Abstract

By using pyrosequencing (i.e., sequencing by synthesis) 106 strains of different serovars of Listeria monocytogenes were rapidly grouped into four categories based on nucleotide variations at positions 1575 and 1578 of the inlB gene. Strains of serovars 1/2a and 1/2c constituted one group, and strains of serovars 1/2b and 3b constituted another group, whereas serovar 4b strains were separated into two groups.

The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive rod-shaped organism that causes the disease listeriosis in both humans and animals. In humans, mainly immunocompromised individuals are affected, and the symptoms include septicemia and/or meningitis. Pregnant women may have abortions, or the newborn child may be seriously compromised (9, 16). It has been suggested that ingestion of contaminated food is an important cause of listeriosis (7).

In investigations of food-borne listeriosis it is essential to type the isolated bacteria. A connection in time and space between patients and implicated food, combined with reliable typing results, is important for establishing the route of infection. Strain characterization is also important when contamination in food production plants is investigated.

L. monocytogenes is an intracellular pathogen that has the ability to induce its own uptake in different types of normally nonphagocytic cells (4, 8). The surface protein internalin, encoded by the inlA gene, mediates invasion of epithelial cells (8). Located downstream of inlA is inlB, which codes for a protein that is involved in uptake and replication of L. monocytogenes in hepatocytes (4, 10). Both inlA and inlB belong to the same gene family (8).

Serotyping and phage typing are established phenotypic methods for typing of L. monocytogenes. However, only a few laboratories have facilities to perform phage typing and complete serotyping. There are also sometimes problems with phage typing reproducibility, and some strains are even nontypeable (11). Recently, genetic methods for typing L. monocytogenes have been introduced, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis is one commonly used method. We have previously shown that the sequence of inlB can be used for typing L. monocytogenes (6). In that study we observed that two nucleotides in the inlB gene, at positions 1575 and 1578, might be sufficient to distinguish four groups of L. monocytogenes strains (6). Strains of serovars 1/2a and 1/2c were grouped together, as were strains of serovars 1/2b and 3b, while strains of serovar 4b were divided into two groups. In the present study, we tested this hypothesis with a novel sequencing-by-synthesis method based on real-time pyrophosphate detection (14). The method is called pyrosequencing and is optimal for sequencing short sequences, including, for example, detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (1). The main application of pyrosequencing so far has been analysis of polymorphisms in the human genome in which single-nucleotide polymorphisms are the most common kind of sequence variation (3).

Bacterial strains.

A total of 106 strains of L. monocytogenes were used in this study. The criteria used to confirm that a strain was a L. monocytogenes strain were those described by Unnerstad et al. (17). The strains were selected from the L. monocytogenes collection of the Department of Food Hygiene, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, and were isolated in different years (1958 to 1998, except for NCTC 7973, which was isolated in 1926) and from different sources (48 strains from food, 43 strains from humans, 12 strains from animals, and 3 strains from the environment). The following serovars were represented: 1/2a (19 strains), 1/2b (16 strains), 1/2c (17 strains), 3a (1 strain), 3b (16 strains), 4b-I (20 strains), and 4b-II (17 strains). In a previous study, the 37 serovar 4b strains were divided into two groups, 4b-I (20 strains) and 4b-II (17 strains), by PCR-restriction enzyme analysis (PCR-REA) of most of the inlB gene and part of the inlA gene (5).

Production of PCR products for pyrosequencing.

Primers LPP1 (5′-ATCGGTCTACCAAGGTAAAA-3′; positions 1518 to 1537) and LPP2 (biotin-5′-CGACCCAACCAATTACTTT-3′; positions 1603 to 1621) were used in a PCR. Sequence data used for primer construction were obtained from Ericsson et al. (6). Each 50-μl PCR mixture contained 1 μl of bacterial cells prepared and denatured as described by Ericsson et al. (5), 5 μl of GeneAmp 10× PCR Gold buffer (PE Biosystems), 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 μM (each) dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP, each primer at a concentration of 0.2 μM, and 1.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (PE Biosystems). The PCR was performed with a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR System 2400. The program was started by incubation at 95°C for 10 min, which was followed by 50 cycles consisting of 95°C for 30 s, 47°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Each PCR product (5 μl) was visualized by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel and staining with ethidium bromide (1.5 μg/ml) for 15 min.

Pyrosequencing.

