Abstract

We conducted a systematic literature review on the ethical considerations of the use of contact tracing app technology, which was extensively implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rapid and extensive use of this technology during the COVID-19 pandemic, while benefiting the public well-being by providing information about people’s mobility and movements to control the spread of the virus, raised several ethical concerns for the post-COVID-19 era. To investigate these concerns for the post-pandemic situation and provide direction for future events, we analyzed the current ethical frameworks, research, and case studies about the ethical usage of tracing app technology. The results suggest there are seven essential ethical considerations—privacy, security, acceptability, government surveillance, transparency, justice, and voluntariness—in the ethical use of contact tracing technology. In this paper, we explain and discuss these considerations and how they are needed for the ethical usage of this technology. The findings also highlight the importance of developing integrated guidelines and frameworks for implementation of such technology in the post- COVID-19 world.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10676-022-09659-6.

Keywords: COVID-19, Ethical framework, Privacy, Security, Acceptability, Government surveillance, Transparency, Justice, Voluntariness

Introduction

In the early months of 2020, COVID-19 started spreading around the world, and a pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 (Chen et al., 2021; Machida et al., 2021; Miller & Smith, 2021; SCASSA, 2021). To track the spread of the virus, technologies, including wearable physiological sensors (Natarajan et al., 2020) and digital contact tracing apps (CTA), were leveraged by different groups in more than 100 countries (Gupta et al., 2021; Machida et al., 2021; Mbwogge, 2021; Thomas, 2021). CTA refers to the technology of identifying, assessing, and managing persons who may have come into contact with an infected person to control the spread of the virus by these potential virus carriers (Hoffman et al., 2020). Digital contact tracing via CTA automates the tracing process by leveraging information gathered from sensors, such as GPS and/or Bluetooth, embedded in smartphones and other devices. Experimental evidence shows the potential usefulness of CTA during pandemics (Kawakami et al., 2021; Menges et al., 2021; Rodríguez et al., 2021); however, Menges et al. (2021) discuss significant knowledge gaps regarding the design and the implementation phase of CTA. It is still considered an unproven technology. (Menges et al., 2021) Despite the positive impact of this technology on controlling the spread of the virus and enhancing the healthcare system (Menges et al., 2021), there are critical ethical considerations that affect the usefulness, reliability, and acceptability of this technology. In this paper, we review studies that discuss ethical concerns associated with CTAs during the pandemic and provide suggestions regarding future directions for the post-COVID-19 era.

Contact tracing apps rely on sensitive private data, such as users’ location and their interactions with other people (Chan et al., 2020; Cho et al., 2020). Storing and analyzing such data introduces serious privacy and security issues. There is a tradeoff, which begs ethical scrutiny, between privacy exposure issues and the benefit of CTA to healthcare. (Fahey & Hino, 2020) Furthermore, the interaction between the government and people on how the implementation of the technology could affect citizens’ rights is a critical issue which requires further examination (Basu, 2020a, 2020b; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b). Voluntariness, a choice made without coercion, in the use of CTA is a factor to be carefully examined. For example, impaired voluntariness has been shown to lead to high anxiety levels (Klar & Lanzerath, 2020; Morley et al., 2020). The lack of transparency also causes distrust and failure in further development and implementation of any beneficial AI-driven technology in healthcare system. Acceptability is another consideration that is closely related to privacy, security, transparency, and other ethical concerns. High acceptability and public participation rate are essential for the successful implementation of CTA (Abuhammad et al., 2020). Ranisch et al. (2020) explored the benefits, risks, and limitations of CTA that clearly can play a crucial role in preventing squandering of trust and misconceptions. Basu (2020a, 2020b) argued that the demonstration of trust through an emphasis on transparency is an essential consideration to instilling adequate confidence in individual users.

These apparent ethical issues are mentioned and discussed in a variety of studies, reports, and case studies. The current body of knowledge, however, lacks a systematic review of the ethical considerations of implementing CTA and a discussion of the relationships and possible resolutions of these considerations. Therefore, in this study, we conducted a systematic literature review to (1) reveal the critical ethical considerations in implementing CTA and its costs and benefits, (2) discuss the unique nature of these ethical issues, and (3) provide solutions for the transition to post COVID-19 era.

In addition, these considerations are necessary for the sustainable development of the tracing app technology. Distrust has been recognized as a significant barrier to implementation of AI systems such as CTA. Public trust could greatly impact the future development and usage of CTA (Menges et al., 2021; Oldeweme et al., 2021; Siau & Wang, 2018); hence, these non-technical considerations are vital for advancement of the technical development of CTA. Despite the level of success of CTA in controlling outbreaks and reducing the spread of the virus, without attention to these ethical considerations, the long-term costs associated with wide usage of this technology can significantly outweigh its benefits. Therefore, technology builders, governments, end-users, and any parties involved in building, managing, and using CTA need to take these considerations into account to maximize the effectiveness of the technology while minimizing its short- and long-term negative implications.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows; “Methodology” describes the methodology of the systematic review of the ethical consideration in implementing CTA. “Findings and results” presents the findings and results related to the key values and major ethical considerations and how these considerations should be given enough attention. It also includes cases studies on the applicability of CAT in the COVID-19 era. “Discussion” analytically discusses each of the ethical considerations to elicit the main causes of the concerns, as well as the effectiveness features of CTAs that will be obtained by virtue of acceptability and addressing the practical value conflicts and the probable trade-off between the key values and sub-issues. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions for the post-COVID-19 era are also discussed at the end of this section.

Methodology

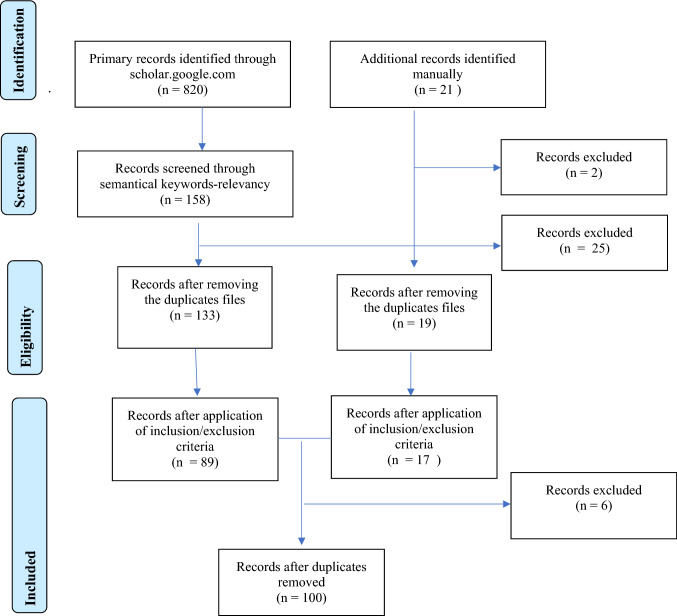

We conducted an inclusive and systematic review of the academic papers, reports, case studies, and ethical frameworks written in English. Given that there is not a specific database on the ethics of COVID-19 in general or ethics of tracing apps technology in particular, we used the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) framework to develop a protocol in this review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Developed PRISMA flow diagram for ethical review of tracing apps technology

In order to conduct a comprehensive review of the relevant studies, we followed two approaches. First, we manually searched for the most related papers on the ethical considerations of CTA: 19 papers were identified through the online search after removal of duplicate files. Secondly, we fulfilled a keyword-based search (using the http://scholar.google.com search engine) to collect all relevant papers on the topic. This search was accomplished using the following keyword phrases: (1) “tracing and COVID 19 ethics,” which provided 19 relevant result pages of Google Scholar, (2) “tracing + COVID-19 + morality,” for which the first five result pages were reviewed, (3) “privacy + COVID-19 + ethics,” for which the first 15 result pages were reviewed; and (4) “digital surveillance + COVID-19 + ethics,” for which the first 13 result pages of Google Scholar were reviewed. The last two keywords, i.e. (3) and (4), were included because of their central role in the research as two main known (based on a preliminary review) ethical considerations of tracing apps technology. Also, the search was suspended within results for each search term due to limited appearances of new relevant papers on the following pages.

