Abstract

BACKGROUND

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition marked by tics, as well as a variety of psychiatric comorbidities, such as obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCDs), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and self-injurious behavior. TS might progress to treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome (TRTS) in some patients. However, there is no confirmed evidence in pediatric patients with TRTS.

AIM

To investigate the clinical characteristics of TRTS in a Chinese pediatric sample.

METHODS

A total of 126 pediatric patients aged 6-12 years with TS were identified, including 64 TRTS and 62 non-TRTS patients. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS), Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS), and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) were used to assess these two groups and compared the difference between the TRTS and non-TRTS patients.

RESULTS

When compared with the non-TRTS group, we found that the age of onset for TRTS was younger (P < 0.001), and the duration of illness was longer (P < 0.001). TRTS was more often caused by psychosocial (P < 0.001) than physiological factors, and coprolalia and inappropriate parenting style were more often present in the TRTS group (P < 0.001). The TRTS group showed a higher level of premonitory urge (P < 0.001), a lower intelligence quotient (IQ) (P < 0.001), and a higher percentage of family history of TS. The TRTS patients demonstrated more problems (P < 0.01) in the “Uncommunicative”, “Obsessive-Compulsive”, “Social-Withdrawal”, “Hyperactive”, “Aggressive”, and “Delinquent” subscales in the boys group, and “Social-Withdrawal” (P = 0.02) subscale in the girls group.

CONCLUSION

Pediatric TRTS might show an earlier age of onset age, longer duration of illness, lower IQ, higher premonitory urge, and higher comorbidities with ADHD-related symptoms and OCD-related symptoms. We need to pay more attention to the social communication deficits of TRTS.

Keywords: Treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, Child Behavior Checklist, Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale, Social withdrawal, Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Core Tip: This study provides important evidence of treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome (TS) among Chinese patients due to the current shortage of studies based on Chinese samples. We found that the onset age of pediatric patients with treatment-refractory TS (TRTS) might be younger, and they might have a longer duration of illness, a lower intelligence quotient, and a higher premonitory urge, which often fluctuate due to psychosocial factors. Moreover, TRTS children might suffer more emotional and behavioral problems including social communication deficits (such as uncommunicative and social withdrawal), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-related symptoms (hyperactive, aggressive, and delinquent), and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. These were the basic clinical characteristics of TRTS based on Chinese pediatric patients. Unravelling these clinical characteristics is beneficial for the early diagnosis and treatment of TRTS.

INTRODUCTION

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition marked by tics, as well as a variety of psychiatric comorbidities, such as obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCDs), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and self-injurious behavior[1,2]. The worldwide prevalence of tic disorders (TDs) ranges from 0.4 to 1.5%[3]. In a recent report, the prevalence of TS in children and adolescents in China was 0.4%[4]. Some patients with TS fail to respond to traditional treatment, and this condition is referred to as “treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome” (TRTS)[5]. To the best of our knowledge, being refractory to “traditional treatments” (i.e., medicine treatment or behavioral treatment) implies failure to respond to (or have severe side effects from) alpha-adrenergic agonists, typical and atypical antipsychotics, and benzodiazepine, as well as behavioral therapies (i.e., habit-reversal training and exposure type therapy)[6]. It should be noted that one of the unresolved issues is the definition of what constitutes treatment-refractory TS; the most likely reason is the lack of the robust clinical features of TRTS, especially the features associated with the co-occurring other mental disorders[7].

However, different criteria are used to define TRTS in different countries[8]. The most commonly used criterion for TRTS was from the International Deep Brain Stimulation Registry and Database for Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome[9]. It recommended that TRTS should be the major source of disability, with a Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) score of 35/50, failure of conventional therapies (medications from 3 pharmacologic classes), and a trial of CBIT if feasible. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome also reported the criteria of TRTS for European countries[10]. However, no Chinese version of the TRTS criteria has been described. The most likely reason is the lack of confirmed evidence related to TRTS, especially for Chinese patients. Moreover, the different criteria for TRTS were established mostly based on the clinical characteristics of adult patients with Tourette syndrome[8,9]. However, there is no evidence focusing on pediatric patients with TRTS.

Therefore, we need more confirmatory evidence about the clinical characteristics of TRTS. There are some reasons why we need to investigate the clinical characteristics of TRTS. First, TS is frequently encountered by both psychiatrists and neurologists, indicating that TS holds a unique status as a quintessentially neuropsychiatric condition at the interface between neurology (movement disorder) and psychiatry (behavioral condition)[11]. However, few studies have focused on the behavioral and emotional components of TRTS. Second, TS onset occurs between the ages of six and eight years; tics typically start simple and become more complex toward the teenage years[12,13]. Identifying the “indicators” of TRTS in the early stage may help in the treatment of these patients[14]. However, few studies have focused on these potential “indicators” of TRTS. For example, premonitory urge was suggested as an indicator for the severity of tic symptoms[15-17], and confirmatory evidence is required to ascertain if it is also an important sign for TRTS. Third, OCD, ADHD, anxiety, and depression disorders were the top four comorbidities of TS[11], especially TRTS[18], but no evidence links these comorbidities to pediatric TRTS. Fourth, some authors suggested that there might be different subtypes of TS[19,20]. Whether TRTS is different from “pure TS” (only tic symptoms without comorbidities) is unknown. More evidence is needed to explore these differences, especially at the early stage of TRTS. Taken together, we might need more evidence about the clinical characteristics of TRTS, especially in pediatric patients.

