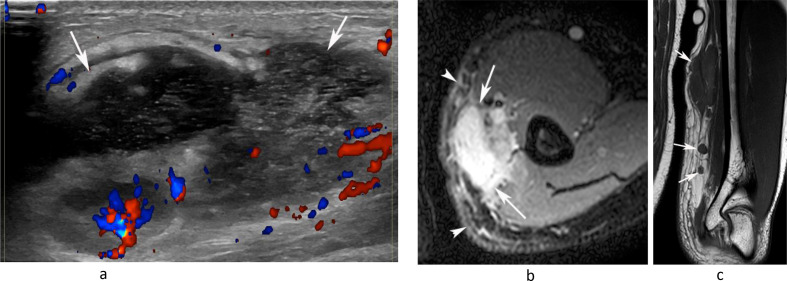

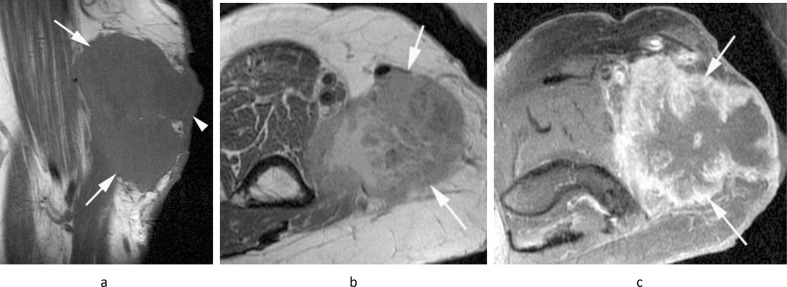

Figure 2.

A 20-year-old male presenting with a painful swelling of the medial distal arm. (a) Longitudinal Doppler US demonstrates a poorly defined mixed echogenicity hypervascular mass with internal fluid collection (arrows). (b) Axial PD-SPAIR and (c) coronal T1W TSE MR images show a large heterogeneously T1 isointense/SPAIR hypeintense mass with a fluid collection and multiple smaller enlarged medial epitrochlear lymph nodes (arrows-c) with inflammatory oedema-like signal and stranding in the surrounding soft tissues (arrowheads-b). Histology confirmed necrotising granulomatous lymphadenitis.

There have been rarely described cases of epitrochlear tuberculous lymphadenitis.2 Imaging findings are somewhat non-specific, but the presence of significant necrosis within the lymph node may suggest the diagnosis. Tuberculous lymphadenitis has also been known to fistulate and extend into subcutaneous tissue, forming a so-called “collar stud” abscess (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A 49-year-old female presenting with an ulcerating mass on the inner margin of the right arm just above the elbow. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) axial PD-SPAIR MR images and (c) longitudinal US show a lobular hypoechoic mass (arrows), isointense on T1 and heterogeneously hyperintense on SPAIR images, which is forming a sinus to the skin (arrowheads-a,b), the features being consistent with a “collar stud” abscess. Biopsy revealed chronic necrotising granulomatous infection consistent with tuberculosis.

Various other infectious diseases have been implicated in the emergence of enlarged ELNs including the parasitic roundworm infection, filariasis, leprosy and cutaneous leishmaniasis. These could be considered if the patient is an emigrant or returning traveller from an endemic country.3

Inflammatory lesions

Kimura disease, also known as eosinophilic hyperplastic lymphogranuloma, is another chronic inflammatory disorder, which can localise to the ELNs, usually presenting as painless lymphadenopathy in young Asian patients.4 MRI will demonstrate a poorly defined subcutaneous mass in the epitrochlear region, isointense on T1W and hyperintense on T2W, usually demonstrating diffuse homogeneous enhancement post-gadolinium.4

