Abstract

Background

Anthropogenic activities have increased the inputs of atmospheric reactive nitrogen (N) into terrestrial ecosystems, affecting soil carbon stability and microbial communities. Previous studies have primarily examined the effects of nitrogen deposition on microbial taxonomy, enzymatic activities, and functional processes. Here, we examined various functional traits of soil microbial communities and how these traits are interrelated in a Mediterranean-type grassland administrated with 14 years of 7 g m−2 year−1 of N amendment, based on estimated atmospheric N deposition in areas within California, USA, by the end of the twenty-first century.

Results

Soil microbial communities were significantly altered by N deposition. Consistent with higher aboveground plant biomass and litter, fast-growing bacteria, assessed by abundance-weighted average rRNA operon copy number, were favored in N deposited soils. The relative abundances of genes associated with labile carbon (C) degradation (e.g., amyA and cda) were also increased. In contrast, the relative abundances of functional genes associated with the degradation of more recalcitrant C (e.g., mannanase and chitinase) were either unchanged or decreased. Compared with the ambient control, N deposition significantly reduced network complexity, such as average degree and connectedness. The network for N deposited samples contained only genes associated with C degradation, suggesting that C degradation genes became more intensely connected under N deposition.

Conclusions

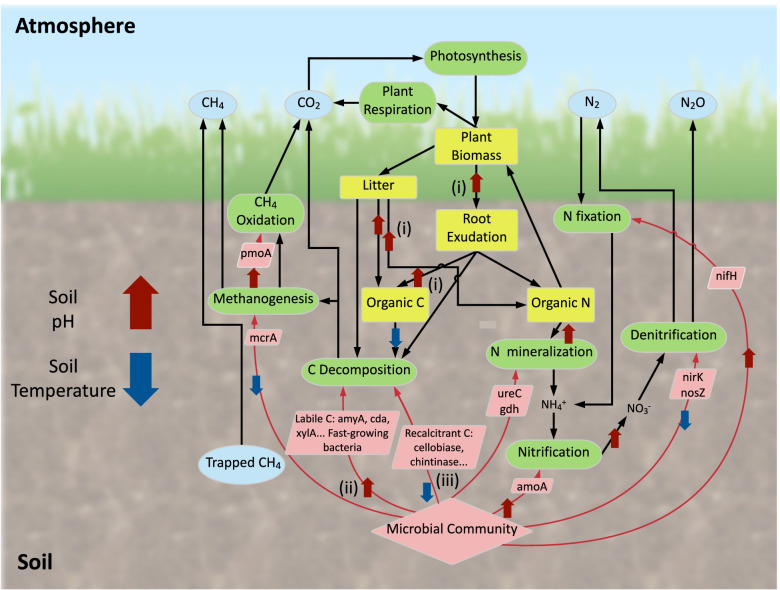

We propose a conceptual model to summarize the mechanisms of how changes in above- and belowground ecosystems by long-term N deposition collectively lead to more soil C accumulation.

Video Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40168-022-01309-9.

Keywords: Soil microbial community, Nitrogen deposition, High-throughput sequencing, GeoChip, Global change

Background

Anthropogenic activities have dramatically increased the production of reactive N worldwide, likely at levels exceeding all of the natural terrestrial N sources combined [1]. Increased N inputs into the environment have many consequences, including marine and freshwater eutrophication, marine acidification, air pollution, and changes in ecosystem functioning and composition [2, 3]. Several studies have shown that soil microbial taxonomic diversity is either unaltered or decreased with N deposition, often with a higher relative abundance of Proteobacteria and a lower relative abundance in Acidobacteria [4–7]. N depositions, especially those at high levels (> 50 kg ha−1 year−1 of N) or over long durations, often decrease microbial biomass [8, 9] and soil respiration [10]. However, the activities of hydrolases can increase with N deposition, showing preferential degradation of labile C pools [11, 12]. By contrast, recalcitrant C-degrading enzymes such as phenol oxidases remain unchanged [5, 11] or decrease [13, 14], suggesting that an increase in labile C pools might ameliorate microbial requirements for obtaining N from recalcitrant C pools, which are richer in the N content than labile C [15]. Additionally, N deposition often increases N cycling rates, as reported for gross N mineralization, gross and potential nitrification or ammonia and nitrite oxidation, and potential denitrification [16–18]. N deposition can also alter the abundances of key microbial groups involved in N cycling, stimulating some bacterial but not archaeal ammonia oxidizers and increasing the abundance of some nitrite oxidizers such as Nitrobacter but not Nitrospira [19–23]. However, N deposition can increase, decrease, or do not change the abundances of N fixation groups in different environments such as cold region soils, forest soils, and rhizosphere [24–26].

Plant growth is generally N limited in annual grasslands of California, USA [27]. Thus, N deposition typically induces large changes in plant and soil microbial community composition [7, 28–30]. Although many studies have examined the responses of below- and aboveground ecosystems to N addition, much remains unknown how responses of a broad range of microbial functional groups and interactions are related to soil C and N dynamics, which restricts our understanding of the effect of long-term N deposition on soil microbial communities and soil functioning in natural grasslands. To address it, we carried out a 14-year N (in the form of Ca(NO3)2) deposition experiment in a multifactor field study in a California annual grassland located near Stanford, CA, USA (Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment, JRGCE) [31], which is one of the longest experiments of N deposition. The JRGCE is designed to assess grassland responses to single and multiple drivers of global changes, including elevated CO2, warming, atmospheric nitrate deposition, and enhanced precipitation. Each experimental plot at the JRGCE is circular, 2 m in diameter, and equally divided into four quadrants of 0.78 m2 [31]. The CO2 and warming treatments are applied at the plot level, and N and water treatments are applied at the quadrant level in a full factorial design, resulting in 16 treatments with eight replicates of each. However, an experimental fire burned four replicate blocks in 2011. Therefore, only the four unburned blocks (a total of 64 samples) are used in this study.

We used 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (Illumina MiSeq) and functional gene array (GeoChip 4.6) to compare the microbial community compositions (both taxonomic diversity and functional diversity) between control and N deposited samples. Our objectives are to assess the long-term effect of N deposition on a broad range of soil bacterial taxa, major functional genes associated with C and N cycling, and how these genes are co-occurring. We also aim to analyze how the changes in the taxonomic and functional gene compositions are related to the changes in environmental attributes. Since N deposition typically stimulates the primary productivity of plants and consequently fresh C input to soil [8, 32, 33], we hypothesize that fast-growing bacteria would be enriched and that functional genes associated with labile C degradation would be stimulated by N deposition, leading to higher metabolic capacities for soil C stabilization. Accordingly, we hypothesize that N deposition will affect associations among functional groups as characterized by network analysis. Since previous results at our study site have shown that soil ammonium concentrations increase with Ca(NO3)2 deposition over the long term owing to N turnover and enhanced N mineralization [17, 22, 34], our third hypothesis is that functional microbial groups associated with N cycling would be stimulated. More precisely, we postulate that microbial groups that perform better under higher N availability, e.g., bacterial ammonia oxidizers and Nitrobacter-like nitrite oxidizers [19–21], would be particularly stimulated.

Materials and methods

Site and soil description

The experiment was conducted at the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment (JRGCE) site in coastal central California, USA. It has been operated on an annual grassland under a Mediterranean-type climate at the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve (37° 24′ N, 122° 13′ W) beginning in October 1998. The plant community comprises annual and perennial grasses and forbs [29]. The soil is a fine Haploxeralf developed from Franciscan complex alluvium sandstone.