The results of the search were 158 relevant papers (which were selected based on the semantical keywords relevancy), out of 820 (which appeared on the result pages). Afterward, the duplicated papers were eliminated from the analysis; we selected the 100 target papers for this systematic review based on the following two inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, articles that were published in academic journals were included. Second, the dominant topic of the papers (or a significant part of it) was the ethics of CTA. To this end, the papers’ main sections were reviewed to understand their dominant topic rather than only relying on the title and papers’ keywords.

Finally, the qualitative analysis on the 100 papers was performed by three researchers who critically read the papers and who developed the eight major key codes as the building blocks of the categorization of the review result in the next step of this research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Major and minor codes included in the reviewed papers

| Major ethical codes | Number of reviewed papers | Minor ethical codes |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy | 33 | Privacy concerns, personal information, anonymity, privacy-impact tradeoff, sharing, privacy from snoopers, privacy from authorities, private and public actors, long-term privacy, decentralized |

| Security | 8 | Security, protection, data loss, unauthorized access, encryption, decentralized, data sharing, anonymized data, third party access, hack |

| Government surveillance | 16 | Government surveillance, surveillance creep, government, civil rights, surveillance |

| Acceptability | 20 | Acceptability, public trust, voluntariness, privacy, beneficence of data, country-wise regulation |

| Transparency | 9 | Transparency, independent monitoring, reliable use, explainability, accountability, responsible data |

| Voluntariness | 10 | Voluntary, solidarity, autonomy, compulsory, anxiety, mandatory use |

| Justice | 10 | Justice, fairness, consistency, inclusion, equality, equity, (non-)bias, (non-) discrimination, diversity, plurality, accessibility, reversibility, remedy, redress, access |

| Case studies | 11 | Social liberty, transparency, ethical and legal challenges |

Findings and results

The emergence of digital public health technologies for dealing with COVID-19 calls for new and appropriate ethical frameworks fitting the unique circumstances. WHO issued Ethical Considerations to Guide the Use of Digital Proximity Tracking Technologies for COVID-19 Contact Tracing in May 2020. Several other studies (Afroogh, 2021; Alanoca et al., 2021; Bruneau et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Leslie, 2020; Morley et al., 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020) have proposed some ethical principles as recommendations for decision-makers in using these technologies. O'Connell et al. (2021) also proposed two kinds of technical considerations and clinical and societal considerations as practical guidelines.

The many questions surrounding ethical and practical dimensions regarding implementation of tracing apps need to be answered by decision-makers (Morley et al., 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020). There are two common value classes addressed by these questions on the ethical usage of tracing app technology. Some of these questions concern substantive values (which refers to the evaluative metrics of the outcomes of measures): public health benefit/effectiveness, harm minimization, privacy, justice/equity/discrimination, liberty/–autonomy/voluntariness, solidarity, surveillance (Morley et al., 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020). Other questions are pertinent to procedural values (which refers to guiding metrics in decision making), such as transparency, proportionality, general trustworthiness, reasonableness, accountability, consistency, engagement, reflexivity (Morley et al., 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020).

In response to these critical questions, the following major ten ethical codes to guide the decision-makers in using the tracing technologies are proposed: (i) all technologies should be temporal in design or practice (Morley et al., 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020), (ii) effectiveness of the technologies needs to be tested before their widespread use to ensure their functionality in public health (Bruneau et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Leslie, 2020; Morley et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020); (iii) data collection and technology use should be limited to the minimum and “necessary amount of data” (World Health Organization, 2020); (iv) any commercial use of the data must be prohibited (Leslie, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020); (v) technologies should respect the individual's autonomy and have to be voluntary for all individuals to download and use the relevant apps to contribute to public health (Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Leslie, 2020; Morley et al., 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020); (vi) all the processing steps, including data collection, data retention, data storage (i.e., decentralized or centralized approach), and data analysis ought to be transparent, informed. and available for individuals (Bruneau et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Leslie, 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020); (vii) high-security measures (including encryption, servers, applications, storage, etc.) must be taken seriously (Bruneau et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Leslie, 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020); (viii) there should be an independent oversight body set to ensure the realization of the ethical considerations. (World Health Organization, 2020); (ix) all technologies should include free participation of public health, legal, and civil society agencies (World Health Organization, 2020). (x) These technologies should be justice-oriented and equity-sensitive and avoid being “digital divide” (Bruneau et al., 2020; Leslie, 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020); and they should not be used as a new tool to increase the government surveillance and power against citizens (Bruneau et al., 2020; Leslie, 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020).

Although the current ethical frameworks have established some general essential recommendations or codes in the application of the tracing app technology, scant attention has been devoted to ethical concerns. Thus, further analysis and explanation of the moral issues and ethical considerations are needed for the effective ethical use of contact tracing apps. In this paper, our intent is not a direct revision of the ethical frameworks or codes nor to directly develop or modify substantial procedural values in the ethical usage of tracing app technology discussed above. Instead, we would focus on a required research step for further development of ethical frameworks, concentrating on the current literature to discern, first, the key values, which are discussed and elaborated based on different methodology or perspectives, such as experimental, statistical, legal, and ethical. Secondly, we would provide a systematic literature review and analytical exploration of the most major findings in all reviewed papers, reports, frameworks, and case studies. These discussions are also aimed at shedding light on the strategies to be implemented for transition to the post-COVID-19 era. Following is a twofold discussion: “Key values”. Key Values, discusses the ethical considerations from an analytical perspective. These considerations are driven by a review of the papers, reports, frameworks, and case studies (Supplementary Information). Secondly, “Case studies”. Case Study, represents some recent case studies of CTA’s application on COVID-19 era.

Key values

Privacy

Several privacy concerns are associated with the contact tracing apps since these apps continuously measure information, including users’ location and their interaction with others (Mbunge, 2020; Mello & Wang, 2020; Scassa, 2021; Subbian et al., 2020). Experimental surveys (Sowmiya et al., 2021) have revealed citizens’ unwillingness to share data due to privacy concerns. Some privacy infringements of these apps, however, are justified given their potentially positive role in saving lives and reducing enormous suffering from adverse impacts of propagation of diseases (Parker et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020; Suh & Li, 2021). Kolasa et al. (2021) verify that “contact tracing apps with high levels of compliance with standards of data privacy tend to fulfill public health interests to a limited extent. Simultaneously, digital technologies with a lower level of data privacy protection allow for the collection of more data.” However, this is considered by Ishmaev et al. (2021) as a “false dilemma” and a tradeoff between privacy concerns associated with tracing apps and their positive health impacts has been an essential topic in ethical considerations among researchers (Bruneau, 2020; Ekong et al., 2020a, 2020b; Klar & Lanzerath, 2020; Leslie, 2020). In light of COVID-19 pandemic, the view of not sharing any private information for any reason has been given less attention since the privacy infringement is less intrusive than population-level lockdowns (Parker et al., 2020). In other words, contingent on taking necessary precautions into account when designing CTA technology, given their positive impact, these apps should be leveraged to reduce the suffering and mortality rate (Basu, 2020a, 2020b; Chan et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Klaaren et al., 2020; Klar & Lanzerath, 2020; Martinez‐Martin et al., 2020). On the other hand, there are some external beliefs against using this technology, given their more complicated and hidden privacy issues (Osman et al., 2020; Rowe, 2020).

