Abstract

A DNA molecule is highly electrically charged in solution. The electrical potential at the molecular surface is known to vary strongly with the local geometry of the double helix and plays a pivotal role in DNA–protein interactions. Further out from the molecular surface, the electrical field propagating into the surrounding electrolyte bears fingerprints of the three-dimensional arrangement of the charged atoms in the molecule. However, precise extraction of the structural information encoded in the electrostatic “far field” has remained experimentally challenging. Here, we report an optical microscopy-based approach that detects the field distribution surrounding a charged molecule in solution, revealing geometric features such as the radius and the average rise per basepair of the double helix with up to sub-Angstrom precision, comparable with traditional molecular structure determination techniques like X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance. Moreover, measurement of the helical radius furnishes an unprecedented view of both hydration and the arrangement of cations at the molecule–solvent interface. We demonstrate that a probe in the electrostatic far field delivers structural and chemical information on macromolecules, opening up a new dimension in the study of charged molecules and interfaces in solution.

Nucleic acids play a central role in biological function. Investigation of the structure of nucleic acids has had a long and compelling history and continues to have far-reaching impact in fields ranging from molecular biology, genetics and disease, to nanotechnology. A range of powerful techniques such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), atomic force microscopy (AFM), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), Forster resonance energy transfer, and optical trapping have generated an unprecedented structural view of DNA, covering all length scales from the atomic to the macroscopic polymer contour level.1−8 The structural properties and function of this biopolymer in solution are strongly governed not only by steric and mechanical aspects but also by electrostatic considerations, as it is among the most highly charged linear polymers known.9,10 Indeed, electrical mobility measurements provided an early demonstration of the link between nucleic acid electrostatics and double helix geometry and molecular topology.11 More recently, magnetic tweezers and SAXS have been used to infer molecular properties of nucleic acids via the measurement of an intra- or intermolecular interaction potential.12,13 Furthermore, anomalous SAXS and atomic emission spectroscopy (AES) have probed the properties of the counterion atmosphere enveloping nucleic acid molecules,14,15 while X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) has shed light on the interface between a charged nanoparticle and the surrounding electrolyte.16 To our knowledge, the ability to glean structural information on a diffusing macromolecule and its interface with the electrolyte through precise measurement of the electrical repulsion due to the molecule has not been demonstrated.

Experimental Approach

We optically visualize and measure the strength

of electrostatic

repulsions between a charged molecule and like-charged probe surfaces

in solution using wide-field fluorescence microscopy and the recently

developed escape time electrometry (ETe) approach.17 In contrast to scanning probe techniques where

a nanoscale entity is placed in near contact with a stationary object

of interest, our experiment involves a pair of flat, featureless probe

surfaces placed in the “far field” of a diffusing charged

molecular species in solution. We qualitatively define the electrostatic

“far field” as the region in the electrolyte at a distance

greater than a Debye length,  , from

the object. Here,

, from

the object. Here,  nm is a length

scale governing the decay

of electrostatic interactions in aqueous solution at temperature T = 298 K, where the salt concentration in solution, c ≈ 1–1.5 mM in this work, implies

nm is a length

scale governing the decay

of electrostatic interactions in aqueous solution at temperature T = 298 K, where the salt concentration in solution, c ≈ 1–1.5 mM in this work, implies  8 nm. ETe measures the

reduction in system free energy associated with transferring a charged

molecule from a gap between like-charged parallel plates into a nanostructured

“trap” region of very weak confinement where the molecule–plate

repulsion is negligible18 (Figure 1a,b). The system is at thermodynamic

equilibrium, and there are no externally applied fields. We create

an array of such electrostatic fluidic traps using periodic nanostructured

indentations in one surface of a parallel plate slit composed of silica

surfaces separated by a gap of typical height, 2h = 75 nm. We introduce nucleic acid molecules at a concentration

of 50–100 pM labeled with exactly two fluorescent dye molecules

of ATTO 532, suspended in 1 mM Tris buffer and ≈1.2 mM monovalent

salt solution, pH 9, into a system with multiple parallel lattices

of traps (Figure 1a).

Alkaline pH in the experiment ensures that the weakly acidic SiO2 walls of our nanoslit system are strongly charged.19 A low (mM) concentration of monovalent salt,

in turn, ensures that the electrostatic interactions between a charged

molecule and the walls of the slit are sufficiently strong and long-ranged,

yielding long-lived trap states of ≈50–200 ms duration.

Analytical characterization of the molecular species in the study

using, for example, circular dichroism spectroscopy verifies that

the solution conditions in our measurement conditions do not perturb

the molecules’ structural integrity (see Supporting Information Figure S2).

8 nm. ETe measures the

reduction in system free energy associated with transferring a charged

molecule from a gap between like-charged parallel plates into a nanostructured

“trap” region of very weak confinement where the molecule–plate

repulsion is negligible18 (Figure 1a,b). The system is at thermodynamic

equilibrium, and there are no externally applied fields. We create

an array of such electrostatic fluidic traps using periodic nanostructured

indentations in one surface of a parallel plate slit composed of silica

surfaces separated by a gap of typical height, 2h = 75 nm. We introduce nucleic acid molecules at a concentration

of 50–100 pM labeled with exactly two fluorescent dye molecules

of ATTO 532, suspended in 1 mM Tris buffer and ≈1.2 mM monovalent

salt solution, pH 9, into a system with multiple parallel lattices

of traps (Figure 1a).

Alkaline pH in the experiment ensures that the weakly acidic SiO2 walls of our nanoslit system are strongly charged.19 A low (mM) concentration of monovalent salt,

in turn, ensures that the electrostatic interactions between a charged

molecule and the walls of the slit are sufficiently strong and long-ranged,

yielding long-lived trap states of ≈50–200 ms duration.

Analytical characterization of the molecular species in the study

using, for example, circular dichroism spectroscopy verifies that

the solution conditions in our measurement conditions do not perturb

the molecules’ structural integrity (see Supporting Information Figure S2).

Figure 1.

High-precision ETe measurements on nucleic acid

fragments. (a) Schematic representation (not-to-scale) of fluorescently

labeled nucleic acid molecules confined in an array of electrostatic

fluidic traps and imaged using wide-field optical microscopy (top).

Maximum intensity projection of 500 fluorescence images of parallel

arrays of ≈700 traps imaged for 20 s (bottom). (b) Calculated

spatial distribution of minimum axial electrostatic free energy,  , in a representative trap (top). Labels

“1” and “2” denote locations of the molecule

outside and inside the potential well, respectively, and refer to

spatial locations in the trapping nanostructure depicted in the device

schematic in (a). A time course of optical images in a single trap

(bottom) displays the duration of a single recorded residence event

of duration, Δt. (c) Probability density distributions, P(Δt), of escape times, Δt, for N = 104 escape events

for measurements on double-stranded B-DNA (solid lines) and A-RNA

(dashed lines) in 1.23 mM LiCl for fragment length nb = 30 (red), 40 (blue), and 60 (green) basepairs fitted

to the expression

, in a representative trap (top). Labels

“1” and “2” denote locations of the molecule

outside and inside the potential well, respectively, and refer to

spatial locations in the trapping nanostructure depicted in the device

schematic in (a). A time course of optical images in a single trap

(bottom) displays the duration of a single recorded residence event

of duration, Δt. (c) Probability density distributions, P(Δt), of escape times, Δt, for N = 104 escape events

for measurements on double-stranded B-DNA (solid lines) and A-RNA

(dashed lines) in 1.23 mM LiCl for fragment length nb = 30 (red), 40 (blue), and 60 (green) basepairs fitted

to the expression  . In order to enable comparison across different

molecular species, P(Δt) data

series are rescaled such that the maximum value is 1. Average escape

times, tesc, and measured effective charge

values, qm, are as follows: tesc,30B = 52.2 ± 0.3 ms (qm,30B = −25.28 ± 0.07e), tesc,40B 93.9 ± 0.4 ms (

. In order to enable comparison across different

molecular species, P(Δt) data

series are rescaled such that the maximum value is 1. Average escape

times, tesc, and measured effective charge

values, qm, are as follows: tesc,30B = 52.2 ± 0.3 ms (qm,30B = −25.28 ± 0.07e), tesc,40B 93.9 ± 0.4 ms ( 30.46 ± 0.06e), and

30.46 ± 0.06e), and  242.5 ± 1.1 ms (

242.5 ± 1.1 ms ( 40.71 ± 0.07e) for

B-DNA and

40.71 ± 0.07e) for

B-DNA and  46.3 ± 0.2 ms (−23.86

±

0.04e),

46.3 ± 0.2 ms (−23.86

±

0.04e),  70.4 ± 0.8 ms (−28.35

±

0.13e), and

70.4 ± 0.8 ms (−28.35

±

0.13e), and  192.5 ± 0.6 ms (−37.26

±

0.04e) for A-RNA. B-DNA systematically displays 10–20%

longer escape times and higher magnitudes of effective charge than

A-RNA. Space filling structures of B-DNA and A-RNA reproduced with

permission from ref (3) (right).