Soil samples were collected in April 2012, i.e., 14 years after the experiment began. On April 26 and 27, 2012, we collected soil cores (5 cm diameter × 7 cm deep) to generate each of 32 control samples and 32 long-term N deposited samples. Soil samples were thoroughly mixed and sieved through a 2-mm mesh to remove visible roots and rocks and stored at −80 °C before DNA extraction, or at −20°C before a range of soil geochemical measurements.

DNA extraction, purification, and quantification

DNA was extracted from 5 g of well-mixed soil using a freeze grinding mechanical lysis method as previously described [35]. DNA was then purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by extractions with phenol and chloroform and precipitation with butanol. DNA quality was determined by light absorbance ratio at wavelengths of 260/280nm and 260/230nm using a Nanodrop (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). Then, DNA concentrations were quantified with PicoGreen [36] using a FLUOstar Optima microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Jena, Germany).

16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and data processing

To study the diversity of the bacterial community, we targeted the V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA genes. Briefly, we carried out PCR amplification using the primer pair 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) [37] and then sequenced the PCR products by 2 × 250 bp paired-end sequencing on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). We processed raw sequence data on the Galaxy platform with several software tools [36]. First, we carried out demultiplexing to remove PhiX sequences and sorted sequences to the appropriate samples based on their barcodes, allowing for 1 or 2 mismatches. These sequences were then trimmed based on quality scores using Btrim [38], and paired-end reads were merged into full-length sequences with FLASH [39]. After removing sequences of less than 200 bp or containing ambiguous bases, we discarded chimeric sequences based on the prediction by Uchime [40] using the reference database mode. We clustered sequences with Uclust [41] at the 97% similarity level. Final OTUs were generated based on the clustering results, and taxonomic annotation of individual OTU was assigned based on representative sequences using RDP’s 16S rRNA gene classifier [42]. The rRNA operon copy number for each OTU was estimated through the rrnDB database based on its closest relative with a known rRNA operon copy number [43]. The abundance-weighted mean rRNA operon copy number of each sample was then calculated according to a previous publication [36].

GeoChip hybridization and raw data processing

We carried out DNA hybridization with GeoChip 4.6, as previously described [44, 45]. In brief, DNA was labeled with Cy-3 fluorescent dye using a random priming method, purified, and dried at 45 °C (SpeedVac, ThermoSavant, Milford, MA, USA). DNA was hybridized with GeoChip 4.6 at 42 °C for 16 h on an MAUI hybridization station (BioMicro, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), which was scanned with a NimbleGen MS 200 Microarray Scanner (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

As previously described [44, 45], we processed raw GeoChip data using the following steps: (i) removing the spots with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) less than 2.0; (ii) log-transforming the data and then, on each microarray, dividing them by the mean intensity of all the genes; and (iii) removing genes detected only once in four replicates.

Network analyses

Using microbial functional genes associated with C and N cycling, we constructed association networks by an in-house pipeline (http://ieg2.ou.edu/MENA) for both control and long-term N deposited samples. Only genes detected in more than 24 of the 32 biological replicates were kept for network construction. We used random matrix theory (RMT) to automatically determine the similarity threshold (St) among genes before network construction since RMT can distinguish system-specific, nonrandom associations from random gene associations [46]. Similarity matrices were calculated based on Spearman rank correlation. The network topological properties, including the total number of nodes, the total number of links, the proportion of positive and negative links, average degree (avgK), centralization of degree (CD), average clustering coefficient (avgCC), harmonic geodesic distance (HD), centralization of betweenness (CB), centralization of stress centrality (CS), and network density and modularity, were computed. The networks were graphed using Gephi v. 0.92 [47].

Measurements of vegetation and soil attributes

We collected plant aboveground biomass from a 141-cm2 area of each 7853 cm2 quadrant 1 day before soil sampling in April 2012. The biomass of individual plant species was combined into functional groups, including the biomass of annual grasses (AG), perennial grasses (PG), annual forbs (AF), and perennial forbs (AP), plus total aboveground litter mass. We estimated root biomass by separating roots from two soil cores (2.5-cm diameter by 15-cm depth) taken in the same area used for the aboveground biomass harvest.

We measured hourly soil temperature during 2012 using thermocouples installed at a depth of 2 cm. Soil moisture was measured by drying 10 g of freshly collected soil in a 105°C oven for 1 week, and soil pH using 5 g of soil dissolved in distilled water. The total soil C (TC) and N (TN) concentrations were determined by combustion analysis on a Carlo Erba Strumentazione Model 1500 Series I analyzer at the Carnegie Institution for Science, Department of Global Ecology. To measure soil NH4+ and NO3− concentrations, we suspended 5 g of soil in a 2 M KCl solution and then measured filtered extracts colorimetrically using a SEAL Automated Segmented Flow analyzer in the Loyola University, Chicago, IL, USA. We measured soil CO2 efflux of each sample three times by a closed chamber method in April 2012 as previously described [48], where a LiCOR LI-6400 portable photosynthesis system and LI6400-09 Soil Flux Chamber (LiCOR, Lincoln, NE, USA) were used.

Statistical analyses

We used a permutation paired t-test to determine statistically significant differences between relative abundances of the taxonomic markers, relative abundances of functional genes, and environmental attribute measurements. We compared the composition of microbial communities using three non-parametric dissimilarity tests, including permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Adonis), analysis of similarities (Anosim), and multi-response permutation procedure (Mrpp). Shannon index (H’) was used to estimate the taxonomic or functional gene diversity. We performed detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) to assess overall changes in the microbial community composition and Mantel tests to detect correlations between quantitative measures of microbial community dissimilarity and environmental attributes. To examine the effect of N deposition on individual taxonomic group, functional gene category, or family, we used response ratios to quantify the abundance change by treatment. We used the R package “DESeq2” [49] to calculate the differential abundance (log2-fold change in the relative abundance of each OTU) for N deposition samples as compared with the control samples. We filtered out OTUs that were sparsely represented across all of the samples (i.e., OTUs for which the DESeq2-normalized count across all of the samples (“baseMean”) was < 0.8). Given the high number of mean comparisons and correlations tested, we adjusted the P-values with the Benjamini and Hochberg correction method. We considered adjusted P < 0.050 to be statistically significant unless otherwise indicated. All statistical analyses were performed by R version 3.0.1 (R Core Team 2013).

Results

Taxonomic composition of bacterial communities

The N deposition treatment in the form of Ca(NO3)2 has been applied twice per year throughout the duration of the experiment. Specifically, 2 g N m−2 as a Ca(NO3)2 solution was applied at the first rains (November) to mimic a periodic N flush, then 5 g m−2 N as the slow-release pellet was applied in January to mimic constant atmospheric N deposition [29, 31, 50, 51]. Earlier studies showed that N deposition produced the largest effects on the JRGCE ecosystem [50, 51]. Therefore, we focused on the microbial responses to N deposition applied on top of other climate change drivers after 14 years since the experiment began. The main N effects on microbial communities were largely similar between n = 32 and n = 4 (see the rest of the “Results” and “Discussion” sections for details), so we used all samples to improve statistical power.

