Abstract

Sleep-disordered breathing reflects a continuum of overnight breathing difficulties, ranging from mild snoring to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep-disordered breathing in childhood is associated with significant adverse outcomes in multiple domains of functioning. This review summarizes the evidence of well-described ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic disparities in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing, from its prevalence to its treatment-related outcomes. Research on potential socio-ecological contributors to these disparities is also reviewed. Critical future research directions include the development of interventions that address the modifiable social and environmental determinants of these health disparities.

Keywords: Sleep-disordered breathing, health disparities, race, environment

1.1. Sleep-disordered breathing definition, diagnosis, and sequalae

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) reflects a continuum of overnight breathing difficulties, ranging from mild snoring to its most severe form, the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).1–3 SDB is characterized by respiratory symptoms, such as snoring, gasping, and pauses in breathing, that disrupt sleep architecture.4,5 Polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard for diagnosing pediatric SDB severity,5 although some caregiver-completed questionnaires show strong sensitivity and specificity in detecting clinically significant OSAS.6,7

Regardless of its severity, untreated pediatric SDB is associated with significant adverse outcomes in multiple domains of functioning. Snoring and OSAS have each been associated with obesity, hypertension,8–10 and poor asthma control.11 Across the continuum of children with SDB, there is also evidence of marked deficits in neurobehavior, including impairments in attention, behavioral regulation, and broad executive functioning skills.12–14 Indeed, a recent study using brain imaging has shown that greater caregiver-reported child SDB symptoms are linked to thinner cortical gray matter in the frontal lobes, which impacts executive functioning skills.15 Untreated SDB is costly for patients and the healthcare system, as SDB can result in a 215% elevation in child healthcare usage and 40% more hospital visits.16 Specifically, children with OSAS additionally show a 7-fold increase in risk of death,17 underscoring the importance of early SDB identification and treatment.

1.2. Prevalence and disparities

SDB occurs in 10 to 17% of children,1–3,18 with 1 to 3% experiencing OSAS,19 making OSAS the second most common pediatric chronic health condition after asthma (8.6%).20 SDB is more prevalent among some pediatric populations. SDB risk is increased during early childhood, as adenotonsillar hypertrophy, which can cause obstructive events, peaks between 3 and 6 years of age.21,22 However, obesity is another factor that can increase SDB risk, with one study finding that SDB occurred in 13% of adolescents with obesity versus a prevalence of 2% in non-obese adolescents.23 OSAS is also estimated to occur in over 69% of youth with Down Syndrome, due to the impact of hypotonia and other craniofacial differences on upper airway patency.24

There are well-documented racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in pediatric SDB, from its prevalence to its treatment-related outcomes. Most of the available research on racial and ethnic disparities in SDB has compared non-Latinx Black/African American (hereafter, ‘Black’) youth to non-Latinx White (hereafter, ‘White’) youth.25 Research indicates that Black youth are 4-6 times more likely than their White counterparts to experience SDB, across severities.26,27 Black children also experience greater OSA severity (increased apnea hypopnea index) on PSG relative to White children, even when controlling for obesity and other OSA contributors, such as asthma and a history of prematurity.28,29 Adjusting for racial and ethnic differences, socioeconomic status (SES) is also independently associated with SDB, with children living in lower-SES homes or socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods being more likely to evidence SDB compared to their more socioeconomically advantaged peers.25,30,31

Among youth diagnosed with OSAS, Black children are also less likely than White children to receive adenotonillectomy,25,32,33 the first line treatment approach.28 In a large-scale study using state-level pediatric healthcare data, tonsillectomy among all youth, regardless of presenting diagnosis, was lower among Black as well as Hispanic/Latinx patients compared to White youth and among those who were publicly compared to privately insured.32 A smaller study of children diagnosed with SDB also found that publicly-insured youth experienced delays in related care, with longer intervals between the initial SDB diagnosis and subsequent polysomnogram or surgical treatment compared to privately insured children.34

Initial evidence also demonstrates disparities in the neurobehavioral symptoms of SDB and related treatment response. Neurobehavioral impairments and daytime sleepiness are key symptoms of pediatric SDB that may especially impact children, who have a plastic and rapidly developing nervous system.28,35 Although not designed to examine racial differences in OSAS, in the Childhood Adenotonsillectomy (CHAT) study, Black youth showed greater neurobehavioral impairments and daytime sleepiness at baseline compared to White youth and those of other racial and ethnic backgrounds.28 Of note, CHAT also demonstrated that adenotonsillectomy for OSAS reduced the obstructive apnea hypopnea index (OAHI) and child neurobehavioral concerns, however, these improvements were diminished in Black youth.28