Privacy is a broad term that can be defined in different levels: privacy from snoopers, privacy from contact, and privacy from authorities (Cho et al., 2020; Klar & Lanzerath, 2020). The first two can more or less be addressed by appropriate design of the technology, but the privacy from authorities has been a source of concern discussed in different studies (Osman et al., 2020). Critical questions concern the power and control that different actors hold over these technologies. These questions include not only public health authorities but also other governmental agencies (e.g., police, immigration, local authorities), quasi-governmental organizations (e.g., universities), third-sector bodies (e.g., elder care services), technology companies (e.g., providers of operating systems, software, data hosting platforms), and various “shadow” players (e.g., health insurers, food retailers, credit reference agencies, data brokers) (Pagliari, 2020a, 2020b). Furthermore, the presence of private actors like Big Tech companies introduces additional privacy concerns, including unauthorized access to the data, dependency on corporate actors, and manipulating public policy by private actors (Henderson, 2021; Sharon, 2020).

In line with different levels of privacy, long-term privacy concerns are another aspect that should be considered. These issues are not obvious at first glance, and they are not limited to the pandemic period (Parker et al., 2020). The nature of access to and use of the privacy-sensitive personal data, now and in the future, necessitate accountability, transparency, and clear governance processes (Carter et al., 2020). Therefore, tracing technologies not only pose a risk to privacy, but they also put people at risk of surveillance and habituation to security policies, discrimination, and distrust, which may generate further health problems in the long term (Harari, 2020).

Security

In addition to privacy concerns and given the nature of data that can be collected by contact tracing apps on smartphones, there is a need for multiple protections against data loss and unauthorized access to the data (Sowmiya et al., 2021). One way to maintain privacy and security at the same time is to encrypt and store the data on users’ phones (i.e., decentralized approach) (Dwivedi et al., 2020). This information is shared only upon request or when users test positive for the disease (Cho et al., 2020). Storing only anonymized and aggregated data and limiting data storage to the time when a person can be contagious is another way to protect data security (Dubov & Shoptawb, 2020a, 2020b). Security is tightly coupled to privacy by nature; therefore, people who are worried about the security of their private data may be less willing to utilize CTA. Moreover, the tradeoff between effectiveness and security should be considered when designing CTA. Hence, data destruction protocols and use limitations, as well as reliable data security protocols preventing a third party from accessing data, are vital components of ethical framework for digital epidemiology and technological solutions such as CTA (Mbunge, 2020). Furthermore, security issues might cause mental health problems such as stress, anxiety, and depression among users who have serious concerns about sharing their private and personal data (Ahmed et al., 2020). Therefore, significant attention to improving cybersecurity, especially the leveraging of government’s storage and servers, is essential to alleviate such issues (Basu, 2020a, 2020b; Subbian et al., 2020).

Government and epidemic surveillance

Contact tracing systems, such as symptom checkers, are tools of syndromic surveillance that collect, analyze, interpret, and disseminate health-related data (Braithwaite et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b). The COVID-19 pandemic has promoted the implementation of widespread contact-tracing techniques by governments worldwide. In fact, governments are employing surveillance technology, mainly developed through mobile-based applications, to monitor citizens, healthcare organizations, and research institutions in order to identify, locate, and track COVID-19 infected individuals and those exposed to them (Basu, 2020a, 2020b). In some countries, including Singapore, Israel, Italy, South Korea, Russia, Kazakhstan, and the Gulf states, the use of a COVID-19 tracing technology has been declared mandatory (Abuhammad et al., 2020). It has been triggered by the governments as a mechanism to quickly respond by effective identification of virus infections to achieve an efficient allocation of resources to decrease the rate of infection (Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Although COVID-19 surveillance technologies help governments minimize and control the spread of the outbreak, the extensive governmental investments in digital contact-tracing applications have been viewed with both cross-sectional and domain-specific ethical and legal challenges (Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; He et al., 2021). Since the ethical and legal boundaries of implementing digital tools for COVID-19 surveillance and control purposes are unclear, the major suspicion raised by civil liberty groups is due to the perceived threat of mass surveillance (Basu, 2020a, 2020b).

The major concern vis-à-vis civil liberties pertains to the extension of the temporary restrictions of surveillance to a more permanent suspension of rights and liberties, which could lead to inadvertent consequences (Lucivero et al., 2020). In other words, the governments could use or abuse the surveillance technology by increasing monitoring measures even after the end of the pandemic (Abuhammad et al., 2020). Results of a survey conducted by O’Callaghan et al. (2020) showed that 59 percent of people avoid installing a surveillance App due to a fear of the government using the App technology for greater surveillance after the pandemic. History has also proved that surveillance measures emerging during crises that were supposed to expire at a certain time are prone to be renewed or repurposed regularly (Bernard et al., 2020). As an instance, the sweeping intelligence reforms deployed by the United States under the Patriot Act following the 2001 terrorist attacks in New York granted a unique surveillance power to the government, which has never been rolled back (Bernard et al., 2020). This prospect, which is referred to as “surveillance mission creep,” has been raised as a hazard that merits sustained critical attention during COVID-19 (Leslie, 2020). The possibility exists that governments could repurpose the COVID-19 surveillance technologies, which are meant to be solely used for managing the pandemic, for other governmental functions, such as policing techniques (Pagliari, 2020a, 2020b). It is evident that any surveillance mission creep and stealthy insertion of additional app features could erode civil liberties and privacy over time (Pagliari, 2020a, 2020b).

Acceptability

High public acceptance and participation rates are essential for the successful implementation of CTA: “a large number of individuals is required to download contact tracing apps for contact tracing to be effective” (Saw et al., 2021). Overall, when people perceive the benefits and effectiveness of this technology and its positive impact on their health, they are more willing to share their data and accept some of the privacy implications (Martinez‐Martin et al., 2020). However, there is a distinction between public acceptance, which could be stimulated by personal incentives such as monetary compensation, and ethical acceptability, which is not a subjective matter. Acceptability itself is tightly coupled with multiple ethical concepts and trust in CTA (Idrees et al., 2021). Privacy, voluntariness, and beneficence of the data collected by CTA are the most important metrics that affect acceptability of this technology (Abuhammad et al., 2020; Samuel et al., 2021). Therefore, from the perspective of ethics, transparency is paramount: it is the responsibility of all actors, including government and private-sector actors, to keep end users aware of details and implications associated with CTA and to prohibit hiding aspects or communicating false information for the sake of increasing public participation rate (Amann et al., 2021; Bradshaw et al., 2021; Fast & Schnurr, 2021; Von Wyl et al., 2021).

Acceptance rates, regardless of ethical acceptability, vary significantly between countries depending on establishment of sustained and well-founded public trust and confidence (Golbabaei et al., 2020), regulations, social norms, and individuals’ perceptions of costs and benefits (Chan et al., 2020; Parker et al., 2020). Studies in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Jordan have reported support rates ranging from 42 to 80% for CTA (Abuhammad et al., 2020; Lewandowsky et al., 2021; Lo & Sim, 2020; Ranisch et al., 2020). The lack of clarity about COVID-19 tracing contact applications, including objectives, description of the application, how it works, sponsors of this technology, potential burdens to use, possible benefits, and the voluntariness for using such technology, have been found to be the most significant impediments affecting participation rate of such technology (Abuhammad et al., 2020; Leslie, 2020). For example, even though the number of people in Jordan who agreed to the use of COVID-19 contact-tracing technology was 71.6%, the percentage of people who were using this technology was 37.8% (Abuhammad et al., 2020). This participation rate is far less than 60% usage which has been mentioned as the required threshold for achieving maximum effectiveness (Lo & Sim, 2020).

