Abstract

We report a case of bacteremia caused by Bacillus subtilis variant natto after a gastrointestinal perforation in a patient in Japan. Genotypic and phenotypic studies of biotin identified B. subtilis var. natto. This case and 3 others in Japan may have been caused by consuming natto (fermented soybeans).

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis var. natto, bacteremia, gastrointestinal origin, bacteria, Japan

Bacillus subtilis is a gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium temporarily present in the human gastrointestinal tract (1). The presence of B. subtilis in clinical specimens indicates contamination, but rare cases of bacteremia have been reported in Japan (2). Previous reports have attributed bacteremia in Japan to gastrointestinal origin but of unknown cause. We identified a case of B. subtilis variant natto bacteremia in a patient in Japan.

In May 2021, a 56-year-old woman was referred to the Japanese Red Cross Musashino Hospital (Musashino-shi, Tokyo, Japan) for a 2-day history of abdominal pain after having taken barium for gastric radiographic examination. The patient had a history of hypertension and ate natto (fermented soybeans) almost every day. At admission, the patient exhibited spontaneous abdominal pain, muscular defense, and rebound tenderness. Laboratory findings showed a decreased leukocyte count (1,800 cells/µL, reference range 3,300–8,600 cells/µL) and mildly increased C-reactive protein concentration (0.75 mg/dL, reference range 0–0.14 mg/dL). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed contrast accumulation in the colon and free air around the sigmoid rectum. Lower gastrointestinal perforation and generalized peritonitis were suspected, and 2 sets of blood cultures were obtained. Emergency proctosigmoidectomy (Hartmann surgery) was performed on the same day, and perforation of the sigmoid colon was confirmed.

Intravenous antimicrobial treatment was initiated. Initial treatment was piperacillin/tazobactam (18 g/d). On day 5, because both blood culture sets were positive for gram-positive rod bacteria, teicoplanin (800 mg/d) was added. On day 11, only B. subtilis was isolated from the culture by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry, and the antimicrobial drugs were changed to ampicillin/sulbactam (12 g/d) as indicated by antimicrobial susceptibility testing by broth microdilution (Appendix Table). B. subtilis was also detected along with multiple other bacteria by culture of ascites fluid collected intraoperatively. After 39 days of antimicrobial therapy, the patient was discharged.

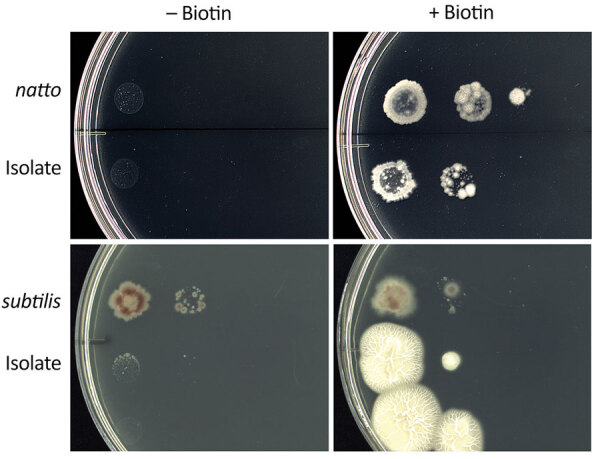

We investigated whether the blood culture isolate was B. subtilis var. natto. DNA analysis showed that in the bioF region, the isolate was 100% homologous to the B. subtilis var. natto standard strain. Compared with the B. subtilis subspecies subtilis standard strain, the isolate had ≈50 fewer bases and the bioW region of the isolate had a single-nucleotide mutation that resulted in a termination codon for amino acid synthesis (Appendix Figures 1–4). The isolate and B. subtilis var. natto standard strain grew abundantly on a biotin-supplemented medium but did not thrive on a nonsupplemented medium (Figure).

Figure.

Bacillus subtilis cultures on E9 minimal medium agar plates with and without biotin. From left to right in each column, 0.5 McFarland standard was diluted ×1, ×10, and ×102, and 10 μL was incubated at 35°C for 72 hours under aerobic conditions. The isolate showed a biotin requirement. Isolate, Bacillus subtilis variant natto from patient in Japan with bacteremia of gastrointestinal origin; natto, B. subtilis var. natto standard strain; subtilis, B. subtilis subspecies subtilis standard strain.