1.3. Contributors to disparities in SDB and related outcomes

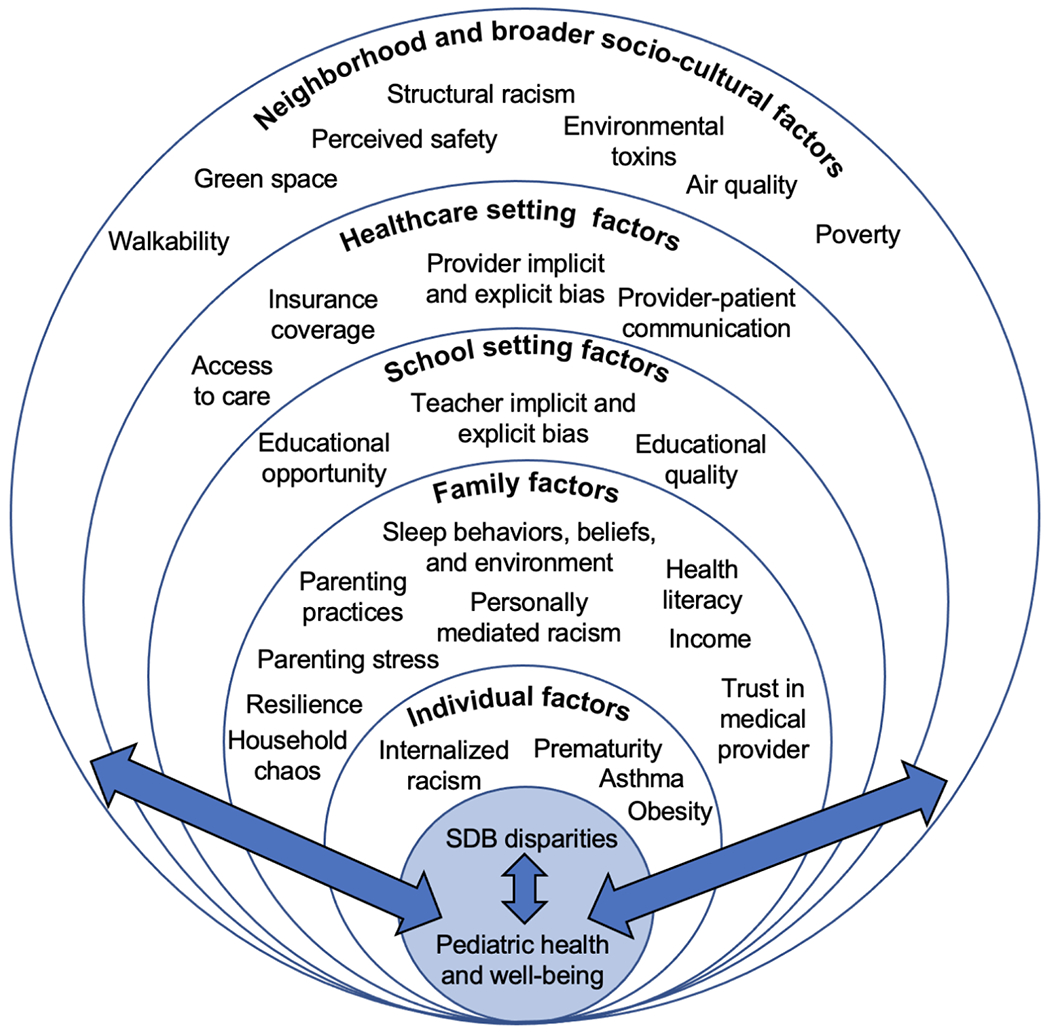

In identifying contributors to racial and ethnic health disparities, it is crucial to recognize that race and ethnicity are socio-political as opposed to a biological constructs, and that observed disparities are due to social and environmental factors.36,37 From a socio-ecological perspective,38 socio-political and neighborhood-level factors along with other child, family, school, and healthcare setting factors are determinants of disparities in SDB prevalence, treatment access, and SDB-related child outcomes. We have applied this socio-ecological perspective to sleep health disparities across the lifespan39 and with regard to pediatric sleep problems40 and treatments.41 In the sections that follow and in Figure 1, we summarize putative mechanisms of disparities in SDB and its outcomes. Of note, the factors summarized here do not represent an exhaustive list of potential determinants of these disparities, and future research is needed into factors at multiple levels that could be leveraged to inform SDB prevention and intervention.

Figure 1.

Socio-ecological model showing multi-level factors contributing to sleep health disparities (adapted from Billings et al.39 with permission).

