Abstract

Background:

The fast and accurate diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is critical to reducing the spread of disease. Although commercial genotypic drug-susceptibility tests (DST) are close to the goal, they are still not able to detect all relevant DR-TB related mutations. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) allows better comprehension of DR-TB with a great discriminatory power. We aimed to evaluate WGS in M. tuberculosis isolates compared with phenotypic and genotypic DST.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study evaluated 30 isolates from patients with detected DR-TB in Brazil and Mozambique. They were evaluated with phenotypic (MGIT-SIRE™) and genotypic (Xpert-MTB/RIF™, Genotype-MTBDRplus™, and MTBDRsl™) DST. Isolates with resistance to at least one first- or second-line drug were submitted to WGS and analyzed with TB profiler database.

Results:

WGS had the best performance among the genotypic DST, compared to the phenotypic test. There was a very good concordance with phenotypic DST for rifampicin and streptomycin (89.6%), isoniazid (96.5%) and ethambutol (82.7%). WGS sensitivity and specificity for detection resistance were respectively 87.5 and 92.3% for rifampicin; 95.6 and 100% for isoniazid; 85.7 and 93.3% for streptomycin while 100 and 77.2% for ethambutol. Two isolates from Mozambique showed a Val170Phe rpoB mutation which was neither detected by Xpert-MTB/RIF nor Genotype-MTBDRplus.

Conclusion:

WGS was able to provide all the relevant information about M. tuberculosis drug susceptibility in a single test and also detected a mutation in rpoB which is not covered by commercial genotypic DST.

Keywords: Drug-resistant tuberculosis, Whole genome sequencing, Next-generation sequencing clinical diagnostics, Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

1. Introduction

In 2016, globally there were an estimated 10.4 million incident cases of tuberculosis (TB), 1.3 million TB-related deaths among HIV-negative and 374.000 deaths among HIV-positive people [1]. Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is increasing and may undermine efforts to eradicate TB in many countries [2]. Global data from 2016 estimated 490.000 new MDR-TB cases and around 50% related deaths. But even so, information about DR-TB in Brazil and Mozambique is scarce, mainly due to the lack of laboratory facilities for drug susceptibility tests (DST) [1]. From 1998 to 2015, the concept of a high-burden country (HBC) became familiar and widely used and widely used in the context of TB, TB-HIV, and multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB). In 2015, Mozambique was among the three lists and Brazil in the former two [1]. New accurate and rapid diagnostic strategies for drug-resistance are urgently required to ensure that patients are diagnosed early and initiated onto appropriate therapy to improve outcomes and prevent the spread of DR bacilli [3-6]. Currently, phenotypic DST is the gold standard for diagnosis of drug resistance. However they are time-consuming, require expensive laboratory facilities, are not available in many HBC and are not standardized for all anti-TB drugs [7-9].

Recently World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed three rapid genetic-based DST: Xpert-MTB/RIF, MTBDRplus, and MTBDRsl line-probe assays [1]. Although these tests are fast and easy to perform, they are not able to detect all the mutations associated with DR-TB [10-12]. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) allows the analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome enabling the identification of mutations which confer resistance, mutations compensating for fitness cost and has an extremely high discriminatory power that to measure the transmission of M. tuberculosis [13-15]. The development of next-generation sequencing technologies has reduced costs and time required to sequence the M. tuberculosis genome, making it progressively more affordable to study the epidemiology of disease as well as to describe the mechanisms of drug resistance [16]. However, the development and standardization of robust platforms that enable reliable analysis and interpretation of WGS data remain to be achieved [8,17,18].

We used WGS to characterize the mutations conferring resistance in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis from Brazil and Mozambique and to compare these results to those obtained by phenotypic and commercial genotypic DST.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and population

This is a cross-sectional study evaluating DR M. tuberculosis isolated from different patients in Southeastern Brazil (São Paulo state) and Central Mozambique (Sofala province). All the isolates were tested with phenotypic, commercial genotypic DST and were submitted to WGS if resistance was detected to at least one first- or second-line drug by one of these tests.

2.2. Drug-susceptibility tests

Phenotypic DST was conducted using MGIT-960 SIRE kit (MGIT-960; Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD). The critical concentrations being 0.10 g/mL for isoniazid (H), 1.0 g/mL for rifampicin (R), 5.0 g/mL for ethambutol (E) and 1.0 g/mL for streptomycin (Sm) [19].

Molecular DST was performed using the Genotype-MTBDRplus 2.0 and MTBDRsl 2.0 (Hain Lifesciences, GmbH, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MTBDRplus evaluates mutations in the rpoB (R resistance); katG and inhA genes (H resistance) [20,21], while the MTBDRsl detects mutations related to resistance to fluoroquinolones (gyrA and gyrB genes mutations) and second-line injectable drugs as capreomycin, amikacin, and kanamycin (rrs and eis gene mutations) [22]. In addition, all the isolates were also tested with Xpert-MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions [23].

