Abstract

A novel secondary intracellular symbiotic bacterium from aphids of the genus Yamatocallis (subfamily Drepanosiphinae) was characterized by using molecular phylogenetic analysis, in situ hybridization, and diagnostic PCR detection. In the aphid tissues, this bacterium (tentatively designated YSMS [Yamatocallis secondary mycetocyte symbiont]) was found specifically in large cells surrounded by primary mycetocytes harboring Buchnera cells. Of nine drepanosiphine aphids examined, YSMS was detected in only two species of the same genus, Yamatocallis tokyoensis and Yamatocallis hirayamae. In natural populations of these aphids, YSMS was present in 100% of the individuals. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences demonstrated that YSMS of Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae constitute a distinct and isolated clade in the γ subdivision of the class Proteobacteria. No 16S rDNA sequences of secondary endosymbionts characterized so far from other aphids showed phylogenetic affinity to YSMS. Based on these results, I suggest that YSMS was acquired by an ancestor of the genus Yamatocallis and has been conserved throughout the evolution of the lineage. By using the nucleotide substitution rate for 16S rDNA of Buchnera spp., the time of acquisition of YSMS was estimated to be about 13 to 26 million years ago, in the Miocene epoch of the Tertiary period.

To date, about 4,400 species of aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) have been described in 11 subfamilies (2). Almost all of these species have an intracellular symbiotic bacterium, Buchnera sp., in the cytoplasm of mycetocytes (or bacteriocytes), which are hypertrophied cells in the abdomen specialized for endosymbiosis (1, 3). The aphids and their Buchnera symbionts are intimately mutualistic; the symbionts cannot survive when they are removed from the host cells, and the aphids are sterile or die when they are deprived of their symbionts (17, 18, 21). It is thought that the aphids provide their Buchnera symbionts with a stable niche and nutrients, while the Buchnera symbionts synthesize essential amino acids and other nutrients for their hosts (1, 8, 9). The evolutionary origin of the endosymbiotic association is believed to be quite ancient. Buchnera symbionts of various distantly related aphid species are descended from a bacterium that was acquired by the common ancestor of extant aphids and have speciated with their hosts (19). Phylogenetically, the Buchnera symbionts belong to the γ subdivision of the class Proteobacteria (γ-Proteobacteria) (23). Because of their prevalence and importance in aphids, Buchnera spp. and the mycetocytes harboring them are often referred to as primary symbionts (P-symbionts) and primary mycetocytes (P-mycetocytes), respectively.

In addition to the Buchnera P-symbionts, a number of aphids contain additional types of vertically transmitted endosymbiotic bacteria, which have been collectively referred to as secondary symbionts (S-symbionts) or accessory symbionts (3–7, 11, 12, 14–16, 22). Some of the S-symbionts, such as Rickettsia and Spiroplasma spp., do not exhibit remarkable cellular localization but populate various tissues and cells rather nonspecifically (3, 5, 13, 16). On the other hand, in many aphids the S-symbionts are harbored in specialized cells, such as secondary mycetocytes (S-mycetocytes) and sheath cells, which constitute a mycetome (or bacteriome) with the P-mycetocytes in the abdomens of the insects (3, 11, 12, 14, 15, 22). These additional symbionts that populate specific S-mycetocytes, which I refer to as secondary mycetocyte symbionts (SM-symbionts) below, are found in many, but not all, lineages of aphids, exhibit remarkable differences in morphology, localization, and quantity in different lineages, and are thought to have polyphyletic evolutionary origins (3, 11, 12, 14–16, 22).

Although classical microscopic and recent histochemical studies have documented a wide variety of morphotypes of SM-symbionts in many lineages of aphids (3, 11, 12, 14), the microbial nature of the SM-symbionts has been phylogenetically characterized in only a limited number of aphids, including Acyrthosiphon pisum (4, 22, 23) and the Uroleucon species complex (22). These aphids belong to the same aphid group, the tribe Macrosiphini in the subfamily Aphidinae. Therefore, in order to understand the origin and evolution of intracellular symbiosis in aphids, it is necessary to characterize SM-symbionts found in different aphid groups.