192.5 ± 0.6 ms (−37.26

±

0.04e) for A-RNA. B-DNA systematically displays 10–20%

longer escape times and higher magnitudes of effective charge than

A-RNA. Space filling structures of B-DNA and A-RNA reproduced with

permission from ref (3) (right).

Imaging the escape dynamics of

trapped single molecules permits

us to identify individual molecular residence events of duration Δt in each trap. Photobleaching of the fluorescent dyes and

any potential impact thereof on the measurement have been carefully

explored in previous work.17 Because molecular

residence times in the trap are much shorter than dye photobleaching

times, we expect dye photophysics and photochemistry not to influence

the accuracy of our measured escape times. Overdamped escape of an

object from a potential well can be treated as a Poisson process with

residence times that are exponentially distributed.20 Fits of the measured probability density function of residence

times, P(Δt), to an exponential

function of the form  permit us to extract precise measurements

of the molecular species’ average time to escape,

permit us to extract precise measurements

of the molecular species’ average time to escape,  (Figure 1b,c). The average

escape time, in turn, is expected

to depend exponentially on well depth, according to the relation

(Figure 1b,c). The average

escape time, in turn, is expected

to depend exponentially on well depth, according to the relation  ,20 permitting

us to relate measured

,20 permitting

us to relate measured  values

to the depth of the trap, W, in the regime of W > 4kBT. In practice, we use Brownian dynamics

(BD) simulations of the escape process in order to accurately convert

measurements of

values

to the depth of the trap, W, in the regime of W > 4kBT. In practice, we use Brownian dynamics

(BD) simulations of the escape process in order to accurately convert

measurements of  to

the well depth, W,

as described previously17,21,22 (Supporting Information Section S2).

to

the well depth, W,

as described previously17,21,22 (Supporting Information Section S2).

In our BD simulations, we treat molecules as effective spheres

of a radius equal to the measured hydrodynamic radius of the molecule.

The hydrodynamic radius, rH, of each molecular

species was measured using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy as

described in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Methods). The use of an effective hydrodynamic radius,

which ignores the anisotropic diffusive behavior of non-spherical

objects, is valid when the translational diffusive length scale of

interest, ls, is much larger than the

length of the molecule, l, or in other words, when

the ratio of rotational and translational diffusive timescales  . For a rigid cylinder of length l, this ratio is approximately l2/ls2 (see ref (23)). The relevant length scale for translational diffusion, ls, in an ETe measurement corresponds

to the radius of a nanostructured pocket which is typically 250–300

nm. Given the contour length of a 60 bp B-DNA (l ≈

20 nm), which is the longest fragment considered here, we have l2/ls ≈ 0.01 ≪ 1, which ensures

that the translational diffusion of an anisometric object may be treated

as equivalent to that of an effective sphere for large displacements.

It is worth noting that we ignore inertial effects in our BD simulations

on the grounds that the momentum relaxation time of the molecule is

very small.24 Although inertial BD simulations

of large supercoiled DNA plasmids (∼1000 bp) have shown that

mass can have some effects on conformation transition rates in equilibrium,

they do also demonstrate that the translational diffusion coefficient

of these molecules is accurately captured by conventional BD simulations.24,25 Thus, for short nucleic acid fragments, which are expected to behave

like rigid rods, BD simulations in the overdamped regime are expected

to provide an accurate description of our escape time problem.

. For a rigid cylinder of length l, this ratio is approximately l2/ls2 (see ref (23)). The relevant length scale for translational diffusion, ls, in an ETe measurement corresponds

to the radius of a nanostructured pocket which is typically 250–300

nm. Given the contour length of a 60 bp B-DNA (l ≈

20 nm), which is the longest fragment considered here, we have l2/ls ≈ 0.01 ≪ 1, which ensures

that the translational diffusion of an anisometric object may be treated

as equivalent to that of an effective sphere for large displacements.

It is worth noting that we ignore inertial effects in our BD simulations

on the grounds that the momentum relaxation time of the molecule is

very small.24 Although inertial BD simulations

of large supercoiled DNA plasmids (∼1000 bp) have shown that

mass can have some effects on conformation transition rates in equilibrium,

they do also demonstrate that the translational diffusion coefficient

of these molecules is accurately captured by conventional BD simulations.24,25 Thus, for short nucleic acid fragments, which are expected to behave

like rigid rods, BD simulations in the overdamped regime are expected

to provide an accurate description of our escape time problem.

The highly non-linear dependence of the measurand (escape time,  ) on

the measurable (well depth, W) facilitates precise

interaction energy measurements.

Observation of a large number of escape events, N ≈ 104, reduces the fractional statistical uncertainty

in the determination of W to about 0.1%.22 Importantly, the dominant contribution to the

trap depth, W, is the electrostatic free energy of

interaction,

) on

the measurable (well depth, W) facilitates precise

interaction energy measurements.

Observation of a large number of escape events, N ≈ 104, reduces the fractional statistical uncertainty

in the determination of W to about 0.1%.22 Importantly, the dominant contribution to the

trap depth, W, is the electrostatic free energy of

interaction,  , which

has robust theoretical underpinnings

in the Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) framework for solution phase

electrostatics as discussed further later.26−28 Correction

of a contribution from axial spatial fluctuations to the total free

energy, W, permits us to determine

, which

has robust theoretical underpinnings

in the Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) framework for solution phase

electrostatics as discussed further later.26−28 Correction

of a contribution from axial spatial fluctuations to the total free

energy, W, permits us to determine  with

high precision, as described further

in Supporting Information, Section S2.

We have previously shown that

with

high precision, as described further

in Supporting Information, Section S2.

We have previously shown that  may

be regarded in terms of the product

of the effective charge of the molecule in solution,

may

be regarded in terms of the product

of the effective charge of the molecule in solution,  , and

the electrical potential, ϕm, at the midplane of

the slit, such that

, and

the electrical potential, ϕm, at the midplane of

the slit, such that  =

=  .29,30 If ϕm is accurately known,

the measurable in our experiment is the effective

charge,

.29,30 If ϕm is accurately known,

the measurable in our experiment is the effective

charge,  , of

the molecular species under the experimental

conditions. Note that our values of

, of

the molecular species under the experimental

conditions. Note that our values of  for

charged spheres and cylinders are comparable

to those encountered in other charge renormalization theories.30−32 Furthermore, our interaction-energy-based definition of

for

charged spheres and cylinders are comparable

to those encountered in other charge renormalization theories.30−32 Furthermore, our interaction-energy-based definition of  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  =

=  ) is identical to that in Kjellander’s

dressed ion theory.33−36

) is identical to that in Kjellander’s

dressed ion theory.33−36

The principle behind the present study may be summarized as

follows:

Accurate measurements of the electrostatic free energy,  permit us to measure the effective

charge,

permit us to measure the effective

charge,  , of

three different lengths of a nucleic

acid species (e.g., A- or B-form helix in this work). Theoretically

expected effective charge values may also be calculated using the

PB theoretical framework for each length of the fragment, as described

previously (see Supporting Information Section

S7).30 As described further below, calculations

show that

, of

three different lengths of a nucleic

acid species (e.g., A- or B-form helix in this work). Theoretically

expected effective charge values may also be calculated using the

PB theoretical framework for each length of the fragment, as described

previously (see Supporting Information Section

S7).30 As described further below, calculations

show that  depends

strongly on geometrical dimensions

of the molecular species of interest, for example, the rise per basepair, b, and helical radius, r. The precise functional

form of this dependence is itself a function of the length of each

fragment, as shown in Figures 3a and S4a. Thus,

we have three independent theoretical relationships relating effective

charge with molecular geometry for the fragment lengths under consideration.