Neoplastic nodal lesions

Lymphoma

Lymphoma is the commonest cause of a malignant epitrochlear mass.3 In a report by Selby et al3, which included patients with only stage III and stage IV diseases, 33% of patients with non-Hodgkin”s lymphoma and 20% of patients with Hodgkin”s lymphoma had palpable epitrochlear lymphadenopathy. The clinical significance of epitrochlear nodal involvement in lymphoma is uncertain, as it is generally referred to in the literature as occurring in widespread high-grade or relapsed disease.5 However, isolated disease can present initially as a non-specific nodal mass in the medial epitrochlear region (Figure 4).6

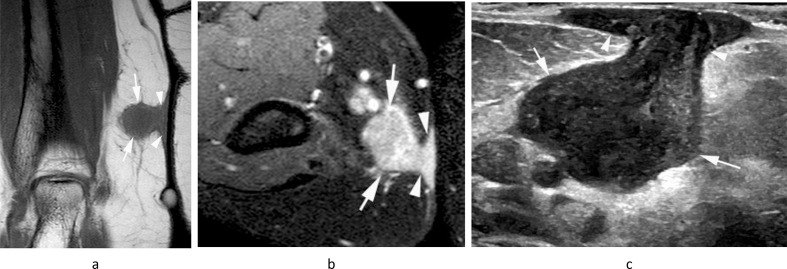

Figure 4.

A 66-year-old female presenting with a large mass in the medial epitrochlear space. (a) Coronal T1W TSE and (b) axial PD-SPAIR MR images show a somewhat poorly defined mass (arrows) displacing the basilic vein which is homogeneously isointense on T1 and hyperintense on SPAIR. (c) Longitudinal Doppler US shows a homogeneous hypoechoic hypervascular mass. Histology confirmed a diagnosis of lymphoma.

Skin cancer metastases

Primary melanoma in the distal upper extremity is most commonly seen in the forearm, followed by the dorsum of the hand and the nail-tip complex of the digit. Metastasis to regional nodes is seen in 50% of cases and despite predominantly metastasising to the axillary basin, melanoma can spread “in transit” to the epitrochlear nodes with reported rates of up to 20% (Figure 5).7

Figure 5.

A 61-year-old male with a previous history of melanoma presenting with a mass in the medial epitrochlear space. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) axial T2W FSE and (c) axial PD-SPAIR MR images show a lobular and heterogenous mildly T1 and T2 hyperintense mass (arrows) contacting the basilic vein (arrowheads-b,c). Histology confirmed melanoma metastasis.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and Merkel cell carcinoma of the distal upper extremity are other malignant cutaneous tumours, which may metastasise to epitrochlear lymph nodes, albeit with less frequency than melanoma.8

Other metastases

Loco-regional lymph node metastases from sarcomas are rare, but it is still possible for the epitrochlear basin to act as an “in-transit” site of lymphatic spread for a small percentage of these tumours when located in the upper limb (Figures 6–8). Coincidentally, three of the commonest soft tissue sarcomas of the distal upper extremity: epithelioid, clear cell (Figure 6) and synovial sarcoma (Figure 7) have the highest rates of nodal metastases among all soft tissue sarcomas, with some sarcoma centre protocols mandating cross-sectional imaging of the whole arm to exclude spread to epitrochlear and axillary nodes in such cases.9

