Abstract

We designed five Pseudomonas-selective soil extract NAA media containing the selective properties of trimethoprim and sodium lauroyl sarcosine and 0 to 100% of the amount of Casamino Acids used in the classical Pseudomonas-selective Gould's S1 medium. All of the isolates were confirmed to be Pseudomonas by a Pseudomonas-specific OprF antibody and a Pseudomonas-specific PCR targeting 16S ribosomal DNA. The Pseudomonas isolates were characterized by classical physiological tests, repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and carbon source utilization patterns. Several of these analyses showed that the amount of Casamino Acids significantly influenced the diversity of the recovered Pseudomonas isolates. Furthermore, the data suggested that specific Pseudomonas subpopulations were represented on the nutrient-poor media. The NAA 1:100 medium, containing ca. 15 mg of organic carbon per liter, consistently gave significantly higher Pseudomonas CFU counts than Gould's S1 when tested on four Danish soils. NAA 1:100 may, therefore, be a better medium than Gould's S1 for enumeration and isolation of Pseudomonas from the low-nutrient soil environment.

Methods for examining bacterial numbers and diversity (26) can essentially be divided into culture-dependent and culture-independent ones. The major disadvantage of culturing is that one obtains only the organisms that can grow on a particular medium under the selected growth conditions. Although these may represent only a fraction of the total organisms in a given sample, it is nevertheless important to obtain pure cultures of interesting strains for further characterization or for use in biotechnology. Many authors have compared plate counts on different media (e.g., see references 6 and 20), but only a few have studied the effect of medium composition on the diversity represented by the isolates (15, 30). It has been demonstrated, though, that different media giving comparable plate counts can select for different bacterial types, leading to different estimates of diversity for the same soil (30).

The genus Pseudomonas includes several species of environmental interest, such as plant growth promoters (24), plant pathogens (28), and xenobiotic degraders (8, 13, 27). Due to the wide distribution of Pseudomonas in the environment and the ease by which these bacteria can be cultured, the genus today constitutes one of the best-studied bacterial groups. Nevertheless, new Pseudomonas species are described after application of new media or isolation procedures (1, 13). For isolation, media rich in nutrients, such as King's B (16) and Gould's S1 (7) agar, are traditionally used, but to our knowledge no authors have studied the impact of nutrient level in growth media on Pseudomonas numbers and diversity.

To identify and characterize bacteria, a number of different phenotypic and genotypic methods are available, each permitting a certain level of taxonomic classification (33). Traditionally, classification of bacteria has been conducted by using phenotypic tests, and the core of Pseudomonas taxonomy has been based on the ability of the isolates to utilize a variety of carbon compounds as the sole sources of carbon and energy (25). Nutritional characteristics still provide a good basis for characterization of isolates, but the analysis is time-consuming and should be combined with genotypic methods, especially when treating closely related bacteria. Repetitive extragenic palindromic (REP)-PCR (5) uses the conserved REP sequences originally found in Escherichia coli as primers for PCRs (34) to distinguish between bacteria at the subspecies level. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) is a physical technique which establishes specific spectral fingerprints of intact bacteria (21). FT-IR probes the total composition of a given organism, as spectra are influenced by the content of DNA, RNA, protein, membrane, and cell wall components. Consequently, FT-IR spectra are growth-stage dependent (21). Isolates can be identified using spectral data libraries or classified according to constructed phenograms or on the basis of multivariate statistical analysis. Characterization of environmentally isolated Pseudomonas strains by REP-PCR and FT-IR has previously been shown to correspond well (15).

Because soil is generally an oligotrophic environment, most heterotrophic bacteria indigenous to soil lack the ability to grow on nutrient media tested so far. The purpose of this study was to assess whether the amount of nutrients in the form of Casamino Acids in the isolation medium can affect the recovery of Pseudomonas isolates and their diversity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil samples and preparation of cold soil extracts.

Soil samples were obtained from six Danish localities: a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)-contaminated site near Ringe, a PAH-contaminated former shipyard site in Copenhagen, an agricultural area at the farm Højbakkegaard near Taastrup, an agricultural area in Græse near Frederikssund, a deciduous forest in Suserup Skov near Sorø, and a larch forest at Tornebakke near Slangerup. Soil properties are shown in Table 1. Only freshly collected soil was used in this study. To prepare cold soil extracts for use in growth media, the soil was air dried (20°C) and passed through a sieve (mesh size, 2 mm). The remaining part of the soil was kept at 5°C until used for enumeration of bacteria. The air-dried, sieved soil was then mixed 1:1 with Milli Q (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) water, and particles were removed by settling for 2 h and were centrifuged (5,000 × g, 20°C, 20 min). The supernatant was filter sterilized (pore size, 0.2 μm).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of soils used in this study

| Soil sample (origin) | % Coarse sand (>200 μm) | % Fine sand (63–200 μm) | % Coarse silt (20–63 μm) | % Fine silt (2–20 μm) | % Clay (<2 μm) | % Humus | % Total nitrogen | % Total carbon | % Moisture (dry wt) | pH (CaCl2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ringe (coal gasification plant) | 33.0 | 29.2 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 1.1 | 0.08 | 1.6 | 18.0 | 7.4 |