Biotinylated PCR templates (25 μl) were immobilized on 150 μg of streptavidin-coated paramagnetic Dynabeads M-280 (Dynal AS) in BW buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20; pH 7.6). Samples were incubated for 15 min at 65°C with an Eppendorf Thermomixer Comfort set to constant agitation at 1,400 rpm. After immobilization, the bead-template complexes were washed in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.6) and transferred to 50 μl of 0.5 M NaOH in order to generate single-stranded DNA. After 5 min the samples were washed twice in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.6). The beads were then added to 45 μl of annealing buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate; pH 7.6) containing 15 pmol of the sequencing primer 5′-GCCAAAACACCAATTAC-3′, which was located next to position 1575 and 4 nucleotides from position 1578 in the inlB gene. Annealing took place at 95°C for 1 min, after which the samples were left at room temperature while the sequencing reaction mixture was prepared. All transfers of the bead-template complexes were performed with a PSQ 96 Sample Prep station (Pyrosequencing AB). The sequencing reaction was performed automatically with a PSQ 96 system (Pyrosequencing AB) by using a SNP reagent kit.

Southern blot analysis.

A 104-bp inlB probe labeled with digoxigenin was produced with a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The primers used were LPP1 and LPP4 (5′-CGACCCAACCAATTACTTT-3′; positions 1603 to 1621). Cells of one L. monocytogenes serovar 1/2a strain, one serovar 1/2b strain, one serovar 1/2c strain, one serovar 3b strain, one serovar 4b-I strain, and one serovar 4b-II strain were harvested from 2.5-ml portions of overnight cultures. Total genomic DNA was extracted by the method of Pandiripally et al. (13). Ten micrograms of DNA from each strain was cleaved with EcoRI and, in a second experiment, with NcoI. These two restriction enzymes were chosen because it was assumed that they do not cut within the hybridization target. This assumption was based on sequence data from Gaillard et al. (8) and Ericsson et al. (6). DNA was separated on a 0.9% agarose gel (SeaKem GTG) in 1× TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA) and was then transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) by using a VacuGene XL vacuum blotting system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as recommended in the manufacturer's manual. The filter was prehybridized for 30 min at 40°C in Dig Easy Hyb solution (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The prehybridization solution was replaced by fresh Dig Easy Hyb solution that included the probe, and hybridization was performed at 40°C overnight. The membrane was washed twice in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 15 mM sodium citrate) with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 min at 40°C and twice in 0.5× SSC with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min at 40°C. The digoxigenin-labeled probe was visualized with a Dig luminescent detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

The division of the L. monocytogenes strains based on pyrosequencing of a short region that included positions 1575 and 1578 of the inlB gene correlated with the grouping determined by serotyping. The serovar 4b strains were divided into two groups, while the serovar 1/2a and 1/2c strains were grouped together, as were the serovar 1/2b and 3b strains. The two serovar 4b groups obtained by pyrosequencing were in agreement with the two groups obtained by PCR-REA (5), with a few exceptions. Two strains (SLU 115 and SLU 540) assigned to the serovar 4b-I group by PCR-REA were placed in the serovar 4b-II group by the pyrosequencing method. However, conventional sequencing data for about 400 bp in the same region of these two strains (data not shown) fully supported the pyrosequencing results.

Nucleotides T and A at positions 1575 and 1578, respectively, were characteristic of the serovar 1/2a-serovar 1/2c group, while members of the serovar 1/2b-serovar 3b group had T and T at these positions (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Pyrosequencing of the two serovar 4b groups resulted in a more complex picture. At position 1575 in members of the serovar 4b-I group there was a mixture of C and T, and at position 1578 there was a mixture of G and T. For the serovar 4b-II group, pyrosequencing yielded T at position 1575 and a mixture of G and T at position 1578 (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Nucleotides T and A were the nucleotides obtained after pyrosequencing of the only strain belonging to serovar 3a investigated

TABLE 1.

Pyrosequencing results in relation to serovar and PCR-REA group

| Nucleotide

|

Serovar | No. of strains | PCR-REA group serovar 4b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrosequencing of position 1575 | Pyrosequencing of position 1578 | |||

| C/T | G/T | 4b | 18 | I |

| T | G/T | 4b | 17 | II |

| T | G/T | 4b | 2a | I |

| T | A | 1/2a | 19 | |

| T | A | 1/2c | 17 | |

| T | A | 3a | 1 | |

| T | T | 1/2b | 16 | |

| T | T | 3b | 16 | |

The pyrosequencing data were supported by conventional DNA sequencing.

FIG. 1.

Pyrograms obtained by pyrosequencing of L. monocytogenes strains belonging to different serovars, based on positions 1575 and 1578 of the inlB gene. Incorporated nucleotides are shown below each pyrogram. Relative light units are indicated on the ordinate axes. Additions of enzyme (E) and substrate (S) mixtures and nucleotides are indicated on the horizontal axes. (A) Serovar 1/2a strain SLU 1906 representing the serovar 1/2a-serovar 1/2c group as determined by T and A at the two variable positions. (B) Serovar 3b strain SLU 1182 representing the serovar 1/2b-serovar 3b group as determined by T and T at the two variable positions. (C) Serovar 4b strain SLU 249 representing the serovar 4b-I group as determined by C/T and G/T at the two variable positions. (D) Serovar 4b strain SLU 28 representing the serovar 4b-II group as determined by T and G/T at the two variable positions.