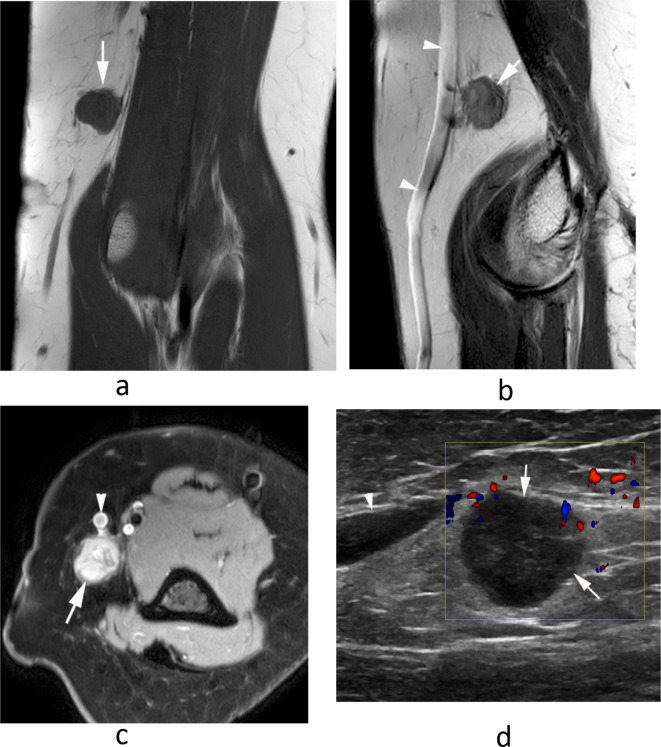

Figure 6.

A 39-year-old female with a history of clear cell sarcoma of the hand treated 3 years previously, now presenting with a small mass in the medial epitrochlear space. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial PD-SPAIR MR images show a small lobular mass (arrows) located directly posterior to the basilic vein (arrowheads-b,c), isointense on T1 and T2 and heterogeneously hyperintense on SPAIR, consistent with a nodal mass. (d) Longitudinal US shows a homogeneous hypoechoic mass (arrows) located adjacent to the basilic vein (arrowhead). Histologically confirmed clear cell sarcoma metastasis.

Figure 7.

A 77-year-old male with a painful swollen right elbow. (a) Sagittal T2W gradient echo and (b) axial PDW FSE MR images show a homogeneously T2 hyperintense soft tissue mass in the posterior recess of the elbow (arrows) with erosion of the olecranon (arrowheads-a) and enlargement of the epitrochlear lymph node (double arrowhead-b). The patient had a known intra-articular synovial sarcoma of the elbow joint.

Figure 8.

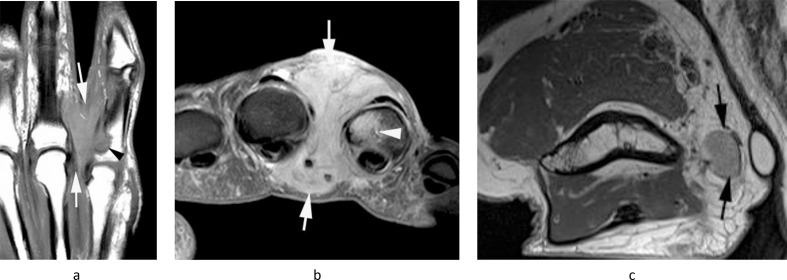

A 74-year-old male presenting with a painful swelling on the ulnar-side of the right hand and a small mass in the medial epitrochlear space. (a) Coronal T1W TSE and (b) axial PD-SPAIR MR images show a poorly defined T1 isointense, SPAIR hyperintense soft tissue mass in the fourth webspace (arrows) which is eroding the little finger proximal phalanx (arrowhead-b). (c) Axial PDW FSE MR image through the distal arm shows a small oval mildly hyperintense mass (arrows) in the location of the epitrochlear lymph node. Histologically confirmed undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma at both sites.

ELN metastases may also very rarely occur from malignant tumours arising in distant sites such as the lung (Figure 9) and prostate (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

An 86-year-old female with a previous history of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung who developed a large fungating mass in the medial epitrochlear space. (a) Sagittal T1W TSE, (b) axial T2W FSE and (c) axial fat suppressed post-gadolinium T1W TSE MR images show a poorly defined mass with a solid enhancing outer component and fluid signal intensity necrotic centre (arrows). Histologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma metastasis.