In addition, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is one of the most important tools to identify the emotional and behavioral profiles of different mental disorders[21]. It has been suggested that the CBCL can be used to identify ADHD-related[22], obsessive-compulsive[23], anxiety[24], and depression symptoms[25]. It might provide different dimensions of clinical characteristics for TRTS, which can distinguish it from other types of TS.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the clinical characteristics of TRTS in a Chinese pediatric population. We will compare the clinical characteristics (i.e., the onset of tic age, duration of illness, intelligence quotient (IQ), and behavioral and emotional problems) of patients with TRTS and non-TRTS patients. Furthermore, the locations and the frequency of tic onset in TRTS will be reported. The CBCL will be used to present the different dimensions of mental problems between TRTS and non-TRTS. We hypothesized that TRTS patients might show more severe behavioral and emotional problems, especially in the dimensions of obsessive-compulsive, ADHD-related (i.e., hyperactive, aggressive, and delinquent), and depression symptoms. This study will provide important information for a Chinese version of the TRTS criteria, especially for pediatric patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

All participants were recruited from the Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, China from October 1, 2018 to January 1, 2021. Both inclusion and exclusion criteria for TS patients were developed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Aged from 6 to 12 years; and (2) Met the diagnostic criteria for Tourette syndrome according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)[26]. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Epilepsy or any known comorbid brain medical conditions; (2) IQ less than 80; and (3) Serious physical illness.

The criteria for TRTS were as follows: (1) Nonresponsive to trials of medications from dopamine antagonists (typical and atypical) or other medications (i.e., alpha-adrenergic or benzodiazepine) at adequate dosage for at least 6 mo; (2) YGTSS severity total score greater than 35; and (3) Failure following 12 sessions of habit reversal training (if the included TS patients did not meet the criteria for TRTS, they were identified as a non-TRTS group).

The ethics committee of the Beijing Children’s Hospital of Capital Medical University approved this study, and we also obtained written informed consent from the parents or guardians of the enrolled children and adolescents.

Measures

Basic clinical information: A basic information list was used to identify the baseline clinical information, including age, sex, age of onset, duration of illness, factors associated with the fluctuation of tic symptoms (psychosocial factors, i.e., negative emotion or stress; physiological factors, i.e., respiratory tract infection or allergy symptoms), locations of onset of tic, coprolalia frequency, and inappropriate parenting style, among others.

Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: The YGTSS is a semi-structured scale rated by a clinician or trained interviewer. It was developed for assessing the tics observed within 1 wk before the assessment[27,28]. The five dimensions included in the YGTSS are the number, frequency, intensity, complexity, and interference. The total YGTSS score (range: 0-100) is derived by summing the tic severity ranging between 0 and 50 (motor tics range = 0-25 and vocal tics range = 0-25) and the impairment rating score (range = 0-50). The YGTSS is a widely used scale with excellent reliability and validity for assessing children and adolescents with TD[29].

Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale: The Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS) is a nine-item self-report questionnaire measuring premonitory sensations in individuals with tics[30]. Each item is scored from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (very much true). The total score is computed by summing the nine items. Total scores range from 9 to 36, where higher scores represent greater severity of premonitory urges. The PUTS has demonstrated good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity among adolescents between 11 and 16 years of age[31].

Child Behavior Checklist: The CBCL is a widely used questionnaire to assess behavioral and emotional problems. It is often used as a diagnostic screener. The Chinese version of the CBCL contains 118 specific behavioral and emotional problem items and two open-ended items. Each symptom question in the CBCL was scored 0 (not true, as far as you know), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 (very true or often true). Liu completed a regional survey in Shandong and reported that the 2-wk test-retest reliability was 0.90 in 30 children, and the internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s α was 0.93[32,33]. Cronbach’s α was also calculated in the present study, and it was 0.87 for the total scale. The CBCL was completed by the parents or other caregivers for a given child or adolescent. In young patients, the CBCL included eight subscales in the boys’ group (including the Schizoid, Depressed, Uncommunicative, Obsessive-Compulsive, Somatic Complaints, Social-Withdrawal, Hyperactive, Aggressive and Delinquent) and 9 subscales in girls’ groups (including the Depressed, Social-Withdrawal, Somatic Complaints, Schizoid-Obsessive, Hyperactive, Sex Problem, Delinquent, Aggressive, and Cruel).

In addition, the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-4th Edition (WISC-IV) was used to calculate the full IQ[34]. All the included participants were outpatients. The assessments were performed by child psychiatrists after diagnosis was completed.

Statistical analysis

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States, v25.0) to perform the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were performed to identify the basic clinical information, and t tests or χ2 tests were used to compare the different variables of different TS groups. A P-value of 0.05 was set as the significance threshold.