| Copenhagen (contaminated soil) | 52.2 | 25.6 | 1.0 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 0.08 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 7.6 |

| Højbakkegaard (agricultural soil) | 25.0 | 27.4 | 12.5 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 2.1 | 0.13 | 1.3 | 22.2 | 7.1 |

| Græse (agricultural soil) | 26.9 | 39.4 | 9.3 | 11.7 | 9.8 | 2.9 | 0.16 | 1.7 | 21.9 | 7.0 |

| Suserup Skov (deciduous forest floor) | 28.5 | 32.5 | 14.2 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 0.25 | 3.4 | 38.3 | 4.3 |

| Tornebakke (larch forest floor) | 25.1 | 34.1 | 13.7 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 5.1 | 0.23 | 3.0 | 12.2 | 4.5 |

Analyses performed by the Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Foulum, Denmark.

Preparation of growth media.

In order to estimate and compare the number of Pseudomonas CFU isolated on different agar media, plate counts were obtained from seven Pseudomonas-selective media. These were five cold soil extract (CSE) media with various levels of Casamino Acids (NAA 1:1, NAA 1:10, NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, and NAA 0), Gould's S1 (7), and King's B (16). The total number of culturable aerobic bacteria was also recovered on two general CSE media (CSE 1:1 and CSE 0).

The five Pseudomonas-selective NAA media consisted (per liter) of 900 ml of Winogradsky's salt solution (0.4 g of K2HPO4, 0.13 g of MgSO · 7H2O, 0.13 g of NaCl, 1.52 mg of MnSO4 · H2O, and 0.5 g of NH4NO3), 1.2 g of N-lauroyl sarcosine sodium salt (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), 100 ml of CSE (23), 18 g of Noble agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), 20 mg of trimethoprim (Sigma), 50 mg of nystatin (Sigma), and 5 g, 500 mg, 50 mg, 5 mg, or 0 mg of Casamino Acids (Difco), respectively, corresponding to 100, 10, 1, 0.1, and 0% of the amount of Casamino Acids found in Gould's S1. Trimethoprim and nystatin were diluted in Winogradsky's salt solution to 0.4 and 4 mg ml−1 and were filter sterilized (pore size, 0.2 μm) and added after the medium had been autoclaved and cooled to approximately 50°C. It was calculated that NAA 1:1, NAA 1:10, NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, and NAA 0 had an organic carbon content of 1,431, 144, 15, 3, and 1 mg/liter, respectively, based on the organic carbon content in the added CSE and Casamino Acids. We checked the ability of selected pure cultures to grow on carbon compound impurities in the sarcosine sodium salt and Noble agar. This gave rise to pinhead-size colonies emerging only after incubation at 20°C for 10 days. The two nonselective cold-extracted soil extract media were prepared as the NAA media, but N-lauroyl sarcosine sodium salt and trimethoprim were omitted. CSE 1:1 contained 5 g of Casamino Acids per liter, whereas CSE 0 did not contain Casamino Acids. All glassware used for preparing the media were placed in an acid bath (1 M HCl) for at least 12 h, rinsed thoroughly, and oven sterilized (14 h, 300°C) to reduce contamination with organic compounds.

Determination of number of CFU.

To extract bacteria, 2 g of freshly sieved soil was mixed with 18 ml of Winogradsky's salt solution and sonicated (Branson 2210; Branson Ultrasonic Corporation, Danbury, Conn.) in a glass tube for 20 s. Tenfold-dilution series were prepared from 1-ml aliquots of the extract, and triplicate 50-μl samples of appropriate dilutions were spread on the relevant media. The same aliquot was used to inoculate all media, and plates were spread alternately to give conditions as similar as possible. We checked that there was no difference between the diversities of colonies retrieved from replicate agar plates by isolation and characterization of 40 colonies from two Gould's S1 agar plates by REP-PCR and FT-IR (data not shown). The plates were incubated at 20°C, and colonies were counted regularly until no new colonies developed, the colony density was too high, or fungal hyphae appeared on the plates. Fluorescent colonies in UV light (302 nm) on all Pseudomonas-selective media were counted.

Selection of isolates for characterization.

Dilutions of the Copenhagen soil were spread plated on the five NAA media. Thirty-two isolates were randomly picked from plates representing each of the NAA media. Colonies on NAA 1:1 were isolated on day 2, colonies on NAA 1:10 were isolated on day 6, and colonies on NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, and NAA 0 were isolated on day 12. Isolates were streaked on 1% tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco) solidified with 1.8% BiTek agar (Difco) to assure purity and were incubated for 2 days (20°C). Each isolate was subsequently transferred to 1.8-ml cryo tubes containing 0.5 ml of 1% tryptic soy broth and incubated (20°C, ∼100 rpm) for 5 to 7 days. Thereafter, 0.5 ml of glycerol was added and the cultures were mixed and kept at −80°C. It was not possible to obtain living cultures from 22 out of 160 frozen stocks, and these isolates were not analyzed further.

For all subsequent work, strains were grown on 10% TSA (30°C) if not stated otherwise. Culture collection strains were included in the tests mentioned below to assure specificity and to evaluate the identification methods performed. Strains used were Pseudomonas aeruginosa DSM 50071T, Pseudomonas fluorescens I DSM 50090T, Pseudomonas putida A DSM 291T, and Pseudomonas chlororaphis DSM 50083T, unless stated otherwise.

Identification by Pseudomonas-specific immunoassay and Pseudomonas-specific PCR.

The isolates were verified as belonging to the genus Pseudomonas by using a Pseudomonas-specific antibody (17) and Pseudomonas-specific PCR (14, 31). A Pseudomonas-specific antibody directed against the OprF surface protein was used in a colony blotting assay as described by Kragelund et al. (17). P. fluorescens DF 57 (29) and E. coli DSM 498T were applied to the filters as positive and negative controls, respectively.

To complement the results from the colony-blotting assay, a Pseudomonas-specific PCR targeting 16S ribosomal DNA was performed. Template DNA of an isolate was prepared by boiling 300 μl of an overnight bacterial culture (10% TSA, 30°C) suspended in Milli Q water (optical density at 600 nm, 0.6) in a safe-lock Eppendorf tube for 10 min. The tubes were immediately cooled on ice and centrifuged (20,000 × g, 10 min, 5°C), and the supernatants were subsequently kept at −20°C until PCR was carried out essentially as previously described (14). The assay was modified by using 25 μl of master mix per reaction and Ampli Taq Gold polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, Conn.). The PSMG primer (3) in combination with the eubacterial primer 9-27 used for PCR gives Pseudomonas-specific amplification (14). To assure this specificity, PCR was first carried out on the five Pseudomonas and E. coli type strains. In each PCR run, a negative control without template DNA was included as well.

Characterization by classical biochemical tests.

To characterize the isolates the following tests were conducted: gram determination using the Bactident Aminopeptidase kit (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), oxidase (BBL Dryslide Oxidase Slides; Difco), catalase using 3% H2O2, and growth on 10% TSA at 4, 37, and 41°C.

REP-PCR analysis.

The isolates were characterized by REP-PCR with primers targeting repetitive extragenic palindromic elements (34). Template DNA was prepared as described above. PCR was carried out as previously described (13). The PCR was modified by using 2- to 4-μl template DNA suspension and 9.3 or 11.3 μl of double-distilled water per reaction mixture. Amplified PCR fragments were separated on 3% (wt/vol) LE agarose gels (20 by 20 cm) (Promega, Madison, Wis.). In each PCR run, a negative control without template DNA was included. Isolates showing similar band patterns were grouped manually. Electrophoresis was carried out again, with isolates belonging to the same REP-PCR group loaded next to each other to check similarity. Strains still giving faint or no band patterns after three trials were considered nontypeable.

FT-IR.

For FT-IR analysis, isolates from NAA 1:1, NAA 1:10, NAA 1:100, and NAA 1:1,000 were incubated overnight (30°C) on Luria broth (LB) agar supplemented with (per liter) 5 g of soluble starch, 10 ml of 1 M KPO4 (pH 7.0), and 8 ml of 50% glucose. Isolates from medium NAA 0, however, were not able to grow on LB agar and were grown on 10% TSA instead. A loopful of cells was used to inoculate tubes with 10 ml of TY broth, which contains (per liter) 20 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 0.7 ml of 1% FeCl2 · 4H2O, 0.1 ml of 1% Mn2Cl · 4H2O, 1.5 ml of 1% MgSO4 · 7H2O (pH 7.3). Tubes were incubated (30°C, 250 rpm) overnight until the cells were in the late log phase. FT-IR and cluster analyses were carried out on all isolates as previously described (15), but phenograms were based on 901 to 699, 1,200 to 900, and 3,001 to 2,799 parts cm−1 of the first derivative of the FT-IR spectrum. Clusters appearing in all three phenograms were considered groups.

Characterization by carbon source utilization patterns.

We tested the ability of the isolates to grow on a minimal medium (13) supplemented with 31 different carbon compounds on microtiter plates. The following carbon compounds were selected on the basis of Pseudomonas nutritional properties given by Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (25) and were used at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1: β-alanine, adipic acid, capric acid, citric acid, d-galactose, d-gluconic acid, d-glucose, d-maltose, d-mannitol, d-mannose, d-sorbitol, d-trehalose, fumaric acid, geraniol, glycerol, glycolic acid, l-arabinose, l-leucine, l-malic acid, l-phenylalanine, l-trypthophan, l-valine, meso-inositol, mucic acid, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, nicotinic acid, oxalate, phenylacetate, pyruvic acid, starch, and succinic acid. Two days prior to inoculation isolates from freeze cultures were streaked on 10% TSA (30°C). On the day of inoculation a sterile cotton stick was used to transfer bacteria to a glass tube with minimal medium and the bacterial concentration was adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3. Each microtiter plate well was inoculated with 180 μl of medium and 20 μl of the bacterial suspension. The plates were read immediately using a 650-nm-wavelength filter in a microtiter plate reader (Thermo max; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The plates were then incubated at 30°C for 43 h and read again. The experiment was run in triplicate. Absorbances of the wells without carbon compound were subtracted before data was subject to statistical analysis.

Statistics.

All cell counts were subject to t test. Groupings based on classical tests, REP-PCR, and FT-IR were statistically evaluated using the χ2 test or Fisher's Exact test when data were in 2-by-2 contingency tables. In cases where more than 20% of the expected values in χ2 test were less than 5, groups of media and/or groups of isolates were pooled to increase the number of expected values. Statistics for cell counts and groups were performed in Sigma Stat 2.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.). Data from the carbon utilization tests were further subject to pattern recognition analysis by means of disjoint principal components analysis (PCA) using the classification method SIMCA (35) in MATLAB PLS_Toolbox 2.0E Version 5.3 (Eigenvector Research, Inc., Manson, Wash.). Carbon utilization data were mean centered before analysis. In brief, the isolation media were considered separate classes and were modeled by their own principal component (PCA) models. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Viable cell counts.

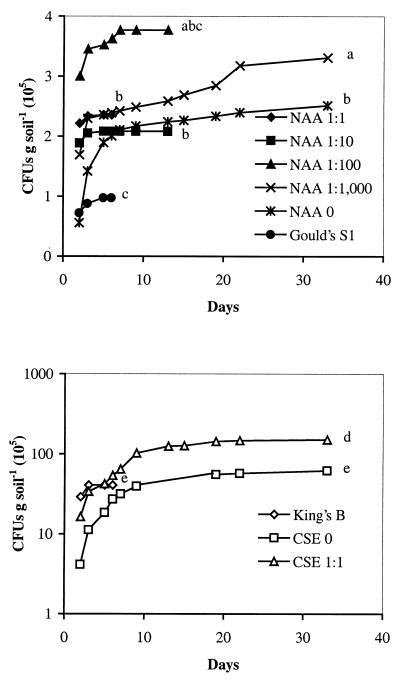

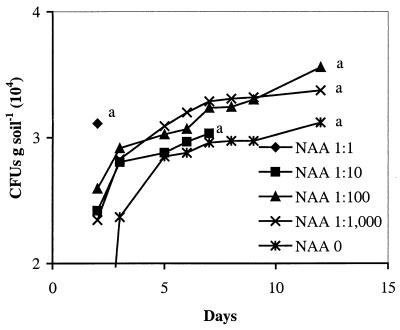

For the Ringe soil, Gould's S1 agar resulted in the lowest estimate of the Pseudomonas population of 9.8 × 104 CFU g of soil−1, as observed by the end of the incubation period (Fig. 1A). All NAA media except that from NAA 1:100 yielded significantly higher plate counts than Gould's S1, exceeding the number recovered on Gould's S1 by two- to fourfold, within the same incubation period. The highest plate count was obtained on NAA 1:100, although differences between NAA media were not statistically significant. Plating on King's B agar resulted in 4.1 × 106 CFU g of soil−1, or 2.1 × 105 (± 8.9 × 104) fluorescent Pseudomonas CFU g of soil−1, as observed in UV light. The total number of aerobic bacteria was determined on CSE 0 and CSE 1:1, yielding 6.2 × 106 and 1.5 × 107 CFU g of soil−1 (Fig. 1B). A further comparison of the recovery in four more soils with very different soil characteristics showed that the number of CFU was significantly higher on NAA 1:100 than on Gould's S1 agar in all four soils (Table 2). The Copenhagen soil harbored a smaller Pseudomonas population than the other tested soils (compare Table 2 and Fig. 1 and 2). Again, the highest plate counts were obtained from NAA 1:100, although the differences between NAA media were not statistically significant.

FIG. 1.

The number of CFU per gram of Ringe soil on seven Pseudomonas-selective media and two general media. Different letters indicate significantly different (P < 0.05) levels of CFU per gram of soil at the end of the incubation period. (A) NAA 1:1, NAA 1:10, NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, NAA 0, and Gould's S1; (B) CSE 1:1, CSE 0, and King's B agar.

TABLE 2.

The number of CFU per g of soil on Gould's S1 and NAA 1:100 agar for four different Danish soils

| Medium | No. of CFU per g of the following soilsa:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Højbakkegaard | Græse | Suserup Skov | Tornebakke | |

| Gould's S1 | 8.9 × 105 ± 2.8 × 105 | 1.3 × 105 ± 1.9 × 104 | 1.1 × 105 ± 2.8 × 104 | 7.8 × 103 ± 3.2 × 103 |

| NAA 1:100 | 2.6 × 106 ± 9.6 × 105 | 3.8 × 105 ± 1.1 × 105 | 4.4 × 105 ± 6.1 × 104 | 7.3 × 104 ± 8.0 × 103 |

Gould's S1 enumerations were made on days 3, 3, 5, and 5, respectively, and NAA 1:100 enumerations were made on days 10, 7, 10, and 10, respectively.

FIG. 2.

The number of CFU per gram of Copenhagen soil on NAA 1:1, NAA 1:10, NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, and NAA 0. Different letters indicate significantly different (P < 0.05) levels of CFU per gram of soil by the day of isolation.

Identification of isolates by Pseudomonas-specific immunoassay and Pseudomonas-specific PCR.

The diversity represented on the different NAA media was compared in an experiment with the Copenhagen soil. First, the specificity of the NAA media for Pseudomonas was verified. All isolates were identified as Pseudomonas by a colony-blotting procedure employing a Pseudomonas-specific OprF antibody (Table 3). Correspondingly, Pseudomonas-specific PCR and gel electrophoretic analysis of all isolates and the culture collection strains confirmed the presence of one band of the correct size (445 bp), suggesting that all isolates belonged to the genus Pseudomonas (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Identification and characterization of isolates

| Test or characteristic | % Positive isolates from

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA 1:1 (n = 27) | NAA 1:10 (n = 30) | NAA 1:100 (n = 30) | NAA 1:1,000 (n = 26) | NAA 0 (n = 25) | |

| OprF immunoblot | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Pseudomonas-specific PCR | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Gram negative | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Oxidase | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Catalase | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Growth at 4°C | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 |

| Growth at 37°C | 7 | 20 | 27 | 19 | 8 |

| Growth at 41°C | 4 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 8 |

Characterization by classical tests.

At primary isolation, the percentage of fluorescent colonies on NAA 1:1, NAA 1:10, NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, NAA 0, Gould's S1, and King's B plates was 68% ± 10%, 68% ± 37%, 0% ± 0%, 8% ± 13%, 16% ± 13%, 86% ± 23%, and 5% ± 2%, respectively. All 138 isolates were gram negative and were oxidase and catalase positive (Table 3). In the temperature tests 99% of the isolates were capable of growth at 4°C, 17% were capable of growth at 37°C, and 7% were capable of growth at 41°C. The proportion of isolates growing at the respective temperatures were not significantly different between the media.

Grouping by REP-PCR, FT-IR, and phenotypic tests.

Using REP-PCR, 106 isolates were typeable, among which 72 formed groups with at least one other isolate, constituting 11 groups (Table 4). Five different REP-PCR groups and 11 unique isolates originated from NAA 1:100, which thereby represented more REP-PCR groups than any other medium. The distribution of REP-PCR groups was significantly different between the media below (NAA 0 and 1:1,000) and above (NAA 1:1, 1:10, and 1:100) 15 mg of carbon per liter. Fifteen milligrams of carbon per liter is the limit below which Kuznetsov et al. (18) designate bacteria as oligotrophic. In particular, group IV isolated from NAA 1:1,000 appears to be medium specific, suggesting the existence of unique Pseudomonas subpopulations on the nutrient-poor media. None of the reference strains fitted into any of the REP-PCR groups, indicating that no isolates are closely related to these strains.

TABLE 4.

Grouping by REP-PCR, the number of isolates per medium in each group, and correspondence with growth temperatures

| REP-PCR groupa | No. of isolates grouped inb:

|

Growth at:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA 1:1 (n = 22) | NAA 1:10 (n = 20) | NAA 1:100 (n = 23) | NAA 1:1,000 (n = 19) | NAA 0 (n = 22) | 4°C | 37°C | 41°C | |

| I (n = 13) | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | + | − | − | |

| II (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | |||

| III (n = 12) | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | + | − | − | |

| IV (n = 6) | 6 | + | − | − | ||||

| V (n = 3) | 3 | + | − | − | ||||

| VI (n = 8) | 1 | 1 | 6 | + | − | − | ||

| VII (n = 7) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | |

| VIII (n = 4) | 4 | + | + | − | ||||

| IX (n = 10) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | + | + | +c |

| X (n = 3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | ||

| XI (n = 4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | ||

Only REP-PCR groups with at least two members are given (parenthetically after Roman numeral).

Number of isolates not assigned to an REP-PCR group: NAA 1:1, 8; NAA 1:10, 5; NAA 1:100, 11; NAA 1:1,000, 4; NAA 0, 6.

Two isolates were negative.

All isolates were typeable by using FT-IR, and cluster analysis in FT-IR by complete linkage, average linkage, and Ward's algorithm yielded very similar groups (data not shown). We formed FT-IR groups when isolates were grouped together by all three methods. Only 19 isolates did not fall into any FT-IR group (Table 5). Again, isolates from NAA 1:100 represented the highest number of groups constituting 19 FT-IR groups. The distribution of FT-IR groups was significantly different between media below (NAA 0 and 1:1,000) and above (NAA 1:1, 1:10 and 1:100) 15 mg of carbon per liter. The FT-IR groups F and I, originating from NAA 1:1,000 and NAA 0, respectively, were larger medium-specific groups, again supporting the existence of specific Pseudomonas populations on low-nutrient media. In general, there was good agreement between the groups formed by FT-IR and REP-PCR. For instance, the REP-PCR groups IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII were analogous to the FT-IR groups F, H, I, J, and S. The FT-IR technique generally resulted in formation of more and smaller groups than REP-PCR, but two FT-IR groups fitted into the same REP-PCR group on some occasions, and on one occasion two REP-PCR groups clustered in the same FT-IR group (data not shown). The groups formed by the two typing methods coincided very well with the classical phenotypic tests. In general, isolates sharing REP-PCR and FT-IR groups grew at the same temperatures (Table 4).

TABLE 5.

Grouping by FT-IR

| FT-IR groupa | No. of isolates grouped inb:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA 1:1 (n = 27) | NAA 1:10 (n = 30) | NAA 1:100 (n = 30) | NAA 1:1,000 (n = 26) | NAA 0 (n = 25) | |

| A (n = 8) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| B (n = 11) | 4 | 5 | 2 | ||

| C (n = 11) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| D (n = 2) | 2 | ||||

| E (n = 9) | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| F (n = 6) | 6 | ||||

| G (n = 3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| H (n = 3) | 3 | ||||

| I (n = 6) | 6 | ||||

| J (n = 6) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| K (n = 4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| L (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | |||

| M (n = 6) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| N (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | |||

| O (n = 4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| P (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Q (n = 2) | 2 | ||||

| R (n = 2)c | 1 | ||||

| S (n = 4) | 4 | ||||

| T (n = 2)d | 1 | ||||

| U (n = 2)e | |||||

| V (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | |||

| X (n = 4) | 4 | ||||

| Y (n = 7) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| AA (n = 2) | 2 | ||||

| AB (n = 3) | 1 | 2 | |||

| AC (n = 3) | 2 | 1 | |||

| AD (n = 2) | 2 | ||||

| AE (n = 3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

Only FT-IR groups with at least two members are given (parenthetically after letters).

Number of isolates not assigned to an FT-IR group: NAA 1:1, 3; NAA 1:10, 2; NAA 1:100, 6; NAA 1:1,000, 5; NAA 0, 3.

This group contains P. putida A DSM 291T.

This group contains P. fluorescens bv. I DSM 50 090T.

This group contains P. aeruginosa DSM 50 071 and P. chlororaphis DSM 50 083T.

Carbon source utilization data.

PCA on carbon utilization data coincided well with grouping appearing after FT-IR and REP-PCR analysis, showing that colonies appearing on the NAA 1:100 medium represented the highest proportion of unique strains analyzed by SIMCA (data not shown). The PCA model based on all carbon utilization rate data explained 81% of the variation. PC1 and PC2 each explained 47 and 19% of the variation, respectively, and this variation was largely governed by the utilization rates of d-mannitol, d-mannose, d-sorbitol, d-trehalose, glycerol, l-arabinose, meso-inositol, succinic acid, l-valine, and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine. The proportion of isolates able to grow on selected carbon compounds is shown in Table 6. The proportions of isolates able to grow on the remaining carbon compounds were the following: β-alanine, 92%; adipic acid, 0%; capric acid, 100%; citric acid, 100%; d-galactose, 88%; d-gluconic acid, 99%; d-glucose, 100%; d-maltose, 2%; fumaric acid, 99%; geraniol, 1%; glycerol, 99%; glycolic acid, 0%; l-leucine, 99%; l-malic acid, 7%; l-phenylalanine, 76%; l-valine, 96%; mucic acid, 99%; nicotinic acid, 6%; oxalate, 0%; phenylacetate, 1%; pyruvic acid, 99%; starch, 0%; and succinic acid, 99%. The isolates from NAA 0 had a significantly narrower carbon source utilization profile than isolates from the other NAA media in the sense that there were proportionally fewer positive tests for NAA media than for the isolates from other media.

TABLE 6.

Carbon source utilization profiles for isolates recovered on the various NAA media

| Carbon compound | % Positive isolates ona:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA 1:1 | NAA 1:10 | NAA 1:100 | NAA 1:1,000 | NAA 0 | |

| N-Acetyl-d-glucosamine | 89 | 90 | 67 | 74 | 88 |

| l-Arabinose | 30 (4) AB | 40 AB | 53 (3) A | 48 AB | 24 (4) B |

| meso-Inositol | 26 | 17 | 30 | 37 | 24 |

| d-Mannitol | 81 | 77 | 80 | 89 (4) | 72 |

| d-Mannose | 81 (7) AB | 83 (3) AB | 87 (10) AB | 93 A | 68 (8) B |

| d-Sorbitol | 19 AB | 17 AB | 30 A | 30 A | 4 B |

| d-Trehalose | 33 | 30 | 33 | 52 | 28 |

| l-Tryptophan | 7 (3) AB | 10 AB | 7 AB | 22 A | 0 B |

Different letters indicate significantly different (P < 0.05) proportions of positive isolates. Numbers in parentheses are percentages of which only two of three replicates are positive.

DISCUSSION

Pseudomonas-specific NAA media.

The NAA media are derived from the classical Gould's S1 Pseudomonas isolation medium (7) and contain the selective agent trimethoprim against facultative gram-negative bacteria (7). Yao and Moellering (36) state that trimethoprim is an inhibitor of DNA synthesis and is active against many gram-positive cocci and most gram-negative bacilli. Sodium lauroyl sarcosine prevents the growth of gram-positive bacteria (7). These selective compounds were also used by Andersen and coworkers (2) when they constructed a medium for the isolation of phenanthrene-degrading Pseudomonas isolates. In Gould's S1 medium, sucrose and glycerol are included to create an osmotic stress that selects for Pseudomonas, but apparently we could omit these compounds in the NAA media without problems. Cold soil extract was included, as environmental extracts can replace some ingredients in media used for enumeration and isolation of specific bacteria (reviewed by Lochhead and Burton [19]). Viable cell counts on the five NAA soil extract media, which vary in amino acid content, significantly exceed those obtained on Gould's S1 medium (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The media are specific for Pseudomonas, as shown by two independent molecular methods targeting the outer membrane protein OprF (17) and the 16S ribosomal DNA (14), respectively.

When tested for several different soils, Pseudomonas-specific counts on NAA 1:100 were at least threefold higher than counts on Gould's S1 (Table 2), and NAA 1:100 yielded the highest number of bacterial groups within a relatively short incubation time. Hence, although Pseudomonas is considered an organism typical for nutrient-rich media, the NAA 1:100 medium appears to be useful for enumeration and isolation of Pseudomonas from the low-nutrient soil environment. This medium contains an amino acid concentration of 50 mg liter−1. In accordance with this fact, Olsen and Bakken (23) found higher heterotrophic colony counts on general soil extract media containing 7 and 70 mg of nutrient mixture liter−1 than on media with 0, 700, or 7,000 mg liter−1. A negative effect of media with high nutrient concentrations on colony formation has often been observed for the quantification of bacteria in both soil (10, 11) and water (4). For instance, Hattori and Hattori (9) found that dilute nutrient broth organisms, considered oligotrophs, were severely suppressed by 1 or 2% (wt/vol) Casamino Acids.

Kuznetsov et al. (18) classified oligotrophs as bacteria that develop on media with an organic carbon content of about 1 to 15 mg liter−1 at first cultivation. Other authors have suggested that the term oligotrophs should be used for bacteria which do not form colonies on high-nutrient media at the first cultivation, though this definition is much more difficult to use experimentally (22, 23). Using Kuznetsov's definition, the strains isolated on NAA 1:100, NAA 1:1,000, and NAA 0 with organic carbon contents of approximately 15, 3, and 1 mg per liter, respectively, can be classified as oligotrophs (18). All isolates were maintained on 1% tryptic soy broth after the first cultivation step. However, the strains from NAA 0 could not be recultivated on the rich LB agar, suggesting that these isolates are nutritionally different from the isolates recovered on the other media. We propose that the Pseudomonas strains recovered on low-nutrient NAA media may include specific groups that can grow on richer media at subsequent recultivation. This group is defined as facultative oligotrophs by Ishida et al. (12).

Pseudomonas diversity.

The concentration of Casamino Acids in the NAA media had a significant effect on the diversity represented by the Pseudomonas isolates as shown by both genotypic and phenotypic typing methods. The data suggest that unique Pseudomonas groups occur on the more nutrient-poor media. These subpopulations might occupy other ecological niches than Pseudomonas strains obtained on the traditional nutrient-rich Pseudomonas isolation media King's B (16) and Gould's S1 (7) and could represent new species.

Hence, we have shown that by varying the level of Casamino Acids in a Pseudomonas-selective growth medium, significantly different assessments of diversity will be obtained from the same soil. Other authors have shown that the media used for isolation play an important role in the study of bacterial diversity. For example, Sørheim et al. (30) demonstrated that the carbon source of a general soil extract medium influenced the bacterial diversity markedly. Not much literature, however, exists on comparative diversity studies of strains isolated on eu- and oligotrophic media that are otherwise comparable. The culture-dependent techniques may seem inadequate for addressing bacterial diversity, since only about 1 to 5% of the total bacterial population can be readily cultivated using the media known so far (23) and soil most likely contains a vast number of virtually unknown bacteria. Torsvik et al. (32) found that the diversity of the total bacterial community estimated by reassociation analysis of DNA isolated directly from soil was approximately 170 times higher than the diversity represented by cultured strains from the same soil. Even though culture-independent DNA-based methods are powerful tools for diversity studies, microbiologists will still be dependent on cultivation methods to obtain pure cultures for further physiological characterization. Hopefully, further attention to culturing methods might reduce the huge gap between the culturable and nonculturable bacterial community and provide a better understanding of the soil ecosystem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by BIOPRO (Centre for biological processes in contaminated soils and sediments) established under The Danish Environmental Research Programme (www.biopro.dk).