Since the effective charge of the molecular conformation under study

(e.g., either the A-form or the B-form helix) may be described by

a common pair of underlying geometric parameters

(e.g., rise per basepair, b, and helical radius, r), a comparison of the measured effective charge values

with the theoretically expected values for the three lengths of the

double helix permits us to extract estimates of the two geometric

properties of interest (described in detail in Supporting Information, Section S4). The third parameter we

extract from the analysis characterizes the measurement device. We

find that measurements of the helical radius in electrolytes containing

cations of different radii further permit us to make inferences on

the structure of the molecular interface with the electrolyte.

depends

strongly on geometrical dimensions

of the molecular species of interest, for example, the rise per basepair, b, and helical radius, r. The precise functional

form of this dependence is itself a function of the length of each

fragment, as shown in Figures 3a and S4a. Thus,

we have three independent theoretical relationships relating effective

charge with molecular geometry for the fragment lengths under consideration.

Since the effective charge of the molecular conformation under study

(e.g., either the A-form or the B-form helix) may be described by

a common pair of underlying geometric parameters

(e.g., rise per basepair, b, and helical radius, r), a comparison of the measured effective charge values

with the theoretically expected values for the three lengths of the

double helix permits us to extract estimates of the two geometric

properties of interest (described in detail in Supporting Information, Section S4). The third parameter we

extract from the analysis characterizes the measurement device. We

find that measurements of the helical radius in electrolytes containing

cations of different radii further permit us to make inferences on

the structure of the molecular interface with the electrolyte.

Figure 3.

Measuring the helical rise per basepair and radius of

the double

helix. (a) Principle behind the measurement of the helical rise per

basepair, b, and radius, r, of the

double helix, for an ideal experiment, free of systematic measurement

uncertainty (i.e., fM = 1). Schematic

representations of three lengths of a double-stranded nucleic acid

species surrounded by a cloud of screening counterions (left). A measured

value  for each molecular species of length n bp, in conjunction

with the corresponding calculated 2D

function (colored surface) for the effective charge,

for each molecular species of length n bp, in conjunction

with the corresponding calculated 2D

function (colored surface) for the effective charge,  , generates a curve of possible solutions

in b and r. Intersection of three

such curves for n = 30, 40, and 60 bp yields a probability-weighted

manifold of solutions from which measured values, bm and rm, for the rise and

radius, respectively, of each helix form can be obtained. (b) Measured b–r probability manifolds for B-DNA

(top) and A-RNA (bottom) for an experiment performed in 1.2 mM CsCl.

Since fM ≠ 1 in experiments, measured b–r manifolds are broader than those

in the ideal case depicted in (a) yielding

, generates a curve of possible solutions

in b and r. Intersection of three

such curves for n = 30, 40, and 60 bp yields a probability-weighted

manifold of solutions from which measured values, bm and rm, for the rise and

radius, respectively, of each helix form can be obtained. (b) Measured b–r probability manifolds for B-DNA

(top) and A-RNA (bottom) for an experiment performed in 1.2 mM CsCl.

Since fM ≠ 1 in experiments, measured b–r manifolds are broader than those

in the ideal case depicted in (a) yielding  3.2 Å and

3.2 Å and  10.4 Å and

10.4 Å and  2.6 Å and

2.6 Å and  12.5 Å for B-DNA and A-RNA, respectively.

12.5 Å for B-DNA and A-RNA, respectively.

For a highly charged molecule in solution, it has

been shown that  , where η is a molecular

geometry-dependent

charge renormalization factor.30−32,37,38

, where η is a molecular

geometry-dependent

charge renormalization factor.30−32,37,38 denotes

the net electrical charge in the

molecular structure and stems from the sum of charge carried by the

ionized structural groups and bound ions from the electrolyte. A highly

acidic molecule like DNA, n basepairs in length and

carrying a chemical modification at both 5′-end phosphates,

has a structural charge

denotes

the net electrical charge in the

molecular structure and stems from the sum of charge carried by the

ionized structural groups and bound ions from the electrolyte. A highly

acidic molecule like DNA, n basepairs in length and

carrying a chemical modification at both 5′-end phosphates,

has a structural charge  at pH 7 and higher (see Supporting Information, Section S3.2). Here, e is the elementary charge

and

at pH 7 and higher (see Supporting Information, Section S3.2). Here, e is the elementary charge

and  is the amount

of charge due to the backbone

phosphate groups on the molecule which are all fully ionized in our

experiments. However, if a number of positively charged counterions,

δ, associate with the molecule, for example, via energetic interactions

beyond the purely Coulombic that are already accounted for within

the PB model, then

is the amount

of charge due to the backbone

phosphate groups on the molecule which are all fully ionized in our

experiments. However, if a number of positively charged counterions,

δ, associate with the molecule, for example, via energetic interactions

beyond the purely Coulombic that are already accounted for within

the PB model, then  , where

, where  is an inverse ion affinity parameter which

tends to zero as

is an inverse ion affinity parameter which

tends to zero as  .

.

To a first approximation, a periodic

linear charged structure such

as a short fragment of a double-stranded nucleic acid may be viewed

as a smooth, charged cylinder of finite length.39,40 Here, η depends on the charge density of the polyelectrolyte

and therefore on the axial base spacing, b, and the

radius of the polyelectrolyte backbone, r. Considering

a short stretch of a nucleic acid whose contour length, l = nb, is of the order of the Debye length, η

further depends on l.17,41,42 Upon approximating a short stretch of DNA (≤60

bp) by a rigid cylinder of radius r and length l, we thus have  which can be calculated for a range of b and r values using the PB framework (Figures 2 and 3).29,30 Finally, for a given molecular

geometry and structural charge, η is essentially independent

of ion affinity for

which can be calculated for a range of b and r values using the PB framework (Figures 2 and 3).29,30 Finally, for a given molecular

geometry and structural charge, η is essentially independent

of ion affinity for  0.7. Although η does exhibit

some

dependence on the salt concentration, c, this variation

is negligible over the small range in experimental uncertainty in c in a given measurement.30,31

0.7. Although η does exhibit

some

dependence on the salt concentration, c, this variation

is negligible over the small range in experimental uncertainty in c in a given measurement.30,31

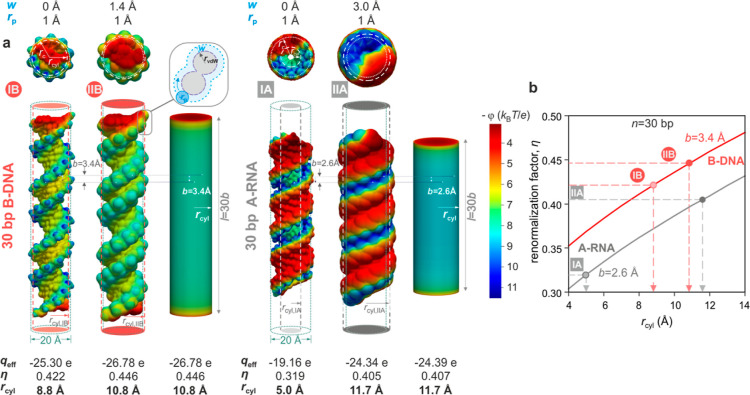

Figure 2.