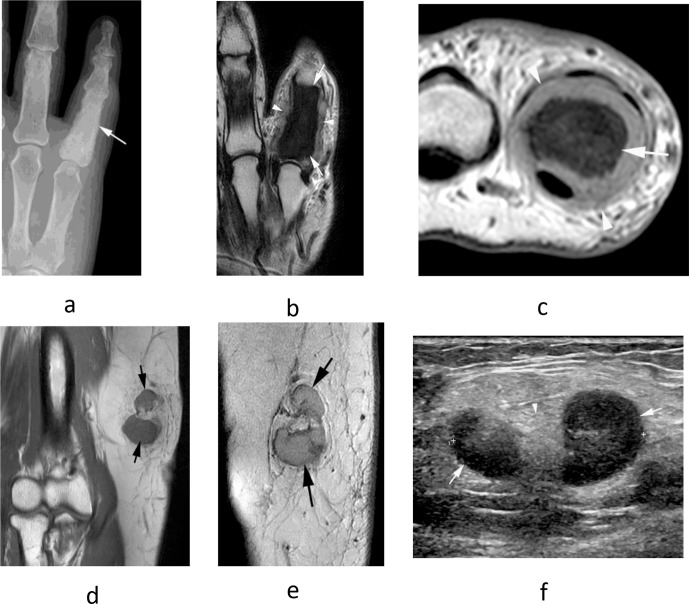

Figure 10.

A 69-year-old male presenting with painful swelling of the little finger. (a) Dorso-palmar radiograph shows diffuse sclerosis of the little finger proximal phalanx (arrow). (b) Coronal T2W FSE and (c) axial PDW FSE MR images show diffuse reduction of marrow signal in the little finger proximal phalanx (arrows) with circumferential soft tissue extension (arrowheads). (d) Coronal T1W TSE and (e) sagittal T2W FSE MR images as well as (f) longitudinal US show lobular enlargement of the epitrochlear lymph node (arrows), isointense on T1 and slightly hyperintense on T2, with a maintained fatty hilum on US (arrowhead-f). Histologically confirmed metastatic prostate carcinoma at both sites.

Imaging features of malignant epitrochlear nodes

The imaging features of malignant ELNs are relatively non-specific, usually presenting as enlarged (>1 cm maximum cross-section), rounded hypoechoic lesions on US with loss of their central fatty hilum (Figure 6d), and peripheral hypervascularity rather than the central vascularity seen in normal or reactive lymph nodes. MRI features are variable, but usually the nodes are fairly homogeneous in signal intensity, being slightly hyperintense on T2W and iso/hypointense on T1W (Figures 7, 8 and 10). Certain features such as extensive necrosis could suggest squamous cell metastasis (Figure 9), while intranodal T1W hyperintensity could suggest melanoma metastasis due to intralesional haemorrhage or melanin (Figure 5).10

Epitrochlear lymph node mimics

Peripheral nerve sheath tumours

The commonest extra nodal lesions arising in the medial epitrochlear region are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumours (PNST), usually of the median or ulnar nerves as they course past the medial epicondyle. The differential diagnosis lies between a schwannoma or neurofibroma, but it is difficult to make this distinction on imaging alone.11

US of both schwannomas and neurofibromas reveals a well-defined homogeneously hypoechoic fusiform mass oriented longitudinally along the nerve, and there may be posterior acoustic enhancement simulating a cyst (Figure 11a). On MRI, PNSTs are typically located in the anatomic location of a known nerve and are classically low-to-intermediate SI on T1W and hyperintense on T2W (Figures 11b, c, 12a and b). There may be a “target sign” with peripheral high T2W signal intensity and central low T2W signal intensity representing central fibrous tissue surrounded by myxoid tissue (Figure 12b). A “split fat” sign, whereby a rind of preserved fat is seen around the lesion is somewhat less specific for PNST but suggests that the tumour lies within the intermuscular space, a common site for PNSTs.11 The “fascicular” sign characterised by multiple ring-like hypointense foci within the T2W hyperintense lesion, and entering/exiting nerve signs whereby a nerve is clearly seen entering and exiting the fusiform mass, are also typical findings (Figures 11b and 12a).

