Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), is an effective form of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) prevention for people at potential risk for exposure. Despite its demonstrated efficacy, PrEP uptake and adherence have been discouraging, especially among groups most vulnerable to HIV transmission. A primary message to persons who are at elevated risk for HIV has been to focus on risk reduction, sexual risk behaviors, and continued condom use, rarely capitalizing on the positive impact on sexuality, intimacy, and relationships that PrEP affords. This systematic review synthesizes the findings and themes from 16 quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies examining PrEP motivations and outcomes focused on sexual satisfaction, sexual pleasure, sexual quality, and sexual intimacy. Significant themes emerged around PrEP as increasing emotional intimacy, closeness, and connectedness; PrEP as increasing sexual options and opportunities; PrEP as removing barriers to physical closeness and physical pleasure; and PrEP as reducing sexual anxiety and fears. It is argued that positive sexual pleasure motivations should be integrated into messaging to encourage PrEP uptake and adherence, as well as to destigmatize sexual pleasure and sexual activities of MSM.

Keywords: PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis, pleasure, sexual satisfaction

Introduction

Advances in research and treatment for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) have transformed an HIV diagnosis from a death sentence to a manageable chronic illness for those with access to testing, treatment, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), with the HIV-related death rate in the United States (U.S.) falling by half between 2010 and 2018 (Bosh et al., 2020). Globally, new HIV diagnoses have dropped 30% in the past ten years, with AIDS-related deaths nearly cut in half since 2010 (UNAIDS, 2021). However, despite medical advances and broadened knowledge about HIV transmission, HIV incidence has remained stagnant in much of the world, with new global HIV infections ranging from 1.5 million to 1.8 million annually (UNAIDS, 2021), and new HIV infections in the U.S. ranging from 37,000–40,000 annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). These facts remain troubling for HIV researchers, health care practitioners, and individuals at risk of exposure to HIV.

The tools for HIV prevention dramatically expanded in 2012 when the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drug Truvada for men who have sex with men (MSM), which effectively lowered the risk of HIV seroconversion among HIV-negative persons (FDA, 2012). PrEP is a pill taken by individuals who are HIV-negative that reduces the risk of contracting HIV by 99% when taken as prescribed (CDC, 2021b). Since 2012, PrEP has become available in hundreds of countries, contributing to a global increase in PrEP use, and PrEP eligibility in the U.S. has expanded to include a wider range of people at risk for HIV, including persons who report any acts of condomless sex (Schaefer et al., 2021). A subsequent iteration of PrEP has aimed to reduce side-effects and improve efficacy when a daily dose has been missed (FDA, 2019).

There are several other efficacious HIV prevention methods including Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP), a medication taken after potential exposure to HIV, but it is only recommended for use in emergency situations (CDC, 2021a). The U=U campaign (Undetectable = Untransmittable) and Treatment as Prevention (TasP) conceptualize that when an individual who is HIV-positive initiates and adheres to ART to lower their viral load to undetectable levels, they are actively preventing HIV transmission (Kalichman, 2013; Rendina et al., 2020). Negotiated safety is an additional HIV prevention method, in which there is an explicit agreement with established boundaries regarding condom use or exclusivity in the partnership (Kippax et al., 1993, 1997; Leblanc et al., 2017). These methods can be highly effective tools for HIV risk reduction even when engaging in condomless anal sex (Kippax & Holt, 2016), although each method requires reliance and trust on a sexual partner to be aware of their HIV-positive status, to be adherent to ART to achieve an undetectable viral load, or to have open communication about their sexual behaviors with others. These methods may pose further challenges in the U.S., as many MSM living with HIV are unaware of their positive status, and ART adherence remains difficult for many individuals receiving treatment (CDC, 2018).

PrEP is not without challenges, as there are several structural, financial, and social stigma barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence (Guyonvarch et al., 2021; Mayer et al., 2020; Sullivan & Siegler, 2018), the scope of which vary across sociodemographics, risk factors, jurisdictions, and location. However, this review focuses primarily on PrEP, as PrEP has several notable benefits including long-term use, allowing individuals on PrEP to advocate and be responsible for their own sexual health without reliance on negotiations with a partner, and freedom to engage in sexual activities without knowing the HIV status of their sexual partners.

While PrEP’s efficacy when taken correctly has been demonstrated, PrEP uptake and adherence has lagged worldwide (Owens et al., 2019; Sidebottom et al., 2018). Although the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a 70% increase in PrEP users from 2018 to 2019, the total number of individuals who received at least one dose of oral PrEP in 2019 was only 630,000, with most in the U.S. (37%) and Africa (36%) (WHO, 2021). This figure falls considerably short of the number of persons at high risk for HIV who are recommended to begin PrEP based upon WHO guidelines.

Campaigns promoting PrEP have predominately focused on HIV prevention and reducing the risk of HIV to motivate individuals at elevated risk for HIV to adopt PrEP as a risk reduction strategy (Owens et al., 2019). This risk-focused messaging often fails to acknowledge studies on motivations for PrEP uptake which have found that greater sexual freedom, not merely minimization of sexual risk, may underlie decisions to seek PrEP (Ranjit et al., 2019, 2020; Zimmerman et al., 2019). Ranjit et al. (2019, 2020) have posited a dual motivation model to increase PrEP uptake, outlining a Protection Motivation Pathway derived from a desire to protect oneself from risk, often in the context of safe sex fatigue; and the Expectancy Motivation Pathway, derived from a desire for more satisfying and pleasurable sexual experiences. Ranjit et al. (2020) and Zimmerman et al. (2019) found that among samples in both the U.S. and Ukraine, persons may possess a mixture of motivations, both personal and contextual, such as self-efficacy for adherence, individual risk profile, sexual situations, and desire for improved physical and mental well-being. Similarly, Zimmerman et al. (2019) found that these motivations may shift based upon relationship status and other contextual factors. These studies support the rationale that in addition to sexual health motivations, embracing the pursuit of sexual pleasure as a motivator for PrEP uptake may positively influence PrEP adoption.

Paradoxically, PrEP messages that target greater sexual pleasure and sexual freedom may collide with PrEP stigma, as PrEP stigma is grounded in large part in moralization against sexual pleasure, casual sexual encounters, and sexual exploration as being inherently negative (Calabrese & Underhill, 2015). Research examining barriers to PrEP adoption by MSM has found PrEP stigma to be a predominant impediment to willingness to adopt PrEP, as PrEP stigma incorporates stigma toward sexual minorities, social stigma pertaining to certain sexual behaviors and stigma against sexual promiscuity (Eaton et al., 2017; Girard et al., 2019; Grace et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2018; Quinn et al., 2020). Qualitative interviews and focus groups of MSM reflect persistent stigma experienced within gay communities themselves, as opposed to wider societal views. Responses from the focus groups were organized around concepts of social risk, immoral promiscuity, responsibility, and perceived irresponsibility (Girard et al., 2019; Quinn et al., 2020). Unfortunately, focus on stigma has often overshadowed the sexual benefits of using PrEP; namely, less sexual anxiety, more sexual pleasure, and increased sexual intimacy. In some respects, PrEP stigma has translated to stigmatizing sexual pleasure, which undermines the positive health and well-being benefits of sexuality.

Sexual satisfaction, distinct from sexual function, frequency, and orgasm, has been found to correlate with measures of well-being as well as physical health (Diamond & Huebner, 2012; Flynn, et al., 2016; Laumann et al., 2006; Rosen & Bachmann, 2008; Stephenson & Meston, 2015). In these studies, sexual satisfaction is a subjective concept, rather than an objective counting of sexual behaviors or function, such that sexual satisfaction equates with “an individual’s subjective evaluation of their sexuality” (Castañeda, 2013, p. 25), or as defined by Lawrance and Byers (1995) as, “an affective response arising from one’s subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions associated with one’s sexual relationship” (p. 268). Global endorsements of sexual pleasure as an important component of sexual health and overall well-being have emerged as well (Ford et al., 2019), framing sexual pleasure as a matter of public health, thus expanding sexuality discourse beyond disease prevention or sexual dysfunction. However, despite calls for greater coordination of sexual health initiatives by the U.S. Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002; Satcher, 2013), progress towards sexual positivity and sexuality as a component of well-being has been hampered by social constraints, stigma, and moralistic concerns (Ford et al., 2017). Further, as articulated in the WHO’s current working definition, sexual health is:

…a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. (WHO, 2002) (Emphasis added).