Racism.

While racism and discrimination are understudied in the context of pediatric sleep and SDB in particular, racism and discrimination are undoubtedly root causes of disparities in SDB and its impact on child functioning.36 Racism is therefore a crosscutting theme in our socio-ecological model that impacts children at the level of the individual child, family, school, healthcare system, and neighborhood. This is because racism operates across multiple domains (i.e., systemic, institutional, and structural; personally-mediated; internalized)42–44 Structural racism refers to policies, laws, and regulations on a local, state, and national level that result in differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities based on race.43 For example, the legacy of redlining has lasting effects on residential segregation, impacting where children live.45,46 Increased exposure to allergens and toxins found in historically redlined neighborhoods may in turn increase upper airway inflammation and propensity for SDB.31

Next, personally-mediated racism exists in the form of discrimination, implicit bias, and explicit bias.42,47 Historical and ongoing personally-mediated racism faced by Black families is understudied in relation to pediatric sleep health disparities, despite multiple pathways linking racism to sleep and functional outcomes. Personally-mediated racism is associated with poorer caregiver mental health,44,48 which can in turn impact the caregiver-child relationship and child neurobehavioral and social-emotional skills.49,50 Caregivers’ own experiences of racism and discrimination have been directly linked their parenting practices,51 child mental health,52–54 caregiver’s own sleep,55 and their child’s sleep duration.56 Research has also linked child experiences of racism to worse child sleep, typically in older samples.57–60 A study of Black, Asian, and Latinx adolescents found that daily experiences of discrimination were linked to increased same-night sleep disturbances and greater next-day daytime sleepiness,60 although SDB was not assessed. More broadly, experiences of bias and discrimination are robustly linked to worse behavioral health (anxiety; emotional distress)61–63 and can trigger physiologic responses that increase risk for poor health outcomes,64–66 such as those related to SDB.

Child factors.

A crucial but largely overlooked factor that could account for some of the observed disparities in child SDB outcomes is broad sleep health, and particularly sleep duration. Similar to pediatric SDB, there are racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the proportion of youth obtaining insufficient sleep,67,68 or less total (24-hour) sleep than recommended according to age-based national (US) guidelines.69 Insufficient sleep is even more common than SDB, occurring in approximately 36% of preschoolers,40 50% of school-aged children,70 and over 70% of adolescents.71 In addition, like SDB, insufficient sleep is associated with impairments in attention, executive functioning, and other neurobehavioral outcomes,72,73 as well as increased risk of obesity and cardiometabolic concerns.74 Few studies have examined the overlap among SDB symptoms and insufficient sleep,75,76 and the potential synergistic effects of these co-occurring sleep problems on child neurobehavioral and physical health functioning.77 There is also a paucity of research on how other modifiable aspects of sleep health, including poor sleep health behaviors (e.g., inconsistent bedtime routines, evening electronics usage, caffeine consumption),78 may contribute to disparities in SDB-related outcomes.

Family factors.

Family beliefs and behaviors are crucial contributors to pediatric sleep health and development but are understudied in the context of SDB. Emerging qualitative research,79 for example, indicates that sleep health promotion for young children may need adaptation to address caregivers’ beliefs about optimal child sleep duration and evening electronics usage. Caregivers’ own sleep and the home sleep environment (light, noise) may also influence child sleep duration and other key sleep health behaviors linked to developmental outcomes among youth with SDB.80,81

Additional family factors, such as parenting style,82,83 child and caregiver exposure to stress and adverse childhood experiences,80,84,85 and household chaos86,87 have all been linked to both child sleep health and the neurobehavioral outcomes implicated in child SDB. Consistent with a socio-ecological framework, these factors likely accumulate and interact to influence child outcomes. For instance, lower family-level SES, typically indexed by family income and caregiver education or occupation, can exacerbate parenting stress, negatively impacting parenting practices and child wellbeing.46,88,89 Limited family resources (e.g., availability of an individual bed or room) may also impede sufficient and healthy childhood sleep.90 Lower caregiver health-related literacy has been linked to worse pediatric sleep habits91 and could impact sleep treatment-related behavior and decision-making, but has not been studied in relation to disparities in pediatric SDB. Thus, multiple family functioning and environmental factors are necessary to examine in relation to disparities in SDB-related neurobehavioral outcomes.

School factors.