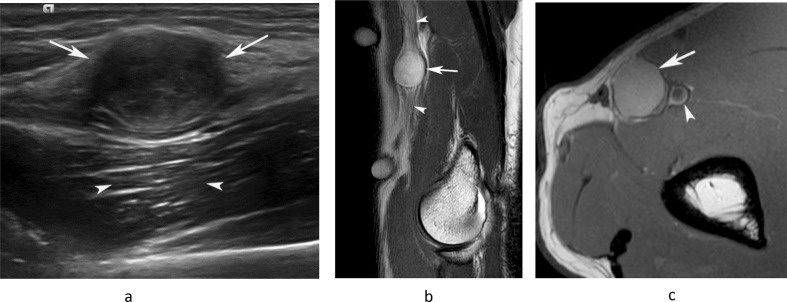

Figure 11.

A 46-year-old male presenting with a small mass in the medial distal arm. (a) Longitudinal US study demonstrates a homogeneous hypoechoic mass (arrows) with posterior acoustic enhancement (arrowheads). (b) Sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial PDW FSE MR images show a well-defined, homogeneously hyperintense oval mass (arrows) arising in relation to the median nerve (arrowheads-b) and brachial artery (arrowhead-c). (c). Histologically confirmed schwannoma.

Figure 12.

A 62-year-old female presenting with a swelling in the medial distal arm. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial fat-suppressed PDW FSE MR images show a lobular homogeneous T1 isointense and heterogeneous T2 hyperintense oval mass (arrows) arising in relation to the ulnar nerve (arrowheads-a). The lesion demonstrates a “target” sign’, with low central T2 signal (arrowhead-b) and is separated from the basilic vein (arrowhead-c) consistent with its extra nodal origin. Histologically confirmed schwannoma.

Any lesion, which is painful and/or associated with functional loss, is particularly large or growing rapidly, demonstrates peripheral enhancement, peri-lesional oedema and/or has an intratumoral cystic component should prompt consideration of transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST) (Figure 13).

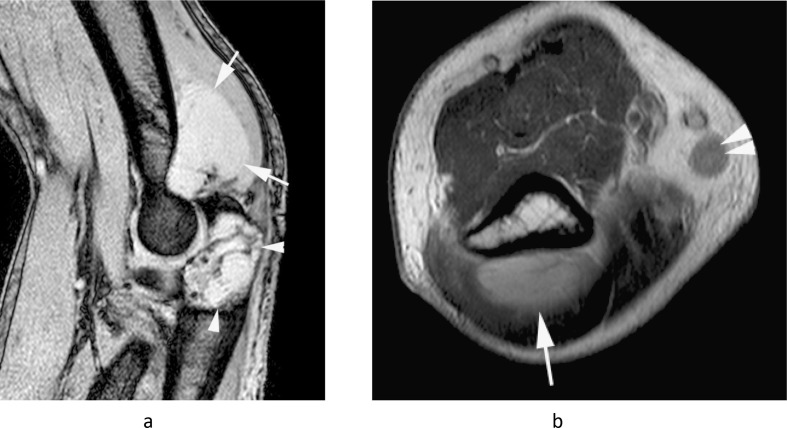

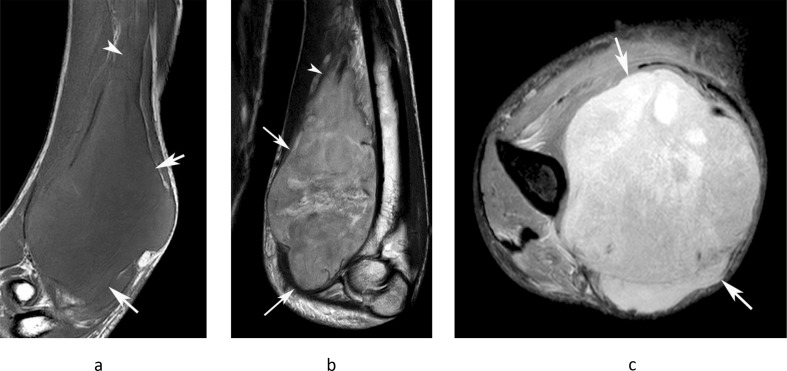

Figure 13.