Modeling the

double helix as a smooth charged cylinder of finite

length. (a) Distributions of surface electrostatic potential, ϕ,

for two molecular models of a 30 bp fragment of B-DNA (IB and IIB—left)

and A-RNA (IA and IIA—right) generated based on atomic coordinates

with rolling probe radius (rp = 1 Å)

and solvent accessible surface (w) parameter values

as listed and pictured (inset) alongside axial projections of the

molecular models (top panel). Surface potential distributions for

corresponding smooth charged cylinders equivalent to models IIB and

IIA carrying a total charge  60e with radii,

60e with radii,  10.8 Å and

10.8 Å and  11.7 Å, respectively, and length 30b Å in each case. The radius of the equivalent cylinder,

11.7 Å, respectively, and length 30b Å in each case. The radius of the equivalent cylinder,  (dashed

lines), may be compared with a

nominal double-helical radius rc = 10

Å (dotted lines). (b) Calculated trends for the renormalization

factor,

(dashed

lines), may be compared with a

nominal double-helical radius rc = 10

Å (dotted lines). (b) Calculated trends for the renormalization

factor,  , for cylinders of radius

, for cylinders of radius  and length 30b Å,

with nominal values of b = 3.4 Å for B-DNA (red

line) and 2.6 Å for A-RNA (gray line). η values for the

four molecular models can be related to those for smooth cylinders

and correspond to

and length 30b Å,

with nominal values of b = 3.4 Å for B-DNA (red

line) and 2.6 Å for A-RNA (gray line). η values for the

four molecular models can be related to those for smooth cylinders

and correspond to  8.8 Å(effective

vdW surface),

8.8 Å(effective

vdW surface),  10.8 Å (effective SAS),

10.8 Å (effective SAS),  5 Å (vdWS),

and

5 Å (vdWS),

and  11.7 Å (SAS), two of which are depicted

in (a). Panels are reproduced from ref (48), with the permission of AIP Publishing.

11.7 Å (SAS), two of which are depicted

in (a). Panels are reproduced from ref (48), with the permission of AIP Publishing.

In view

of the grooved molecular surface of double-stranded nucleic

acids and the helicoid distribution of charge on the molecular backbone,

we first test the quality of the smooth cylinder electrostatic model

for DNA in the context of our experiment (Figure 2). We calculate  and

therefore determine

and

therefore determine  values

for molecular models of the full

3D structure of 30 bp B-DNA and A-RNA molecules constructed using

the 3DNA platform (Supporting Information Section S7).43 We then determine

values

for molecular models of the full

3D structure of 30 bp B-DNA and A-RNA molecules constructed using

the 3DNA platform (Supporting Information Section S7).43 We then determine  values

for smooth cylinders of variable

radii, r, and the same axial rise per basepair, b, as the molecular helices. Cylinders of radius

values

for smooth cylinders of variable

radii, r, and the same axial rise per basepair, b, as the molecular helices. Cylinders of radius  whose

whose  values

are identical to those of the molecular

helices within computational error (estimated at <0.1%) are termed

equivalent cylinders. Physically, this means that the computed electrostatic

free energy difference between the "free" and "trapped"

states (states1

and 2 in Fig. 1b respectively)of

the molecular helix,

values

are identical to those of the molecular

helices within computational error (estimated at <0.1%) are termed

equivalent cylinders. Physically, this means that the computed electrostatic

free energy difference between the "free" and "trapped"

states (states1

and 2 in Fig. 1b respectively)of

the molecular helix,  , is indistinguishable from that due to

a smooth cylinder of radius

, is indistinguishable from that due to

a smooth cylinder of radius  . Importantly,

a domain decomposition of

the free energy in the system demonstrates that the electrostatic

well depth of the trap,

. Importantly,

a domain decomposition of

the free energy in the system demonstrates that the electrostatic

well depth of the trap,  , stems in nearly equal proportions from

the “near field” (the region within about 2 nm) of both

the molecule and the slit surfaces48. Note

that high-resolution structural studies have shown that the double

helix can have local structural variability, for example, sequence-dependent

and thermally induced variation of the rise per basepair along the

molecular contour, which is not captured in the uniformly charged

cylinder model.44−47 Our approach measures an averaged interaction response from the

molecule. Whereas thermal variations are expected to average out in

the measurement, local sequence-dependent variations will be interpreted

in terms of an average rise per basepair parameter

characterizing the molecule. Therefore, for the current work, we assume

that a coarse-grained model that treats the double helix as a uniformly

charged cylinder provides a sufficient description of the measurement.

Although mapping of the molecular problem on to that of a uniform

cylinder can be highly informative, future work could directly compare

electrometry measurements with expectations for molecular structural

models.

, stems in nearly equal proportions from

the “near field” (the region within about 2 nm) of both

the molecule and the slit surfaces48. Note

that high-resolution structural studies have shown that the double

helix can have local structural variability, for example, sequence-dependent

and thermally induced variation of the rise per basepair along the

molecular contour, which is not captured in the uniformly charged

cylinder model.44−47 Our approach measures an averaged interaction response from the

molecule. Whereas thermal variations are expected to average out in

the measurement, local sequence-dependent variations will be interpreted

in terms of an average rise per basepair parameter

characterizing the molecule. Therefore, for the current work, we assume

that a coarse-grained model that treats the double helix as a uniformly

charged cylinder provides a sufficient description of the measurement.

Although mapping of the molecular problem on to that of a uniform

cylinder can be highly informative, future work could directly compare

electrometry measurements with expectations for molecular structural

models.

We considered two molecular models each for B-DNA and

A-RNA, with

all molecular surfaces generated using rolling probe radii, rp = 1 Å. Models-IA and -IB were generated

using reference van der Waals (vdW) values for all atoms, while models-II

A and -IIB entail atomic radii that are all w = 3

Å and w = 1.4 Å larger than the vdW values,

respectively (Figure 2a). While model-I is expected to capture the vdW surface (vdWS) of

the molecule, a larger atomic radius in model-II is expected to mimic

a “solvent accessible surface” (SAS) which defines the

distance of closest approach of the center of a water molecule to

the macromolecular structure. For B-DNA, we find that models-I and

-II yield equivalent electrostatic cylinder radii,  9 Å

and

9 Å

and  11 Å, respectively,

which are in remarkable

agreement with the nominal outer helical radius, rc ≈ 10 Å, inferred from molecular crystal

structures (Figure 2b).28 Interestingly, for A-RNA, the

11 Å, respectively,

which are in remarkable

agreement with the nominal outer helical radius, rc ≈ 10 Å, inferred from molecular crystal

structures (Figure 2b).28 Interestingly, for A-RNA, the  values

for the two structures considered

are rather different:

values

for the two structures considered

are rather different:  5 Å

and

5 Å

and  12 Å, suggesting that an experimental

measurement with sufficient accuracy may be able to distinguish between

the two models, shedding light on molecular interfacial structural

detail in an electrolyte (Supporting Information Section S7). The modeling procedure has been described in detail

previously48 and is summarized in Supporting Information Section S7.

12 Å, suggesting that an experimental

measurement with sufficient accuracy may be able to distinguish between

the two models, shedding light on molecular interfacial structural

detail in an electrolyte (Supporting Information Section S7). The modeling procedure has been described in detail

previously48 and is summarized in Supporting Information Section S7.

