Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Mitochondrial dysfunction is observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the relationship between functional mitochondrial deficits and AD pathologies is not well established in human subjects.

METHODS:

Post-mortem human brain tissue from 11 non-demented (ND) and 12 AD subjects was used to examine mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) function. Data were analyzed by neuropathology diagnosis and Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype. Relationships between AD pathology and mitochondrial function were determined.

RESULTS:

AD subjects had reductions in brain cytochrome oxidase (COX) function and complex II Vmax. APOE ε4 carriers had COX, complex II and III deficits. AD subjects had reduced expression of Complex I-III ETC proteins, no changes were observed in APOE ε4 carriers. No correlation between p-Tau Thr 181 and mitochondrial outcomes was observed, although brains from non-demented subjects demonstrated positive correlations between Aβ concentration and COX Vmax.

DISCUSSION:

These data support a dysregulated relationship between brain mitochondrial function and Aβ pathology in AD.

Keywords: mitochondria, Aβ, cytochrome oxidase, brain, Alzheimer’s disease

INTRODUCTION

Bioenergetic dysfunction is well documented across Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patient tissues and AD models. In vitro and in vivo studies show disruption of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number, reduced flux through the electron transport chain (ETC), increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial calcium, altered mitophagy and mitochondrial mass, and changes to mitochondrial morphology 1, 2. The most robust risk factors for AD, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene and advancing age, influence mitochondrial and bioenergetic function 3–8. The inheritance of specific mtDNA haplotypes associates with AD risk 9, 10. These mtDNA haplotypes may further influence the AD risk confered by APOE isoforms 11, 12. These data suggest that mtDNA inheritance and mitochondrial function play a significant role in AD progression and pathology.

The classic AD pathologies interact with mitochondria. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) and amyloid beta (Aβ) localize to mitochondria13, 14. Gamma secretase is found within mitochondria where it functions to modulate ETC assembly 15–17. Mitochondrial-localized APP and γ-secretase lead to generation of Aβ within mitochondria 14, 18–20. Numerous studies highlight the negative effects of Aβ on mitochondrial function, and mitochondrial dysfunction is observed in APP and APP/PS1-based transgenic mouse models 2, 14, 19, 21, 22. Mitochondrial function also influences APP, Aβ, and tau biology. Altering mitochondrial function can increase or decrease Aβ production and tau phosphorylation 23–26. A fuller understanding of these relationships could benefit the AD field.

A recent study showed that postmortem tissues could be used to support studies of mitochondrial respiration 27, 28. Prior AD studies have largely examined end-point mitochondrial measures such as protein expression, mtDNA copy number, and mitochondrial morphology 1, 29–32. Here we used the newly described assay to asses mitochondrial flux in non-demented and AD postmortem brain. We compared this flux assay with standard Vmax assays while also correlating mitochondrial findings with AD pathologies.

METHODS

Brain Samples.

Human brain samples were obtained from the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (KUADRC) Brain Bank. Brain donors were members of the KUADRC Clinical Cohort, who consented to brain donation upon death and approval from an ethical standards committee to conduct this study was received. Banked tissue is de-identified by the KUADRC Neuropathology Core to eliminate identifying information. We examine the BA10 Broadmann area (frontopolar prefrontal cortex/frontal cortical pole). AD was diagnosed upon neuropathological examination as outlined in the NACC Neuropathology Coding Guidebook33.

APOE Genotyping.

We used a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) allelic discrimination assay to determine APOE genotypes. This involved adding 5 ul of blood to a Taqman Sample-to-SNP kit (ThermoFisher). Taqman probes to the two APOE-defining SNPs, rs429358 (C_3084793_20) and rs7412 (C_904973_10) (ThermoFisher), were used to identify APOE ε2, ε3, and ε4 alleles.

Brain homogenates.

Approximately 10 mg of tissue was thawed on ice and minced with pre-chilled scissors. Samples were then homogenized using 500 µL ice-cold MAS buffer (220 mM Mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.2% fatty acid free BSA) with twenty strokes of a glass-Teflon Dounce homogenizer. Homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 × g, 4°C. The supernatant was collected and used for further analysis.

Seahorse Bioanalyzer Analysis.

Homogenates were loaded into the Seahorse XF96 microplate (from the Seahorse XF96 flux pack) in 20 μl of MAS buffer at a concentration of 30 µg per well. Plates were centrifuged 5 min at 2000 × g, 4°C, using a plate carrier and no centrifuge brake. 160 μl of 1X MAS with 10 μg/ml cytochrome c (final concentration) and 10 μg/ml alamethicin A (final concentration) was added to each well. Cartridge injections of drugs were as follows; A. 1 mM NADH or 5 mM succinate and 2 µM rotenone, B. 4 µM Antimycin A. C. 0.5 mM TMPD and 1 mM ascorbic acid, D. 50 mM Sodium Azide. Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured following a 1-minute mix after addition of injections and measured over 2 minutes three times. Adapted from 27, 28.

Vmax Enzyme Assays.

We added aliquots of the homogenates to 96 well plates and spectrophotometrically determined CI, CII, CIII, CIV (COX), and CS Vmax activities 34–38. For CI we followed the reduction of CoQ to ubiquinol at an absorbance of 340 nM. CI was measured in the presence of 25 mM PBS with 400 µM MgCl2, 150 µM NADH, 1 µM KCN, 60 µM Coenzyme Q1, and 0.25% fatty acid free BSA. Readings for Complex I were completed in the presence or absence of rotenone. For CII the rate of DCPIP reduction to DCPIPH2 was followed at 600 nM in the presence of 40 μM DCPIP, 1 mM KCN, 10 μM rotenone, 50 μM co-enzyme Q2, and 20 mM succinate. For CIII the reduction of cytochrome c at 550 nm in the presence of sodium azide was measured. The CIII assay contained 250 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 20 mM NaN3, 0.25 mM decylubiquinol, and 0.25 mM cytochrome c. For the COX Vmax, we followed the conversion of reduced cytochrome c to oxidized cytochrome c at an absorbance of 550 nm and calculated the pseudo-first order rate constant (msec−1). For the CS Vmax, we followed the formation of 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate (nmol/min) from the conversion of oxaloacetate and acetyl coA to citrate at the absorbance of 462 nm. All Vmax rates were normalized to protein content.