The World Association for Sexual Health (WAS) elevated the importance of sex positivity and pleasure even higher, officially declaring sexual pleasure integral to sexual health, holistic health, and overall well-being (WAS, 2019).

Remarkably, HIV prevention research and discussions of sexual pleasure do not ordinarily intersect, despite this substantial body of research connecting sexual satisfaction with overall well-being and improved health outcomes. The medicalization of HIV prevention has been soundly criticized by some as bereft of sexuality and pleasure, framing sexual behavior in terms of risk and barely considering sexual acts themselves as part of the human drive for pleasure, connection, intimacy, self-discovery, and even adventure (Auerbach & Hoppe, 2015; Calabrese & Underhill, 2015; Race, 2015). Public health researchers have endorsed advocating for rights to sexual pleasure as a matter of well-being for all sexual orientations (Boone & Bowleg, 2020; Gruskin & Kismodi, 2020; Landers & Kapadia; 2020; Pitts & Greene, 2020). The right to sexual pleasure includes being “sex positive,” acknowledging broad sexual diversity in activities, orientation, and practices. In short, sexual pleasure in and of itself, distinct from the biological effects of physical stimulation, may improve well-being psychologically, mentally, and physically. Entitlement to sexual pleasure should be recognized as a right of sexual minority men, which can be substantially benefited by access to PrEP (Boone & Bowleg, 2020).

To assess the state of the science and guide future research, we conducted a systematic review of research examining sexual pleasure as it relates to PrEP use. Our aim was to synthesize qualitative and quantitative studies examining PrEP motivations and benefits, focusing on enhanced sexuality, sexual pleasure, sexual quality, sexual satisfaction, and sexual experiences. Our approach was directed toward gaining a broader understanding of the extent to which sexual pleasure and PrEP are related, and to better understand the extent to which framing messages about sexual pleasure and PrEP could increase both uptake and adherence.

Method

Search Strategy

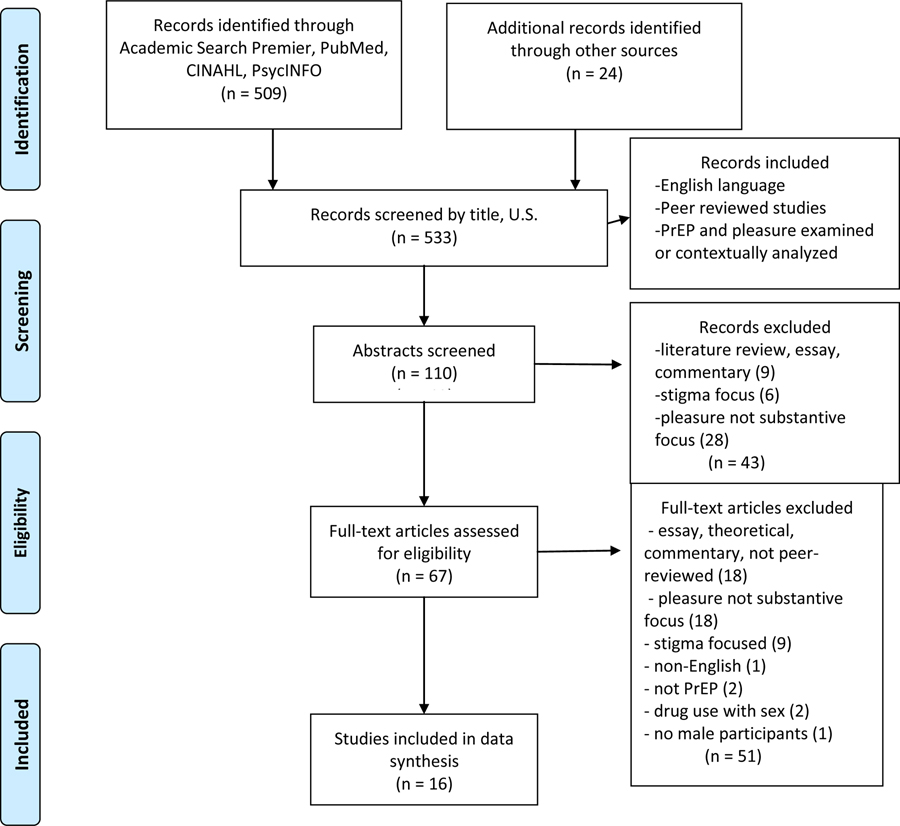

A systematic literature review was conducted by searching PubMed, Academic Search Premier, American Psychological Association (APA) PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases to identify peer-reviewed articles examining PrEP use and sexual pleasure in accordance with updated PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2020). Searches combined the following terms: PrEP OR preexposure prophylaxis OR pre-exposure prophylaxis AND pleasure OR satisfaction OR sexual quality OR sexual well-being OR sexual wellbeing OR intimacy OR intimate relationships. Our search was limited to English language articles involving human participants. Articles were located through September 15, 2020, with no publication date restriction in order to conduct the most comprehensive review possible. References in articles selected for potential inclusion were also reviewed, and the Google Scholar database was used to check citations for additional articles. The combined search of the databases and additional sources yielded 505 records. The 505 records found were screened by title for inclusionary criteria, resulting in 110 abstracts to be reviewed. Inclusion criteria were as follows: English language, peer reviewed studies, PrEP and sexual pleasure specifically or substantively examined in the results analyzed. Review of the 112 abstracts resulted in 45 records excluded either because they were literature reviews, essays, or commentaries (9); stigma focused (6); or pleasure was not a significant focus (30). Thereafter, 67 articles were fully reviewed, resulting in 16 articles being chosen for final inclusion; one study of women was excluded from formal review as the themes were distinct from those expressed by men. Reasons for exclusion of 51 full text articles were: essays, theoretical, commentary or not peer-reviewed (18); not substantively focused on pleasure (18); stigma focused (9); non-English (1); not PrEP (2); examined drug use with sex (2); and no male participants (1). A revised version of the PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram was used to illustrate the search, review, inclusion, and exclusion process (Moher et al., 2009) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Studies Examining Pleasure, Sexual Satisfaction, and PrEP.

Because most of the included studies were either qualitative or mixed methods, the initial stage of data extraction involved discerning themes emerging across studies and then assessing those themes with the quantitative data, undertaken by the first author, and confirmed after independent analysis by the second first author. Table 1 synthesizes the data from all of the studies to examine study and participant characteristics, design, emergent themes, and findings. The studies were reviewed by both first authors for quality using the MMAT for coding purposes (Hong et al., 2018); all of the included studies were determined to range from excellent to acceptable quality, with no studies falling into the low-quality category.

Table 1:

Overview of Reviewed Studies

| Study | Location | Recruitment | Participant Characteristics* | Sexual Orientation | HIV Status | PrEP Status | Study Design | Themes Regarding PrEP Use | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1. Gamarel & Golub (2015) | New York, NY; USA | Flyers, outreach, participant referral January 2012 - October 2013 |

1. N=164 2. 18–61; M=32.49 (SD=10.32) 3. Men=100% 4. White=66; Black=50; Latino=36; Other=12 5. 100% Partnered |

100% MSM: Gay=114; Bisexual=38; Other=12 | HIV-negative: 100% Partner Status: unknown=17; think positive=124; positive=23 |

Not on PrEP: 100% | Cross-sectional surveys and in-person interviews (verbal quantitative data collection) (Quantitative) | Perceived HIV risk HIV testing behavior Sexual risk and substance use behavior Condom use motivation PrEP adoption intentions |

Intimacy Intimacy interference motivations predicted willingness to adopt PrEP; physical pleasure interference motivations did not. Intimacy interference motivations improved model fit over CAS with outside partners and HIV risk perception with PrEP adoption intentions. Intimacy motivations were not found among single MSM. |

| 2. Collins et al. (2017) | Seattle, WA; USA | Flyers with local PrEP providers July - August 2014 |

1. N=14 2. 26–66 3. Men=13; Transgender=1 4. White=12; Black=1; Latino=1 5. NR |

100% MSM | HIV-negative: 100% | On PrEP: 100% | Semi-structured interviews (Qualitative) | Desire for safer CAS Reduced anxiety and shame Improved sexual satisfaction Stigma of PrEP use within gay community (e.g., promiscuous, irresponsible, risk taker) Stigma of PrEP use in healthcare settings |

Intimacy Those in committed serodiscordant relationships more likely to use PrEP to improve intimacy. Sexual Anxiety and Fears PrEP relieved psychological burden of HIV risk and improved self-efficacy and body control. On PrEP, participants reported: less fear, anxiety, panic; more satisfaction, connectivity, sexual liberation, peace of mind. |

| 3. Grace et al. (2018) | Toronto; Canada | PrEP users from Canadian demonstration project November 2014 - June 2016 (PrEP approved in Canada February 2016) |

1. N=16 2. 20–60; M=37.6 (SD=NR) 3. Men=15; Transgender=1 4. White=11; Black=1; Asian=1; Indigenous=1; Other=2 5. NR |

100% MSM or Gay | HIV-negative: 100% | On PrEP: 100% | Focus groups, In-depth interviews (N=5) (Qualitative) | PrEP use as sexually liberating Equal access to healthy pleasurable sex PrEP-related stigma HIV-related stigma PrEP as revealing structural stigma |

Sexual Options "Equality of access to healthy sex that straight people already have" Empowering with HIV-positive partner. Sexual Anxiety and Fears Liberation from fear of CAS. Sex allowed to be enjoyable again. Other Reduced stigma around sex with HIV-positive gay men; no need to ask about HIV status. |

|

4.

