Abstract

In May 1999, field surveys of Lyme disease spirochetes were conducted around the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwestern People's Republic of China. Ixodes persulcatus ticks were obtained in a Tianchi Lake valley with primary forest, while the tick fauna was poor in the semidesert or at higher altitudes in this region. Species identities were confirmed by molecular analysis in which an internal transcribed spacer sequence was used. Of 55 adult ticks, 22 (40%) were positive for spirochetes as determined by Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly culture passages. In addition, some rodents, including Apodemus uralensis (5 of 14 animals) and Cricetulus longicaudatus (the only animal examined), and some immature stages of I. persulcatus (4 of 11 ticks) that had fed on A. uralensis were positive for spirochetes. Based on 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and reactivity with monoclonal antibodies, 35 cultures (including double isolation cultures) were identified as Borrelia garinii (20 isolates, including 9 Eurasian pattern B isolates and 11 Asian pattern C isolates), Borrelia afzelii (10 pattern D isolates), and mixed cultures (5 cultures, including isolates that produced B. garinii patterns B and C plus B. afzelii pattern D). These findings revealed that Lyme disease pathogens are distributed in the mountainous areas in northwestern China even though it is an arid region, and they also confirmed the specific relationship between I. persulcatus and genetic patterns of Borrelia spp. on the Asian continent.

Lyme disease (borreliosis) is the most prevalent tick-borne zoonotic disease (26) in Europe, North America, and eastern Asia. The People's Republic of China, the largest country between Russia and Japan in Asia, is known to have a rich wildlife fauna, and there have been some preliminary reports (1, 23, 27) of this disease in China. Previously, we examined the prevalence of Borrelia spp. in ticks and small field rodents from Inner Mongolia in northeastern China (20) and found that Ixodes persulcatus was a significant vector of two species of Lyme disease spirochetes, Borrelia garinii and Borrelia afzelii, but not of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. However, information concerning the epidemic status of the disease in the northwestern part of China, which is separated from the northeastern part by Mongolia, is inadequate (27). This region is midway along the old Silk Road between Asia and Eastern Europe and midway between the vast deserts and high mountains of Central Asia. The tick fauna in this region is similar, in part, to the tick fauna in northeastern China, far eastern Russia, and the northern half of Japan (19, 22); in particular, I. persulcatus is common in all of these regions. Additionally, the I. persulcatus-related species Ixodes kashmiricus and Ixodes kazakstani have also been found in part of northwestern China (5, 6). Workers should be circumspect in identifying these tick species morphologically.

Here, we describe for the first time a molecular genetic analysis of Lyme disease Borrelia spp. obtained from vector ticks and reservoir rodents in northwestern China and neighboring central Russia, where I. persulcatus and Ixodes ricinus, the two most competent vectors in Eurasia, are both distributed, and discuss the diversity of Lyme disease spirochetes relative to that in other parts of Asia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey sites and field collection.

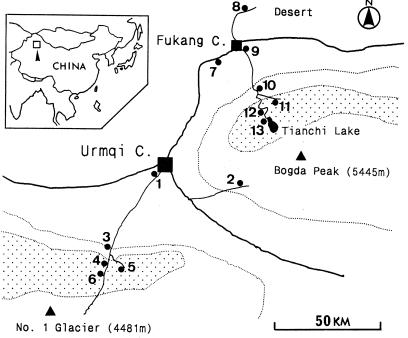

In the second half of May 1999, surveys were made in various environments and at various altitudes around the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Samples were collected at Urumqi City (site 1, vacant lot; site 2, bush); South Valley Pasture, located 60 km south of Urumqi City (site 3, planted poplar and bush; site 4, secondary spruce forest; site 5, bush and spruce forest; site 6, around a horse shed); Fukang City (site 7, poplar windbreak beside desert; site 8, bush in semidesert; site 9, private house); and Tianchi Lake National Park at the foot of Bogda Peak, located 30 km south of Fukang in the Tianshan Mountains (site 10, planted poplar woods in valley; site 11, bush and pasture beside primary forest consisting of trees belonging to the genus Picea; site 12, bush and spruce forest in valley; site 13, primary spruce forest by lake). During the survey period, the daytime temperature varied about 15 to 20°C or more at Tianchi Lake, and the temperature in the South Valley varied about 10 to 20°C. Unfed ticks were collected by flagging the vegetation as we walked through the forest or fields at the sites. During the time that the flagging was occurring, small rodents were captured by using live box traps for one night in each of the downtown or village areas and for two nights in each of the mountainous field areas, and fed immature ticks were recovered from rodents.

