Abstract

A soil bacterium (designated strain SRS2) able to metabolize the phenylurea herbicide isoproturon, 3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (IPU), was isolated from a previously IPU-treated agricultural soil. Based on a partial analysis of the 16S rRNA gene and the cellular fatty acids, the strain was identified as a Sphingomonas sp. within the α-subdivision of the proteobacteria. Strain SRS2 was able to mineralize IPU when provided as a source of carbon, nitrogen, and energy. Supplementing the medium with a mixture of amino acids considerably enhanced IPU mineralization. Mineralization of IPU was accompanied by transient accumulation of the metabolites 3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1-methylurea, 3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-urea, and 4-isopropyl-aniline identified by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis, thus indicating a metabolic pathway initiated by two successive N-demethylations, followed by cleavage of the urea side chain and finally by mineralization of the phenyl structure. Strain SRS2 also transformed the dimethylurea-substituted herbicides diuron and chlorotoluron, giving rise to as-yet-unidentified products. In addition, no degradation of the methoxy-methylurea-substituted herbicide linuron was observed. This report is the first characterization of a pure bacterial culture able to mineralize IPU.

The phenylurea herbicide isoproturon, 3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (IPU), which is used for pre- and postemergence control of annual grasses and broad-leaved weeds in wheat, rye, and barley crops, is among the most extensively used pesticides in conventional agriculture in Europe (34). Ecotoxicological data suggest that IPU and some of its metabolites are harmful to aquatic invertebrates (20), freshwater algae (25), and microbial activity (28). IPU is also suspected of being carcinogenic (2, 14). As a result of its widespread and repeated use, IPU is frequently detected in groundwater and surface waters in Europe in levels exceeding the European Commission drinking water limit of 0.1 μg l−1 (23, 33, 34).

Degradation of IPU in agricultural soils occurs predominantly by microbiological processes (6, 22). Several studies have demonstrated a slow natural attenuation rate in various soils and subsurface environments with respect to mineralization of the phenyl structure (4, 15, 17, 18, 26, 35). The detection of IPU as an environmental pollutant and its apparently low mineralization potential has stimulated research aimed at isolating and characterizing microbial cultures able to mineralize IPU. Enrichment culture techniques have been used with varied success in attempts to isolate IPU-degrading microorganisms. In previous studies, slurries of mineral media and soils from different agricultural fields failed to degrade IPU (4, 19, 35). Enrichment on the IPU metabolite 3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1-methylurea (MDIPU) as the sole source of carbon and energy recently yielded a mixed bacterial culture able to perform growth-linked mineralization of MDIPU and 4-isopropyl-aniline (4IA) but with no degradation activity toward IPU (35). Several soil bacteria (7, 31) and soil fungi (3) are known to be able to catalyze transformation of the dimethylurea side chain of IPU, but there are no reports of microorganisms in pure culture able to mineralize the phenyl structure of IPU or any other phenylurea herbicides. Recently, El-Fantroussi (9) suggested that the lack of success in isolating pure cultures of phenylurea-mineralizing bacteria could be attributable to the involvement of consortia rather than single bacteria in the complete degradation.

In the present study we describe the isolation and characterization of an IPU-mineralizing Sphingomonas sp. (designated strain SRS2) from a British agricultural field that had previously been treated with IPU for several years. The study is the first to describe the isolation and characterization of a pure bacterial culture able to mineralize a phenylurea herbicide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

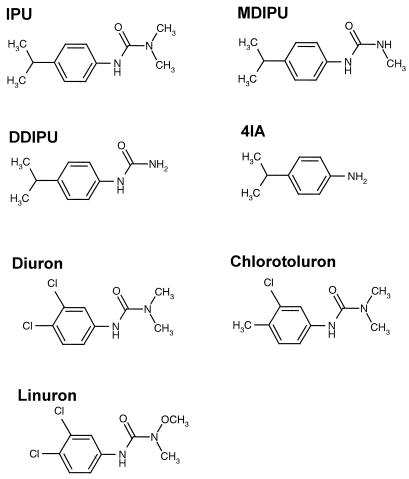

Analytical-grade IPU (99.5% purity, 55-mg liter−1 water solubility at 20°C), MDIPU (99.9% purity), 3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-urea (DDIPU) (98.3% purity), 4IA (99.5% purity), diuron (97.5% purity, 42-mg liter−1 water solubility at 25°C), linuron (99.8% purity, 81-mg liter−1 water solubility at 24°C), and chlorotoluron (97.5% purity, 70-mg liter−1 water solubility at 20°C) were purchased from Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH (Augsberg, Germany). [phenyl-U-14C]IPU (914 MBq mmol−1, 97% radiochemical purity) (14C-IPU) was obtained from Amersham Life Science (Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). [phenyl-U-14C]MDIPU (4.42 MBq mg−1, 99% radiochemical purity) (14C-MDIPU) was purchased from the Institute of Isotopes (Budapest, Hungary). [phenyl-U-14C]4IA (773.3 MBq mmol−1, >98% radiochemical purity) (14C-4IA) was purchased from International Isotope (Munich, Germany). The molecular structures of the compounds are presented in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Molecular structure of the phenylurea herbicides diuron, linuron, and isoproturon (IPU) and the IPU metabolites MDIPU, DDIPU, and 4IA.

Enrichment and growth media.

