Summary

Value co‐creation focuses on creating value with and for multiple stakeholders — through purposeful engagement, facilitated processes and enriched experiences — to co‐design new products and services. User‐centred design enables multidisciplinary teams to design and develop or adapt resources from the end user’s perspective.

Combining value co‐creation and user‐centred design offers an effective, efficient, user‐friendly and satisfying experience for all participants, and can result in co‐created, tailored and fit‐for‐purpose resources. These resources are more likely to be adopted, be usable, be sustainable and produce outcomes that matter, and thereby create value for all parties.

Over the past 6 years, the Education and Innovation Department at Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited has used these methods to co‐create education and training programs to build workforce capacity and support implementation of many person‐centred integrated care programs.

In this article, we present examples of how Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited used value co‐creation and user‐centred design to develop and deliver education programs in primary health care, and offer insights into how program developers can use these methods to co‐create any health care product, service or resource to better address end user needs and preferences.

As we strive to strengthen the role of consumers as active partners in care and improve service delivery, patient outcomes and patient experiences in Australia, it is timely to explore how we can use value co‐creation and user‐centred design at all levels of the system to jointly create better value for all stakeholders.

Keywords: Health systems; Primary health care; Inflammatory bowel diseases; General practice; Primary care; Referral and consultation; General practice; Delivery of healthcare; Health communication; Quality of health care; Education, professional

Over the past 20 years, value co‐creation (often referred to as co‐creation) has been increasingly used across diverse sectors and applied in many ways. 1 Typically used in the business sector, value co‐creation supports multimillion dollar businesses to better understand end user expectations, spark meaningful dialogue and improve value for all. 2 It has taken several years for value co‐creation to gain momentum in other sectors, but now the health 3 , 4 , 5 and research 6 , 7 , 8 sectors use it to co‐create outcomes of value for end users, and the public sector applies it to boost innovation. 9 Value co‐creation practices within education are developing and include generative dialogue, negotiation, and collaborative and reciprocal processes whereby all stakeholders contribute variously to curricular or pedagogical conceptualisation, decision making and implementation. 10 , 11 , 12

Value co‐creation focuses on creating value with and for multiple stakeholders and end users through facilitated processes and interactive platforms. 1 , 2 , 11 , 12 It redefines the way an organisation engages people internally and externally, and uses a process of proactive and purposeful engagement focused on enriched experiences to collectively co‐design new products and services and garner strategic insight to add value. 13

Co‐design, informed by the principles of user‐centred design, 14 is another effective approach that many sectors use to support multidisciplinary teams in co‐designing or adapting products, services or resources from the perspective of how the end user will understand and use them. 15 , 16

Evidence suggests that value co‐creation and user‐centred design approaches can be flexible, systematic, holistic and iterative means of developing tailored, fit‐for‐purpose education resources. 17 , 18 , 19 Engaging with end users and other stakeholders to directly tailor resource content and delivery mode to meet their needs and preferences makes it more likely that the resources will be adopted, be used long term, be sustainable, and help to co‐create outcomes of value. 14 , 20 , 21 , 22

For the past 6 years, the Education and Innovation Department of Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited (AGPAL) has used value co‐creation and user‐centred design to co‐create education resources and training programs to enhance workforce capacity and strengthen the implementation of many national and state‐based person‐centred and integrated care programs. 6

Here, we present two case studies to show other trainers and health care program developers how they can engage with end users and key stakeholders to co‐create their own education resources or potentially any other solution in primary health care.

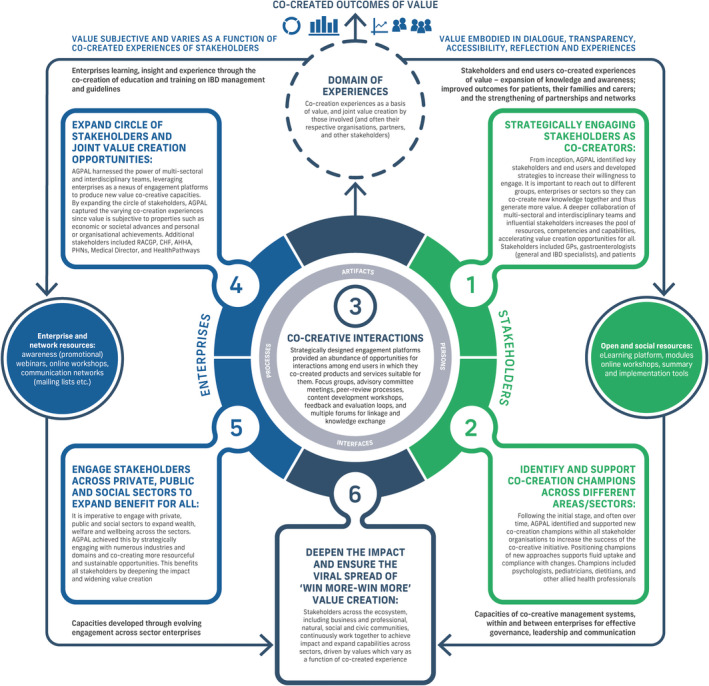

Value co‐creation for developing and delivering education resources and training programs follows six steps