RESULTS

Basic information of the whole sample

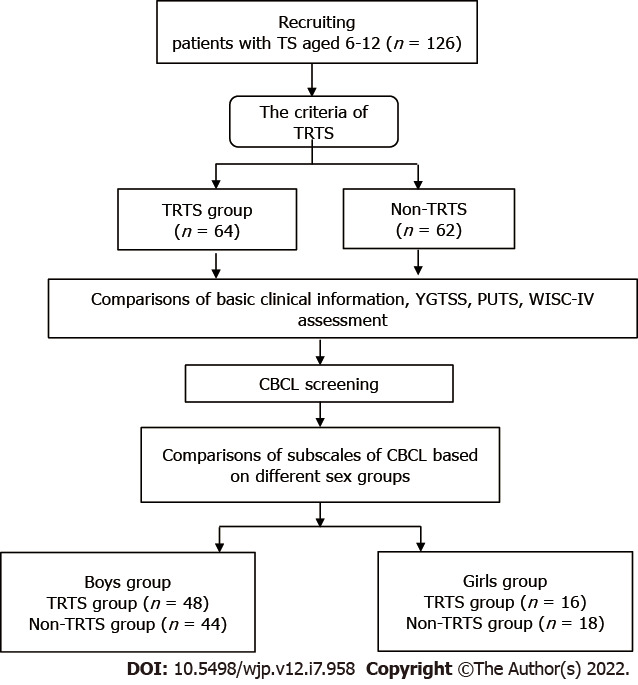

The total sample comprised 126 patients diagnosed with TS, with a male percentage of 73.02%. The mean age of the included patients was 9.24 ± 2.06 years (range, 6-12 years), and the mean duration of illness was 3.83 ± 2.52 years. A total of 64 patients with TS were identified as having TRTS, while 62 non-TRTS patients were also included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of identification of included participants. TRTS: Treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome; YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; PUTS: Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale; WISC-IV: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-4th Edition.

Clinical characteristics of TRTS

After comparing the basic clinical characteristics of the TRTS group with those of the non-TRTS group, we found that in the TRTS group, the onset age was lower (P < 0.001), and the duration of illness was longer than those in the non-TRTS group (P = 0.02). Children in the TRTS group self-reported more fluctuations in conjunction with psychosocial rather than physiological factors (P < 0.001); coprolalia was more often present in the TRTS group than in the non-TRTS group (P < 0.001); and the TRTS group showed more severe functional impairment (P < 0.001). More patients with TRTS showed a positive family history of TS (P = 0.02). The TRTS group showed a lower level of premonitory urge (P < 0.001) and a higher level of tic symptoms (P < 0.001) than the non-TRTS group. Lower IQ was identified in the TRTS group (P < 0.001). In addition, the TRTS group showed more severe tic symptoms and premonitory urges (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic clinical characteristics of patients with treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome and non-treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome patients

|

Related variable

|

TRTS (n = 64)

|

Non-TRTS (n = 62)

|

t

/χ2

|

P

value

|

| Sex (male percentage) | 48 (75.0%) | 44 (71.0%) | 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Age | 9.64 ± 3.01 | 8.82 ± 2.63 | 1.63 | 0.11 |

| Onset age | 5.12 ± 2.81 | 7.29 ± 3.67 | -3.73c | < 0.001 |

| Duration of illness | 4.39 ± 2.17 | 3.27 ± 2.93 | 2.43a | 0.02 |

| Caused by psychosocial factors | 34 (53.1%) | 16 (25.8%) | 9.82c | < 0.001 |

| Caused by physiological factors | 32 (50.0%) | 24 (38.7%) | 1.63 | 0.20 |

| Coprolalia | 30 (46.9%) | 10 (16.1%) | 13.74c | < 0.001 |

| Function impairment | 46 (71.9%) | 28 (45.2%) | 9.27c | < 0.001 |

| Family of TS history | 16 (25%) | 6 (9.7%) | 5.13a | 0.02 |

| YGTSS total | 66.35 ± 4.61 | 39.58 ± 3.97 | 34.88c | < 0.001 |

| YGTSS severity total | 40.41 ± 3.51 | 21.32 ± 2.78 | 33.77c | < 0.001 |

| Impairment | 25.94 ± 3.89 | 18.26 ± 2.21 | 13.57c | < 0.001 |

| PUTS | 26.23 ± 3.28 | 18.33 ± 2.76 | 14.61c | < 0.001 |

| IQ | 92.42 ± 7.63 | 101.05 ± 10.03 | 5.45c | < 0.001 |

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

TRTS: Treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome; YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; PUTS: Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale; IQ: Intelligence quotient.