Hughes et al. (2018) |

San Francisco, CA; Miami, FL; USA | Sub-study of multi-site PrEP demonstration project May 2014 - August 2015 |

1. N=32 (N=15, San Francisco; N=17, Miami) 2. 24–66; M=40 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. White=13; Black=5; Latino=12; Asian=1; Mixed=1 5. NR |

100% MSM | NR | On PrEP: 100% | Semi-structured interviews (Qualitative) | Scheper-Hughes & Locke's (1987) "Three bodies" concept Individual body/selves Social bodies on PrEP Perspectives from the body politic Integration of sexuality and self |

Sexual Options PrEP use allowed for sexual liberation and greater self-efficacy. Sexual Anxiety and Fears Influence of PrEP on sexual behaviors may be indirect by reducing anxiety around CAS. Meanings attributed to PrEP use often emotionally charged, bittersweet, reduced fear. Other Sexual decision making as part of social interactions within and outside of relationships. PrEP as a way to prevent HIV understood differently across ages. |

| 5. Malone et al. (2018) | Boston, MA; USA | Urban health center and community-based organizations | 1. N=40 (20 couples) 2. 29–45; M=33 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. White=32; Black=5; Other=3 5. 100% Partnered (M=5.5 years) |

100% MSM | HIV-negative: 16 couples HIV-discordant: 4 couples |

On PrEP: 52.5% (N=21) | Semi-structured interviews (Qualitative) | Foundation for sexual agreements and improving communication Emotional monogamy PrEP and sexual agreements PrEP and risk mitigation of consequences of partner's risk behaviors |

Sexual Options PrEP to reduce HIV risk individually and for their committed relationship. PrEP helping relationships to be sexually open/lower risk of sexual agreements. Anxiety and Fears PrEP helped to restore trust, confidence, and safety in relationships. Using PrEP for reduced anxiety/peace of mind. Other Using PrEP highlighted risk awareness and did not result in risk compensation. Prioritizing HIV-prevention. |

| 6. Gamarel & Golub (2019) | New York, NY; USA | Flyers, outreach, participant referral, SPARK PrEP demonstration project April 2013 - October 2013 |

[Study 1/Study 2] 1. N=51/145 2. 19–61; M=32.14 (SD=NR)/21–63; M=34.30 (SD=NR) 3. Men=41/145 4. White=20/77; Black=18/16 5. 100% Partnered |

100% Gay or Bisexual | HIV-negative: 100% | Not on PrEP: 100%/66.9% (N=97) | Both Studies: Computer-assisted interview surveys (Quantitative) |

Study 1: Closeness discrepancy (IOS) Condom intimacy interference Perceived HIV risk Sexual risk behavior PrEP adoption intentions Study 2: Relationship quality Sexual satisfaction PrEP uptake |

Intimacy Majority in both samples desired more closeness in their relationships. Study 1: Closeness discrepancy scores and intimacy interference positively associated with PrEP intentions. Study 2: Desiring more closeness predicted PrEP uptake. Study 2: Actual closeness and intimacy interference predicted PrEP uptake, but no interaction (separate motives). Other Study 2: Open sexual agreements not inherently risky. |

| 7. Mabire et al. (2019) | France | Men from ANRS-IPERGAY PrEP trial 2014 |

1. N=45 2. 20–67; M=35 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. NR 5. Partnered=17 |

100% MSM: Gay=40; Undefined=5 |

HIV-negative: 100% | On PrEP: 100% | Semi-structured interviews (Qualitative) | Relationship with condoms Intimacy and pleasure Achieving better sexual quality of life |

Intimacy PrEP allows greater physical and psychological intimacy. Ending condom use a sign of intimacy. Sexual Options PrEP allows choice of sexual position. Physical Closeness Condoms as reducing sexual pleasure, in terms of activity and putting them on (reduced "fear of loss of performance"). Sexual "fulfilment as opposed to frustration". Other Sexual agency and control over risk. |

| 8. Nakku-Joloba et al. (2019) | Uganda | Partners Demonstration Project (PrEP) | 1. N=186 (93 couples) 2. 25–37 3. Men=143; Women=43 4. Black=100% 5. 100% Partnered |

MSM, Heterosexual (number NR) | HIV-serodiscordant couples: 100% | On PrEP: 79.5% (N=148) | Interviews (274 total; 148 couples; 126 individuals) (Qualitative) | PrEP alleviated threat to relationships PrEP as a way to stop using condoms PrEP allows serodiscordant relationships to continue |

Intimacy/Physical Closeness PrEP to make it "safe" for "live sex" to increase intimacy and closeness. Reluctance to use PrEP and condoms together, as undermining intimacy. Sexual Options/Sexual Anxiety and Fears PrEP reduced fear and brought back hope in making future plans for family. Other PrEP increased sexual desire. PrEP restores hope in relationships. |

| 9. Whitfield et al. (2019) | National Cohort; USA | Cohort of Gay Black men from the "One Thousand Strong" longitudinal study | 1. N=137 2. 18–45+; M=35.98 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. White=96; Black=15; Latino=15; Other/Multiracial=11 5. Partnered=63 |

100% MSM, Gay, Bisexual | HIV-negative: 100% | Baseline: 0% (entire sample never used PrEP) Final Follow-up: Currently on PrEP: 88.3% |

Survey data (Quantitative) | Multidimensional sexual self-concept Measured sexual satisfaction, esteem, and anxiety PrEP use |

Physical Closeness CAS with casual partners and being in a relationship predicted sexual satisfaction. Sexual Anxiety and Fears PrEP use predicted lower sexual anxiety, greater for older age participants. Other PrEP use did not predict sexual esteem or sexual satisfaction (Note: sexual satisfaction scale did not directly assess physical pleasure). |

| 10. da Silva-Brandeo & Zollner Ianni (2020) | Facebook posts; primarily USA | PrEP users in Facebook discussion group | 1. NR 2. NR 3. NR, mainly men 4. NR 5. NR |

100% MSM, Gay, Bisexual | NR | On PrEP: 100% | Analysis of Facebook posts (Qualitative) | Experience of individuals on PrEP Production of sexual desires and/or pleasures User individuation and identity expression Social context of PrEP |

Sexual Options CAS is a possibility; change in forms of pleasure; bareback sex can be responsible, not libertarian. Sexual choices not framed by risk. Physical Closeness Allows experience of natural skin on skin sex, as opposed to "unnatural" (some caution with the term as inferring deviant sex). Other Potential for greater positivity towards sex: sex equaling pleasure instead of risk. |

| 11. Gamarel & Golub (2020)** | New York, NY; USA | Community-based service organizations, support groups, drug treatment centers, SPARK PrEP demonstration project January 2014 - October 2015 |

1. N=145 2. 21–63; M=34.30 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. White=77; Black=16; Latino=29; Other=23 5. Partnered=79 (at follow-up) |

100% MSM: Gay=110; Bisexual=19; Other=15 |

HIV-negative: 100% Partner Status: HIV-negative: 84 HIV-positive: 48 Unknown: 13 |

On PrEP: 66.9% (N=97) | Open-ended survey questions, survey data (Mixed) | PrEP adoption Perceptions of goal congruence Relationship quality Sexual satisfaction Risk perception Sexual behavior Sexual goals and priorities Relation focused vs. self-focused |

