This cohort study analyzes data from US residents to examine the mental health effect of everyday discrimination during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Points

Question

How did everyday discrimination affect mental health during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals residing in the United States?

Findings

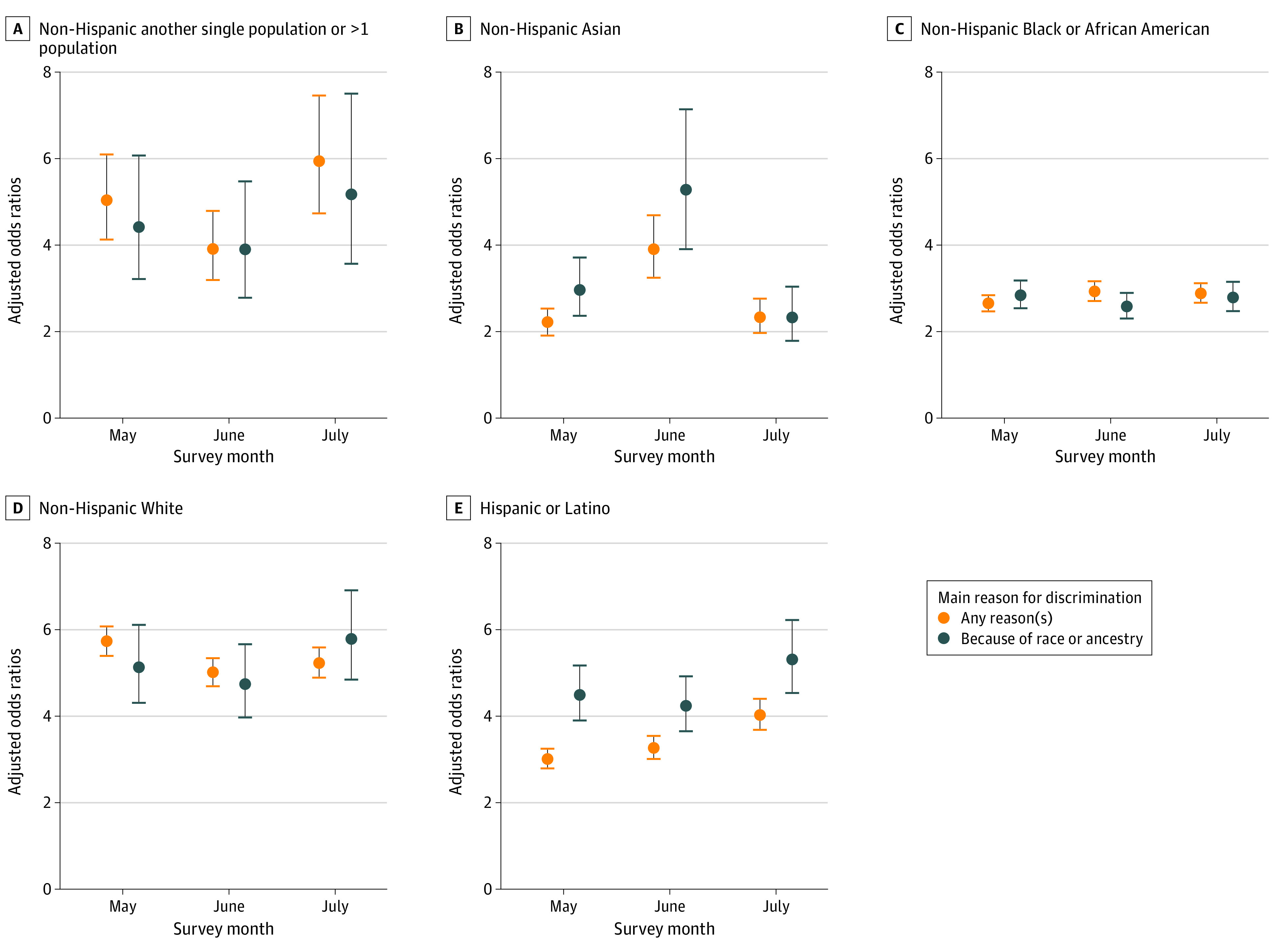

In this cohort study, everyday discrimination was associated with significantly increased odds of moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation between May and July 2020. Notably, this association was stronger among participants self-identifying as Hispanic or Latino or non-Hispanic Asian when the main reason for discrimination was race, ancestry, or national origins.