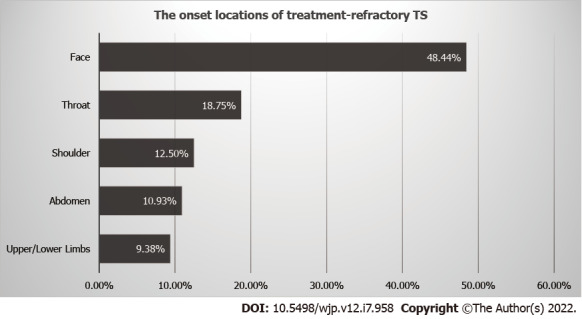

Locations of first-onset tic symptoms in TRTS group

We listed the locations of the first onset of tic symptoms, and the order was the face (48.44%), throat (18.75%), shoulder (12.50%), abdomen (10.93%), and upper/lower limbs (9.38%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of onset locations of tic symptoms in treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome.

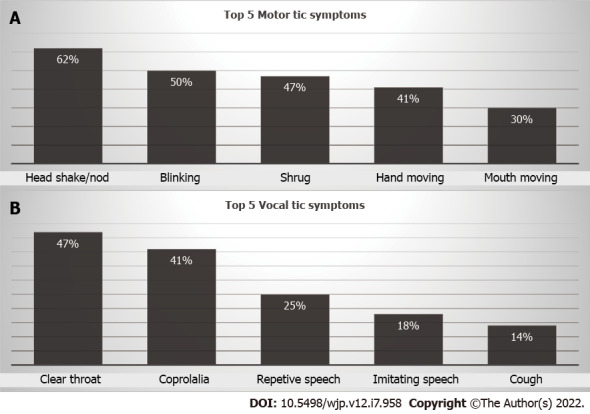

Most frequent tic symptoms in TRTS group

We listed the top five motor and vocal tic symptoms that were frequently present in TRTS patients. The top five motor tic symptoms included head shaking/nodding, blinking, shrugging, hand moving, and mouth moving, while the vocal tic symptoms included clearing the throat, coprolalia, repetitive speech, imitating speech, and cough (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage (top 5) of high frequency motor and vocal tic symptoms in treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome. A: Top 5 high frequency motor tic symptoms in treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome (TRTS); B: Top 5 high frequency vocal tic symptoms in TRTS.

Emotional and behavioral profiles in TRTS group

We found that the total CBCL score was higher in the TRTS group (P < 0.001). We also found that the TRTS patients demonstrated more problems in the “Uncommunicative” (P < 0.001), “Obsessive-Compulsive” (P = 0.001), “Social-Withdrawal” (P < 0.001), “Hyperactive” (P < 0.001), “Aggressive” (P = 0.002), and “Delinquent” (P < 0.001) subscales of the CBCL in the boys group and “Social-Withdrawal” (P = 0.02) in the girls group (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Behavioral and emotional characteristics of treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome and non-treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome in the boys group

|

Subscales of CBCL

|

TRTS (n = 48)

|

Non-TRTS (n = 44)

|

t

|

P

value

|

| Schizoid | 3.75 ± 0.67 | 3.51 ± 0.84 | 1.52 | 0.13 |

| Depressed | 6.17 ±1.24 | 5.81 ± 0.93 | 1.56 | 0.12 |

| Uncommunicative | 3.52 ± 0.89 | 2.81 ± 0.73 | 4.75c | < 0.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 7.69 ± 0.74 | 6.97 ±1.25 | 3.40c | 0.001 |

| Somatic complaints | 3.24 ± 0.68 | 3.44 ± 0.71 | -1.38 | 0.17 |

| Social-withdrawal | 3.78 ± 0.91 | 2.96 ± 0.54 | 5.20c | < 0.001 |

| Hyperactive | 6.59 ± 0.87 | 5.64 ± 1.13 | 4.54c | < 0.001 |

| Aggressive | 14.87 ± 2.01 | 13.55 ± 1.94 | 3.20b | 0.002 |

| Delinquent | 3.49 ± 0.66 | 2.81 ± 1.02 | 3.83c | < 0.001 |

| Total Score | 50.72 ± 6.19 | 43.13 ± 7.16 | 5.45c | < 0.001 |

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; TRTS: Treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome.

Table 3.

Behavioral and emotional characteristics of treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome and non-treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome in the girls group

|

Subscale of CBCL

|

TRTS (n = 16)

|

Non-TRTS (n = 18)

|

t

|

P

value

|

| Depressed | 8.75 ± 1.67 | 7.65 ± 1.84 | 1.82 | 0.08 |

| Social-withdrawal | 6.23 ± 1.17 | 5.24 ± 1.22 | 2.41a | 0.02 |

| Somatic complaints | 3.22 ± 1.03 | 3.05 ± 0.93 | 0.51 | 0.62 |

| Schizoid-obsessive | 2.19 ± 0.44 | 2.07 ± 0.35 | 0.89 | 0.38 |

| Hyperactive | 6.29 ± 1.27 | 5.94 ± 1.13 | 0.85 | 0.40 |

| Sex problem | 0.59 ± 0.17 | 0.56 ± 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.65 |

| Delinquent | 2.79 ± 0.66 | 2.61 ± 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.46 |

| Aggressive | 8.17 ± 1.25 | 7.55 ± 1.04 | 1.58 | 0.12 |

| Cruel | 2.13 ± 0.67 | 2.07 ± 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Total Score | 41.06 ± 5.17 | 36.80 ± 4.65 | 2.53a | 0.02 |

P < 0.05.

CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; TRTS: Treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that pediatric patients always developed TRTS at an earlier age, had a longer duration of illness, had a lower IQ, and had a higher premonitory urge, which often fluctuated due to psychosocial factors. In addition, the incidence of coprolalia seemed higher in the TRTS group. The locations of tics often occur at the face, followed by the throat and shoulder in TRTS; the most common motor tics were nodding or shaking the head, blinking, or shoulder shrugging, while the vocal tics commonly included clearing the throat, coprolalia, and repeated speech. These were the basic clinical characteristics of TRTS based on Chinese pediatric patients. Unraveling these clinical characteristics is beneficial for the early diagnosis and treatment of TRTS.

Based on the results of this study, psychiatric components might be robust features of TRTS. Cavanna et al[11] performed a review of the psychopathological spectrum of TS and reported that the psychiatric components of TS included OCD, ADHD, and affective disorders. A large cross-sectional survey including 1001 TSs found that 85.7% of TSs had at least one psychiatric disorder, and 57.7% had two or more psychiatric disorders[35]. It seems that the most common psychiatric disorders were ADHD and OCD[6].

In this study, we found that children diagnosed with TRTS might suffer more emotional and behavioral problems than non-TRTS children. These included social communication deficits (such as uncommunicative and social withdrawal), ADHD-related symptoms (hyperactive, aggressive, and delinquent), and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The high levels of ADHD-related symptoms and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in TRTS suggest that the comorbid psychiatric conditions of ADHD and OCD seem to be the main clinical characteristics of TRTS. Comorbid ADHD might increase the risk of impulsive behavior (such as running the red light)[36], and these might develop into new psychosocial factors that can cause fluctuations in tic symptoms in TS. Comorbid ADHD might also result in the failure of psychotherapeutic interventions for TS[37]. Moreover, the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in TS was one of the most important predictors of the severity of tic symptoms[38]. Taken together, the comorbid ADHD and OCD might make the traditional treatment of TS harder, which is the most likely reason for the treatment refractoriness of TS.

In addition, in the present study, we found that premonitory urge might be one of the indicators of TRTS. Indeed, obsessive-compulsive symptoms also showed an association with premonitory urge in TS[39]. It seemed that premonitory urge could predict the severity of tic symptoms[40]. This finding suggested that we need to pay attention to the assessment of premonitory urge at the early stage of treatment of TS, which might be an indicator of potential progression to TRTS.

However, we hypothesized that patients diagnosed with TRTS might have more depressive symptoms, but the opposite result was found. Notably, two aspects of social communication, uncommunicative and social withdrawal, were prominent among children diagnosed with TRTS. Regarding the social communication deficits of TS, a recent study reported that TS showed significantly higher mean Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) scores than the general population[41]. These results suggested that more attention should be given to social communication deficits in TS.

Based on the clinical characteristics of TRTS, a younger onset age of tics, a longer duration of illness, comorbidities and social communication deficits may be indicators for TRTS. Up to 70% of the troubles caused by nontic-related functional impairment result from ADHD or OCD[42]. The functional impairment could be caused by both the tics and the comorbidities. Moreover, psychiatric comorbidities might lead to less effective medical treatment or psychotherapeutic treatment[6]. It is indicated that practitioners should pay more attention to early screening and properly treat the comorbidities of patients with TRTS. This could improve the global function and prognosis of TRTS patients with comorbidities. In addition to medicine and psychotherapeutic treatment, there are also some other treatment options. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation can significantly relieve tic and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in TS patients in a meta-analysis[43]. Deep brain stimulation was carefully recommended to patients with TRTS for more consideration of its efficacy and tolerability[44].

In this study, we investigated the clinical characteristics of TRTS, which will provide conforming evidence to the definition of the Chinese version of the criteria for TRTS. According to our study, TRTS might be an important subtype of TS, which differs from “pure TS”. The following aspects might be indicators of pediatric TRTS: An earlier age of onset, longer duration of illness, higher incidence rates of complicated tics such as coprolalia, higher premonitory urge, lower IQ, and more severe functional impairment than other “pure TSs”. Moreover, TRTS is more frequently associated with ADHD-related symptoms, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and social communication deficits. Cumulatively, these clinical characteristics provide important information for the definition of TRTS in China, especially for pediatric patients.

What may account for the social communication deficits in children diagnosed with TRTS? There might be the following three factors. First, both motor and vocal tic symptoms last longer and are more severe in TRTS than in other types of TS. For example, we found that the incidence rates of coprolalia were higher, which brought self-stigma pressure to the patients upon receipt of negative comments such as being called “freak” by peers. A study reported that stigma, social maladjustment, social exclusion, bullying, and discrimination are considered to be caused in large part by misperceptions of the disorder by teachers and peers[45]. Second, psychosocial factors have a huge impact on TRTS. The high comorbidity with ADHD makes children with TRTS suffer poorer test performance and rejections from peers or teachers at school[46]. Moreover, we found that children with TRTS might experience more negative parenting styles, indicating that they might suffer lower self-esteem and become socially withdrawn[47]. Third, it has been confirmed that social cognition deficits can also influence the social communication function of TS[48]. Overall, it indicated the importance of social communication deficit-related symptoms for TRTS.

