Abstract

Background:

This study investigated mechanism of action of atogepant, a small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonist recently approved for preventive treatment of episodic migraine, by assessing its effect on activation of mechanosensitive C- and Aδ -meningeal nociceptors following cortical spreading depression (CSD).

Methods:

Single-unit recordings of trigeminal ganglion neurons (32 Aδ and 20 C-fibers) innervating the dura was used to document effects of orally administered atogepant (5mg/kg) or vehicle on CSD-induced activation in anesthetized male rats

Results:

Bayesian analysis of time effects found that atogepant did not completely prevent the activation of nociceptors at the tested dose, but it significantly reduced response amplitude and probability of response in both the C- and the Aδ -fibers at different time intervals following CSD induction. For C-fibers, the reduction in responses was significant in the early (first hour), but not delayed phase of activation, whereas in Aδ -fibers, significant reduction in activation was apparent in the delayed (second and third hours) but not early phase of activation.

Conclusions:

These findings identify differences between the actions of atogepant, a small molecule CGRP antagonist (partially inhibiting both Aδ and C-fibers) and those found previously for fremanezumab, a CGRP-targeted antibody (inhibiting Aδ fibers only) and onabotulinumtoxinA (inhibiting C-fibers only)- suggesting that these agents differ in their mechanisms for the preventive treatment of migraine

Keywords: Migraine, Headache, trigeminovascular, gepants, CGRP monoclonal antibodies, pain

Introduction:

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is thought to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of migraine headache, at least in part due to its actions as a neuroeffector and neuromodulator released from the peripheral and central endings of nociceptive sensory neurons in the trigeminal ganglion that innervate the intracranial meninges. Agents that interfere with the action of CGRP have been an important area for drug development and advances in treatment for migraine. Consequently, they are the subject of ongoing intensive investigation into both their clinical effects and their underlying mechanisms. Among such agents are CGRP receptor antagonists, including the peptide CGRP8–37 and the small molecule gepants, as well as monoclonal antibodies that target either CGRP or its receptor.

In agreement with all pivotal clinical studies on the efficacy of the CGRP monoclonal antibodies as well as the gepants1–7, behavioral studies in rodents have found therapeutic effects of CGRP inhibitors in several models of headache, including systemic GTN8–11, dural application of inflammatory mediators12 or potassium chloride13, 14, spontaneous facial hypersensitivity10, 15, traumatic brain injury16, 17, medication overuse headache18, CGRP-induced photophobia19, and umbellulone-induced hyperalgesic priming20, and electrophysiological or fos expression studies found inhibitory effects of these agents in response to GTN or other nitric oxide donors21–23, or direct electrical or chemical stimulation of the dura24, 25, but not CSD24 - where the observed reduction in percentage of activated Aδ did not reach statistical significance during the relatively short (1 hr) post-CSD recording period.

Relevant to the current study, we previously showed that intravenous administration of one of the three humanized monoclonal anti-CGRP antibodies, fremanezumab, selectively inhibits cortical spreading depression (CSD)-induced activation of thinly myelinated Aδ- but not unmyelinated C-fiber subpopulation of meningeal nociceptors26, and high-threshold but not wide-dynamic-range class of neurons in the spinal trigeminal nucleus27. There may be fundamental differences across all agents that neutralize CGRP effects (i.e., fremanezumab, galcanezumab eptinezumab, erenumab, atogepant, rimagepant), raising the possibility that their mechanisms of action in migraine prevention differ, to the extent that their effects on the trigeminovascular pathway may not be the same. Such differences include (a) mode of administration, (b) CGRP ligand antibodies but not CGRP receptor inhibitors’ ability to neutralize the CGRP ligand, (c) CGRP receptor inhibitors but not CGRP ligand antibodies ability to bind the canonical CGRP receptor (CLR/RAMP1) and the AMY1 receptor (CTR/RAMP1) and compete with their corresponding ligands (CGRP and amylin), (d) CGRP receptor inhibitors’ ability to antagonize αCGRP and amylin signaling through their action on the CGRP and AMY1 receptors compared to CGRP ligand antibodies’ ability to antagonize the αCGRP but not the amylin signaling, (e) CGRP receptors inhibitors’ facilitation of CGRP and AMY1 receptor internalization vs. CGRP ligand antibodies’ prevention/reduction of such internalization, (f) size of molecules or (g) receptor pharmacology/selectivity28–33.

Accordingly, the goal of the current study was to investigate the effects of atogepant - a small molecule CGRP receptor antagonist recently approved for migraine prevention- on immediate and delayed evoked activity of mechanosensitive unmyelinated C- and thinly-myelinated Aδ-meningeal nociceptors, and to determine how similar and dissimilar these effects are to the effects identified in the fremanezumab and onabotulinumtoxinA studies. As in other studies using this model (Melo-Carrillo A 2017a/b; Melo-Carrillo A 2020), neuronal activation was evoked by CSD, a cortical event that has been implicated in the initiation of migraine attacks34 and the activation of peripheral and central trigeminovascular neurons35, 36

Materials and Methods

Surgical Preparation

Experiments were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School standing committees on animal care and were in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. A total of 12 female and 86 male Sprague-Dawley rats (225–300 g) were used, including those experiments (approximately 30%) which did not yield data due to failure to obtain a stable single-unit recording from a dural primary afferent neuron. (As explained below, due to technical difficulties, the Results only reports data from the experiments in male rats.) Rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.5 g/kg i.p.), and treated with atropine (0.4 ml i.p.) to reduce intraoral secretions. Core temperature was maintained at 37°C using a feedback-controlled heating pad. An endotracheal tube was implanted, and the rat was mounted in a stereotaxic apparatus. Artificial ventilation with O2 inhalation was initiated through the endotracheal tube, and pO2 was maintained above 98% throughout the experiment. A flexible plastic tube (PE 160) was inserted through the mouth into the stomach for gavage administration of drugs.

A craniotomy was made to expose the left transverse sinus, to allow electrical and mechanical stimulation of dural primary afferent nociceptors. A small burr hole was drilled in the calvarium on the left side, at approximately 2 mm rostral to Bregma and approximately 1.5 mm lateral, to allow insertion of a glass saline-filled micropipette through the intact dura into the cortex, for recording of electrocorticogram activity. A second burr hole was drilled approximately 5 mm caudal to the first one, and approximately 3mm lateral (approximately 5 mm rostral to the transverse sinus), for induction of cortical spreading depression by pinprick (brief manual insertion of a metal microelectrode through the dura into the cortex). All of the exposed dura was kept moist using saline. For neural recording from the left trigeminal ganglion, a craniotomy was made on the right (contralateral) side to allow the microelectrodes to be advanced through the contralateral (right) cortex to reach the left ganglion, using an angled approach. This angled approach was used to avoid damage to the ipsilateral cortex by the microelectrode. The craniotomy for ganglion recording was made to allow electrode insertions into the right cortex covering an area of 1–3 mm caudal to Bregma, and 1.5–3 mm lateral. The dura covering this area of cortex was removed to allow microelectrode insertion. The experimental setup and orientation of electrodes is illustrated in Figure 1A.