In addition to family, teachers and the educational context contribute to broad child development and could theoretically contribute to disparities in SDB-related neurobehavioral and academic outcomes. Relevant to racial disparities, teachers are often included in research on the neurobehavioral impacts of SDB. However, the potential impact of teachers’ racial biases and stereotypes on their ratings of child behavior in SDB research is unknown. Research in other areas of child development demonstrates that teachers hold pro-White/anti-Black implicit racial biases.92,93 Implicit bias refers to attitudes toward a person, group, or idea that are unconscious but can influence behaviors. Accordingly, racial biases influence how teachers interpret students’ behaviors as well as their expectations of future student behavior.94,95 Biases and stereotypes may also explain racial disparities in suspensions and expulsions that occur as early as preschool and kindergarten.96 Compared to White youth, teachers perceive Black boys as having more dangerous misbehavior, Black girls as being naturally angrier, and Black youth overall as being angry more often.97,98 These disparities and their consequences can lead to poor educational outcomes and juvenile justice involvement.99–101 Students who experience bias and discrimination additionally have worse student-teacher relationships, school engagement, and academic motivation.102 Research that considers these school factors is necessary to better understand and intervene upon the causes of racial disparities in SDB outcomes.

Healthcare setting factors.

As described above, there are racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in SDB identification and treatment.25,103 However, salient healthcare setting factors are largely unexplored in pediatric SDB. For example, patient and family trust in the physician and the healthcare system have been associated with disparities in use of preventive services, medication adherence, and satisfaction with care.104–106 Mounting research indicates that healthcare providers also have implicit racial bias that may contribute to health disparities. van Ryn has proposed a theoretical model for mechanisms through which healthcare providers and implicit bias may contribute to these disparities.107 Within this model, it is hypothesized that patient race/ethnicity activates provider conscious (explicit) and unconscious (implicit) patient-related beliefs.108 A recent review of 37 studies on implicit bias in healthcare revealed that most healthcare providers, similar to the general US population, have implicit racial/ethnic biases that negatively impact patient-provider communication.109 It is further hypothesized that explicit and implicit provider beliefs influence symptoms interpretation;107 in the context of SDB, this could lead to delayed diagnosis or referrals for care. This hypothesis is supported by research among psychiatrists demonstrating that, compared to vignettes with White patients, otherwise identical cases with Black patients were regarded as more violent and criminal.110

Provider beliefs about patients also influence clinical decision making, as supported by studies linking implicit bias with disparities in treatment.111,112 Provider patient-related beliefs can additionally influence providers’ interpersonal behavior.107 For example, patient race has been found to influence physician nonverbal attention, empathy, courtesy and information giving.113 Higher provider implicit bias is also associated with poorer ratings of patient-provider communication.114–117 Provider interpersonal behaviors can influence patient (or caregiver) attitudes and behaviors during the visit, adherence to treatment recommendations after the visit, and satisfaction with care.107 Racially and ethnically minoritized patients have reported that medical staff treated them with disrespect based on race/ethnicity.118 Increased provider implicit bias is also linked to decreased patient confidence in treatment recommendations.117 It is possible that this lack of patient/family confidence in provider recommendations contributes to the documented racial disparities in OSA treatment via adenotonsillectomy.25,32 While this theoretical model and the associated supporting research provides a scientific premise for the ways in which healthcare providers contribute to disparities, to our knowledge no studies have examined these crucial factors in relation to pediatric SDB disparities.

Neighborhood factors.

Multiple aspects of the neighborhood context, including social (perceptions of safety) and physical characteristics (green space, walkability, air quality), have linked to child sleep outcomes, including SDB,119 although most pediatric SDB research has focused on neighborhood-level SES. In the CHAT study, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage partially accounted for OSA severity in Black children, beyond family income and education.30 Residing in a disadvantaged neighborhood context may confer risk for heightened exposure to environmental toxins and allergens, which as noted above could contribute to increased SDB symptoms via upper airway inflammation.30,31 At the same time, toxins such as lead in poor-quality housing or secondhand smoke exposure are especially deleterious for the developing brain, resulting in significant neurobehavioral and social-emotional impairments.120–122 Collectively, these environmental toxins, as well as neighborhood characteristics including light, noise, and community violence,81,90 could account for variation in the neurobehavioral outcomes of children with SDB. Despite the growing body of research on neighborhood factors and pediatric sleep, additional work is needed to better understand the impacts of neighborhood exposures on SDB and its outcomes.