However, in previous studies, we focused more on ADHD and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in TRTS, and social communication-related problems seemed to be neglected. It should be noted that social communication deficits are crucial signs of functional impairment[45], suggesting that we also need to assess social communication deficits during the assessment of function in TRTS. Therefore, we should pay more attention to social communication deficits in TRTS regardless of the assessment or the treatment.

Some of the following limitations existed in this study. First, the sample size should be larger to increase the effect size. Second, the evaluation tool was limited to the CBCL. Although the CBCL can assess the emotional and behavioral problems associated with TS, more specific tools should be included to evaluate TS comorbidities. Third, this study was a cross-sectional study, and a longitudinal follow-up study will provide more confirmatory evidence in the future.

CONCLUSION

Pediatric TRTS might show an earlier age of onset age, longer duration of illness, lower IQ, higher premonitory urge, and higher comorbidities with ADHD-related symptoms and OCD-related symptoms than ‘pure TS’. Moreover, TRTS shows more social communication deficits that need to be covered in both the assessment and treatment of TRTS. TRTS might be one of the subtypes of TS. We need to develop a proper Chinese version definition of the TRTS in the future, especially for pediatric patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition marked by tics, as well as a variety of psychiatric comorbidities, such as obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCDs), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and self-injurious behavior. However, no Chinese version of the TRTS criteria has been described. Moreover, the different criteria for TRTS were established mostly based on the clinical characteristics of adult patients with Tourette syndrome.

Research motivation

We need more confirmatory evidence about the clinical characteristics of TRTS. However, few studies have focused on the behavioral and emotional components of TRTS. Identifying the “indicators” of TRTS in the early stage may help in the treatment of these patients. Whether TRTS is different from “pure TS” (only tic symptoms without comorbidities) is unknown. More evidence is needed to explore these differences, especially at the early stage of TRTS.

Research objectives

This study aimed to examine the clinical characteristics of TRTS in a Chinese pediatric population, compare the clinical characteristics (i.e., the onset of tic age, duration of illness, intelligence quotient (IQ), and behavioral and emotional problems) of patients with TRTS and non-TRTS patients, and report the locations and the frequency of tic onset in TRTS.

Research methods

A total of 126 pediatric patients aged 6-12 years with TS were identified, including 64 TRTS and 62 non-TRTS patients. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS), Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS), and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) were used to assess these two groups and compared the difference between the TRTS and non-TRTS groups. Descriptive statistics were performed to identify the basic clinical information, and t tests or χ2 tests were used to compare the different variables of different TS groups.

Research results

When compared with the non-TRTS group, we found that the age of onset for TRTS was younger (P < 0.001), and the duration of illness was longer (P < 0.001). TRTS was more often caused by psychosocial (P < 0.001) than physiological factors, and coprolalia and inappropriate parenting style were more often present in the TRTS group (P < 0.001). The TRTS group showed a higher level of premonitory urge (P < 0.001), a lower intelligence quotient (IQ) (P < 0.001), and a higher percentage of family history of TS. The TRTS patients demonstrated more problems (P < 0.01) in the “Uncommunicative”, “Obsessive-Compulsive”, “Social-Withdrawal”, “Hyperactive”, “Aggressive”, and “Delinquent” subscales in the boys group, and “Social-Withdrawal” (P = 0.02) subscale in the girls group.

Research conclusions

Pediatric TRTS might show an earlier age of onset age, longer duration of illness, lower IQ, higher premonitory urge, and higher comorbidities with ADHD-related symptoms and OCD-related symptoms than ‘pure TS’. Moreover, TRTS shows more social communication deficits that need to be covered in both the assessment and treatment of TRTS. TRTS might be one of the subtypes of TS. We need to develop a proper Chinese version definition of the TRTS in the future, especially for pediatric patients.

Research perspectives

In previous studies, we focused more on ADHD and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in TRTS, and social communication-related problems seemed to be neglected. It should be noted that social communication deficits are crucial signs of functional impairment, suggesting that we also need to assess social communication deficits during the assessment of function in TRTS. Therefore, we should pay more attention to social communication deficits in TRTS regardless of the assessment or the treatment.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beijing Children’s Hospital (No. 2021-82171538).

Conflict-of-interest statement: All other authors report no conflict of interest for this article.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 21, 2021

First decision: March 13, 2022

Article in press: June 27, 2022

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aydin S, Turkey; Hazafa A, Pakistan S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Ying Li, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children's Hospital, Beijing 100045, China.

Jun-Juan Yan, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children's Hospital, Beijing 100045, China.

Yong-Hua Cui, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children's Hospital, Beijing 100045, China. cuiyonghua@bch.com.cn.

Data sharing statement

Data is available upon reasonable request for clearly defined scientific purposes from the corresponding author at cuiyonghua@bch.com.cn.