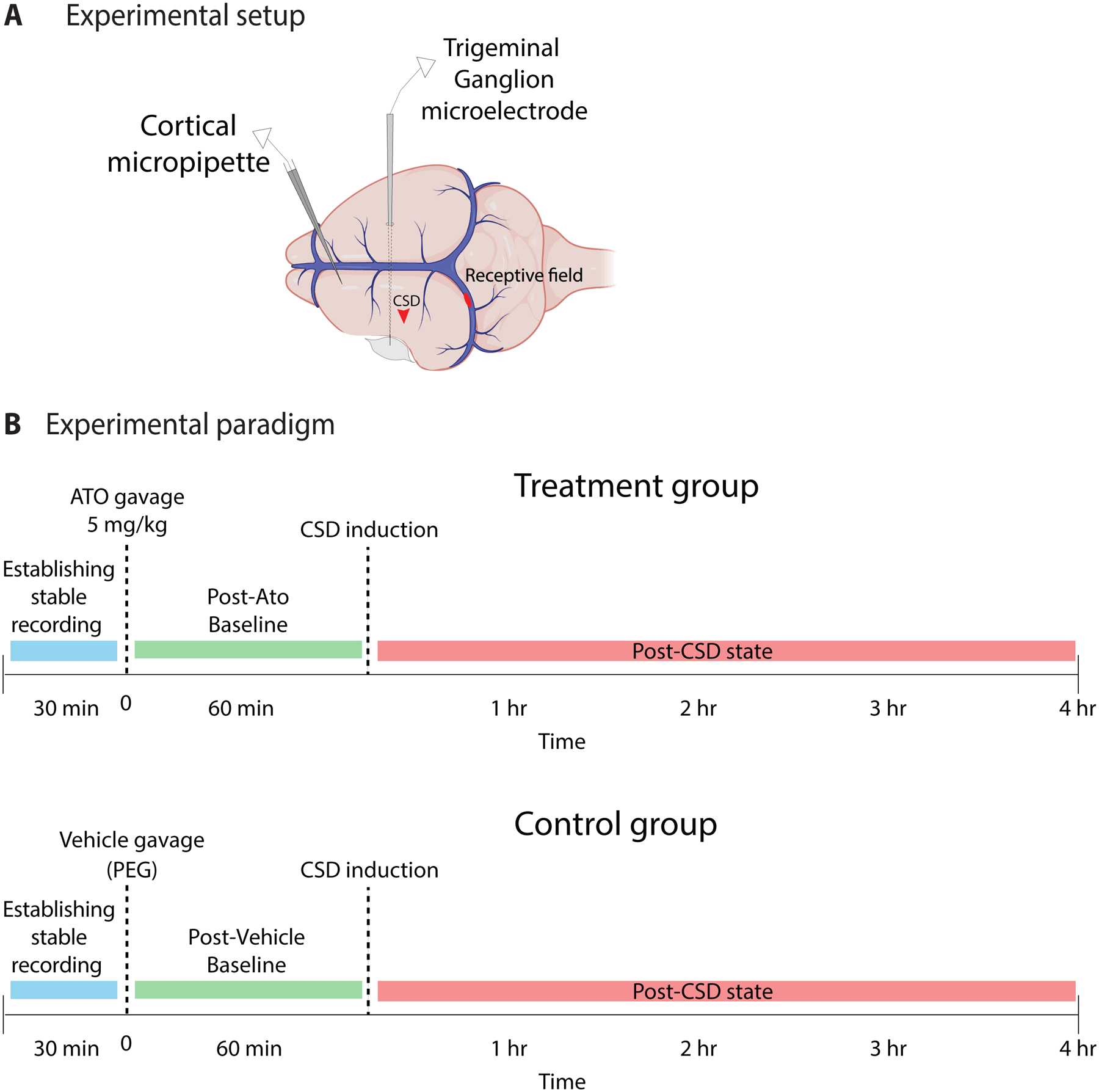

Fig.1.

Experimental setup and paradigm. (A) Cortical micropipette was inserted into frontal cortex for electrocorticogram recording of CSD. Trigeminal ganglion microelectrode was advanced through the contralateral (right) cortex with a medial angle to reach the left trigeminal ganglion, for unit recording of activity of meningeal nociceptors with dural receptive fields. CSD was induced by pinprick in the parietal cortex (red arrowhead). A representative mechanical receptive field is shown on the transverse sinus. (B) Experimental paradigm.

Neural recording

A glass micropipette (1–5 μm tip) filled with 0.9% saline was inserted through the rostral burr hole approximately 1 mm below the cortical surface for electrocorticogram recording. A platinum-coated tungsten microelectrode (impedance 150–250 kΩ) was advanced into the trigeminal ganglion for single-unit recording. To reach the ganglion via a contralateral approach, the electrode was angled medially 21° and was advanced through the contralateral cortex (see above for coordinates). Dural afferent neurons in the ganglion were identified by their constant latency response to single shock stimulation delivered to the dura overlying the ipsilateral transverse sinus with a bipolar stimulating electrode (0.5 ms pulse, 5 mA, 0.75 Hz). The response latency was used to calculate conduction velocity (c.v.), based on a conduction distance to the trigeminal ganglion of 12 mm. Neurons were classified as either C- (c.v.≤1.0 ms) or Aδ-units (c.v. > 1.0 m/s) (Fig. 2A). Spike 2 software (CED, Cambridge, UK) was used for acquisition and waveform discrimination of the spikes, and for offline analysis.