2.3. Genomic DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing

The cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-lysozyme method was used for genomic DNA extraction and purification in sub-cultured isolates [24]. The DNA concentrations were measured using Nanodrop and then checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. The WGS was performed using Illumina MiSeq Sequencing System MiSeqV2-500 cycles (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). DNA library was prepared using Nextera XT library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed using MiSeq sequencer reagent kit V2 as per manufacturer's protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) [25], producing paired-end read 2 × 250, with a read length of 500bp. Whole genome sequences were deposited to the European Nucleotide Archive and are available under accession number: PRJEB23648.

2.4. WGS data analysis

Reads with phred quality score ≥30 were mapped with BWA v 0.7.5a (Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Tool) using the M. tuberculosis H37Rv reference genome. Conversion from sequence alignment map (SAM) format sorted, indexed binary alignment map (BAM) files was done using SAM tools (version 0.1.19)26. PCR-duplicates were removed using the Mark Duplicates option of the Picard software tools (version 1.61). The variants were identified with SAMtools/BCFtools v 0.1.18 and annotated with SnpEffv 4.0.

Reads were analyzed with a customized pipeline comprised of open source software as described previously [27]. Briefly, trimmomatic was used to remove adapters and low-quality bases (phred quality score of less than 20) using a sliding window approach, and filtering for a minimum read length of 36 [28]. Trimmed and filtered reads were aligned to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Genbank: AL123456.3) reference genome using three different alignment tools: the BWA [26], Novoalign (Novocraft) and SMALT [29]. The alignment files were subjected to local realignment around insertions and deletions (indels) and de-duplication using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) [30] and Picard Tools [31], respectively. Genomic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms and indels) in coding and non-coding regions were identified from each alignment file using GATK [30] and SAMTools [26]. Variants identified in all three alignments by both GATK and SAM Tools were used for further analysis. Variants were annotated using annotation data from TubercuList [32].

2.5. Genotypic drug resistance prediction from WGS

TB profiler was used to identify mutations known to cause drug resistance [33].

2.6. Phylogenetic analysis

Concatenated sequences containing all high-confidence variable sites (coding and non-coding single nucleotide variants) were used to create a maximum likelihood phylogeny with RaxML using 1000 bootstrap pseudo-replicates [34]. The General time reversal nucleotide substitution model was applied for phylogenetic inference.

2.7. Ethical aspects

IRB approval was got under the protocol number: 17471/2014 in Brazil and 259/CNBS/14 in Mozambique.

3. Results

3.1. Patients' demographic characteristics

Among the 17 patients from Brazil, 15 (88.2%) were male, 16 (94.1%) had a pulmonary disease, and none were co-infected with HIV.One female patient (case #2370) was born in Angola (Africa) and had been living in Brazil for five years when she was diagnosed with extensively drug resistant TB (XDR-TB). Among the 13 patients from Mozambique, seven (53.8%) were male, all presented pulmonary disease and six (46.1%) were co-infected with HIV.

3.2. Phylogenetic results

Among Mozambican isolates, 9 (69.2%) had a lineage of European American (lineage-4); 2 (15.4%) were East Africa/Indian Ocean (lineage-1);1 (7.7%) was Beijing/East Asia (lineage-2); and 1 (7.7%) was Delhi/Central Asia (lineage-3), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Lineage, resistance profile and mutations evidenced by susceptibility tests and WGS of isolates from Mozambique.

| N | MZB Isolate ID |

Lineage | MTBDR plus | MTBDR sl | Xpert | Phenotypic test | Whole genome sequencing | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mut R | Mut H | Mut Fq | Mut iSLD | R | R | H | H | Sm | Mut R | Mut H | Mut Z | Mut E | Mut Sm | Mut iSLD | Mut Fq | Mut PAS | |||

| 1 | 227 | 4.3 | S531L | WT, S315T2 (Kat G) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | ||||||||

| 2 | 243 | 1 | WT8, WT6 | WT2 (inhA) | No | No | No | No | No | embC Thr270lle, embB Glu378Ala | |||||||||

| 3 | 751 | 4.3 | WT, S315T2 (Kat G) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB Val170Phe | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Lys96Arg | embB Met306Val | rpsL Lys43Arg | ||||||

| 4 | 894 | 4.3 | WT, S315T2 (kat G) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | KatG Ser315Thr | rpsL Lys43Arg | |||||||||

| 5 | 964 | 2.2 | WT7, H526D | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | rpoB His445Tyr | ||||||||||

| 6 | 2075 | 4.3 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | KatG Ser315Thr | rpsL Lys43Arg | ||||||||||