Precise

measurements (uncertainty<1%) of  on

three nucleic acid fragments of different

lengths may be compared with calculated

on

three nucleic acid fragments of different

lengths may be compared with calculated  values

for charged cylinders in order to

extract measures of three unknown quantities of interest (Figure 3a). Two of these

three unknowns describe geometric properties of the underlying molecular

structure, namely, the radius of the helix, r, and

the axial helical rise per basepair, b. The third

unknown relates to experimental measurement conditions and the associated

uncertainty. Experiments generally contain parameters that need to

be well controlled, or accounted for, in order to foster accurate

measurements. We account for uncertainties in various experimental

quantities through the use of two correction terms: one is a multiplicative

factor, fM, and the other is an additive

quantity, fA, such that the measured effective

charge for each fragment of size n bases is given

by

values

for charged cylinders in order to

extract measures of three unknown quantities of interest (Figure 3a). Two of these

three unknowns describe geometric properties of the underlying molecular

structure, namely, the radius of the helix, r, and

the axial helical rise per basepair, b. The third

unknown relates to experimental measurement conditions and the associated

uncertainty. Experiments generally contain parameters that need to

be well controlled, or accounted for, in order to foster accurate

measurements. We account for uncertainties in various experimental

quantities through the use of two correction terms: one is a multiplicative

factor, fM, and the other is an additive

quantity, fA, such that the measured effective

charge for each fragment of size n bases is given

by  . The correction factor, fM = fionRfϕ, accounts

for effects that influence the measured effective charge in a multiplicative

fashion and is, in turn, composed of two terms. fϕ reflects a property of the measurement apparatus

and involves the overall uncertainty in the midplane electrical potential,

ϕm, in the slit. ϕm directly relates

to the effective surface potential of the silica surfaces, ϕs, via the relation ϕm = 2ϕs exp(−

. The correction factor, fM = fionRfϕ, accounts

for effects that influence the measured effective charge in a multiplicative

fashion and is, in turn, composed of two terms. fϕ reflects a property of the measurement apparatus

and involves the overall uncertainty in the midplane electrical potential,

ϕm, in the slit. ϕm directly relates

to the effective surface potential of the silica surfaces, ϕs, via the relation ϕm = 2ϕs exp(− h), and we use

a nominal

value of ϕs = −2.8

h), and we use

a nominal

value of ϕs = −2.8 for our experimental conditions as noted

in previous work.21 Examples of factors

that contribute to variations in fϕ include the finite accuracy of the order of he ≈ 1 nm in the height of the slit, the particular value

of the surface charge density on the confining walls, the salt concentration,

and possible ionic species effects on ϕs. fion, in turn, represents a relative "inverse affinity" of

cations for

the nucleic acid molecule, measured with respect to Na+ ions, such that fNaR = 1. Finally, fA is an additive term, the main contribution to which is

for our experimental conditions as noted

in previous work.21 Examples of factors

that contribute to variations in fϕ include the finite accuracy of the order of he ≈ 1 nm in the height of the slit, the particular value

of the surface charge density on the confining walls, the salt concentration,

and possible ionic species effects on ϕs. fion, in turn, represents a relative "inverse affinity" of

cations for

the nucleic acid molecule, measured with respect to Na+ ions, such that fNaR = 1. Finally, fA is an additive term, the main contribution to which is  0.5e, the effective charge

of the fluorescent label covalently coupled to both 5′-phosphates

of the double helix, which is determined by measurement (see Supporting Information, Section S3).

0.5e, the effective charge

of the fluorescent label covalently coupled to both 5′-phosphates

of the double helix, which is determined by measurement (see Supporting Information, Section S3).

We

constructed 30, 60, and 40 bp fragments of dsDNA and dsRNA and

measured the effective charge for each molecular species. We then

compared the measured effective charge values, qm, with the corresponding calculated values,  , for

cylinders with linear charge spacing

corresponding to rise per basepair values, b, ranging

from 2 to 5 Å and the radius, r, in the range

of 6–30 Å. In principle, simultaneously solving the three

known relationships for

, for

cylinders with linear charge spacing

corresponding to rise per basepair values, b, ranging

from 2 to 5 Å and the radius, r, in the range

of 6–30 Å. In principle, simultaneously solving the three

known relationships for  with

with  for the three fragments should yield values

for the unknowns b and r when fM = 1 (Figure 3a). However, in general, fM ≠ 1, and the measurement data, which are of the form

for the three fragments should yield values

for the unknowns b and r when fM = 1 (Figure 3a). However, in general, fM ≠ 1, and the measurement data, which are of the form  , are not single-valued but rather carry

Gaussian-distributed uncertainties of width

, are not single-valued but rather carry

Gaussian-distributed uncertainties of width  about the mean value, qm. Thus, we have three functions of the form

about the mean value, qm. Thus, we have three functions of the form  Pairwise division of these three

equations

eliminates fM and results in two functions

that may be numerically solved to yield a probability-weighted manifold

of solutions in b and r (Figure 3b). We determine

the most probable measured values bm and rm using an algorithm developed based on simulated

input data. fM is then determined self-consistently

by substitution into one of the three equations for

Pairwise division of these three

equations

eliminates fM and results in two functions

that may be numerically solved to yield a probability-weighted manifold

of solutions in b and r (Figure 3b). We determine

the most probable measured values bm and rm using an algorithm developed based on simulated

input data. fM is then determined self-consistently

by substitution into one of the three equations for  (Supporting Information Figure S4 and Section

S4).

(Supporting Information Figure S4 and Section

S4).

Results

We measured the radius, r, and

axial rise per

basepair, b, for dsDNA and dsRNA in solution containing

alkali metal chlorides LiCl, NaCl, RbCl, and CsCl. Although the bare

cationic radius decreases in the order Cs → Li, in an electrolyte,

hydrated ionic radii increase with decreasing ionic radius due to

favorable interactions between the ionic core and the surrounding

polarizable water molecules (Figure 4). We found that our measured rise per basepair values

for B-DNA and A-RNA are essentially insensitive to the nature of the

cation in solution, and we obtained rise values averaged over all

measurements of  3.1 ± 0.1 Å and

3.1 ± 0.1 Å and  2.5 ± 0.1 Å for B-form and A-form

helices, respectively (Figure 4a, top). These measurements compare well with values from

crystallography and NMR.2,3,5,45,49

2.5 ± 0.1 Å for B-form and A-form

helices, respectively (Figure 4a, top). These measurements compare well with values from

crystallography and NMR.2,3,5,45,49

Figure 4.

Inferring

the structure of the molecule–electrolyte interface.

(a) Measured helical rise per basepair, bm (top), and radius, rm (bottom), as a

function of the hydrated cation radius, aH. Error bars denote s.e.m. Rise per basepair values show no significant

variation with aH and yield average values

of  3.1 ± 0.1 Å and

3.1 ± 0.1 Å and  2.5 ± 0.1 Å.

Helical radius data

were fit with a function of the form

2.5 ± 0.1 Å.

Helical radius data

were fit with a function of the form  , yielding

, yielding  10.5 ± 0.6 Å

and

10.5 ± 0.6 Å

and  11.8 ± 0.6 Å. The slope, k = 0.8 ±

0.2, is a shared fit parameter in both relationships.

(b) Cylinder of radius

11.8 ± 0.6 Å. The slope, k = 0.8 ±

0.2, is a shared fit parameter in both relationships.

(b) Cylinder of radius  10.5

10.5  (blue

dashed cylinder) depicting that the

effective cylinder in model-IIB of B-DNA is superimposed for comparison

on the vdW molecular surface in model-IB (gray dashed cylinder). k = 0.8 ± 0.2 suggests that the distance of the closest

approach of screening cations to the molecular surface is directly

related to the radius of the hydrated cation species, aH. The resulting effective “ion accessible surface”

(IAS) is the distance from the molecular axis beyond which the point-ion

description of the electrolyte may be invoked (red, green, and blue

dotted lines). The molecular structure may carry bound ions (yellow

spheres) whose charge is included in

(blue

dashed cylinder) depicting that the

effective cylinder in model-IIB of B-DNA is superimposed for comparison

on the vdW molecular surface in model-IB (gray dashed cylinder). k = 0.8 ± 0.2 suggests that the distance of the closest

approach of screening cations to the molecular surface is directly

related to the radius of the hydrated cation species, aH. The resulting effective “ion accessible surface”

(IAS) is the distance from the molecular axis beyond which the point-ion

description of the electrolyte may be invoked (red, green, and blue

dotted lines). The molecular structure may carry bound ions (yellow

spheres) whose charge is included in  . (c)

For A-RNA, model-IIA which includes

a SAS of thickness w = 3 Å meets the condition

. (c)

For A-RNA, model-IIA which includes

a SAS of thickness w = 3 Å meets the condition  12 Å

(blue dashed cylinder). (d) Extrapolating

the inferred structure of the molecule–electrolyte interface

in (b) to a view of a macroscopic interface in solution where w < 3 Å.

12 Å

(blue dashed cylinder). (d) Extrapolating

the inferred structure of the molecule–electrolyte interface

in (b) to a view of a macroscopic interface in solution where w < 3 Å.