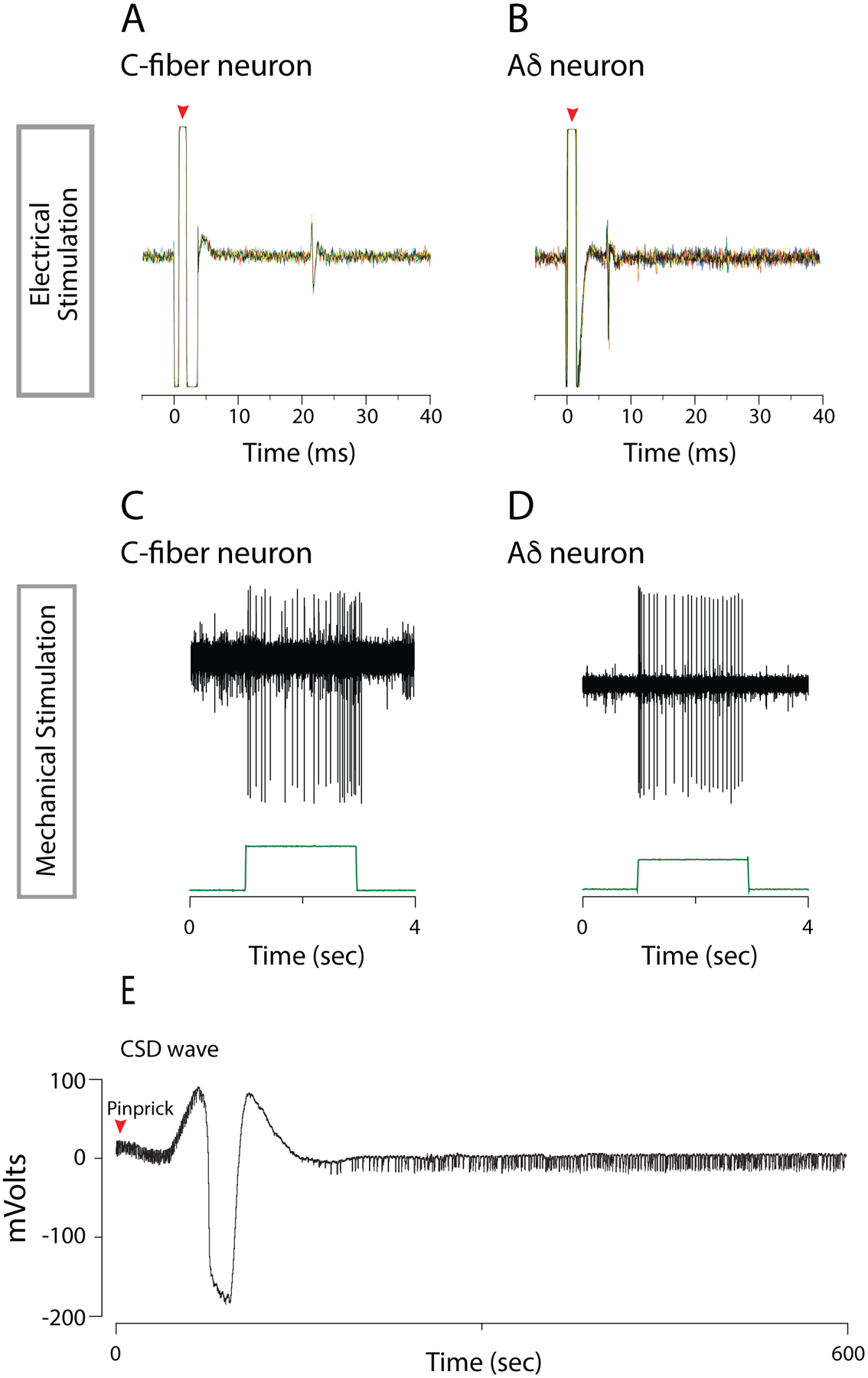

Fig.2.

Electrophysiological characterization of meningeal nociceptors and CSD. A,B. Electrophysiological recordings of action potentials in C-fiber (A) and Aδ-fiber (B) meningeal nociceptors evoked by single shock electrical stimulation applied to the transverse sinus. 5 traces are overlaid to show the constancy of the response latency. Red triangle indicates the shock artefact. C.D. Action potentials evoked in C-fiber (C) and Aδ-fiber (D) meningeal nociceptors by mechanical stimulation of the dural receptive field on the transverse sinus.

E. Electrocorticogram recording of CSD wave (with concurrent silencing of background activity) induced by cortical pinprick.

Mechanical receptive fields of dural afferents were identified by probing the dura with blunt forceps and von Frey hairs, and by indenting with a mechanical stimulator (Fig. 2B). Only neurons for which a mechanical receptive field could be identified were selected for study.

Experimental paradigm

Only one neuron was studied in each animal. Once a dural afferent neuron was identified and characterized as described above, ongoing discharge activity was recorded continuously until the end of the experiment. In order to investigate the effect of atogepant pretreatment on the neural response to CSD, atogepant (5mg/kg in a volume of 2ml/kg) or vehicle [polyethylene glycol (PEG), 2 ml/kg] was infused by gavage into the stomach, and CSD was induced one hour after the infusion. Atogepant has a weaker affinity for CGRP receptors in the rat than in the human, so it is important to use a dose that is sufficient for inhibition of rat CGRP receptors. The gavage dose that we used (5 mg/kg) achieves a maximal plasma concentration (0.8 uM) that is approximately 1000-fold greater than the Ki for atogepant in the rat (values provided by AbbVie), and so should be more than sufficient for supra-maximal inhibition of the rat CGRP receptors. Recording continued for 4 hours after CSD induction (Figure 1B).

Initially, we planned to use an i.v. route for drug administration, as had been done in an earlier study of atogepant in central neurons37. However, for the present study, in initial experiments testing the effect of i.v. infusion of this vehicle in primary afferent meningeal nociceptors, 1 hour prior to CSD induction, it was found that 1) the vehicle itself produced a transient increase in activity or instability in firing in some neurons during the 1-hour pre-CSD baseline period, and 2) partly as a result of this instability in baseline activity, the percentage of neurons that had a clear response to the CSD was relatively low. As a result, in a sample of 9 neurons tested in female rats (6 Aδ and 3 C), none of the neurons had a clear response to CSD following i.v. infusion of vehicle. An additional sample of 15 neurons (8 Aδ, 7 C) was then tested in male rats for their response to CSD following i.v. infusion of vehicle. In the male rats, clear responses to CSD were found in 2 neurons, while in an additional 4 neurons the determination of CSD responses was equivocal because of transient increases in activity during the post-infusion baseline period.

It was then decided to try infusion by gavage instead of i.v. For gavage, the vehicle consisted of PEG alone, without the additional agents that comprised the vehicle for i.v. infusion, and it was thought that this might reduce the amount of activation caused by the vehicle. In addition, gavage has the potential advantage that it avoids the sharp initial peak (large rapid rise followed by large, somewhat slower decline) in the blood level of the infused agent and instead produces a flatter, more even temporal profile in blood level (unpublished observations of pharmacokinetic profiles of atogepant by i.v. vs gavage infusion).

It appeared to us that the use of gavage infusion was successful in alleviating the problem of transient post-infusion increases in firing that we had encountered with i.v. infusion.

Data analysis

The 30-min period prior to CSD induction was used as the baseline for determination of CSD responses. Data analysis examined the proportion of neurons that showed a response to CSD, and the amplitude of the response. Data analysis for each neuron was done by a person who was blinded to the treatment group. A neuron was considered to have a response to CSD if its firing rate increased at least 1 standard deviation above baseline for a period of at least 15 min (calculated in 1-min bins). Response latency (time from CSD to the onset of the response) and duration was also calculated for each neuron.