A 35-year-old male presenting with a large painful swelling in the medial distal arm which had rapidly grown over the previous month, along with new paresthesia in the hand. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial PD-SPAIR MR images show a poorly defined heterogeneous T1 isointense and T2/SPAIR iso-hyperintense mass (arrows) extending proximally along the median nerve (arrowheads-a,b). Histologically confirmed high-grade MPNST.

Primary soft tissue sarcoma

Practically speaking, any soft tissue sarcoma can present in the medial epitrochlear region, but there are certain subtypes such as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS, previously termed malignant fibrous histiocytoma) and synovial sarcoma which are relatively more common in the upper extremity.12 As with all soft tissue sarcomas, MRI findings are relatively non-specific but more aggressive features such as poor margins, heterogeneous signal intensity and an infiltrative growth pattern along fascial planes would favour high-grade undifferentiated tumours such as UPS (Figure 14),13 while a deep location, smooth margins and juxta-articular location may favour synovial sarcoma.14 Ensuring that the lesion is not in the typical location of the ELNs, immediately posterior to the basilic vein, 1–2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle, should avoid mistaking these lesions for pathological lymph nodes.

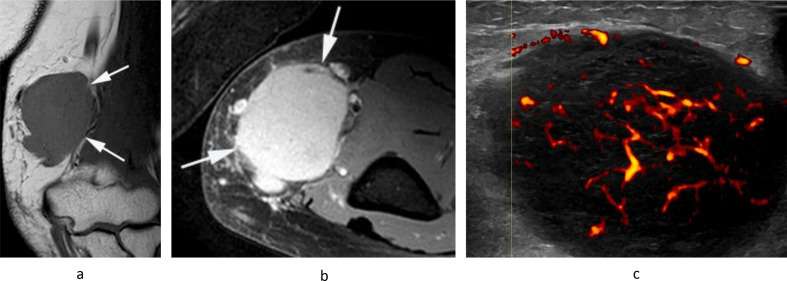

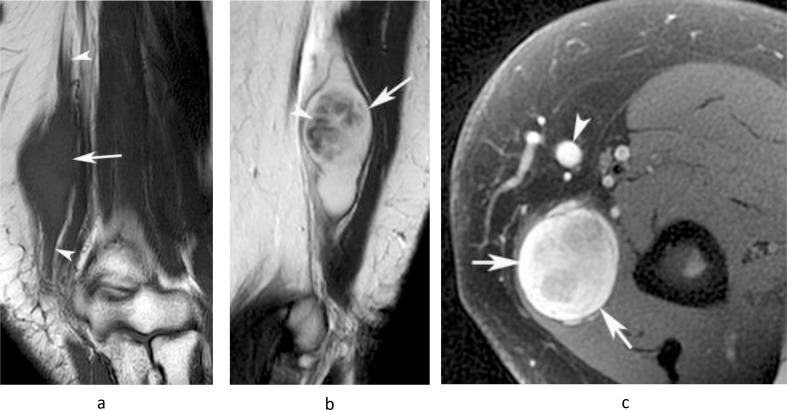

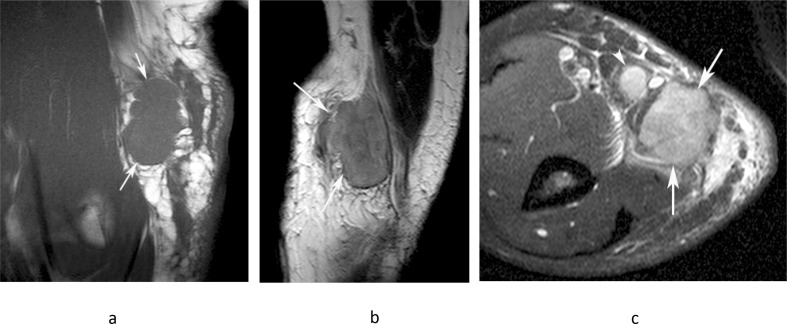

Figure 14.