Transparency

Subbian et al. (2020) investigated the transparency and argued that amendments are needed for preventing COVID-19 data from being exploited. Laws and/or regulations may mandate complete transparency about what data are being used and how the data are managed and implemented in both the short and long term (Subbian et al., 2020). Also, it should be clear that using CTA is implemented on a trial basis, and its use should be subject to independent monitoring and evaluation (Lucivero et al., 2020).

Basu (2020a, 2020b) argued that specific consideration is needed for building confidence in the reliable use of tracing apps. The demonstration of trust through an emphasis on transparency in data collection and its application is an essential consideration for instilling adequate confidence in the reasonable individual, even in the absence of voluntariness (SCASSA, 2021). Sweeney (2020) stated that implementing data-driven, machine learning-type models, in general, is very risky. Hence, approaches such as CTA applications require much higher transparency, explainability, and accountability for the type of data currently being collected. In fact, lack of transparent use of CTA apps can result in squandering public trust and raising misconceptions (Ranisch et al., 2020). However, this app had serious security flaws that made private information, such as health and location data, vulnerable to hackers, which put the success of this technology under question. Although the flaw was addressed in the latest version of the app, it is worthwhile to note that, based on the developers’ comments, the pressure to act quickly, underestimating the number of users, and being overwhelmed with work, caused developers to issue software with inadequate security (Singer & Sang-Hun et al., 2020). Although South Korea has become a global example for its creative and transparent handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, the aforementioned security flaw, which happened due to ignoring privacy concerns, once again, raises the question about the tradeoff between privacy concerns and the positive health impacts of CTA. Almeida et al. (2020) studied the challenges that demonstrate the need for new models of responsible and transparent data and technology governance to control SARS-CoV2 and future public health emergencies.

Voluntariness

Studies in ethics of implementing CTA (Abuhammad et al., 2020; Dubov & Shoptawb, 2020a, 2020b; Klar & Lanzerath, 2020) state that voluntariness needs to be preserved at each step of digital contact-tracing implementation—decisions to carry a smartphone, download the contact-tracing app, leave this app operating in the background, react to its alerts, and decisions to share contact logs when testing positive for COVID-19. Certain studies (Klar & Lanzerath, 2020; Morley et al., 2020) take it a step further by connecting the impaired voluntariness to high anxiety levels. Voluntariness is impeded when a government threatens to impose either a lockdown or mandatory use of the tracking apps (Klar & Lanzerath, 2020). Even if people are compelled to act due to a de facto social outcome in which peer pressure and expectations make using the application strongly expected, the use of CTA could be highly problematic (Morley et al., 2020).

Voluntariness and genuine consent-based data sharing is believed to be one of the most ethical approaches to mitigate the cybersecurity and privacy risks of using tracking apps (Dubov & Shoptawb, 2020a, 2020b; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b). Users should consent to share their location data, and the involvement of third-party entities in the data-sharing process should be limited or eliminated (Dubov & Shoptawb, 2020a, 2020b; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b). For example, data collection using GPS data raises privacy concerns, as it can reveal sensitive personal information about individuals, such as visits to a psychiatrist, while Bluetooth-based apps do not track specific locations (Soltani et al., 2020). In the case of Bluetooth-based apps, when phones with the downloaded app come within a certain short distance of each other for a specified period of time, they exchange certain identifiers. When someone reports a positive test, all the phones that recently received an identifier from the infected individual’s phone are notified.

Justice

Public health emergencies actions raise important justice questions because, in these situations, infringements of justice, discrimination, and stigma commonly occur (Emanuel et al., 2020; Parker et al., 2020). CTA contributes to fairness risks over and above the general fairness risk associated with discriminatory mitigation measures. Therefore, there is a risk that CTA increases the ensuring fairness problem (Klenk & Duijf, 2020). Data used in CTA may include ethnic information (race, clan, region), demographic details (gender, age, level of education, marital status), and socioeconomic status, which are subject to a variety of biases (Ntoutsi et al., 2020), can influence the allocation and distribution of COVID-19 resources for treating patients, and can ultimately lead to discrimination and riot (Mbunge, 2020). Gasser et al., (2020a, 2020b) have also investigated the idea that data collection should not be limited to epidemiological factors.

Gasser et al., (2020a, 2020b) have emphasized that social justice and fairness should not get lost in the urgency of this crisis, and they highlight the need for meeting baseline conditions, such as lawfulness, necessity, and proportionality in AI and data processing. There is more concern about how much these technologies cost than about the injustice caused by their use. Progressively, innovation and technology will play a central role in reinforcing a dynamic plan for social justice (Dunlap & McCright, 2010). Hence, more attention needs to be devoted to pressing issues that exist at the nexus of technology and social justice and how social justice can address these issues most effectively. The need for researchers to act quickly and globally in tackling COVID-19 demands unprecedented practices of open research and responsible data sharing. Devakumar et al. (2020) “emphasize that health protection does not only depend on effective universal healthcare systems but relies on social inclusion, justice, and solidarity. They argue that the absence of these values leads to the escalation of inequalities, scapegoating, and long-lasting discrimination, with broad negative public (health) outcomes.” Hendl et al. (2020) investigated that if apps are promoted as an integral part of the COVID-19 pandemic response, this should be done with a clear and explicit commitment to values of health equity, non-discrimination, and solidarity with vulnerable sub-populations.

Case studies

As the implementation of COVID-19 infection tracing technologies has proven successful at controlling the spread of the virus in some countries, such as China and Spain (Rebollo et al., 2021), there has been growing enthusiasm for rapidly expanding such technology to other countries (Abuhammad et al., 2020). Other countries, however, are still under unprecedented uncertainty about how to deploy these technologies to not only limit the spread of COVID-19 but also to respect their citizens’ rights (Pagliari, 2020a, 2020b). In fact, ethical and legal challenges are presented by the implementation of contact-tracing technologies, which call for taking the extra mile to make reasonable efforts to ensure no violation of civil rights will occur. Including, but not limited to, their privacy, liberty, consent, and public benefit. In this regard, some case studies in various countries have examined the ethical and legal implications of COVID-9 tracing technologies and have discussed approaches for improving the technology concerns without inhibiting its benefits to public health.

A recent case study related to India demonstrated that the installation of a government-backed COVID-19 tracing application was mandatory in certain situations. This study argues that the mandatory application requirement represents a legitimate public health intervention during the pandemic (Basu, 2020a, 2020b). In Western countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, the deployment of COVID-19 surveillance technologies has raised issues, such as public trust and data privacy, which necessitated some considerations in the technology design to strike a balance between public benefits and pandemic risks (Pagliari, 2020a, 2020b). Using the contact-tracing technology in Scotland for pandemic management outlines challenges and opportunities for public engagement and raises ethical questions to make informed decisions at multiple levels, from application design to institutional governance (Pagliari, 2020a, 2020b). The COVID-19 surveillance has been shown to significantly improve the capacity and scope of timely outbreak response in Nigeria. Although this technology was used within the current regulation of Nigeria, the existence of guidelines seemed necessary to curb abuse of the data collected through this approach (Ekong et al., 2020a, 2020b). Amann et al. (2021) provide an analytic survey of the media ecosystem’s ideas regarding CTA in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland and conclude that “achieving public consensus on digital contact tracing apps currently seems unlikely. To foster public trust and acceptance, authorities thus need to develop clear and coherent communication strategies that listen to and address public concerns.” Investigating the adoption state of the SwissCOVID app in Switzerland during the pandemic, von Wyl et al. (2021) also argues that “communicating the benefits of digital proximity tracing apps is crucial to promote further uptake and adherence of such apps and, ultimately, enhance their effectiveness to aid pandemic mitigation strategies.”