Meaning

Our findings suggest everyday discrimination linked to race, ancestry, or national origins as a possible contributor to the significant toll on mental health and well-being of Hispanic or Latino or non-Hispanic Asian individuals during the early phase of the pandemic.

Abstract

Importance

The COVID-19 pandemic has coincided with an increase in depressive symptoms as well as a growing awareness of health inequities and structural racism in the United States.

Objective

To examine the association of mental health with everyday discrimination during the pandemic in a large and diverse cohort of the All of Us Research Program.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Using repeated assessments in the early months of the pandemic, mixed-effects models were fitted to assess the associations of discrimination with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, and inverse probability weights were applied to account for nonrandom probabilities of completing the voluntary survey.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The exposure and outcome measures were ascertained using the Everyday Discrimination Scale and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), respectively. Scores for PHQ-9 that were greater than or equal to 10 were classified as moderate to severe depressive symptoms, and any positive response to the ninth item of the PHQ-9 scale was considered as presenting suicidal ideation.

Results

A total of 62 651 individuals (mean [SD] age, 59.3 [15.9] years; female sex at birth, 41 084 [65.6%]) completed at least 1 assessment between May and July 2020. An association with significantly increased likelihood of moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation was observed as the levels of discrimination increased. There was a dose-response association, with 17.68-fold (95% CI, 13.49-23.17; P < .001) and 10.76-fold (95% CI, 7.82-14.80; P < .001) increases in the odds of moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, respectively, on experiencing discrimination more than once a week. In addition, the association with depressive symptoms was greater when the main reason for discrimination was race, ancestry, or national origins among Hispanic or Latino participants at all 3 time points and among non-Hispanic Asian participants in May and June 2020. Furthermore, high levels of discrimination were as strongly associated with moderate to severe depressive symptoms as was history of prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this large and diverse sample, increased levels of discrimination were associated with higher odds of experiencing moderate to severe depressive symptoms. This association was particularly evident when the main reason for discrimination was race, ancestry, or national origins among Hispanic or Latino participants and, early in the pandemic, among non-Hispanic Asian participants.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have far-reaching health1 and economic consequences for the US public, particularly for communities that face structural racism,2 such as American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Hispanic or Latino, and Pacific Islander populations. During the pandemic, these communities have experienced higher rates of unemployment and food and housing insecurity than other groups.3,4,5 These challenges were compounded by the social, political, and economic trauma experienced at the height of the pandemic.6,7

An increase in racially motivated attacks targeting Asian American and Pacific Islander individuals has been reported across the United States; this may be related to the ethnically biased misrepresentations of the origins of COVID-19 across social media platforms.8 For example, studies9,10,11 have reported an increase in online hatred and racially motivated posts toward Asian American communities after the former president of the United States referred to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” in March 2020. In a national, multilingual survey of Asian American and Pacific Islander individuals, more than 60% reported experiencing discrimination during the pandemic.12 Stop AAPI Hate, a national coalition that has collected data on racially motivated attacks related to the COVID-19 pandemic, received more than 109 000 anti-Asian incident reports from March 19, 2020, to December 31, 2021.13 Their recent mental health report14 also revealed adverse mental health consequences of anti-Asian racism, which manifested in many different forms: stress, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Before the pandemic, African American individuals were already experiencing limited health insurance coverage, reduced access to health care, and poor health outcomes.15,16 These long-standing health inequities have been further amplified over the course of the pandemic in association with higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death,17,18 coupled with a sharp rise in unemployment and wage loss due to the pandemic.19 Furthermore, the killing of Black men and women, including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, spotlighted structural racism, systemic inequities, and experiences of discrimination due to race and ethnicity.20

An individual’s experience of discrimination has been reported to have an adverse effect on both physical and mental health among Asian, Black, and Hispanic or Latino adults.21,22,23,24 In a study combining 2 nationally representative surveys,25 Afro-Caribbean American participants (including Haitian, Jamaican, and Trinidadian/Tobagonian individuals) reported the highest rates of discrimination relative to other ethnic subgroups examined in this study. However, participants self-identifying as Asian (including Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese) and Latino American (including Cuban, Mexican, and Portuguese) were most likely to experience harmful psychological consequences in response to discrimination.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the likelihood of having moderate to severe depressive symptoms and/or suicidal ideation would be associated with increasing levels of everyday discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic. We additionally examined factors that may modify this association, such as the main reason for discrimination, survey timing, self-reported race and ethnicity, and prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis. Lastly, we investigated whether associations between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms would vary by survey timing and main reason for discrimination within and across 5 subgroups of self-reported race and ethnicity.

Methods

Study Sample

The institutional review board of the All of Us Research Program approved all study procedures, and all participants provided informed consent to share electronic health records, surveys, and other study data with qualified investigators for broad-based research.

The All of Us Research Program presented racial and ethnic categories as separate questions and allowed participants to select multiple racial and ethnic categories, in accordance with the Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity.26 We relied on these self-reported categories for our analyses, although we recognize that they may not optimally capture the full spectrum of heterogeneity in identity. In this study, participants were initially categorized as Hispanic Asian, Hispanic Black, Hispanic another single population or more than 1 population, Hispanic race not indicated, Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Asian (hereafter referred to as Asian), non-Hispanic Black or African American (hereafter referred to as Black or African American), non-Hispanic another single population or more than 1 population, or non-Hispanic White (hereafter referred to as White) (Table 1 and eTables 1 and 2 and eFigure 1A in the Supplement). We excluded individuals who skipped or preferred not to answer these questions or responded that none of the provided options fully describe them. However, in the mixed-effects modeling analysis, the 5 Hispanic or Latino subgroups were collapsed due to issues with model convergence.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Overall All of Us Research Program Cohort and COPE Survey Respondents.

| Variable | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall AoU cohort (n = 314 994) | COPE respondents (n = 62 651) | |

| Categorical variables | ||

| Sex assigned at birth | ||

| Male | 119 750 (38.0) | 21 158 (33.8) |

| Female | 191 114 (60.7) | 41 084 (65.6) |

| Not male, not female; I prefer not to answer or skipped; no matching concept | 4130 (1.3) | 409 (0.7) |

| Self-reported race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latinoa | ||

| Another single population or >1 population | 834 (0.3) | 119 (0.2) |

| Asian | 286 (0.1) | 35 (0.1) |

| Black | 1158 (0.4) | 75 (0.1) |

| Race not indicated | 52 418 (16.6) | 3071 (4.9) |

| White | 4587 (1.5) | 887 (1.4) |

| Non-Hispanic | ||

| Another single population or >1 population | 7077 (2.2) | 1258 (2.0) |

| Asian | 10 276 (3.3) | 1778 (2.8) |

| Black or African American | 66 954 (21.3) | 3495 (5.6) |

| White | 162 330 (51.5) | 50 705 (80.9) |

| I prefer not to answer; skipped; none of these | 9074 (2.9) | 1228 (2.0) |

| Born in the United States | 262 791 (83.4) | 56 645 (90.4) |

| Employed | 149 504 (47.5) | 34 195 (54.6) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Less than college | 100 545 (31.9) | 4822 (7.7) |

| College or higher | 214 449 (68.1) | 57 829 (92.3) |

| Health insurance | 283 089 (89.9) | 61 039 (97.4) |

| Owned a home | 136 530 (43.3) | 43 583 (69.6) |

| Married/partnered | 150 766 (47.9) | 39 723 (63.4) |

| Prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis | 20 560 (6.5) | 3525 (5.6) |

| Continuous variables | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 54.3 (16.8) | 59.3 (15.9) |

| No. of co-resident, mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.8) |

| Income, mean (SD), $ | 59 933 (55 645.2) | 93 684 (58 625.0) |

Abbreviations: AoU, All of Us Research Program; COPE, COVID-19 Participant Experience.

In the mixed-effects modeling analysis, the 5 Hispanic or Latino subgroups were collapsed due to issues with model convergence.

COVID-19 Participant Experience Survey

The COVID-19 Participant Experience (COPE) survey26 is a brief online survey administered to a subset of participants from the All of Us Research Program27 (hereafter, AoU) to seek new insights into whether and how the pandemic affects people differently over time, starting in May 2020 (eMethods in the Supplement). The survey includes questions on COVID-19 symptoms, physical and mental health, social distancing, economic effects, and coping strategies. At the time of analysis, 62 651 participants had completed at least 1 of the 3 COPE surveys administered in May, June, or July 2020, resulting in an overall participation rate of 19.9% (May, 13.6%; June, 10.4%; July, 9.2%). After excluding 149 participants with missing information on discrimination, we fit mixed-effects logistic regression models using 158 326 COPE surveys completed by 62 502 participants remaining in the study sample.

Exposure

The primary exposure was the level of everyday discrimination assessed using the Everyday Discrimination Scale,21 a 9-item checklist that measures the last month’s experience of discrimination (eg, being treated with less courtesy or respect, being considered as dishonest or threatening) with a 4-point Likert scale response format (from 0 = never to 3 = almost every day). The scale is scored by summing the responses across all items (resulting in total scores from 9 to 36). We then transformed scores to a mean item score by dividing the sum by number of completed items (95%-96% of COPE respondents completed the full scale each month) and created an ordinal version of the exposure variable by rounding the mean score.

At the end of the Everyday Discrimination Scale, there is a follow-up question: “What do you think is the main reason for these experiences? Select all that apply.” We conducted a secondary analysis comparing respondents who reported discrimination solely due to race, ancestry, or national origins with respondents reporting no discrimination (n = 42 006 respondents).

Outcome

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),28 a checklist that scores each of the 9 DSM-IV criteria for depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks using a 4-point Likert scale response format (from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The scale is scored by summing responses to all 9 items, with total scores from 0 to 27; total scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent cut points for mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depressive symptoms28,29 (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Here, we refer to scores of 10 or above as presenting moderate to severe depressive symptoms. In addition to the total scores, we separately examined the ninth item of PHQ-9, which evaluates thoughts of death or self-injury within the last 2 weeks; any positive (nonzero) response to this item was considered a positive indicator for suicidal ideation.

Covariates

Regression models were adjusted for potential confounding factors, including sex assigned at birth, current age, homeownership, employment status, educational attainment, health insurance status, COVID-19 or flulike symptoms in the past month, and self-reported race and ethnicity. Additionally, we tested for potential variations by survey timing, self-reported race and ethnicity, and prepandemic mood disorder (the eMethods in the Supplement describe the case ascertainment strategy).

Statistical Analysis

Mixed-Effects Modeling

As noted, the COPE survey was administered to participants multiple times during the pandemic, although not all respondents completed each monthly survey. To accommodate both missing responses and the correlated nature of repeated measurements,30 we fitted mixed-effects logistic regression models to determine the associations between the repeated measures with participant-specific random intercepts and fixed effects for the timing of survey administration.31 In addition to estimating odds ratios, we obtained and visualized predicted probabilities of having moderate to severe depressive symptoms estimated at specific levels of discrimination.32

Lagged Analysis

To overcome the limitation that our primary exposure and outcome variables were measured concurrently, we additionally tested whether everyday discrimination measured in May 2020 was associated with depressive symptoms measured in June or July 2020. In this analysis, we removed participants who had moderate to severe depressive symptoms in May to minimize the possibility of reverse causation (eg, if depressed individuals are more likely than nondepressed individuals to report discrimination).

Inverse Probability Weighting

It has been previously reported that research volunteers tend to be healthier and have higher socioeconomic status compared with the underlying general population.33 To address this possible healthy volunteer bias among the COPE respondents, we first compared the distribution of sociodemographic covariates between our study sample against the overall AoU cohort. We calculated predicted probabilities of survey completion for each month by fitting 3 separate logistic regression models with sex assigned at birth, self-reported race and ethnicity, birthplace, college education, marital/partnership status, health insurance status, employment status, homeownership, and current age as predictors. We then applied the inverse of the product of predicted probabilities to mixed-effects models.

All analyses in the current study were performed using data from the All of Us Registered Tier Version R2020Q4R2 on the Researcher Workbench, a cloud-based platform where approved researchers can access and analyze data.34 We used R version 4.1.0 in a Jupyter Notebook contained in the Workbench to query data and perform statistical analyses. In all analyses, a 2-tailed value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

As shown in Table 1, COPE respondents (n = 62 651) were more likely to be female (41 084 [65.6%] vs 191 114 [60.7%]), non-Hispanic White (50 705 [80.9%] vs 162 330 [51.5%]), and older (mean [SD] age, 59.3 [15.9] years vs 54.3 [16.8] years) compared with the underlying AoU population (n = 314 994). They were also more likely to have received a college education or more, own a home, have a partner, and have a higher annual household income. In addition, the prevalence of prepandemic mood disorder was lower in the study sample compared with the underlying AoU cohort (3525 [5.6%] vs 20 560 [6.5%]) (eTable 1 in the Supplement shows results stratified by self-reported race and ethnicity).

In addition, the distribution of mean scores on the Everyday Discrimination Scale and the main reason for discrimination varied substantially by survey timing and self-reported race and ethnicity. Perhaps reflecting the concurrent sociopolitical circumstances in the United States, Hispanic Black participants reported the highest levels of discrimination, especially in June 2020, followed by participants self-identifying as Black or African American (eFigure 1A and eTable 2 in the Supplement). We also found substantial variations in the main reason for discrimination by self-reported race and ethnicity (eFigure 1B in the Supplement). While age and gender were most frequently reported as the main reason for discrimination by White participants, ancestry or national origins and race were most frequently reported by Asian and Black or African American participants but least likely to be reported by White participants.

Lastly, the overall prevalence estimates of moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation were highest in May 2020 (13 036 [20.5%] and 4991 [7.9%], respectively), but relatively stable in June and July (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression Analysis

We observed significantly increased likelihood of moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation as the levels of everyday discrimination increased (Figure 1). As shown in Table 2, those who reported discrimination a few times a month and at least once a week over the past month had up to a 3-fold and 10-fold increase, respectively, in the odds of moderate to severe depressive symptoms. This dose-response association is also apparent among participants experiencing discrimination more than once a week in the increases in the odds of moderate to severe depressive symptoms (odds ratio, 17.68; 95% CI, 13.49-23.17; P < .001) and suicidal ideation (odds ratio, 10.76; 95% CI, 7.82-14.80; P < .001). Everyday discrimination was less strongly but still significantly associated with suicidal ideation, and the associations with depressive symptoms were stronger when the main reason for discrimination was race, ancestry, or national origins. In these models, history of COVID-19 symptoms was not associated with either moderate to severe depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation.

Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities of Moderate to Severe Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation According to Level of Everyday Discrimination.

Scores for the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) that were greater than or equal to 10 were classified as moderate to severe depressive symptoms. Any positive response to the ninth item of the PHQ-9, which evaluates thoughts of death or self-injury within the last 2 weeks, was considered a positive indicator for suicidal ideation.

Table 2. Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression Analysis of the Associations of Everyday Discrimination With Moderate to Severe Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation, With Further Variations by Reason for Discriminationa.

| Reported discrimination | Moderate to severe depressive symptomsb | Suicidal ideationc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any reason | Race, ancestry, or national origins | Any reason | Race, ancestry, or national origins | |

| Frequency of reported discrimination, OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Never | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| A few times a month | 2.90 (2.67-3.14)d | 2.54 (2.28-2.84)d | 2.25 (1.99-2.55)d | 2.06 (1.75-2.43)d |

| At least once a week | 9.49 (8.22-10.95)d | 10.14 (8.12-12.65)d | 8.21 (6.84-9.86)d | 11.26 (8.51-14.89)d |

| More than once a week | 17.68 (13.49-23.17)d | 23.09 (14.98-35.60)d | 10.76 (7.82-14.80)d | 7.53 (4.55-12.45)d |

| No. of observations | 158 326 | 68 927 | 158 326 | 68 927 |

| No. of respondents | 62 502 | 42 006 | 62 502 | 42 006 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

We grouped together all respondents with “no discrimination” and grouped the others in an ordinal fashion using a rounded form of the item means on the Everyday Discrimination Scale.

PHQ-9 score ≥10.

Any positive response to the ninth item of the PHQ-9, which evaluates thoughts of death or self-injury within the last 2 weeks, was considered a positive indicator for suicidal ideation.

P < .001.

In the lagged analysis, examining the association of discrimination reported in May 2020 with depressive symptoms in June or July, we found evidence consistent with the findings of the mixed-effects model analyses (Table 3). Participants who reported discrimination due to race, ancestry, or national origins a few times in the past month were 71% (95% CI, 1.23-2.38) and 64% (95% CI, 1.24-2.11) more likely to develop moderate to severe depressive symptoms in the succeeding 1- or 2-month periods, respectively. The odds increased up to 3-fold among those reporting this type of discrimination at least once a week or more than once a week in the past month.

Table 3. Lagged Analysis Examining the Association Between Everyday Discrimination Due to Race, Ancestry, or National Origins in May 2020 and Onset of Moderate to Severe Depressive Symptoms in the Succeeding 1- or 2-Month Periodsa.

| Reported discrimination | Timing of outcome ascertainment in 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| June | June or July | |

| Frequency of reported discrimination, OR (95% CI) | ||

| A few times a month | 1.71 (1.24-2.38)b | 1.64 (1.27-2.12)c |

| At least once a week or more than once a weekd | 2.76 (1.18-6.48)e | 2.93 (1.50-5.70)b |

| No. of respondents | 9995 | 12 943 |

We grouped together all respondents with “no discrimination” and grouped the others in an ordinal fashion using a rounded form of the item means on the Everyday Discrimination Scale.

P < .01.

P < .001.

These 2 exposure categories were combined because of a limited sample size in the lagged analysis.

P < .05.

After the addition of a discrimination × survey timing interaction term, we saw an attenuation of the discrimination-depressive symptoms association over the course of the survey period (interaction P < .001) (eTable 4 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Subsequently, we conducted stratified analyses to estimate the main effect of discrimination and interaction with survey timing within and across the 5 subgroups of self-reported race and ethnicity (Figure 2). Among Hispanic or Latino participants, the association between everyday discrimination and moderate to severe depressive symptoms was consistently larger in magnitude when the main reason for discrimination was race, ancestry, or national origins compared with other types of discrimination; the association was strongest in June 2020 among Asian participants. However, we found no such variations by survey timing or main reason for discrimination in other groups.

Figure 2. Main Association of Everyday Discrimination With Moderate to Severe Depressive Symptoms and Interaction With Survey Timing Within and Across Subgroups of Self-reported Race and Ethnicity.

Interestingly, the sign of a discrimination × prepandemic mood disorder interaction was also negative (interaction P < .001) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). As exposure to everyday discrimination increased, the association between prepandemic mood disorder and depressive symptoms became less pronounced. As illustrated in eFigure 3 in the Supplement, high levels of everyday discrimination were as strongly associated with moderate to severe depressive symptoms as was a history of prepandemic mood disorder.

Discussion

Everyday discrimination has been implicated as a strong risk factor for adverse mental health outcomes. We leveraged a large and diverse cohort, derived from the All of Us Research Program, to examine the time-varying associations of everyday discrimination with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation and factors potentially modifying this association. First, we observed significant associations of discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Next, stratified analyses in subgroups defined by self-reported race and ethnicity revealed variations in this association based on the main reason for discrimination and survey timing. The association between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms was particularly evident when the main reason for discrimination was race, ancestry, or national origins among Hispanic or Latino participants and, early in the pandemic, among those self-identifying as non-Hispanic Asian.

Our study adds to prior work implicating adverse mental health outcomes resulting from racial discrimination in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lee and Waters35 examined the associations of racial discrimination with mental, physical, and sleep health problems during the first months of the pandemic in a sample of 410 adults self-identifying as Asian and currently residing in the United States. The participants experienced a nearly 30% increase in racial discrimination of various forms (eg, hate crimes, microaggressions, vicarious discrimination), which was significantly associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms. In a larger cross-sectional study that included both Asian and Black American adults, Chae and colleagues36 focused specifically on experiences of vicarious racism, defined as hearing about or seeing racist acts directed against members of one’s racial group, and vigilance about racial discrimination. Increasing exposure to vicarious racism and racial discrimination vigilance was associated with more symptoms of depression and anxiety, although the study did not assess clinically significant depression.

Wu and colleagues37 examined COVID-19–related discrimination using repeated measurements from Asian and White individuals (N = 7778) who participated in more than 13 waves of an internet panel tracking survey between March 10, 2020, and September 30, 2020. They further differentiated Asian participants who were born in the United States from those born outside the United States. Relative to White participants, both Asian American and Asian immigrant participants were more likely to report depressive symptoms (measured using the PHQ-4 scale). Within the Asian sample, Asian immigrant participants reported higher levels of acute discrimination in March 2020, whereas Asian American participants reported significantly higher levels of discrimination in April and early May of 2020.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths relative to prior reports. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most diverse study conducted in the United States examining the mental health effect of everyday discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic. We leveraged repeated measurements of discrimination and depressive symptoms and examined temporal fluctuations within and across 5 subgroups defined based on self-reported race and ethnicity. We further included COVID-19 symptoms as a covariate in our adjusted models to remove potential confounding of the hypothesized association between discrimination and mental health outcomes by COVID-19 infection. In addition, because the COPE respondent sample may not have been fully representative of the larger All of Us cohort, we applied inverse probability weighting to minimize selection bias. Lastly, we leveraged linked electronic health records to examine potential effect modification of the impact of discrimination by preexisting mood disorder.

Our study should also be evaluated in light of several limitations. First, the first COPE survey was administered in May 2020, after the start of the pandemic. Because we did not have prepandemic measurements of discrimination or PHQ-9 scores, we could not capture the evolution of their relationship at the very beginning of the pandemic. Second, the mixed-effects regression analysis could not establish a causal relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms because these were measured concurrently during waves of the survey. However, we also conducted a lagged analysis and found evidence suggesting that discrimination due to race, ancestry, or national origins was associated with subsequent depressive symptoms. Third, while our use of inverse probability weighting should address discrepancies between COPE respondents and the overall AoU cohort, it would not account for selection bias arising from covariates not included in the weight model or those unmeasured. Furthermore, the generalizability of these findings warrants caution because the AoU cohort is not a fully representative sample of the US population. For example, the COPE survey was administered online in English or Spanish, potentially underrepresenting participants with limited digital access or proficiency in those languages. Lastly, the current study does not account for regional variation in levels of discrimination and COVID-19 infection rates or heterogeneity within subgroups of self-reported race and ethnicity. Future studies are needed to examine how these contextual factors may affect the relationship between discrimination and mental health.

Conclusions

In a large-scale, longitudinal investigation of the effect of COVID-19 on mental health and well-being, we find that everyday discrimination was significantly associated with both depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. We found further variations in these associations when stratified by survey timing and self-reported race and ethnicity. In addition, at elevated levels of discrimination, the likelihood of having moderate to severe depressive symptoms was similar among those with and without a prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis. By demonstrating the complex and dynamic relationship between discrimination and adverse mental health outcomes in a large and diverse sample of the United States, this study provides empirical evidence regarding the adverse mental health consequences of discrimination based on race, ancestry, or national origins during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among individuals self-identifying as Hispanic or Latino or non-Hispanic Asian.

eTable 1. Comparison of sociodemographic characteristics among the COPE respondents (Nrespondent = 62,651), stratified by self-reported race and ethnicity

eTable 2. Distribution of the mean ratings on the Everyday Discrimination Scale by survey timing and self-reported race and ethnicity

eTable 3. Distribution of depressive symptom severity (based on the PHQ-9 score) by survey timing

eTable 4. Variations in the associations of everyday with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by the main reason for discrimination and survey timing

eTable 5. Variations in the associations of everyday discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by the main reason for discrimination and prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis

eFigure 1. Distribution of the mean item score on the Everyday Discrimination Scale among participants who reported everyday discrimination (Nrespondent = 35,844), stratified by survey timing and self-reported race and ethnicity

eFigure 2. Variations in the associations of everyday discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by survey timing, estimated from mixed-effects models

eFigure 3. Variations in the associations of everyday discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis, estimated from mixed effect models

eMethods

eReferences

References

- 1.Mude W, Oguoma VM, Nyanhanda T, Mwanri L, Njue C. Racial disparities in COVID-19 pandemic cases, hospitalisations, and deaths: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:05015. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DR, Cooper LA. COVID-19 and health equity: a new kind of “herd immunity.” JAMA. 2020;323(24):2478-2480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Getachew Y, Zephyrin L, Abrams MK, Shah A, Lewis C, Doty MM. Beyond the case count: the wide-ranging disparities of COVID-19 in the United States. The Commonwealth Fund. Published September 10, 2020. Accessed October 26, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/sep/beyond-case-count-disparities-covid-19-united-states

- 4.Wolfson JA, Leung CW. Food insecurity and COVID-19: disparities in early effects for US adults. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):E1648. doi: 10.3390/nu12061648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yip SW, Jordan A, Kohler RJ, Holmes A, Bzdok D. Multivariate, transgenerational associations of the COVID-19 pandemic across minoritized and marginalized communities. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(4):350-358. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novacek DM, Hampton-Anderson JN, Ebor MT, Loeb TB, Wyatt GE. Mental health ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Black Americans: clinical and research recommendations. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(5):449-451. doi: 10.1037/tra0000796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz NG, Horowitz JM, Tamir C. Many Black, Asian Americans say they have experienced discrimination amid coronavirus. Pew Research Center. Published July 1, 2020. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/07/01/many-black-and-asian-americans-say-they-have-experienced-discrimination-amid-the-covid-19-outbreak/

- 8.Covid-19 fueling anti-Asian racism and xenophobia worldwide. Published May 12, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide

- 9.Hswen Y, Xu X, Hing A, Hawkins JB, Brownstein JS, Gee GC. Association of "#covid19" versus "#chinesevirus" with anti-Asian sentiments on Twitter: March 9-23, 2020. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(5):956-964. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P, Catalano T. Social media, right-wing populism, and COVID-19: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of reactions to the “Chinese Virus” discourse. In: Musolff A, Breeze R, Kondo K, eds. Pandemic and Crisis Discourse. Bloomsbury Publishing; 2022. doi: 10.5040/9781350232730.ch-018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darling-Hammond S, Michaels EK, Allen AM, et al. After “the China virus” went viral: racially charged coronavirus coverage and trends in bias against Asian Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(6):870-879. doi: 10.1177/1090198120957949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ta Park VM, Dougan MM, Meyer OL, et al. Discrimination experiences during COVID-19 among a national, multi-lingual, community-based sample of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: COMPASS findings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):924. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeung R, Yellow Horse A, Popovic T, Lim R. Stop AAPI Hate National Report. Ethn Stud Rep. 2021;44(2):19-26. doi: 10.1525/esr.2021.44.2.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saw A, Yellow Horse AJ, Jeung R. Stop AAPI Hate mental health report. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Stop-AAPI-Hate-Mental-Health-Report-210527.pdf

- 15.Lurie N, Dubowitz T. Health disparities and access to health. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1118-1121. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Health disparities experienced by black or African Americans--United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(1):1-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cyrus E, Clarke R, Hadley D, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on African American communities in the United States. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):476-483. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abedi V, Olulana O, Avula V, et al. Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):732-742. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galea S, Abdalla SM. COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment, and civil unrest: underlying deep racial and socioeconomic divides. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227-228. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor DB. George Floyd protests: a timeline. New York Times. Published September 7, 2021. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/article/george-floyd-protests-timeline.html

- 21.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335-351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:130-151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou T, Asnaani A, Hofmann SG. Perception of racial discrimination and psychopathology across three U.S. ethnic minority groups. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(1):74-81. doi: 10.1037/a0025432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlisle SK. Perceived discrimination and chronic health in adults from nine ethnic subgroups in the USA. Ethn Health. 2015;20(3):309-326. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.921891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.All of Us Research Hub . Data browser: COVID-19 Participant Experience (COPE). Accessed April 1, 2022. https://databrowser.researchallofus.org/survey/covid-19-participant-experience

- 27.Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, et al. ; All of Us Research Program Investigators . The “All of Us” Research Program. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):668-676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. A diagnostic meta-analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) algorithm scoring method as a screen for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):67-75. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbeke G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. In: Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, eds. Linear Mixed Models in Practice: A SAS-Oriented Approach. Springer New York; 1997:63-153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2294-1_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bates D, Sarkar D, Bates MD, Matrix L. The lme4 package: linear mixed-effects models. R project for statistical computing. 2007;2(1):74.

- 32.Lüdecke D. Ggeffects: tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. J Open Source Softw. 2018;3(26):772-776. doi: 10.21105/joss.00772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delgado-Rodríguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(8):635-641. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.008466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.All of Us Research Program . All of Us Researcher Workbench. National Institute of Health. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://workbench.researchallofus.org/

- 35.Lee S, Waters SF. Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma Health. 2020;6(1):70-78. doi: 10.1037/sah0000275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chae DH, Yip T, Martz CD, et al. Vicarious racism and vigilance during the COVID-19 pandemic: mental health implications among Asian and Black Americans. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(4):508-517. doi: 10.1177/00333549211018675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu C, Qian Y, Wilkes R. Anti-Asian discrimination and the Asian-white mental health gap during COVID-19. Ethn Racial Stud. 2021;44(5):819-835. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1851739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Comparison of sociodemographic characteristics among the COPE respondents (Nrespondent = 62,651), stratified by self-reported race and ethnicity

eTable 2. Distribution of the mean ratings on the Everyday Discrimination Scale by survey timing and self-reported race and ethnicity

eTable 3. Distribution of depressive symptom severity (based on the PHQ-9 score) by survey timing

eTable 4. Variations in the associations of everyday with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by the main reason for discrimination and survey timing

eTable 5. Variations in the associations of everyday discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by the main reason for discrimination and prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis

eFigure 1. Distribution of the mean item score on the Everyday Discrimination Scale among participants who reported everyday discrimination (Nrespondent = 35,844), stratified by survey timing and self-reported race and ethnicity

eFigure 2. Variations in the associations of everyday discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by survey timing, estimated from mixed-effects models

eFigure 3. Variations in the associations of everyday discrimination with moderate to severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by prepandemic mood disorder diagnosis, estimated from mixed effect models

eMethods

eReferences