In contrast to the response of the helical rise to the cationic

species in solution, we found that the inferred helical radii tended

to increase in the order Cs → Li (Figure 4a, bottom). We further systematically found

that  with an average

difference in helical radii

between A and B forms of about 1–2 Å. Using values for

hydrated ionic radii, aH, determined from

ionic mobilities and slip hydrodynamic boundary conditions, and plotting

measured helical radii, rm, against aH, revealed a linear relationship between the

two quantities.50 Extrapolating the measured rm values to aH =

0 yielded values for r0 that may be thought

to represent the measured radii of equivalent cylinders in a hypothetical

electrolyte containing point ions (Figure 4a). We obtained

with an average

difference in helical radii

between A and B forms of about 1–2 Å. Using values for

hydrated ionic radii, aH, determined from

ionic mobilities and slip hydrodynamic boundary conditions, and plotting

measured helical radii, rm, against aH, revealed a linear relationship between the

two quantities.50 Extrapolating the measured rm values to aH =

0 yielded values for r0 that may be thought

to represent the measured radii of equivalent cylinders in a hypothetical

electrolyte containing point ions (Figure 4a). We obtained  10.5 ± 0.6

Å and

10.5 ± 0.6

Å and  11.8 ± 0.6

Å for B-DNA and A-RNA,

respectively (Figure 4a). Atomic models of B-DNA and A-RNA display axial radii of gyration

of ≈6.7 and ≈7.8 Å and have helical radii of ≈8

and ≈9.5 Å based on the main backbone carbon atoms, respectively

(Supporting Information Figure S10a). Thus,

in addition to the average axial charge separation, our measurement

is sensitive to the radial arrangement of atoms in the double helix.

The latter appears to contribute to an effective electrical molecular

surface topography, the geometry of which can be sensed even by a

probe in the electrostatic far field, according to our measurements

(Figure 2a and Supporting Information Figure S10b).10Figure S9 further

examines the influence of various literature estimates of hydrated

cationic radii on the inferred trends in rm.

11.8 ± 0.6

Å for B-DNA and A-RNA,

respectively (Figure 4a). Atomic models of B-DNA and A-RNA display axial radii of gyration

of ≈6.7 and ≈7.8 Å and have helical radii of ≈8

and ≈9.5 Å based on the main backbone carbon atoms, respectively

(Supporting Information Figure S10a). Thus,

in addition to the average axial charge separation, our measurement

is sensitive to the radial arrangement of atoms in the double helix.

The latter appears to contribute to an effective electrical molecular

surface topography, the geometry of which can be sensed even by a

probe in the electrostatic far field, according to our measurements

(Figure 2a and Supporting Information Figure S10b).10Figure S9 further

examines the influence of various literature estimates of hydrated

cationic radii on the inferred trends in rm.

Our measured r0 values may be

thought

to reflect a hypothetical experimental scenario involving point ions

in solution (Supporting Information Section

S7.5). We therefore expect these values to be amenable to direct comparison

with the quantity  computed

for the molecular models. We find

that

computed

for the molecular models. We find

that  10.5 ± 0.6

Å is comparable to

10.5 ± 0.6

Å is comparable to  10.8 Å obtained for model-II of B-DNA

that incorporates a SAS region of width w = 1.4 Å

(Figures 4b and 2a). For A-RNA, we obtain agreement between the measured

value of

10.8 Å obtained for model-II of B-DNA

that incorporates a SAS region of width w = 1.4 Å

(Figures 4b and 2a). For A-RNA, we obtain agreement between the measured

value of  11.8 ± 0.6

Å and a molecular

model constructed using w = 3 Å, yielding

11.8 ± 0.6

Å and a molecular

model constructed using w = 3 Å, yielding  11.7 Å, as reflected in model II-A.

Taken together, the measurements and the molecular electrostatic models

for both B-DNA and A-RNA would point to the presence of a hydration

layer of thickness 1 ≲ w ≲ 3 Å.

This is in general agreement with the value of 1.4 ± 0.6 Å

reported in a study using XPS of the Stern layer at the silica–water

interface.16,51 Furthermore, the large disparity

between the measured rm value for A-RNA

and the

11.7 Å, as reflected in model II-A.

Taken together, the measurements and the molecular electrostatic models

for both B-DNA and A-RNA would point to the presence of a hydration

layer of thickness 1 ≲ w ≲ 3 Å.

This is in general agreement with the value of 1.4 ± 0.6 Å

reported in a study using XPS of the Stern layer at the silica–water

interface.16,51 Furthermore, the large disparity

between the measured rm value for A-RNA

and the  value

calculated for model-IA would appear

to strongly preclude a molecular electrostatic model that neglects

hydration at the molecular interface. A combination of the “hollow

spine” along the A-RNA molecular axis, the deep and narrow

major groove, and the closer packing of charged atoms in general would

appear to render a measurement of the electrostatic free energy of

A-RNA a more sensitive probe of interfacial structural detail and

the finite size of ions in solution compared to B-DNA.52,53 Finally, our inferred slope for the rm versus aH relationship, k = 0.8 ± 0.2 ≈ 1, suggests that the radius of the effective

cylindrical molecular surface contour in solution is enlarged by an

amount that correlates with the radius of the hydrated cation (Figure 4c). Thus, in our

picture, the thickness of the “Stern layer” at the molecular

interface has a strong contribution from the size of the counterion

in the electrolyte (Figure 4c,d).

value

calculated for model-IA would appear

to strongly preclude a molecular electrostatic model that neglects

hydration at the molecular interface. A combination of the “hollow

spine” along the A-RNA molecular axis, the deep and narrow

major groove, and the closer packing of charged atoms in general would

appear to render a measurement of the electrostatic free energy of

A-RNA a more sensitive probe of interfacial structural detail and

the finite size of ions in solution compared to B-DNA.52,53 Finally, our inferred slope for the rm versus aH relationship, k = 0.8 ± 0.2 ≈ 1, suggests that the radius of the effective

cylindrical molecular surface contour in solution is enlarged by an

amount that correlates with the radius of the hydrated cation (Figure 4c). Thus, in our

picture, the thickness of the “Stern layer” at the molecular

interface has a strong contribution from the size of the counterion

in the electrolyte (Figure 4c,d).

Importantly, we find that a PB model of the electrostatics in conjunction with a geometric modification of the object—a slight inflation of the cylindrical radius in this case—is sufficient to model measured free energies in an experimental system with finite-sized ions.42 A comparison between all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and a PB model of nucleic acids reveals that the latter is capable of capturing many features evident in MD simulations, for example, integrated spatial free energy density profiles which are central to our work. However, it has also been pointed out that detailed agreement between a PB model and MD simulations, for example, at the level of spatial ionic densities in the major groove of A-RNA, will likely require a suitably modified PB theory.53,54 In future, a modified PB model for a charged cylinder of a fixed radius, which self-consistently accounts for hydration and finite ion-size effects, is likely to provide a common underlying framework to explain the results for both A- and B-form helices.55 Such a model will likely furnish more refined estimates of the interfacial parameters of interest, for example, w, k, and aH.