Discussion

Digital tracing technology has the potential to transcend the tradeoff between saving lives and livelihoods by freeing people from quarantine while containing the virus (Klenk & Duijf, 2020). Digital technologies have been playing an important role in a comprehensive response to outbreaks and pandemics, complementing conventional public health measures and thereby contributing to reducing the human and economic impact of COVID-19. Technology can support non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 epidemic (Dubov & Shoptawb, 2020a, 2020b). An overview of the ways in which technology can support non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 epidemic has also been provided by Budd et al. (2020). However, several requirements exist for these interventions to be ethical and to be able to ensure public confidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is still too early in the COVID-19 pandemic timeline to fully quantify the added value of digital technologies to the pandemic response (Budd et al., 2020).

Some types of COVID-19 technology might lead to the employment of disproportionate profiling, policing, and criminalization of marginalized groups (Hendl et al., 2020). Furthermore, there are technical limitations, dealing with asymptomatic individuals, privacy issues, political and structural responses, ethical and legal risks, consent and voluntariness, abuse of contact tracing apps, and discrimination in using CTA (Mbunge, 2020; Mbunge et al., 2021). The ethical considerations and questions pertinent to tracing technologies date back to old and fundamental ethical considerations enacted to protect basic human and moral values and civil rights. The specific circumstances of COVID-19, however, necessitate revision of previous ethical frameworks and shed light on the significance of the problems. Some of these ethical problems, such as privacy, the uncontrollable increasing power of government surveillance (especially in some countries which are highly susceptible to violating individuals' privacy and human rights), could entail unforeseeable negative impacts on humans’ lives in the near future. Thus, we need to critically contemplate the consequences of any decisions on aspects of citizens' lives in the short, middle, and long term. We should produce inclusive, ethical frameworks for tracing app technologies both in the design/research and practice levels. These frameworks should also include critical considerations to effectively account for various ethical dimensions. Thus, the application of CTA would be effective only if it addresses the five considerations elaborated in the following subsections. Besides ‘Acceptability as a precondition of effectiveness (that directly speaks to the effectiveness of the key values) the other four items elaborate on the value conflicts and the consistency required for any effective CTA applicability.

Privacy in tradeoff with useability

Ethical concerns related to privacy, security, and anonymity are among the significant barriers to the use of contact tracing apps (Andrew Tzer-Yeu Chen, 1967; Elkhodr et al., 2021; Mbunge et al., 2021; Smoll et al., 2021; Urbaczewski & Lee, 2020). Despite these barriers, contact tracing apps have been successfully deployed in several cases for controlling the spread of the virus (Cho et al., 2020; Mbunge, 2020). Hence, the tradeoff between usability and privacy is the most important consideration when using such apps. Technological solutions are one way of addressing certain privacy concerns. For instance, GPS tracing versus Bluetooth tracing, centralized versus decentralized data processing, restricted versus extended data usage, data encryption, and anonymization techniques can be leveraged to reduce privacy risks (Subbian et al., 2020) (Chan et al., 2020). In addition to technological considerations, governments can play an important role in limiting privacy concerns through regulatory efforts (Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b; Subbian et al., 2020; Urbaczewski & Lee, 2020). Given the significant effect of privacy on acceptability of this technology by general population (Subbian et al., 2020; Zimmermann et al., 2021), the government can play an important role in convincing or mandating people to use this technology in the light of Mill’s classic harm principle where the “physical or moral good” of the individual is deemed able to be superseded if necessary for preventing “harm to others.” (Basu, 2020a, 2020b). However, it must be noted that solutions are not one-size-fits-all. In other words, certain solutions that have worked for some countries may not effectively work in other countries with different societal norms. There are significant differences in individuals’ perceptions when evaluating the costs and benefits relating to privacy which may require specific strategies which account for the contextual considerations (Cho et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020).

Data security: centralized and decentralized approaches

Data security is a critical aspect of CTA since the health data collected by smartphones are prone to be hacked or abused by third parties. There are varying opinions about effective ways to improve security and privacy. Some researchers believe in decentralized approaches in which the data are locally saved on the user’s phone and shared upon request, while others think using a centralized data storage in which government’s servers and/or encrypted databases are leveraged can improve the security, especially from snoopers and hackers (Platt et al., 2021). Although governments can claim the notion of improved data security and trust, there are certain concerns associated with governmental access to private data (Greenleaf & Kemp, 2021). Private data, especially data gathered about location and personal interactions, can be used by governments for inappropriate purposes. This becomes a more significant concern if the data storage is not limited to the period of pandemic or the time when a person can be contagious. White and Van Basshuysen (2021a, 2021b) show that “the public at large regard centralized architectures with suspicion.”

Acceptability as a precondition of effectiveness

Acceptability of CTA technology has a direct and significant impact on effectiveness and success of implementing this technology. This technology will be useful at the community level when it is being used by at least 60% of the population (Lo & Sim, 2020). Some countries have addressed this by mandating the usage of contact tracing apps (Cho et al., 2020; Mbunge, 2020; Parker et al., 2020). However, this solution would be less applicable in democratic countries (Basu, 2020a, 2020b; Mello & Wang, 2020). In this case, the role of technology designers and, more importantly, that of governments becomes vital, as they can improve general trust by establishing effective, transparent, accountable, and inclusive oversight as well as transparent, auditable, and easily explained algorithms, the highest possible standards of data security; and effective protections around the ownership uses of data (Parker et al., 2020).

While contact tracing will be successful only when enough people participate, Dubov and Shoptawb (2020a, 2020b) believe that even under conditions of public health emergencies, no one should be obligated to share their personal information. However, (Lucivero et al., 2020) does not totally agree with this argument and believes further studies are needed to explore (1) to what extent the responsibility of a public health matter should be placed on individuals; (2) what this means in terms of accountability (delineating who is legally responsible if something goes wrong). Furthermore, Emanuel et al. (2020) and Parker et al. (2020) believe even increasing the number of participants by providing incentives should be considered carefully on case-by-case basis, as all people might not be able to benefit equally. Klar and Lanzerath (2020) pointed out two factors as prerequisites for the success of the Rakning C-19 app (with the best penetration rate of all contact trackers in the world): (1) the guarantee that all rights will be preserved, and (2) the ensuing trust in the app and the institutions that handle the data. It is clearly specified who has access to the data and how long it will be kept, the data will not be repurposed, and mission creep will be prevented.

Government surveillance and threatening human autonomy

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments’ disaster management has been dependent upon location, health, and population data to forecast the rates of infection, decrease new infections, understand the efficiency of social distancing directives, and improve the efficiency of vaccine development. Nevertheless, the pandemic surveillance technologies are triggering a complex set of ethical and legal hazards exacerbating the increasing challenges to civil liberty, autonomy, privacy, and public trust globally. Merely asserting that an application is voluntary to install or its processes, missions, and functions are visible would not allay the existing concerns (Bernard et al., 2020). Therefore, these technologies must be subject to certain oversight and regulation that oblige the governments to use them ethically, robustly, and transparently and avoid any violation of privacy rights or establishment of a dictatorial police state after COVID-19 outbreak (Abuhammad et al., 2020; Gasser et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Cross-cultural variations and risk–benefit ratio of CTA applications

Analysis of recent COVID-19 surveillance technology debates, controversial programs, and emerging outcomes in comparable countries applying this strategy discloses socio-technical complexities and surprising paradoxes that necessitate further research and that reveal the need for comprehensive, adaptive, and inclusive strategies in using such technology to fight the pandemic (Abuhammad et al., 2020). In China, South Korea, Ireland, Israel, Singapore, Nigeria, and India, highly privacy-invasive COVID-19 tracing approaches have been adopted to manage the spread of the virus (Clarke et al., 2020; Lee & Lee, 2020). In general, their citizens have complied with utilizing the tracing technologies, whether compulsorily or voluntarily. In contrast, considering privacy as a highly ethical issue, as well as public inclination to get rid of government surveillance, is felt very strongly in Europe, where concerns have led some countries, such as Ireland and Germany, to cancel their plans and change course. Different jurisdictions within countries, as well as their specific micro-cultures, play a key role in the implementation of contact-tracing technologies. Moreover, some cases of human rights violations have been made in terms of unethical “legal” rules, which were not developed properly for such a global issue. Therefore, it is vital to assess the performance of actors and practices in the deployment of contact-tracing approaches to understand the real meaning of mandating the use of tracing apps in the lives of people. (Abuhammad et al., 2020).