Value co‐creation follows six steps. The processes that AGPAL implemented in each step to co‐create education resources and training programs are shown in Box 1. AGPAL applied the six steps of value co‐creation with targeted populations of stakeholders and end users, using an advisory committee, action‐focused working groups and a forum. Subject matter experts were encouraged to collaborate and work with key stakeholders: care providers in integrated care (doctors, nurses, specialists, allied health professionals, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers and practitioners, and social workers); patients, their families and their carers; and other stakeholders in the private, public and social sectors.

Box 1. How Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited co‐created education resources and training programs within the six steps of value co‐creation*.

IBD = inflammatory bowel disease. AGPAL = Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited. RACGP = Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. CHF = Consumer Health Forum of Australia. AHHA = Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association. PHN = Primary Health Network. GP = general practitioner. * Adapted from Ramaswamy and Ozcan (2014) 2 and Janamian and colleagues (2016). 6 ◆

Case study 1: Inflammatory Bowel Disease GP Aware Project

The Inflammatory Bowel Disease National Action Plan 2019 emphasised the need to improve awareness, management and referral of people living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). 23 In response, Crohn’s and Colitis Australia, working with the Gastroenterological Society of Australia and AGPAL, secured funding from the Australian Government Department of Health for education and awareness‐raising activities that align with recommended actions in the plan — specifically, Priority Area 3, which is to support general practitioners to more effectively participate in IBD management. 23 , 24

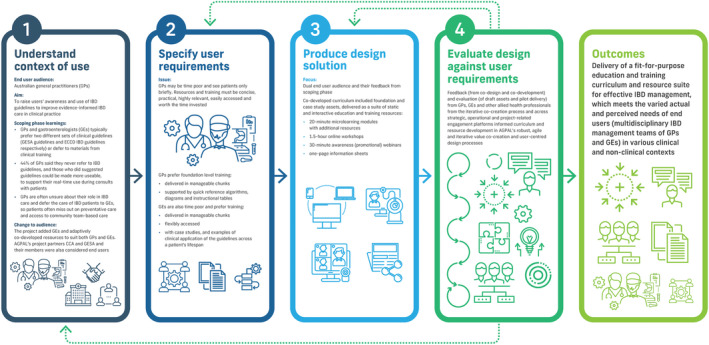

We purposefully partnered with stakeholders and end users to map knowledge gaps, identify learner needs, ideate, problem solve, transform and mature knowledge, provide context to inform the development of content, and review and revise content. This resulted in an education and training curriculum, resources, and delivery modes that were co‐created with stakeholders and end users, and tailored to end users. The objective was to use awareness raising, education and continuing professional development to improve general practitioner capacity to support IBD patients. AGPAL’s application of the six steps of value co‐creation to co‐design and develop the education and training resources for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease GP Aware Project is described online, along with details on the user‐centred design approach that was used to develop the training (adapted from the International Organization for Standardization’s standard ISO 9241‐210:2019; Box 2), 25 and a description of the various engagement platforms that were developed to co‐create this project (Supporting Information, table 1 and table 2).

Box 2. The user‐centred design approach*.

* Adapted from ISO 9241‐210:2019. 25 ◆

Today, the value of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease GP Aware Project extends beyond delivering new knowledge and strategic assets. It is helping to develop capability ecosystems at the frontline of IBD care in Australia, and its educational resources and ongoing engagement platforms are focusing on six evidence‐based topics:

-

▪

the GP’s role in early detection of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis;

-

▪

early intervention, therapies, referral and triage;

-

▪

management of IBD and preventive health;

-

▪

multidisciplinary team‐based care;

-

▪

managing patients with complex conditions — ages and stages; and

-

▪

managing complex IBD issues – relapse and comorbidity.

This curriculum is delivered through flexible and fit‐for‐purpose channels. The first of these is a set of six interactive e‐learning modules hosted on a digital platform that was co‐designed to optimise the learning experience. The interactive modules, which have continuing professional development endorsement, explore the lifelong journeys of patients “Emma” and “Fred” through a sequential series of animations, infographics, knowledge checks and other supportive assets. The second is a collection of digital workshops and webinars aimed at supporting meaningful engagement with the curriculum. It includes six interactive online workshops (each delivered four times) that are facilitated by subject matter experts and delivered in a manner designed to encourage transformational learning in a supportive peer environment. User analytics, ongoing engagement metrics and stakeholder feedback will inform the next iteration of each asset, ensuring it is fit for purpose and cost effective, and that it meets the actual and perceived audience needs.