1.4. Conclusions and Future Directions

SDB is a prevalent multi-level pediatric health problem with deleterious impacts and well-documented racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in its prevalence, treatment, and outcomes. We have reviewed putative determinants of these disparities at multiple socio-ecological levels, including child and family sleep parameters, as well as racism and discrimination in schools, healthcare, and the built environment. Overall, these factors are understudied, and represent crucial directions for future SDB research. As most of the available research to date has focused on comparing Black to non-Latinx White youth, more investigations are needed that include youth of other racial and ethnic backgrounds based on each country’s socio-demographic profile. Of note, this review applies to typically developing children, as youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities have historically been excluded from large SDB trials.123 This is an area that also deserves further research. Much of the extant literature on factors linked to SDB disparities is cross-sectional and, as such, there is a need for longitudinal and mechanistic studies that allow for causal inference. Qualitative research that solicits child, caregiver, and healthcare clinician perspectives may also provide a more nuanced understanding clinical care and decision-making in SDB,124 among other potential socio-ecological determinants. Finally, research evaluating multi-level and modifiable determinants36 of pediatric SDB disparities is critical for informing the development of comprehensive interventions that can promote health equity for youth with SDB and their families.

Educational Aims.

At the end of this activity the reader will be able to:

Recognize the existence of health disparities in the prevalence of pediatric sleep-disordered breathing in the United States.

Summarize contributors to the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities affecting sleep-disordered breathing in children.

Distinguish that race and ethnicity are socio-political constructs and hence, disparities are due to social and environmental factors.

Future Directions:

Conduct longitudinal and mechanistic studies that allow for causal inference to better understand contributors to pediatric sleep-disordered breathing disparities.

Investigate sleep-related health disparities in youth with developmental disabilities.

Evaluate multi-level and modifiable determinants of pediatric sleep-disordered breathing disparities to inform interventions that mitigate these disparities.

Funding:

K23HD094905 (AAW); R01HL152454 (IET; AAW; TJJ); R61HL151253 (IET); R21HD101003 (IET).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin H-M, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in children in a general population sample: prevalence and risk factors. Sleep. 2009;32(6):731–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonuck KA, Chervin RD, Cole TJ, et al. Prevalence and persistence of sleep disordered breathing symptoms in young children: a 6-year population-based cohort study. Sleep. 2011;34(7):875–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen CL, Larkin EK, Kirchner HL, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in 8-to 11-year-old children: Association with race and prematurity. The Journal Of Pediatrics. 2003;142(4):383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders–third edition (icsd-3). Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: deliberations of the sleep apnea definitions task force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine. 2012;8(5):597–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep medicine. 2000;1(1):21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chervin RD, Weatherly RA, Garetz SL, et al. Pediatric sleep questionnaire: Prediction of sleep apnea and outcomes. Archives Of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2007;133(3):216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farr OM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Taveras EM, Mantzoros CS. Current child, but not maternal, snoring is bi-directionally related to adiposity and cardiometabolic risk markers: A cross-sectional and a prospective cohort analysis. Metabolism. 2017;76:70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horne RS, Yang JS, Walter LM, et al. Elevated blood pressure during sleep and wake in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e85–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redline S, Storfer-Isser A, Rosen CL, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing in adolescents. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;176(4):401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross KR, Storfer-Isser A, Hart MA, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing is associated with asthma severity in children. The Journal Of Pediatrics. 2012;160(5):736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus CL, Moore RH, Rosen CL, et al. A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(25):2366–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourke R, Anderson V, Yang JS, et al. Cognitive and academic functions are impaired in children with all severities of sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Medicine. 2011;12(5):489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brockmann PE, Urschitz MS, Schlaud M, Poets CF. Primary snoring in school children: prevalence and neurocognitive impairments. Sleep & Breathing. 2012;16(1):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isaiah A, Ernst T, Cloak CC, Clark DB, Chang L. Associations between frontal lobe structure, parent-reported obstructive sleep disordered breathing and childhood behavior in the ABCD dataset. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarasiuk A, Greenberg-Dotan S, Simon-Tuval T, et al. Elevated morbidity and health care use in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. American Journal Of Respiratory And Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennum P, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J. Morbidity and mortality in children with obstructive sleep apnoea: A controlled national study. Thorax. 2013;68(10):949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archbold KH, Pituch KJ, Panahi P, Chervin RD. Symptoms of sleep disturbances among children at two general pediatric clinics. The Journal Of Pediatrics. 2002;140(1):97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus C, Brooks LJ, Draper KA, Gozal D, Halbower AC, Jones J, Schechter MS, Sheldon SH, Spruyt K, Lehmann C, Shiffman RN. . Clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012;130:576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller GF, Coffield E, Leroy Z, Wallin R. Prevalence and costs of five chronic conditions in children. The Journal of School Nursing. 2016;32(5):357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang K-T, Chou C-H, Weng W-C, Lee P-L, Hsu W-C. Associations between adenotonsillar hypertrophy, age, and obesity in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Plos One. 2013;8(10):e78666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Zhao Y, Yang W, et al. Correlations between obstructive sleep apnea and adenotonsillar hypertrophy in children of different weight status. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beebe DW, Lewin D, Zeller M, et al. Sleep in overweight adolescents: shorter sleep, poorer sleep quality, sleepiness, and sleep-disordered breathing. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(1):69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C-F, Lee C-H, Hsueh W-Y, Lin M-T, Kang K-T. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2018;14(5):867–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boss EF, Smith DF, Ishman SL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in children. International Journal Of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2011;75(3):299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JP, Hardy ST, Hale LE, Gazmararian JA. Racial disparities and sleep among preschool aged children: A systematic review. Sleep Health. 2019;5(1):49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redline S, Tishler PV, Schluchter M, Aylor J, Clark K, Graham G. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children: Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problems. American Journal Of Respiratory And Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(5):1527–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus CL, Moore RH, Rosen CL, et al. A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2366–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinstock TG, Rosen CL, Marcus CL, et al. Predictors of obstructive sleep apnea severity in adenotonsillectomy candidates. Sleep. 2014;37(2):261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang R, Dong Y, Weng J, et al. Associations among neighborhood, race, and sleep apnea severity in children. A six-city analysis. Annals Of The American Thoracic Society. 2017;14(1):76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Kirchner HL, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage as a risk factor for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. The Journal Of Pediatrics. 2006;149(3):342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper JN, Koppera S, Boss EF, Lind MN. Differences in Tonsillectomy Utilization by Race/Ethnicity, Type of Health Insurance, and Rurality. Academic pediatrics. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kum-Nji P, Mangrem CL, Wells PJ, Klesges LM, HG H. Black/white differential use of health services by young children in a rural Mississippi community. South Med J. 2006;99(9):957–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boss EF, Benke JR, Tunkel DE, Ishman SL, Bridges JF, Kim JM. Public insurance and timing of polysomnography and surgical care for children with sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2015;141(2): 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beebe W Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: A comprehensive review. Sleep-New York Then Westchester-. 2006;29(9):1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson CL, Walker JR, Brown MK, Das R, Jones NL. A workshop report on the causes and consequences of sleep health disparities. Sleep. 2020;43(8):zsaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. 2020;10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bronfenbrenner U Ecological systems theory. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Billings ME, Cohen RT, Baldwin CM, et al. Disparities in Sleep Health and Potential Intervention Models: A Focused Review. Chest. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson AA, Mindell JA. Cumulative socio-demographic risk factors and sleep outcomes in early childhood. Sleep. 2020;43(3):zsz233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xanthopoulos MS, Williamson AA, Tapia IE. Positive airway pressure for the treatment of the childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones CP. Invited commentary:“race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. American journal of epidemiology. 2001;154(4):299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones CP. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon. 2003;50(1–2):7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloSone. 2015;10(9):e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health the added effects of racism and discrimination. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental psychology. 2002;38(2):179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, Carter RT. Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pratt M, Zeev-Wolf M, Goldstein A, Feldman R. Exposure to early and persistent maternal depression impairs the neural basis of attachment in preadolescence. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2019;93:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berry OO, Tobón AL, Njoroge WF. Social Determinants of Health: the Impact of Racism on Early Childhood Mental Health. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2021;23(5):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson RE, Hussain SB, Wilson MN, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Williams JL. Pathways to pain: Racial discrimination and relations between parental functioning and child psychosocial well-being. Journal of Black Psychology. 2015;41(6):491–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caughy MOB, O’Campo PJ, Muntaner C. Experiences of racism among African American parents and the mental health of their preschool-aged children. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(12):2118–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cave L, Cooper MN, Zubrick SR, Shepherd CC. Caregiver-perceived racial discrimination is associated with diverse mental health outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 7–12 years. International journal for equity in health. 2019;18(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ford KR, Hurd NM, Jagers RJ, Sellers RM. Caregiver experiences of discrimination and African American adolescents’ psychological health over time. Child Development. 2013;84(2):485–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slopen N, Lewis TT, Williams DR. Discrimination and sleep: a systematic review. Sleep medicine. 2016;18:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powell CA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, et al. Maternal experiences of racial discrimination and offspring sleep in the first 2 years of life: Project Viva cohort, Massachusetts, USA (1999–2002). Sleep health. 2020;6(4):463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goosby BJ, Cheadle JE, Strong-Bak W, Roth TC, Nelson TD. Perceived discrimination and adolescent sleep in a community sample. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 2018;4(4):43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huynh VW, Gillen-O’Neel C. Discrimination and sleep: The protective role of school belonging. Youth & Society. 2016;48(5):649–672. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fuller-Rowell TE, Nichols O1, Burrow AL, Ong AD, Chae DH, El-Sheikh M. Day-to-day fluctuations in experiences of discrimination: Associations with sleep and the moderating role of internalized racism among African American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2021;27(1):107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yip T, Cheon YM, Wang Y, Cham H, Tryon W, El-Sheikh M. Racial disparities in sleep: Associations with discrimination among ethnic/racial minority adolescents. Child development. 2020;91(3):914–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. J Pers. 2003;71(6): 1197–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin KH, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: a multilevel analysis. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(2):371–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paradies Y A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4): 888–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans. A biopsychosocial model. The American psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual review of psychology. 2007;58:201–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schulz A, Israel B, Williams D, Parker E, Becker A, James S. Social inequalities, stressors and self reported health status among African American and white women in the Detroit metropolitan area. Social science & medicine (1982). 2000;51 (11): 1639–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guglielmo D, Gazmararian JA, Chung J, Rogers AE, Hale L. Racial/ethnic sleep disparities in us school-aged children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Sleep Health. 2018;4(l):68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pena M-M, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW, Redline S, Taveras EM. Racial/ethnic and socio-contextual correlates of chronic sleep curtailment in childhood. Sleep. 2016;39(9): 1653–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine. 2016;12(6):785–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buxton OM, Chang A-M, Spilsbury JC, Bos T, Emsellem H, Knutson KL. Sleep in the modern family: Protective family routines for child and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wheaton AG, Ferro GA, Croft JB. School start times for middle school and high school students—united states, 2011–12 school year. Mmwr Morbidity And Mortality Weekly Report. 2015;64(30):809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Bub KL, Gillman MW, Oken E. Prospective study of insufficient sleep and neurobehavioral functioning among school-age children. Academic Pediatrics. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beebe DW. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics Of North America. 2011;58(3):649–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matthews KA, Pantesco EJ. Sleep characteristics and cardiovascular risk in children and adolescents: An enumerative review. Sleep Medicine. 2016;18:36–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moore M, Bonuck K. Comorbid symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing and behavioral sleep problems from 18–57 months of age: a population-based study. Behavioral sleep medicine. 2013;11(3):222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Byars K, Apiwattanasawee P, Leejakpai A, Tangchityongsiva S, Simakajornboom N. Behavioral sleep disturbances in children clinically referred for evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Medicine. 2011;12(2):163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bonuck K, Chervin RD, Howe LD. Sleep-disordered breathing, sleep duration, and childhood overweight: A longitudinal cohort study. The Journal Of Pediatrics. 2015;166(3):632–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meltzer LJ, Williamson AA, Mindell J. Pediatric sleep health: It matters, and so does how we define it. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williamson A, Milaniak I, Watson B, et al. Early childhood sleep intervention in urban primary care: Caregiver and clinician perspectives. Journal Of Pediatric Psychology. 2020;54(8):933–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McQuillan M, Bates J, Staples A, Deater-Deckard K. Maternal stress, sleep, and parenting. Journal Of Family Psychology: Jfp: Journal Of The Division Of Family Psychology Of The American Psychological Association (Division 43). 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bagley EJ, Kelly RJ, Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M. What keeps low-ses children from sleeping well: The role of presleep worries and sleep environment. Sleep Medicine. 2015;16(4):496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patrick KE, Millet G, Mindell JA. Sleep differences by race in preschool children: the roles of parenting behaviors and socioeconomic status. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2016;14(5):467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Crabtree VM, Korhonen JB, Montgomery-Downs HE, Jones VF, O’Brien LM, Gozal D. Cultural influences on the bedtime behaviors of young children. Sleep medicine. 2005;6(4):319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Atkinson L, Beitchman J, Gonzalez A, et al. Cumulative risk, cumulative outcome: A 20-year longitudinal study. Plos One. 2015;10(6):e0127650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kajeepeta S, Gelaye B, Jackson CL, Williams MA. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep medicine. 2015;16(3):320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Doane LD, Breitenstein RS, Beekman C, Clifford S, Smith TJ, Lemery-Chalfant K. Early life socioeconomic disparities in children’s sleep: The mediating role of the current home environment. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2019;48(l):56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boles RE, Halbower AC, Daniels S, Gunnarsdottir T, Whitesell N, Johnson SL. Family chaos and child functioning in relation to sleep problems among children at risk for obesity. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2017; 15(2): 114–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williford AP, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Predicting change in parenting stress across early childhood: Child and maternal factors. Journal Of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(2):251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simons LG, Wickrama K, Lee T, Landers-Potts M, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Testing family stress and family investment explanations for conduct problems among African American adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016;78(2):498–515. [Google Scholar]