Western Blotting.

50 µg of homogenate protein was resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel (4–15% Criterion gel from BioRad Laboratories). Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in 1X PBS/0.1% Tween. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C with mixing, following which membranes were washed 3X with 1X PBS/0.1% Tween. Secondary antibody (BioRad) was added at a dilution of 1:4,000 in 5% milk/1X PBS and 0.1% Tween for 1 hour at room temperature, with mixing. Membranes were washed 3X with 1X PBS/0.1% Tween and bands were visualized with HRP substrate (WestFemto, ThermoFisher) and a Chemidoc imaging station (BioRad). Densitometry was completed using ImageLab (BioRad). Primary antibodies are listed in Table 1. Total protein images were obtained using AmidoBlack Stain (Sigma).

Table 1.

Antibodies

| Protein Name | Company | Catalog No. | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Ox Phos (ATP5A, SDHB, UQCRC2, NDUFB8) | Abcam | ab110411 | 1:1000 |

| COX4I1 | Cell Signaling | 4850 | 1:1000 |

| CS | Cell Signaling | 14309 | 1:1000 |

ELISAs.

Aβ and tau levels were determined using ELISA assays from ThermoFisher/Invitrogen using the manufacturer’s protocols. All values were normalized to protein content (BCA Assay). For aggreged Aβ measures, tissue was extracted using extraction buffer composed of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 150 mM NaCl with protease inhibitor mix (ThermoFisher). Tissue was added to 10 times volume of extraction buffer, homogenized and sonicated. Samples were then centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was placed in a new tube and diluted for ELISA analysis. The resulting fraction contained TBS-soluble aggregates of Aβ. For Tau, Aβ40 and Aβ42 ELISA analysis, brain tissue was homogenized in 5 M guanidine-HCl diluted in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 with protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher). Tissue was added to 8 volumes of cold 5 M guanidine-HCl in 50 mM Tris and homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. Samples were then mixed on an orbital shaker at room temperature for three hours. The samples were diluted ten-fold with cold PBS with protease inhibitors and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and diluted for ELISA analysis.

Statistics.

Statistical tests and graphs were completed using GraphPad Software. Students T Test, ANOVA,or Pearson correlation test were used. A p value of less than 0.05 is reported as significant. Graphs show mean with standard error. Supplementary materials report all means and 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS

Frontal cortical pole samples (BA10) were obtained from 11 non-demented (ND) and 12 AD subjects. Demographics for the groups are provided in Table 2 with detailed demographics and neuropathology findings listed in Table S1. The postmortem interval (PMI), which represents the time from death to freezing of brain tissue, was shorter in the AD brains although the duration of frozen storage was equivalent between groups. As expected, the AD group had an over-representation of APOE ε4 carriers, with 9/12 APOE ε4 carriers in the AD group and 2/11 APOE ε4 carriers in the ND group. We examined data based on diagnosis of AD via neuropathology, neuropathology scores/staging, and APOE carrier status. When subjects were separated by APOE carrier status this included both ND and AD subjects as we were not powered to separate by both diagnosis and APOE carrier status.

Table 2.

Demographics

| Group | Age years (SD) | Sex (M/F) | PMI hours (SD) | Frozen years (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND | 81.2 (8.7) | 5/6 | 21.2 (16.3) | 5.7 (1.9) |

| AD | 76.3 (8.8) | 9/3 | 7.9 (5.3) | 5.3 (0.96) |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 79.8 (7.7) | 8/3 | 9.2 (6.4) | 5.8 (1.3) |

| APOE ε4 non-carrier | 77.6 (10.1) | 6/6 | 18.9 (16.6) | 5.3 (1.9) |

ND versus AD; age p=0.1971; PMI p=0.0244; frozen years p=0.4661. Carrier versus non-carrier; age p=0.5585; PMI p=0.0798; frozen years p=0.4712