In a previous study (6), we grouped 24 strains in the same categories by sequencing 1,513 bp of the inlB gene. Serovar 1/2a and 1/2c strains were grouped together, as were serovar 1/2b and 3b strains. Molecular grouping of serovars 1/2a and 1/2c together and molecular grouping of serovars 1/2b and 3b together have also been shown by Vines et al. (18), who used restriction fragment length polymorphisms in four virulence-associated genes. Furthermore, these authors assigned serovar 4b to the same group as serovars 1/2b and 3b. In the present study, however, and in the study of Ericsson et al. (6), serovar 4b strains formed two separate groups. Nevertheless, based on the inlB gene sequence, serovar 4b seems to be more closely related to serovars 1/2b and 3b than to serovars 1/2a and 1/2c (6). All serovar 4b strains belonging to phagovar 2389:2425:3274:2671:47:108:340 were assigned to the serovar 4b-II group. Several large outbreaks of listeriosis around the world have been caused by strains belonging to this phagovar, indicating that they may be more likely to cause disease than other strains of L. monocytogenes. Strains of this phagovar are thus included in a group of L. monocytogenes strains that can be identified by pyrosequencing.

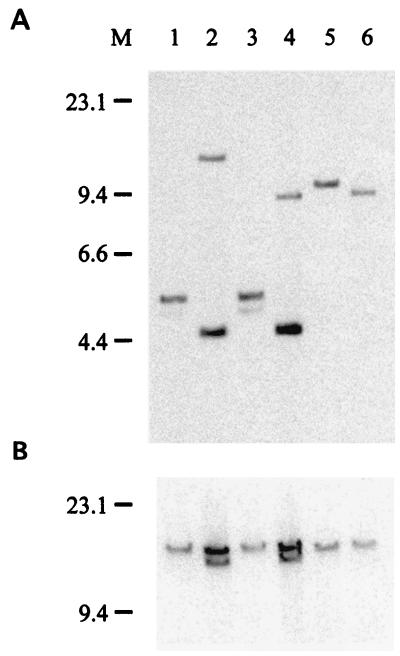

The polymorphisms in serovar 4b visualized by pyrosequencing indicate that the gene segment investigated might be present in at least two variants in the genomes of serovar 4b strains. To test this hypothesis, the 104-bp large fragments that were used as templates for pyrosequencing were cloned and sequenced for one serovar 4b-I strain (SLU 122) and one serovar 4b-II strain (SLU 498). A number of individual clones were generated by using the pGEM-T vector system from Promega. A total of 17 clones were sequenced by the method of Sanger et al. (15), and the results supported the data obtained by pyrosequencing. There were at least two combinations of nucleotides at the two positions investigated in each of the two serovar 4b groups (data not shown). A Southern blot analysis was performed to rule out the possibility that the sequencing data were flawed by errors due to nucleotide misincorporation in the PCR. The pyrosequencing results for serovar 4b strains were supported by the hybridization data obtained with a 104-bp inlB probe. The DNA probe hybridized to a single fragment for each of the genomic digests from serovar 1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c, and 3b strains. In contrast, the probe hybridized to two fragments of different sizes in a Southern blot analysis of the serovar 4b-I and 4b-II strains (Fig. 2). These hybridization results were consistent after genomic digestion with both EcoRI and NcoI. At the time when the probe was constructed, no sequences from genes other than inlB with sufficient homology to the target sequence had been deposited in GenBank. However, after our hybridization experiments were performed, a sequence coding for an amidase, the ami gene, in a serovar 4b strain was deposited in GenBank (accession number AJ276390), and this sequence contains three direct repeats that are approximately 430 bp long from the 3′ end of inlB. Our 104-bp target sequence is contained in the repeats. We concluded that the second signal obtained in Southern blot hybridizations of serovar 4b strains originated from the inlB repeats in the ami gene. Since the restriction enzymes used in the Southern blot experiments did not cleave within the inlB repeats of the ami gene, only one extra band was seen. The stronger signals in Fig. 2A from the serovar 4b strains were probably due to the fact that multiple copies of the probe could bind to each ami gene fragment, compared with the binding of a single copy to the inlB fragments. Some homology between the C-terminal regions of inlB and the gene encoding the amidase in a serovar 1/2a strain has been reported (2, 12), but our target sequence showed only moderate similarity to the ami gene in the serovar 1/2a strain.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot hybridization with a 104-bp inlB probe of EcoRI-digested (A) and NcoI-digested (B) genomic DNAs from L. monocytogenes strains belonging to different serovars. Lane 1, serovar 1/2a strain SLU 83; lane 2, serovar 4b-I strain SLU 520; lane 3, serovar 1/2c strain SLU 524; lane 4, serovar 4b-II strain SLU 559; lane 5, serovar 3b strain SLU 594; lane 6, serovar 1/2b strain SLU 2324; lane M, λ DNA HindIII marker. Molecular sizes (in kilobases) are indicated on the left.

