Abstract

With the intensive development of polymeric biomaterials in recent years, research using drug delivery systems (DDSs) has become an essential strategy for cancer therapy. Various DDSs are expected to have more advantages in anti-neoplastic effects, including easy preparation, high pharmacology efficiency, low toxicity, tumor-targeting ability, and high drug-controlled release. Polyurethanes (PUs) are a very important kind of polymers widely used in medicine, pharmacy, and biomaterial engineering. Biodegradable and non-biodegradable PUs are a significant group of these biomaterials. PUs can be synthesized by adequately selecting building blocks (a polyol, a di- or multi-isocyanate, and a chain extender) with suitable physicochemical and biological properties for applications in anti-cancer DDSs technology. Currently, there are few comprehensive reports on a summary of polyurethane DDSs (PU-DDSs) applied for tumor therapy. This study reviewed state-of-the-art PUs designed for anti-cancer PU-DDSs. We studied successful applications and prospects for further development of effective methods for obtaining PUs as biomaterials for oncology.

Keywords: biomaterials, drug delivery systems, anti-cancer drug delivery systems, biomedical polyurethanes, biodegradable polyurethanes, polyurethane chemistry

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, the number of cancer cases is expected to reach 22 million per year by 2035 [1]. Surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are the most common cancer treatments. Chemotherapy is the most frequently used systemic treatment for suppressing cancer cell proliferation, disease progression, and metastasis. However, chemotherapeutic drugs also inevitably attack normal cells, causing dangerous adverse effects. Therefore, new anti-cancer drug delivery systems (DDSs) that maintain or improve the efficacy of chemotherapy while reducing the severity of reactions and side effects are urgently needed [2,3,4,5,6].

DDSs are a particular type of biomaterials. Biomaterials are defined as any natural, semi-synthetic, or synthetic substances engineered to interact with biological systems in order to direct medical treatment or diagnostics. These materials must be biocompatible, meaning they perform their function with an appropriate host response. Biomaterials can be generally divided into the following groups: polymers, metals, ceramics, carbon materials, and various composites [5,7].

Biodegradable or bioresorbable polymers are of utmost interest since these biomaterials can be broken down, excreted, or resorbed without removal or surgical revision. One of the most promising groups of biomedical and biodegradable polymers is aliphatic or cycloaliphatic polyurethanes (PUs) [8,9]. PUs are popular because of their segmented-block structure, which endows them with a broad range of versatility in terms of tunable mechanical, physicochemical, and biological properties, as well as blood and tissue compatibility and their biodegradability. PUs are characterized by valuable and unique physicochemical properties that are very important for biomedical applications. The soft segments determine the low glass-transition temperature (Tg) or high elasticity of PUs. The hard segments determine the high Tg, melting point (Tm), or high strength of PUs. The values of fail stress and elongation at break are 5–230 MPa and 200–1300%, respectively. PUs are also characterized by corrosion resistance, high gloss and weathering resistance [10,11,12,13,14].

PUs have traditionally been used as biostable and inert materials in catheters, heart valves, prostheses, and vascular grafts [10,11,12,13]. However, interest in designing resorbable/degradable PUs for tissue engineering and drug delivery systems (DDSs) has also been increasing in recent years [10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Biomedical PUs (BioPUs) can be synthesized by incorporating hydrolyzable segments into their backbones (e.g., polyether, polyester, and polyamide segments). A second strategy for making such PUs is to use amino-acid-derived diisocyanates and biocompatible aliphatic or cycloaliphatic diisocyanates (ICs) in the synthesis. These components have lower toxicity than traditional ICs, such as 4,4′-methylenebis(phenyl isocyanate) (MDI) and toluene 2,4-diisocyanate (TDI). An additional benefit of such PUs is their proven ability to promote cell adhesion and proliferation without adverse effects [10,13,15,19].

Recent developments of BioPUs as short-, medium-, or long-term anti-cancer DDSs are described in detail in this review.

2. Synthesis and Properties of Biomedical Polyurethanes Used in Anti-Cancer Drug Delivery Systems

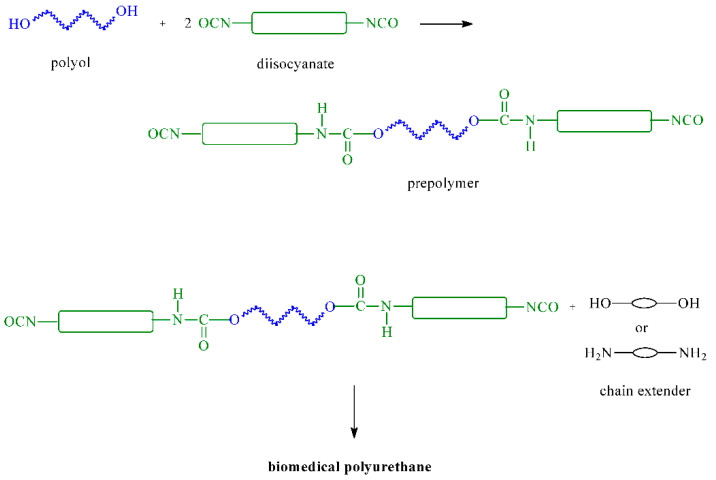

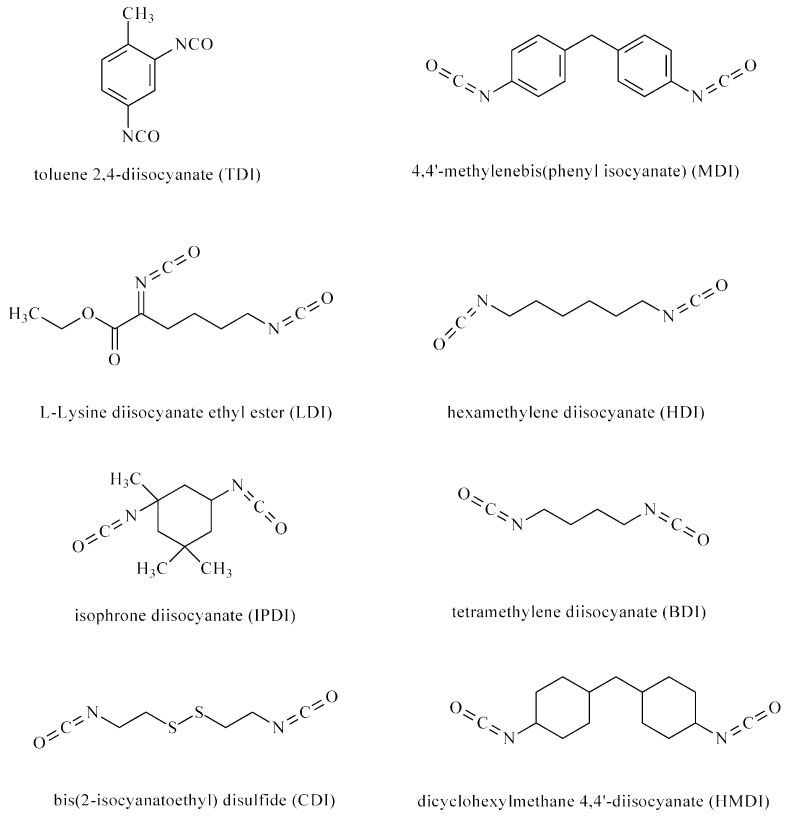

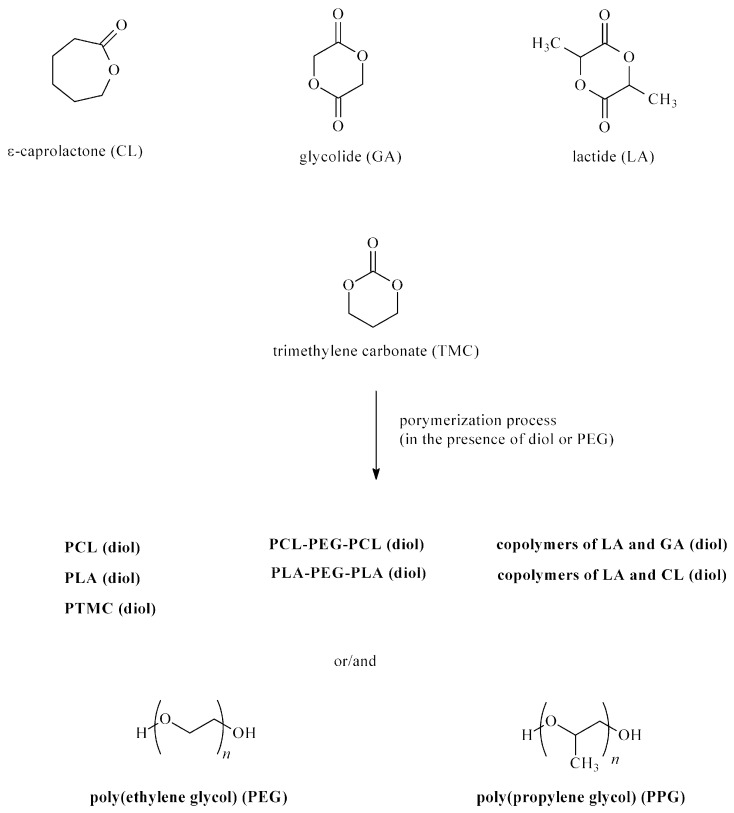

BioPUs can be obtained through the polyaddition or polycondensation processes. The polyaddition process involves ICs reacting with bi- or multi-functional polyols, polyamines, alcohols, and amines. BioPUs are obtained in a one- or two-step method (prepolymer method). In the first step of the second method, polyols are continuously stirred with ICs, and the obtained prepolymers are then extended using chain extenders (such as a diol or diamine) (Figure 1). Different types of ICs (aromatic, aliphatic, and cycloaliphatic) are used in BioPU synthesis: TDI, MDI, L-lysine diisocyanate ethyl ester (LDI), hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI), isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI), bis(2-isocyanatoethyl) disulfide (CDI), dicyclohexylmethane 4,4′-diisocyanate (HMDI), and tetramethylene diisocyanate (BDI) (Figure 2). Polyols are used polyesters (e.g., poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and polylactide (PLA)), polyethers (e.g., poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and poly(propylene glycol) (PPG)), and polycarbonates (poly(trimethylene carbonate) (PTMC), poly(ester-carbonate)s, and copolymers of cycle monomers (e.g., glycolide (GG) and lactide (LA)) (Figure 3). The polyols are usually prepared using ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of heterocyclic monomers (e.g., esters and carbonates) in the presence of cationic or anionic initiators, enzymes, and coordination catalysts. Chain extenders are often used, such as 1,4-butanediol (BDO), diethylene glycol (DEG), ethylene glycol (EG), 1,3-propanediol (PDO), 1,4-diaminobutane (1,4-DAB), 1,2-diaminoethane (1,2-DAE), 1,6-diaminohexane (1,6-DAH), and 1,8-diaminooctane (1,8-DAO). The most popular polyaddition catalysts are 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]-octane (DABCO), dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL), dibutyltin dioctanate (DBTDO), and tin(II) 2-ethylhexanoate (SnOct2).

Figure 1.

Synthesis of biomedical polyurethanes with the prepolymer method.

Figure 2.

Diisocyanates used for the synthesis of biomedical polyurethanes.

Figure 3.

Polyols used for the synthesis of biomedical polyurethanes.

It is also worth mentioning that isocyanate crosslinker molecules contain aromatic phenolic groups (e.g., functionalized catechol, processed lignin, and phenolic compounds from tannin). It was found that some PUs obtained from these substrates do not adversely affect cell proliferation [21].

There are also other less frequently used methods of obtaining PUs, which are discussed later in this article.

BioPUs are biodegradable or non-degradable polymers whose biocompatible characteristics can be tailored to biological systems, such as those of the blood, organs, and tissues, and are biodegradable depending on their components [20]. PUs’ chains comprise relatively long and flexible polyols (soft segments) and a relatively rigid part imparted by chain extenders and ICs (hard segments). PUs are unique polymeric materials with a wide range of physical and chemical properties. The mechanical properties of PUs can easily be modified by altering the soft-to-hard segment ratio and composition [20,22].

The physical properties of BioPUs should be adequate for particular medical applications. Implantology requires materials with optimal yield modulus and strength, along with fatigue, wear, or friction resistance. The modulus, mechanical strength, and fatigue resistance are essential for PUs to be used in reconstructive surgery of soft tissue and cardiovascular. In contrast, the mechanical strength, modulus, and thermal expansion along with conductivity, wear, and abrasion resistance all affect the performance of dental materials. The properties of PUs are usually controlled by the structure, degree of crystallinity, molecular weight, soft-to-hard segment ratio, number of crosslinks, pendant groups, additives, surface properties, etc. All these factors will also affect the PUs’ biocompatibility to some extent [22,23,24,25].

PUs have several properties required from synthetic biomaterials. They can be reproduced as pure materials, fabricated into the desired form without being degraded or adversely changed, and sterilized without changing properties or form. Moreover, PUs have no physical, chemical, or mechanical properties that are adversely altered by the biological environment unless they were purposely designed as degradable materials. PUs also have no adverse effect on the recipient of the implant. These biomaterials have neither induced thrombosis or abnormal intima formation nor interfered with normal clotting mechanisms. PUs do not lead to cell fragility or aging, allergic reactions, hypersensitivity, or carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, or toxic reactions [22,23,24,25].

3. Polyurethane Anti-Cancer Drug Delivery Systems

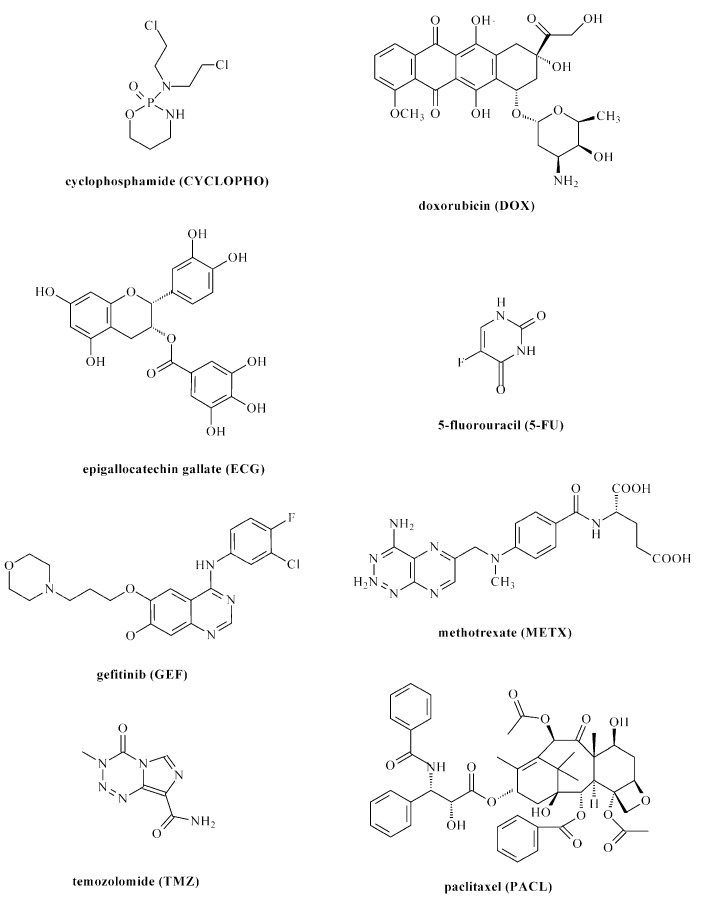

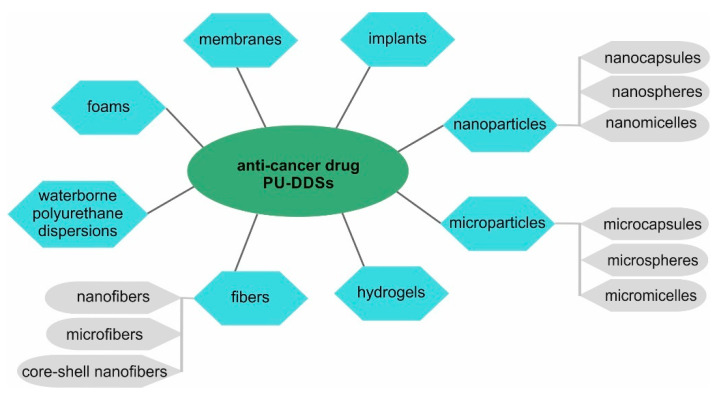

As mentioned earlier, one of the intensively developed directions of pharmacy research is anti-cancer polyurethane DDSs (PU-DDSs). PU-DDSs provide stable formulation, improved pharmacokinetics, and a degree of ‘passive’ or ‘physiological’ targeting to tumor tissue. To date, several kinds of anti-cancer PU-DDSs have been developed [10,13,26]. The developed carriers contain cytostatic drugs such as cyclophosphamide (CYCLOPHO), doxorubicin (DOX), epigallocatechin gallate (ECG), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), gefitinib (GEF), methotrexate (METX), temozolomide (TMZ), and paclitaxel (PACL) (Figure 4). These drugs are commonly known and characterized with different mechanisms of pharmacology actions [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Various types of anti-cancer PU-DDSs have been prepared (Figure 5) (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Anti-cancer drugs used in the technology for polyurethane drug delivery systems.

Figure 5.

Types of polyurethane drug delivery systems for anti-cancer drugs.

Table 1.

Polyurethane drug delivery systems.

| Drug/Drugs | Type of PUs or Composites | Type of DDSs | Main Conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOX | PEG-1500/bis-MPA/IPDI | nano- and microparticles/injectable carriers |

|

[35] |

| DOX | HDI/PCL/PEG | microcapsules |

|

[36] |

| DOX | PU-SS-COOH: PEG-1000/PCL-2000/HDI/CYS/DMPA; PU-SS-COOH-NH2: PEG-1000/PCL-2000/HDI/CYS/DMPA/1,6-diaminohexane | micelles |

|

[37] |

| DOX | LDI/PEG-PU(SS)-PEG/ | micelles |

|

[38] |

| DOX | PHBHx/PEG-2000/PPG-2050/HDI | thermogel |

|

[39] |

| DOX | LDI/mPEG-OH-5000/PCL; PCL obtained form ε-CL to 2,20-dithiodiethanol | micelles |

|

[40] |

| DOX | PTMC-SS-PTMC/CDI/PEOtz-OH | micelles |

|

[41] |

| DOX | HDI/2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl) propionic acid/PEG; amphiphilic PUs with carboxyl pendent groups | nanoparticles |

|

[42] |

| DOX | IPDI/methoxyl-poly(ethylene glycol) (mPEG)/carboxylic acid/piperazine | micelles |

|

[43] |

| DOX | mPEG-5000/HDI/trimethylolpropane/bis(2-hydroxyethyl) disulfide | core-shell nanogels |

|

[44] |

| DOX | poly(2-oxazoline)s/PLA-SS-PLA/LDI | micelles |

|

[45] |

| DOX | PEG-2000/HDI and PCL-2000/PEG-2000/HDI | nanomicelles |

|

[46] |

| DOX | mPEG-1000 (or PEG-2000)/poly(1,3-propylene succinate) diols (PPS)/IPDI | micelles |

|

[47] |

| DOX | PLA-SS-PLA/LDI/PEG | micelles |

|

[48] |

| DOX | WPU/CS | membranes |

|

[49] |

| DOX | mPEG-1900/PCL/LDI; PUs with benzoic-imine linkage | micelles |

|

[50] |

| DOX | polycondensation products of ortho ester-based diols and HDI (or HMDI) | microparticles |

|

[51] |

| DOX | polycondensation product of terephthalilidene-bis(trimethylolethane) and LDI (and next termination process with allyl alcohol) | nanomicelles |

|

[52] |

| DOX |

trans-4,5-dihydroxy-1,2-dithiane (O-DTT)/HDI/mPEG |

nanomicelles |

|

[53] |

| DOX | PEG-2000/bis-1,4-(hydroxyethyl) piperazine (HEP)/O-DTT/HDI | nanomicelles |

|

[54] |

| DOX | LDI/PDO/PEG/PCL/folic acid (FA) | nano- and micelles |

|

[55] |

| DOX | PCL/poly (tetramethylene ether) glycol/HDI | cellulose acetate/PU/carbon nanotubes/composite nanofibers |

|

[56] |

| DOX | LDI/hydrazine/dihydroxy carboxybetaine | conjugates/nano- and micromicelles |

|

[57] |

| DOX | Dipentaerythritol/HDI/mPEG-2000/glycerol | conjugates/nanomicelles/dendritic PU |

|

[58] |

| DOX and PACL | PLA-SS-PLA/IPDI/PEG | micelles |

|

[59] |

| ECG | MEG/BDO/PEG-200/HDI/IPDI | microparticles |

|

[60] |

| 5-FU | HDI/PEG-650 or -1250 or -1500 or -2000/1,2−DAE or 1,6-DAH or 1,4-DAB or 1,8-DAO/L-LYS | WPU |

|

[61] |

| 5-FU and PACL | (PCL/HDI)/PNIPAAm grafted-chitosan core-shell nanofibers | core-shell nanofibers |

|

[62] |

| METX | PCL-b-PEG-b-PCL/BDI/ L-glutathione oxidized |

films |

|

[63] |

| PACL | L-LYS-GQA/L-LYS-ABA-ABA tripeptide/HPCL/HPEG/LDI/PDO | nanomicelles |

|

[64] |

| PACL | PEG-1000/PCL-2000/LDI/BDO/CYS or PEG-1000/PCL-2000/LDI/MDEA/BDO or PEG-1000/PCL-2000/LDI/CYS/MDEA | micelles |

|

[65] |

| PACL | PCL-co-PEG/HMDI | nanoparticles |

|

[66] |

| PACL and TMZ | PU purchased from Lubrizol Co | magnetic particles incorporated into nanofibers |

|

[67] |

| TMZ | PCL/HDI/BDO |

|

|

[68] |

| DOX | polycondensation products of multi-functional L-lysine monomers/1,12-dodecanediol | nanomicelles |

|

[69] |

| GEF | TDI/unknown polyol/unknown cross-linker (Vysera Biomedical Ltd.); GEF-loaded PLGA-based microspheres | PU foams either as micronized drug or as GEF-PLGA microspheres |

|

[70] |

| PACL | MDI/PCL-4000/BDO | membrane |

|

[71] |

| CYCLOPHO | TDI/PEG-600 (or -1500 or -3500)/DEG | implant |

|

[72] |

| DOX | MDI/PPG-N3/PPEG-2000 or PPEG-4000 | micelles |

|

[73] |

| 5-FU | PCL (or PLA, CL/LA copolymers)/HDI | conjugates |

|

[74] |

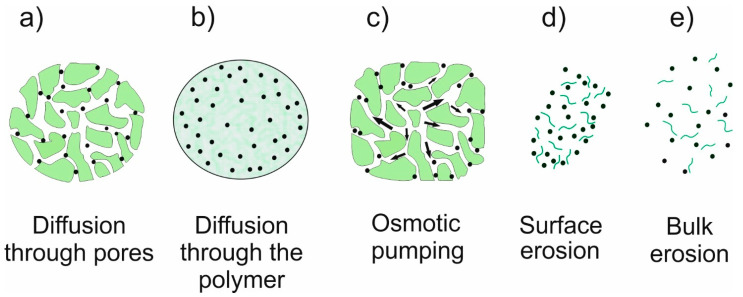

The controlled release of a drug is a crucial property of DDS due to the effectiveness and biosafety of the therapy. Considering the physical and chemical properties of both the drug and the matrix, the mechanisms used are diffusion, erosion, swelling, or osmosis. However, most often a mixed mechanism is used (Figure 6) [6,25]. Diffusion is a concentration-gradient-driven mass transfer process. In a diffusion release system, the drug’s diffusion kinetics is the rate limiting step. In a diffusion-mediated controlled release system, the drug can either be dispersed or dissolved in the polymeric matrix. If the drug is already dissolved in the matrix, it can lead to an initial burst release from the surface. Many factors, such as a change in temperature or pH, the matrix’s composition, and the drug molecule’s size, affect diffusivity [3,4,25]. An eroding polymer matrix is preferred for implantable DDSs. There is no need for DDS retrieval after implantation because the polymeric matrix gets eliminated by erosion. However, the resorbability and toxicity of the degrading products are very important. A drug molecule gets released from DDS only upon the hydrolytic degradation of the matrix. The degradation of DDS depends on the rate of water penetration into the matrix and the kinetics of the hydrolysis process. If water cannot readily penetrate the DDS, surface erosion behavior is observed. Conversely, if water penetrates more rapidly than the degradation rate of the polymeric matrix, bulk erosion is induced. Sometimes degradation products themselves catalyze hydrolysis, leading to autocatalytic degradation [6,25]. Swelling as a drug release mechanism can be used both in polymer matrices and crosslinked polymer networks. The drug is dissolved or dispersed in a matrix with limited diffusivity. Electrostatic and ionic interactions, entropy changes, hydrophilic/hydrophobic interactions, and osmotic stress influence a solvent’s diffusion into the polymer network, leading to solvation and swelling. Generally, the kinetics of drug release from DDSs depends on the surface area and degree of swelling [3,4,25]. Osmosis-mediated controlled DDSs are also used. In osmotic pump-based DDSs, a drug and an osmogen are compacted to form a core compartment, which is enveloped by a semi-permeable membrane. The membrane selectively allows only an inward flow of the solvent under an osmotic gradient. The solvent flow leads to the dissolution of drug molecules, which release out of the system under hydrostatic pressure at a constant rate. However, these systems are highly complicated to fabricate. Moreover, membrane rupture can lead to dose dumping of drugs [4,25].

Figure 6.

The drug release mechanisms involved in different polymeric drug delivery systems.

4. Anti-Cancer Drug Delivery Systems Obtained from Biodegradable Polyurethanes

Biodegradable PU-DDSs can be in the form of nano- or microsystems (micelles, nanoparticles, nanocapsules, microspheres, and pellets), membrane systems (films and foams), or matrix systems (gels and scaffolds) (Table 1). The drug release profiles from these DDSs are often discussed in relation to their composition, swelling, initial drug-loading, and degradation rate. The pH and presence of enzymes are also factors that influence drug release kinetics [26].

Biodegradable PU used in PU-DDSs production can be obtained via polyaddition [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] or the polycondensation process [69]. IPDI, HDI, LDI, CDI, HMDI, and BDI were used as IC components in biodegradable PUs synthesis.

A very interesting group of PU-DDSs are the systems responding to physicochemical and biological stimuli.

One strategy focuses on PU-DDSs’ preparation, which characterizes thermal anti-cancer drug release control [35]. For example, thermoresponsive PU-DDSs’ aqueous media were obtained. By increasing the PEG content, an LCST was manifested that could easily be tuned from 30 °C to 70 °C. PU nanoparticles with lower critical solution temperature (LCST) values below the body temperature and temperature-responsive DOX release were characterized by a highly controlled drug release [35]. The amphiphilic aliphatic PU (APU) nanocarriers showed thermoresponsiveness above lower LCST at 41–43 °C, corresponding to cancer tissue’s temperature [69]. The APUs were obtained from L-lysine monomers and 1,12-dodecanediol via a polycondensation process. The obtained nanoparticles accomplished more than 90% of cell death in breast cancer (MCF 7) cells. Moreover, the PU nanoparticles were readily taken up and internalized in the cancer cells [69]. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate)-based PU thermogels as highly controlled anti-cancer DDSs were also obtained [39]. DTX was released from DDSs with zero-order kinetics for 10 days. DTX-loaded thermogel showed an enhanced anti-melanoma effect on melanoma compared with the free drug and showed no apparent harm to other tissues, including liver, heart, spleen, kidney, and lung tissues [39].

Another strategy is that of pH-stimuli-responsive PU-DDSs [36,47,48,51,52,57]. A very interesting example are PUs obtained from HDI, 2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl) propionic acid, and PEG [42]. An in vitro cellular uptake assay and a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay demonstrated that these DDSs had a higher level of cellular internalization and higher inhibitory effects on the proliferation of human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells than that of pure DOX [42]. Similar DDSs were obtained from IPDI, methoxyl-poly(ethylene glycol) (mPEG), carboxylic acid groups, and piperazine groups. The DDSs released DOX at a controlled rate with a lowering of the pH value [43]. Liu and co-workers obtained pH-stimuli-responsive PU-DDSs (from HDI, PEG, and PCL) characterized by no burst release of DOX [43].

Another way to control the anti-cancer drug release is through redox-sensitive systems [37,45,53,59,65]. Redox-sensitive PU micelles, with tunable surface charge, switch abilities, and crosslinked with pH cleavable Schiff bonds, were obtained. PU micelles with DOX displayed high cytotoxicity against tumor cells [37]. Reduction-responsive micelles based on biodegradable amphiphilic PUs (polyurethane with disulfide bonds and PEG fragments; PEG-PU(SS)-PEG) were obtained by Zhang [38]. Under the influence of the reducing substance glutathione (GSH), the disulfide bond in the main chain broke, triggering the release of the loaded DOX. Cell experiments confirmed that treatment with DOX-loaded PEG-PU(SS)-PEG micelles significantly inhibited the growth of C6 cells compared with that of other groups [38]. GSH-responsive PUs were also described in other papers [44,54]. Similarly, reduction-sensitive PUs were synthesized using a disulfide-containing PCL as the hydrophobic block and a cystamine-functionalized PEG as the hydrophilic block [40]. Under a reductive environment, DOX was released in vitro within 5 h. DOX-loaded PU micelles displayed significant anti-tumor activity [40].

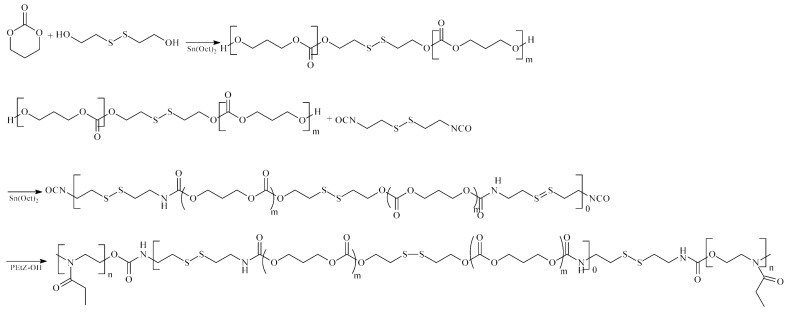

Dual-controlled anti-cancer DDSs were also obtained [41]. One of the more interesting examples of such a system is the pH and redox dual-stimuli-responsive PU micelles prepared from PTMC–SS–PTMC, CDI, and PEOtz–OH (Figure 7). In vitro drug release profiles and cell experiments confirmed that the obtained PU micelles caused controlled DOX release to C6 cells [41]. Another example of a dual system is dendritic PUs synthesized from dipentaerythritol, HDI, mPEG-2000, and glycerol. These obtained PU-DDSs showed excellent pH/ultrasound dual-triggered DOX-release performance [58].

Figure 7.

Synthesis of the pH and redox dual stimuli-responsive polyurethanes.

Composite biodegradable DDSs containing PUs were also obtained [49,56,62,68,74]. Obtained waterborne polyurethane (WPU) and chitosan (CS) composite membranes exhibited fine biodegradability, favorable cytocompatibility, and excellent blood compatibility. A cellular uptake assay and CCK 8 assay showed that the DOX was released efficiently from DDSs and taken up by tumor cells [49]. Another important example of systems of this type of DDSs are the nanofibers from cellulose acetate/PU/carbon nanotubes. The obtained results demonstrated the high effects of DOX-loaded nanofibers on the death of LNCaP prostate cancer cells [56]. Farboudi and co-workers obtained a composite DDS (PCL/HDI/PNIPAAm grafted-chitosan core) containing two cytostatics—5-FU and PACL [62]. The drugs were released from nanofibers under an acidic and physiological pH with high control. There was no burst release of PACL and 5-FU from the nanofibers. Incubation of the nanofibers in 4T1 breast cancer cells indicated the good adhesion of cells to the surface of the nanofibers [62].

Other exciting examples are biodegradable PU-DDSs containing superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPION) [50]. It was found that PU micelles in combination with SPION exhibit excellent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the targeting of DOX to the tumor precisely, leading to a significant inhibition of cancer [50].

In summary, many different biodegradable PU-DDSs (or PU-composite DDSs) have been developed, including those which respond to physicochemical and biological stimuli. Despite this, none of the developed DDSs of this type have been clinically applied yet.

5. Anti-Cancer Drug Delivery Systems Obtained from Non-Biodegradable Polyurethanes

Non-degradable PUs, used in DDSs technology, are mainly characterized by high biostability, good blood or tissue compatibility, and structural and mechanical strength for long- or medium-term use (e.g., dental and orthopedic implants). The release of drugs from non-degradable PU-DDSs depends mainly on diffusion. The release rate is governed by the thickness and permeability of DDS as well as the drug solubility in the polymer matrix [26].

One of the most interesting examples of non-degradable anti-cancer PU-DDSs are PU foams (synthesized from TDI) containing GEF. Drug-release studies showed a sustained highly controlled release of GEF over nine months (with zero-order kinetics). The developed biomaterial is dedicated for the palliative treatment of bronchotracheal cancer [70]. Another fascinating DDS with very high cytostatic (PACL) release control for 10 days is temperature-responsive PUs (obtained from MDI, PCL, and BDO) [71]. The PU membranes were non-cytotoxic to a broad range of cell lines.

However, in some cases, the use of non-biodegradable or semi-biodegradable PU materials may raise some concerns, mainly possible toxicological problems. Semi-biodegradable implants were obtained using TDI, PEG, and DEG, for example [72]. Some of the developed PU-DDSs were characterized by relatively high CYCLOPHO release control (with near zero-order kinetics). However, the authors did not conduct complete toxicological tests of the obtained biomaterials. Similarly, pH-responsive PU micelles were obtained using MDI [73]. The DOX-loaded PU micelles at pH 6.0 DOX were rapidly released. The released DOX exerted potent anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects in vitro. However, the authors did not discuss the possible toxicity of the decomposition products of the obtained PUs. Another interesting example of the PU-DDSs is the dual systems (as carriers of PACL and TMZ) constituting the magnetic metal nanoparticles incorporated into poly(acrylic acid) grafted-CS/PU core-shell nanofibers [67]. The obtained results indicated that the synthesized nanofibers could be used for the targeted delivery of anti-cancer drugs with a maximum apoptosis of 49.6% for U-87 MG glioblastoma cells. However, no complete DDSs biodegradation studies or toxicological tests of the carrier degradation products were performed.

The above systems were obtained by a polyaddition process (prepolymer or one-step method).

6. Anti-Cancer Polyurethane Prodrug

One of the most interesting types of anti-cancer PU-DDSs are macromolecular prodrugs (macromolecular conjugates). Macromolecular prodrugs are a covalent conjugation of a drug with a polymeric chain. As is well-known, many types of labile chemical bonds are formed between a polymer chain and a drug that are susceptible to enzymatic or hydrolytic degradation (e.g., amide, carbonate, ester, ether, and urethane) [4]. Polyurethane prodrugs (PU-prodrugs) can have varied and complex structures. A drug moiety might be a terminal group of the PU chain, linked to the polymer through a pendant group, or it could also be incorporated into the PU backbone [4,26]. The kinetics of drug release from anti-cancer PU-prodrugs depends on the type of linkage between PU and drug molecules, structure, hydrophilic–hydrophobic properties, and the molecular weights or polydispersity of PU. PUs based on polyester segments degrade faster than PU based on polycarbonate or polyether segments, for example [4,10,26]. The selection of these parameters allows short-, medium-, or long-term anti-cancer PU-prodrugs to be obtained.

One example of a very effective anti-cancer PU-DDSs is 5-FU-PU conjugates obtained from HDI, dihydroxy(polyethylene adipate) (OEDA), and homo- or copolymers of LA and CL [74]. The synthesized PU conjugates are an example of DDS where the drug molecules were incorporated into the polymer chain. Drug-release studies showed the sustained release, and in some cases, highly controlled release, of 5-FU over 35 days (with near zero-order kinetics). It was found that the release of 5-FU from PU-DDSs depended on the nature of oligoester units and consisted of soft and hard segments.

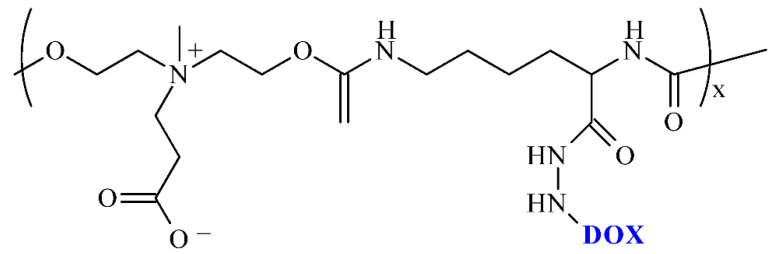

PU conjugates, where molecules of the drug were from the pendant group of the macromolecular chain, were obtained by Qian and co-workers (Figure 8) [57]. The PU-DDSs were obtained from LDI, hydrazine, dihydroxy carboxybetaine, and DOX. The obtained pH-responsive PU-DDSs showed high stability in a physiological environment and continuously released the DOX under acidic conditions. In addition, cytotoxicity studies demonstrated the pure PU carrier to be virtually non-cytotoxic, while the prodrug micelles were more efficient in killing tumor cells.

Figure 8.

Structure conjugates of polyurethane and doxorubicin.

A novel dendritic polyurethane-based prodrug with a drug content of 18.9% was obtained by conjugating DOX onto the end groups of the functionalized dendritic PU via acid-labile imine bonds [58]. The PU-DDSs showed excellent pH/ultrasound dual-triggered drug release performance, with drug leakage of only 4% at pH 7.4 but a cumulative release of 14% and 88% at pH 5.0 without and with ultrasound, respectively. With ultrasound, the PU micelles possessed greater tumor-growth inhibition than that of free DOX, but without ultrasound, they showed no apparent cytotoxicity on the tumor cells.

The use of PU and anti-cancer drugs conjugates may have certain dangers. During the degradation of the conjugates, drug molecules and various oligomeric fragments containing the active substance molecules are formed. This may pose a toxicological risk due to the lack of complete knowledge about the biological properties of the breakdown products of these conjugates.

7. Conclusions, Challenges, and Prospects

According to various global cancer statistics, there were about 20 million new cancer cases and about 10 million deaths last year. Cancer treatment methods include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. Unfortunately, these therapy methods are often limited in many cases of intensely aggressive tumors with a high fatality rate. The attempts to apply polymeric DDSs as a novel and more promising therapy method are increasingly made to improve the cure for and survival rate of cancer patients. DDSs based on PUs have become one of the most interesting directions of research on new anti-cancer drug carriers, further opening a new clinical treatment method for cancer.

What are the main challenges in the technology of new anti-cancer PU-DDSs? Despite intensive research, it has not been possible to resolve the following problems fully:

-

-

some of the PUs (mainly based on aromatic isocyanates), products of their degradation, used solvents, etc., may exhibit toxic, irritating, and allergenic properties.

-

-

PU nano- and microcarriers have an active and large surface and can “negatively” interact with biomolecules.

-

-

The immune system may incorrectly recognize PU-DDSs.

-

-

Nano-PU-DDSs have the size of some proteins and can interfere with the transmission of information between cells.

-

-

A small number of developed PU-DDSs are characterized by a fully controlled release of the anti-cancer drug.

-

-

In many cases, the occurrence of the phenomenon of the drug’s burst release is observed.

-

-

Some methods of obtaining PU-DDSs are multi-stage and complex.

-

-

The cost of raw materials and technologies for obtaining PU-DDSs is, in many cases, high.

Although many developed anti-cancer PU-DDSs have been used in pre-clinical trials, no obtained system has been approved for commercial use. It is worth considering that most of these studies are in early stages, and their clinical effects must be further verified. However, positive and prospective biological and pharmaceutical test results in many cases indicate the need for further work on these types of DDS, and they offer hope for their quick practical application in cancer therapy.

Abbreviations

| APUs | amphiphilic aliphatic polyurethanes |

| BDI | tetramethylene diisocyanate |

| BDO | 1,4-butanediol |

| BioPUs | biomedical PUs |

| CL | ε-caprolactone |

| CYCLOPHO | cyclophosphamide |

| CS | chitosan |

| CYS | Cystaminedihydrochloride |

| CDI | bis(2-isocyanatoethyl) disulfide |

| DABCO | 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]-octane |

| 1,4-DAB | 1,4-diaminobutane |

| 1,2-DAE | 1,2-diaminoethane |

| 1,6-DAH | 1,6-diaminohexane |

| 1,8-DAO | 1,8-diaminooctane |

| DBTDL | dibutyltin dilaurate |

| DBTDO | dibutyltin dioctanate |

| DEG | diethylene glycol |

| DDS/DDSs | drug delivery system(s) |

| DMPA | 2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl)propionic acid |

| DOX | doxorubicin |

| EG | ethylene glycol |

| ECG | epigallocatechin gallate |

| FA | folic acid |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| GG | glycolide |

| GEF | gefitinib |

| GSH | glutathione |

| HDI | hexamethylene diisocyanate |

| HMDI | dicyclohexylmethane 4,4′-diisocyanate |

| HEP | bis-1,4-(hydroxyethyl) piperazine |

| HPEG | hydrazone-ended methoxyl-poly(ethylene glycol) |

| HPCL | hydrazone-embedded poly(ε-caprolactone) diol |

| IC/ICs | diisocyanate/diisocyanates |

| IPDI | isophorone diisocyanate |

| LA | lactide |

| LCST | lower critical solution temperature |

| LDI | L-Lysine diisocyanate ethyl ester |

| L-LYS | L-lysine |

| L-LYS-GQA | L-lysine-derivatized gemini quaternary ammonium salts with two primary amine groups |

| L-LYS-ABA-ABA tripeptide | L-lysine-γ-aminobutyric acid-γ-aminobutyric acid tripeptide |

| mPEG | methoxyl-poly(ethylene glycol) |

| MDEA | N-methyl-diethanolamine |

| MDI | 4,4′-methylenebis(phenyl isocyanate) |

| EG | ethylene glycol |

| METX | Methotrexate |

| bis-MPA | 2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl)-propionic acid |

| NP | nanoparticles |

| O-DTT | trans-4,5-dihydroxy-1,2-dithiane |

| OEDA | dihydroxy(polyethylene adipate) |

| PACL | paclitaxel |

| PBS | phosphate buffered saline |

| PCL | poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| PEG-PU(SS)-PEG | polyurethane with disulfide bonds and PEG fragments |

| PEOtz-OH | poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) |

| PHBHx | poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) |

| PLGA | copolymer of lactide and glycolide |

| PDO | 1,3-propanediol |

| PEG | poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PLA | polylactide |

| PLACL | copolymer of lactide and ε-caprolactone |

| PLA-SS-PLA | PLA with disulfide bonds |

| PNIPAAm-g-chitosan | poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-grafted-chitosan |

| POEUs | poly(ortho ester urethanes) |

| POx | poly(2-oxazoline)s |

| PPG | poly(propylene glycol) |

| PPG-N3 | azide-grafted PEG |

| PPEG | Propargyl-grafted PEG |

| PPS | poly(1,3-propylene succinate) diols |

| PTMC | poly(trimethylene carbonate) |

| PTMC-SS-PTMC | PTMC with disulfide bonds |

| PTMG | poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol |

| PUs | polyurethanes |

| PU-DDSs | polyurethane drug delivery systems |

| PU-Prodrugs | polyurethane prodrugs |

| PU-SS-COOH | polyurethane obtained from PEG-1000, PCL-2000, HDI, CYS and DMPA |

| PU-SS-COOH-NH2 | product of condensation reaction between the PU-SS-COOH and 1,6-diaminohexane |

| ROP | ring-opening polymerization |

| SnOct2 | tin(II) 2-ethylhexanoate |

| SPION | superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles |

| TDI | toluene 2,4-diisocyanate |

| TMC | trimethylene carbonate |

| TMZ | temozolomide |

| WPU | waterborne polyurethane dispersions |

Author Contributions

M.S. and K.K. substantially contributed to conception, design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. M.S. and K.K. accepted the manuscript content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors declare no competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shanthi M. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z., Tan S., Li S., Shen Q., Wang K. Cancer drug delivery in the nano era: An overview and perspectives (Review) Oncol. Rep. 2017;38:611–624. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasiński A., Zielińska-Pisklak M., Oledzka E., Sobczak M. Smart Hydrogels—Synthetic Stimuli-Responsive Antitumor Drug Release Systems. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:4541–4572. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S248987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulas K., Stefanowicz Z., Oledzka E., Sobczak M. Current state of the polymeric delivery systems of fuoroquinolones—A review. J. Control. Release. 2019;294:195–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J.H., Lee S., Kim J.H., Park K., Kim K., Kwon I.C. Polymeric nanomedicine for cancer therapy. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008;33:113–137. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajpai A.K., Shukla S.K., Bhanu S.K., Ankane S. Responsive polymers in controlled drug delivery. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008;33:1088–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai L., Xu J., Yang Z., Tong R., Dong Z., Wang C., Leong K.W. Engineered biomaterials for cancer immunotherapy. MedComm. 2020;1:35–46. doi: 10.1002/mco2.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osi B., Khoder M., Al-Kinani A.A., Alany R.G. Pharmaceutical, biomedical and ophthalmic applications of biodegradable polymers (BDPs): Literature and patent review. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2022;3:341–356. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2022.2055063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajebi S., Nasr S.M., Rabiee N., Bagherzadeh M., Ahmadi S., Rabiee M., Tahriri M., Tayebi L., Hamblin M.R. Bioresorbable composite polymeric materials for tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2021;70:926–940. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2020.1765365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobczak M. Biodegradable polyurethane elastomers for biomedical applications—Synthesis methods and properties. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2015;54:155–172. doi: 10.1080/03602559.2014.955201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobczak M., Dębek C., Goś P. Preparation polyurethanes as potential biomaterials for short-term applications. e-Polymers. 2010;148 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozimek J., Pielichowski K. Recent Advances in Polyurethane/POSS Hybrids for Biomedical Applications. Molecules. 2022;27:40. doi: 10.3390/molecules27010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wendels S., Averous L. Biobased polyurethanes for biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater. 2021;6:1083–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalirajan C., Dukle A., Nathanael A.J., Oh T.-H., Manivasagam G. A Critical Review on Polymeric Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Polymers. 2021;13:3015. doi: 10.3390/polym13173015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman D. Polyurethane and Polyurethane Nanocomposites: Recent Contributions to Medicine. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021;11:8179–8189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Thouas G.A., Chen Q.-Z. Biodegradable soft elastomers: Synthesis/properties of materials and fabrication of scaffolds. RSC Adv. 2012;2:8229–8242. doi: 10.1039/c2ra20736b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taraghi I., Paszkiewicz S., Grebowicz J., Fereidoon A., Roslaniec Z. Nanocomposites of Polymeric Biomaterials Containing Carbonate Groups: An Overview. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2017;302:1700042. doi: 10.1002/mame.201700042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raval N., Maheshwari R., Shukla H., Kalia K., Torchilin V.P., Tekade R.K. Multifunctional polymeric micellar nanomedicine in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2021;126:112186. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shafiq M., Butt M.T.Z., Khan S.M. Synthesis of Mono Ethylene Glycol (MEG)-Based Polyurethane and Effect of Chain Extender on Its Associated Properties. Polymers. 2021;13:3436. doi: 10.3390/polym13193436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung Y.K., Kim S.W. Recent advances in polymeric drug delivery systems. Biomater. Res. 2020;24:12. doi: 10.1186/s40824-020-00190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hai T.A.P., Tessman M., Neelakantan N., Samoylov A.A., Ito Y., Rajput B.S., Pourahmady N., Burkart M.D. Renewable Polyurethanes from Sustainable Biological Precursors. Biomacromolecules. 2021;22:1770–1794. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c01610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farzan A., Borandeh S., Zanjanizadeh Ezazi N., Lipponen S., Santos H.A., Seppälä J. 3D scaffolding of fast photocurable polyurethane for soft tissue engineering by stereolithography: Influence of materials and geometry on growth of fibroblast cells. Eur. Polym. J. 2020;139:109988. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.109988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aduba D.C., Jr., Zhang K., Kanitkar A., Sirrine J.M., Verbridge S.S., Long T.E. Electrospinning of plant oil-based, non-isocyanate polyurethanes for biomedical applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018;135:46464. doi: 10.1002/app.46464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rokicki G., Parzuchowski P.G., Mazurek M. Non-isocyanate polyurethanes: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2015;26:707–761. doi: 10.1002/pat.3522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borandeh S., van Bochove B., Teotia A., Seppälä J. Polymeric drug delivery systems by additive manufacturing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021;173:349–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherng J.Y., Hou T.Y., Shih M.F., Talsma H., Hennink W.E. Polyurethane-based drug delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;450:145–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emadi A., Jones R.J., Brodsky R.A. Cyclophosphamide and cancer: Golden anniversary. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2009;6:638–647. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tacar O., Sriamornsak P., Dass C.R. Doxorubicin: An update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013;65:157–170. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang C.S., Wang X., Lu G., Picinich S.C. Cancer prevention by tea: Animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:429–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan V., Craig A. Retrospective: On Clinical Studies with 5-Fluorouracil. Cancer Res. 2016;76:767–768. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muhsin M., Graham J., Kirkpatrick P. Gefitinib. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:556–557. doi: 10.1038/nrc1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweitzer B.I., Dicker A.D., Bertino J.R. Dihydrofolate reductase as a therapeutic target. FASEB J. 1990;4:2441–2452. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.8.2185970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newlands E., Stevens M., Wedge S., Wheelhouse R., Brock C. Temozolomide: A review of its discovery, chemical properties, pre-clinical development and clinical trials. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1997;23:35–61. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(97)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallego-Jara J., Lozano-Terol G., Sola-Martínez R.A., Cánovas-Díaz M., de Diego Puente T. A compressive review about Taxol®: History and future challenges. Molecules. 2020;25:5986. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sardon H., Tan J.P.K., Chan J.M.W., Mantione D., Mecerreyes D., Hedrick J.L., Yang Y.Y. Thermoresponsive random poly(ether urethanes) with tailorable LCSTs for anticancer drug delivery. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015;36:1761–1767. doi: 10.1002/marc.201500247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niu Y., Stadler F.J., Song J., Chen S., Chen S. Facile fabrication of polyurethane microcapsules carriers for tracing cellular internalization and intracellular pH-triggered drug release. Colloids Surf. B. 2017;153:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao L., Liu C., Qiao Z., Yao Y., Luo J. Reduction responsive and surface charge switchable polyurethane micelles with acid cleavable crosslinks for intracellular drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2018;8:17888–17897. doi: 10.1039/C8RA01581C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang P., Hu J., Bu L., Zhang H., Du B., Zhu C., Li Y. Facile preparation of reduction-responsive micelles based on biodegradable amphiphilic polyurethane with disulfide bonds in the backbone. Polymers. 2019;11:262. doi: 10.3390/polym11020262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang L., Luo Z., Loh X.J., Wu Y.-L., Li Z. PHA-based thermogel as a controlled zero-order chemotherapeutic delivery system for the effective treatment of melanoma. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019;2:3591–3600. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Z., Guo Q., Cai Y., Zhu X., Zhu C., Li Y., Li B. Poly(ethylene glycol)-sheddable reduction-sensitive polyurethane micelles for triggered intracellular drug delivery for osteosarcoma treatment. J. Orthop. Translat. 2020;21:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu K., Liu X., Bu L., Zhang H., Zhu C., Li Y. Stimuli-responsive micelles with detachable poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) shell based on amphiphilic polyurethane for improved intracellular delivery of doxorubicin. Polymers. 2020;12:2642. doi: 10.3390/polym12112642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang D., Zhou Y., Xiang Y., Shu M., Chen H., Yanga B., Liao B.X. Polyurethane/doxorubicin nanoparticles based on electrostatic interactions as pH-sensitive drug delivery carriers. Polym. Int. 2018;67:1186–1193. doi: 10.1002/pi.5618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He W., Zheng X., Zhao Q., Duan L., Lv Q., Gao G.H., Yu S. pH-triggered charge-reversal polyurethane micelles for controlled release of doxorubicin. Macromol. Biosci. 2016;16:925–935. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qi D., Wang J., Qi Y., Wen J., Wei S., Liu D., Yu S. One pot preparation of polyurethane-based GSH-responsive core-shell nanogels for controlled drug delivery. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020;137:48473. doi: 10.1002/app.48473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhanga H., Liua X., Xua K., Dua B., Zhub C., Li Y. Biodegradable polyurethane PMeOx-PU(SS)-PMeOx micelles with redox and pH-sensitivity for efficient delivery of doxorubicin. Eur. Polym. J. 2020;140:110054. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.110054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J., Dai Z., Zhou Y., Tao W., Chen H., Zhao Z., Lia X. Acid-sensitive charge-reversal co-assembled polyurethane nanomicelles as drug delivery carriers. Colloids Surf. B. 2022;209:112203. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luan H., Zhu Y., Wang G. Synthesis, self-assembly, biodegradation and drug delivery of polyurethane copolymers from bio-based poly(1,3-propylene succinate) React. Funct. Polym. 2019;141:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2019.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saeedi S., Omrani I., Bafkary R., Sadeh E., Shendi H.K., Nabid M.R. Facile preparation of biodegradable dual stimuli-responsive micelles from waterborne polyurethane for efficient intracellular drug delivery. New J. Chem. 2019;43:18534–18545. doi: 10.1039/C9NJ03773J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng Z., Zhenga Y., Zhao L., Zhang Z., Suna Y., Qiao K., Xie Y., Wang Y., He W. An ultrasound-controllable release system based on waterborne polyurethane/chitosan membrane for implantable enhanced anticancer therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2019;104:109944. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei J., Shuai X., Wang R., He X., Li Y., Ding M., Li J., Tan H., Fu Q. Clickable and imageable multiblock polymer micelles with magnetically guided and PEG-switched targeting and release property for precise tumor theranosis. Biomaterials. 2017;145:138–153. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu S., Yang G., Wang J., Wang X., Cheng X., Zha Q., Tang R. pH-sensitive poly(ortho ester urethanes) copolymers with controlled degradation kinetic: Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro evaluation as drug carriers. Eur. Polym. J. 2017;95:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang F., Cheng R., Meng F., Deng C., Zhong Z. Micelles based on acid degradable poly(acetal urethane): Preparation, pH-Sensitivity, and triggered intracellular drug release. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:2228–2236. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu S., Ding J., He C., Cao Y., Xu W., Chen X. Disulfide cross-linked polyurethane micelles as a reduction-triggered drug delivery system for cancer therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014;3:752–760. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu S., He C., Lv Q., Sun H., Chen X. pH and reduction dual responsive cross-linked polyurethane micelles as an intracellular drug delivery system. RSC Adv. 2014;4:63070–63078. doi: 10.1039/C4RA14221G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan Z., Yu L., Song N., Zhou L., Li J., Ding M., Tan H., Fu Q. Synthesis and characterization of biodegradable polyurethanes with folate side chains conjugated to hard segments. Polym. Chem. 2014;5:2901–2910. doi: 10.1039/C3PY01340E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alisani R., Rakhshani N., Abolhallaj M., Motevalli F., Abadi P.G., Akrami M., Shahrousvand M., Jazi F.S., Irani M. Adsorption, and controlled release of doxorubicin from cellulose acetate/polyurethane/multi-walled carbon nanotubes composite nanofibers. Nanotechnology. 2022;33:155102. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ac467b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He Q., Yan R., Hou W., Wang H., Tian Y. A pH-responsive zwitterionic polyurethane prodrug as drug delivery system for enhanced cancer therapy. Molecules. 2021;26:5274. doi: 10.3390/molecules26175274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen W., Liu P. Dendritic polyurethane-based prodrug as unimolecular micelles for precise ultrasound-activated localized drug delivery. Mater. Today Chem. 2022;24:100819. doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.100819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu C., Tan X., Xu Z., Zhu G., Teng W., Zhao Q., Liang Z., Wu Z., Xiong D. Smart drug carrier based on polyurethane material for enhanced and controlled DOX release triggered by redox stimulus. React. Funct. Polym. 2020;148:104507. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2020.104507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marin A., Marin M.A., Ene I., Poenaru M. Polyurethane structures used as a drug carrier for epigallocatechin gallate. Mater. Plast. 2021;58:210–217. doi: 10.37358/MP.21.1.5460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bahadur A., Shoaib M., Iqba S., Saeed A., Saif ur Rahman M., Channar P.A. Regulating the anticancer drug release rate by controlling the composition of waterborne polyurethane. React. Funct. Polym. 2018;131:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2018.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farboudi A., Nouri A., Shirinzad S., Sojoudi P., Davaran S., Akrami M., Irani M. Synthesis of magnetic gold coated poly(ε-caprolactonediol) based polyurethane/poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-grafted chitosan core-shell nanofibers for controlled release of paclitaxel and 5-FU. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;150:1130–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palumbo F.S., Federico S., Pitarresi G., Fiorica C., Giammona G. Synthesis and characterization of redox-sensitive polyurethanes based on L-glutathione oxidized and poly(ether ester) triblock copolymers. React. Funct. Polym. 2021;166:104986. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2021.104986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ding M., Song N., He X., Li J., Zhou L., Tan H., Fu Q., Gu Q. Toward the next-generation nanomedicines: Design of multifunctional multiblock polyurethanes for effective cancer treatment. ACS Nano. 2013;7:1918–1928. doi: 10.1021/nn4002769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guan Y., Su Y., Zhao L., Meng F., Wang Q., Yao Y., Luo J. Biodegradable polyurethane micelles with pH and reduction responsive properties for intracellular drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;75:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piras A.M., Sandreschi S., Malliappan S.P., Dash M., Bartoli C., Dinucci D., Guarna F., Ammannati E., Masa M., Múcková M., et al. Surface decorated poly(ester-ether-urethane)s nanoparticles: A versatile approach towards clinical translation. Int. J. Pharm. 2014;475:523–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bazzazzadeha A., Dizajia B.F., Kianinejadb N., Nouric A., Irani M. Fabrication of poly(acrylic acid) grafted-chitosan/polyurethane/magnetic MIL-53 metal organic framework composite core-shell nanofibers for codelivery of temozolomide and paclitaxel against glioblastoma cancer cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;587:119674. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Irani M., Sadeghi G.M.M., Haririan I. A novel biocompatible drug delivery system of chitosan/temozolomide nanoparticles loaded PCL-PU nanofibers for sustained delivery of temozolomide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;97:744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joshi D.C., Saxena S., Jayakannan M. Development of L-lysine based biodegradable polyurethanes and their dual-responsive amphiphilic nanocarriers for drug delivery to cancer cells. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019;1:1866–1880. doi: 10.1021/acsapm.9b00413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen W., di Carlo C., Devery D., McGrath D.J., McHugh P.E., Kleinsteinberg K., Jockenhoevel S., Hennink W.E., Kok R.J. Fabrication and characterization of gefitinib-releasing polyurethane foam as a coating for drug-eluting stent in the treatment of bronchotracheal cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;548:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen Y., Wang R., Zhou J., Fan H., Shi B. On-demand drug delivery from temperature-responsive polyurethane membrane. React. Funct. Polym. 2011;71:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2011.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iskakov R., Batyrbekov E.O., Leonova M.B., Zhubanov B.A. Preparation and release profiles of cyclophosphamide from segmented polyurethanes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000;75:35–43. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(20000103)75:1<35::AID-APP5>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liao Z.-S., Huang S.-Y., Huang J.-J., Chen J.-K., Lee A.-W., Lai J.-Y., Lee D.-J., Cheng C.-C. Self-assembled pH-responsive polymeric micelles for highly efficient, noncytotoxic delivery of doxorubicin chemotherapy to inhibit macrophage activation: In vitro investigation. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:2772–2781. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sobczak M., Hajdaniak M., Gos P., Oledzka E., Kolodziejski W.L. Use of aliphatic poly(amide urethane)s for the controlled release of 5-fluorouracil. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:914–918. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.