Intimacy Intimacy goals to be connected to partner more relationship focused; intimacy goals included sexual freedom in relationships. Sexual Options Satisfaction goals more self-focused: "to explore all types of pleasure". Other Higher goal congruence, HIV-positive status of partner, higher sexual satisfaction predicted PrEP adoption. Prevention goals of sexual health more self-focused, some for protection of partner. |

| 12. Harrington et al. (2020) | London; United Kingdom | Social media advertisement on a United-Kingdom-based non-profit community group | 1. N=13 2. 26–56; M=37 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. White=9; Black=2; Indian=1; Other=1 5. NR |

100% MSM | HIV-negative: 100% | On PrEP: 100% | Semi-structured interviews (Qualitative) | PrEP and condom use Lessened anxiety around HIV Increased intimacy and pleasure Sense of sexual liberation Ease of using PrEP Activism by early adopters of PrEP |

Sexual Options Reduction of risk of CAS; less emphasis on condom use; condom use at request of non-PrEP partner. PrEP increased sexual agency, more freedom to explore sexuality, less inhibited. Sexual Anxiety and Fears Sexual encounters more pleasurable with less anxiety, more intimacy and physical pleasure. |

| 13. Philpot et al. (2020) | Australia | Online advertisements on social media platforms, popular gay and bisexual dating apps 2017 (just prior to PrEP approval in Australia) |

1. N=1404 2. 16.5–50+ 3. Men=100% 4. NR 5. NR |

100% MSM | HIV-negative or untested: 100% | Mixed (number NR) | Survey/online longitudinal study, free text responses (Mixed) | Positive social impact Overcoming fear and anxiety Enhancing sexual pleasure and opportunity Negative social impact |

Sexual Options/Physical Closeness More "natural" sex, more sexual pleasure, more sexual options. Sexual Anxiety and Fears Concern for increase in CAS; false sense of security around STIs. Other Redefining safe sex and potential to reduce HIV stigma. Lessening sexual inhibitions. Potential impacts on gay community to be seen as irresponsible or lazy; encouraged promiscuity. Pressure to engage in socially undesirable sexual behavior. |

| 14. Quinn et al. (2020) | Milwaukee, WI; Minneapolis, MN; Detroit, MI; Kansas City, MO; USA | Community organizations in study cities (e.g., flyers in clinics, HIV testing centers, LGBT community centers, local hangout locations), targeted Facebook ads 2018 |

1. N=36 2. 20–30; M=25.9 (SD=NR) 3. Men=100% 4. Black=36 5. Partnered=15 |

100% MSM: Gay=25; Bisexual=5; Other=6 |

HIV-negative: 100% | Current PrEP user: 75% (N=27) Former PrEP user: 25% (N=9) |

Focus groups (Qualitative) | Reduced sexual and HIV anxiety Increased sexual freedom Facilitated sexual relationships with PLWH |

Sexual Options Freedom to consider new sexual positions, less risk when bottoming. Sexual Anxiety and Fears PrEP reduced anxiety around having sex, which existed even with condoms. PrEP safety net includes increased HIV testing, can explore sexuality. Positive sero-discordant relationships, reduced HIV stigma, increased comfort. Other CAS viewed as "sexier". Increased control over sexual risk, not having to rely on partner. PrEP as showing love for HIV-positive partners. |

| 15. Reyniers et al. (2020) | Belgium | PrEP demonstration project October 2015 - May 2018 |

Surveys/ Interviews 1. N=200/22 2. M=38/37 3. Men=197; Transgender Women=3/Men=22 4. White=178/19; Arabic/Latino=22/3 5. Partnered=90/4 |

100% MSM: Gay=144/17 |

HIV-negative: 100% | On PrEP: 100% | Surveys, interviews (Mixed) | Evaluation of sex life Healthy sexuality Sexual risk behavior Feeling better protected against HIV Improved sexual health Reduced condom use More sex and more anal sex Experimentation with new sexual behaviors |

Sexual Options Ability to seek out more enjoyable sex. More sex, more anal sex, sexual experimentation. Increased group sex in qualitative but not quantitative data. Physical Closeness PrEP reduced psychological barriers to having sex (staying erect). Sexual Anxiety and Fears Better sex due to less anxiety Other No significant change in mean sexual satisfaction. |

| 16. Skinta et al. (2020) | San Francisco, CA; USA | Flyers, billboards in historically gay neighborhood, participant-driven recruitment February 2016 |

1. N=6 2. Mid 20's-late 30's 3. Men=100% 4. White=3; Latino=3 5. NR |

100% MSM/Gay | HIV-positive: 100% | Not on PrEP: 100% | Semi-structured interviews (Qualitative) | Desire for intimate connection Remembered experiences of stigma Men who do not take PrEP are suspect Awareness of the changing meaning of HIV |

Intimacy Greater experience of sexual intimacy. PrEP as a sign of commitment to a partner. Sexual Options More sexual openness. PrEP requirement for some when using dating applications. Easier for HIV-positive men to find partners. Other PrEP allowed greater agency over self-protection. |

1. N=# of participants; 2. Age range, Mean (standard deviation) if reported; 3. Gender; 4. Race/ethnicity; 5. Partnered status.

Same study sample as Gamarel & Golub (2019) Study 2

NR: Not Reported; MSM: men who have sex with men; IOS: inclusion of self in others; CAS: condomless anal sex; PLWH: people living with HIV

Results

Study Characteristics

Table 1 describes the study and participant characteristics, design, recurring themes regarding PrEP, and main findings. Two of the studies were exclusively quantitative; 10 studies were exclusively qualitative, involving interviews (7), focus groups (1), a combination (1), or text analysis (1); and four studies used mixed methods. Studies were conducted in eight countries: U.S., Canada, Eswatini, France, Uganda, England, Australia, and Belgium. The majority of studies elicited the experiences of gay or bisexual MSM (14), whereas two studies analyzed text or interviewed both men and women. There were 2,658 unique participants; 2,612 men (2 identified as transgender), 512 who were qualitatively assessed; 43 women, all qualitatively assessed; and 3 transgender women. Most of the studies had racially diverse participants (11); two studies only enrolled individuals identifying as Black, and three studies did not report racial or ethnic information. All 16 studies collected sexual orientation information and had a majority of gay or bisexual MSM participants. Five studies were conducted as part of larger PrEP demonstration projects. Seven studies examined only PrEP users, three studies examined only non-PrEP users, and the remainder (6) included a mix of PrEP adopters and non-PrEP adopters. Five studies specifically examined MSM in partnered relationships; however, only two studies (Malone et al., 2018; Nakku-Joloba et al., 2019), assessed both partners in a couple.

In the aggregate, both the quantitative and qualitative studies reviewed lend support for viewing the interaction between PrEP and sexual pleasure through two lenses: what PrEP has added to the sexual lives of persons on PrEP or can potentially add, and what PrEP has taken away. Using these lenses, several common themes emerged across the studies which we present in our results: PrEP as increasing intimacy, PrEP as increasing sexual options, PrEP as removing barriers to physical closeness, and PrEP as reducing sexual anxiety and fears.

PrEP as Increasing Intimacy

Studies involving primarily partnered individuals (Gamarel & Golub, 2015; Malone et al., 2018; Nakku-Joloba et al., 2019) as well as studies including MSM engaging in casual sexual encounters (Collins et al., 2017) found that desire for greater intimacy motivated willingness to adopt PrEP, distinct from simply removing a physical barrier (e.g., condom) to closeness. In Gamarel and Golub’s (2015) surveys of HIV-negative MSM in New York City in committed relationships, motivations to improve intimacy predicted PrEP adoption willingness. Indeed, the hypothesized association between the physical motivation for condomless sex and willingness to use PrEP was not supported in the Gamarel and Golub (2015) study. Notably, in a subsequent study, Gamarel and Golub (2019) found individuals who desired more closeness in their relationship were more likely to adopt PrEP. Intimacy motivations were also expressed by single men, with one participant commenting, “[I]t’s also just not having a condom on – it’s just so much more intimate that I’m actually giving my body to somebody and letting them cum inside me” (Collins et al., 2017, p. 59).