| 7 | 2078 | 4.3 | WT, S315T2 (kat G) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB Val170Phe | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Lys96Arg | embB Met306Val | rpsL Lys43Arg | ||||||

| 8 | 2368 | 4.1.1.3 | WT8, S531L | WT, S315T2 (kat G), WT1, T8C (inhA) | WT2, A90V (gyr A) | WT2, C14T (eis) | Yes | Inv | Inv | Inv | Inv | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Arg154Gly | embB Met306Ile | gyrA Ala90Val | |||

| 9 | 2721 | 4.3 | WT7 | WT, S315T2 (kat G) | WT2, A90V (gyr A) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB His445Tyr | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Leu19Arg | embB Gln497Arg | rpsL Lys43Arg | gyrA Ala90Val | |||

| 10 | 2937 | 3 | No | No | Yes | No | No | kasA Gly269Ser | embB Met306Ile | rpsL Lys88Arg | |||||||||

| 11 | 3033 | 4.3 | S531L | WT, S315T2 (kat G) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | embB Gln497Arg | rpsL Lys43Arg | ||||||

| 12 | 3150 | 1 | No | No | No | No | Yes | embC Thr270Ile, embB Glu378Ala | |||||||||||

| 13 | 3185 | 4.3 | WT7 | WT, S315T2 (kat G) | WT2, A90V (gyr A) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB His445Tyr | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Leu19Arg | embB Gln497Arg | rpsL Lys43Arg | gyrA Ala90Val | |||

Mut R: mutations in rpoB gene related to rifampicin resistance; Mut H: mutations related no isoniazid resistance.

Mut Fq: mutations related to fluoroquinolones resistance; Mut iSLD: mutations related to injectable second-line drugs resistance; WT: absence of wild-type band; Xpert R: rifampicin resistance detected by Xpert MTB/RIF; R: rifampicin.

H: isoniazid; E: ethambutol; Sm: streptomycin; Z: pyrazinamide; PAS: para-aminosalicylic acid; NV: not valid phenotypic test.

Regarding Brazilian isolates, 16 (94.1%) were European American (lineage-4), and 1 (5.9%) was Beijing/East Asia (lineage-2) as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lineage, resistance profile and mutations evidenced by susceptibility tests and WGS of isolates from Brazil.

| N | BRA Isolate ID |

Lineage | MTBDR plus | MTBDR sl | Xpert | Phenotypic test | Whole genome sequencing | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mut R | Mut H | Mut Fq | Mut iSLD | R | R | H | H | Sm | Mut R | Mut H | Mut Z | Mut E | Mut Sm | Mut iSLD | Mut Fq | Mut PAS | |||

| 1 | 241 | 4.3 | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | No | No | Yes | No | No | KatG Ser315Thr, KasA Gly269Ser | ||||||||||

| 2 | 536 | 2.2 | WT8, S531L | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | |||||||||||

| 3 | 868 | 4.9 | WT8, S531L | WT2, A90V (gyr A) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | rpoB Ser450Leu | gyrA Ala90Val | ||||||||

| 4 | 1028 | 4.9 | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | No | No | Yes | No | No | KatG Ser315Thr | ||||||||||

| 5 | 1245 | 4.9 | WT7 | WT, S315T1 (kat G), WT (inh A) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | rpoB His445Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | ||||||||

| 6 | 1662 | 4.9 | WT8, S531L | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Ala3Pro | embB Met306Val | rpsL Lys43Arg | |||||

| 7 | 1696 | 4.9 | WT3 | Yes | No | No | No | No | |||||||||||

| 8 | 1804 | 4.3 | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | No | No | Yes | No | No | KatG Ser315Thr, KasA Gly269Ser | ||||||||||

| 9 | 1874 | 4.3 | WT1, C15T (inh A) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | inhA C15T | ||||||||||

| 10 | 2080 | 4.3.2 | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | KatG Ser315Thr | rrs intragenic | |||||||||

| 11 | 2370 | 4.3 | WT8, S531L | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | WT3, D94N/Y (gyr A) | WT1 A1401G (rrs) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Ser104Arg | embB Met306Ile rpsL Lys88Arg, rrs intragenic | rpsL Ly88Argrrs intragenic | rrs intragenic | gyrA Asp94Asn | folC Arg49Gln |

| 12 | 2591 | 4.3 | WT8, S531L | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr, KasA Gly269Ser | pncA Arg140His, pncA Phe94Val | |||||||

| 13 | 2782 | 4.9 | WT2 | WT, C15T (inh A) | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | ||||||||||

| 14 | 2943 | 4.3 | WT3 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | rpoB Ser431Thr | rrs intragenic | rrs intragenic | ||||||||

| 15 | 3052 | 4.3 | S531L | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | ||||||||

| 16 | 3200 | 4.9 | WT8, S531L | WT, S315T1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | rpoB Ser450Leu | KatG Ser315Thr | pncA Ala3Pro | embB Met306Val | rpsL Lys43Arg | |||||

| WT3, A90V, D94G, D94N/Y (gyr A) | gyrA Ala90Val, gyrA Asp94Gly | ||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | 3360 | 4.3 | S531L | WT, S315T1 (kat G) | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | KatG Ser315Thr, KasA Gly269Ser | embB Met306Ile | ||||||||

Mut R: mutations in rpoB gene related to rifampicin resistance; Mut H: mutations related no isoniazid resistance.