For investigation of drug effect on response amplitude, two types of statistical analysis were done. 1) Friedman Test. Response amplitude was quantified by calculating the total post-CSD firing that exceeded one standard deviation above the baseline rate, analyzed in 1-min bins. In other words, a quantity equal to the mean plus one standard deviation (calculated in 1-min bins) of the firing during the 30-min baseline period was subtracted from the firing in each 1-min bin of the post-CSD period; those values that were greater than zero were then summed and used in the analysis (i.e. negative values were treated as zero). Statistical comparisons of these values were done in 30-minute intervals over the 4-hr post-CSD period, using the Friedman test with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons. Continuous variables are presented as median [interquartile range: 25th percentile – 75th percentile]. Statistical significance was set at p-value<0.05.]

2) Bayesian Analysis. To examine the differences in treatments (atogepant vs vehicle) in response to time, a Bayesian hierarchical linear model was conducted. This model accommodates the repeated measures (0 to 210 minutes) for each cell. The firing rate was modeled using a Gaussian distribution with identity link. Separate models were conducted for Aδ and C-fibers. For each model, the firing rate was conditioned on baseline firing rates from each cell, treatment group, time, and group × time interaction. Each cell was given its own intercept (i.e., random intercept) and prior distributions for all parameters were based on weakly informative priors with automatic scaling to provide regularization as outlined in the ‘rstanarm’ package. Estimation was conducted using the default settings with four MCMC chains and 2000 iterations each. The posterior distributions were used for inference by extracting the median and 90% credible interval (90%CrI). When a credible interval contrasting treatment excludes 0, the treatments were considered different. All analyses were conducted using RStudio with R 4.0.

Results

Single-unit discharge activity was recorded from 32 Aδ and 20 C-fiber meningeal nociceptors in the trigeminal ganglion that were identified by their response to electrical and mechanical stimulation of the dura overlying the ipsilateral transverse sinus. In all cases, the effect of CSD on neuronal discharge was tested following gavage (intragastric infusion) of either atogepant (n = 21 Aδ and 14 C-fibers) or vehicle (n = 11 Aδ and 6 C-fibers).

Baseline firing rates

Baseline firing rates during the 30-min interval prior to CSD induction were similar for Aδ vs C-fibers (0.54 [0.19–0.81] and 0.60 [0.15–1.06] spikes/sec, respectively (median [IQR]) and for neurons pre-treated with atogepant vs vehicle (0.49 [0.17–1.06] and 0.55 [0.35–0.70] spikes/sec, respectively.

Incidence and latency of CSD responses

For Aδ neurons, a response to CSD was found in 8/11 (73%) neurons treated with vehicle and 8/14 (57%) neurons treated with atogepant (p=.42, Chi-square). For C neurons, a response to CSD was found in 5/6 (83%) neurons treated with vehicle and 5/9 (56%) neurons treated with atogepant (p=.26, Chi-square). In the majority of neurons (21/26, 73%), response latency was less than 30 minutes (13 [2.5–42.5] (median [IQR]).

Response amplitude: Analysis 1, Friedman Test

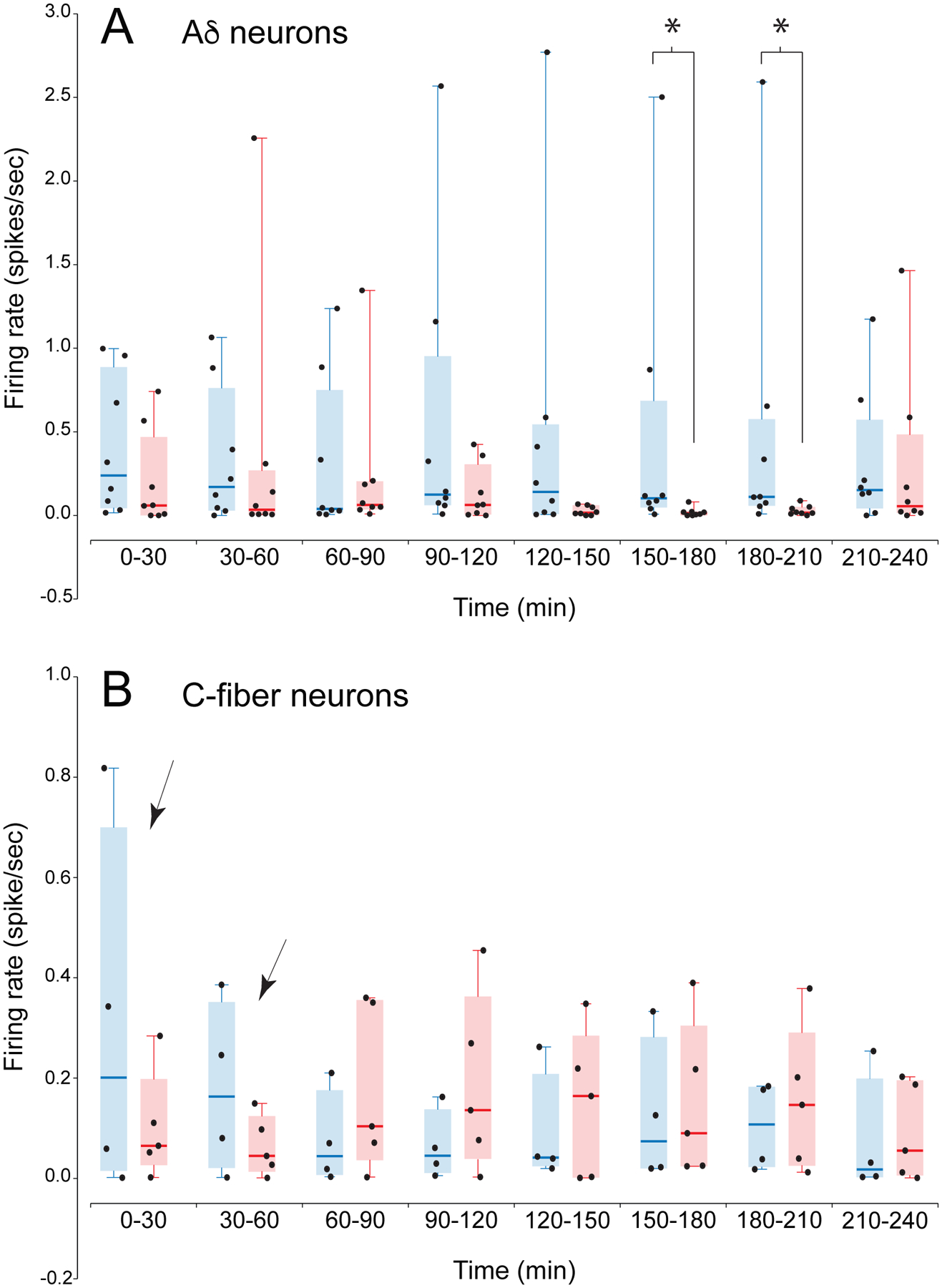

For Aδ neurons that responded to CSD, response amplitude was significantly lower in atogepant- vs vehicle-treated neurons (χ2 (15)= 26.606, p=0.03, Friedman) (Fig. 4A). Differences were significant for the time intervals of 150–180 minutes (p=0.019) and 180–210 minutes (p=0.0428), and there was a trend toward significance for the interval of 120–150 minutes (p=0.058) (Bonferroni post-hoc test). For C neurons, there was no significant difference in response amplitude between the atogepant- and vehicle-treated samples (χ2 (15)= 13.081, p=0.60, Friedman test) (Fig. 4B), but the earlies time interval (marked by arrows in Fig. 4B) showed a high probability of a difference between atogepant and vehicle in the Bayesian analysis.