PrEP as Increasing Sexual Options

Many participants referred to PrEP as sexually liberating, allowing a broader possibility of sexual partners, including HIV positive persons (Collins et al., 2017; Quinn et al., 2020), alleviating fear around receptive sexual positions (Hughes et al., 2018; Mabire et al., 2019; Reyniers et al., 2020), and expanding the range of sexual activities that can be engaged in at clubs and parties (Grace et al., 2018; Harrington et al., 2020). As one MSM participant reflected, “Sex isn’t meant to be something you’re ashamed or fearful of…now that I can have bareback sex again, it’s just fantastic. Sex has been liberating again thanks to PrEP” (Grace et al., 2018, p. 26). Another Black MSM spoke of his new sexual freedom on PrEP as a “get out of jail free card” making him feel sexier as a partner (Quinn et al., 2020, p. 1382). Akin to liberation is the sexual empowerment expressed by MSM on PrEP, allowing individuals to define their own levels of acceptable risk and to responsibly practice safety in the context of sexual behaviors (DaSilva-Brandao & Iannni, 2020; Hughes et al., 2018; Malone et al., 2018; Philpot et al., 2020; Skinta et al., 2020).

PrEP as Removing Barriers to Physical Closeness

Sexual pleasure can be separated into physical pleasure and emotional intimacy. Likewise, sexual satisfaction goals include satisfying both physical and emotional needs and desires (Gamarel & Golub, 2020). Condom use is still often recommended for people using PrEP, as it does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, condoms may not always be utilized as for many, HIV prevention is the primary concern, particularly for HIV serodiscordant couples in committed monogamous relationships. In the literal sense, by eliminating the necessity to use condoms to protect against HIV transmission, PrEP removes a physical barrier to sexual pleasure, thereby increasing physical sexual satisfaction (Mabire et al., 2019). Condoms are experienced as “totally different from skin,” skin being preferred (p. 6). Men also discussed the awkwardness of condoms; including putting them on, maintaining an erection, and worry over whether a condom stayed on and intact during sexual intercourse. Several remarked how PrEP removed these negative thoughts when engaging in sexual activities. Couples in committed relationships referred to PrEP as allowing them to return to “live sex”, despite being in a serodiscordant relationship (Nakku-Joloba et al., 2019). Comments culled from a Facebook discussion group of gay and bisexual MSM reflected that sex on PrEP was seen as more natural, providing deeper sensation than sex with condoms (DaSilva-Brandao & Iannni, 2020). In one study, PrEP adoption was associated with higher sexual satisfaction scores for MSM in relationships (Gamarel & Golub, 2020).

PrEP as Reducing Sexual Anxiety and Fears

Hand in hand with sexual satisfaction, reducing sexual anxiety and fear was expressed by many participants as a motivation for PrEP use, as a specter of HIV risk hovered over many sexual encounters, inhibiting the sexual experience (Collins et al., 2017; Harrington et al., 2020; Hughes et al., 2018; Philpot et al., 2020; Quinn et al., 2020). In a longitudinal study of gay and bisexual MSM (Whitfield et al., 2019), PrEP status significantly predicted lower sexual anxiety compared to periods when not on PrEP. Although this study did not find PrEP status predicted sexual satisfaction, PrEP’s role in relieving the psychological barriers to sexual pleasure cannot be underestimated, as it threaded through most of the studies and reflections of PrEP users. As one MSM said, “You know, sexuality is your core, and it only makes sense that when that’s freer – I kind of refer to it as a second coming out” (Collins et al., 2017, p. 60). An older gay man reflected, “Who wants to be intimate with somebody and be in a state of terror? You know? You’re not giving your all” (Hughes et al., 2018, p. 394). For heterosexual couples, PrEP reduced fear in their relationships, making sexual intercourse less fraught with risk for the couple and opening the door to having children (Nakku-Joloba et al., 2019). In short, PrEP can transform “sex=risk” to “sex=pleasure” (DaSilva-Brandao & Iannni, 2020).

Discussion

Our systematic review of 16 studies examining PrEP use and sexual pleasure found that among MSM, PrEP use increased intimacy and options for sexual partners, sexual positions, and sexual activities; and reduced barriers to physical closeness, and anxiety and fears surrounding HIV transmission during intercourse. In HIV prevention, PrEP’s role in improving sexual health has been to reduce risk of HIV transmission; however, sexual health is much more than protecting against risk. Gamarel and Golub (2020) suggested that intimacy goals and sexual health goals are often intertwined, as connection achieved through sexual experience while on PrEP can enhance the relationship. These findings are in line with WHO’s current working definition of sexual health as encompassing “the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences,” (WHO, 2002; emphasis added) and WAS’s recognition that sexual pleasure is integral to sexual health, holistic health, and overall well-being (WAS, 2019). A recent essay published in The Lancet (Mitchell et al., 2021) has echoed these sentiments, calling sexual pleasure “distinctly relevant” to public health as it impacts diverse physical, psychological, and cultural outcomes. The reviewed studies reveal that MSM and other PrEP users experience their sexuality holistically as well, expressing the sexual freedom afforded by PrEP, whether by increasing intimacy or sexual diversity, reducing barriers to physical closeness, or reducing anxiety. PrEP messages to encourage uptake and adherence should consider these findings.

One theme in many of the reviewed studies was the control that PrEP affords over pleasure, and not solely over risk, whether framed as increasing options or reducing HIV anxiety. The synthesized findings in this review are consistent with studies finding that the use of PrEP was associated with reduced anxiety in MSM (Keen et al., 2020). As Race (2016) remarked, HIV prevention efforts have failed to acknowledge that sexual activities are intended to be pleasurable, targeting sexual risk behaviors as if sex is merely an activity like climbing, and evaluated based on risk rather than sexual connection between human beings with needs and desires. Defining sexual behaviors between MSM using terms such as sexual risk ignores the right to sexual pleasure, the desire for which was evident in the reviewed studies (Granta & Koesterb, 2016; Snowden et al., 2016). This right to sexual pleasure goes hand in hand with a right to sexual intimacy, as many participants in MSM relationships valued connection and closeness at least as much as physical pleasure.

A pertinent clarification emerging from the data was the extent to which PrEP has opened the door to risk compensation and whether the potential of risk compensation behaviors would offset gains to PrEP uptake through promoting sexual pleasure. Before PrEP and other recent biomedical advances, condoms were the most effective means of preventing HIV transmission during intercourse, and are still the most effective means of STI prevention. However, consistent with our results, research has found decreases in condom use as many feel that condoms act as a physical barrier to closeness with their sexual partners (Paz-Bailey et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2015) diminishing feelings of intimacy and pleasure (Fennell, 2014; Mabire et al., 2019), despite recent advances in condom technology creating more pleasurable condom designs. Although MSM reported associating PrEP with a desire for condomless anal sex (CAS), these statements were often made against the backdrop of persons acknowledging inconsistent condom use, viewing PrEP as making CAS less risky and not necessarily increasing the occurrence of CAS when on PrEP (Collins et al., 2017; Hughes et al., 2018). For many persons, although condom use behaviors changed to some degree, PrEP was not seen as a means to eliminate condoms entirely (Harrington et al., 2020). Other PrEP users stated that for them “HIV is the only significant STI”, and that they evaluated the risk of CAS as acceptable in certain situations, since “funerals are not held for chlamydia” (DaSilva-Brandao & Iannni, 2020, p. 1408). For many PrEP users, the decision to engage in CAS was a reflection of their individual risk perception toward other STIs, seen as extremely prevalent while at the same time easily treatable (Reyniers et al., 2020). Although engaging in CAS or more “adventurous” sexual behaviors while on PrEP may increase risk of STIs, the greater perception of sexual pleasure without condoms is a substantial motivator for PrEP adoption and thus may increase uptake and adherence (Prestage et al., 2019). In addition, open sexual agreements allowing casual sex with outside partners can increase HIV risk for the partnered couple, potentially negatively impacting trust and intimacy. Although negotiated safety agreements have been found to be effective for some partnered MSM (Jin et al., 2009), for those not diligently practicing HIV prevention techniques such as negotiated safety, U=U, or TasP, this risk can be obviated when PrEP is adopted, as PrEP mitigates risk when an agreement is broken or a “slip up” happens (Malone et al., 2018).

Pleasure-focused PrEP messaging could improve the sex lives of MSM by blunting the stigma around the sexual behaviors of sexual minorities (Grace et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019). Although not the focus of this review, HIV and PrEP stigma were referenced in many of the studies, notably in the qualitative responses of MSM (Collins, 2017; Philpott, 2020; Quinn et al., 2020). Openly promoting PrEP as enhancing sexual pleasure and positively depicting sex among MSM could chip away at the social norms that sanction only heterosexual sex or sex with condoms, which negatively stereotypes casual sex, club sex, and barebacking (Dubov et al., 2018; Knight et al., 2016; Marcus & Gillis, 2017; Schnarrs et al., 2018). In short, shifting the language surrounding PrEP from risk to pleasure has the potential to erase the line between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” consensual sex, reduce the negativity surrounding promiscuity, and stamp all sex - whether casual or committed - as equally safe (Auerbach & Hoppe, 2015; Marcus & Snowden, 2020). While framing safe sex using a pleasure-focused lens is not new, as evidenced by Knerr and Philpott’s work on the Pleasure Project (2006, 2009), PrEP’s effectiveness provides a unique opportunity to simultaneously reduce HIV risk and increase pleasure.