Mut Fq: mutations related to fluoroquinolones resistance; Mut iSLD: mutations related to injectable second-line drugs resistance; WT: absence of wild-type band; Xpert R: rifampicin resistance detected by Xpert MTB/RIF; R: rifampicin. H: isoniazid; E: ethambutol; Sm: streptomycin; Z: pyrazinamide; PAS: para-aminosalicylic acid.

3.3. Drugs susceptibility test results

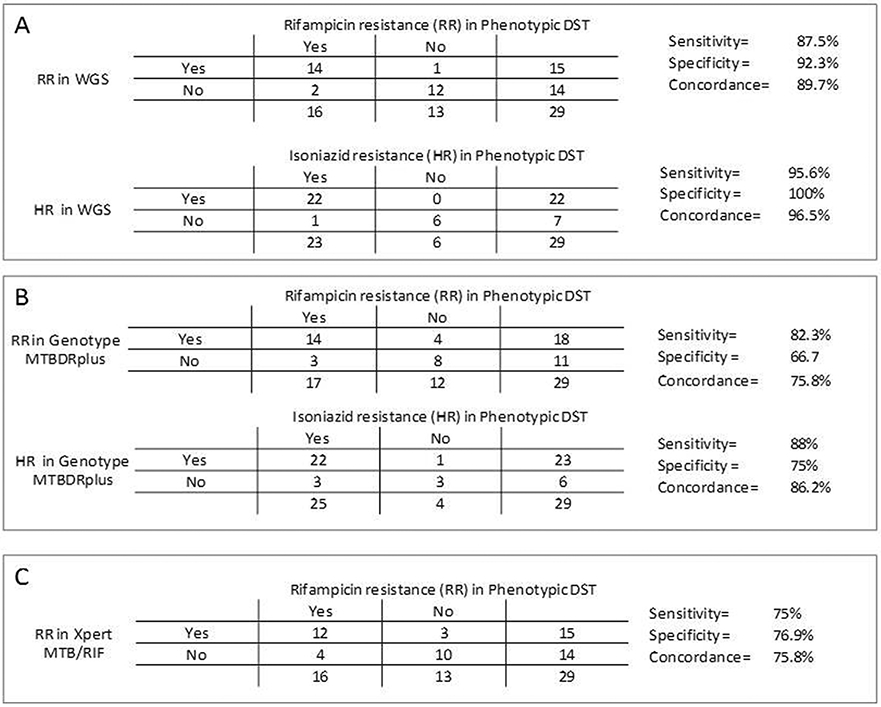

Overall, Genotype-MTBDRplus sensitivity was better than Xpert-MTBDR/RIF for rifampicin (82.3% versus 75%). When compared to WGS the two commercial tests showed the same sensitivity (87.5%). Detection of isoniazid resistance was lower in Genotype-MTBDRplus compared with WGS (88% versus 95.6%). Detailed results of DST including WGS of Mozambique isolates are presented in Table 1, and the Brazil isolates in Table 2.

For all sequenced isolates over 99% of the reference genome was covered by at least one read and an average depth of coverage of 44 (min. 20 - max. 80) was achieved when considering the average depth of coverage for each isolate aligned to M. tuberculosis H37Rv with BWA, Novoalign and SMALT.