Concluding remarks and future directions

Review of the research literature on the ethical use of CTA implies that certain consideration is lacking in the incorporation of the technology, and there is an urgent need for developing the metrics and strategies for enabling ethical use of the technology. It is also time to evaluate the functionality of CTA on the basis of the relevant metrics (Durrheim et al., 2021).

The emergency circumstance of the COVID-19 pandemic prevents us from developing comprehensive and inclusive frameworks to address basic and fundamental moral problems. This unique circumstance calls for some short-term practical codes to maximize ethical values in emergency conditions. Such a unique circumstance, however, could be an opportunity to discuss ethical and moral consequences of computational and digital technologies and innovative development, such as empathic and value-sensitive design (Afroogh et al., 2021; Umbrello & van de Poel, 2021), to make sure technology increases the population’s well-being in the long term, and will not be used against them.

Privacy and security are central concerns that can even limit public willingness towards using technologies such as CTA. One of the factors that can improve the security and privacy of this technology and also enhance public’s trust towards these apps is establishing regulations for destroying the collected data after a crisis. CTA can be useful even after the pandemic for tracking down other contagious diseases; however, the costs implied by security and privacy concerns may dominate the health benefits when the pandemic is over. Therefore, it is important to give people the option of whether to share their private data and also to choose the level at which they prefer to share data. A combination of local storage of data on user’s phone along with proper encryption and anonymization can guarantee the users that their private data are safe from third parties as well as from snoopers.

The current costs and benefits of CTA apps are opaque to the end-users. The general public may not be aware of the benefits of these apps and their role in a pandemic; however, privacy and security issues associated with sharing their private data are tangible and concerning. As a result, many users may underestimate the benefits and overestimate the costs, which dissuades them from supporting this technology. Communicating successful examples of the deployment of this technology in cases in which it was effective in detecting outbreak clusters and mitigating impact and containment could change society’s perspective (Basu, 2020a, 2020b; Raman et al., 2021). Overall, making people aware of the technology’s details; algorithms, specifically cybersecurity considerations; and the health impacts could engender acceptability. In this case, it is important not to misrepresent or exaggerate the benefits. Simply conveying the most truthful information to the end-users and allowing them to voluntarily accept this technology are effective approaches for motivating public participation and trust.

There is a need for an independent and trustworthy institution to dispel distrust in CTA in the future. On the one hand, explicitly making the use of tracking apps compulsory seems to be more transparent, and therefore, might be more morally acceptable than an in-principle voluntary but de facto constraining approach (Lucivero et al., 2020). On the other hand, advocating compulsory adoption cannot overcome the fact that certain groups within society may not be able to access this technology, which leads to inequalities (Abuhammad et al., 2020; Lucivero et al., 2020). To this end, an independent and trustworthy institution that can handle the data, ensure privacy, and can support those who might not have access to a smartphone or internet could increase the end users’ trust and the number of volunteers. The recent developments of decentralized solutions seem to alleviate privacy risks as well as dependence on centralized trusted third parties in some sense. However, relying on trusted and independent third parties might be considered as a complementary consideration regardless of the underlying architecture. First, both approaches need trusted servers, though, only the diagnosed positive patient’s record is uploaded to the server in the decentralized system (Wen et al., 2020). Second, neither centralized nor decentralized systems offer an acceptable level of privacy protection, as pointed out by Vaudenay (2020). Third, implementing decentralized models might not be applicable in many places due to the technical difficulties and their available infrastructures (Alanoca et al., 2021). For example, the decentralized method requires a larger amount of data to be downloaded by each device and increases the bandwidth usage, which might be problematic in many countries (Fairbank et al., 2020). Further research is definitely needed to strike an optimal balance (e.g., hybrid models) and to ensure the entity implementing the systems is trustworthy. Last but not least, both methods are dependent on smartphones and obviously exclude anyone who does not own one (often among those most vulnerable, such as older people and migrant workers) (Zastrow, 2020).

Governments willing to implement any of the emerging COVID-19 surveillance technologies need to address their ethical and legal issues. They must put safeguards into place to avoid harm and mitigate the remaining risks. The issues raised around government surveillance remind us that any COVID-19 surveillance program needs to respect people’s privacy, have transparency at its core, protect the collected data, limit surveillance to the minimum necessary to overcome the current crisis, address potential issues of discrimination, adhere to values of democracy, and clarify upfront the duration or timeline of operation. In addition, certain procedural guidance and frameworks must be established as a navigation aid in the form of an iterative set of steps to work through and meet baseline principles, such as adaptivity, flexibility, reflexivity, transparency, accountability, responsiveness.

(Lai et al., 2021) predict the expansion of digital CTA to complement the human-based contact tracing for future pandemics, while the recent case studies have highlighted the importance of transparency, accountability, and stakeholder participation for the credibility of digital tracing strategies in controlling the pandemic. In nondemocratic societies, however, legitimate concerns exist over surveillance creep through applications, and culture of lax civil rights, where political protesters may be tracked and suppressed using such technologies after a pandemic. In democratic societies, there is a need for reasonable efforts to instill confidence among citizens for using these applications in order to effectively manage the pandemic (Basu, 2020a, 2020b). However, it doesn’t mean that “democratic societies” are immune from these technological risks against citizens. Misuse of surveillance, which is occurring broadly by virtue of modern technology, is a global issue that needs to be addressed and considered as a worldwide phenomenon. In this regard, civil society organizations must warn against both the mandatory use of such technologies during pandemics and data misuse by data handlers after the pandemics. Therefore, best practices yet have to emerge for COVID-19 tracing technologies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to an anonymous referee of this journal for their comments and insightful suggestions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saleh Afroogh, Email: safroogh@albany.edu.

Amir Esmalian, Email: amiresmalian@tamu.edu.

Ali Mostafavi, Email: amostafavi@civil.tamu.edu.

Ali Akbari, Email: aliakbari@tamu.edu.

Kambiz Rasoulkhani, Email: kambiz.rasoulkhani@gmail.com.

Shahriar Esmaeili, Email: shahriar110@tamu.edu.

Ehsan Hajiramezanali, Email: ehsanr@tamu.edu.

References

- Abuhammad S, Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH. Covid-19 contact-tracing technology: Acceptability and ethical issues of use. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2020;14:1639–1647. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S276183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afroogh, S. (2021). A contextualist decision theory. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org

- Afroogh S, Esmalian A, Donaldson J, Mostafavi A. Empathic design in engineering education and practice: An approach for achieving inclusive and effective community resilience. Sustainability. 2021;13(7):4060. doi: 10.3390/su13074060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Michelin RA, Xue W, Ruj S, Malaney R, Kanhere SS, Seneviratne A, Hu W, Janicke H, Jha SK. A survey of covid-19 contact tracing apps. IEEE Access. 2020;8:134577–134601. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3010226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alanoca S, Guetta-Jeanrenaud N, Ferrari I, Weinberg N, Çetin RB, Miailhe N. Digital contact tracing against COVID-19: A governance framework to build trust. International Data Privacy Law. 2021;11(1):3–17. doi: 10.1093/idpl/ipab001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida BDA, Doneda D, Ichihara MY, Barral-Netto M, Matta GC, Rabello ET, Gouveia FC, Barreto M. Personal data usage and privacy considerations in the covid-19 global pandemic. Ciencia e Saude Coletiva. 2020;25:2487–2492. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232020256.1.11792020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann J, Sleigh J, Vayena E. Digital contact-tracing during the covid-19 pandemic: An analysis of newspaper coverage in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew Tzer-Yeu Chen KT. Exploring the drivers and barriers to uptake for digital contact tracing. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1967;6(11):951–952. [Google Scholar]

- Basu S. Effective contact tracing for COVID-19 using mobile phones: An ethical analysis of the mandatory use of the Aarogya Setu application in India. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2020;261:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0963180120000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S. Effective contact tracing for COVID-19 using mobile phones: An ethical analysis of the mandatory use of the aarogya setu application in India. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2020;262:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0963180120000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard R, Bowsher G, Sullivan R. COVID-19 and the rise of participatory sigint: An examination of the rise in government surveillance through mobile applications. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(12):1780–1785. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw EL, Ryan RM, Noetel M, Saeri AK, Slattery P, Grundy E, Calvo R. Information safety assurances increase intentions to use COVID-19 contact tracing applications, regardless of autonomy-supportive or controlling message framing. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:3772. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite I, Callender T, Bullock M, Aldridge RW. Automated and partly automated contact tracing: A systematic review to inform the control of COVID-19. The Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2(11):e607–e621. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau GA. The ethical imperatives of the COVID-19 pandemic: A review from data ethics. Revista De Filosofía y Teología. 2020;23:13. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau GA, Gilthorpe M, Müller VC. The ethical imperatives of the COVID-19 pandemic: A review from data ethics. Veritas. 2020;46(46):13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Budd J, Miller BS, Manning EM, Lampos V, Zhuang M, Edelstein M, Rees G, Emery VC, Stevens MM, Keegan N, et al. Digital technologies in the public-health response to COVID-19. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(8):1183–1192. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, K., Berman, G., García-herranz, M., and Sekara, V. (2020). Digital contact tracing and surveillance during COVID-19 general and child-specific ethical issues. Unicef Office of Research, (June).

- Chan, J., Foster, D., Gollakota, S., Horvitz, E., Jaeger, J., Kakade, S., Kohno, T., Langford, J., Larson, J., Sharma, P., Singanamalla, S., Sunshine, J., Tessaro, S. (2020). PACT: Privacy sensitive protocols and mechanisms for mobile contact tracing. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.03544

- Chen S, Waseem D, Xia Z, Tran KT, Li Y, Yao J. To disclose or to falsify: The effects of cognitive trust and affective trust on customer cooperation in contact tracing. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;94:102867. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H., Ippolito, D., and Yu, Y. W. (2020). Contact tracing mobile apps for COVID-19: privacy considerations and related trade-offs. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.11511

- Clarke M, Devlin J, Conroy E, Kelly E, Sturup-Toft S. Establishing prison-led contact tracing to prevent outbreaks of COVID-19 in prisons in Ireland. Journal of Public Health (united Kingdom) 2020;42(3):519–524. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar D, Shannon G, Bhopal SS, Abubakar I. Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. The Lancet Journal. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubov A, Shoptawb S. The value and ethics of using technology to contain the COVID-19 epidemic. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2020;20(7):W7–W11. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1764136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubov A, Shoptawb S. The value and ethics of using technology to contain the COVID-19 epidemic. American Journal of Bioethics. 2020;20(7):W7–W11. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1764136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2010). Climate change denial: Sources, actors and strategies. In Routledge handbook of climate change and society (pp. 240–259). Routledge.

- Durrheim DN, Andrus JK, Tabassum S, Bashour H, Githanga D, Pfaff G. A dangerous measles future looms beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Medicine. 2021;27(3):360–361. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, S. K., Amin, R., Vollala, S., & Chaudhry, R. (2020). Blockchain-based secured event-information sharing protocol in internet of vehicles for smart cities. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 86, 106719.

- Ekong I, Chukwu E, Chukwu M. COVID-19 mobile positioning data contact tracing and patient privacy regulations: Exploratory search of global response strategies and the use of digital tools in Nigeria. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(4):1–7. doi: 10.2196/19139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekong I, Chukwu E, Chukwu M. COVID-19 mobile positioning data contact tracing and patient privacy regulations: Exploratory search of global response strategies and the use of digital tools in Nigeria. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(4):e19139. doi: 10.2196/19139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkhodr M, Mubin O, Iftikhar Z, Masood M, Alsinglawi B, Shahid S, Alnajjar F. Technology, privacy, and user opinions of COVID-19 mobile apps for contact tracing: Systematic search and content analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(2):e23467. doi: 10.2196/23467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, Zhang C, Boyle C, Smith M, Phillips JP. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(21):2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, R. A., & Hino, A. (2020). COVID-19, digital privacy, and the social limits on data-focused public health responses. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fairbank NA, Murray CS, Couture A, Kline J, Lazzaro M. There’s an app for that: Digital contact tracing and its role in mitigating a second wave. Harvard University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fast V, Schnurr D. Incentivizing data donations and the adoption of COVID-19 contact-tracing apps: A randomized controlled online experiment on the German Corona-Warn-app. SSRN Journal. 2021 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3786245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser U, Ienca M, Scheibner J, Sleigh J, Vayena E. Digital tools against COVID-19: Framing the ethical challenges and how to address them. The Lancet Digital Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser U, Ienca M, Scheibner J, Sleigh J, Vayena E. Digital tools against COVID-19: Taxonomy, ethical challenges, and navigation aid. The Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2(8):e425–e434. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbabaei, F., Yigitcanlar, T., Paz, A., & Bunker, J. (2020). Individual predictors of autonomous vehicle public acceptance and intention to use: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 106.

- Greenleaf G, Kemp K. Australia’s ‘COVIDSafe’ law for contact tracing: An experiment in surveillance and trust. International Data Privacy Law. 2021 doi: 10.1093/idpl/ipab009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Pandey G, Chaudhary P, Pal SK. Technological and analytical review of contact tracing apps for COVID-19 management. Journal of Location Based Services. 2021;00(00):1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harari YN. The world after coronavirus. Financial times. 2020;20(03):2020. [Google Scholar]