This review systematically examined the relationship between PrEP and pleasure, including both quantitative and qualitative studies, enabling a richer understanding of personal experiences and perceptions which provides support for novel ideas for effective messaging to increase PrEP uptake among sexual minorities. Notably, one limitation of this review was the small number of included studies that directly examined sexual satisfaction, sexual quality, or sexual pleasure. However, in several of the reviewed studies, themes of sexual pleasure were included among many topics discussed by participants. Moreover, while the results of this review can be generalizable to a wide variety of individuals who are on or interested in PrEP, it’s results may not be applicable to individuals who use other effective HIV prevention methods, including negotiated safety, U=U, or TasP. We chose to focus exclusively on PrEP for this review as each of the other strategies have their own limitations, often requiring negotiation or trusted open communication with sexual partners, whereas PrEP allows individuals to protect themselves from HIV whether partnered or engaging in casual sex. Included studies in this review examining PrEP and intimacy involved individuals who were not in relationships, thus considering intimacy outside of partnered or committed relationships.

Several studies outside of the time parameters of this review have recently been published that confirm that sexual satisfaction and sexual pleasure messaging could provide an effective avenue for increasing PrEP uptake and adherence. In their large online survey of 7,639 sexually active respondents, Marcus et al. (2021) found that PrEP users reported higher sexual satisfaction generally, with higher scores on specific components such as sexual sensations, sexual presence, and sexual variety. In their clinic-based study of PrEP users in Providence and Boston, Montgomery et al. (2021) found that sexual satisfaction scores significantly increased for MSM after PrEP uptake. In a focus group study conducted in France by Puppo et al. (2020), all 38 participants expressed increased sexual quality after being on PrEP. Zimmerman et al.’s (2021) interviews of 64 participants who were part of the larger AMPrEP demonstration project similarly found that PrEP users experienced more sexual diversity and sexual quality, although some persons reported increased preoccupation with sex and drug use. The psychological benefits of improved sexual quality and sexual expression after PrEP uptake was found by Van Dijk et al. (2021) in their survey of PrEP users in the Netherlands.

Further, while several authors have discussed incorporating sexual pleasure in HIV prevention messaging, the effectiveness of this messaging has yet to be tested beyond the #PrEP4Love campaign targeted at a younger population (Dehlin et al., 2019; Keene et al., 2020). Pleasure-oriented messaging should target middle and older adults, as contrary to social presumptions of asexuality, these populations remain sexually active well into late adulthood (Sinkovic & Towler, 2019). In addition, more studies should interview all partners in relationships; whether in dyads, triads, or other configurations, to better understand receptivity to overt pleasure messaging in terms of physical sensation, intimacy, sexual exploration, and reduced sexual anxiety. Finally, a systematic review studying the barriers and facilitators of PrEP among MSM conducted by Hannaford et al. (2017) included search terms such as stigma, social stigma, and awareness and attitudes, but not sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction or sexual quality, thus making this work a unique contribution to the field.

In conclusion, the present review adds to the understanding of a potential facilitator of PrEP uptake: sexual pleasure. Advocating for sexual pleasure in the lives of persons at risk for HIV may require the re-education of health care professionals, whose stigmatized views toward PrEP and PrEP users have also been cited as barriers to PrEP access and uptake (Calabrese et al., 2019; Devarajan et al., 2020). The results from this review suggest that future research should explore receptiveness toward explicit pleasure-based messages within sexual minorities, single MSM, couples, other relationship dynamics, and health care professionals. It is high time for HIV researchers to frame sex, sexual satisfaction, and sexual pleasure as valid objectives for persons of all sexual orientations and identities.

Acknowledgements:

The authors have no acknowledgements to mention.

The first two authors should be considered co-authors on this manuscript.

Source of Funding:

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health under grant T32MH074387-15

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Auerbach JD, & Hoppe TA (2015). Beyond “getting drugs into bodies”: Social science perspectives on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18, n/a-n/a. 10.7448/IAS.18.4.19983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bärnighausen KE, Matse S, Kennedy CE, Lejeune CL, Hughey AB, Hettema A, Bärnighausen TW, & McMahon SA (2019). “This is mine, this is for me”: Preexposure prophylaxis as a source of resilience among women in Eswatini. AIDS, 33, S45–S52. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone CA, & Bowleg L (2020). Structuring sexual pleasure: Equitable access to biomedical HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 157–159. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosh KA, Johnson AS, Hernandez AL, Prejean J, Taylor J, Wingard R, Valleroy LA, Hall HI (2020). Vital signs, deaths among persons with diagnosed HIV infection, United States, 2010–2018. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, [s. l.], v. 69 (, n. 46), p. 1617–1724. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Tekeste M, Mayer KH, Magnus M, Krakower DS, Kershaw TS, Eldahan AI, Gaston Hawkins LA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Betancourt JR, & Dovidio JF (2019). Considering stigma in the provision of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Reflections from current prescribers. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 33(2), 79–88. 10.1089/apc.2018.0166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, & Underhill K (2015). How stigma surrounding the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis undermines prevention and pleasure: A call to destigmatize “Truvada Whores.’ American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 1960–1964. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda D (Ed.). (2013). The essential handbook of women’s sexuality. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). HIV Surveillance Report. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018) HIV Surveillance Report, https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf (Retrieved September 5, 2021)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/consumer-info-sheets/cdc-hiv-consumer-info-sheet-pep-101.pdf (Retrieved September 5, 2021)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/ (Retrieved August 6, 2021)