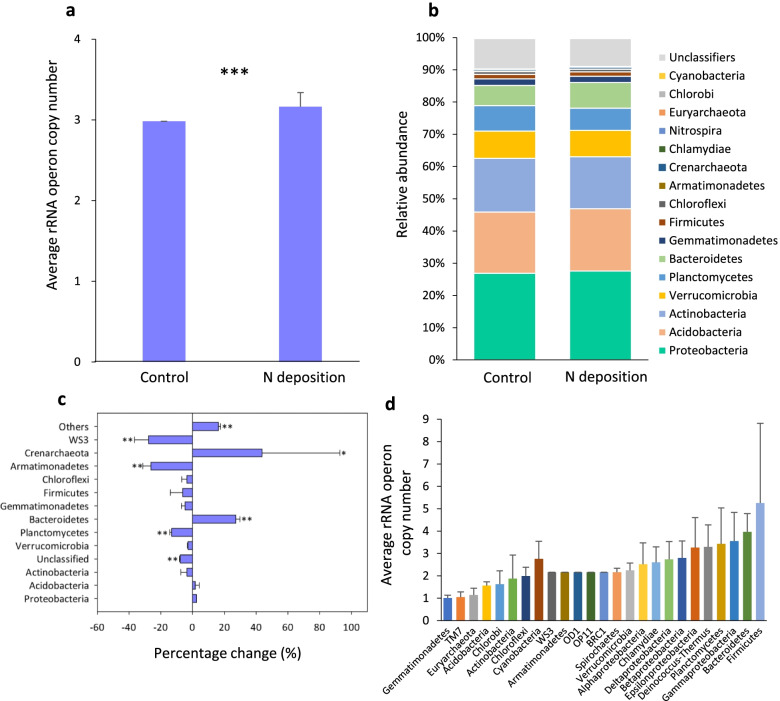

A total of 482,081 sequence reads of the 16S rRNA gene amplicons were obtained from all 64 samples, ranging from 29,275 to 82,066 reads per sample. After resampling at 29,275 sequence reads for all samples, 26,997 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were generated at the threshold of 97% nucleotide identity. Using three non-parametric statistical analyses (Anosim, Adonis, and Mrpp), we found that N deposition induced significant changes in the overall taxonomic composition of soil bacterial communities (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1). Additionally, N deposition increased the estimated abundance-weighted average rRNA operon copy number of significantly changed OTUs for each sample from 2.98 ± 0.21 to 3.16 ± 0.17 (P < 0.001, Fig. 1a). However, the α-diversity of the bacterial community was unaltered by N deposition (Additional file 1: Table S2). The responses of the relative abundances of the bacterial phyla to N deposition across the eight factorial combinations of CO2, warming, and precipitation (N = 32) were generally similar to those observed when considering only N deposition under ambient CO2, no warming, and ambient precipitation (N = 4, Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Table 1.

The effects of N deposition on taxonomic and functional compositions of microbial communities, calculated with Bray-Curtis distance

| Statistical approaches | Taxonomic | Functional | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anosim | R | 0.264 | 0.048 |

| P§ | 0.001§ | 0.025 | |

| Adonis | F | 0.074 | 0.031 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.054 | |

| Mrpp | δ | 0.463 | 0.256 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.035 |

§Significantly (P < 0.050) changed values are shown in bold

Fig. 1.

a The abundance-weighted average rRNA operon copy number of significantly changed OTUs in control and N deposited samples. b Relative abundance of bacterial phylum in control and N deposited samples. c The percent change in relative abundances of microbial phyla induced by N deposition. d The average estimated rRNA copy number of OTUs derived from each phylum. Error bars indicate standard errors. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *P < 0.050; **P < 0.010

The most abundant bacterial taxa were Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Planctomycetes, and Bacteroidetes, in decreasing order of relative abundance (Fig. 1b). The relative abundances of r-Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes were significantly increased with N deposition (Fig. 1c and Additional file 1: Fig. S2), with a higher estimated rRNA copy number (3.96 ± 0.82 in N deposited samples vs. 3.55 ± 1.29 in control samples, Fig. 1d). In contrast, the relative abundances of Deltaproteobacteria, Planctomycetes, and most classes of Acidobacteria decreased with N deposition (Additional file 1: Fig. S2), with their estimated rRNA copy number (1.56 ± 0.17) being much lower than the average rRNA copy number of all OTUs (2.51 ± 1.28) (Fig. 1d). At the finer taxonomic resolution, relative abundances of Mycobacterium and Anaeromyxobacter significantly decreased with N deposition, while OTUs affiliated with Pseudomonas and 99 out of 124 Bacteroidetes OTUs significantly increased (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Regarding nitrifiers, we identified a total of 76 ammonia-oxidizing bacterial OTUs belonging to the genera Nitrosomonas (1 OTU) and Nitrosospira (75 OTUs) and 77 nitrite-oxidizing bacteria belonging to the genera Nitrobacter (48 OTUs) and Nitrospira (29 OTUs). Relative abundances of Nitrosospira and Nitrospira were both significantly increased by N deposition, while the relative abundance of Nitrobacter remained unchanged (Additional file 1: Fig. S3).

Functional composition of microbial community

We detected a total of 60,887 microbial functional genes by GeoChip. Similar to observations at the taxonomic level, N deposition induced significant changes in overall functional compositions of the soil microbial communities (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1), but the α-diversity of the soil microbial community based on functional genes remained unaltered (Additional file 1: Table S2). The responses of the relative abundances of the functional genes to N deposition treatment across the eight factorial combinations of CO2, warming, and precipitation (N = 32) were generally similar to those observed when considering only N deposition under ambient CO2, no warming, and ambient precipitation (N = 4) (Fig. 1).

C cycling

We detected a total of 20,079 genes associated with C cycling. Most of the C fixation genes that significantly responded to N deposition increased in relative abundance except mcm encoding methyl malonyl-CoA mutase and mmce encoding methyl malonyl-CoA epimerase (associated with 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle), which decreased in relative abundance (Additional file 1: Fig. S4).

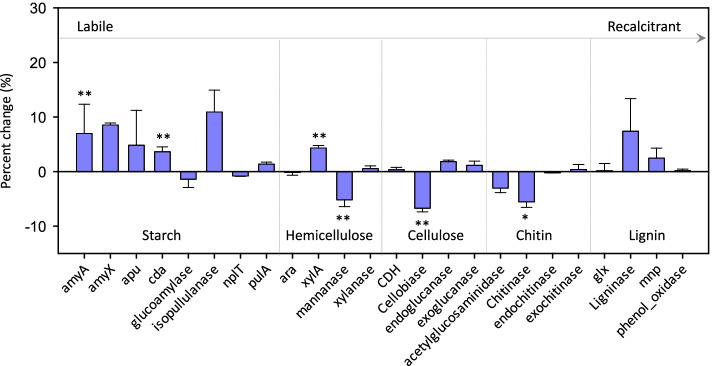

C degradation genes associated with different substrates showed disparate responses. The relative abundances of amyA encoding α-amylase, cda encoding cytidine deaminase associated with starch degradation, and xylA encoding xylose isomerase associated with hemicellulose degradation increased with N deposition (Fig. 2). In contrast, the relative abundances of mannanase gene associated with hemicellulose degradation, cellobiase gene associated with cellulose degradation, and chitinase gene associated with chitin degradation decreased with N deposition. Genes associated with lignin degradation, such as glx encoding glyoxal oxidase, ligninase, mnp encoding manganese peroxidase, and phenol oxidase, remained unchanged. That is, N deposition increased the relative abundances of genes associated with chemically labile C degradation, while it either decreased or had no effect on the relative abundance of genes associated with more chemically recalcitrant C degradation.

Fig. 2.

Changes in C cycling gene abundances. The percent change in the relative abundance of C degradation genes by N deposition is calculated as 100*((mean value in N deposited samples/mean value in control samples) – 1). Mean values and standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *P < 0.050; **P < 0.010

The methanogenesis gene mcrA decreased with N deposition (Additional file 1: Fig. S5). In contrast, the abundance of the methane-oxidation gene pmoA increased with N deposition, while other methane-oxidation genes mmoX and hdrB remained unchanged.