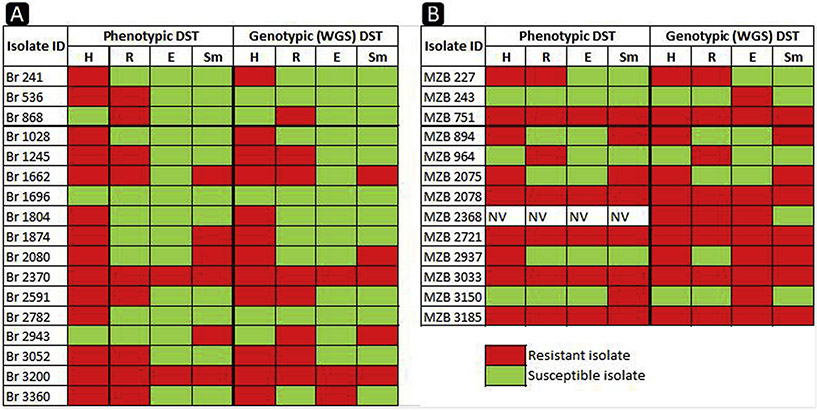

WGS sensitivity and specificity for detecting mutations associated with resistance were respectively: 87.5% and 92.3% for rifampicin; 95.6% and 100% for isoniazid; 85.7% and 93.3% for streptomycin; 100% and 77.2% for ethambutol. The overall concordance of WGS with phenotypic DST was 89.6% for rifampicin and streptomycin; 96.5% for isoniazid and 82.7% for ethambutol (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Heat-map of the resistance profile comparing the phenotypic and WGS DST results. Red color indicates drug resistance and green color indicates drug sensitivity. H: isoniazid; R: rifampicin; E: ethambutol; Sm: streptomycin; NV: not valid phenotypic test. Br: isolates from Brazil, MZB: isolates from Mozambique.

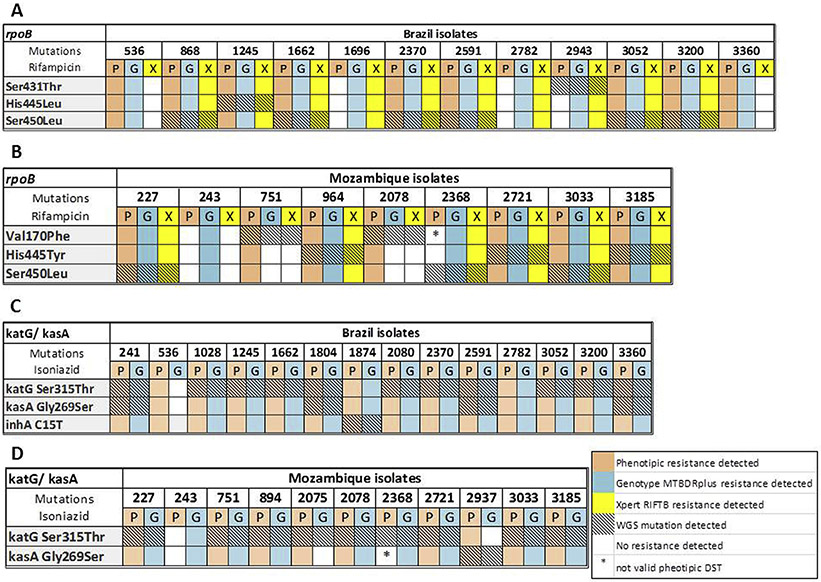

The Xpert-MTB/RIF and Genotype MTBDRplus were not able to detect the mutation Val170Phe present in two isolates from Mozambique (#751 and #2078) and this had an impact on the sensitivity of these two commercial tests.

The 2 × 2 table comparing phenotypic DST with Genotype MTBDRplus, Xpert-MTB/RIF and WGS is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The sensitivity, specificity and concordance between phenotypic DST and WGS (A); phenotypic DST and Genotype MTBDRplus (B); phenotypic DST and Xpert-MTB/RIF (C). RR: rifampicin resistance; HR: isoniazid resistance; WGS: whole genome sequencing.

3.4. Analysis of mutations associated with drug resistance detected by WGS

The most frequent detected mutation related to rifampicin resistance was rpoB Ser450Leu among Brazilian isolates, while rpoB Ser450Leu and rpoB His445Tyr were the most common mutations among Mozambican isolates.

The katG mutation Ser315Thr related to isoniazid resistance was the most frequent in Brazil and Mozambique. An intragenic rrs mutation was the most common mutation associated with streptomycin resistance among Brazilian isolates while the rpsL Lys43Arg was the most frequent mutation among Mozambican isolates. Among all isolates, the most common mutations related to fluoroquinolones resistance was gyrA Ala90Val.

The most frequent mutations related to ethambutol resistance were embB Met306Val, embB Met306lle among Brazilian isolates and embB Gln497Arg among Mozambican isolates. The pncA Ala3Pro was the most frequent mutation among Brazilian isolates, while pncA Lys96Arg and Lys19Arg were the most common among Mozambican isolates.

In Fig. 3 there is the complete information regarding the phenotypic DST, WGS and the commercial DST for all the isolates from Brazil and Mozambique for rifampicin and isoniazid resistance detection.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic and commercial genotypic drug-susceptibility tests (DST) analyzed together with WGS results for rifampicin resistance in Brazil (A) and Mozambique (B) isolates; and for isoniazid resistance in Brazil (C) and Mozambique (D) isolates.

4. Discussion

One of the most important clinical applications of WGS of M. tuberculosis isolates is the prediction of phenotypic drug resistance. However, the confidence at which these predictions are made is dependent on our knowledge of the association between phenotype and genotype [8]. Several studies have investigated the utility of WGS as a tool for DST [13,33,35]. The accuracy of predicting resistance varies among different classes of drugs as well as different drugs from the same class. M. tuberculosis strains with a minimum inhibitory concentration very close to the critical concentration will flip-flop between resistant and susceptible, thereby impacting the predictive value of the mutation causing resistance [8,35,36].