We gratefully thank Per Rosenberg for excellent multivariate statistical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen S M, Johnsen K, Sørensen J, Nielsen P, Jacobsen C S. Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis sp. nov., isolated from soil at a coal gasification site. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1957–1964. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-6-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen S M, Jørgensen C, Jacobsen C S. Development and utilisation of a medium to isolate phenanthrene-degrading Pseudomonas spp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:112–116. doi: 10.1007/s002530000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun-Howland E B, Vescio P A, Nierzwicki-Bauer S A. Use of a simplified cell blot technique and 16S rRNA-directed probes for identification of common environmental isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3219–3224. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3219-3224.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck J D. Effects of medium composition on the recovery of bacteria from sea water. J Exp Marine Biol Ecol. 1974;15:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bruijn F J. Use of repetitive (repetitive extragenic palindromic and enterobacterial repetitive intergeneric consensus) sequences and the polymerase chain reaction to fingerprint the genomes of Rhizobium meliloti isolates and other soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2180–2187. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2180-2187.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott M L, Jardin E A D. Comparison of media and diluents for enumeration of aerobic bacteria from Bermuda grass golf course putting greens. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;34:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gould W D, Hagedorn C, Bardinelli T R, Zablotowicz R M. New selective media for enumeration and recovery of fluorescent pseudomonads from various habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:28–32. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.1.28-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harayama S, Timmis K N. Catabolism of aromatic hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas. In: Chater K F, editor. Genetics of bacterial diversity. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hattori R, Hattori T. Sensitivity to salts and organic compounds of soil bacteria isolated on diluted media. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1980;26:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hattori T. A note on the effect of different types of agar on plate count of oligotrophic bacteria in soil. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1980;26:373–374. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hattori T. Enrichment of oligotrophic bacteria at microsites of soil. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1981;27:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishida Y, Imai I, Miyagaki T, Kadota H. Growth and uptake kinetics of a facultatively oligotrophic bacterium at low nutrient concentrations. Microb Ecol. 1982;8:23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02011458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnsen K, Andersen S, Jacobsen C S. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of phenanthrene-degrading fluorescent Pseudomonas biovars. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3818–3825. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3818-3825.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnsen K, Enger Ø, Jacobsen C S, Thirup L, Torsvik V. Quantitative selective PCR of 16S ribosomal DNA correlates well with selective agar plating in describing population dynamics of indigenous Pseudomonas spp. in soil hot spots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1786–1788. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1786-1788.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnsen K, Nielsen P. Diversity of Pseudomonas strains isolated with King's B and Gould's S1 agar determined by repetitive extragenic palindromic-polymerase chain reaction, 16S rDNA sequencing and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy characterisation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;173:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King E O, Ward M K, Raney D E. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kragelund L, Leopold K, Nybroe O. Outer membrane protein heterogeneity within Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. putida and use of an OprF antibody as a probe for rRNA homology group I pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:480–485. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.480-485.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuznetsov S I, Dubinina G A, Lapteva N A. Biology of oligotrophic bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1979;33:377–387. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.33.100179.002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lochhead A G, Burton M O. Importance of soil extract for the enumeration and study of soil bacteria. Sixième congrès de la science du sol III. 1956;26:157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin J K. Comparison of agar media for counts of viable bacteria. Soil Biol Biochem. 1975;7:401–402. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naumann D, Helm D, Labischinski H. Microbiological characterizations by FT-IR spectroscopy. Nature. 1991;351:81–82. doi: 10.1038/351081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohta H, Hattori T. Oligotrophic bacteria on organic debris and plant roots in paddy field soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 1983;15:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen R A, Bakken L R. Viability of soil bacteria: optimization of plate-counting technique and comparison between total counts and plate counts within different size groups. Microb Ecol. 1987;13:59–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02014963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Sullivan D J, O'Gara F. Traits of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. involved in suppression of plant root pathogens. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:662–676. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.662-676.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palleroni N J. Pseudomonadaceae. In: Tansill B, editor. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 141–199. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pankhurst C E, Ophel-Keller K, Doube B M, Gupta V V S R. Biodiversity of soil microbial communities in agricultural systems. Biodivers Conserv. 1996;5:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridgway H F, Safarik J, Phipps D, Carl P, Clark D. Identification and catabolic activity of well-derived gasoline-degrading bacteria from a contaminated aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3565–3575. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3565-3575.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroth M N, Hildebrand D C, Panopoulos N. Phytopathogenic pseudomonads and related plant-associated pseudomonads. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 3104–3131. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sørensen J, Skouv J, Jørgensen A, Nybroe O. Rapid identification of environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida by SDS-PAGE analysis of whole-cell protein patterns. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1992;101:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sørheim R, Torsvik V L, Goksøyr J. Phenotypical divergences between populations of soil bacteria isolated on different media. Microb Ecol. 1989;17:181–192. doi: 10.1007/BF02011852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thirup L, Johnsen K, Winding A. Succession of indigenous Pseudomonas spp. and actinomycetes on barley roots affected by the antagonistic strain Pseudomonas fluorescens DR54 and the fungicide imazalil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1147–1153. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1147-1153.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torsvik V, Salte K, Sørheim R, Goksøyr J. Comparison of phenotypic diversity and DNA heterogeneity in a population of soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:776–781. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.776-781.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandamme P, Pot B, Gillis M, de Vos P, Kersters K, Swings J. Polyphasic taxonomy, a consensus approach to bacterial systematics. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:407–438. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.407-438.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6832. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wold S. Pattern recognition by means of disjoint principal components models. Pattern Recognition. 1976;8:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao J D C, Moellering R C., Jr . Antibacterial agents. In: Murray P R, editor. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 1474–1504. [Google Scholar]