FIG. 1.

Survey sites (solid circles) in the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwestern China. The sites are described in Table 1. The thick solid line is the main road (old Silk Road); the area inside the dotted line is the mountainous area; and the dotted area is primary spruce forest.

TABLE 1.

Isolation of Borrelia spp. from ticks and rodents in the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwestern China

| Area | Sitea | Altitude (m)b | Collection | Species | No. examinedc | No. of strains isolated (designation[s]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urmqi City downtown | 1 | 1,000 | Trapping | Mus musculus | 2 | —d |

| South Valley Pasture | ||||||

| Spruce forest | 4 | 1,800 | Trapping | Apodemus uralensis | 8 | — |

| Alticola roylei | 1 | |||||

| Horse shed | 6 | 2,000 | Trapping | Mus musculus | 8 | — |

| Fukang City | ||||||

| Windbreak | 7 | 600 | Flagging | Dermacentor pavlovskyi | 1F | — |

| Semidesert | 8 | 600 | Trapping | Euchoreutes naso | 14 | — |

| Downtown | 9 | 700 | Trapping | Rattus norvegicus | 7 | — |

| Fed tick | Dermacentor sp. | 1L | — | |||

| Tianchi Lake National Park | ||||||

| Village | 10 | 1,200 | Trapping | Rattus norvegicus | 8 | — |

| Crocidura sp. | 1 | — | ||||

| White Poplar Valley | 11 | 1,300 | Trapping | Apodemus uralensis | 5 | — |

| Cricetulus longicaudatus | 1 | 1 (CTC1) | ||||

| Flagging | Ixodes persulcatus | 26M, 29F | 22 (CT1p to CT22p) | |||

| Rock Gate | 12 | 1,500 | Trapping | Apodemus uralensis | 9 | 5 (CTA1 to CTA5) |

| Fed tick | Ixodes persulcatus | 10L, 1N | 4 (CT23p to CT26p) | |||

| Dryomys nitedula | 1 | — | ||||

| Flagging | Dermacentor pavlovskyi | 2F | — | |||

| Lakeside | 13 | 2,000 | Trapping | Apodemus uralensis | 2 | — |

No collection occurred at site 2 (Tianshan Pasture, 1,500 m), site 3 (village, 1,400 m), and site 5 (South Terrace, 1,800 m).

Altitude above sea level.

M, male; F, female; N, nymph, L, larva.

—, no strain isolated.

Identification of ticks and rodents.

Ticks were morphologically identified by using monographs published in Asia (19, 22, 25), and part of each tick was used for species identification by phylogenetic analysis with an internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) sequence between the 5.8S and 28S rRNA genes (7). The small rodents captured were identified by using some Chinese monographs (4, 10, 24).

Spirochete isolation.

Live field-collected and rodent-fed ticks were used for spirochete isolation. The ticks were surface cleaned in a solution containing 3% hydrogen peroxide and then dipped in 70% ethanol for a few minutes. Internal organs dissected in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly II (BSK II) medium (3) were transferred to tubes containing BSK II medium. The cultures were then incubated at 32°C and examined for spirochetes by dark-field microscopy once each week for 7 weeks. Small rodents were screened by BSK II medium culturing of small pieces of tissue punched from ear lobes after the surfaces were wiped with 70% ethanol. The spirochete isolates were propagated and purified in subcultures, and a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was performed for genetic classification.

PCR and RFLP analysis of 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer.