Coll et al., (2015) [33] evaluated isolates from different countries to obtain data of sensitivity and specificity of WGS in predicting drug resistance, also using phenotypic tests as a reference. They found respectively, high sensitivity and specificity values for the first-line drugs: 96.2% and 98.1% for rifampicin; 92.8% and 100% for isoniazid; 88.7% and 81.7% for ethambutol; 87.1% and 89.7% for streptomycin. Walker et al. [13] performed a similar study including isolates from different countries. The sensitivity and specificity values were respectively:91.7% and 99.2% for rifampicin; 85.2% and 98.4% for isoniazid; 82.3% and 95.1% for ethambutol; 81.6% and 99.1% for streptomycin. These results were further supported by Chatterjee et al. [35], who evaluated isolates from India. The sensitivity for predicting resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid was 100%, while the specificity was 94%. For ethambutol, sensitivity was 100% and the specificity around 78%. For streptomycin, sensitivity was 85% and specificity 100%. Our data, as presented by others, reinforce the potential for WGS to be used as a standalone drug resistance.

There was a discrepancy between phenotypic DST and WGS for rifampicin resistance. In two isolates phenotypic DST showed resistance without mutations detected in WGS, and in one isolate the opposite was observed. This might be related the presence of more than one strain in the same clinical sample.

The majority of isolates resistant to rifampicin presented mutations in a well-defined region of 81 base pairs of the rpoB gene, called rifampicin-resistance-determining region (RRDR), and the Ser450Leu is the most frequent mutation associated with resistance to this drug [37,38]. Importantly, two isolates (#751 and #2078) from Mozambique had the rpoB Val170Phe mutation. This mutation is located outside the RRDR and is thus not detected by commercial assays currently being rolled-out at global scale [39]. In this study, we did not identify the rpoB Ile491Phe mutation, which was described in up to 30% of MDR-TB isolates in Swaziland [40].

The molecular basis for isoniazid resistance is more complex than that for rifampicin. Usually, mutations in the katG gene cause high-level isoniazid resistance, whereas those in inhA and kasA result in low-level resistance [41]. katG Ser315Thr was the most common mutation causing isoniazid resistance in this study. In a previous study, we showed that the frequency of katG mutations was higher in the Mozambique (89.4%) compared to the Brazilian isolates (59.5%) [42].

The molecular mechanism of pyrazinamide resistance is largely associated with mutations in the pncA gene. These resistance-causing mutations are distributed throughout the gene, but not all mutations detected in this gene confer resistance. In this study, we identified five different pncA mutations. All of these have been previously reported to confer resistance [43-45]. However, the WHO guidelines suggest the use of pyrazinamide irrespective of DST results given the challenge of phenotypic DST because of the intracellular activity of pyrazinamide against intracellular pathogens and low confidence on the phenotypic DST [14,46].

The main mutations associated with streptomycin resistance occur in the rpsL gene, which confers moderate to high-level drug resistance. Mutations in the rrs gene are associated with moderate levels of resistance [47-50]. Among eight isolates from Mozambique with detected resistance to streptomycin in the phenotypic DST, seven (87.5%) also had resistance to isoniazid, both detected by WGS. Among Brazilian isolates it was similar, with five out of six (83.3%) of the isolates with streptomycin resistance in the phenotypic DST had also resistance to isoniazid, as reported previously [51]. This is probably due to the extensive use of streptomycin when DR-TB was suspected in previous decades.

Most mutations that have been already recognized as associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones are located in a conserved region of the gyrA gene, in codons 90 and 94, which are the most frequently mutated [52]. A previous study of our group reported that 43.7% of 16 DR-TB isolates from Mozambique showed resistance to fluoroquinolones (100% with the mutation gyrA Ala90Val) [53].

As far as we know, this is the first study using WGS in DR M. tuberculosis isolates in Mozambique. In this context, the use of WGS should be of great relevance considering that it allows the simultaneous detection of drug-resistant mutations to the most important existing drugs as well as phylogenetic studies that may help to understand and manage DR-TB. Our group had sequenced two isolates from a single patient who evolved from an MDR-TB status to a pre-XDR profile during treatment [54]. Brazil is a big country and there are many regional differences in circulating M. tuberculosis strain types, so there is a need for further studies using WGS in other regions and populations across the country.

This study amplifies the sample of clinical isolates, and we were able to show that WGS had an excellent performance and should be considered to be used in high burden TB and DR-TB areas around the world. Besides, WGS has other advantages as the turnaround time and the possibility to identify the presence of heteroresistance within the isolates from a single patient [35].