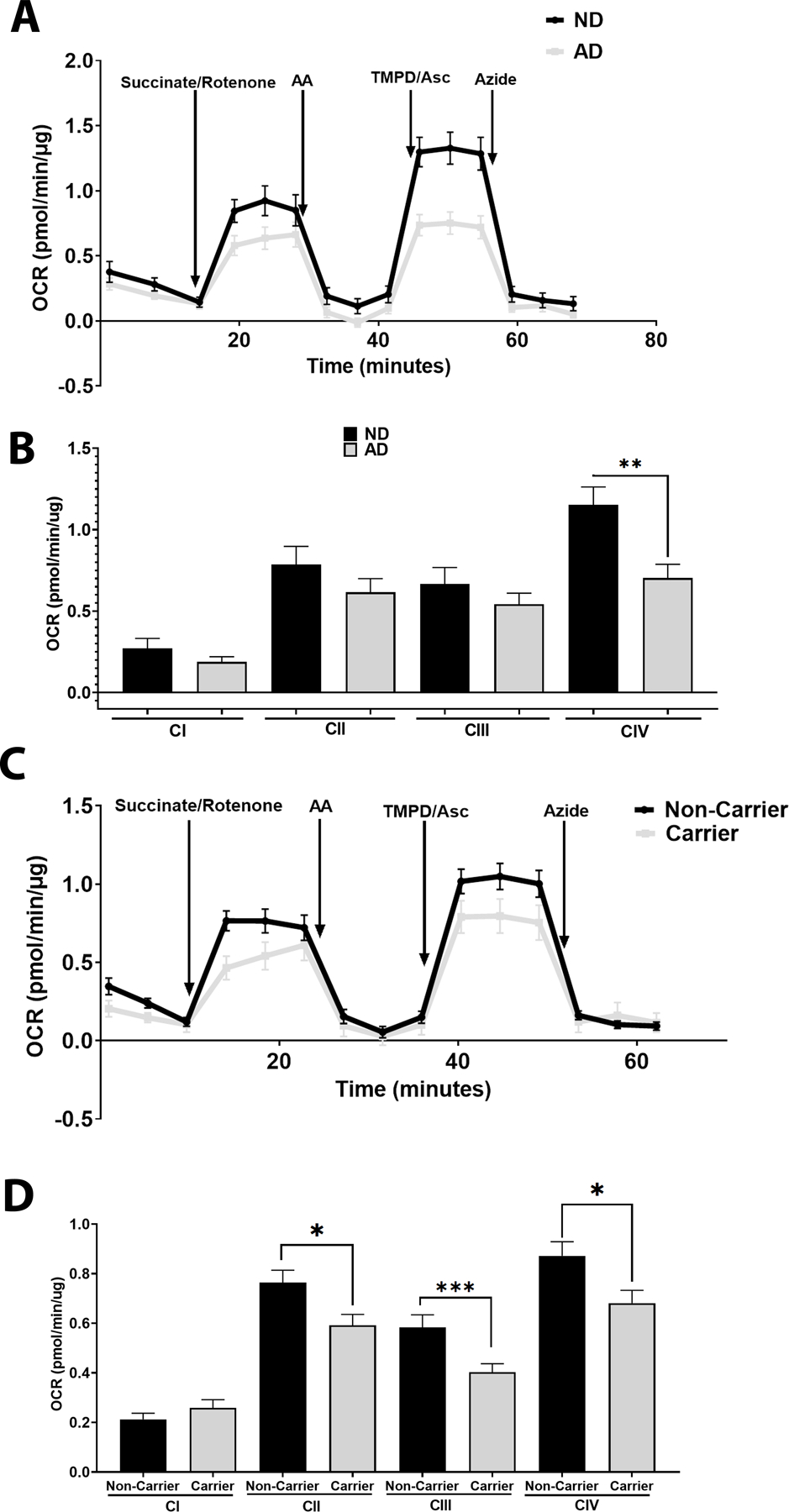

Using prior established protocols, we used a Seahorse Analyzer to examine respiratory chain function. ND and AD subjects were defined based on the NIA-AA Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change (ADNC). ND subjects were considered Not AD or Low ADNC, while AD subjects were considered intermediate to high ADNC. AD subjects had lower COX (CIV) activity when compared to ND subjects (Figure 1 A, B). Separating subjects by APOE ε4 carrier status revealed CII, CIII, and CIV deficits in carriers versus non-carriers (Figure 1 C, D). Means and confidence intervals are reported in Table S2.

Figure 1. Oxygen Consumption Rates in Postmortem Brain.

A. Oxygen Consumption Rates in ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. Representative tracing from the Seahorse XF Analyzer, n=11 ND vs n=12 AD. B. Quantification of A, showing complex I (before succinate/rotenone), II (after succinate/rotenone), III (succinate/rotenone with antimycin A subtracted), and IV (TMPD/Asc with azide subtracted) driven oxygen consumption rates, n=11 ND vs n=12 AD. C. Oxygen Consumption Rates in postmortem brain samples separated by APOE ε4 carrier status. Representative tracing from the Seahorse XF Analyzer, n=11 for carriers vs n=12 for non-carriers. D. Quantification of C, showing complex I (before succinate/rotenone), II (after succinate/rotenone), III (succinate/rotenone with antimycin A subtracted), and IV (TMPD/Asc with azide subtracted) driven oxygen consumption rates, n=11 for carriers vs n=12 for non-carriers. See materials and methods section for assay details and table 2 for demographics.