Primers corresponding to the 3′ end of the 5S rRNA gene (rrf) (5′-CTG CGA GTT CGC GGG AGA-3′) and the 5′ end of the 23S rRNA gene (rrl) (5′-TCC TAG GCA TTC ACC ATA-3′), as described previously (13, 17), were synthesized by a custom oligonucleotide synthesis service (Bex Co., Tokyo, Japan). Two-milliliter aliquots of cultures were washed, and the cells were resuspended in 100 ml of water. The resultant cell suspensions were boiled at 100°C for 10 min. A PCR was performed by the method described previously (17). The amplification products of 5S-23S rRNA amplicons were digested with MseI and DraI, and the digested DNA were electrophoresed through 16% polyacrylamide gels. DNA bands were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Sequencing of 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer.

The amplicons of the intergenic spacer sequence (ca. 250 bp) were cloned into the pGEM-T vector, and the recombinant plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli JM109 by using the pGEM-T vector system (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The recombinant plasmids were extracted from E. coli cultures with a Plasmid midi kit (5 prime-3 prime; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method using a dye terminator Taq cycle sequencing kit with primers M13 (−29) and M13 reverse and a model 373A DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). At least three clones were sequenced for each strain.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out as described previously (14). Ten micrograms of protein solution was applied to each lane of each 12.5% polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Antigens were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and specific antigen bands were subsequently detected by immunostaining with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (diluted 1:50 to 1:100) of hybridoma supernatants. The mAbs used were mAb P31d, which reacts with OspA of B. afzelii (2); mAb P3134, which reacts with both OspA and OspB of B. garinii strains that generate RFLP pattern C (12); and mAb D6, which reacts with a 12-kDa protein of B. garinii (15).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of Borrelia strains CTA1b, CT13p, CTA4a, CT7p, CT9p, and CTA3 determined in this study have been deposited under accession numbers AB035960, AB035961, AB035962, AB035963, AB035964, and AB035965, respectively. The accession numbers for the sequences of strains 172 and 173 of I. persulcatus are AB032834 and AB032835, respectively (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank).

RESULTS

Isolation of Borrelia spp. from ticks and rodents.

We made an effort to collect ticks and rodents mainly from the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains, where the primary spruce forests are preserved; in contrast, the southern slopes lack forests. Many isolates were obtained only in the valley (1,300 to 1,500 m above sea level) approaching Tianchi Lake (Table 1); at site 11, I. persulcatus adults were collected by flagging, and 22 of the 55 ticks examined (40%) were positive for spirochetes, as was one Cricetulus longicaudatus. Although no I. persulcatus adults were obtained by flagging at site 12, five of nine Apodemus uralensis (called Apodemus sylvaticus in Chinese literature) obtained there were positive for spirochetes, and one nymph and three larvae of I. persulcatus that had fed on spirochete-positive A. uralensis also were positive. However, spirochetes were not isolated from material obtained in city areas and semidesert and also were not found at higher altitudes (more than 1,800 m) in the South Valley and Tianchi Lake side of the mountains.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of I. persulcatus.

Two of the I. persulcatus adults collected were examined to confirm the accuracy of the morphological identification by molecular phylogenetic analysis. The ticks collected in the Tianshan Mountains had smaller bodies and a coxal spur (data not shown) compared with the ticks found in eastern Asia, including northeastern China (20), and they exhibited higher levels of similarity (96.5 to 99.0%) to I. persulcatus in Japan; however, they were differentiated from some related tick species by the ITS2 sequence similarity matrix (Table 2). Thus, our identification of the Tianshan ticks is reasonable despite the morphological variations.

TABLE 2.