Genetic typing of L. monocytogenes strains by pyrosequencing applied to a short region of the inlB gene was shown to be a useful method for grouping L. monocytogenes strains. Applied to the loci in the inlB gene of L. monocytogenes which we investigated, pyrosequencing may be used for typing as a complement or alternative to serotyping and phage typing. The stability of the loci analyzed seemed to be high, thus making them well suited for sequence tag analyses. Ideally, the results of genotyping methods should agree with the results of traditional grouping methods for serovars since such agreement would make it possible to compare new isolates of L. monocytogenes with the large number of characterized strains available in various strain collections around the world. This study clearly shows that it is possible to use genetic methods whose results agree with the results of serotyping. As exemplified with the serovar 4b group, the discriminatory power of genetic typing can be greater than that of serotyping. Nevertheless, additional target sequences need to be analyzed in order to resolve, for instance, the serovar 1/2b and 3b clusters. This is certainly important when it comes to the epidemiology of listeriosis since most human isolates belong to either serovar 1/2a, 1/2b, or 4b (7, 9). In fully automatic systems like the one used for pyrosequencing, different targets can easily be analyzed in parallel, making complex genotyping straightforward. Thus, the twofold challenge is to identify suitable targets that can connect new isolates with historical records and to identify targets that allow us to see beyond the serovar.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported financially by the Swedish Council for Forestry and Agricultural Research and by the Research Foundation of Ivar and Elsa Sandberg, to which we express our gratitude.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderborn A, Kristofferson A, Hammerling U. Determination of single-nucleotide polymorphisms by real-time pyrophosphate DNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2000;10:1249–1258. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun L, Dramsi S, Dehoux P, Bierne H, Lindahl G, Cossart P. InlB: an invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes with a novel type of surface association. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:285–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4621825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins F S, Brooks L D, Chakravarti A. A DNA polymorphism discovery resource for research on human genetic variation. Genome Res. 1998;8:1229–1231. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dramsi S, Biswas I, Maguin E, Braun L, Mastroeni P, Cossart P. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of inlB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ericsson H, Stålhandske P, Danielsson-Tham M-L, Bannerman E, Bille J, Jacquet C, Rocourt J, Tham W. Division of Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4b strains into two groups by PCR and restriction enzyme analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3872–3874. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3872-3874.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ericsson H, Unnerstad H, Mattsson J G, Danielsson-Tham M-L, Tham W. Molecular grouping of Listeria monocytogenes based on the sequence of the inlB gene. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:73–80. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Frehel C, Gouin E, Cossart P. Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell. 1991;65:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gellin B G, Broome C V. Listeriosis. JAMA. 1989;261:1313–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregory S H, Sagnimeni A J, Wing E J. Internalin B promotes the replication of Listeria monocytogenes in mouse hepatocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5137–5141. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5137-5141.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLauchlin J, Audurier A, Frommelt A, Gerner-Smidt P, Jacquet C, Loessner M J, var der Mee-Marquet N, Rocourt J, Shah S, Wilhelms D. W. H. O. study on subtyping Listeria monocytogenes: results of phage-typing. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlan A M, Foster S J. Molecular characterization of an autolytic amidase of Listeria monocytogenes EGD. Microbiology. 1998;144:1359–1367. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandiripally V K, Westbrook D G, Sunki G R, Bhunia A K. Surface protein p104 is involved in adhesion of Listeria monocytogenes to human intestinal cell line, Caco-2. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:117–124. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-2-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronaghi M, Uhlén M, Nyrén P. A sequencing method based on real-time pyrophosphate. Science. 1998;281:363–365. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seeliger H P R, Jones D. Genus Listeria. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: Williams &Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1235–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unnerstad H, Romell A, Ericsson H, Danielsson-Tham M-L, Tham W. Listeria monocytogenes in faeces from clinically healthy dairy cows in Sweden. Acta Vet Scand. 2000;41:167–171. doi: 10.1186/BF03549648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vines A, Reeves M W, Hunter S, Swaminathan B. Restriction fragment length polymorphism in four virulence-associated genes of Listeria monocytogenes. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]