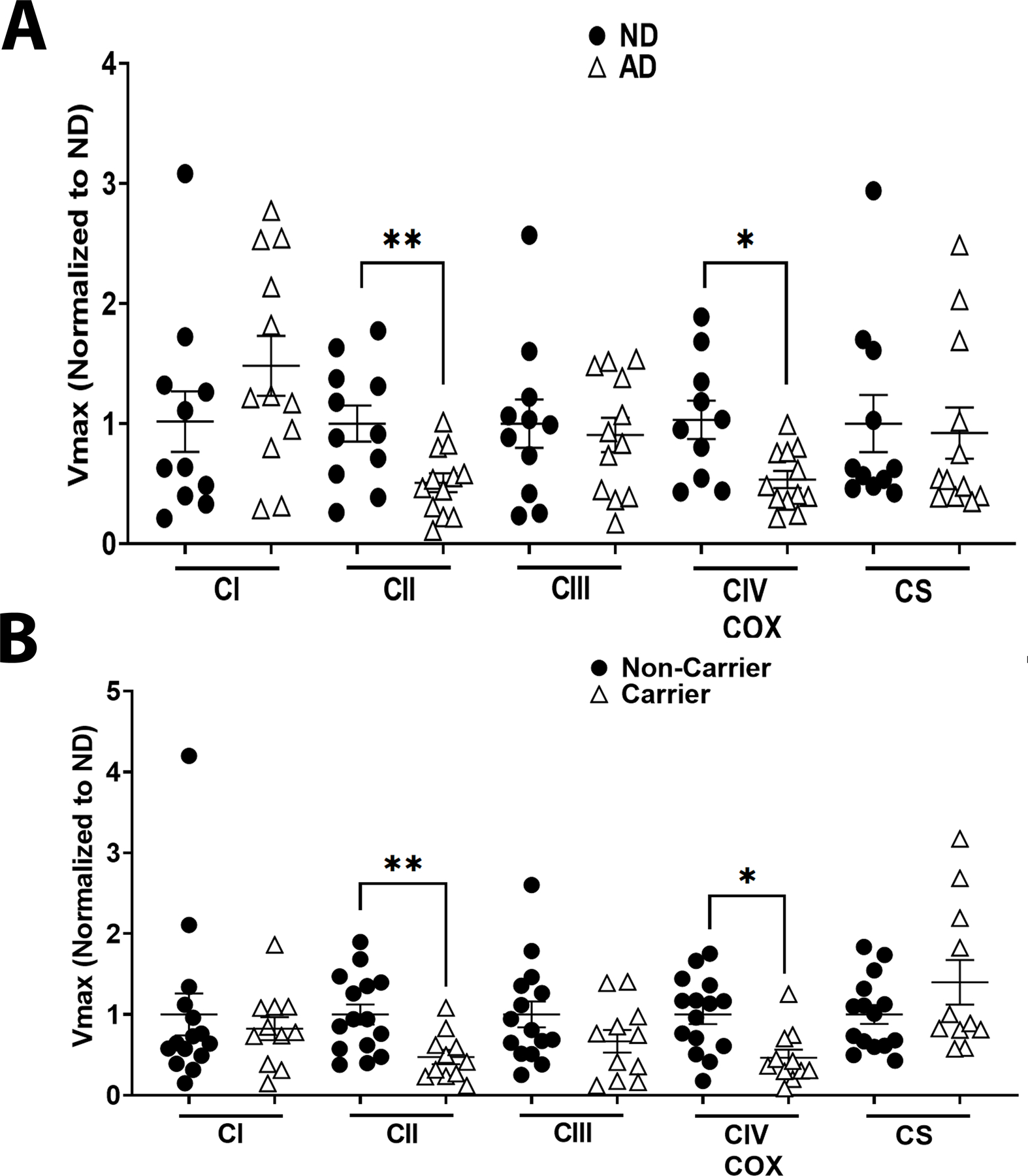

We next examined ETC function using standard spectrophotometric Vmax assays. AD subjects had lower CII and COX (CIV) Vmax when compared to ND subjects (Figure 2 A). No changes to CI, CIII, nor CS were observed between ND and AD subjects (Figure 2A). Separating subjects by APOE ε4 carrier status revealed CII and COX (CIV) deficits in carriers versus non-carriers (Figure 2A). No changes were observed for CI, CIII, or CS Vmax (Figure 2A). Means and confidence intervals are reported in Table S3.

Figure 2. ETC Vmax in Postmortem Brain.

A. Complex I, Complex II, Complex III, Complex IV, and CS Vmax from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples, n=11 ND vs n=12 AD. B. Complex I, Complex II, Complex III, Complex IV, and CS Vmax from postmortem brain samples separated by APOE ε4 carrier status, n=11 for carriers vs n=12 for non-carriers. See materials and methods section for Vmax assay details and table 2 for demographics.

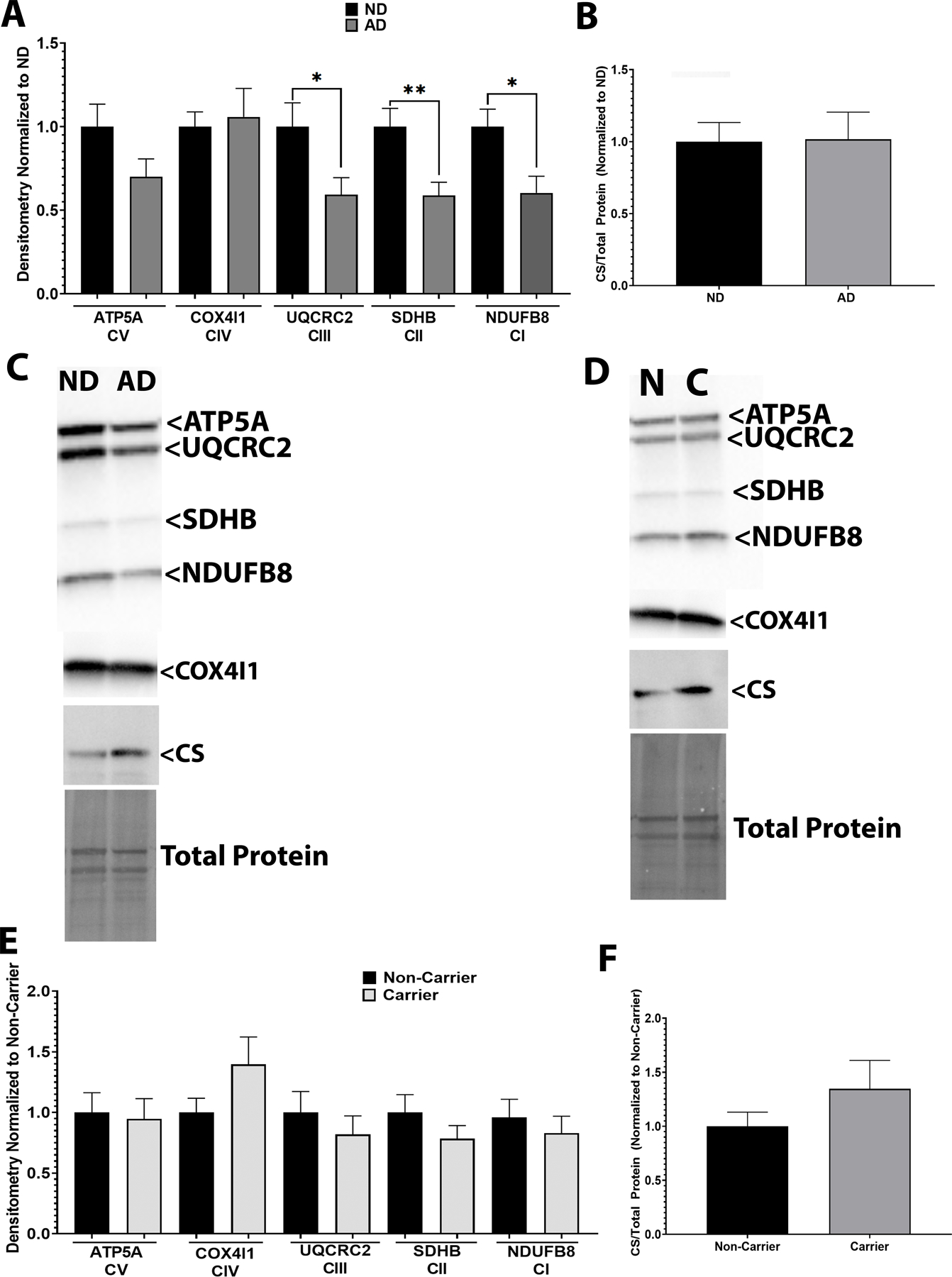

Protein expression of ETC components was measured via western blotting. AD subjects had lower expression of UQCRC2 (CIII), SDHB (CII), and NDUFB8 (CI) ETC components (Figure 3A-C). No changes were observed for COX4I1 (CIV), ATP5A, (ATP-synthase), or CS. We observed no changes in expression patterns when subjects were separated by APOE ε4 carrier status (Figure 3 D-F). Means and confidence intervals are reported in Table S3. Western blot images of all samples are shown in supplemental data (Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 3. ETC Protein Expression in Postmortem Brain.