In this paper, I describe the first characterization of the SM-symbionts found in aphids of the genus Yamatocallis in the subfamily Drepanosiphinae.

Yamatocallis tokyoensis and Yamatocallis hirayamae were collected from Acer spp. in Japan (Table 1). The samples that were collected were preserved in acetone until molecular and histological analyses were performed (10). DNA extraction, PCR, cloning, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) typing, DNA sequencing, molecular phylogenetic analysis, and in situ hybridization were conducted essentially as previously described (13, 15, 16).

TABLE 1.

Aphid samples examined in this study

| Species | Sample no.a | Original locality | Collection date | Host plant | Accession no. of 16S rDNA sequence

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchnera sp. | YSMS | |||||

| Yamatocallis tokyoensis | 207 | Izumi, Suginami-ku, Tokyo, Japan | 11 May 1997 | Acer palmatum | AB064507 | AB064513 |

| 317 | Higashi, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan | 28 April 1998 | Acer palmatum | AB064508 | AB064514 | |

| 525 | Sekimoto, Kita-Ibaraki, Ibaraki, Japan | 20 May 2000 | Acer palmatum | AB064509 | AB064515 | |

| 526 | Yunotake, Iwaki, Fukushima, Japan | 20 May 2000 | Acer palmatum | AB064510 | AB064516 | |

| 566 | Mt. Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan | 31 May 2000 | Acer palmatum | AB064511 | AB064517 | |

| Yamatocallis hirayamae | 567 | Mt. Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan | 31 May 2000 | Acer mono | AB064512 | AB064518 |

| Diphyllaphis konarae | 533 | Yunotake, Iwaki, Fukushima, Japan | 20 May 2000 | Quercus serrata | ||

| Myzocallis kuricola | 58 | Fujimoto, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan | 16 June 1996 | Castanea crenata | ||

| Neocalaphis magnolicolens | 51 | Ninomiya, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan | 15 June 1996 | Magnolia obovata | ||

| Shivaphis celtis | 244 | Amanohashidate, Miyazu, Kyoto, Japan | 20 July 1997 | Zelkova serrata | ||

| Symydobius kabae | 483 | Jozan-kei, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan | 17 June 1999 | Betula ermanii | ||

| Tinocallis kahawaluokalani | 25 | Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku, Tokyo, Japan | 8 June 1996 | Lagerstroemia indica | ||

| Tuberculatus fulviabdominalis | 12 | Izumi, Suginami-ku, Tokyo, Japan | 8 June 1996 | Quercus serrata | ||

Sample number in my acetone-preserved insect sample collection.

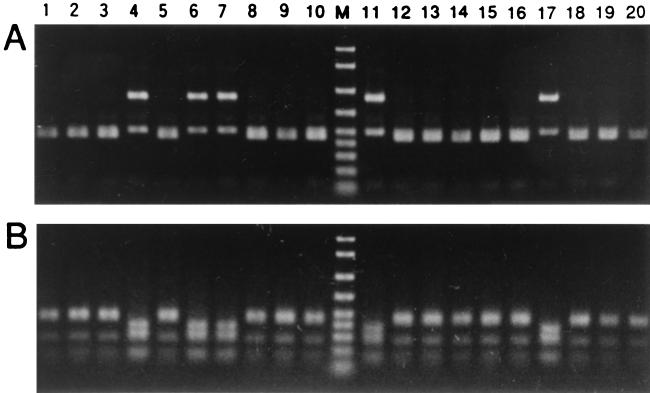

Almost the entire length of the eubacterial 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) was amplified by PCR from sample 207 from Suginami-ku, Tokyo, Japan, and sample 317 from Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan, and the products were cloned. RFLP analysis of the clones revealed the presence of two sequence types, the predominant type A and the relatively minor type B (Fig. 1). Three clones of each type from each sample were sequenced. The type A sequences were 1,486 bp long, while the type B sequences were 1,473 bp long. The type A and B sequences from sample 207 were identical to the type A and B sequences from sample 317, respectively. The type A sequence showed high sequence similarity to 16S rDNA sequences of Buchnera spp. from various aphids. On the other hand, the type B sequence was not as similar to Buchnera sequences as the type A sequence was, although all of the sequences were from members of the same bacterial group, the γ-Proteobacteria.