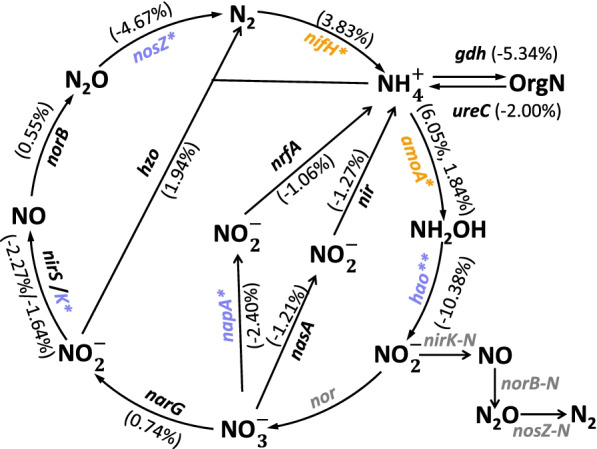

N cycling

Relative abundances of several functional genes associated with N cycling were reduced by N deposition (Fig. 3), including nirK encoding Cu-like nitrite reductase and denitrification gene nosZ1 encoding nitrous oxide reductase, along with nitrate reduction gene napA encoding nitrate reductase. In contrast, amoA encoding ammonia monooxygenase increased in relative abundance with N deposition. The significantly increased amoA genes included archaeal amoA derived from Crenarchaeota (GeneID 218938119, 82570877, 146146994, 164614053, and 124294977) and bacterial amoA derived from the Nitrosomonadaceae and Nitrospiraceae (GeneID 124514869, 161729059, and 78057472) (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). The relative abundance of N2 fixation gene nifH encoding nitrogenase also increased with N deposition.

Fig. 3.

Changes in N cycling gene abundances. The percent change in brackets for each gene is calculated as 100*(( mean value in N deposited samples/mean value in control samples) – 1). Orange and blue represent increases and decreases in gene relative abundance in response to N deposition, respectively. Gray-colored genes are not targeted by GeoChip. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *P < 0.050; **P < 0.010

P cycling

The relative abundance of polyphosphate kinase gene ppk associated with polyphosphate synthesis, phytase genes associated with phytic acid hydrolysis, and exopolyphosphatase gene ppx associated with polyphosphate degradation remained unchanged (Additional file 1: Fig. S5).

The network analysis of C and N cycling genes

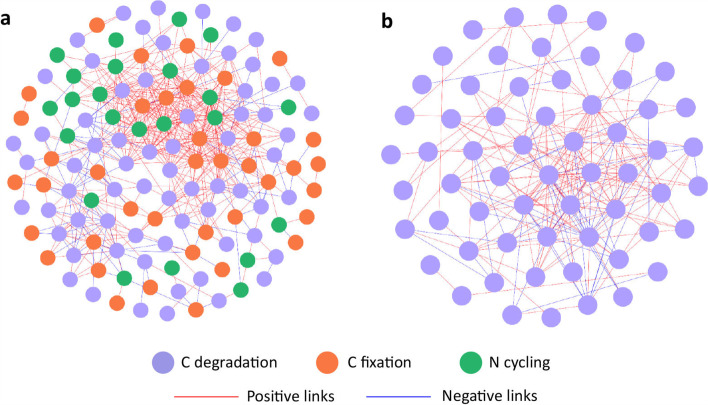

Association networks were constructed to de-convolute complex relationships for functional genes involved in C degradation, C fixation, and N cycling (Fig. 4). The gene networks for both control and N deposited samples had general topological properties of scale-free (power-law R2 of 0.747~0.914), small world (average path distance of 2.94~3.28), and hierarchy (average clustering coefficient of 0.39~0.51, Additional file 1: Table S4). Although the nodes and links in the network for control samples outnumbered those in the network for N deposited samples (Additional file 1: Table S4), positive links accounted for over half of all links in both networks, suggesting that more microbial C and N cycling genes tended to be co-occurring rather than co-excluding. Although we used the same similarity threshold to construct both networks, topological properties, including average degree and connectedness, were lower in the network of N deposited samples than that of control samples, revealing a less connected network structure. Compared to the network of control samples that contained diverse microbial functional genes associated with C degradation, C fixation, and N cycling, the network of N deposited samples contained only genes associated with C degradation (Fig. 4), suggesting that C degradation genes were intensely connected under N deposition. Consistently, the modularity of the N deposited network was lower than that of the control network (Additional file 1: Table S4), implying fewer coherently changing functional units with N deposition.

Fig. 4.

Association networks of microbial functional genes associated with C degradation, C fixation, and N cycling in a control samples and b N deposited samples. C degradation genes are shown in green circles, C fixation genes are shown in blue circles, and N cycling genes are shown in red circles. Positive links between genes are in red and negative links are in blue

Linkages between environmental attributes and microbial community

Long-term N deposition increased the growth of aboveground biomass and the amount of litter but had no significant effect on belowground biomass (Additional file 1: Table S5). N deposition also increased soil CO2 efflux rates in April 2012 from 5.04 to 6.03 μmol m−2 s−1 (P = 0.019). Soil temperature was decreased owing to the shading effect from higher aboveground biomass. Soil pH was increased (P = 0.012) from 6.20 to 6.34 by N deposition. Soil NO3− was also increased from 79.7 to 612 mg/L and soil NH4+ was increased from 666 to 1001 mg/L, in addition to the increase of soil TC and TN (P = 0.001).

Soil pH and the biomass of annual grasses correlated with quantitative measures of taxonomic composition dissimilarity (Additional file 1: Table S6). By contrast, perennial forb biomass and plant litter correlated with quantitative measures of functional composition dissimilarity. Additionally, soil TC marginally correlated with quantitative measures of both taxonomic and functional composition dissimilarity.

Discussion

In the present study, the observed alteration of soil and plant attributes in response to N deposition led to significant changes in the above- and belowground communities. On the one hand, higher aboveground biomass and litter increased soil nutrient input (mechanism i in Fig. 5). On the other hand, overall taxonomic and functional compositions of the belowground soil bacterial communities were also significantly changed, even when considered across different levels of CO2, warming, and precipitation (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Therefore, the 32 samples used here both improve the statistical power and identify trends that are valid across the range of climate change scenarios tested at Jasper Ridge.

Fig. 5.

A conceptual model of the effects of N deposition on the terrestrial ecosystem processes. Blue oval frames represent greenhouse gas pools, yellow square frames represent material pools, green frames represent biological processes, pink rhomboid frames represent microbial functional genes, and pink rhombus frames represent microbial communities. Thick black arrows indicate material flows. Microbial mediation of soil biogeochemical process is marked by thin arrows in red and labeled with a “+” or “-” if increases or decreases in gene abundance are observed in this study. “?” represents uncertain microbial feedback. The pink upward arrow indicates the increase of soil pH, and the blue downward arrow indicates the decrease of soil temperature. The (i), (ii), and (iii) mechanisms are labeled near the pathway

Long-term N deposition alters the bacterial taxonomic composition

Our results verify previous findings from long-term N amendment experiments in a Minnesota semiarid grassland and Michigan agricultural land showing significant changes in the 16S rRNA gene-based soil microbial community composition [5, 7]. More particularly, the rRNA operon copy number is used as a functional trait related to the maximal bacterial growth rate [52, 53]. Our results concerning the estimated rRNA operon copy number support our hypothesis that N deposition shifts the bacterial community from slow- to fast-growing taxa (Fig. 1) [7]. It is consistent with richer soil nutrients induced by long-term N deposition [54], leading to increased litter mass, soil TC, TN, and NO3− concentrations (mechanism ii in Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Table S5). Similarly, a previous study has shown that ammonium nitrate deposition also decreases the relative abundances of many taxa from Acidobacteria, which have low rRNA copy numbers (Fig. 1d) and are thought to be slow-growing [55]. Furthermore, previous reports have shown that ammonium or urea depositions increase the relative abundances of taxa such as Bacteroidetes and r-Proteobacteria [3, 7, 56] characterized by higher estimated rRNA copy number (Fig. 1d) regarded as fast-growing taxa [57]. Together, it seems that the effects of long-term N deposition on microbial taxonomic composition are independent of N form, likely due to the overall N cycling in the soil-plant system so that the long-term N deposition treatment in an N form may ultimately increase the availability of other N forms as well. For instance, nitrate deposition in the JRGCE has been reported to increase soil ammonium concentrations (this trend was observed here, but the effect was insignificant), reflecting N turnover and increased N mineralization [17, 22, 34].