A. Complex I-IV component expression from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. B. CS protein expression from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. C. Representative western blot images. n=11 ND vs n=12 AD D. Complex I-IV component expression from postmortem brain samples separated by APOE ε4 carrier status. E. CS protein expression from postmortem brain samples separated by APOE ε4 carrier status. F. Representative western blot images. n=11 for carriers vs n=12 for non-carriers. See materials and methods section for assay details, table 1 for antibody information, and table 2 for demographics.

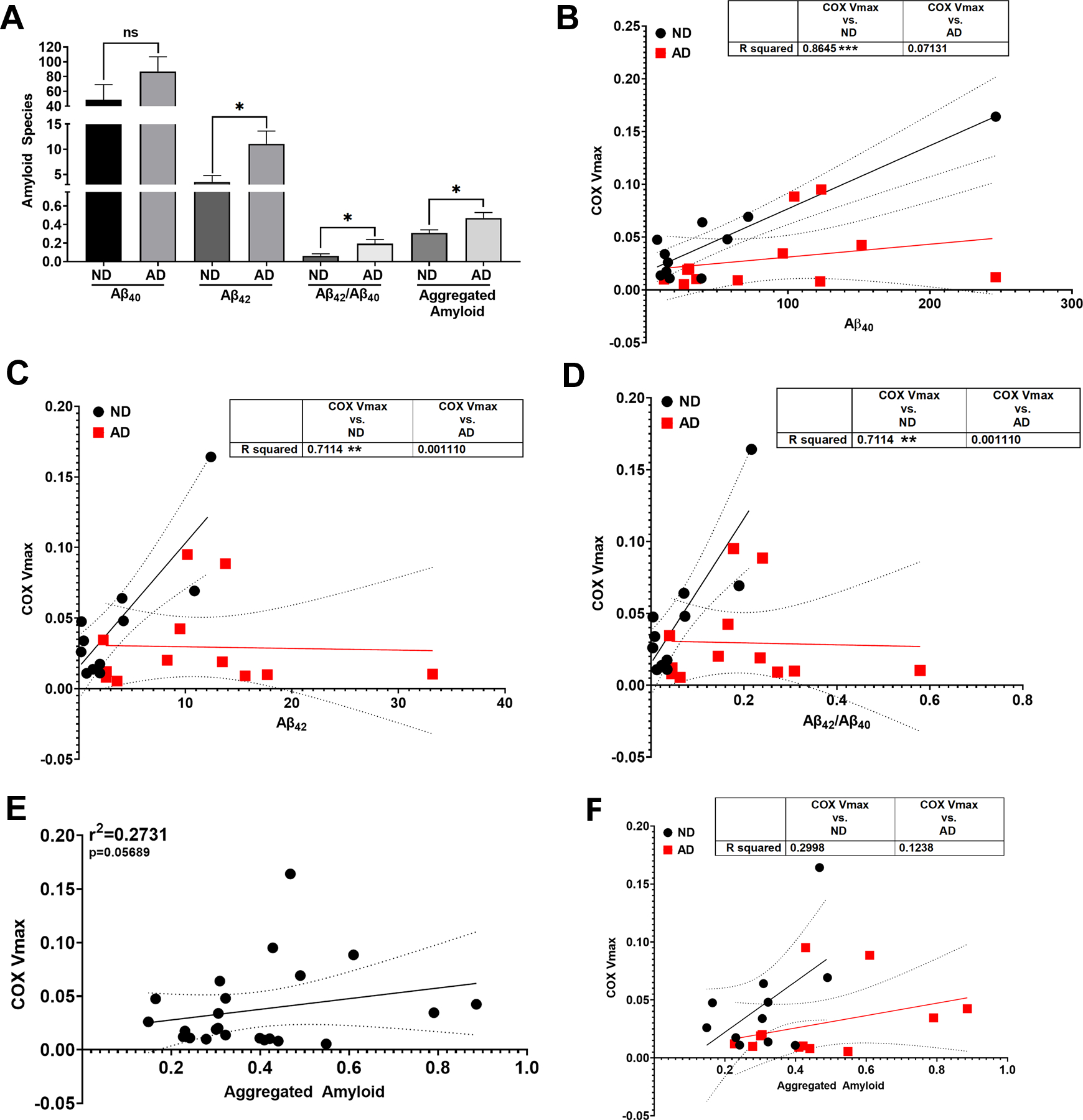

As expected, AD subjects had higher Aβ42, aggregated Aβ, and Aβ42/40 ratios but not Aβ40 (Figure 4A). Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ42/40 levels correlated positively with COX (CIV) Vmax in ND subjects (Figure 4 B-D). This relationship was not present in AD subjects, nor when data were separated by APOE ε4 carrier status (data not shown). A non-significant correlation is shown between aggregated Aβ and COX (CIV) Vmax (Figure 4E, p=0.05689). AD subjects had higher pTau181 levels (Table S5), but this did not correlate with COX Vmax (data not shown). Means and confidence intervals are reported in Table S5.

Figure 4. Relationship between COX Vmax and Aβ in Postmortem Brain.

A. Aβ species quantification from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. B. Correlation between COX Vmax and Aβ40 from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. C. Correlation between COX Vmax and Aβ42 from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. D. Correlation between COX Vmax and Aβ42/ Aβ40 from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples.E. Correlation between COX Vmax and aggregated amyloid from all brain samples. F. Correlation between COX Vmax and aggregated amyloid from ND versus AD postmortem brain samples. n=11 ND vs n=12 AD. See materials and methods section for assay details and table 2 for demographics.