Similarity matrix for internal transcribed spacer sequences of I. persulcatus

| Taxona | % Similarity

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I. persulcatus

|

I. pavlovskyi | I. nipponensis | I. ricinus | I. asanumai | |||||

| 172 | 173 | AH | HN | ON | |||||

| I. persulcatus 172 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 97.1 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 82.5 | 87.6 | 63.4 | 67.4 |

| I. persulcatus 173 | 100.0 | 96.5 | 98.6 | 98.5 | 82.2 | 87.1 | 63.4 | 67.2 | |

| I. persulcatus AH | 100.0 | 96.7 | 96.5 | 84.4 | 87.3 | 62.4 | 67.2 | ||

| I. persulcatus HN | 100.0 | 97.5 | 82.6 | 87.6 | 64.0 | 67.8 | |||

| I. persulcatus ON | 100.0 | 82.9 | 87.1 | 63.6 | 67.4 | ||||

| I. pavlovskyi from Japan | 100.0 | 82.0 | 64.8 | 64.8 | |||||

| I. nipponensis from Korea | 100.0 | 61.6 | 67.9 | ||||||

| I. ricinus from Europe | 100.0 | 56.7 | |||||||

| I. asanumai from Japan | 100.0 | ||||||||

I. persulcatus 172 and 173 are specimens collected in this study; AH, HN, and ON are specimens collected in Japan.

Identification of isolates.

Table 3 shows the results of our identification of Borrelia species by 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer–RFLP analysis. An approximately 250-bp amplicon was obtained from all isolates with the primer set for the intergenic spacer sequence. Most isolates generated patterns B′/B, patterns C′/C, or patterns D′/D when they were digested with DraI and MseI, respectively. Strains that generated patterns B and C were identified as the B. garinii Eurasian type, which is found in Europe and Asia, and the B. garinii Asian type, which is found in Asia but not in Europe, respectively. Strains that generated pattern D were classified as B. afzelii. Furthermore, mixtures of two or three different RFLP patterns (patterns B and C; patterns B and D; patterns B, C, and D) that might have resulted from multiple cultured Borrelia spp. were found (strains CTA1a, CT3p, CT20p, CT21p, and CT22p). To estimate fragment sizes, the intergenic spacer sequences of representative strains CTA1b, CT13p, CTA4a, CT7p, CT9p, and CTA3 were determined. Strains CTA4a, CT7p, and CT9p, which produced RFLP pattern C, generated three fragments (144, 57, and 52 bp) and four fragments (107, 57, 51, and 38 bp) when they were digested with DraI and MseI, respectively; these results are identical to those obtained for B. garinii ASF isolated from Apodemus speciosus in Japan (13). On the other hand, the fragment sizes obtained from amplicons of strains CTA1b and CT13p were very similar, but not identical, to those of B. garinii 20047 and NP81 (13, 17). Likewise, the RFLP pattern of strain CTA3 was similar to the B. afzelii VS461 pattern.

TABLE 3.

RFLP analysis of the 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer and reactivity with mAbs

| Strain(s) | Taxon(a) | Source | 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer

|

Reactivity with mAbs

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplicon size (bp) | DraI pattern (band positions [bp]) | MseI pattern (band positions [bp]) | P31d (OspA) | P3134 (OspA/OspB) | D6 (12-kDa protein) | |||

| CTA1b | B. garinii | A. uralensis | 253 | B′ (201, 52) | B (107, 95, 51) | + | −/+ | + |

| CTA5a, CTA5b | B. garinii | A. uralensis | ca. 250 | B′ | B | + | −/+ | + |

| CT10p, CT23p, CT24p, CT25p, CT26p | B. garinii | I. persulcatus | ca. 250 | B′ | B | + | −/+ | + |

| CT13p | B. garinii | I. persulcatus | 251 | B′ (199, 52) | B (107, 93, 51) | + | −/+ | + |

| CTC1 | B. garinii | C. longicaudatus | ca. 250 | C′ | C | NTa | NT | NT |

| CTA4a | B. garinii | A. uralensis | 253 | C′ (144, 57, 52) | C (107, 57, 51, 38) | − | +/+ | + |

| CT1p, CT2p, CT4p, CT11p, CT15p, CT19p | B. garinii | I. persulcatus | ca. 250 | C′ | C | − | +/+ | + |

| CT5p | B. garinii | I. persulcatus | ca. 250 | C′ | C | + | +/+ | + |

| CT7p, CT9p | B. garinii | I. persulcatus | 253 | C′ (144, 57, 52) | C (107, 57, 51, 38) | − | +/+ | + |