- He W, Zhang Z, Li W. Information technology solutions, challenges, and suggestions for tackling the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Information Management. 2021;57:102287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J. Patient privacy in the COVID-19 era: Data access, transparency, rights, regulation and the case for retaining the status quo. Health Information Management Journal. 2021;50(1–2):6–8. doi: 10.1177/1833358320966689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendl T, Chung R, Wild V. Pandemic surveillance and racialized subpopulations: Mitigating vulnerabilities in COVID-19 apps. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2020;17:829–834. doi: 10.1007/s11673-020-10034-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AS, Jacobs B, van Gastel B, Schraffenberger H, Sharon T, Pas B. Towards a seamful ethics of Covid-19 contact tracing apps? Ethics and Information Technology. 2020;23:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10676-020-09559-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idrees SM, Nowostawski M, Jameel R. Blockchain-based digital contact tracing apps for COVID-19 Pandemic management: issues, challenges, solutions, and future directions. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2021;9(2):e25245. doi: 10.2196/25245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishmaev G, Dennis M, van den Hoven MJ. Ethics in the COVID-19 pandemic: Myths, false dilemmas, and moral overload. Ethics and Information Technology. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10676-020-09568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami N, Sasaki N, Kuroda R, Tsuno K, Imamura K. The effects of downloading a government-issued COVID-19 contact tracing app on psychological distress during the pandemic among employed adults: Prospective study. JMIR Mental Health. 2021;8(1):e23699. doi: 10.2196/23699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaaren J, Breckenridge K, Cachalia F, Fonn S, Veller M. South Africa’s COVID-19 tracing database: Risks and rewards of which doctors should be aware. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2020;110(7):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar R, Lanzerath D. The ethics of COVID-19 tracking apps—Challenges and voluntariness. Research Ethics. 2020;16(3–4):1–9. doi: 10.1177/1747016120943622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk M, Duijf H. Ethics of digital contact tracing and COVID-19: who is (not) free to go? Ethics and Information Technology. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3595394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolasa K, Mazzi F, Leszczuk-Czubkowska E, Zrubka Z, Péntek M. State of the art in adoption of contact tracing apps and recommendations regarding privacy protection and public health: Systematic review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2021;9(6):e23250. doi: 10.2196/23250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SHS, Tang CQY, Kurup A, Thevendran G. The experience of contact tracing in Singapore in the control of COVID-19: Highlighting the use of digital technology. International Orthopaedics. 2021;45(1):65–69. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04646-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Lee H. Tracing surveillance and auto-regulation in Singapore: ‘smart’ responses to COVID-19. Media International Australia. 2020;177(1):47–60. doi: 10.1177/1329878X20949545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, D. (2020). Tackling COVID-19 through responsible AI innovation: Five steps in the right direction. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.06755

- Lewandowsky S, Dennis S, Perfors A, Kashima Y, White JP, Garrett P, Little DR, Yesilada M. Public acceptance of privacy-encroaching policies to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo B, Sim I. Ethical framework for assessing manual and digital contact tracing for COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;174:395. doi: 10.7326/M20-5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucivero F, Hallowell N, Johnson S, Prainsack B, Samuel G, Sharon T. COVID-19 and contact tracing apps: Ethical challenges for a social experiment on a global scale. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2020;17(4):835–839. doi: 10.1007/s11673-020-10016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida M, Nakamura I, Saito R, Nakaya T, Hanibuchi T, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, Fukushima N, Kikuchi H, Amagasa S, Kojima T, Watanabe H, Inoue S. Survey on usage and concerns of a COVID-19 contact tracing application in Japan. Public Health in Practice. 2021;2:100125. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martin N, Wieten S, Magnus D, Cho MK. Digital contact tracing, privacy, and public health. Hastings Center Report. 2020;50(3):43–46. doi: 10.1002/hast.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbunge E. Integrating emerging technologies into COVID-19 contact tracing: Opportunities, challenges and pitfalls. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020;14(6):1631–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbunge E, Fashoto SG, Batani J. COVID-19 digital vaccination certificates and digital technologies: Lessons from digital contact tracing apps. SSRN Journal. 2021 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3805803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbwogge M. Mass testing with contact tracing compared to test and trace for the effective suppression of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: Systematic review. Jmirx Med. 2021;2(2):e27254. doi: 10.2196/27254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello MM, Wang CJ. Ethics and governance for digital disease surveillance. Science. 2020;368(6494):951–954. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges D, Aschmann H, Moser A, Althaus CL, von Wyl V. The role of the SwissCovid digital proximity tracing app during the pandemic response: Results for the Canton of Zurich. medRxiv. 2021;2:e658. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Smith M. Ethics, public health and technology responses to COVID-19. Bioethics. 2021;35(4):366–371. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley J, Cowls J, Taddeo M, Floridi L. Ethical guidelines for COVID-19 tracing apps. Nature. 2020;582(7810):29–31. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan A, Su H-W, Heneghan C. Assessment of physiological signs associated with COVID-19 measured using wearable devices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2020;3(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-00363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntoutsi E, Fafalios P, Gadiraju U, Iosifidis V, Nejdl W, Vidal M-E, Ruggieri S, Turini F, Papadopoulos S, Krasanakis E, Kompatsiaris I, Kinder-Kurlanda K, Wagner C, Karimi F, Fernandez M, Alani H, Berendt B, Kruegel T, Heinze C, Broelemann K, Kasneci G, Tiropanis T, Staab S. Bias in data-driven artificial intelligence systems—An introductory survey. Wires Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2020;10(3):e1356. doi: 10.1002/widm.1356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan ME, Buckley J, Fitzgerald B, Johnson K, Laffey J, McNicholas B, Nuseibeh B, O’Keeffe D, O’Keeffe I, Razzaq A, Rekanar K, Richardson I, Simpkin A, Abedin J, Storni C, Tsvyatkova D, Walsh J, Welsh T, Glynn L. A national survey of attitudes to COVID-19 digital contact tracing in the Republic of Ireland. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2020;190:863. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, M. E., Vellani, S., Robertson, S., O'Rourke, H. M., & McGilton, K. S. (2021). Going from zero to 100 in remote dementia research: A practical guide. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e24098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oldeweme A, Märtins J, Westmattelmann D, Schewe G. The role of transparency, trust, and social influence on uncertainty reduction in times of pandemics: Empirical study on the adoption of COVID-19 tracing apps. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(2):e25893. doi: 10.2196/25893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman M, Fenton NE, McLachlan S, Lucas P, Dube K, Hitman GA, Kyrimi E, Neil M. The thorny problems of Covid-19 contact tracing apps: The need for a holistic approach. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy. 2020;5:57. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliari C. The ethics and value of contact tracing apps: International insights and implications for Scotland‘s covid-19 response. Journal of Global Health. 2020;10(2):1–18. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliari C. The ethics and value of contact tracing apps: International insights and implications for Scotland’s COVID-19 response. Journal of Global Health. 2020 doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Fraser C, Abeler-Dörner L, Bonsall D. Ethics of instantaneous contact tracing using mobile phone apps in the control of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2020;46(7):427–431. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt M, Hasselgren A, Román-Belmonte JM, de Oliveira M, la Corte-Rodríguez H, Delgado Olabarriaga S, Rodríguez-Merchán EC, Mackey TK. Test, trace, and put on the blockchain?: A viewpoint evaluating the use of decentralized systems for algorithmic contact tracing to combat a global pandemic. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2021;7(4):e26460. doi: 10.2196/26460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman R, Achuthan K, Vinuesa R, Nedungadi P. COVIDTAS COVID-19 tracing app scale—An evaluation framework. Sustainability. 2021;13(5):2912. doi: 10.3390/su13052912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranisch R, Nijsingh N, Ballantyne A, van Bergen A, Buyx A, Friedrich O, Hendl T, Marckmann G, Munthe C, Wild V. Digital contact tracing and exposure notification: Ethical guidance for trustworthy pandemic management. Ethics and Information Technology. 2020;23:285. doi: 10.1007/s10676-020-09566-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo M, Benito RM, Losada JC, Galeano J. Improvement of contact tracing with citizen’s distributed risk maps. Entropy. 2021;23(5):638. doi: 10.3390/e23050638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez P, Graña S, Alvarez-León EE, Battaglini M, Darias FJ, Hernán MA, López R, Llaneza P, Martín MC, Ramirez-Rubio O, Romaní A, Suárez-Rodríguez B, Sánchez-Monedero J, Arenas A, Lacasa L. A population-based controlled experiment assessing the epidemiological impact of digital contact tracing. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20817-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe F. Contact tracing apps and values dilemmas: A privacy paradox in a neo-liberal world. International Journal of Information Management. 2020;55:102178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel G, Roberts SL, Fiske A, Lucivero F, McLennan S, Phillips A, Hayes S, Johnson SB. COVID-19 contact tracing apps: UK public perceptions. Critical Public Health. 2021;0(0):1–13. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2021.1909707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]