Fig.4.

CSD response amplitudes of Aδ-neurons (A) and C-fiber neurons (B). Amplitudes are shown as scatterplots of the values for the individual neurons combined with box-and whisker plots (median and inter-quartile range) Only neurons that had a response to CSD are included in the plots and the analysis of response amplitude. Response amplitude was quantified as the activity that was more than 1 standard deviation above the baseline rate. (In other words, the number of spikes that equals 1 standard deviation above the mean, calculated during the baseline period in 1-minute bins, was subtracted from each 1-minute bin post-CSD. Bins with negative values after this subtraction were assigned zero.) Amplitudes of each neuron were averaged in 30-minute intervals, and expressed in spikes/sec. *, p<.05 for atogepant vs vehicle. The Friedman test for atogepant vs vehicle was significant for the Aδ neurons (p=.03, with significant differences at 150–180 and 180–210 minutes in post-hoc comparisons), The Friedman test was not significant for the C-fiber neurons, but two time intervals (indicated by arrows in B) showed a high probability of a difference in the Bayesian analysis in Fig. 5.

Response amplitude: Analysis 2, Bayesian Analysis

Aδ neurons (Fig .5A).

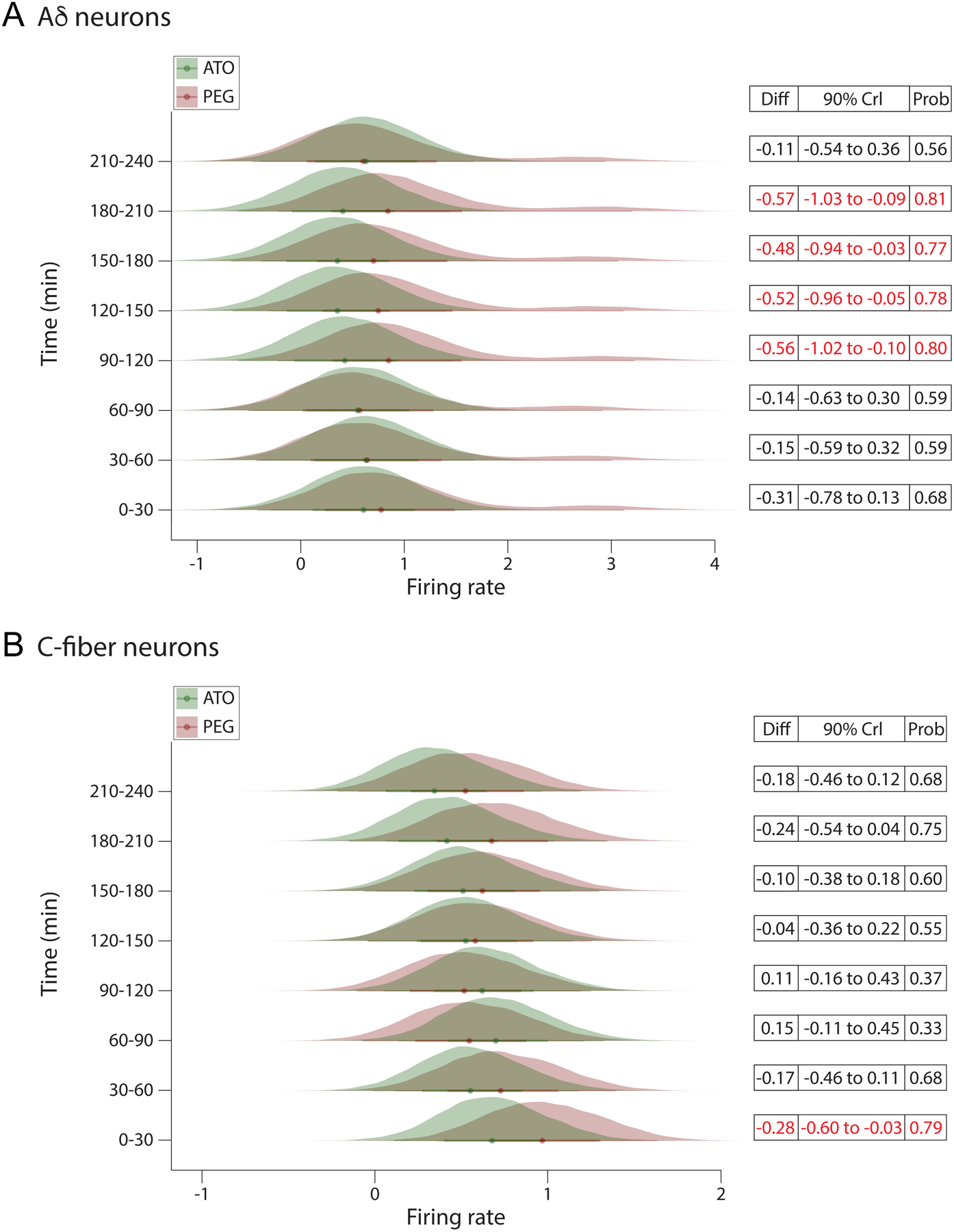

Fig.5.

The posterior probability distributions from the Bayesian hierarchical linear models. A, Aδ-neurons. B, C-fiber neurons. The x-axis reflects the firing rate with the individual time points depicted on the y-axis. The probability of the firing rate for each group is displayed as a filled density. The differences between each treatment group at each time point can be seen by the lack of overlap between the probability distributions and the distance between the median of each distribution, which is depicted with a colored dot at the center of each distribution. The models used to estimate the posterior probability distributions adjusted the treatment effects by the baseline firing rate of each cell. Crl = credible interval. 90% Crl = 90% chance that the mean difference is between the 2 depicted numbers. Differences are considered significant only when the credible interval does not include 0.

From 0 to 60 minutes, there were little differences between the firing rates of the two treatments. For example, at 60 minutes, the atogepant- treated neurons exhibited a slightly decreased firing rate than vehicle- treated cells, mean difference: −0.15 (90%CrI: −0.63 to 0.30). Beginning at 90 minutes, the atogepant treated cells exhibited a sizable reduction in firing rate increasing the difference between treatments, difference: −0.57 (90%CrI: −1.0 to −0.1). At that time there was a probability of 81% that cells in the atogepant treatment had a lower firing rate than the PEG group. This mean difference in firing rate remained at 120 minutes, −0.53 (90%CrI: −1.0 to −0.05), 150 minutes, −0.48 (90%CrI: −0.95 to −0.03), and 180 minutes, −0.57 (90%CrI: −1.0 to −0.1), with a probability of differences ranging between 77–81%. Between 210 and 240 minutes, the mean difference between treatments was similar to baseline, −0.11 (90%CrI: −0.54 to 0.37).