- 90.El-Sheikh M, Bagley EJ, Keiley M, Elmore-Staton L, Chen E, Buckhalt JA. Economic adversity and children’s sleep problems: Multiple indicators and moderation of effects. Health Psychology. 2013;32(8):849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bathory E, Tomopoulos S, Rothman R, et al. Infant Sleep and Parent Health Literacy. AcadPediatr. 2016;16(6):550–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Blackson E, Gerdes M, TJ J. Implicit racial bias towards children in the early childhood setting. Journal of early childhood research, under review. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Starck JG, Riddle T, Sinclair S, Warikoo N. Teachers are people too: Examining the racial bias of teachers compared to other American adults. Educational Researcher. 2020;49(4):273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kunesh CE, Noltemeyer A. Understanding disciplinary disproportionality: Stereotypes shape pre-service teachers’ beliefs about black boys’ behavior. Urban Education. 2019;54(4):471–498. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Okonofua JA, Eberhardt JL. Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological science. 2015;26(5):617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carter PL, Skiba R, Arredondo MI, Pollock M. You can’t fix what you don’t look at: Acknowledging race in addressing racial discipline disparities. Urban education. 2017;52(2):207–235. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Halberstadt AG, Cooke AN, Gamer PW, Hughes SA, Oertwig D, Neupert SD. Racialized emotion recognition accuracy and anger bias of children’s faces. Emotion. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Halberstadt AG, Castro VL, Chu Q, Lozada FT, Sims CM. Preservice teachers’ racialized emotion recognition, anger bias, and hostility attributions. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2018;54:125–138. [Google Scholar]