FIG. 1.

RFLP analysis of bacterial 16S rDNA amplified and cloned from the total DNA of Y. tokyoensis. Lanes 1 through 10 contained 16S rDNA cloned from sample 207, whereas lanes 11 through 20 contained 16S rDNA from sample 317. (A) Rsal digestion. (B) HaeIII digestion. Lanes 1 to 3, 5, 8 to 10, 12 to 16, and 18 to 20, clones containing the type A (Buchnera) sequence; lanes 4, 6, 7, 11, and 17, clones containing the type B (YSMS) sequence. Lane M contained DNA size markers (2,000, 1,500, 1,000, 700, 500, 400, 300, 200, and 100 bp from top to bottom).

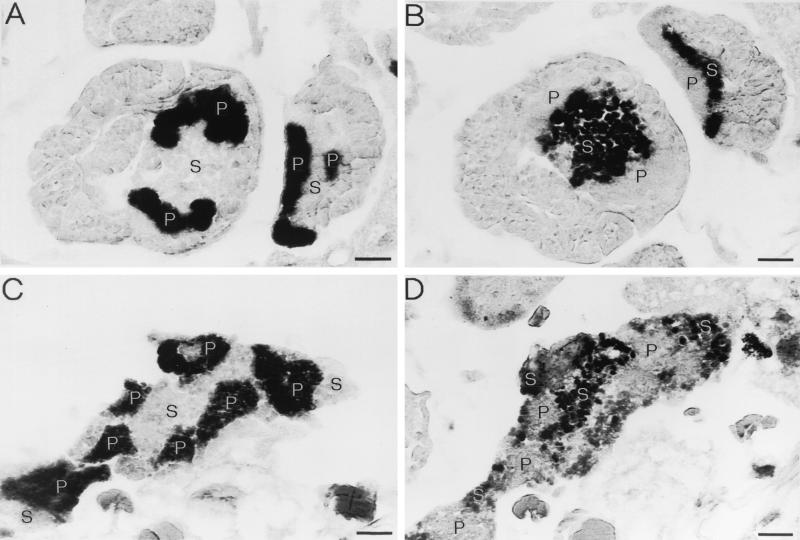

I designed two oligonucleotide probes, DIG-KMGTP (5′- digoxigenin-TCCCCTACTTTGGTTTCTC-3′) and DIG- KMGTS (5′-digoxigenin-TCCCCCACTTTGGTCTTTT-3′), which specifically recognize the type A and B sequences, respectively. Using these probes, I performed 16S rRNA-targeted in situ hybridization with Y. tokyoensis tissue sections (Fig. 2). When probe DIG-KMGTP was used, mycetocytes filled with round bacterial particles were specifically stained in embryonic and maternal mycetomes (Fig. 2A and C). These histological traits, together with the 16S rDNA sequence similarity, indicated that the type A sequence was derived from the P-symbiont, Buchnera sp. When probe DIG-KMGTS was used, round bacterial particles which were larger than Buchnera cells were visualized in large cells surrounded by P-mycetocytes (Fig. 2B and D). Therefore, I demonstrated that the type B sequence was derived from an intracellular symbiotic bacterium harbored in a different type of mycetocyte that constituted a huge mycetome in the abdomen of the host together with the P-mycetocytes. In this paper, I tentatively designate this bacterium YSMS (Yamatocallis secondary mycetocyte symbiont).