The effect of long-term N deposition on microbial functional genes for soil C cycling

N deposition can significantly accelerate chemically labile C decomposition [58, 59]. Consistently, we have observed a significant increase in the relative abundance of the amyA gene (Fig. 2), which is among the most abundant genes, providing evidence for the preferential microbial utilization of labile C with N deposition. The significantly increased soil CO2 efflux (Additional file 1: Table S5), mediated by higher net primary productivity, was consistent with more labile C [48]. Additionally, N deposition can stabilize or even inhibit the decomposition of chemically recalcitrant C in soil [14, 60]. For instance, N deposition increases the activity of labile C-degrading enzymes but has no effect on or inhibits the activity of lignin-degrading enzymes [11]. Increased use of labile C and decreased use of recalcitrant C can result in soil C accumulation [5, 61]. Here, we observed that N deposition increased the relative abundance of genes associated with chemically labile C degradation but either decreased or had no effect on the relative abundance of genes associated with chemically recalcitrant C degradation (mechanisms ii and iii in Fig. 5). Therefore, N deposition at the JRGCE site is unlikely to induce a priming effect, i.e., fresh C input stimulating recalcitrant old soil organic C degradation [62], which would decrease soil C [63]. Overall, our results reveal a shift in the functional composition of the soil microbial community, which is likely favorable to soil C accumulation.

The effect of long-term N deposition on microbial functional genes linked to soil N cycling

N deposition has previously been shown to increase potential soil nitrification rate, gross N mineralization, and nitrifier abundances at the JRGCE [16, 17, 30]. Our study shows that some changes in the soil microbial community are consistent with increased nitrification, in particular with higher relative abundances of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria from the genera Nitrosospira and Nitrosomonas and the nitrite-oxidizing bacteria Nitrospira (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Similarly, N deposition also increases the relative abundances of the amoA gene involved in ammonia oxidation (Fig. 3), the rate-limiting step of nitrification in natural grassland [64]. Nitrification is often viewed as a process carried out by phylogenetically restricted microbial groups [65] and as an obligate activity for nitrifiers to derive energy for maintenance and growth. It explains the previous observation that changes in nitrification were associated with the abundances of nitrifiers [66], though such linkage was not detected elsewhere [19]. Generally, the correlation with nitrification holds for nitrifier abundances assessed either by quantitative PCR [67, 68] or by GeoChip [69, 70]. However, it is noticeable that the relative abundances of the hao gene encoding hydroxylamine oxidoreductase decreased with N deposition, which could be explained by the fact that conversion of hydroxylamine to nitrite is not the rate-limiting step of nitrification and that a partial decoupling between this step and other steps is possible.

Potential denitrification rates, measured as in situ N2O emission from the soil, increase with N deposition at our study site [71]. However, relative abundances of denitrification genes nirK and nosZ and nitrate reduction gene napA decreased with N deposition (Fig. 3), consistent with previous studies unveiling no correlation between denitrification rates and denitrifier abundances [68, 72]. Indeed, denitrification is a facultative process driven mostly by heterotrophs when they are under anaerobic conditions and with sufficient nitrate availability. However, denitrifiers are selected for different reasons than their denitrification capacity under other environmental conditions, often leading to weak activity-abundance relationships [73]. Moreover, the decoupling between denitrification and gene abundance might arise from the saturation of N supply (70 kg ha−1 year−1 of N) at our study site, since grasslands under Mediterranean climate type are saturated at N loads of 20 kg ha−1year−1 of N and nitrification and denitrification show nonlinear responses to N supply [74]. Furthermore, denitrification is a broad process carried out by phylogenetically diverse microbial groups [65], which may not be fully represented on GeoChip.

Long-term N deposition reduces microbial network complexity

Microbial functional genes and the microorganisms that harbor these genes carry out C and N cycling processes [75], and associations among these functional genes could partly, though hardly extensively, be captured by their abundance correlation-based networks [76]. In abundance correlation-based networks of functional genes, correlations can result from multiple mechanisms [77], including (i) metabolic dependence of the linked genes (e.g., links between C and N genes reflecting C/N coupled processes or links between N mineralization and nitrification genes resulting from stepwise N metabolism); (ii) their similar response to environmental variation or substrate availability (e.g., links between different C degradation genes associated with parallel mineralization of soil organic substrates of different molecular forms, or unified response of soil organic matter degradation to edaphic conditions); and/or (iii) their co-dependence on other factors (e.g., soil mineral Fe and Al) instead of direct association. These mechanisms are difficult to be teased apart only based on correlations. In our case, all of the above mechanisms are ecologically meaningful when considering the changes in microbial functional capacities and associations following N deposition. All of these mechanisms are hence potential causes of changes in sample variance that might influence connections and connectedness.

Our results showed that different microbial functional genes associated with C degradation, C fixation, and N cycling formed positive associations in the network of control samples (Fig. 4a), suggesting that microbial C and N processes were likely highly coupled when soil N availability was limited. Considering that growth conditions without N deposition were not optimal, degradation of soil organic matter represented an important source of N to microorganisms. As N availability increases, bacteria become less N and energy (electron acceptor) limited and thus preferentially mineralize progressively more bioavailable soil organic C [78]. Consistently, genes involved in C degradation remained more connected, without clear association with N-related genes (Fig. 4b).

Furthermore, increased N availability could diminish plant dependence on the mycorrhizal supply of organic N monomers [75], leading to more N allocation into plant tissues rather than microbes. As a result, associations among microbial genes involved in N cycling might be reduced. N deposition generally reduces N retention in the soil while increasing N leaching in different ecosystems [79, 80], which could also suppress soil N cycling processes mediated by microbial communities. Our results suggested that soil N availability might have an important role in shaping microbial networks of nutrient cycling and tends to decrease the coupling between N- and C-related functional genes.

Environmental filters for the soil microbial community

We have identified significant correlations between quantitative measures of microbial community dissimilarity and a set of key soil and plant properties using Mantel tests (Additional file 1: Table S6). The close linkage between soil pH and bacterial community taxonomic composition provides support to a growing body of literature showing that soil pH is the best predictor of soil bacterial diversity and composition, at least from kilometer to continental scales [81–83]. At smaller scales (e.g., in our study), soil pH is rather stable as compared to other soil environmental attributes like moisture or N availability. However, even slight deviations can result in marked changes in microbial communities in response to anthropogenic disturbances that can alter pH (here long-term N deposition) [84, 85].

Our results showed that aboveground plant biomass and litter correlated with quantitative measures of functional composition dissimilarity (Additional file 1: Table S6). Similarly, previous studies in grassland ecosystems have shown that at least 20% of the variation in soil microbial community composition was explained by plant attributes [44, 45]. Much of this variation may be caused by the indirect influence of aboveground plant biomass on microbial communities through enhanced production of dissolved organic C and the promotion of rhizosphere microbial populations [86, 87].