| CTA3 | B. afzelii | A. uralensis | 246 | D′ (17, 52, 20) | D (107, 68, 51, 20) | + | −/+ | − |

| CTA2, CTA4b | B. afzelii | A. uralensis | ca. 250 | D′ | D | + | −/+ | − |

| CT6p, CT8p, CT12p CT14p, CT16p, CT17p, CT18p | B. afzelii | I. persulcatus | ca. 250 | D′ | D | + | −/+ | − |

| CTA1a | B. garinii, B. afzelii | A. uralensis | ca. 250 | B′ + D′ | B + D | NT | NT | NT |

| CT3p, CT20p, CT21p | B. garinii, B. garinii | I. persulcatus | ca. 250 | B′ + C′ | B + C | NT | NT | NT |

| CT22p | B. garinii, B. garinii, B. afzelii | I. persulcatus | ca. 250 | B′ + C′ + D′ | B + C + D | NT | NT | NT |

NT, not tested.

For species identification based on immunological characteristics, the reactivities of isolates were examined by Western blotting using species-specific mAbs. The mAb P31d, which is specific for OspA of B. afzelii and also reacts with some B. garinii strains, reacted with strains identified as B. afzelii. These strains did not react with mAb D6, which is specific for B. garinii. All strains identified as B. garinii reacted with mAb D6, which is specific for B. garinii, and some of these strains also reacted with P31d. The mAb P3134 has the unique ability to react with both OspA and OspB of the B. garinii Asian type (RFLP pattern C). All isolates identified as B. garinii Asian type reacted with the mAb and produced both OspA and OspB bands. OspB of other isolates also reacted with this mAb, but OspA did not. These observations were in agreement with the identification results based on RFLP analysis.

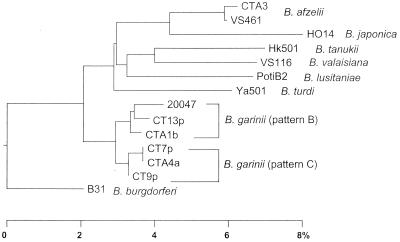

Figure 2 shows a phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer sequences. The sequences of strains CTA1b, CT13p, CTA4a, CT7p, and CT9p exhibited higher levels of similarity (96.8 to 98.8%) to the sequence of B. garinii 20047 (pattern B) and formed the B. garinii cluster. Strain CTA3, identified as B. afzelii, exhibited greater similarity to B. afzelii VS461 (99.6%), and these strains clustered together. In contrast, the levels of similarity to other species were less than 92.3%. The results indicated that our identification of the isolates based on RFLP analysis of intergenic spacer sequences was accurate.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer sequences. The sequences of strains CTA1b, CT13p, CTA4a, CT7p, CT9p, and CTA3 were determined in this study (see text). Previously published sequences of the following strains were also used (accession numbers are in parentheses): strains VS116 (L30134), B31 (L30127), 20047 (L30119), VS461 (L30135), HO14 (L30128), Hk501 (D84404), Ya501 (D84407), and PotiB2 (L30131). The bar indicates levels of sequence dissimilarity.

DISCUSSION

Most of the region in northwestern China which we studied is devoid of plants and is always dry, which restricted our collecting activities to narrow areas of bush or forest along the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains, which are moistened by snow carried on northerly winds. I. persulcatus was obtained in the valley of Tianchi Lake, while the tick fauna was generally poor in areas not covered by plants or in semidesert. The identity of the tick I. persulcatus was determined by a phylogenetic method despite morphological differences from the tick specimens found in other countries (19, 21, 25). Thus, because of this finding, the relationship between morphological classification and phylogenetic classification for the I. persulcatus-related species I. kashmiricus and I. kazakstani found in the central Asia region (5, 6) may need to be reexamined. Based on the present field observations, we speculate that the immature stages of I. persulcatus feed on small rodents at moderate altitudes and the adult stage seeks pastured sheep and cattle and that this tick may find it difficult to survive at altitudes higher than about 1,800 m. In this study, I. persulcatus was not found in either the high-altitude South Valley or the Tianchi Lake area, and the rodents in these locations were also negative for Borrelia spp. Nevertheless, it is interesting that the prevalence of Borrelia spp. in ticks was as high as 40% at the endemic site and that members of the genus Apodemus, the common wood mouse genus, may be the most competent reservoir, like Apodemus spp. in other parts of East Asia, including Japan.