- Collins SP, McMahan VM, & Stekler JD (2017). The impact of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use on the sexual health of men who have sex with men: A qualitative study in Seattle, WA. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29(1), 55–68. 10.1080/19317611.2016.1206051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva-Brandeo RR, & Ianni AMZ (2020). Sexual desire and pleasure in the context of the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Sexualities, 23(8), 1400–1416. 10.1177/1363460720939047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darbes LA, Chakravarty D, Neilands TB, Beougher SC, & Hoff CC (2014). Sexual risk for HIV among gay male couples: A longitudinal study of the impact of relationship dynamics. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(1), 47–60. 10.1007/s10508-013-0206-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlin JM, Stillwagon R, Pickett J, Keene L, & Schneider JA (2019). #PrEP4Love: An evaluation of a sex-positive HIV prevention campaign. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(2), e12822. 10.2196/12822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan S, Sales JM, Hunt M, & Comeau DL (2020). PrEP and sexual well-being: A qualitative study on PrEP, sexuality of MSM, and patient-provider relationships. AIDS Care, 32(3), 386–393. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1695734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, & Huebner DM (2012). Is good sex good for you? Rethinking sexuality and health. Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 6(1), 54–69. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00408.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubov A, Galbo P Jr, Altice FL, & Fraenkel L (2018). Stigma and shame experiences by MSM who take PrEP for HIV prevention: A qualitative study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1843–1854. 10.1177/1557988318797437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, & Maksut J (2017). Stigma and conspiracy beliefs related to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and interest in using PrEP among Black and White men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1236–1246. 10.1007/s10461-017-1690-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell J (2014). “And isn’t that the point?”: Pleasure and contraceptive decisions. Contraception, 89(4), 264–270. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JV, Corona Vargas E, Finotelli I Jr., Fortenberry JD, Kismödi E, Philpott A, Rubio-Aurioles E, & Coleman E (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn KE, Lin L, Bruner DW, Cyranowski JM, Hahn EA, Jeffery DD, Reese JB, Reeve BB, Shelby RA, & Weinfurt KP (2016). Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to quality of life throughout the life course of U.S. adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(11), 1642–1650. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, & Golub SA (2015). Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(2), 177–186. 10.1007/s12160-014-9646-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, & Golub SA (2019). Closeness discrepancies and intimacy interference: Motivations for HIV prevention behavior in primary romantic relationships. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(2), 270–283. 10.1177/0146167218783196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, & Golub SA (2020). Sexual goals and perceptions of goal congruence in individuals’ PrEP adoption decisions: A mixed-methods study of gay and bisexual men who are in primary relationships. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 54(4), 237–248. 10.1093/abm/kaz043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel K, Starks T, Dilworth S, Neilands T, Taylor J, & Johnson M (2014). Personal or relational? Examining sexual health in the context of HIV serodiscordant same-sex male couples. AIDS & Behavior, 18(1), 171–179. 10.1007/s10461-013-0490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard G, Patten S, LeBlanc M, Adam BD, & Jackson E (2019). Is HIV prevention creating new biosocialities among gay men? Treatment as prevention and pre-exposure prophylaxis in Canada. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(3), 484–501. 10.1111/1467-9566.12826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub S, Starks T, Payton G, & Parsons J (2012). The critical role of intimacy in the sexual risk behaviors of gay and bisexual men. AIDS & Behavior, 16(3), 626–632. 10.1007/s10461-011-9972-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace D, Jollmore J, MacPherson P, Strang MJP, & Tan DHS (2018). The pre-exposure prophylaxis-stigma paradox: Learning from the first wave of PrEP users. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(1), 24–30, 10.1089/apc.2017.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granta RM, & Koesterb KA (2016). What people want from sex and preexposure prophylaxis. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 11(1), 3 10.1097/COH.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S & Kismodi E (2020). A call for (renewed) commitment to sexual health, sexual rights, and sexual pleasure: A matter of health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (2), 159–160. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyonvarch O, Vaillant L, Hanslik T, Blanchon T, Rouveix E, & Supervie V (2021). Prévenir le VIH par la PrEP: Enjeux et perspectives [HIV prevention with PrEP: Challenges and prospects]. La Revue de Medecine Interne, 42(4), 275–280. 10.1016/j.revmed.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford A, Lipshie-Williams M, Starrels JL, Arnsten JH, Rizzuto J, Cohen P, Jacobs D, & Patel VV (2018). The use of online posts to identify barriers to and facilitators of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: A comparison to a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. AIDS & Behavior, 22(4), 1080–1095. 10.1007/s10461-017-2011-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington S, Grundy-Bowers D, & McKeown DE (2020). “Get up, brush teeth, take PrEP”: A qualitative study of the experiences of London-based MSM using PrEP. HIV Nursing, 20(3), 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hojilla JC, Koester K, Cohen S, Buchbinder S, Ladzekpo D, Matheson T, & Liu A (2016). Sexual behavior, risk compensation, and HIV prevention strategies among participants in the San Francisco PrEP Demonstration Project: A qualitative analysis of counseling notes. AIDS & Behavior, 20(7), 1461–1469. 10.1007/s10461-015-1055-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt M, Lea T, Murphy D, de Wit J, Bear B, Halliday D, Ellard J, & Kolstee J (2019). Trends in attitudes to and the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by Australian gay and bisexual men, 2011–2017: Implications for further implementation from a diffusion of innovations perspective. AIDS & Behavior, 23(7), 1939–1950. 10.1007/s10461-018-2368-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais O, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau MC, & Vedel I (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SD, Sheon N, Andrew EVW, Cohen SE, Doblecki-Lewis S, & Liu AY (2018). Body/selves and beyond: Men’s narratives of sexual behavior on PrEP. Medical Anthropology, 37(5), 387–400. 10.1080/01459740.2017.1416608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage G, Zablotska I, Imrie J, Kippax S, Kaldor J & Grulich A (2009). Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS, 23 (2), 243–252. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S (2013). HIV treatments as prevention (TasP): Primer for behavior-based implementation. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Keen P, Hammoud MA, Bourne A, Bavinton BR, Holt M, Vaccher S, Haire B, Saxton P, Jin F, Maher L, Grulich AE & Prestage G (2020). Use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) associated with lower HIV anxiety among gay and bisexual men in Australia who are at high risk of HIV infection: Results From the Flux Study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 83(2), 119–125. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene LC, Dehlin JM, Pickett J, Berringer KR, Little I, Tsang A, Bouris AM, & Schneider JA (2020). #PrEP4Love: Success and stigma following release of the first sex-positive PrEP public health campaign. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(3), 1–17. 10.1080/13691058.2020.1715482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Crawford J, Davis M, Rodden P, & Dowsett G (1993). Sustaining safe sex: A longitudinal study of a sample of homosexual men. AIDS, 7(2), 257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S & Holt M (2016). Diversification of risk reduction strategies and reduced threat of HIV may explain increases in condomless sex. AIDS, 30(18), 2898–2899. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Noble J, Prestage G, Crawford JM, Campbell D, Baxter D, & Cooper D (1997). Sexual negotiation in the AIDS era: negotiated safety revisited. AIDS, 11(2), 191–197. 10.1097/00002030-199702000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr W, & Philpott A (2009). Promoting safer sex through pleasure: Lessons from 15 countries. Development, 52(1), 95–100. 10.1057/dev.2008.79 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr W, & Philpott A (2006). Putting the sexy back into safer sex: The pleasure project. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/8364/IDSB_37_5_10.1111-j.1759-5436.2006.tb00310.x.pdf?sequence=1