Conclusions

Overall, our results highlight the importance of investigating the joint responses of microbial functional groups involved in soil C and N dynamics to N availability. In response to long-term N deposition, the soil microbial community shifted toward a higher capacity to use chemically labile C (higher relative abundance of labile C degradation genes) in parallel with a higher relative abundance of fast-growing taxa. In contrast, genes associated with chemically recalcitrant C degradation remained unaltered or decreased. Additionally, the relative abundance of the amoA gene, characteristic of the first and rate-limiting step of nitrification in grasslands, increased as did plant biomass, whereas functional genes characterizing the denitrification process decreased with N deposition. It could give rise to a nitrification/denitrification balance favorable for N retention in the plant-soil system. As illustrated in the conceptual model presented in Fig. 5, our results suggest that N deposition favored soil C and N accumulation through three mechanisms: (i) increasing the nutrient source from plants by stimulating plant growth, as shown by increased aboveground biomass and litter; (ii) increasing the potential nutrient availability through the increased relative abundance of nutrient-cycling genes and increased fast-growing bacteria; and (iii) reducing the utilization of chemically recalcitrant C through decreased recalcitrant C degradation genes. Our results demonstrate that a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the response of the soil microbial community, in particular its functional traits and interactions, can help understand and predict the effects of N deposition on soil biogeochemical processes.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Comparison of taxonomic and functional β-diversity between and within treatments. Table S2. Effects of N deposition on microbial taxonomic and functional diversity, as assessed by Shannon index. Table S3. Significantly changed representative OTUs calculated by difference analyses. Table S4. Topological properties of microbial functional gene networks. Table S5. Summary of soil and vegetation attributes in control and N deposited samples. Table S6. Mantel tests for correlations between a range of environmental attributes and quantitative measures of microbial community dissimilarity. Fig. S1. Comparison of the percentage change by N deposition for (a) microbial phyla; (b) N cycling genes; and (c) C cycling genes between using 32 and 4 samples as biological replicates. Fig. S2. The percentage change in relative abundances of microbial class induced by long-term N deposition. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010. Fig. S3. The percentage change in the relative abundance of major microbial genera induced by long-term N deposition treatment. All selected genera are significantly changed by N deposition treatment as calculated by the response ratio analysis. Fig. S4. The percentage change in the relative abundance of genes associated with C fixation induced by N deposition, calculated as 100*(( mean value in N deposited samples/mean value in control samples) – 1). Mean values and standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010. The numbers in the figure represent the pathways of C fixation. (i) 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle, (ii) Bacterial microcompartments, (iii) Calvin cycle, and (iv) Reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle. Fig. S5. The percentage change in the relative abundance of genes associated with methane and phosphorus cycling genes induced by N deposition, calculated as 100*((mean value in N deposited samples/mean value in control samples) – 1). Mean values and standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010. Fig. S6. N deposition effects on amoA gene. The relative abundance of amoA is presented as the signal intensity difference between control and N deposited samples. Error bars represent standard errors. Blue bars represent genes derived from archaea (AOA), and pink bars represent genes derived from bacteria (AOB). Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment for site preservation and sampling assistance.

Abbreviations

- N

Nitrogen

- C

Carbon

- rRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- JRGCE

Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- SNR

Signal-to-noise ratio

- RMT

Random matrix theory

- St

Similarity threshold

- avgK

Average degree

- CD

Centralization of degree

- avgCC

Average clustering coefficient

- HD

Harmonic geodesic distance

- CB

Centralization of betweenness

- CS

Centralization of stress centrality

- AG

Annual grasses

- PG

Perennial grasses

- AF

Annual forbs

- AP

Perennial forbs

- TC

Total soil carbon

- TN

Total soil nitrogen

- Anosim

Analysis of similarities

- Mrpp

Multi-response permutation procedure

- DCA

Detrended correspondence analysis

- OTUs

Operational taxonomic units

- CO2

Carbon dioxide

- N2O

Nitrous oxide

Authors’ contributions

NRC, CBF, and YY designed the study. XM, YY, XG, JL, BAH, XLR, and JZ wrote the manuscript. KD, JG, YG, AN, and TY performed the experiments. XM, TW, QG, ZS, and MY analyzed the data. All authors have reviewed and agreed with the manuscript. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32161123002/41825016/41877048), the US Department of Energy, the US National Science Foundation (DEB-2129235/DEB-0092642/0445324), the Packard Foundation, the Morgan Family Foundation, the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (2019QZKK0503), and the French EC2CO Program (project INTERACT).

Availability of data and materials

GeoChip data are available online (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number GSE107168. MiSeq data are available in the NCBI SRA database with the accession number SRP126539.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xingyu Ma and Tengxu Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jizhong Zhou, Email: jzhou@ou.edu.