References

- 1.Set KK, Warner JN. Tourette syndrome in children: An update. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2021;51:101032. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stafford M, Cavanna AE. Prevalence and clinical correlates of self-injurious behavior in Tourette syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;113:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson MM. A personal 35 year perspective on Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidities, and coexistent psychopathologies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:68–87. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li F, Cui Y, Li Y, Guo L, Ke X, Liu J, Luo X, Zheng Y, Leckman JF. Prevalence of mental disorders in school children and adolescents in China: diagnostic data from detailed clinical assessments of 17,524 individuals. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63:34–46. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porta M, Sassi M, Menghetti C, Servello D. The need for a proper definition of a "treatment refractoriness" in tourette syndrome. Front Integr Neurosci. 2011;5:22. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2011.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kious BM, Jimenez-Shahed J, Shprecher DR. Treatment-refractory Tourette Syndrome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szejko N, Lombroso A, Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF. Refractory Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Many Pieces That Define the Puzzle. Front Neurol. 2020;11:589511. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.589511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanna AE, Eddy CM, Mitchell R, Pall H, Mitchell I, Zrinzo L, Foltynie T, Jahanshahi M, Limousin P, Hariz MI, Rickards H. An approach to deep brain stimulation for severe treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome: the UK perspective. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:38–44. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2010.534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrock LE, Mink JW, Woods DW, Porta M, Servello D, Visser-Vandewalle V, Silburn PA, Foltynie T, Walker HC, Shahed-Jimenez J, Savica R, Klassen BT, Machado AG, Foote KD, Zhang JG, Hu W, Ackermans L, Temel Y, Mari Z, Changizi BK, Lozano A, Auyeung M, Kaido T, Agid Y, Welter ML, Khandhar SM, Mogilner AY, Pourfar MH, Walter BL, Juncos JL, Gross RE, Kuhn J, Leckman JF, Neimat JA, Okun MS Tourette Syndrome Association International Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Database and Registry Study Group. Tourette syndrome deep brain stimulation: a review and updated recommendations. Mov Disord. 2015;30:448–471. doi: 10.1002/mds.26094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller-Vahl KR, Cath DC, Cavanna AE, Dehning S, Porta M, Robertson MM, Visser-Vandewalle V ESSTS Guidelines Group. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part IV: deep brain stimulation. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavanna AE, Rickards H. The psychopathological spectrum of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:1008–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martino D, Madhusudan N, Zis P, Cavanna AE. An introduction to the clinical phenomenology of Tourette syndrome. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;112:1–33. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-411546-0.00001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschtritt ME, Dy ME, Yang KG, Scharf JM. Child Neurology: Diagnosis and treatment of Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2016;87:e65–e67. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson MM. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the complexities of phenotype and treatment. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2011;72:100–107. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2011.72.2.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu Y, Li Y, Cui Y. Correlation between premonitory urges and tic symptoms in a Chinese population with tic disorders. Pediatr Investig. 2020;4:86–90. doi: 10.1002/ped4.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyriazi M, Kalyva E, Vargiami E, Krikonis K, Zafeiriou D. Premonitory Urges and Their Link With Tic Severity in Children and Adolescents With Tic Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:569. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Wang F, Liu J, Wen F, Yan C, Zhang J, Lu X, Cui Y. The Correlation Between the Severity of Premonitory Urges and Tic Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29:652–658. doi: 10.1089/cap.2019.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Ramirez D, Jimenez-Shahed J, Leckman JF, Porta M, Servello D, Meng FG, Kuhn J, Huys D, Baldermann JC, Foltynie T, Hariz MI, Joyce EM, Zrinzo L, Kefalopoulou Z, Silburn P, Coyne T, Mogilner AY, Pourfar MH, Khandhar SM, Auyeung M, Ostrem JL, Visser-Vandewalle V, Welter ML, Mallet L, Karachi C, Houeto JL, Klassen BT, Ackermans L, Kaido T, Temel Y, Gross RE, Walker HC, Lozano AM, Walter BL, Mari Z, Anderson WS, Changizi BK, Moro E, Zauber SE, Schrock LE, Zhang JG, Hu W, Rizer K, Monari EH, Foote KD, Malaty IA, Deeb W, Gunduz A, Okun MS. Efficacy and Safety of Deep Brain Stimulation in Tourette Syndrome: The International Tourette Syndrome Deep Brain Stimulation Public Database and Registry. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:353–359. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eapen V, Robertson MM. Are there distinct subtypes in Tourette syndrome? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1431–1436. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S72284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschtritt ME, Darrow SM, Illmann C, Osiecki L, Grados M, Sandor P, Dion Y, King RA, Pauls D, Budman CL, Cath DC, Greenberg E, Lyon GJ, Yu D, McGrath LM, McMahon WM, Lee PC, Delucchi KL, Scharf JM, Mathews CA. Genetic and phenotypic overlap of specific obsessive-compulsive and attention-deficit/hyperactive subtypes with Tourette syndrome. Psychol Med. 2018;48:279–293. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biederman J, DiSalvo M, Vaudreuil C, Wozniak J, Uchida M, Yvonne Woodworth K, Green A, Faraone SV. Can the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) help characterize the types of psychopathologic conditions driving child psychiatry referrals? Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. 2020;8:157–165. doi: 10.21307/sjcapp-2020-016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Kendrick E, Klein KL, Faraone SV. The CBCL as a screen for psychiatric comorbidity in paediatric patients with ADHD. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:1010–1015. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.056937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudziak JJ, Althoff RR, Stanger C, van Beijsterveldt CE, Nelson EC, Hanna GL, Boomsma DI, Todd RD. The Obsessive Compulsive Scale of the Child Behavior Checklist predicts obsessive-compulsive disorder: a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aschenbrand SG, Angelosante AG, Kendall PC. Discriminant validity and clinical utility of the CBCL with anxiety-disordered youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34:735–746. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Najman JM, Hallam D, Bor WB, O'Callaghan M, Williams GM, Shuttlewood G. Predictors of depression in very young children--a prospective study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PA . American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, Cohen DJ. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:566–573. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen F, Gu Y, Yan J, Liu J, Wang F, Yu L, Li Y, Cui Y. Revisiting the structure of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) in a sample of Chinese children with tic disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:394. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Sajid M, Allen P, Roberti JW, Goodman WK. Reliability and validity of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:486–491. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods DW, Piacentini J, Himle MB, Chang S. Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS): initial psychometric results and examination of the premonitory urge phenomenon in youths with Tic disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:397–403. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200512000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Openneer TJC, Tárnok Z, Bognar E, Benaroya-Milshtein N, Garcia-Delgar B, Morer A, Steinberg T, Hoekstra PJ, Dietrich A and the EMTICS collaborative group. The Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale in a large sample of children and adolescents: psychometric properties in a developmental context. An EMTICS study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:1411–1424. doi: 10.1007/s00787-019-01450-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung PW, Kwong SL, Tang CP, Ho TP, Hung SF, Lee CC, Hong SL, Chiu CM, Liu WS. Test-retest reliability and criterion validity of the Chinese version of CBCL, TRF, and YSR. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:970–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Kurita H, Guo C, Miyake Y, Ze J, Cao H. Prevalence and risk factors of behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese children aged 6 through 11 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:708–715. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H. The revised Chinese version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Fourth Version (WISC-IV) J Psych Science. 2009:1177–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, Dion Y, Grados MA, Illmann C, King RA, Sandor P, McMahon WM, Lyon GJ, Cath DC, Kurlan R, Robertson MM, Osiecki L, Scharf JM, Mathews CA Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:325–333. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mataix-Cols D, Brander G, Chang Z, Larsson H, D'Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Sidorchuk A, Fernández de la Cruz L. Serious Transport Accidents in Tourette Syndrome or Chronic Tic Disorder. Mov Disord. 2021;36:188–195. doi: 10.1002/mds.28301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyon GJ, Coffey BJ. Complex tics and complex management in a case of severe Tourette's disorder (TD) in an adolescent. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:469–474. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.19402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kano Y, Matsuda N, Nonaka M, Fujio M, Kuwabara H, Kono T. Sensory phenomena related to tics, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and global functioning in Tourette syndrome. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;62:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan J, Yu L, Wen F, Wang F, Liu J, Cui Y, Li Y. The severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Tourette syndrome and its relationship with premonitory urges: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20:1197–1205. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2020.1826932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Woods DW, Gu Y, Yu L, Yan J, Wen F, Wang F, Liu J, Cui Y. Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale: A Preliminary Report. Front Psychol. 2021;12:573803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.573803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eapen V, McPherson S, Karlov L, Nicholls L, Črnčec R, Mulligan A. Social communication deficits and restricted repetitive behavior symptoms in Tourette syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2151–2160. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S210227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storch EA, Lack CW, Simons LE, Goodman WK, Murphy TK, Geffken GR. A measure of functional impairment in youth with Tourette's syndrome. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:950–959. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu CW, Wang LJ, Lin PY. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for Tourette syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2018;11:1110–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szejko N, Worbe Y, Hartmann A, Visser-Vandewalle V, Ackermans L, Ganos C, Porta M, Leentjens AFG, Mehrkens JH, Huys D, Baldermann JC, Kuhn J, Karachi C, Delorme C, Foltynie T, Cavanna AE, Cath D, Müller-Vahl K. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders-version 2.0. Part IV: deep brain stimulation. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:443–461. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01881-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eapen V, Cavanna AE, Robertson MM. Comorbidities, Social Impact, and Quality of Life in Tourette Syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:97. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humphreys KL, Gabard-Durnam L, Goff B, Telzer EH, Flannery J, Gee DG, Park V, Lee SS, Tottenham N. Friendship and social functioning following early institutional rearing: The role of ADHD symptoms. Dev Psychopathol. 2019;31:1477–1487. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.hahsavari MH, Pirani Z, Taghvaee D and Abdi M. Study of the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relation of parenting styles with social participation of adolescents. International Archives Health Sciences. 2021;8:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eddy CM. Social cognition and self-other distinctions in neuropsychiatry: Insights from schizophrenia and Tourette syndrome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;82:69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request for clearly defined scientific purposes from the corresponding author at cuiyonghua@bch.com.cn.