To conclude the study, we focus on fM, a parameter describing the experimental apparatus, determined

in

the measurement alongside bm and rm. Like rm, we found

that fM displayed a systematic dependence

on the cationic species in solution. For measurements that hold fixed

all other experimental parameters, such as the slit height and salt

concentration, any cation species-dependent variation in fM = fionRfϕ is expected

to stem from either, or both, of the two interfacial sources: (1)

cation-specific surface potential dependence of the silica surfaces,

reflected in fϕ and/or (2) non-electrostatic

cation interactions with the double helix captured by a relative ion

binding affinity factor, given by fion. Our measured fM values for various cationic species relative to those

for the Na+ ion yielded on average  1.1,

1.1,  0.9, and

0.9, and  0.9 (where

0.9 (where  ), and the affinity factors lie in the order

Li > Na > Rb ≈ Cs (Supporting Information Figure S8). These values prove to be close to the “Hofmeister

series”-dependent zeta (ζ) potentials reported for silica

surfaces in alkali metal chloride solutions of concentration 10–3 M to 1 M, where

), and the affinity factors lie in the order

Li > Na > Rb ≈ Cs (Supporting Information Figure S8). These values prove to be close to the “Hofmeister

series”-dependent zeta (ζ) potentials reported for silica

surfaces in alkali metal chloride solutions of concentration 10–3 M to 1 M, where  1.1 ±

0.1 and

1.1 ±

0.1 and  0.8 ±

0.1 (Supporting Information Figure S8b).56,57 Assuming that the reported

trend for the ζ-potential reflects the behavior of the effective

surface electrical potential, ϕs, in our experiments,

our measured trends for fM would suggest

that most of the observed ion-dependent variation in qm stems from the variation of surface potential of silica,

captured by fϕ. Our estimate of

0.9 ≲ fLiR ≲ 1 would therefore point to a 10%

reduction in

0.8 ±

0.1 (Supporting Information Figure S8b).56,57 Assuming that the reported

trend for the ζ-potential reflects the behavior of the effective

surface electrical potential, ϕs, in our experiments,

our measured trends for fM would suggest

that most of the observed ion-dependent variation in qm stems from the variation of surface potential of silica,

captured by fϕ. Our estimate of

0.9 ≲ fLiR ≲ 1 would therefore point to a 10%

reduction in  , at the most, due to binding of

Li+ cations to the molecule, that is,

, at the most, due to binding of

Li+ cations to the molecule, that is,  0.1

0.1 . Therefore, at present, we do

not obtain

evidence of relative cation affinity values, fion, that depart

substantially from 1. To compare these observations with other techniques,

Na23 NMR reports little significant sodium

binding to DNA, with dissociation constants on the order of several

molar.58 MD studies find that while monovalent

cations do reside in the major and minor grooves of DNA, there is

little preferential long-lived binding of monovalent cations (e.g.,

Li+ compared to Na+).59 However, AES reports weak affinities for Li+ cations

corresponding to an amount of bound charge of ≈5–10%

of

. Therefore, at present, we do

not obtain

evidence of relative cation affinity values, fion, that depart

substantially from 1. To compare these observations with other techniques,

Na23 NMR reports little significant sodium

binding to DNA, with dissociation constants on the order of several

molar.58 MD studies find that while monovalent

cations do reside in the major and minor grooves of DNA, there is

little preferential long-lived binding of monovalent cations (e.g.,

Li+ compared to Na+).59 However, AES reports weak affinities for Li+ cations

corresponding to an amount of bound charge of ≈5–10%

of  , and transport measurements

report decreased

electrical mobility of DNA in the presence of Li+ cations.14,60,61 Our observation of an absence

of substantial variation in relative affinity of alkali metal cations,

and a possible weak affinity of Li+ for the double helix,

is thus in broad agreement with previous observations.

, and transport measurements

report decreased

electrical mobility of DNA in the presence of Li+ cations.14,60,61 Our observation of an absence

of substantial variation in relative affinity of alkali metal cations,

and a possible weak affinity of Li+ for the double helix,

is thus in broad agreement with previous observations.

Discussion

It is important to note that although it may in principle be possible

to evaluate electrostatic interaction free energies,  , using

molecular simulations such as Monte

Carlo (MC) or MD methods,53,62,63 these techniques are computationally resource-intensive as the system

size increases. Statistical simulation approaches such as MC require

an exhaustive sampling of the configuration space in order to provide

reliable results with acceptable accuracy.64 On the other hand, PB theory ignores correlations between ions but

is nonetheless expected to provide satisfactory theoretical description

of experiments involving monovalent salts in solution which is typical

for ETe measurements. The PB approximation relies

on the basic assumption that the potential of mean force for each

ion type is equivalent to the mean electrostatic potential.42,65 This assumption neglects all higher-order ion correlations which

manifest both through a long-range coulombic interaction and a short-range

volume-excluded effect.42 These correlations

are particularly important at high concentrations and in the presence

of multivalent ions in solution.66−68 Nevertheless, comparison

of PB ion densities with MC simulations involving finite-sized ions69,70 reveals unexpectedly good agreement, despite the fact that PB theory

is typically thought of as a “point-ion” description

of the problem.42 Although the reason for

this behavior has not been fully understood, it might be attributed

to fortuitous error cancellation within the PB approximation.42

, using

molecular simulations such as Monte

Carlo (MC) or MD methods,53,62,63 these techniques are computationally resource-intensive as the system

size increases. Statistical simulation approaches such as MC require

an exhaustive sampling of the configuration space in order to provide

reliable results with acceptable accuracy.64 On the other hand, PB theory ignores correlations between ions but

is nonetheless expected to provide satisfactory theoretical description

of experiments involving monovalent salts in solution which is typical

for ETe measurements. The PB approximation relies

on the basic assumption that the potential of mean force for each

ion type is equivalent to the mean electrostatic potential.42,65 This assumption neglects all higher-order ion correlations which

manifest both through a long-range coulombic interaction and a short-range

volume-excluded effect.42 These correlations

are particularly important at high concentrations and in the presence

of multivalent ions in solution.66−68 Nevertheless, comparison

of PB ion densities with MC simulations involving finite-sized ions69,70 reveals unexpectedly good agreement, despite the fact that PB theory

is typically thought of as a “point-ion” description

of the problem.42 Although the reason for

this behavior has not been fully understood, it might be attributed

to fortuitous error cancellation within the PB approximation.42

Furthermore, in recent years, several attempts have been made to incorporate missing additional physics into the standard PB model by introducing different forms of modified PB equation.68,71−73 Although these modified PB models provide results that compare well with MC/MD simulations, their application to situations involving monovalent ions and dilute solutions does not lead to results which are significantly different from those of standard PB theory. Thus, in general, the PB approximation gives a satisfactory description for long-range electrostatic interactions of DNA molecules in monovalent electrolytes, which is also in agreement with MC simulations and hypernetted chain approximations.67 The fact that our measurements of the rise per basepair and radius of two classes of the double helix are so close to values known from high-resolution structural biology techniques, such as X-ray crystallography and NMR, may be viewed as evidence of the validity and applicability of the combined experimental and modeling approach described here.

In conclusion, although molecular simulations are gaining dramatically in sophistication and power, field theoretical descriptions of these systems remain important due to the high computational cost of problems involving explicit atoms in a many-body problem. We demonstrate that precise measurements of interaction free energies readily distinguish between structurally or conformationally distinct states of a molecular species. Viewed through the lens of the standing theoretical model for electrostatics, such measurements also provide information on molecular and interfacial structure. Although the approach does not furnish single-atom locations, it is capable of delivering more coarse-grained molecular structural information at high resolution, which could prove useful in analyzing molecular species that are challenging to crystallize or to isotope-label for NMR. Our findings further provide estimates of geometric parameters that describe the far-field properties and interactions of a polyelectrolyte in solution, for example, the effective molecular radius, the SAS, and the radii of ions at an interface. With the surface electrical characteristics of the system (given by fM) determined with high accuracy, we expect that in future, molecular electrometry measurements will be capable of yielding similar information on a molecular species using fewer independent measurements. For example, it may be possible to use our approach to directly measure sequence-dependent differences in the rise per basepair between different oligonucleotide species.74 Furthermore, given the sensitivity of the method to small differences in 3D conformation, for example, in helical geometry as shown in this work, it is likely that molecular electrometry will provide sensitive detection of more complex 3D conformational states and structural features such as loops and bubbles in molecules. Besides, the method is not limited to the study of rod-like molecules but can be readily extended to longer nucleic acids, as long as the measurements are then compared with free energies calculated for relevant molecular structural models.53 Although the present work relies on optical observation of about 1 zmol of a species, label-free optical detection could foster such measurements at the level of one molecule in solution, enabling analysis of biomolecular conformational or structural heterogeneity at the highest sensitivity.75 Finally, since ions and water tend to be disordered, they generally evade detection by high-resolution structural methods. Thus, beyond the structural properties of the molecule, our study furnishes a parameter-free, atomic-level view of the contact region between a molecule and the electrolyte phase (Figure 4b,c), reporting directly on the structure of the “Stern layer” at the liquid–solid interface in solution (Figure 4d).