Case study 2: Brisbane South Primary Health Network Person‐Centred Care Practice Initiative

The Brisbane South Primary Health Network (PHN) Person‐Centred Care Practice Initiative supports general practices to: build their practice team; embed change concepts from the Patient‐Centred Medical Homes framework, for a more sustainable practice; and improve patient outcomes. AGPAL was engaged to develop and deliver a multiphase training program of e‐learning modules and innovative, practical tools that inform practice transformation 26 in the journey towards higher performing primary health care. 27 This required an education suite that could flexibly meet the needs of the diverse end user audience. PHNs and the primary care teams that they support are excellent examples of the end users of these resources (ie, clinical, non‐clinical, operational and administrative staff), who have a range of skill sets and must work together to co‐create genuine, informed and measured health care transformation.

The 18‐month education program involved co‐design, development and delivery of education and training across two tiers of leadership in the Brisbane South PHN region: (i) PHN practice support and optimal care program teams, for whom a train‐the‐trainer approach to building practice capacity and increasing practice sustainability was used; and (ii) practice leaders, usually practice managers or general practitioners, who would act as agents of change at the general practice level. Developing education resources that are more fit for purpose and relevant to each end user helps to increase adoption, long‐term usability and sustainability of the resources and expand the value for all individuals, organisations and, ultimately, consumers. Details regarding how AGPAL used value co‐creation and user‐centred design to develop this program, and the various engagement platforms that AGPAL developed to strengthen its co‐creation, are provided online (Supporting Information, table 3 and table 4).

Valuable lessons were learned along the way

Five key lessons were learned across our value co‐creation experiences:

-

▪

A clear shared purpose and ongoing meaningful dialogue throughout the value co‐creation journey, and a demonstrated ability to directly respond to stakeholder and end user needs, lead to a more relational rather than transactional approach. This translates into an optimised user experience, more meaningful engagement for all stakeholders, and a transformation that exceeds stakeholder expectations. The more that stakeholders and end users realise that organisations or health services are committed to listening to, embracing and addressing their requirements, the more they want to be involved with that organisation and their programs.

-

▪

The readiness of parties to embrace the commitment, transparency and responsibility of value co‐creation can be variable. It is essential to select the right stakeholders and end users to work with, and deepen their capabilities over time, ensuring that they understand their impact on the developmental process, end user perception and sustainability. When engaging new stakeholders and end users, it is best to start on a small project, and support them to learn and grow. In each case study presented, subject matter experts were engaged proportionally to their co‐creation experience, with each project acting as an incubator where significant value was both created and experienced by the nascent co‐creator on the current project, with value amplified on and for future co‐creation projects in which they would be engaged. Developing a coalition of partners over the long term is important for making value co‐creation a normal mode of operation.

-

▪

Value co‐creation is a flexible approach and can be used in combination with other conceptual frameworks to develop and deliver education and other resources, products and services. For instance, we combined user‐centred design, experience‐based co‐design, action learning, adult learning theory, transactional learning, instructional learning theory and e‐learning theory to complement value co‐creation.

-

▪

Be transparent with all parties about the shared purpose and process of value co‐creation, the role of each individual and the importance of working together to jointly create value propositions from inception, so that all parties may benefit from the process and co‐created outcomes. In our experience, value was realised by each party at different points of the co‐creation journey, and individuals and organisations went on to experience value beyond project‐specific co‐creative interactions and activities.

-

▪

Substantial investment in time, resources and planning is required to build co‐creation processes with realistic timeframes, suitable management systems (governance, leadership, communication), and appropriate budgets and resources. Be flexible and invest in stakeholder engagement, networking and collaboration. All this will gradually build a culture of meaningful relationships with those involved and committed to user‐centred design principles.

In Australia, there has been continued work towards enabling system drivers that support and grow mature person‐centred models of care that deliver value‐based care. This requires a collaborative effort from all care providers and a strong role for consumers as active partners in their own care. The use of value co‐creation and user‐centred design approaches at all levels of the health care system — by policy makers, health care organisations, trainers, care providers, other stakeholders and, of course, patients, their families and their carers — offers us the opportunity to jointly create better value for all.

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supporting information

Supplementary materials

Acknowledgements

The Inflammatory Bowel Disease GP Aware Project is supported by funding to Crohn’s and Colitis Australia from the Australian Government Department of Health. The funding covered costs associated with conducting the project, including co‐creation of the suite of educational resources. We acknowledge: the important collaboration and partnership with Crohn’s and Colitis Australia and the Gastroenterological Society of Australia in this project; the general practitioners and gastroenterologists who were involved in the focus groups and surveys and provided input into co‐creation of the educational resources; and the Inflammatory Bowel Disease GP Aware Project Advisory Committee for their leadership, contribution and support. We also acknowledge the contributions of the Brisbane South PHN Person‐Centred Care Programs team to the co‐creation of the education and training resources — specifically, Suzanne Harvey and Anthony Elliott for their commitment and leadership throughout the program, and Tahni Roberts (the Person‐Centred Care Lead) for reviewing the educational resources and supporting their implementation in primary care.