Our biotin gene and biotin requirement testing confirmed that the isolate in this case was B. subtilis var. natto. Previous genotypic and phenotypic studies on biotin were helpful in identifying this variant. Kubo et al. reported that natto-fermented B. subtilis requires biotin and that nonfermented B. subtilis does not (3). bioF and bioW are biotin biosynthetic operons in B. subtilis (4). Compared with the B. subtilis subsp. subtilis standard strain, the 2 biotin genes of the isolate in this study and the B. subtilis var. natto standard strain were partially defective. According to the biotin requirement test, the isolate required biotin.

We conclude that this case of bacteremia caused by B. subtilis var. natto resulted from a gastrointestinal perforation. In Japan, the most common causative organism of community-acquired bloodstream infections is gram-negative Escherichia coli (25.4%); gram-positive bacilli rarely induce bacteremia (2.7%) (5). B. subtilis bacteremia typically originates from the gastrointestinal tract (2); Tamura et al. have reported 3 cases of B. subtilis bacteremia arising from the gastrointestinal tract (6). In patients with gastrointestinal bacteremia, the causative organism differs according to the food consumed (7). Oggioni et al. reported a case of B. subtilis bacteremia caused by probiotics (8). However, the patient that we report was not taking any probiotics but frequently ate natto. Most of the previously reported cases of B. subtilis bacteremia in Japan (2,6) were possibly related to natto consumption, although dietary history was not mentioned in their reports.

This case of bacteremia caused by B. subtilis var. natto resulted from gastrointestinal tract perforation. Genotypic and phenotypic studies on biotin effectively identified B. subtilis var. natto. In Japan, natto consumption is common, and B. subtilis bacteremia of gastrointestinal origin is most likely associated with B. subtilis var. natto.

Supplemental results from study of patient with Bacillus subtilis variant natto bacteremia of gastrointestinal origin, Japan.

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinical staff at the Japanese Red Cross Musashino Hospital for their dedicated clinical practice and patient care.

Biography

Mr. Tanaka is a pharmacist at the Japanese Red Cross Musashino Hospital in Musashino-shi, Tokyo, Japan. His main research interest is microbiology.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Tanaka I, Kutsuna S, Ohkusu M, Kato T, Miyashita M, Moriya A, et al. Bacillus subtilis variant natto bacteremia of gastrointestinal origin, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022 Aug [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2808.211567

References

- 1.García-Arribas ML, de la Rosa MC, Mosso MA. [Characterization of the strains of Bacillus isolated from orally administered solid drugs] [in French]. Pharm Acta Helv. 1986;61:303–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashimoto T, Hayakawa K, Mezaki K, Kutsuna S, Takeshita N, Yamamoto K, et al. Bacteremia due to Bacillus subtilis: a case report and clinical evaluation of 10 cases [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2017;91:151–4. 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi.91.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubo Y, Rooney AP, Tsukakoshi Y, Nakagawa R, Hasegawa H, Kimura K. Phylogenetic analysis of Bacillus subtilis strains applicable to natto (fermented soybean) production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6463–9. 10.1128/AEM.00448-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki M, Kawamura F, Kurusu Y. Genetic analysis of an incomplete bio operon in a biotin auxotrophic strain of Bacillus subtilis natto OK2. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2004;68:739–42. 10.1271/bbb.68.739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshita N, Kawamura I, Kurai H, Araoka H, Yoneyama A, Fujita T, et al. Unique characteristics of community-onset healthcare- associated bloodstream infections: a multi-centre prospective surveillance study of bloodstream infections in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2017;96:29–34. 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura T, Yoshida J, Kikuchi T. Bacillus subtilis bacteremia originated from gastrointestinal perforation: report of 3 cases [in Japanese]. Journal of the Japan Society for Surgical Infection. 2020;5:456. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosoya S, Kutsuna S, Shiojiri D, Tamura S, Isaka E, Wakimoto Y, et al. Leuconostoc lactis and Staphylococcus nepalensis Bacteremia, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2283–5. 10.3201/eid2609.191123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oggioni MR, Pozzi G, Valensin PE, Galieni P, Bigazzi C. Recurrent septicemia in an immunocompromised patient due to probiotic strains of Bacillus subtilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:325–6. 10.1128/JCM.36.1.325-326.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental results from study of patient with Bacillus subtilis variant natto bacteremia of gastrointestinal origin, Japan.