Materials and Methods

ETe Experimental Procedure: The Measurement of Molecular Escape Time, tesc

Devices for ETe measurements were fabricated using silicon/silicon dioxide and glass substrates as previously described.18 Nanofabricated fluidic slits and nanostructured pocket regions were extensively characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), AFM, and profilometry. We used nanoslits of height 2h = 71–77 nm and a width of about 5 μm and pockets of depth d = 140–160 nm and radii of either 250 or 300 nm. Nanoslits were loaded with a suspension of the molecular species of interest at a concentration of 50–70 pM using pressure-driven flow for about 1 min. The flow was then stopped, and the inlet and outlet reservoirs were filled with the same suspension and sealed to prevent evaporation. The system was allowed to equilibrate for 5–10 min and maintained in an argon atmosphere during the whole measurement.

The salt concentration in the electrolyte was monitored before and after the measurement by measuring solution conductivity with a microconductivity meter (Laquatwin, Horiba Scientific, Japan). The conductivity meter was calibrated for each salt species: LiCl, NaCl, RbCl, and CsCl (Supporting Information Figure S2d). Solution pH was measured before and after the measurement using a micro-pH electrode (InLab, Mettler Toledo, UK) and pH meter (Orion Star A215, Thermo Scientific, UK).

Optical measurements

were performed using wide-field fluorescence

imaging. Fluorescence excitation was achieved by illuminating the

labeled molecules with a 532 nm DPSS laser (MGL_III-532_100 mW, PhotonTec,

Berlin) that was focused at the back aperture of a 60×, NA =

1.35 oil immersion objective (Olympus, UK). Images were acquired using

an sCMOS camera (Prime95B, Photometrics). Time-lapse videos were recorded

using an exposure time  5 ms and a variable lag time between exposures,

5 ms and a variable lag time between exposures,  . The

sampling frequency is the inverse

of

. The

sampling frequency is the inverse

of  , where

, where  =

=  +

+  is

a factor 2–4 smaller than the

average escape time,

is

a factor 2–4 smaller than the

average escape time,  , for

the molecular species of interest.

Typical cycle times were in the range of 40–65 ms for 60 bp

DNA/RNA, 25–40 ms for 40 bp DNA/RNA, and 15–25 ms for

30 bp DNA/RNA. Therefore, typical imaging frequencies were around

15–25 Hz for 60 bp DNA/RNA, 25–40 Hz for 40 bp DNA/RNA,

and 40–67 Hz for 30 bp DNA/RNA.

, for

the molecular species of interest.

Typical cycle times were in the range of 40–65 ms for 60 bp

DNA/RNA, 25–40 ms for 40 bp DNA/RNA, and 15–25 ms for

30 bp DNA/RNA. Therefore, typical imaging frequencies were around

15–25 Hz for 60 bp DNA/RNA, 25–40 Hz for 40 bp DNA/RNA,

and 40–67 Hz for 30 bp DNA/RNA.

Fluorescence images of

molecular trapping were analyzed as described

previously.17 Briefly, regions of interest

(ROIs) centered on the locations of the individual traps were identified

in an automated fashion. Intensity time traces for ROIs were analyzed

using threshold intensity values to identify durations of trapping

events, and the extracted residence times were pooled to construct

escape time histograms (Supporting Information Figure S1a). Operating in the rapid escape regime, corresponding

to average molecular residence times of Δt ≈20–350

ms, we were able to acquire ≈104 escape events within

a total imaging time of 10–20 min for each molecular species

of interest. Fitting the probability density of Δt values with an exponential function of the form  yields the

value of average escape time,

yields the

value of average escape time,  , in any given measurement with an uncertainty

of ≈1% (Supporting Information Figure

S1a).

, in any given measurement with an uncertainty

of ≈1% (Supporting Information Figure

S1a).

Purification and Characterization of DNA and RNA Samples

All nucleic acid fragments were purchased from IBA Lifesciences (Germany) with a single ATTO 532 dye molecule coupled to either one 5′ end or both 5′ termini (Supporting Information Figure S2a). The oligomers were purified with reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography using a Reprosil-Pur 200 C18 AQ column (Dr. Maisch, Germany) and elution with a gradient of acetonitrile in an aqueous 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate solution at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. The integrity of DNA and RNA fragments was examined with 20% polyacrylamide native gel electrophoresis (Supporting Information Figure S2c), and the helical structures (A-form for dsRNA and B-form for dsDNA) were confirmed by acquiring circular dichroism (CD) spectra using a CD spectrometer (Chirascan, Applied Photophysics, UK). Nucleic acid samples in CD spectrometry measurements contained 1 mM NaCl and 1–1.3 mM Tris, similar to the electrometry measurements. CD spectra with a data resolution of 0.5 nm per point were recorded three times for each fragment and averaged (Supporting Information Figure S2b).

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 724180) and from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00657.

Considerations influencing the choice of NA fragments for the study; Converting measured escape times, tesc, to measured molecular effective charge, qm; Accounting for experimental inaccuracies; Inferring values of r, b and fM from measurements of effective charge; Dependence of the inferred rm vs. aH relationship on the assumed values of aH; Comparing the inferred radii of two forms of the double helix; Electrostatic modeling and free energy calculations for B-DNA and A-RNA (PDF)

Author Contributions

M.B. and N.K. performed experiments and analyzed the data. A.B. and R.W.-G. performed molecular modeling. M.B., A.B., and R.W.-G. participated in manuscript preparation. M.K. designed and supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Watson J. D.; Crick F. H. C. Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738. 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing R.; Drew H.; Takano T.; Broka C.; Tanaka S.; Itakura K.; Dickerson R. E. Crystal structure analysis of a complete turn of B-DNA. Nature 1980, 287, 755–758. 10.1038/287755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson R. E.; Drew H. R.; Conner B. N.; Wing R. M.; Fratini A. V.; Kopka M. L. The anatomy of A-, B-, and Z-DNA. Science 1982, 216, 475–485. 10.1126/science.7071593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C.; Marko J. F.; Siggia E. D.; Smith S. Entropic elasticity of lambda-phage DNA. Science 1994, 265, 1599–1600. 10.1126/science.8079175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra N.; Tate S.-i.; Ono A.; Kainosho M.; Bax A. The NMR structure of a DNA dodecamer in an aqueous dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6190–6200. 10.1021/ja000324n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak A. K.; Schröder G. F.; Grubmüller H.; Seidel C. A. M.; Oesterhelt F. Single-molecule FRET measures bends and kinks in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 18337–18342. 10.1073/pnas.0800977105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Meisburger S. P.; Pabit S. A.; Sutton J. L.; Webb W. W.; Pollack L. Ionic strength-dependent persistence lengths of single-stranded RNA and DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 799–804. 10.1073/pnas.1119057109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heenan P. R.; Perkins T. T. Imaging DNA Equilibrated onto Mica in Liquid Using Biochemically Relevant Deposition Conditions. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 4220–4229. 10.1021/acsnano.8b09234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybenkov V. V.; Cozzarelli N. R.; Vologodskii A. V. Probability of DNA knotting and the effective diameter of the DNA double helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993, 90, 5307–5311. 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohs R.; West S. M.; Sosinsky A.; Liu P.; Mann R. S.; Honig B. The role of DNA shape in protein-DNA recognition. Nature 2009, 461, 1248–1253. 10.1038/nature08473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. C. Helical repeat of DNA in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979, 76, 200–203. 10.1073/pnas.76.1.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffeo C.; Schöpflin R.; Brutzer H.; Stehr R.; Aksimentiev A.; Wedemann G.; Seidel R. DNA-DNA interactions in tight supercoils are described by a small effective charge density. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 158101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.158101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X.; Kwok L. W.; Park H. Y.; Lamb J. S.; Andresen K.; Pollack L. Measuring inter-DNA potentials in solution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 138101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.138101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y.; Greenfeld M.; Travers K. J.; Chu V. B.; Lipfert J.; Doniach S.; Herschlag D. Quantitative and comprehensive decomposition of the ion atmosphere around nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14981–14988. 10.1021/ja075020g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]