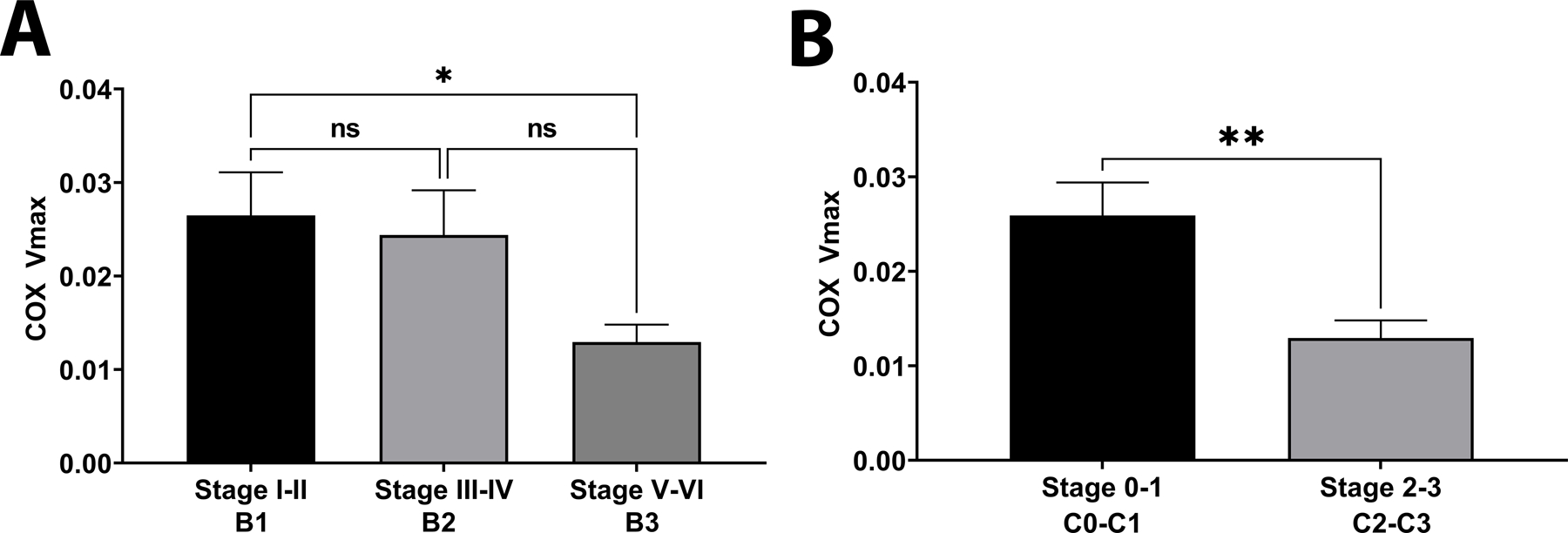

We examined COX Vmax with respect to AD neuropathological scores and scales. COX Vmax was reduced in subjects with Braak stages between V-VI (Figure 5A) and CERAD scores 2–3 (Figure 5B). Furthermore, there was no correlation between mitochondrial Vmax outcomes and PMI (reported in Table S6).

Figure 5. COX Vmax by Neuropathological Staging.

A. COX Vmax by Braak Staging; n=8, n=3, and n=11 for stage I-II, III-IV, and V-VI respectively. B. COX Vmax by CERAD score; n=11 per group. See materials and methods section for assay details and table 2 for demographics.

DISCUSSION

We report mitochondrial dysfunction in human postmortem AD brain consistent with other studies 29–31, 39–42. AD subjects showed reduced COX flux and Vmax with reduced complex II Vmax. When separated by APOE genotype, APOE ε4 carrier postmortem brain tissue had reduced COX flux and Vmax, reduced complex II flux and Vmax, and reduced complex III Vmax. We specially compared seahorse flux and Vmax assays and observed consistency for COX function across both assays. Our data further indicate that complex II and complex III integrity could be altered in both AD patients and APOE ε4 carriers.

Key differences between the novel seahorse assay and spectrophotometric Vmax assays exist. The measured output from the seahorse platform is oxygen consumption rate or oxygen tension in the buffer using a fluorescence-based reading. Vmax based assays typically measure the production of a metabolite indirectly. Differences were observed between Vmax and seahorse flux measures for Complex II between ND and AD subjects. The Vmax assay contained an inhibitor for COX/CIV and measured ubiquinol production indirectly through the reduction of DCPIP. Conversely the seahorse assay measures oxygen consumption in the presence of succinate. The observed differences between outcomes for the seahorse flux analysis and Vmax assays are due to the nature of the assays. This highlights the importance of assay design for future studies examining mitochondrial function in tissues. Utilization of the seahorse platform to obtain ETC flux analysis from postmortem tissues will allow further study of temporal mitochondrial changes in diseased states. This assay will be especially useful when tissue amounts are limited.

The role complex II deficits may play in AD are unknown and unreported. Complex II is encoded solely by nuclear DNA, unlike COX. In AD mouse models both complex II and COX function are reduced, and proteomics analysis of human AD brain shows reduced complex II subunit expression in familial subjects only 43, 44. Overall, the finding of changes to complex II in sporadic AD postmortem brain require independent verification in larger cohorts.

APOE ε4 is associated with bioenergetic and mitochondrial dysfunction in AD and aging 45. Young APOE ε4 carriers show mitochondrial dysfunction before AD onset 40. In addition, mouse models carrying humanized APOE ε4 have mitochondrial dysfunction in the absence of classic AD pathology 46–48. Proteolytic cleavage of APOE ε4 at its C-terminus creates a 272 amino acid peptide that localizes to mitochondria and can interfere with ETC function 4, 47. Our results show reduced Complex II, III, and COX function in APOE ε4 carriers and the exact mechanism of these findings will require further investigation.

We observed significant protein expression reductions for complexes I, II, and III in AD subjects but no changes in APOE ε4 carriers. It is of interest that no change in COX expression was observed between groups. Our assessment, however, only included a limited subset of ETC subunits. A past proteomics study reported changes to some subunits of complex I, II, III, and IV in early or late onset AD postmortem brain tissues 43. Altered protein expression of the ETC components is likely to impact flux measures.