The main limitations of this study are the absence of phenotypic DST for pyrazinamide and second-line drugs which precluded comparisons with WGS, and the low number of tested isolates.

5. Conclusion

To investigate DR-TB in clinical practice we start with phenotypic DST for first-line drugs and only if resistance is detected, injectable second-line drugs (iSLD) and fluoroquinolones are tested. The same flow is followed for DR-TB investigation with genotypic DST. If rifampicin resistance is detected with Xpert or Genotype MTBDRplus, another genotypic DST for fluoroquinolones and iSLD susceptibility evaluation is required. WGS offers all the information about drug resistance in a single test. In this study, WGS also detected Val170Phe rpoB mutation not covered by commercial genotypic DST, which is the great differential for the diagnostic strategy.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Professor Lee Harrison (University of Pittsburgh) for research support; Margarida Passeri Nascimento (Mycobacteriology Lab at HC FMRP-USP) for technical support; Center for Medical Genomics (CMG) at the Clinics Hospital of Ribeirão Preto (FMRP-USP) for the technical and research support; and Brazilian National Program for Tuberculosis Control (Denise Arakaki-Sanchez) for the support to perform Xpert-MTB/RIF in these isolates.

Funding information

This work was mainly supported by a grant from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) - Processo 15/13333-3, and partially supported by Fogarty International Center HIV Research Training Program grant, National Institutes of Health, to the University of Pittsburgh (D43TW009753) and Fundaçao de Apoio ao Ensino, Pesquisa e Assistencia do HCFMRP-USP (2015-2017).

These data were not presented before at any place or time.

Abbreviation list

- BWA

Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Tool

- DR-TB

drug-resistant tuberculosis

- DST

drug-susceptibility tests

- E

ethambutol

- Fq

fluoroquinolone

- H

isoniazid

- HBC

high burden countries

- iSLD

injectable second-line drugs

- MDR-TB

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

- PAS

para-aminosalicylic acid

- R

rifampicin

- RRDR

rifampicin-resistance-determining region

- SAM

sequence alignment map

- Sm

streptomycin

- TB

tuberculosis

- WGS

whole genome sequencing

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WT

wild-type

- XDR-TB

extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis

- Z

pyrazinamide

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

We, the authors (CSF; EN; JRP; KP; AD; RMW; WASJ and VRB) state there is no conflict of interest for the authorship of this paper.

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [2].World Health Organization. The end TB strategy - global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chaisson RE, Harrington M. How research can help control tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13(5):558–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Niemann S, Köser CU, Gagneux S, et al. Genomic diversity among drug sensitive and multidrug resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with identical DNA fingerprints. PloS One 2009;4(10). e7407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Keshavjee S, Farmer PE. Tuberculosis, drug resistance, and the history of modern medicine. N Engl J Med 2012;367(10):931–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nicolau I, Ling D, Tian L, Lienhardt C, Pai M. Research questions and priorities for tuberculosis: a survey of published systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PloS One 2012;7(7). e42479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lange C, Abubakar I, Alffenaar JW, et al. Management of patients with multidrug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2014;44(1):23–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Domínguez J, Boettger EC, Cirillo D, et al. Clinical implications of molecular drug resistance testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a TBNET/RESIST-TB consensus statement. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016;20(1):24–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Piersimoni C, Olivieri A, Benacchio L, Scarparo C. Current perspectives on drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: the automated non-radiometric systems. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44(1):20–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Barnard M, Albert H, Coetzee G, et al. Rapid molecular screening for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a high-volume public health laboratory in South Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177(7):787–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hoshide M, Qian L, Rodrigues C, et al. Geographical differences associated with single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in nine gene targets among resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52(5):1322–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lin SY, Desmond EP. Molecular diagnosis of tuberculosis and drug resistance. Clin Lab Med 2014;34(2):297–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Walker TM, Kohl TA, Omar SV, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for prediction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility and resistance: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15(10):1193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Witney AA, Gould KA, Arnold A, et al. Clinical application of whole-genome sequencing to inform treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53(5):1473–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pankhurst LJ, Del Ojo Elias C, Votintseva AA, et al. Rapid, comprehensive, and affordable mycobacterial diagnosis with whole-genome sequencing: a prospective study. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4(1):49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat Rev Genet 2010;11(1):31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Papaventsis D, Casali N, Kontsevaya I, et al. Whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for detection of drug resistance: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23(2):61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Feuerriegel S, Köser CU, Niemann S. Phylogenetic polymorphisms in antibiotic resistance genes of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(5):1205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Becton, Dickinson and Company BACTEC™ MGIT™ 960 SIRE Kit for the anti-mycobacterial susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. http://legacy.bd.com/ds/technicalCenter/clsi/clsi-960sire.pdf. Acessed November 3, 2017.