- Knight R, Small W, Carson A, & Shoveller J (2016). Complex and conflicting social norms: Implications for implementation of future HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) interventions in Vancouver, Canada. PloS One, 11(1), e0146513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester K, Amico RK, Gilmore H, Liu A, McMahan V, Mayer K, Hosek S, & Grant R (2017). Risk, safety and sex among male PrEP users: Time for a new understanding. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 19(12), 1301–1313. 10.1080/13691058.2017.1310927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers S, & Kapadia F (2020). The public health of pleasure: Going beyond disease prevention. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 140–141. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Glasser DB, Kang J, Wang T, Levinson B, Moreira ED Jr., Nicolosi A, & Gingell C (2006). A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: Findings from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(2), 145–161. 10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance K & Byers ES (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships 2, 267–285. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc NM, Mitchell JW, & De Santis JP (2017). Negotiated safety-components, context and use: An integrative literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1583–1603. 10.1111/jan.13228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabire X, Puppo C, Morel S, Mora M, Rojas Castro D, Chas J, Cua E, Pintado C, Suzan-Monti M, Spire B, Molina J, & Préau M (2019). Pleasure and PrEP: Pleasure-seeking plays a role in prevention choices and could lead to PrEP initiation. American Journal of Men’s Health, 13(1). 10.1177/1557988319827396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone J, Syvertsen JL, Johnson BE, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, & Bazzi AR (2018). Negotiating sexual safety in the era of biomedical HIV prevention: Relationship dynamics among male couples using pre-exposure prophylaxis. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(6), 658–672. 10.1080/13691058.2017.1368711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JL, Glidden DV, Mayer KH, Liu AY, Buchbinder SP, Amico KR, McMahan V, Kallas EG, Montoya-Herrera O, Pilotto J, & Grant RM (2013). No evidence of sexual risk compensation in the iPrEx trial of daily oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Plos One, 8(12), 1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus J, Sewell W, Powell V, Ochoa A, Mayer K & Krakower D (2021). HIV preexposure prophylaxis and sexual satisfaction among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=ovftw&NEWS=N&AN=00007435-900000000-97736. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JL, & Snowden JM (2020). Words matter: Putting an end to “unsafe” and “risky” sex. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 47(1), 1–3. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus N, & Gillis JR (2017). Increasing intimacy and pleasure while reducing risk: Reasons for barebacking in a sample of Canadian and American gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Sexualities Review, 8(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Agwu A, & Malebranche D (2020). Barriers to the wider use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: A narrative review. Advances in Therapy, 37(5), 1778–1811. 10.1007/s12325-020-01295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KR, Lewis R, O’Sullivan LF & Fortenberry D (2021). What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health? The Lancet, 6(8), E608–E613 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(21)00099-2/fulltext [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of International Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, Pialoux G, Cotte L, Charreau I, Tremblay C, Le Gall JM, Cua E, Pasquet A, Raffi F, Pintado C, Chidiac C, Chas J, Charbonneau P, Delaugerre C, Suzan-Monti M, Loze B, Fonsart J, &, ANRS IPERGAY Study Group. (2015). On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(23), 2237–2246. 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño MA, Dombrowski JC, Dasgupta S, Golden MR, Duerr A, Manhart LE, Barbee LA, & Khosropour CM (2019). Changes in sexual behavior and STI diagnoses among MSM initiating PrEP in a clinic setting. AIDS & Behavior, 23(2), 548–555. 10.1007/s10461-018-2252-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MC, Ellison J, Chan PA, Harrison L, & van den Berg JJ (2021). Sexual satisfaction with daily oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among gay and bisexual men at two urban PrEP clinics in the United States: An observational study. Sexual Health. 2021 Aug 27. 10.1071/SH20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakku-Joloba E, Pisarski EE, Wyatt MA, Muwonge TR, Asiimwe S, Celum CL, Baeten JM, Katabira ET, & Ware NC (2019). Beyond HIV prevention: Everyday life priorities and demand for PrEP among Ugandan HIV serodiscordant couples. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(1), 1–8. 10.1002/jia2.25225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Times (2020). H.I.V. Death rates fell by half, C.D.C. says. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/19/health/hiv-aids-death-rates-cdc.html?campaign_id=9&emc=edit_nn_20201120&instance_id=24296&nl=the-morning®i_id=131182241&segment_id=45029&te=1&user_id=e9dacb3cc0677167942667cd3427b1d6 Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- Newcomb ME, Moran K, Feinstein BA, Forscher E, & Mustanski B (2018). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use and condomless anal sex: Evidence of risk compensation in a cohort of young men who have sex with men. JAIDS: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 77(4), 358–364. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg CE, Nunn AS, Montgomery M, Almonte A, Mena L, Patel RR, Mayer KH & Chan PA (2018). Behavioral changes following uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in a clinical setting. AIDS and Behavior, 22(4), 1075–1079. 10.1007/s10461-017-1701-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, ... & US Preventive Services Task Force. (2019). Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 321(22), 2203–2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Bailey G, Mendoza MC, Finlayson T, Wejnert C, Le B, Rose C, Raymond HF, Prejean J, & NHBS Study Group (2016). Trends in condom use among MSM in the United States: The role of antiretroviral therapy and seroadaptive strategies. AIDS, 30(12), 1985–1990. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng P, Su S, Fairley CK, Chu M, Jiang S, Zhuang X, & Zhang L (2018). A global estimate of the acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS & Behavior, 22(4), 1063–1074. 10.1007/s10461-017-1675-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpot S, Prestage G, Holt M, Haire B, Maher L, Hammoud M, & Bourne A (2020). Gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a context of high accessibility: An Australian qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior, 10.1007/s10461-020-02796-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RA & Greene RE (2020). Promoting positive sexual health. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (2), 159–160. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestage G, Maher L, Grulich A, Bourne A, Hammoud M, Vaccher S, Bavinton B, Holt M & Jin F (2019). Brief report: Changes in behavior after PrEP initiation among Australian gay and bisexual men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 81 (1), 52–56. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppo C, Préau M, Bonnet B, Bernaud C, Malet M, Henry C, Gorre R, Lanier S, Coutherut J, & Biron C (2020). Étude qualitative par focus groups de la qualité de vie sexuelle et la satisfaction des personnes suivies pour PrEP. Medecine & Maladies Infectieuses, 50(6), S188. 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.06.402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Mizuno Y, Smith DK, Grabbe K, Courtenay-Quick C, Tomlinson H, & Mermin J (2014). Incorporating couples-based approaches into HIV prevention for gay and bisexual men: Opportunities and challenges. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(1), 35–46. 10.1007/s10508-013-0205-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn KG, Christenson E, Sawkin MT, Hacker E, & Walsh JL (2020). The unanticipated benefits of PrEP for young black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 24(5), 1376–1388. 10.1007/s10461-019-02747-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn KG, Zarwell M, John SA, Christenson E, & Walsh JL (2020). Perceptions of PrEP use within primary relationships among young Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(6), 2117–2128. 10.1007/s10508-020-01683-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race K (2016). Reluctant objects. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian & Gay Studies, 22(1), 1–31. 10.1215/10642684-3315217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit YS, Dubov A, Polonsky M, Fraenkel L Rich KM, Ogunbajo A & Altice FL (2020). Dual motivational model of pre-exposure prophylaxis use intention: Model testing among men who have sex in Ukraine. AIDS Care, 32(2), 361–266. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1640845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Cienfuegos-Szalay J, Talan A, Jones SS, & Jimenez RH (2020). Growing acceptability of Undetectable = Untransmittable but widespread misunderstanding of transmission risk: Findings from a very large sample of sexual minority men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 83(3): 215–22. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyniers T, Nöstlinger C, Vuylsteke B, De Baetselier I, Wouters K, & Laga M (2020). The impact of PrEP on the sex lives of MSM at high risk for HIV infection: Results of a Belgian cohort. AIDS and Behavior, 10.1007/s10461-020-03010-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, & Bachmann G (2008). Sexual well-being, happiness, and satisfaction in women: The case for a new conceptual paradigm. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 34(4), 291–297. 10.1080/00926230802096234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher D (2013). Addressing sexual health: Looking back, looking forward. Public Health Reports, 23, Supplement 1, 111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer R, Schmidt HA, Ravasi G, Mozalevskis A, Rewari BB, Lule F, Yeboue K, Brink A, Mangadan Konath N, Sharma M, Seguy N, Hermez J, Alaama AS, Ishikawa N, Dongmo Nguimfack B, Low-Beer D, Baggaley R, & Dalal S (2021). Adoption of guidelines on and use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis: A global summary and forecasting study. The Lancet HIV, 8(8), e502–e510. 10.1016/s2352-3018(21)00127-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnarrs PW, Martin-Valenzuela R, Delgado AJ, McAdams J, Gordon D, Sunil T, Glidden D, & Parsons JT (2018). Perceived social norms about oral PrEP use: Differences between African-American, Latino and White gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Texas. AIDS & Behavior, 22(11), 3588–3602. 10.1007/s10461-018-2076-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidebottom D, Ekstrom AM & Stromdahl S (2018). A systematic review of adherence to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV – how can we improve uptake and adherence? BMC Infectious Diseases 18(1), 581. 10.1186/s12879-018-3463-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinković M, & Towler L (2019). Sexual aging: A systematic review of qualitative research on the sexuality and sexual health of older adults. Qualitative Health Research, 29(9), 1239–1254. 10.1177/1049732318819834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinta MD, Brandrett BD, & Margolis E (2020). Desiring intimacy and building community: Young, gay and living with HIV in the time of PrEP. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 1–13. 10.1080/13691058.2020.1795722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Herbst JH, Zhang X, & Rose CE (2015). Condom effectiveness for HIV prevention by consistency of use among men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 68(3), 337–344. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden JM, Rodriguez MI, Jackson SD, & Marcus JL (2016). Pre-exposure prophylaxis and patient centeredness: A call for holistically protecting and promoting the health of gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 10(5), 353–358. 10.1177/1557988316658288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson KR, & Meston CM (2015). The conditional importance of sex: Exploring the association between sexual well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(1), 25–38. 10.1080/0092623X.2013.811450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, & Siegler AJ (2018). Getting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to the people: Opportunities, challenges and emerging models of PrEP implementation. Sexual Health, 15(6), 522–527. 10.1071/SH18103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CJ, Anderson KM, Toevs K, Morrison D, Wells C, & Nicolaidis C (2019). “Little tablets of gold”: An examination of the psychological and social dimensions of PrEP among LGBTQ communities. AIDS Education and Prevention, 31(1), 51–62. 10.1521/aeap.2019.31.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut JW, & Kelley HH (1959). The social psychology of groups (pp. 9–30). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Fact Sheet (2021). https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf (Retrieved September 1, 2021)

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019). FDA approves second drug to prevent HIV infection as part of ongoing efforts to end the HIV epidemic. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-drug-prevent-hiv-infection-part-ongoing-efforts-end-hiv-epidemic. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2020). Truvada for PrEP fact sheet. https://www.fda.gov/media/83586/download. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- Van Dijk M, De Wit JBF, Guadamuz TE, Martinez JE, & Jonas JK (2021) Quality of sex life and perceived sexual pleasure of PrEP users in the Netherlands. Journal of Sex Research, DOI: 10.1080/00224499.2021.1931653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, Blechinger D, Nguyen DP Follansbee S, & Hare CB (2015). No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 61(10), 1601–1603, doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield THF, Jones SS, Wachman M, Grov C, Parsons JT, & Rendina HJ (2019). The impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use on sexual anxiety, satisfaction, and esteem among gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sex Research, 56(9), 1128–1135. 10.1080/00224499.2019.1572064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Association for Sexual Health. (2019). Mexico City World Congress of Sexual Health: Declaration on sexual pleasure. https://worldsexualhealth.net/declaration-on-sexual-pleasure/