Yunfeng Yang, Email: yangyf@tsinghua.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gruber N, Galloway JN. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature. 2008;451(7176):293–296. doi: 10.1038/nature06592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend AR, Howarth RW, Bazzaz FA, Booth MS, Cleveland CC, Collinge SK, Dobson AP, Epstein PR, Holland EA, Keeney DR. Human health effects of a changing global nitrogen cycle. Front Ecol Environ. 2003;1(5):240–246. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0240:HHEOAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemergut DR, Townsend AR, Sattin SR, Freeman KR, Fierer N, Neff JC, Bowman WD, Schadt CW, Weintraub MN, Schmidt SK. The effects of chronic nitrogen fertilization on alpine tundra soil microbial communities: implications for carbon and nitrogen cycling. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10(11):3093–3105. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allison SD, Hanson CA, Treseder KK. Nitrogen fertilization reduces diversity and alters community structure of active fungi in boreal ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem. 2007;39(8):1878–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez KS, Craine JM, Fierer N. Consistent effects of nitrogen amendments on soil microbial communities and processes across biomes. Glob Chang Biol. 2012;18(6):1918–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02639.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell BJ, Polson SW, Hanson TE, Mack MC, Schuur EA. The effect of nutrient deposition on bacterial communities in Arctic tundra soil. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12(7):1842–1854. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fierer N, Lauber CL, Ramirez KS, Zaneveld J, Bradford MA, Knight R. Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 2012;6(5):1007–1017. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Greaver TL. A global perspective on belowground carbon dynamics under nitrogen enrichment. Ecol Lett. 2010;13(7):819–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treseder KK. Nitrogen additions and microbial biomass: a meta-analysis of ecosystem studies. Ecol Lett. 2008;11(10):1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssens IA, Luyssaert S. Carbon cycle: nitrogen’s carbon bonus. Nat Geosci. 2009;2(5):318–319. doi: 10.1038/ngeo505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry HA, Juarez JD, Field CB, Vitousek PM. Interactive effects of elevated CO2, N deposition and climate change on extracellular enzyme activity and soil density fractionation in a California annual grassland. Glob Chang Biol. 2005;11(10):1808–1815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001007.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutknecht JLM, Henry HAL, Balser TC. Inter-annual variation in soil extra-cellular enzyme activity in response to simulated global change and fire disturbance. Pedobiologia. 2010;53(5):283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pedobi.2010.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carreiro MM, Sinsabaugh RL, Repert DA, Parkhurst DF. Microbial enzyme shifts explain litter decay responses to simulated nitrogen deposition. Ecology. 2000;81(9):2359–2365. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2359:MESELD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saiya-Cork KR, Sinsabaugh RL, Zak DR. The effects of long term nitrogen deposition on extracellular enzyme activity in an Acer saccharum forest soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34(9):1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00074-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craine JM, Morrow C, Fierer N. Microbial nitrogen limitation increases decomposition. Ecology. 2007;88(8):2105–2113. doi: 10.1890/06-1847.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnard R, Le Roux X, Hungate BA, Cleland EE, Blankinship JC, Barthes L, Leadley PW. Several components of global change alter nitrifying and denitrifying activities in an annual grassland. Funct Ecol. 2006;20(4):557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niboyet A, Le Roux X, Dijkstra P, Hungate BA, Barthes L, Blankinship JC, Brown JR, Field CB, Leadley PW. Testing interactive effects of global environmental changes on soil nitrogen cycling. Ecosphere. 2011;2(5):art56. doi: 10.1890/ES10-00148.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niboyet A, Barthes L, Hungate BA, Le Roux X, Bloor JMG, Ambroise A, Fontaine S, Price PM, Leadley PW. Responses of soil nitrogen cycling to the interactive effects of elevated CO2 and inorganic N supply. Plant Soil. 2010;327(1):35–47. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0029-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonin M, Le Roux X, Poly F, Lerondelle C, Hungate BA, Nunan N, Niboyet A. Coupling between and among ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers in grassland mesocosms submitted to elevated CO2 and nitrogen supply. Microb Ecol. 2015;70(3):809–818. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma W, Jiang S, Assemien F, Qin M, Ma B, Xie Z, Liu Y, Feng H, Du G, Ma X, et al. Response of microbial functional groups involved in soil N cycle to N, P and NP fertilization in Tibetan alpine meadows. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;101:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Roux X, Bouskill NJ, Niboyet A, Barthes L, Dijkstra P, Field CB, Hungate BA, Lerondelle C, Pommier T, Tang J, et al. Predicting the responses of soil nitrite-oxidizers to multi-factorial global change: a trait-based approach. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:628. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Docherty KM, Balser TC, Bohannan BJM, Gutknecht JLM. Soil microbial responses to fire and interacting global change factors in a California annual grassland. Biogeochemistry. 2012;109(1):63–83. doi: 10.1007/s10533-011-9654-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assémien FL, Pommier T, Gonnety JT, Gervaix J, Le Roux X. Adaptation of soil nitrifiers to very low nitrogen level jeopardizes the efficiency of chemical fertilization in West African moist savannas. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10275. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Compton JE, Watrud LS, Porteous LA, Degrood S. Response of soil microbial biomass and community composition to chronic nitrogen additions at Harvard forest. For Ecol Manag. 2004;196(1):143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolb W, Martin P. Influence of nitrogen on the number of N2-fixing and total bacteria in the rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem. 1988;20(2):221–225. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(88)90040-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung J, Yeom J, Kim J, Han J, Lim HS, Park H, Hyun S, Park W. Change in gene abundance in the nitrogen biogeochemical cycle with temperature and nitrogen addition in Antarctic soils. Res Microbiol. 2011;162(10):1018–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harpole WS, Potts DL, Suding KN. Ecosystem responses to water and nitrogen amendment in a California grassland. Glob Chang Biol. 2007;13(11):2341–2348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01447.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zavaleta ES, Shaw MR, Chiariello NR, Mooney HA, Field CB. Additive effects of simulated climate changes, elevated CO2, and nitrogen deposition on grassland diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7650–7654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932734100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zavaleta ES, Shaw MR, Chiariello NR, Thomas BD, Cleland EE, Field CB, Mooney HA. Grassland responses to three years of elevated temperature, CO2, precipitation, and N deposition. Ecol Monogr. 2003;73(4):585–604. doi: 10.1890/02-4053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horz H-P, Barbrook A, Field CB, Bohannan BJM. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria respond to multifactorial global change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(42):15136–15141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406616101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw MR, Zavaleta ES, Chiariello NR, Cleland EE, Mooney HA, Field CB. Grassland responses to global environmental changes suppressed by elevated CO2. Science. 2002;298(5600):1987–1990. doi: 10.1126/science.1075312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia J, Wan S. Global response patterns of terrestrial plant species to nitrogen addition. New Phytol. 2008;179(2):428–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeBauer DS, Treseder KK. Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology. 2008;89(2):371–379. doi: 10.1890/06-2057.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niboyet A, Brown JR, Dijkstra P, Blankinship JC, Leadley PW, Le Roux X, Barthes L, Barnard RL, Field CB, Hungate BA. Global change could amplify fire effects on soil greenhouse gas emissions. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X, Zhang Q, Zheng M, Gao Y, Yuan T, Hale L, Van Nostrand JD, Zhou J, Wan S, Yang Y. Microbial functional traits are sensitive indicators of mild disturbance by lamb grazing. ISME J. 2019;13(5):1370–1373. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0354-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu L, Yang Y, Chen S, Jason Shi Z, Zhao M, Zhu Z, Yang S, Qu Y, Ma Q, He Z, et al. Microbial functional trait of rRNA operon copy numbers increases with organic levels in anaerobic digesters. ISME J. 2017;11(12):2874–2878. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kong Y. Btrim: a fast, lightweight adapter and quality trimming program for next-generation sequencing technologies. Genomics. 2011;98(2):152–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(21):2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(16):2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(16):5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoddard SF, Smith BJ, Hein R, Roller BR, Schmidt TM. rrnDB: improved tools for interpreting rRNA gene abundance in bacteria and archaea and a new foundation for future development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):D593. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y, Wu L, Lin Q, Yuan M, Xu D, Yu H, Hu Y, Duan J, Li X, He Z, et al. Responses of the functional structure of soil microbial community to livestock grazing in the Tibetan alpine grassland. Glob Chang Biol. 2013;19(2):637–648. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y, Gao Y, Wang S, Xu D, Yu H, Wu L, Lin Q, Hu Y, Li X, He Z, et al. The microbial gene diversity along an elevation gradient of the Tibetan grassland. ISME J. 2014;8(2):430–440. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Harris DP, Luo F, Xiong W, Joachimiak M, Wu L, Dehal P, Jacobsen J, Yang Z, Palumbo AV, et al. Snapshot of iron response in Shewanella oneidensis by gene network reconstruction. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In: Third international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media. May 17-20 2009. San Jose: DBLP; 10.13140/2.1.1341.1520.

- 48.Strong AL, Johnson TP, Chiariello NR, Field CB. Experimental fire increases soil carbon dioxide efflux in a grassland long-term multifactor global change experiment. Glob Chang Biol. 2017;23(5):1975–1987. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gutknecht JLM, Field CB, Balser TC. Microbial communities and their responses to simulated global change fluctuate greatly over multiple years. Glob Chang Biol. 2012;18(7):2256–2269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02686.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dukes JS, Chiariello NR, Cleland EE, Moore LA, Shaw MR, Thayer S, Tobeck T, Mooney HA, Field CB. Responses of grassland production to single and multiple global environmental changes. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(10):e319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roller BR, Stoddard SF, Schmidt TM. Exploiting rRNA operon copy number to investigate bacterial reproductive strategies. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(11):16160. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee ZM, Bussema C, 3rd, Schmidt TM. rrnDB: documenting the number of rRNA and tRNA genes in bacteria and archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D489–D493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu K, Chiariello NR, Tobeck T, Fukami T, Field CB. Nonlinear, interacting responses to climate limit grassland production under global change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(38):10589–10594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606734113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uksa M, Schloter M, Endesfelder D, Kublik S, Engel M, Kautz T, Kopke U, Fischer D. Prokaryotes in subsoil—evidence for a strong spatial separation of different phyla by analysing co-occurrence networks. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1269. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li C, Yan K, Tang L, Jia Z, Li Y. Change in deep soil microbial communities due to long-term fertilization. Soil Biol Biochem. 2014;75(Supplement C):264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fierer N, Bradford MA, Jackson RB. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology. 2007;88(6):1354–1364. doi: 10.1890/05-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waldrop MP, Zak DR, Sinsabaugh RL, Gallo M, Lauber C. Nitrogen deposition modifies soil carbon storage through changes in microbial enzymatic activity. Ecol Appl. 2004;14(4):1172–1177. doi: 10.1890/03-5120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bragazza L, Freeman C, Jones T, Rydin H, Limpens J, Fenner N, Ellis T, Gerdol R, Hájek M, Hájek T, et al. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition promotes carbon loss from peat bogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(51):19386–19389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neff JC, Townsend AR, Gleixner G, Lehman SJ, Turnbull J, Bowman WD. Variable effects of nitrogen additions on the stability and turnover of soil carbon. Nature. 2002;419(6910):915–917. doi: 10.1038/nature01136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geisseler D, Scow KM. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms – a review. Soil Biol Biochem. 2014;75:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bingeman CW, Varner J, Martin W. The effect of the addition of organic materials on the decomposition of an organic soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1953;17(1):34–38. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1953.03615995001700010008x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fontaine S, Bardoux G, Abbadie L, Mariotti A. Carbon input to soil may decrease soil carbon content. Ecol Lett. 2004;7(4):314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00579.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen J, Zhang L, Di H, He J. A review of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in Chinese soils. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:296. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schimel J. Ecosystem consequences of microbial diversity and community structure. In: Chapin FS, Körner C, editors. Arctic and alpine biodiversity: patterns, causes and ecosystem consequences. Ecological Studies, vol 113. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 1995. p. 239–54. 10.1007/978-3-642-78966-3_17.