The isolates obtained in this survey were characterized by RFLP analysis and reactivity with mAbs. Of 35 cultures obtained from ticks and rodents, 20 and 10 were identified as B. garinii and B. afzelii, respectively, but no B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates were found. Thus, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto may not occur in northwestern China, and a preliminary description of B. burgdorferi from central China (23) may have been a description of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. Of the cultures identified as B. garinii, 9 and 11 were classified as the Eurasian and Asian types, respectively, and these identities were supported by the sequence homology values obtained for some representative isolates and the reactivities with specific mAbs. The remaining five cultures were cultures of multiple Borrelia isolates from ticks and rodents that were infected with two or more Borrelia species. Cultures of multiple Borrelia isolates were frequently found in surveys conducted in far eastern Russia (11, 18) and northeastern China (9). The Lyme Borrelia species found in our survey areas seem to resemble those isolated from I. persulcatus collected in Hokkaido, Japan (16), in far eastern Russia (11, 18), and in northeastern China (16). In particular, B. garinii isolates that produce RFLP pattern C (Asian type) are obtained only from I. persulcatus and not from I. ricinus in the European region, which supports our speculation (11) concerning the specific relationship between the vector tick I. persulcatus and the RFLP pattern (B. garinii patterns B and C and B. afzelii pattern D). However, two unique RFLP patterns, B. garinii pattern R (found only in the Far East, including Japan) (8, 9) and B. afzelii pattern N (found only in Japan) (11), were not found in this survey. This suggests that Borrelia diversity in northwestern China near Central Asia may differ slightly from Borrelia diversity in the far eastern regions of Asia. To clarify this, additional material, including ticks that feed on birds, must be examined, as reported previously (8).

Since our survey revealed that two well-known pathogens of Lyme disease are distributed in the mountainous forests of northwestern China, further studies are needed to determine the epidemiological and clinical importance of the disease in this region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Ohtake (Miyagi Agricultural College, Sendai, Japan) for help with the survey and T. Wen (Shanghai Medical University, Shanghai, People's Republic of China) for helpful information concerning literature.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for International Cooperative Research 08044310, 0804118, and 10041204 from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ai C, Hu R, Hyland K E, Wen Y, Zhang Y, Qiu Q, Li D, Liu X, Shi Z, Zhao J, Cheng D. Epidemiological and aetiological evidence for transmission of Lyme disease by adult Ixodes persulcatus in an endemic area in China. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:1061–1065. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.4.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranton G, Postic D, Girons I S, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J C, Grinont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G, Burgdorfer W, Hayes S F, Peter O, Aescheliman A. Isolation of a cultivable spirochete from I. ricinus of Switzerland. Curr Microbiol. 1983;8:123–126. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Editorial Committee of the Distribution Mammalian Species in China. Distribution of mammalian species in China. Beijing, People's Republic of China: China Forestry Publishing House; 1997. p. 251. .(In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filippova N A. Taiga tick, Ixodes persulcatus (Acarina: Ixodidae). Morphplogy, systematics, ecology, medical importance. Leningrad, Russia: Soviet Committee for the UNESCO Programme Man and Biosphere; 1985. p. 416. . (In Russian.) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippova, N. A. 1999. Systematic relationships of the Ixodes ricinus complex in the palearctic faunal region, p. 355–361. In G. R. Needham, R. Mitchell, D. J. Horn and W. C. Welbourn (ed.), Acarology IX, vol. 2. Symposium. Ohio Biological SurveyColumbus, Ohio.