References

- 1. Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K. What is co‐creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. J Bus Res 2018; 84: 196‐205. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K. The co‐creation paradigm. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davey J, Krisjanous J. Integrated health care and value co‐creation: a beneficial fusion to improve patient outcomes and service efficacy. Australas Mark J 2021; 10.1177/18393349211030700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scholz B, Bocking J, Happell B. How do consumer leaders co‐create value in mental health organisations? Aust Health Rev 2017; 41: 505‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McColl‐Kennedy JR, Vargo SL, Danaher TS, et al. Healthcare customer value co‐creation practice styles. J Serv Res 2012; 15: 370‐389. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janamian T, Crossland L, Jackson CL. Embracing value co‐creation in primary care services research: a framework for success. Med J Aust 2016; 204 (7 Suppl): S5‐S11. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2016/204/7/embracing‐value‐co‐creation‐primary‐care‐services‐research‐framework‐success [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, et al. Achieving research impact through co‐creation in community‐based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q 2016; 94: 392‐429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janamian T, Jackson CL, Dunbar JA. Co‐creating value in research: stakeholders’ perspectives. Med J Aust 2014; 201 (3 Suppl): S44‐S46. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2014/201/3/co‐creating‐value‐research‐stakeholders‐perspectives [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gouillart F, Hallett T. Co‐creation in government. Stanford Soc Innovat Rev 2015; Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cook‐Sather A, Bovill C, Felten P. Engaging students as partners in teaching and learning: a guide for faculty. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vargo SL, Maglio PP, Akaka MA. On value and value co‐creation: a service systems and service logic perspective. Eur Manag J 2008; 26: 145‐152. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galvagno M, Dalli D. Theory of value co‐creation: a systematic literature review. Manag Serv Qual 2014; 24: 643‐683. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramaswamy V, Gouillart F. The power of co‐creation: build it with them to boost growth, productivity, and profits. New York: Free Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Durall E, Bauters M, Hietala I, et al. Co‐creation and co‐design in technology‐enhanced learning: innovating science learning outside the classroom. Interact Des Archit J 2020; 42: 202‐226. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dopp AR, Parisi KE, Munson SA, et al. Integrating implementation and user‐centred design strategies to enhance the impact of health services: protocol from a concept mapping study. Health Res Policy Syst 2019; 17: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Still B, Crane K. Fundamentals of user‐centered design: a practical approach. Boca Raton: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bovill C. A co‐creation of learning and teaching typology: what kind of co‐creation are you planning or doing? Int J Stud Part 2019; 3: 91‐98. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leoste J, Tammets K, Ley T. Co‐creation of learning designs: analyzing knowledge appropriation in teacher training programs. EC‐TEL Practitioner Proceedings 2019: 14th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; Delft (The Netherlands), Sept 16–19, 2019. http://ceur‐ws.org/Vol‐2437/paper3.pdf (viewed Apr 2022).

- 19. Bovill C, Cook‐Sather A, Felten P, et al. Addressing potential challenges in co‐creating learning and teaching: overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student–staff partnerships. High Educ 2016; 71: 195‐208. [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Gemert‐Pijnen JE, Nijland N, van Limburg M, et al. A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13: e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shivers‐McNair A, Phillips J, Campbell A, et al. User‐centered design in and beyond the classroom: toward an accountable practice. Comput Compos 2018; 49: 36‐47. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Timmerman JG, Tönis TM, Dekker‐van Weering MG, et al. Co‐creation of an ICT‐supported cancer rehabilitation application for resected lung cancer survivors: design and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Australian Government Department of Health. Inflammatory Bowel Disease National Action Plan 2019. Canberra: Department of Health, 2019. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐strategic‐action‐plan‐for‐inflammatory‐bowel‐disease (viewed Apr 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crohn’s and Colitis Australia . Inflammatory bowel disease National Action Plan: literature review 2018. Melbourne: CCA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. International Organization for Standardization . ISO 9241‐210:2019. Ergonomics of human‐system interaction – part 210: human‐centered design for interactive systems. https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html (viewed Apr 2022).

- 26. MacColl Centre for Health Care Innovation; The Commonwealth Fund; Qualis Health. About the Coach Medical Home Project. New York: The Commonwealth Fund, 2013. https://www.coachmedicalhome.org/about (viewed Apr 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard‐Grace R, et al. The 10 building blocks of high‐performing primary care. Ann Fam Med 2014; 12: 166‐171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials