Abstract

Objective

To describe missed opportunities for vaccination (MOV) among children visiting Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-supported facilities, their related factors, and to identify reasons for non-vaccination.

Design

Cross-sectional surveys conducted between 2011 and 2015.

Setting and participants

Children up to 59 months of age visiting 19 MSF-supported facilities (15 primary healthcare centres and four hospitals) in Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mauritania, Niger, Pakistan and South Sudan. Only children whose caregivers presented their vaccination card were included.

Outcome measures

We describe MOV prevalence and reasons for no vaccination. We also assess the association of MOV with age, type of facility and reason for visit.

Results

Among 5055 children’s caregivers interviewed, 2738 presented a vaccination card of whom 62.8% were eligible for vaccination, and of those, 64.6% had an MOV. Presence of MOV was more likely in children visiting a hospital or a health facility for a reason other than vaccination. MOV occurrence was significantly higher among children aged 12–23 months (84.4%) and 24–59 months (88.3%) compared with children below 12 months (56.2%, p≤0.001). Main reasons reported by caregivers for MOV were lack of vaccines (40.3%), reason unknown (31.2%) and not being informed (17.6%).

Conclusions

Avoiding MOV should remain a priority in low-resource settings, in line with the new ‘Immunization Agenda 2030’. Children beyond their second year of life are particularly vulnerable for MOV. We strongly recommend assessment of eligibility for vaccination as routine healthcare practice regardless of the reason for the visit by screening vaccination card. Strengthening implementation of ‘Second year of life’ visits and catch-up activities are proposed strategies to reduce MOV.

Keywords: Public health, Epidemiology, Organisation of health services, Paediatric infectious disease & immunisation, Community child health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The major strength of the study is that only children with a valid vaccination card were included, so not relying on self-reported data helped to avoid potential recall bias.

Differences by gender on missed opportunities for vaccination were not explored.

Reasons related with missed opportunities for vaccination were limited to those included at the questionnaire and declared by caregivers.

Introduction

Since 1983, the Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) has recommended using every healthcare visit as an opportunity to immunise each eligible child, regardless of the reason for consultation. A missed opportunity for vaccination (MOV) occurs when a child eligible for vaccination (without contraindication) remains unvaccinated or partially vaccinated (not up to date) at the end of the visit, so the consultation does not result in the children receiving all the vaccine doses for which he or she was eligible. Among the causes for undervaccination in low and middle-income countries, 44% are for reasons related to health systems, including MOV and lack of access to healthcare.1 In 1993, the first systematic review including 45 countries found a median MOV prevalence of 67%,2 and despite increases in routine vaccination coverage since then, MOV remains as high as 32% in the last systematic review performed in 2014.3 Since then, the WHO has promoted the use of MOV assessments to measure the performance of health services in vaccination.4 5 In order to improve immunisation coverage, in 2017 WHO recommended a revised methodology to assess MOV, targeting children aged 0–23 months.6 However, data are scarce on MOV prevalence in children above 23 months of age.3 Through its medical humanitarian programmes in low and middle-income countries, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) strengthens routine vaccination services regardless of the age of the child, following WHO recommendations,7 in order to reduce the number of undervaccinated and unvaccinated children. Therefore, we took the opportunity to systematically assess MOV in children up to 5 years of age within MSF programmes.

Our objective was to describe MOV prevalence and its characteristics, and to identify reasons for non-vaccination among children up to 5 years of age visiting MSF-supported health facilities in six different countries.

Methods

Study design and settings

A cross-sectional exit survey of caregivers was performed in 19 health facilities. They included four hospitals and 15 primary healthcare centres (PHCC) between 2011 and 2015 in six countries: Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mauritania, Niger, Pakistan and South Sudan. Countries, health facilities and time of the assessments were chosen on a convenient basis following operational reasons. Facilities included were chosen because MSF was already supporting routine vaccination and where MOV training to local staff was feasible in those health facilities.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Study population and participant selection

The study population consisted of children up to 5 years of age accompanied by a caregiver, visiting an MSF-supported facility. A convenience sample of all caregivers accompanying a child under 5 years of age was approached on the day of the survey at each facility. Caregivers were invited to participate when exiting the facility, regardless of the reason for their visit, and those who provided oral consent were interviewed. If several children were present with one caregiver, all were included. Children whose caregivers could not present a vaccination card were excluded from the analysis.

Data collection

MSF developed a standardised methodology to assess MOV based on the 1988 WHO tool.8 Interviews were conducted in local languages. In preparation for the survey, surveyors locally recruited received 2 days of training focusing on conducting the interview and identifying eligible children for vaccination according to national vaccination schedules, age of the child and minimum interval between doses.

A structured questionnaire was created (online supplemental annex 1) and used in all assessments. Information on type of facility (hospital or PHCC), age of the child, presentation of a vaccination card, reason for visiting the facility and vaccination history was collected, as well as whether there was a contraindication for vaccination. We considered as contraindications fever above 38.5°C and a severe allergic reaction to a previous dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-containing or measles-containing vaccines.

bmjopen-2021-059900supp001.pdf (47.2KB, pdf)

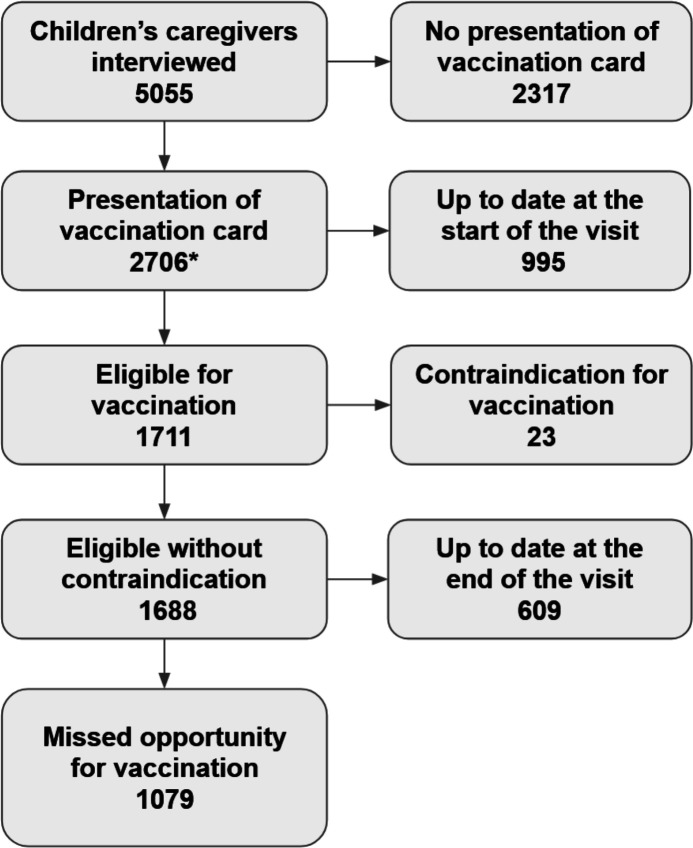

We classified children as having an MOV as per standard WHO’s definition6: an MOV occurs when a child eligible for vaccination (without contraindication) remains unvaccinated or partially vaccinated (not up to date) at the end of any visit to a health facility (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants’ inclusion and for determining missed opportunities for vaccination (MOV), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-supported health facilities, 2011–2015. *Thirty-two children were not included due to data inconsistencies.

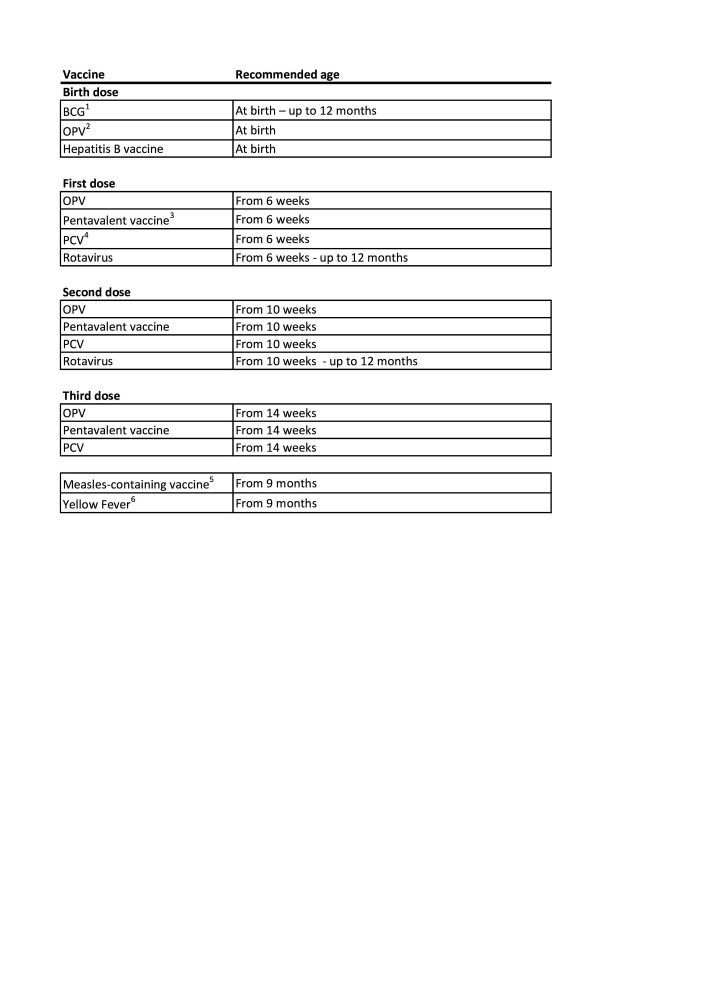

Surveyors determined if the child was eligible that day of the assessment for at least one vaccine dose according to age and national immunisation schedules (figure 2), and whether the child had received all the recommended vaccines during that visit. Most of national immunisation programmes allowed vaccination until 12 months of age by the time of the assessments. Nevertheless, MSF supported vaccination of children up to 5 years of age in each of these facilities. In our study, surveyors considered an MOV if a child did not receive the indicated vaccines even if they were above the recommended age to receive them according to the country policy, to the exception of BCG and rotavirus (figure 2). Only widely introduced vaccines in each country were considered to ascertain MOV. Year of vaccine introduction in each country can be consulted here.9

Figure 2.

Immunisation schedule to ascertain missed opportunity for vaccination (MOV). 1BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine. 2OPV, oral poliovirus vaccine. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine was not considered for MOV. 3Pentavalent vaccine: diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-hepatitis B-Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. 4PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. 5Only one dose of measles containing vaccine was considered for MOV. 6Yellow fever was considered for MOV only in endemic countries. The minimum interval between birth, first, second and third doses was four weeks.

For those having an MOV, surveyors asked for reasons why the child was not vaccinated, whether caregivers would have accepted receiving the missing vaccine doses and about their awareness of the next vaccination appointment.

Data analysis

We calculated the prevalence of MOV among children eligible for a vaccination, excluding those with a reported contraindication. Among children with an MOV we calculated the proportion of caregivers who would have accepted vaccination if it had been proposed on the day of the visit and the proportion of caregivers who knew their date of next vaccination appointment.

Proportions were used to describe the children and to estimate MOV. Significant differences in the distribution were assessed using the Pearson’s two-sided χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. For the bivariate analysis, age was categorised as below and above 12 months of age as this was the main target of the national programme schedules in countries included at the time the survey was performed. Reasons for visit to the facility were grouped into either vaccination or others. We assessed the association of MOV with age, type of facility and reason for visit by calculating ORs. A logistic regression model was adjusted for age (0–11, 12–59 months), type of facility (hospital, PHCC) and reason for visit (vaccination, other reason). The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

In each facility, data entry officers inputted the paper questionnaire data into an Excel database, which was validated by two of the study investigators.10 The analysis was performed using STATA (V.16, College Station, Texas).

Ethics issues

Prior to each evaluation, authorisation from the local health authorities and from the director of each health facility was obtained. Oral consent was received from each caregiver. During the survey, children identified with MOV were sent back to the vaccination unit to receive the missing vaccine(s) if the caregiver agreed and if there was no shortage. All data from the questionnaires were anonymous and entered into a dedicated password-protected electronic database.

Results

From 2011 to 2015, the caregivers of 5055 children were interviewed in 19 facilities (4 hospitals and 15 PHCCs). We report the results for the 2706 (53.5%) children who presented their vaccination card on the day of the survey: 33 from Afghanistan, 79 from Democratic Republic of the Congo, 244 from Mauritania, 1888 from Niger, 15 from Pakistan and 447 from South Sudan. Characteristics of children not presenting vaccination cards can be consulted at online supplemental table 1.

bmjopen-2021-059900supp002.pdf (79.9KB, pdf)

Characteristics of the study population

Among the 2706 children included, 995 (36.7%) were already up to date before the visit, and 1711 (63.2%) were eligible for vaccination. Twenty-three caregivers (1.3%) reported a contraindication (figure 1). Among eligible children, 609 (36.1%) were vaccinated during the visit, whereas 1079 (63.9%) experienced an MOV during their health facility visit.

Children’s baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. Their mean age was 10.1 months (SD=9). The majority (2213, 81.8%) were interviewed at exit of a PHCC. Reasons for visiting the health facility were distributed among curative consultation (31%), followed by unspecified reason (26%), vaccination (16%), nutrition (16%), mother and child health visit (10%) and accompanying an adult (1%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of children who visited MSF-supported health facilities and the presence of missed opportunities for vaccination (MOV), 2011–2015

| Total children n=2706 n (%) |

Eligible for vaccination* n=1688 n (%)† |

MOV | P value | ||

| No n (%)‡ |

Yes n (%)‡ |

||||

| Age groups (months) | |||||

| <12 | 1805 (66.7) | 1203 (66.5) | 540 (44.9) | 663 (55.1) | <0.001§ |

| 12–23 | 597 (22.1) | 314 (52.6) | 49 (15.6) | 265 (84.4) | |

| 24–59 | 304 (11.2) | 171 (56.3) | 20 (11.7) | 151 (88.3) | |

| Facility type | |||||

| Hospital | 493 (18.2) | 336 (68.2) | 67 (19.9) | 269 (80.1) | <0.001§ |

| PHCC | 2213 (81.8) | 1352 (61.1) | 542 (40.1) | 810 (59.9) | |

| Reason of the visit | |||||

| Curative | 831 (30.7) | 513 (61.7) | 40 (7.8) | 473 (92.2) | <0.001¶ |

| Other | 706 (26.1) | 311 (44.1) | 281 (90.3) | 30 (9.7) | |

| Vaccination | 436 (16.1) | 353 (81.0) | 234 (64.3) | 119 (33.7) | |

| Nutrition | 430 (15.9) | 275 (64.0) | 23 (8.4) | 252 (91.6) | |

| Mother–child health visit | 265 (9.8) | 214 (80.8) | 29 (13.5) | 185 (86.5) | |

| Accompanying | 38 (1.4) | 22 (57.9) | 2 (9.1) | 20 (90.9) | |

*Without contraindication for vaccination.

†Row percentage over the total children.

‡Row percentage over the eligible children without contraindication for vaccination.

§Χ2 test.

¶Fisher’s exact test.

MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; PHCC, primary healthcare centre.

Characteristics of children with MOV

Most children who were eligible for vaccination and consulting for a reason other than vaccination had an MOV (n=960, 71.9%), while a third of the children coming to the facility for vaccination also had an MOV (n=119, 33.7%). More than 80% of children aged 12–23 months (265/314) and almost 90% of children aged 23–59 (151/171) had an MOV, compared with 55% of children below 12 months (663/1203). MOV occurrence was significantly more likely among older children than younger ones (table 1). Differences in MOV by country can be consulted at online supplemental table 2.

Only four caregivers of children with MOV would have refused vaccination if it had been proposed during the visit. About one-fifth (21%) of caregivers of children with MOV were aware of the date of the next vaccination appointment.

The most common reason declared for having an MOV was lack of vaccines (40.1%), followed by reason unknown (32%), not being informed (17.3%), lack of staff (3.3%), waiting time too long (1.7%) and other unclassified reasons (5.6%).

Factors related with presence of MOV

Children above 12 months of age and those accessing the health facility for a reason other than vaccination had an almost five times higher risk of having an MOV (table 2), compared with children below 12 months of age and those visiting for vaccination. Children visiting a hospital had a 2.7 times higher risk of having an MOV compared with children visiting a PHCC. After adjusting by type of facility and reason for visit, children above 12 months still had a significantly higher risk of having an MOV (adjusted OR: 1.7, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.5).

Table 2.

Factors related to missed opportunities for vaccination (MOV) in eligible children who visited MSF-supported health facilities, 2011–2015

| MOV children n=1079 n (%) |

OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (months) | |||

| 0–11 | 663 (55.1) | ||

| 12–59 | 416 (85.8) | 4.91 (3.67 to 6.57) | 3.79 (2.84 to 5.07) |

| Reason for visiting | |||

| Vaccination | 119 (33.7) | ||

| Other | 960 (89.0) | 5.03 (3.86 to 6.56) | 3.52 (2.70 to 4.58) |

| Facility type | |||

| PHCC | 810 (59.9) | ||

| Hospital | 269 (80.1) | 2.69 (2.00 to 3.60) | 2.75 (2.02 to 3.73) |

OR adjusted for age, reason for visiting and facility type (two categories each).

MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; PHCC, primary healthcare centre.

Discussion

This study summarises the MSF experience and lessons learnt assessing MOV from 2011 to 2015 in six low-income countries. To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies that assessed MOV in children beyond 23 months of age. Our results highlight that, despite MSF’s efforts, most children had an MOV after visiting one of the facilities. Even among those children who specifically visited for vaccination, one-third still missed at least one dose of a vaccine for which they were eligible during the visit. The proportion of children with MOV increased with age, with children above 1 year of age being at higher risk.

MOV prevalence in our study (64%) was higher than the last systematic review conducted in low-income countries in 2014, which found a prevalence of 32% (26.8–37.7).3 An explanation could be that the majority of studies in this meta-analysis only included children below 2 years of age resulting in a lower estimation of MOV. As our data show, MOV was nearly 90% in children above 23 months of age. One of the few studies that include older children also reported that MOV prevalence was higher in children aged 1–5 years (56.6%), compared with those below 1 year (31.4%).11 Thus, we believe that overall MOV prevalence is being seriously underestimated, as assessments do not include children beyond the EPI age target for most vaccines, that is, above 23 months of age.

Consistent with recent studies in low-income countries,12 we found a higher MOV prevalence in children above 12 months. In a recent study that assessed MOV with WHO methodology in Chad and Malawi, Ogbuanu et al13 found an MOV prevalence of 86% in Chad and 94% in Malawi among children above 1 year of age, compared with 49% and 61% below 1 year, respectively.

Age as a risk for having MOV may be explained by older children having been perceived as ‘too old’ to be eligible,14 as many national immunisation programmes only target children below 1 year of age. Age as a false contraindication was found to be one of the main reasons for having an MOV in a WHO review about factors related with undervaccination.15 For example, in 2013 WHO removed age restriction for rotavirus vaccine in the WHO African region, nevertheless it is not implemented in many countries.16 17 But efforts are being made to ‘Leave No One Behind’18: the latest WHO update of recommendations for routine immunisation19 emphasises that measles vaccine should not be limited to children up to 12 months of age. In line with that, a ‘second year of life healthy child visit’ is already recommended by WHO7 20 increasing the opportunity to vaccinate children, especially in those who might have missed vaccination in their first year of life. This strategy, together with complementary catch-up activities to continue screening children at any contact with health services, should be strengthened in low-resource settings.7 21–23 We believe this ‘never too old’ policy should be adopted by all national immunisation programmes in order to ensure children do not miss the opportunity to be fully vaccinated at any age.

Our data draw attention to the high proportion of children missing an opportunity to get vaccinated at hospital level. A similar proportion has been found in a recent study performed in northern Indian hospitals.24 This could be explained by vaccine shortage at hospital level but also by the belief in the false contraindication for vaccination in a sick child among caregivers and healthcare workers. For example, a study in Haiti reported that up to 13% of reasons for undervaccination were child illness, despite the fact that mild infections should not prevent vaccination.25 A similar finding is highlighted in an MOV assessment in Timor-Leste, where Li et al14 found that only 24% of healthcare workers were able to identify true contraindications, and Kaboré et al12 reported that 83% of health workers failed to correctly identify valid contraindications for vaccination. This could be avoided through the proper adherence to the Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illnesses guidelines,22 already in place in these countries.26

We identified that one-third of children actually visiting for vaccination were still not up to date at the end of the visit despite being vaccinated with one or more doses. Similar estimates were found in four recent MOV assessments in Timor-Leste, Chad, Malawi and Burkina Faso.12–14 This could be explained by supply shortages of specific vaccines, but also by health workers potentially failing to identify eligibility for certain vaccines. Failure to administer simultaneous vaccines due to fear of wasting doses from multivial vaccines has also been suggested as an explanation for remaining MOV after vaccination visits.27 28 Among reasons for MOV in our study, almost 20% reported not being informed by healthcare workers about the eligibility of the child for vaccination. This lack of information on vaccine eligibility has also been reported elsewhere.29 Therefore, promoting training on eligibility assessment and true contraindications for vaccination among healthcare workers could be an effective strategy to reduce MOV.30

Over three-quarters of eligible children consulting for reasons other than vaccination (mother and child health visits, nutrition, curative) had an MOV. This highlights the need of strengthening routine screening of vaccination status that must be done irrespective of reason visit. Caregivers should be encouraged to bring the vaccination card to every contact with health services, to facilitate and ensure that the child can be properly screened for vaccination eligibility. So, integrating vaccination into other preventive or curative services at hospital and at primary healthcare level could facilitate a significant reduction on MOV.31 32

In our study, caregivers reported lack of vaccines as the main reason for MOV. This is consistent with recent MOV assessments,13 where approximately 30% of healthcare workers reported insufficient vaccine supply or logistics issues. Inadequate vaccine supply has already been pointed out as one of the main reasons for undervaccination in low-income countries.1 Ministries of Health and their partners must work to ensure adequate vaccine supply at facility level in order to be able to vaccinate any children who have accessed healthcare services.33

This study is not from a representative sample, and very few children were eligible in two of the six countries included (online supplemental table 2). It has three main limitations. First, gender was not collected, losing the opportunity to uncover gender differences. Nevertheless, no gender differences in the distribution of MOV have been reported in the latest studies.3 13 Second, our survey didn’t allow us to explore healthcare providers’ practices and perceptions, identified as one of the main reasons related to MOV in the last systematic review.3 In 2015, WHO launched a revised MOV strategy, which included Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices questionnaires, to better guide the implementation of interventions to reduce MOV13 which is generating new evidence.34 Also, we could not explore other factors that have been previously related to MOV such as maternal education, living in rural areas, number of children and other economic inequalities, as information on contacted caregivers was not kept35 and, unfortunately, we do not have information to estimate the participation rate.

Third, we excluded from the analysis almost half of the children whose caregivers could not present a vaccination card. This may mean that we underestimated MOV prevalence in our target population, since not presenting a vaccination card has shown to be associated with MOV.1 3 36 On the one hand, not relying on self-reported data helped avoid potential recall bias, which is a limitation in vaccine coverage studies in low-resource settings.37 On the other hand, possession of vaccination card declines with age11 (a relation also observed in our study, online supplemental table 1); what could result in an overestimated prevalence of MOV in older children. Nevertheless, when assessing the relation between MOV and age including those with and without vaccination card, we obtain similar results (online supplemental table 3).

Finally, as children with identified MOV were sent back for vaccination when possible, it could have introduced a bias in MOV prevalence if these children were inadvertently interviewed again. Also, MOV prevalence estimates may have improved over the last 10 years, as WHO has lately reinforced EPI vaccination during the second year of life.

Conclusions

Despite progress in vaccine coverage, MOV remains an important problem in low-resource settings. Avoiding MOV should remain a priority where access to healthcare is limited, in line with the new ‘Immunization Agenda 2030’.18 This is particularly important considering the negative impact COVID-19 pandemic is having on routine immunisation programmes in low and middle-income countries.38 39

We recommend integrating systematic vaccination screening into routine healthcare services, regardless of the reason for the visit, the type of facility and the age of the child. To promote maintaining and providing vaccination cards at every healthcare visit will help reinforce vaccination screening and better identification of eligible children.

We identified that children above 23 months of age are particularly vulnerable for MOV. Thus, we would recommend including children beyond 23 months of age in the current WHO methodology for MOV assessments in order to avoid underestimation of MOV. National immunisation programmes should allow administration of missing doses, regardless of the age of the child, as the EPI has expanded its vaccination recommendations during the second year of life and beyond.

Strengthening the implementation of second year of life visits, as recommended by WHO, with catch-up vaccination strategies7 would provide additional opportunities to receive missed vaccine doses and leave no one behind.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the caregivers for sharing their invaluable time and all the healthcare workers who performed the assessments. Special thanks to Ibrahim Barrie and Marie-Eve Burny for implementation of MOV studies in the field. Thanks to Tony Reid for language review and to JA Rodrigo for his valuable input.

Footnotes

IP and CB contributed equally.

Contributors: CB and IP designed the study and contributed to the conduct of the study in six countries. CB, IP, JG-C and BB-B carried out the data analysis. BB-B drafted the manuscript that was critically reviewed and approved by all the authors. BB-B acts as guarantor for the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was carried out by the MSF staff as part of their routine activities.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Questionnaire data set is available in a public, open access repository. [data set] BB-B. Data from: Missed Opportunities for Vaccination in MSF-Supported Health Facilities. Open Science Framework. 6 December 2021. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SFXDK.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This research fulfilled the exemption criteria by Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Review Board (MSF ERB) for a posteriori analysis of routinely collected clinical data and thus did not require MSF ERB review. It was conducted with permission from the Medical Director, Operational Centre Brussels, Médecins Sans Frontières.

References

- 1.Rainey JJ, Watkins M, Ryman TK, et al. Reasons related to non-vaccination and under-vaccination of children in low and middle income countries: findings from a systematic review of the published literature, 1999-2009. Vaccine 2011;29:8215–21. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchins SS, Jansen HA, Robertson SE, et al. Studies of missed opportunities for immunization in developing and industrialized countries. Bull World Health Organ 1993;71:549–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sridhar S, Maleq N, Guillermet E, et al. A systematic literature review of missed opportunities for immunization in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 2014;32:6870–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.10.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Methodology for the Evaluation of Missed Opportunities for Vaccination [Internet]. Pan American Health Organization, 2014. Available: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2015/MissedOpportunity-Vaccination-Protocol-2014.pdf

- 5.Velandia-González M, Trumbo SP, Díaz-Ortega JL. Lessons learned from the development of a new methodology to assess missed opportunities for vaccination in Latin America and the Caribbean 2011;15:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Methodology for the Assessment of Missed Opportunities for Vaccination [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259201 [Accessed 22 Feb 2021].

- 7.Leave no one behind: guidance for planning and implementing catch-up vaccination [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/leave-no-one-behind-guidance-for-planning-and-implementing-catch-up-vaccination [Accessed 27 Feb 2022].

- 8.Sato PA, WEP on I. Protocole pour l’ évaluation des occasions manquées de vaccination / Paul Sato, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Immunization Data portal [Internet]. Available: https://immunizationdata.who.int/listing.html?topic=&location= [Accessed 19 Mar 2022].

- 10.Borras-Bermejo B. Data from: missed opportunities for vaccination in MSF-Supported health facilities. Open Science Framework 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garib Z, Vargas AL, Trumbo SP, et al. Missed opportunities for vaccination in the Dominican Republic: results of an operational investigation. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:1–9. 10.1155/2016/4721836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaboré L, Meda B, Médah I, et al. Assessment of missed opportunities for vaccination (Mov) in Burkina Faso using the world Health organization's revised Mov strategy: findings and strategic considerations to improve routine childhood immunization coverage. Vaccine 2020;38:7603–11. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogbuanu IU, Li AJ, Anya B-PM, et al. Can vaccination coverage be improved by reducing missed opportunities for vaccination? findings from assessments in Chad and Malawi using the new who methodology. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210648. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li AJ, Peiris TSR, Sanderson C, et al. Opportunities to improve vaccination coverage in a country with a fledgling health system: findings from an assessment of missed opportunities for vaccination among health center attendees-Timor Leste, 2016. Vaccine 2019;37:4281–90. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epidemiology of the Unimmunized Child . Findings from the grey literature. prepared for the world Health organization. October 2009. immunization basics project. Geneva World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Organization WH. Rotavirus vaccines: WHO position paper - July 2021. Wkly Epidemiol Rec;96:301–219. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandomando I, Mumba M, Nsiari-Muzeyi Biey J, et al. Implementation of the world Health organization recommendation on the use of rotavirus vaccine without age restriction by African countries. Vaccine 2021;39:3111–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind [Internet], 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/strategies/ia2030 [Accessed cited 2021 Feb 22].

- 19.World Health Organization . Table 2 : Summary of WHO Position Papers - Recommended Routine Immunizations for Children [Internet], 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/immunization/immunization_schedules/immunization-routine-table2

- 20.Establishing and strengthening immunization in the second year of life : Practices for vaccination beyond infancy [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260556/9789241513678-eng.pdf [Accessed cited 2021 Oct 28].

- 21.Standards for improving the quality of care for children and young adolescents in health facilities [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565554 [Accessed 28 Oct 2021].

- 22.Integrated management of childhood illness: caring for newborns and children in the community. [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44398 [Accessed 18 Sep 2021].

- 23.Hanson CM, Mirza I, Kumapley R, et al. Enhancing immunization during second year of life by reducing missed opportunities for vaccinations in 46 countries. Vaccine 2018;36:3260–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albaugh N, Mathew J, Choudhary R, et al. Determining the burden of missed opportunities for vaccination among children admitted in healthcare facilities in India: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046464. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rainey JJ, Lacapère F, Danovaro-Holliday MC, et al. Vaccination coverage in Haiti: results from the 2009 national survey. Vaccine 2012;30:1746–51. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boschi-Pinto C, Labadie G, Dilip TR, et al. Global implementation survey of integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI): 20 years on. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019079. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallace AS, Willis F, Nwaze E, et al. Vaccine wastage in Nigeria: an assessment of wastage rates and related vaccinator knowledge, attitudes and practices. Vaccine 2017;35:6751–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace AS, Krey K, Hustedt J, et al. Assessment of vaccine wastage rates, missed opportunities, and related knowledge, attitudes and practices during introduction of a second dose of measles-containing vaccine into Cambodia's national immunization program. Vaccine 2018;36:4517–24. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gil Cuesta J, Whitehouse K, Kaba S. ‘When you welcome well, you vaccinate well’: a qualitative study on improving vaccination coverage in urban settings in Conakry, Republic of Guinea. Int Health 2020;00:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaca A, Mathebula L, Iweze A, et al. A systematic review of strategies for reducing missed opportunities for vaccination. Vaccine 2018;36:2921–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Restrepo-Méndez MC, Barros AJD, Wong KLM, et al. Missed opportunities in full immunization coverage: findings from low- and lower-middle-income countries. Glob Health Action 2016;9:30963. 10.3402/gha.v9.30963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Practical guide for the design, use and promotion of home-based records in immunization programmes [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/175905/WHO_IVB_15.05_eng.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y [Accessed 28 Oct 2021].

- 33.2017 Assessment Report of the Global Vaccine Action Plan. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/immunization/web_2017_sage_gvap_assessment_report_en.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed cited 2021 Oct 28].

- 34.Fatiregun AA, Lochlainn LN, Kaboré L, et al. Missed opportunities for vaccination among children aged 0-23 months visiting health facilities in a southwest state of Nigeria, December 2019. PLoS One 2021;16:e0252798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ndwandwe D, Uthman OA, Adamu AA, et al. Decomposing the gap in missed opportunities for vaccination between poor and non-poor in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry analyses. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018;14:2358–64. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1467685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olorunsaiye CZ, Langhamer MS, Wallace AS, et al. Missed opportunities and barriers for vaccination: a descriptive analysis of private and public health facilities in four African countries. Pan Afr Med J 2017;27:6. 10.11604/pamj.supp.2017.27.3.12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil Cuesta J, Mukembe N, Valentiner-Branth P, et al. Measles vaccination coverage survey in MobA, katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2013: need to adapt routine and mass vaccination campaigns to reach the unreached. PLoS Curr 2015;7. 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.8a1b00760dfd81481eb42234bd18ced3. [Epub ahead of print: 02 Feb 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Second round of the national pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: January-March 2021: interim report, 22 April 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340937 [Accessed 28 Oct 2021].

- 39.COVID-19 pandemic leads to major backsliding on childhood vaccinations, new WHO, UNICEF data shows [Internet]. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-07-2021-covid-19-pandemic-leads-to-major-backsliding-on-childhood-vaccinations-new-who-unicef-data-shows [Accessed 19 Mar 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-059900supp001.pdf (47.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059900supp002.pdf (79.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Questionnaire data set is available in a public, open access repository. [data set] BB-B. Data from: Missed Opportunities for Vaccination in MSF-Supported Health Facilities. Open Science Framework. 6 December 2021. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SFXDK.