FIG. 2.

In situ hybridization of the endosymbiotic bacteria in Y. tokyoensis sample 317. (A) Embryos probed with DIG-KMGTP, which specifically targets the type A sequence. Aggregates of P-mycetocytes filled with Buchnera sp. are deeply stained. (B) Embryos probed with DIG-KMGTS, which specifically targets the type B sequence. A large cytoplasm surrounded by P-mycetocytes harbors a number of round YSMS cells. (C) Maternal mycetome probed with DIG-KMGTP, which specifically targets the type A sequence. Buchnera cells in P-mycetocytes are specifically stained. (D) Maternal mycetome probed with DIG-KMGTS, which specifically targets the type B sequence. YSMS cells in the cytoplasm between P-mycetocytes are visualized. The sections shown in panels A and B were adjacent tissue sections, as were the sections shown in panels C and D. Bars = 20 μm. Abbreviations: P, Buchnera; S, YSMS.

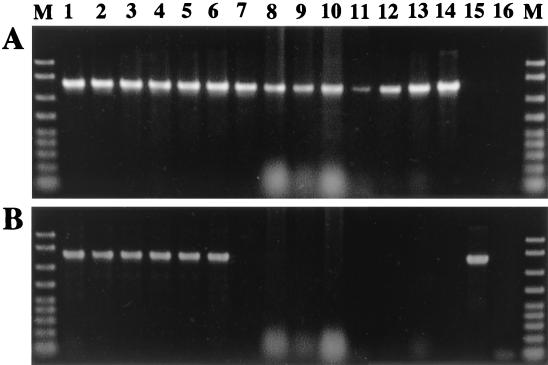

How prevalent is YSMS in aphids? The presence of YSMS in aphids belonging to subfamily Drepanosiphinae was investigated because Y. tokyoensis is a member of the Drepanosiphinae. In addition to Y. tokyoensis samples from five localities, Y. hirayamae and other drepanosiphine aphids (Table 1) were analyzed. The specific reverse primers KMGTPsp (5′-GAACTTTATGAGGTTGGCTTGTC-3′) for Buchnera spp. and KMGTSsp (5′-CTAACTTTAGGTGATCTGCTTACT-3′) for YSMS were used in combination with universal forward primer 16SA1 (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) for diagnostic PCR detection of 16S rDNA of the endosymbionts. Among the aphids examined, YSMS was detected only in Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae (Fig. 3), suggesting the possibility that YSMS was acquired by the common ancestor of the genus Yamatocallis. In situ hybridization experiments confirmed that Y. hirayamae possessed an endosymbiotic system quite similar to that of Y. tokyoensis (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Specific PCR detection of YSMS in aphids of the subfamily Drepanosiphinae. (A) Specific detection of Buchnera spp. with primers 16SA1 and KMGTPsp. (B) specific detection of YSMS with primers 16SA1 and KMGTSsp. Lane 1, Y. tokyoensis sample 207; lane 2, Y. tokyoensis sample 452; lane 3, Y. tokyoensis sample 525; lane 4, Y. tokyoensis sample 526; lane 5, Y. tokyoensis sample 566; lane 6, Y. hirayamae; lane 7, Tinocallis kahawaluokalani; lane 8, Tuberculatus fulviabdominalis; lane 9, Myzocallis kuricola; lane 10, Neocalaphis magnolicolens; lane 11, Diphyllaphis konarae; lane 12, Symydobius kabae; lane 13, Shivaphis celtis; lane 14, plasmid containing 16S rDNA of Buchnera sp. from Y. tokyoensis; lane 15, plasmid containing 16S rDNA of YSMS from Y. tokyoensis; lane 16, no-template control; lane M, DNA size markers (2,000, 1,500, 1,000, 700, 500, 400, 300, 200, and 100 bp from top to bottom). Each sample contained whole DNA from 10 insects.