A 63-year-old male presenting with a painful mass in the medial distal arm. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial PD-SPAIR MR images show a poorly defined heterogeneous intermediate T1 and T2 signal intensity mass (arrows) with prominent reactive peri-lesional oedema and a metastasis to the adjacent epitrochlear lymph node (arrowhead-c). Histologically confirmed undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) arising from smooth muscle cells of the vessel wall deserves special mention, as while rare, they have the potential to arise directly from or adjacent to the basilic vein thus simulating a nodal mass. Smaller more superficial lesions tend to be well-defined and homogeneously high signal intensity on T2W, while larger lesions can exhibit significant necrosis and haemorrhage (Figure 15).15

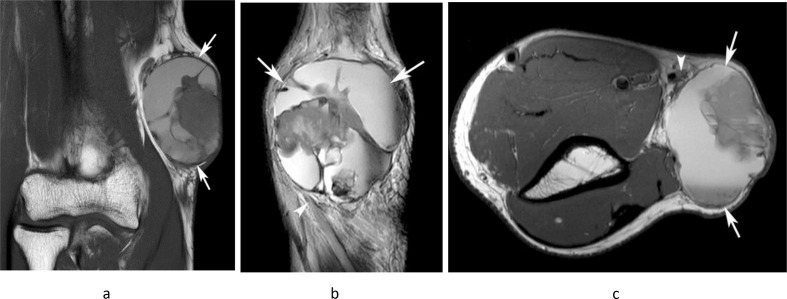

Figure 15.

A 48-year-old male presenting with a large mass in the medial distal arm. (a) Coronal T1W TSE, (b) sagittal T2W FSE and (c) axial PDW FSE MR images show a well-defined lobular mass (arrows) located posterior to the basilic vein (arrowhead-c), which demonstrates extensive haemorrhagic necrosis, as demonstrated by regions of T1 hyperintensity with a fluid–fluid level and a peripheral T1/T2 isointense solid component. Histologically confirmed high-grade leiomyosarcoma.

Management of epitrochlear masses

Any patient with an epitrochlear soft tissue mass should undergo a full clinical history and examination. Young patients presenting with painful lymphadenopathy, particularly in the presence of systemic symptoms such as fever and fatigue should prompt suspicion for infectious lymphadenitis, while generalised lymphadenopathy, night sweats and weight loss could suggest an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder. Lesions, which are growing rapidly and/or >5 cm in size at presentation, should be considered malignant until proven otherwise, prompting urgent ultrasound investigation. On US, a soft tissue lesion of any size or a node measuring >1 cm in cross-section with loss of its normal central fatty architecture should prompt further investigation with MRI.16

As it is often not possible to conclusively distinguish between a benign and malignant epitrochlear mass on imaging alone, all of these lesions will require expert radiological review and possible biopsy, preferably at a tertiary centre specialised in the management of soft tissue tumours. The only lesions which may preclude biopsy and proceed directly to surgical excision are PNSTs which exhibit typical features as previously described, or lesions < 2 cm in maximum dimension for which needle biopsy may not yield sufficient tissue.

US-guided percutaneous core biopsy under local anaesthesia, obtaining several cores to increase diagnostic yield, is the preferred method to obtain tissue, and consensus should be obtained from an orthopaedic oncological surgeon to decide on the most appropriate approach to avoid contamination outside of the surgical plane. There is no role for fine needle aspiration in the context of an indeterminate soft tissue mass. In addition to sending samples for histopathological analysis, tissue should also be sent to microbiology to isolate causative organisms in infectious lymphadenitis.1

If the pathology returns as a malignant sarcoma, further staging investigations will be required, usually in the form of a CT chest. However, CT staging of the abdomen and pelvis is also advocated in cases of myxoid liposarcoma which has a tendency for extra skeletal metastases, particularly the retroperitoneum and peritoneal cavity.17 As previously mentioned, synovial sarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma and clear cell sarcoma will require an MRI or CT of the whole arm, including the axilla, to evaluate for regional lymph node spread.16

Conclusions

The epitrochlear nodes are frequently overlooked as a source of significant pathology as they are rarely palpable and difficult to identify radiologically in healthy patients. Despite this, their enlargement is almost always secondary to a pathological process, the differential for which is relatively narrow. The current review aims to educate the reader on the spectrum of infectious, inflammatory and malignant conditions which may localise to the epitrochlear nodes. We also emphasise the importance of distinguishing pathologically enlarged nodes from benign and malignant soft tissue masses, which can have very similar imaging appearances.