- [20].HAIN LIFESCIENCE. Genotype MTBDRplus ver 2.0. Instructions for use 2012. https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/MTBDRplusV2_0212_304A-02-02.pdf. Acessed November 3, 2017.

- [21].World Health Organization. Molecular line probe assays for rapid screening of patients at risk of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [22].HainLifescience. Genotype MTBDRsl ver 2.0. Instructions for use 2015. https://www.immunodiagnostic.fi/wp-content/uploads/MTBDRsl-V2_kit-insert.pdf. Acessed November 3, 2017.

- [23].World Health Organization. Xpert MTB/RIF implementation manual. Technical and operational ‘how-to’: practical considerations. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Larsen MH, Biermann K, Tandberg S, et al. Genetic manipulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2007;6(1). 10A.2.1–10A.2.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Illumina. Nextera® DNA library prep reference guide. https://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_kits/nextera_dna_kit/documentation.html. Acessed November 3, 2017.

- [26].Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25(14):1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dippenaar A, Parsons SDC, Miller MA, et al. Progenitor strain introduction of Mycobacterium bovis at the wildlife-livestock interface can lead to clonal expansion of the disease in a single ecosystem. Infect Genet Evol 2017;51:235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 2014 sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014;30(15):2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ponstingl H, Ning Z. SMALT - a new mapper for DNA sequencing reads. 2010. F1000 Posters 1. [Google Scholar]

- [30].McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a Map Reduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20(9):1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Winglee K, Manson McGuire A, Maiga M, et al. Whole Genome Sequencing of Mycobacterium africanum strains from Mali provides insights into the mechanisms of geographic restriction. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016;10(1):e0004332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lew JM, Kapopoulou A, Jone LM, Cole ST. TubercuList – 10 years after. Tuberculosis 2011;91(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Coll F, McNerney R, Preston MD, et al. Rapid determination of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance from whole-genome sequences. Genome Med 2015;7(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Stamatakis A. Using RAxML to infer phylogenies. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2015;51(6):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chatterjee A, Nilgiriwala K, Saranath D, et al. Whole genome sequencing of clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Mumbai, India: a potential tool for determining drug-resistance and strain lineage. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2017;107:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Witney AA, Cosgrove CA, Arnold A, et al. Clinical use of whole genome sequencing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Med 2016;14:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ramaswamy S, Musser JM. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber Lung Dis 1998;79(1):3–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Brossier F, Sougakoff W, Aubry A, et al. Molecular detection methods of resistance to antituberculosis drugs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Med Mal Infect 2017;47(5):340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Andre E, Goeminne L, Cabibbe A, et al. Consensus numbering system for the rifampicin resistance-associated rpoB gene mutations in pathogenic mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23(3):167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Andre E, Goeminne L, Colmant A, et al. Novel rapid PCR for the detection of Ile491Phe rpoB mutation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a rifampicin-resistance-conferring mutation undetected by commercial assays. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23(4):267. e5–267.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Unissa AN, Subbian S, Hanna LE, Selvakumar N. Overview on mechanisms of isoniazid action and resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Genet Evol 2016;45:474–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bollela VR,Namburete EI, Feliciano CS, et al. Detection of katG and inhA mutations to guide isoniazid and ethionamide use for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016;20(8):1099–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Morlock GP, Crawford JT, Butler WR, et al. Phenotypic characterization of pncA mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000;44(9):2291–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nusrath Unissa A, Hanna LE. Molecular mechanisms of action, resistance, detection to the first-line anti tuberculosis drugs: rifampicin and pyrazinamide in the post whole genome sequencing era. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2017;105:96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chang KC, Yew WW, Zhang Y. Pyrazinamide susceptibility testing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55(10):4499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].World Health Organization. WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis - 2016 update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gillespie SH. Evolution of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: clinical and molecular perspective. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46(2):267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tudó G, Rey E, Borrell S, et al. Characterization of mutations in streptomycin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in the area of Barcelona. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(11):2341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jagielski T, Ignatowska H, Bakuła Z, et al. Screening for streptomycin resistance-conferring mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from Poland. PLoS One 2014;9(6):e100078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wong SY, Lee JS, Kwak HK, et al. Mutations in gidB confer low-level streptomycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55(6):2515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Scardigli A, Caminero JA. Management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Curr Respir Care Rep 2013;2:208–17. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sun Z, Zhang J, Zhang X, et al. Comparison of gyrA gene mutations between laboratory-selected ofloxacin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and clinical isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008;31(2):115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Namburete EI, Tivane I, Lisboa M, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in Central Mozambique: the role of a rapid genotypic susceptibility testing. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Silva Feliciano C, Rodrigues Plaça J, Peronni K, et al. Evaluation of resistance acquisition during tuberculosis treatment using whole genome sequencing. Braz J Infect Dis 2016;20(3):290–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]