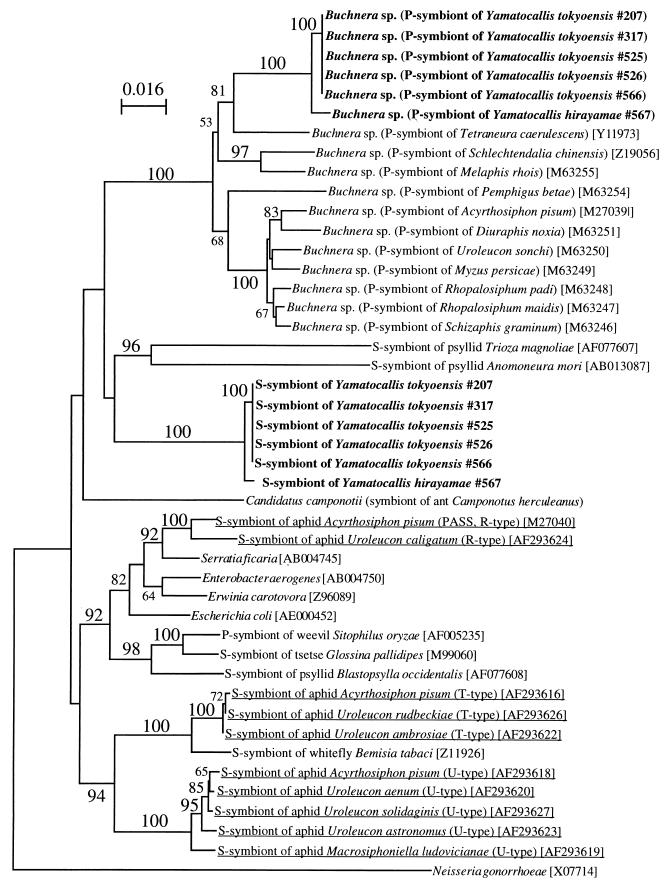

The phylogenetic placement of the endosymbiotic bacteria from Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae was analyzed based on the 16S rDNA sequences (Fig. 4). As expected, the type A sequences were placed in the clade containing Buchnera spp. in the γ-Proteobacteria. On the other hand, the type B sequences had no close relatives but constituted a distinct and isolated lineage in the γ-Proteobacteria. None of the 16S rDNA sequences of S-symbionts from other aphids, such as A. pisum and Uroleucon spp. (Fig. 4), showed phylogenetic affinity to the type B sequence. The 16S rDNA sequence of Buchnera sp. from Y. tokyoensis exhibited 1.03% sequence divergence (13 of 1,260 bases) from the 16S rDNA sequence of Buchnera sp. from Y. hirayamae. On the other hand, the 16S rDNA sequences of YSMS exhibited a slightly lower level of sequence divergence, 0.72% (9 of 1,252 bases), when the sequences from Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae were compared. It should be noted, however, that the nucleotide substitution rate of 16S rDNA in the Buchnera lineage is about 1.5- to 2-fold greater than the corresponding rate estimated for free-living bacteria (20). Therefore, provided that the 16S rDNA of YSMS has a standard substitution rate, the difference in 16S rDNA sequence divergence values, about 1.43-fold (1.03/0.72), indicates that the level of genetic divergence between Y. tokyoensis YSMS and Y. hirayamae YSMS was substantially similar to that of Buchnera spp.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic placement in the γ-Proteobacteria of Buchnera spp. and YSMS from Japanese populations of Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae based on 16S rDNA sequences. A total of 1,140 unambiguously aligned nucleotide sites were subjected to analysis. A neighbor-joining phylogeny is shown, and maximum-parsimony analysis gave essentially the same results. The bootstrap values obtained with 1,000 resamplings are shown at the nodes, although values of less than 50% are not shown. The numbers in brackets are accession numbers. The sequences of S-symbionts from other aphids are underlined.