Prior studies indicate COX is assembled differently in AD postmortem brain 49, 50. Of interest is that COX deficiency is observed systemically in AD and across numerous AD models 1, 29, 36, 38, 51, 52. COX Vmax deficits are reflected in skin and blood samples from AD subjects 36, 37, 53. AD subjects who carry an APOE ε4 allele show reduced COX Vmax in blood when compared to non-carrier AD subjects 36, 37. Overall, COX dysfunction is well documented in AD but its relationship with AD pathology is not well understood.

Neuropathological stages and scoring associated with COX Vmax deficits. In Braak stages V-VI significant reductions to COX Vmax were observed. Braak stages V-VI indicates neurofibrillary tangles throughout entorhinal, limbic, and neocortical structures. We did not observe a relationship between tau phosphorylation and COX function. However, within the scope of our study we only measured one tau phosphorylation site. Therefore, these findings require larger studies to explore this relationship adequately.

For CERAD neuropathological scoring, postmortem samples with moderate to frequent neuritic plaques had significant COX Vmax deficit. With postmortem brain samples it is difficult to assess cell type specific contributions to COX Vmax reductions, but it is expected that the bulk of cell mass will be from glial cells. Association with CERAD scoring suggests that loss of neurons and increasing neuritic plaques contribute to COX Vmax decline. Future work should elucidate the role of gliosis and neuronal loss in ETC functional changes in brain.

We examined how mitochondrial function, particularly COX Vmax, interacted with AD pathology. We observed a positive correlation between Aβ brain levels and COX Vmax in non-demented subjects. This relationship was not observed in AD nor APOE ε4 carriers. These findings suggest that higher COX Vmax is associated with higher Aβ levels. Our findings are consistent with studies in AD animal models. One prior study used genetic knockout of COX in neurons of a familial AD mouse model and found this reduced Aβ production and pathology 24. A separate study reduced mtDNA levels in an AD mouse model resulting in reduced COX activity and reduced Aβ pathology 25. A significant relationship between COX function and Aβ production/pathology is evident and could provide critical data as to why Aβ is generated.

We and others have reported strong relationships between APP processing, Aβ production, and mitochondrial function 13, 19, 44, 54, 55. Recently, we reported that mitochondrial membrane potential predictably alters Aβ production 26. COX is a major regulator of mitochondrial membrane potential and thus these findings contribute to our understanding of mitochondria/ Aβ relationships 56.

Further studies should assess the contributions of full-length APP and other APP processing products in mitochondrial function from postmortem brain samples. Several studies implicate full-length APP localization at mitochondria, with implications that is blocks the translocases of the outer and inner mitochondrial membrane 13. These prior studies indicated that full-length APP could induce changes to mitochondrial function13, 14, 22, however further study is required to understand the relationship between full-length APP and mitochondrial function.

Within our cohort the ND group had a significantly higher PMI than the AD group. However, the ND group consistently showed higher mitochondrial function parameters. This suggests this did not artifactually account for our outcomes, as a longer PMI in the ND group would predictably mitigate rather than accentuate differences with the AD group. More importantly, when we examined the relationship between PMI and COX Vmax, no correlation was observed. Our cohort also contained an uneven sex distribution, an issue we plan to address in larger studies as sex as a biological variable is important to consider in AD studies.

Overall, we report significant mitochondrial dysfunction in postmortem AD brain which is also associated with APOE genotype. Mitochondrial function interacts with Aβ levels and AD neuropathological staging/scores within our cohort. This study highlights the imperative need to understand the physiological role of the Aβ/mitochondria relationship in aging and AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Funding:

This study was supported by the Peg McLaughlin fund, the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center P30AG035982, and R00AG056600.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swerdlow RH, Koppel S, Weidling I, Hayley C, Ji Y, Wilkins HM. Mitochondria, Cybrids, Aging, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2017;146:259–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy PH, Oliver DM. Amyloid Beta and Phosphorylated Tau-Induced Defective Autophagy and Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husain MA, Laurent B, Plourde M. APOE and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Lipid Transport to Physiopathology and Therapeutics. Front Neurosci 2021;15:630502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin J, Reiman EM, Beach TG, et al. Effect of ApoE isoforms on mitochondria in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2020;94:e2404–e2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris JK, Uy RAZ, Vidoni ED, et al. Effect of APOE epsilon4 Genotype on Metabolic Biomarkers in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;58:1129–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barja G, Herrero A. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is inversely related to maximum life span in the heart and brain of mammals. FASEB J 2000;14:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertoni-Freddari C, Balietti M, Giorgetti B, et al. Selective decline of the metabolic competence of oversized synaptic mitochondria in the old monkey cerebellum. Rejuvenation Res 2008;11:387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertoni-Freddari C, Fattoretti P, Casoli T, Spagna C, Meier-Ruge W, Ulrich J. Morphological plasticity of synaptic mitochondria during aging. Brain Res 1993;628:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow RH, Hui D, Chalise P, et al. Exploratory analysis of mtDNA haplogroups in two Alzheimer’s longitudinal cohorts. Alzheimers Dement 2020;16:1164–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heggeli KA, Crook J, Thomas C, Graff-Radford N. Maternal transmission of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26:364–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews SJ, Fulton-Howard B, Patterson C, et al. Mitonuclear interactions influence Alzheimer’s disease risk. Neurobiol Aging 2020;87:138 e137–138 e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrieri G, Bonafe M, De Luca M, et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and APOE4 allele are non-independent variables in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Genet 2001;108:194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin MA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol 2003;161:41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devi L, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Mitochondrial trafficking of APP and alpha synuclein: Relevance to mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1802:11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contino S, Porporato PE, Bird M, et al. Presenilin 2-Dependent Maintenance of Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacity and Morphology. Front Physiol 2017;8:796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behbahani H, Shabalina IG, Wiehager B, et al. Differential role of Presenilin-1 and −2 on mitochondrial membrane potential and oxygen consumption in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J Neurosci Res 2006;84:891–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A, Pozzan T, Pizzo P. Presenilin 2 Modulates Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Coupling by Tuning the Antagonistic Effect of Mitofusin 2. Cell Rep 2016;15:2226–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Del Prete D, Suski JM, Oules B, et al. Localization and Processing of the Amyloid-beta Protein Precursor in Mitochondria-Associated Membranes. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55:1549–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansson Petersen CA, Alikhani N, Behbahani H, et al. The amyloid beta-peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:13145–13150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavlov PF, Wiehager B, Sakai J, et al. Mitochondrial gamma-secretase participates in the metabolism of mitochondria-associated amyloid precursor protein. FASEB J 2011;25:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez Sanchez MIG, Waugh HS, Tsatsanis A, et al. Amyloid precursor protein drives down-regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation independent of amyloid beta. Sci Rep 2017;7:9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pera M, Larrea D, Guardia-Laguarta C, et al. Increased localization of APP-C99 in mitochondria-associated ER membranes causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. EMBO J 2017;36:3356–3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidling IW, Wilkins HM, Koppel SJ, et al. Mitochondrial DNA Manipulations Affect Tau Oligomerization. J Alzheimers Dis 2020;77:149–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukui H, Diaz F, Garcia S, Moraes CT. Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in neurons decreases both oxidative stress and amyloid formation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:14163–14168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinto M, Pickrell AM, Fukui H, Moraes CT. Mitochondrial DNA damage in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease decreases amyloid beta plaque formation. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:2399–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkins HM, Troutwine BR, Menta BW, et al. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Influences Amyloid-beta Protein Precursor Localization and Amyloid-beta Secretion. J Alzheimers Dis 2022;85:381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acin-Perez R, Benador IY, Petcherski A, et al. A novel approach to measure mitochondrial respiration in frozen biological samples. EMBO J 2020;39:e104073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osto C, Benador IY, Ngo J, et al. Measuring Mitochondrial Respiration in Previously Frozen Biological Samples. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2020;89:e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosetti F, Brizzi F, Barogi S, et al. Cytochrome c oxidase and mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase (ATP synthase) activities in platelets and brain from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2002;23:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kish SJ. Brain energy metabolizing enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease: alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and cytochrome oxidase. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997;826:218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kish SJ, Bergeron C, Rajput A, et al. Brain cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 1992;59:776–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdlow RH. Mitochondria in cybrids containing mtDNA from persons with mitochondriopathies. J Neurosci Res 2007;85:3416–3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Committee NS. Coding Guidebook for the NACC Neuropathology Data Form, 11 ed2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wojtovich AP, Brookes PS. The endogenous mitochondrial complex II inhibitor malonate regulates mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels: implications for ischemic preconditioning. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1777:882–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo C, Long J, Liu J. An improved spectrophotometric method for a more specific and accurate assay of mitochondrial complex III activity. Clin Chim Acta 2008;395:38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkins HM, Koppel SJ, Bothwell R, Mahnken J, Burns JM, Swerdlow RH. Platelet cytochrome oxidase and citrate synthase activities in APOE epsilon4 carrier and non-carrier Alzheimer’s disease patients. Redox Biol 2017;12:828–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkins HM, Wang X, Menta BW, et al. Bioenergetic and inflammatory systemic phenotypes in Alzheimer’s disease APOE epsilon4-carriers. Aging Cell 2021;20:e13356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosconi L, de Leon M, Murray J, et al. Reduced mitochondria cytochrome oxidase activity in adult children of mothers with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;27:483–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker WD Jr., Parks JK. Cytochrome c oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease brain: purification and characterization. Neurology 1995;45:482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valla J, Berndt JD, Gonzalez-Lima F. Energy hypometabolism in posterior cingulate cortex of Alzheimer’s patients: superficial laminar cytochrome oxidase associated with disease duration. J Neurosci 2001;21:4923–4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke JR, Ribeiro FC, Frozza RL, De Felice FG, Lourenco MV. Metabolic Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Basic Neurobiology to Clinical Approaches. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;64:S405–S426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jadiya P, Garbincius JF, Elrod JW. Reappraisal of metabolic dysfunction in neurodegeneration: Focus on mitochondrial function and calcium signaling. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2021;9:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adav SS, Park JE, Sze SK. Quantitative profiling brain proteomes revealed mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Brain 2019;12:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhein V, Song X, Wiesner A, et al. Amyloid-beta and tau synergistically impair the oxidative phosphorylation system in triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20057–20062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson LA. APOE and metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 2020;154:131–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Area-Gomez E, Larrea D, Pera M, et al. APOE4 is Associated with Differential Regional Vulnerability to Bioenergetic Deficits in Aged APOE Mice. Sci Rep 2020;10:4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura T, Watanabe A, Fujino T, Hosono T, Michikawa M. Apolipoprotein E4 (1–272) fragment is associated with mitochondrial proteins and affects mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. Mol Neurodegener 2009;4:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farmer BC, Kluemper J, Johnson LA. Apolipoprotein E4 Alters Astrocyte Fatty Acid Metabolism and Lipid Droplet Formation. Cells 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker WD, Jr. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1991;640:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker WD Jr., Filley CM, Parks JK. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1990;40:1302–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cardoso SM, Proenca MT, Santos S, Santana I, Oliveira CR. Cytochrome c oxidase is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease platelets. Neurobiol Aging 2004;25:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, Cassarino DS, et al. Mitochondria in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol 1998;153:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curti D, Rognoni F, Gasparini L, et al. Oxidative metabolism in cultured fibroblasts derived from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. Neurosci Lett 1997;236:13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhattacharyya R, Black SE, Lotlikar MS, et al. Axonal generation of amyloid-beta from palmitoylated APP in mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Cell Rep 2021;35:109134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkins HM, Swerdlow RH. Amyloid precursor protein processing and bioenergetics. Brain Res Bull 2017;133:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pacelli C, Latorre D, Cocco T, et al. Tight control of mitochondrial membrane potential by cytochrome c oxidase. Mitochondrion 2011;11:334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.