C neurons (Fig. 5B).

Between 0 and 30 min, the treatment groups exhibited a modest mean difference, −0.29 (90%CrI: −0.60 to −0.04). At that time there was a probability of 79% that cells in the atogepant treatment had a lower firing rate than in PEG group. This difference diminished gradually, becoming near-zero at 120 minutes, −0.05 (90%CrI: −0.36 to 0.23). Although the atogepant group continued to exhibit a reduction in firing rate over time, after 120 minutes the difference between the 2 treatment groups were accompanied by increased within-cell variability, reducing the precision of the treatment effects. For example, at 180 minutes the group difference was, −0.25 (90%CrI: −0.54 to 0.05), which corresponds to 75% chance that the groups differed.

Discussion:

This is the first study to test the effects of an orally administered small molecule CGRP antagonist (gepant) on meningeal nociceptors’ responsivity to CSD in rats. Pre-treatment with atogepant produced delayed and relatively prolonged (90–210 min after occurrence of CSD) inhibition of neuronal firing in the thinly-myelinated Aδ nociceptors and immediate but relatively brief (0–30 min after occurrence of CSD) inhibition of firing in the unmyelinated C-nociceptors. This pattern of inhibition differs from that found for a CGRP-neutralizing antibody, which exerted an inhibitory effect only on A-delta but not on C-nociceptors26. One possible factor that could contribute to such a difference is the potency of atogepan at both the canonical CGRP receptor and the AMY1 receptor29, 31–33, 38, 39.

Given CSD’s tendency to activate C-nociceptors earlier than Aδ nociceptors35, 40 and C-nociceptors presumed ability to release CGRP upon their activation by CSD26, 41, the findings of the current study raise the possibility that the more robust attenuation of firing in the Aδ nociceptors (compared to the atogepant effects on the C-nociceptors) may be achieved primarily through a direct blockade of CGRP receptors by the atogepant and secondarily through a reduction in CGRP release from the C-nociceptors due to atogepant’s ability to antagonize signaling at the AMY1 receptor33, 42. This speculation, however, depends on two yet unknown/unproven assumptions – that unmyelinated C-meningeal nociceptors express AMY1 receptors in the dura, and that amylin signaling plays a role in the activation of the nociceptors by CSD.

Although parenterally administered drugs reach the targeted plasma concentration earlier than orally administered drugs and, in some cases, require a lower dose, oral administration is more commonly used as it is easier to administer, inexpensive, non-invasive, preferred by patients, and can more readily be designed for slow release. Small molecule receptor inhibitors, unlike the CGRP antibodies, are administered orally rather than parenterally. Therefore, testing the effects on the meningeal nociceptors using gavage as the route of administration, rather than the parenteral, mimics the clinical conditions more closely. Given that the impact on the nociceptors was achieved using oral administration of atogepant, it is reasonable to consider the possibility that differences between atogepant and CGRP antibodies effects on CSD-induced activation of meningeal nociceptors may be explained by differences in mechanism of action as well as mode of administration.

In a recent study, we showed that pre-treatment with one of the three CGRP ligand antibodies (fremanezumab) prevents CSD-induced activation of a high percentage of Aδ-meningeal nociceptors but not the activation of the C-meningeal nociceptors by CSD26. In comparison, in the current study we show that oral administration of a small molecule receptor antagonist (atogepant) attenuates part of the CSD-induced response in the Aδ-meningeal nociceptors rather than preventing their activation altogether and that it also attenuates part of the CSD-induced response in the C-meningeal nociceptors, rather than having no effect on their activation by CSD. Taking into consideration the presence of CLR/RAMP1 receptors at nerve endings and nodes of Ranvier of dural Aδ-but not C-nociceptors, and the presence of CGRP in the dural C- but not Aδ-nociceptors41 43, we proposed then that the CGRP ligand antibodies prevented the activation of the dural Aδ- but not C-nociceptors because the activation of the dural Aδ-nociceptors could be triggered (at least partially) by CGRP binding to the CLR/RAMP1 receptors whereas the activation of dural C-nociceptors may be triggered through CGRP-independent mechanisms26. Along this line, we anticipated that a small molecule CGRP receptor antagonist such as atogepant would have similar effects and inhibit only those dural nociceptors whose activation depends partially or fully on CGRP. However, the novel finding that atogepant produced early and relatively brief inhibition of CSD-induced firing in the dural C-nociceptors suggests that atogepant may bind to a receptor on the C-nociceptor that is activated by a molecule other than CGRP. One possibility is that there are CTR/RAMP1 (AMY1) receptors on dural C-nociceptors and that atogepant competes successfully with amylin on binding them. Presence of AMY1 mRNA in small and medium somas in the trigeminal ganglion further supports this possibility29, 44, although the anatomical localization of the receptor in the dura has not yet been studied.

Regarding the resumption of firing an hour after the CSD occurrence, one could speculate that the immediate CSD-induced activation in the dural C-nociceptors may be mediated mainly by AMY1 receptor31, 33, 38, 39 whereas the delayed activation may depend on later recruitment of the CTR/RAMP3 (AMY3) receptors on the satellite ganglia cells surrounding the small diameter neurons in the ganglion. One additional factor that could contribute to the differences between a small molecule and the antibody is the size of the agents, which might result in different penetration into the dura and other layers of the meninges. Nevertheless, the implications of these potential mechanistic differences can only be identified in clinical and real-world studies comparing the efficacy of these two drugs.

We also anticipated that the prevention of CSD-induced activation of the dural Aδ-nociceptors by the small molecule receptor inhibitor would be comparable to their prevention by the CGRP ligand antibody. However, the finding that atogepant was able to reduce the CSD-induced firing frequency of the Aδ-nociceptors with a 90-minute delay, rather than completely preventing their activation in the first place, suggests that CSD-induced activation of the Aδ-nociceptors may not be dependent solely on CGRP binding to the CLR/RAMP1 receptors. Given the delayed and partial blockade of neuronal firing, it seems unlikely that atogepant availability in the dura and trigeminal ganglion was insufficient to block all CLR/RAMP1 receptors. Rather, it is tempting to suggest that delayed internalization of the CLR/RAMP1 receptor due to the delayed release of CGRP from the C-nociceptors may have lessened the CGRP impact. In the absence of data on the timing of receptors internalization following their activation in the dura, however, this proposal must await further evidence.