Contributor Information

William Tilden, Email: wtilden5@gmail.com.

Asif Saifuddin, Email: asif.saifuddin@nhs.net.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernard SA, Walker EA, Carroll JF, Klassen-Fischer M, Murphey MD. Epitrochlear cat scratch disease: unique imaging features allowing differentiation from other soft tissue masses of the medial arm. Skeletal Radiol 2016; 45: 1227–34. doi: 10.1007/s00256-016-2407-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crum NF. Tuberculosis presenting as epitrochlear lymphadenitis. Scand J Infect Dis 2003; 35(11-12): 888–90. doi: 10.1080/00365540310016899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selby CD, Marcus HS, Toghill PJ. Enlarged epitrochlear lymph nodes: an old physical sign revisited. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1992; 26: 159–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi J-A, Lee G-K, Kong KY, Hong SH, Suh JS, Ahn JM, et al. Imaging findings of kimura’s disease in the soft tissue of the upper extremity. Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184: 193–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang BK, Backstrand KH, Ng AK, Silver B, Hitchcock SL, Mauch PM. Significance of epitrochlear lymph node involvement in Hodgkin disease. Cancer 2001; 91: 1213–8. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yardimci VH, Yardimci AH. An unusual first manifestation of Hodgkin lymphoma: Epitrochlear lymph node İnvolvement—A case report and brief review of literature. J of Med High Impact Case Rep 2017; 5: 232470961770670. doi: 10.1177/2324709617706709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner JB, Rinker B. Melanoma of the hand: current practice and new frontiers. Healthcare 2014; 2: 125–38. doi: 10.3390/healthcare2010125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph MG, Zulueta WP, Kennedy PJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the trunk and limbs: the incidence of metastases and their outcome. Aust N Z J Surg 1992; 62: 697–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal J, Cardona K, Sayyid SK, Perricone AJ, Reimer N, Monson D, et al. Nodal metastases of soft tissue sarcomas: risk factors, imaging findings, and implications. Skeletal Radiol 2020; 49: 221–9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-019-03299-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luciani A, Itti E, Rahmouni A, Meignan M, Clement O. Lymph node imaging: basic principles. Eur J Radiol 2006; 58: 338–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chee DWY, Peh WCG, Shek TWH. Pictorial essay: imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Can Assoc Radiol J 2011; 62: 176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kransdorf MJ. Malignant soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995; 164: 129–34. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.1.7998525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo HJ, Hong SH, Kang Y, Choi J-Y, Moon KC, Kim H-S, et al. MR imaging of myxofibrosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma with emphasis on tail sign; diagnostic and prognostic value. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 1749–57. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3181-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakri A, Shinagare AB, Krajewski KM, Howard SA, Jagannathan JP, Hornick JL, et al. Synovial sarcoma: imaging features of common and uncommon primary sites, metastatic patterns, and treatment response. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199: W208–15. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abed R, Abudu A, Grimer RJ, Tillman RM, Carter SR, Jeys L. Leiomyosarcomas of vascular origin in the extremity. Sarcoma 2009; 2009: 1–4. doi: 10.1155/2009/385164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dangoor A, Seddon B, Gerrand C, Grimer R, Whelan J, Judson I. Uk guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res 2016; 6: 20. doi: 10.1186/s13569-016-0060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estourgie SH, Nielsen GP, Ott MJ. Metastatic patterns of extremity myxoid liposarcoma and their outcome. J Surg Oncol 2002; 80: 89–93. doi: 10.1002/jso.10093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]