Finally, in order to examine the infection rate of YSMS in natural populations of Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae, I used diagnostic PCR to detect Buchnera spp. and YSMS (Table 2). In all of the populations, the levels of infection with both Buchnera spp. and YSMS were 100%.

TABLE 2.

Diagnostic PCR detection of Buchnera sp. and YSMS in Japanese populations of Yamatocallis spp.

| Sample

|

% of individuals containing:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Sample no. | Buchnera sp. | YSMS |

| Y. tokyoensis | 207 | 100 (20/20)a | 100 (20/20) |

| 317 | 100 (50/50) | 100 (50/50) | |

| 525 | 100 (20/20) | 100 (20/20) | |

| 526 | 100 (20/20) | 100 (20/20) | |

| 566 | 100 (20/20) | 100 (20/20) | |

| Y. hirayamae | 567 | 100 (12/12) | 100 (12/12) |

The values in parentheses are number of positive individuals/total number of individuals examined.

In previous studies of A. pisum and allied aphids, it has consistently been demonstrated that the S-symbionts are facultative companions for the hosts. The S-symbionts partially infected the populations studied (4, 6, 15, 16, 22). In several cases, it was shown that the S-symbionts had negative effects on the fitness of the host insects (4, 6, 16). It was reported that S-symbionts with little genetic divergence were sporadically detected in different aphid species (4), suggesting that the organisms are sometimes horizontally transmitted between host insects, although the mechanism is not known.

In the present study, in contrast to the S-symbionts of A. pisum, YSMS of Yamatocallis spp. infected all individuals in natural populations, accounted for a substantial fraction of the endosymbiotic biomass, and was specifically detected in aphids in this genus. These results strongly suggest that YSMS was acquired by an ancestor of the genus Yamatocallis and has been conserved throughout the evolution of the lineage. Although the biological function of YSMS is not known, it is plausible that in addition to the essential roles of Buchnera spp. in survival and reproduction of their hosts, YSMS may play supplementary but important roles.

When was YSMS acquired by the ancestral Yamatocallis species? In the Buchnera lineage, 16S rDNA was estimated to evolve at a rate of 0.01 to 0.02 substitution per site per 50 million years (19). By superimposing this rate on my data, I calculated the time of acquisition, presumably by the common ancestor of Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae, to be about 13 to 26 million years ago, in the Miocene epoch of the Tertiary period.

Two closely related aphids, Y. tokyoensis and Y. hirayamae, contained both Buchnera spp. and YSMS. In these two species, the levels of genetic divergence of YSMS and Buchnera spp. were substantially similar based on the 16S rDNA sequences. Taking into account the fact that YSMS infected 100% of the individuals in local populations of Y. tokyoensis without detectable genetic divergence, it is likely that Buchnera spp. and YSMS were acquired by and descended from the common ancestor of the extant host species solely via vertical transmission throughout the evolution and speciation of the genus Yamatocallis. However, an alternative possibility cannot be ruled out, namely, that YSMS has occasionally been transmitted horizontally but has shown strict host specificity for the genus Yamatocallis. To test which of these hypotheses is more appropriate, molecular phylogenetic analysis of YSMS and host aphids from more populations and species of the genus must be conducted to examine whether cocladogenesis is observed for them.

In the endosymbiotic system of aphids, the genus Buchnera is highly conserved, is essential for the life and reproduction of the host, and is believed to have had an ancient evolutionary origin. Molecular phylogenetic estimates suggest that the endosymbiosis may be more than 100 million years old (19, 24). In contrast, some S-symbionts of aphids, such as those found in A. pisum, are not fixed in host populations, sometimes have negative effects on the life and reproduction of their hosts, and are thought to be facultative endosymbiotic companions with a recent evolutionary origin (4, 6, 15, 16, 22). Interestingly, YSMS of Yamatocallis spp., which is described in this study and is conserved in a host genus, can be considered an intermediate between the essential mutualist and facultative associates. Further studies on endosymbionts of this kind should provide insight into how parasitism, commensalism, and mutualism in endosymbiotic associations have evolved.