- 99.American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: An evidentiary review and recommendations. The American Psychologist. 2008;63(9):852–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fabelo T, Thompson MD, Plotkin M, Carmichael D, Marchbanks MP, Booth EA. Breaking schools’ rules: A statewide study of how school discipline relates to students’ success and juvenile justice involvement. New York: Council of State Governments Justice Center. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nicholson-Crotty S, Birchmeier Z, Valentine D. Exploring the impact of school discipline on racial disproportion in the juvenile justice system. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90(4): 1003–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Warikoo N, Sinclair S, Fei J, Jacoby-Senghor D. Examining racial bias in education: A new approach. Educational Researcher. 2016;45(9):508–514. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kum-Nji PMC, Wells PJ, Klesges LM, Herrod HG. Black/white differential use of health services by young children in a rural Mississippi community. Southern Medical Journal. 2006;99(9):957–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Archives of internal medicine. 2005;165(15):1749–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57 Suppl 1:146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Van Ryn M Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Medical care. 2002:I140–I151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Social science & medicine. 2000;50(6):813–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lewis G, Croft-Jeffreys C, David A. Are British psychiatrists racist? Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22(9):1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sabin JA, Greenwald AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):988–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hooper EM, Comstock LM, Goodwin JM, Goodwin JS. Patient characteristics that influence physician behavior. Med Care. 1982;20(6):630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. American journal of public health. 2012;102(5):979–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Blair IV, Havranek EP, Price DW, et al. Assessment of biases against Latinos and African Americans among primary care providers and community members. American journal of public health. 2013;103(1):92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hagiwara N, Penner LA, Gonzalez R, et al. Racial attitudes, physician-patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The Effects of Oncologist Implicit Racial Bias in Racially Discordant Oncology Interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2874–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004;19(2):101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mayne SL, Mitchell JA, Virudachalam S, Fiks AG, Williamson AA. Neighborhood Environments and Sleep Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2021:101465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mattison DR. Environmental exposures and development. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2010;22(2):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rauh VA, Margolis AE. Research review: environmental exposures, neurodevelopment, and child mental health–new paradigms for the study of brain and behavioral effects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(7):775–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sanders T, Liu Y, Buchner V, Tchounwou PB. Neurotoxic effects and biomarkers of lead exposure: a review. Reviews on environmental health. 2009;24(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hendrix JA, Amon A, Abbeduto L, et al. Opportunities, barriers, and recommendations in down syndrome research. Translational Science of Rare Diseases. 2020(Preprint):1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Boss EF, Links AR, Saxton R, Cheng TL, Beach MC. Parent experience of care and decision making for children who snore. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2017;143(3):218–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]