- 7.Fukunaga M, Yabuki M, Hamase A, Oliver J H, Jr, Nakao M. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of ixodid ticks based on the ribosomal DNA spacer, internal transcribed spacer 2, sequences. J Parasitol. 2000;86:38–43. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0038:MPAOIT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishiguro F, Takada N, Masuzawa T, Fukui T. Prevalence of Lyme disease Borrelia spp. in ticks from migratory birds on the Japanese mainland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:982–986. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.982-986.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, Masuzawa T, Takada N, Ishiguro F, Fujita H, Iwaki A, Wang H, Wang J, Kawabata M, Yanagihara Y. Lyme disease Borrelia species in northeastern China resemble those isolates from far eastern Russia and Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2705–2709. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2705-2709.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Y, Wang F, Jin S, Li S. Glires (rodents and lagomorphs) of northern Xinjiang and their zoogeographical distribution. Beijing, People's Republic of China: Science Press of Academia Sinica; 1987. p. 274. . (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masuzawa T, Iwaki A, Sato Y, Miyamoto K, Korenberg E I, Yanagihara Y. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolated in far eastern Russia. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuzawa T, Kaneda K, Suzuki H, Wang J, Yamada K, Kawabata H, Johnson R C, Yanagihara Y. Presence of common antigenic epitope in outer surface protein (Osp) A and OspB of Japanese isolates identified as Borrelia garinii. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:455–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masuzawa T, Komikado T, Iwaki A, Suzuki H, Kaneda K, Yanagihara Y. Characterization of Borrelia sp. isolated from Ixodes tanuki, I. turdus, and I. columnae in Japan by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;142:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masuzawa T, Okada Y, Yanagihara Y, Sato N. Antigenic properties of Borrelia burgdorferi isolated from Ixodes ovatus and Ixodes persulcatus in Hokkaido, Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1568–1573. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1568-1573.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuzawa T, Wilske B, Komikado T, Suzuki H, Kawabata H, Sato N, Muramatsu K, Sato N, Isogai E, Isogai H, Johnson R C, Yanagihara Y. Comparison of OspA-serotypes for Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from Japan, Europe and North America. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:539–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakao M, Miyamoto K, Fukunaga M. Lyme disease spirochetes in Japan: enzootic transmission cycles in birds, rodents, and Ixodes persulcatus ticks. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:878–882. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A D, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato Y, Miyamoto K, Iwaki A, Masuzawa T, Yanagihara Y, Korenberg E I, Gorelova N B, Volkov V I, Ivanov L I, Liberova R N. Prevalence of Lyme disease spirochetes in Ixodes persulcatus and wild rodents in far eastern Russia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3887–3889. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3887-3889.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takada N. A pictorial review of medical acarology in Japan. Kyoto, Japan: Kinpodo; 1990. p. 216. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takada N, Ishiguro F, Fujita H, Wang H, Wang J, Masuzawa T. Lyme disease spirochetes in ticks from northeastern China. J Parasitol. 1998;84:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takada N, Ishiguro F, Iida H, Yano Y, Fujita H. Prevalence of Lyme Borrelia in ticks, especially Ixodes persulcatus (Acari: Ixodidae), in central and western Japan. J Med Entomol. 1994;31:474–478. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng K F. Economic insect fauna of China, fascicle XV. Acarina Ixodoidea. People's Republic of China: Science Press of Academia Sinica, Beijing; 1978. p. 174. . (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wanchun T, Zhang Z, Moldenhauer S, Guo Y, Yu Q, Wang L, Chen M. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi from ticks (Acari) in Hebei Province, China. J Med Entomol. 1998;35:95–98. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S, Yang G. Rodentia fauna of Xinjiang. People's Republic of China: Xinjiang People's Publishing House, Urumqi; 1983. p. 223. . (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguti N, Tipton V J, Keegan H L, Toshioka S. Ticks of Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. Brigham Young Univ Sci Bull Biol Ser. 1971;15:142–148. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanagihara Y, Masuzawa T. Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis) FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:249–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z. Epidemiological features of Lyme disease in China. In: Yanagihara Y, Masuzawa T, editors. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Lyme Disease in Japan. Shizuoka, Japan: University of Shizuoka; 1994. pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]