- 66.Reed HE, Martiny JB. Microbial composition affects the functioning of estuarine sediments. ISME J. 2013;7(4):868–879. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Petersen DG, Blazewicz SJ, Firestone M, Herman DJ, Turetsky M, Waldrop M. Abundance of microbial genes associated with nitrogen cycling as indices of biogeochemical process rates across a vegetation gradient in Alaska. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(4):993–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Le Roux X, Schmid B, Poly F, Barnard RL, Niklaus PA, Guillaumaud N, Habekost M, Oelmann Y, Philippot L, Salles JF, et al. Soil environmental conditions and microbial build-up mediate the effect of plant diversity on soil nitrifying and denitrifying enzyme activities in temperate grasslands. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao M, Xue K, Wang F, Liu S, Bai S, Sun B, Zhou J, Yang Y. Microbial mediation of biogeochemical cycles revealed by simulation of global changes with soil transplant and cropping. ISME J. 2014;8:2045–2055. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu S, Wang F, Xue K, Sun B, Zhang Y, He Z, Van Nostrand JD, Zhou J, Yang Y. The interactive effects of soil transplant into colder regions and cropping on soil microbiology and biogeochemistry. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17(3):566. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brown JR, Blankinship JC, Niboyet A, van Groenigen KJ, Dijkstra P, Le Roux X, Leadley PW, Hungate BA. Effects of multiple global change treatments on soil N2O fluxes. Biogeochemistry. 2012;109(1-3):85–100. doi: 10.1007/s10533-011-9655-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Philippot L, Hallin S, Börjesson G, Baggs EM. Biochemical cycling in the rhizosphere having an impact on global change. Plant Soil. 2009;321(1):61–81. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9796-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Attard E, Recous S, Chabbi A, De Berranger C, Guillaumaud N, Labreuche J, Philippot L, Schmid B, Roux XL. Soil environmental conditions rather than denitrifier abundance and diversity drive potential denitrification after changes in land uses. Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17(5):1975–1989. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02340.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gomez-Casanovas N, Hudiburg TW, Bernacchi CJ, Parton WJ, DeLucia EH. Nitrogen deposition and greenhouse gas emissions from grasslands: uncertainties and future directions. Glob Chang Biol. 2016;22(4):1348–1360. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuypers MM, Marchant HK, Kartal B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(5):263. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou J, Deng Y, Luo F, He Z, Yang Y. Phylogenetic molecular ecological network of soil microbial communities in response to elevated CO2. MBio. 2011;2(4):e00122–e00111. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00122-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou J, Deng Y, Luo F, He Z, Tu Q, Zhi X, Relman DA. Functional molecular ecological networks. MBio. 2010;1(4):e00169–e00110. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00169-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kopáček J, Cosby BJ, Evans CD, Hruška J, Moldan F, Oulehle F, Šantrůčková H, Tahovská K, Wright RF. Nitrogen, organic carbon and sulphur cycling in terrestrial ecosystems: linking nitrogen saturation to carbon limitation of soil microbial processes. Biogeochemistry. 2013;115(1):33–51. doi: 10.1007/s10533-013-9892-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pandey A, Suter H, He J-Z, Hu H-W, Chen D. Nitrogen addition decreases dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in rice paddies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84(17):e00870–e00818. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00870-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Niu S, Classen AT, Dukes JS, Kardol P, Liu L, Luo Y, Rustad L, Sun J, Tang J, Templer PH, et al. Global patterns and substrate-based mechanisms of the terrestrial nitrogen cycle. Ecol Lett. 2016;19(6):697–709. doi: 10.1111/ele.12591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fierer N, Jackson RB. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(3):626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507535103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shen C, Xiong J, Zhang H, Feng Y, Lin X, Li X, Liang W, Chu H. Soil pH drives the spatial distribution of bacterial communities along elevation on Changbai Mountain. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;57:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(15):5111–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00335-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rousk J, Baath E, Brookes PC, Lauber CL, Lozupone C, Caporaso JG, Knight R, Fierer N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010;4(10):1340–1351. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fernandez-Calvino D, Baath E. Growth response of the bacterial community to pH in soils differing in pH. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;73(1):149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li H, Yang S, Xu Z, Yan Q, Li X, van Nostrand JD, He Z, Yao F, Han X, Zhou J, et al. Responses of soil microbial functional genes to global changes are indirectly influenced by aboveground plant biomass variation. Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;104:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hamilton EW, Frank DA. Can plants stimulate soil microbes and their own nutrient supply? Evidence from a grazing tolerant grass. Ecology. 2001;82(9):2397–2402. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[2397:CPSSMA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Comparison of taxonomic and functional β-diversity between and within treatments. Table S2. Effects of N deposition on microbial taxonomic and functional diversity, as assessed by Shannon index. Table S3. Significantly changed representative OTUs calculated by difference analyses. Table S4. Topological properties of microbial functional gene networks. Table S5. Summary of soil and vegetation attributes in control and N deposited samples. Table S6. Mantel tests for correlations between a range of environmental attributes and quantitative measures of microbial community dissimilarity. Fig. S1. Comparison of the percentage change by N deposition for (a) microbial phyla; (b) N cycling genes; and (c) C cycling genes between using 32 and 4 samples as biological replicates. Fig. S2. The percentage change in relative abundances of microbial class induced by long-term N deposition. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010. Fig. S3. The percentage change in the relative abundance of major microbial genera induced by long-term N deposition treatment. All selected genera are significantly changed by N deposition treatment as calculated by the response ratio analysis. Fig. S4. The percentage change in the relative abundance of genes associated with C fixation induced by N deposition, calculated as 100*(( mean value in N deposited samples/mean value in control samples) – 1). Mean values and standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010. The numbers in the figure represent the pathways of C fixation. (i) 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle, (ii) Bacterial microcompartments, (iii) Calvin cycle, and (iv) Reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle. Fig. S5. The percentage change in the relative abundance of genes associated with methane and phosphorus cycling genes induced by N deposition, calculated as 100*((mean value in N deposited samples/mean value in control samples) – 1). Mean values and standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010. Fig. S6. N deposition effects on amoA gene. The relative abundance of amoA is presented as the signal intensity difference between control and N deposited samples. Error bars represent standard errors. Blue bars represent genes derived from archaea (AOA), and pink bars represent genes derived from bacteria (AOB). Asterisks indicate significant differences. *, P < 0.050; **, P < 0.010.

Data Availability Statement

GeoChip data are available online (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number GSE107168. MiSeq data are available in the NCBI SRA database with the accession number SRP126539.