Under normal conditions, most nociceptive inputs that reach dorsal horn neurons from the periphery are too weak to evoke action potentials in the post-synaptic neurons45. But when intensity or duration of activity increases, summation of slow synaptic potentials increases depolarization to the extent that it grants nociceptive signals the ability to evoke action potentials that over time lead to facilitation, potentiation or sensitization of nociceptive dorsal horn neurons46–50. In contrast, when the nociceptive input decreases, the remaining nociceptive signals can no longer potentiate or sensitize the dorsal horn neurons, and if given enough time, can lead to reduced excitation and loss of sensitization46–50. Following these well-established principles, we propose that the reduction in overall firing frequency of 2 classes of meningeal nociceptors, at different time periods after induction of CSD, may be sufficient to reduce synaptic strength to the extent that the remaining nociceptive signals are too weak to evoke action potentials in the post-synaptic trigeminovascular neurons.

Caveat: The absence of females is a limitation of this study. Given the high prevalence of migraine in women, repeating this study in female rats is warranted. As noted in the Methods, experiments were initially carried out in females, but those experiments did not yield useful results because of technical difficulties with the method of drug administration and its effect on neuronal responses. After switching to males, and then switching to gavage administration, the experiments were successful, but we did not at that point return to obtaining a sample with gavage in females as we did not want to delay further the reporting of the findings in males.

In conclusion, the findings in the current study suggest that atogepant can partially prevent activation of both the Aδ -fiber and C-fiber meningeal nociceptors (by CSD), which differs from results found in similar models for fremanezumab, a CGRP-targeted mAb, and onabotulinumtoxinA.

Fig.3.

Plots of firing rate of Aδ- and C-fiber meningeal nociceptors that had been pre-treated with atogepant (ATO) or vehicle (PEG) one hour prior to induction of CSD (induced by pinprick at time = 0). A. Examples of neurons that were activated by the CSD. B. Examples of neurons that were not activated by the CSD. The Ad neuron pre-treated with atogepant in B displayed a brief period of firing immediately following the CSD induction that was too brief to meet our criterion for a responsive neuron (< 15 minutes). The horizontal red line in each plot marks the firing level one standard deviation above the baseline rate. Note that the Aδ-neurons pre-treated with atogepant in A had a pronounced activation that declined markedly around 100 minutes post-CSD, whereas the Aδ neuron pre-treated with vehicle in A had a response that seemed to still be continuing at the end of the 4-hr post-CSD recording period.

Highlights.

Orally administered atogepant produces delayed but prolonged inhibition of firing in Aδ nociceptors and immediate but brief inhibition of firing in C-nociceptors.

This pattern of inhibition differs from that found for a monoclonal antibody against CGRP (fremanezumab), which might be a result of the previously reported dual action of the gepants at both the CGRP and the AMY(1) receptor.

Acknowledgement:

This study was supported by a grant from Allergan, an AbbVie company, and NIH grants R37-NS079678, RO1 NS069847, RO1 NS094198 (RB). RB received research funding from Allergan and AbbVie. He is also a consultant to these companies. AA and MFB are employees of Allergan, an AbbVie Company. Other authors have no competing interests.

References:

- 1.Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of Ubrogepant vs Placebo on Pain and the Most Bothersome Associated Symptom in the Acute Treatment of Migraine: The ACHIEVE II Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019; 322: 1887–1898. 2019/11/20. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 737–745. 2019/07/18. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31606-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered atogepant for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults: a double-blind, randomised phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2020; 19: 727–737. 2020/08/22. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, et al. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: Results of the EVOLVE-2 Phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1442–1454. 2018/06/01. DOI: 10.1177/0333102418779543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silberstein S, Diamond M, Hindiyeh NA, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of chronic migraine: efficacy and safety through 24 weeks of treatment in the phase 3 PROMISE-2 (Prevention of migraine via intravenous ALD403 safety and efficacy-2) study. J Headache Pain 2020; 21: 120. 2020/10/08. DOI: 10.1186/s10194-020-01186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the Preventive Treatment of Chronic Migraine. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 2113–2122. 2017/11/25. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, et al. ARISE: A Phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1026–1037. 2018/02/24. DOI: 10.1177/0333102418759786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y, Shi Z, Kashyap Y, et al. Protein kinase C delta as a neuronal mechanism for headache in a chronic intermittent nitroglycerin model of migraine in mice. Pain 2021. 2021/06/11. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen SL, Ernstsen C, Olesen J, et al. No central action of CGRP antagonising drugs in the GTN mouse model of migraine. Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 924–934. 2020/04/01. DOI: 10.1177/0333102420914913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen SL, Petersen S, Kristensen DM, et al. Targeting CGRP via receptor antagonism and antibody neutralisation in two distinct rodent models of migraine-like pain. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 1827–1837. 2019/07/11. DOI: 10.1177/0333102419861726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernstsen C, Christensen SL, Olesen J, et al. No additive effect of combining sumatriptan and olcegepant in the GTN mouse model of migraine. Cephalalgia 2021; 41: 329–339. 2020/10/17. DOI: 10.1177/0333102420963857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Felice M, Eyde N, Dodick D, et al. Capturing the aversive state of cephalic pain preclinically. Ann Neurol 2013; 74: 257–265. 2013/05/21. DOI: 10.1002/ana.23922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filiz A, Tepe N, Eftekhari S, et al. CGRP receptor antagonist MK-8825 attenuates cortical spreading depression induced pain behavior. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 354–365. 2017/10/04. DOI: 10.1177/0333102417735845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang C, Unekawa M, Kitagawa S, et al. Cortical spreading depolarisation-induced facial hyperalgesia, photophobia and hypomotility are ameliorated by sumatriptan and olcegepant. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 11408. 2020/07/12. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-67948-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munro G, Petersen S, Jansen-Olesen I, et al. A unique inbred rat strain with sustained cephalic hypersensitivity as a model of chronic migraine-like pain. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 1836. 2018/02/01. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-19901-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bree D and Levy D. Development of CGRP-dependent pain and headache related behaviours in a rat model of concussion: Implications for mechanisms of post-traumatic headache. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 246–258. 2016/12/03. DOI: 10.1177/0333102416681571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navratilova E, Rau J, Oyarzo J, et al. CGRP-dependent and independent mechanisms of acute and persistent post-traumatic headache following mild traumatic brain injury in mice. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 1762–1775. DOI: 10.1177/0333102419877662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopruszinski CM, Xie JY, Eyde NM, et al. Prevention of stress- or nitric oxide donor-induced medication overuse headache by a calcitonin gene-related peptide antibody in rodents. Cephalalgia 2017; 37: 560–570. 2016/05/22. DOI: 10.1177/0333102416650702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason BN, Wattiez AS, Balcziak LK, et al. Vascular actions of peripheral CGRP in migraine-like photophobia in mice. Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 1585–1604. 2020/08/20. DOI: 10.1177/0333102420949173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopruszinski CM, Navratilova E, Swiokla J, et al. A novel, injury-free rodent model of vulnerability for assessment of acute and preventive therapies reveals temporal contributions of CGRP-receptor activation in migraine-like pain. Cephalalgia 2021; 41: 305–317. 2020/09/29. DOI: 10.1177/0333102420959794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran R, Bhatt DK, Ploug KB, et al. Nitric oxide synthase, calcitonin gene-related peptide and NK-1 receptor mechanisms are involved in GTN-induced neuronal activation. Cephalalgia 2014; 34: 136–147. 2013/09/04. DOI: 10.1177/0333102413502735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feistel S, Albrecht S and Messlinger K. The calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist MK-8825 decreases spinal trigeminal activity during nitroglycerin infusion. J Headache Pain 2013; 14: 93. 2013/11/22. DOI: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koulchitsky S, Fischer MJ and Messlinger K. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor inhibition reduces neuronal activity induced by prolonged increase in nitric oxide in the rat spinal trigeminal nucleus. Cephalalgia 2009; 29: 408–417. 2008/12/06. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao J and Levy D. The CGRP receptor antagonist BIBN4096 inhibits prolonged meningeal afferent activation evoked by brief local K(+) stimulation but not cortical spreading depression-induced afferent sensitization. Pain Rep 2018; 3: e632. 2018/02/13. DOI: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storer RJ, Akerman S and Goadsby PJ. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) modulates nociceptive trigeminovascular transmission in the cat. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 142: 1171–1181. 2004/07/09. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melo-Carrillo A, Strassman AM, Nir RR, et al. Fremanezumab-A Humanized Monoclonal Anti-CGRP Antibody-Inhibits Thinly Myelinated (Adelta) But Not Unmyelinated (C) Meningeal Nociceptors. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 10587–10596. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melo-Carrillo A, Noseda R, Nir RR, et al. Selective Inhibition of Trigeminovascular Neurons by Fremanezumab: A Humanized Monoclonal Anti-CGRP Antibody. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 7149–7163. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0576-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gingell JJ, Rees TA, Hendrikse ER, et al. Distinct Patterns of Internalization of Different Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Receptors. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2020; 3: 296–304. 2020/04/17. DOI: 10.1021/acsptsci.9b00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker CS, Eftekhari S, Bower RL, et al. A second trigeminal CGRP receptor: function and expression of the AMY1 receptor. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015; 2: 595–608. 2015/07/01. DOI: 10.1002/acn3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manoukian R, Sun H, Miller S, et al. Effects of monoclonal antagonist antibodies on calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor function and trafficking. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 44. 2019/05/02. DOI: 10.1186/s10194-019-0992-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hay DL, Christopoulos G, Christopoulos A, et al. Determinants of 1-piperidinecarboxamide, N-[2-[[5-amino-l-[[4-(4-pyridinyl)-l-piperazinyl]carbonyl]pentyl]amino]-1-[(3,5-d ibromo-4-hydroxyphenyl)methyl]-2-oxoethyl]-4-(1,4-dihydro-2-oxo-3(2H)-quinazoliny l) (BIBN4096BS) affinity for calcitonin gene-related peptide and amylin receptors--the role of receptor activity modifying protein 1. Mol Pharmacol 2006; 70: 1984–1991. 2006/09/09. DOI: 10.1124/mol.106.027953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker CS, Raddant AC, Woolley MJ, et al. CGRP receptor antagonist activity of olcegepant depends on the signalling pathway measured. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 437–451. 2017/02/07. DOI: 10.1177/0333102417691762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhakta M, Vuong T, Taura T, et al. Migraine therapeutics differentially modulate the CGRP pathway. Cephalalgia 2021; 41: 499–514. 2021/02/26. DOI: 10.1177/0333102420983282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolay H and Moskowitz MA. The emerging importance of cortical spreading depression in migraine headache. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2005; 161: 655–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Levy D, Noseda R, et al. Activation of meningeal nociceptors by cortical spreading depression: implications for migraine with aura. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 8807–8814. 2010/07/02. DOI: 30/26/8807 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0511-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Levy D, Kainz V, et al. Activation of central trigeminovascular neurons by cortical spreading depression. Ann Neurol 2011; 69: 855–865. 2011/03/19. DOI: 10.1002/ana.22329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melo-Carrillo A, Strassman AM, Schain AJ, et al. Combined onabotulinumtoxinA/atogepant treatment blocks activation/sensitization of high-threshold and wide-dynamic range neurons. Cephalalgia 2021; 41: 17–32. 2020/11/18. DOI: 10.1177/0333102420970507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan KS, Siow A, Hay DL, et al. Antagonism of CGRP Signaling by Rimegepant at Two Receptors. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11: 1240. 2020/09/26. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore E, Fraley ME, Bell IM, et al. Characterization of Ubrogepant: A Potent and Selective Antagonist of the Human Calcitonin GeneRelated Peptide Receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2020. 2020/01/30. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.119.261065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melo-Carrillo A, Strassman AM, Schain A, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA affects cortical recovery period but not occurrence or propagation of cortical spreading depression in rats with compromised blood brain barrier. Pain 2021. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eftekhari S, Warfvinge K, Blixt FW, et al. Differentiation of nerve fibers storing CGRP and CGRP receptors in the peripheral trigeminovascular system. J Pain 2013; 14: 1289–1303. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay DL, Garelja ML, Poyner DR, et al. Update on the pharmacology of calcitonin/CGRP family of peptides: IUPHAR Review 25. Br J Pharmacol 2018; 175: 3–17. DOI: 10.1111/bph.14075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edvinsson JCA, Warfvinge K, Krause DN, et al. C-fibers may modulate adjacent Adelta-fibers through axon-axon CGRP signaling at nodes of Ranvier in the trigeminal system. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 105. DOI: 10.1186/s10194-019-1055-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edvinsson L, Grell AS and Warfvinge K. Expression of the CGRP Family of Neuropeptides and their Receptors in the Trigeminal Ganglion. J Mol Neurosci 2020; 70: 930–944. 2020/02/23. DOI: 10.1007/s12031-020-01493-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woolf CJ and King AE. Subthreshold components of the cutaneous mechanoreceptive fields of dorsal horn neurons in the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 1989; 62: 907–916. 1989/10/01. DOI: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson SW, Woolf CJ and Sivilotti LG. Small-caliber afferent inputs produce a heterosynaptic facilitation of the synaptic responses evoked by primary afferent A-fibers in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro. J Neurophysiol 1993; 69: 2116–2128. 1993/06/01. DOI: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sivilotti LG, Thompson SW and Woolf CJ. Rate of rise of the cumulative depolarization evoked by repetitive stimulation of small-caliber afferents is a predictor of action potential windup in rat spinal neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 1993; 69: 1621–1631. 1993/05/01. DOI: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ji RR and Woolf CJ. Neuronal plasticity and signal transduction in nociceptive neurons: implications for the initiation and maintenance of pathological pain. Neurobiology of disease 2001; 8: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, et al. Central sensitization and LTP: do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci 2003; 26: 696–705. 2003/11/20. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mendell LM. Modifiability of spinal synapses. Physiological reviews 1984; 64: 260–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]