Acknowledgments

I thank A. Sugimura, S. Kumagai, and K. Sato for technical and secretarial assistance and T. Wilkinson for reading the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Industrial Science and Technology Frontier program “Technological Development of Biological Resources in Bioconsortia” of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumann P, Baumann L, Lai C-Y, Rouhbakhsh D, Moran N A, Clark M A. Genetics, physiology and evolutionary relationships of the genus Buchnera: intracellular symbionts of aphids. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:55–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackman R L, Eastop V F. Aphids on the world's trees. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchner P. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. New York, N.Y: Interscience; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen D Q, Purcell A H. Occurrence and transmission of facultative endosymbionts in aphids. Curr Microbiol. 1997;34:220–225. doi: 10.1007/s002849900172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D Q, Campbell B C, Purcell A H. A new Rickettsia from a herbivorous insect, the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) Curr Microbiol. 1996;33:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s002849900086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen D Q, Montllor C B, Purcell A H. Fitness effects of two facultative endosymbiotic bacteria on the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, and the blue alfalfa aphid, A. kondoi. Entomol Exp Appl. 2000;95:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darby A C, Birkle L M, Turner S L, Douglas A E. An aphid-borne bacterium allied to the secondary symbionts of whitefly. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;1235:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon A F G. Aphid ecology. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas A E. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria, Buchnera. Annu Rev Entomol. 1998;43:17–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukatsu T. Acetone preservation: a practical technique for molecular analysis. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:1935–1945. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukatsu T, Ishikawa H. Occurrence of chaperonin 60 and chaperonin 10 in primary and secondary bacterial symbionts of aphids: implications for the evolution of an endosymbiotic system in aphids. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:568–577. doi: 10.1007/BF00556361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukatsu T, Ishikawa H. Differential immunohistochemical visualization of the primary and secondary intracellular symbiotic bacteria of aphids. Appl Entomol Zool. 1998;33:321–326. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukatsu T, Nikoh N. Endosymbiotic microbiota of the bamboo pseudococcid Antonina crawii (Insecta, Homoptera) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:643–650. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.2.643-650.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukatsu T, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi Y. Specific detection of intracellular symbiotic bacteria of aphids by oligonucleotide-probed in situ hybridization. Appl Entomol Zool. 1998;33:461–472. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukatsu T, Nikoh N, Kawai R, Koga R. The secondary endosymbiotic bacterium of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Insecta: Homoptera) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2748–2758. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.7.2748-2758.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukatsu T, Tsuchida T, Nikoh N, Koga R. Spiroplasma symbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Insecta: Homoptera) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1284–1291. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1284-1291.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houk E J, Griffiths G W. Intracellular symbiotes of Homoptera. Annu Rev Entomol. 1980;25:161–187. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa H, Yamaji M. Symbionin, an aphid endosymbiont-specific protein. I. Production of insects deficient in symbiont. Insect Biochem. 1985;15:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moran N A, Munson M A, Baumann P, Ishikawa H. A molecular clock in endosymbiotic bacteria is calibrated using the insect hosts. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1993;253:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran N A. Accelerated evolution and Muller's rachet in endosymbiotic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2873–2878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohtaka C, Ishikawa H. Effects of heat treatment on the symbiotic system of an aphid mycetocyte. Symbiosis. 1991;11:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandström J P, Russell J A, White J P, Moran N A. Independent origins and horizontal transfer of bacterial symbionts of aphids. Mol Ecol. 2001;10:217–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unterman B M, Baumann P, McLean D L. Pea aphid symbiont relationships established by analysis of 16S rRNAs. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2970–2974. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.2970-2974.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Von Dohlen C D, Moran N A. Molecular data support a rapid radiation of aphids in the Cretaceous and multiple origins of host alteration. Biol J Linn Soc. 2000;71:689–717. [Google Scholar]