The mineral salt medium (MS) used for the enrichment and pure culture studies was modified from the HCMM2 medium described by Ridgway et al. (30) by excluding KNO3 and (NH4)SO4 and adding 1.0 ml of filter-sterilized FeCl3 · 6H2O solution (5.14 mg liter−1) after the medium was autoclaved. For the pure culture studies, MS was supplemented with 100 mg of Casamino Acids (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) liter−1 (MS-CA) or a defined amino acid mixture (MS-A19) containing 5.0 mg of l-lysine, l-alanine, l-aspartic acid, l-arginine, l-cysteine, glycine, l-histidine, l-glutamic acid, l-leucine, l-tyrosine, l-threonine, l-tryptophane, l-serine, l-valine, l-phenylalanine, l-proline, l-methionine, and l-isoleucine (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Aurora, Ohio) liter−1. Different media with a reduced number of amino acids were made by systematically excluding individual amino acids. MS-A2, which was used for studying the range of compounds degraded by strain SRS2, contained 5.0 mg of l-methionine and glycine liter−1. R2A-based broth (R2B) for growth of the bacterium was prepared according to the method of Reasoner and Geldreich (27).

The enrichment cultures where plated on 1/10-strength tryptic soy agar (TSA), Luria-Bertani agar (LB), Bacto nutrient agar (NA), R2A (27), and water agar (WA; Bitek agar [15 g liter−1] in MilliQ-water); all products were from Difco. IPU-containing agar (IPU agar) were made from 15 g of Noble agar (Difco) liter−1 in MS medium supplemented with IPU (50 mg liter−1). The IPU agar was prepared by transferring autoclaved and cooled MS (<50°C) into sterilized 1-liter flasks with solid IPU. Before preparation of the plates the IPU was dissolved in the agar by incubation at 50°C for 24 h.

Enrichment culture.

Soils were sampled from the top layer (0 to 25 cm) of two previously IPU-treated agricultural fields located near Græse (Denmark) and near Wellesbourne (site E6, Deep Slade, United Kingdom). Details of the soil properties and the sampling procedure have been described previously (35, 39). Sterilized 100-ml flasks containing IPU (25 mg liter−1) in 25 ml of MS were inoculated with 5 g of soil and sealed with airtight stoppers. The IPU had been added to the sterilized flasks from stock solutions in acetone (10 g liter−1) and the solvent evaporated in a laminar flow bench before the addition of the liquid media. The flasks were placed in the dark at 20°C on an IKA Labortechnik KS 250 Basic Orbital Shaker (Staufen, Germany) at 100 rpm. Mineralization of the IPU was monitored by measuring the production of 14CO2 from added 14C-IPU as described below. Enrichment cultures showing mineralization of 14C-IPU were used to inoculate new flasks by transferring 0.1 ml to 49.9 ml of fresh IPU-containing MS medium. After more than 15 subcultures had been performed, a stable mixed bacterial culture was obtained. Since no IPU-degrading bacteria were obtained from the mixed culture by streaking samples onto various agar media, several successive dilutions (dilution ratio 1:10) were made to reduce the diversity within the mixed culture. 0.1 ml of each dilution were used to inoculate flasks with 49.9 ml of fresh IPU-containing (25 mg liter−1) MS. 14CO2 production was measured for 30 days. Thereafter, the highest dilution able to mineralize 14C-IPU was diluted once again, and the procedure was repeated three times.

Isolation, characterization, and identification.

To isolate pure cultures, aliquots (0.1 ml) were plated on different types of agar (NA, TSA, R2A, WA, and IPU agar). The plates were incubated for up to 1 month at 20°C. Colonies were removed and screened for their ability to degrade IPU in pure culture. After the successive dilutions of the enrichment culture, two strains of bacteria (designated SRS1 and SRS2) were isolated from plates with R2A. Stocks of both bacteria grown in R2B were maintained at −80°C in 40% glycerol. Strain SRS2 were characterized and identified by Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany, by analysis of the cellular fatty acids, partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, and different physiological tests. Alignment of the partial 16S rRNA gene sequence was performed with sequences deposited in the GenBank database (National Center for Biotechnology Information) by using CLUSTAL W, version 1.8 (36). A neighbor-joining method (Neighbor-Joining/UPGMA, version 3.573c) from the PHYLIP software package (11) was used to estimate relatedness.

Preparation of inoculum.

Prior to the pure culture degradation studies with the isolated strain SRS2, plate counts on R2A were correlated with optical density measurements (600 nm) in R2B. The strain was grown in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 ml of R2B incubated on a platform shaker at 150 rpm (20°C). Cells were harvested in the late-exponential-growth phase by centrifugation (10 min, 3,500 × g, 20°C), washed twice in medium, and adjusted to a density of 5 × 108 cells ml−1. Each flask was inoculated with washed cells suspended in 1 ml of mineral medium to provide a final density of 107 cells ml−1.

Degradation and mineralization.

All phenylurea and aniline compounds included in this study were added to sterilized flasks as previously described for IPU in the enrichment studies. The herbicides and their metabolites were measured by using a Hewlett-Packard Series 1050 HPLC System (16): 750-μl aliquots were filtered through a 0.45-μm (pore-size) Titan syringe filter (Scientific Resources, Eatontown, N.J.), and the last 250 μl was collected for analysis. Mineralization of 14C-labeled IPU, MDIPU, and 4IA was measured by trapping the evolved 14CO2 in an alkaline solution. Approximately 40,000 dpm of 14C-labeled compound and 1.25 mg (25 mg liter−1) of unlabeled compound were added to each flask. Then, 49 ml of liquid medium was added, and the flasks were inoculated with 1 ml of the cell suspension. A 5-ml test tube holding 2 ml of 0.5 M NaOH was mounted in the flasks. Upon sampling, the alkaline solution was replaced with fresh solution and the used solution was mixed with 10 ml of Wallac OptiPhase HiSafe 3 scintillation cocktail (Turku, Finland) and counted on a Wallac 1409 liquid scintillation counter. The results were corrected for quenching and background radioactivity. Sterile or uninoculated controls were included in all experiments.

RESULTS

Mineralization of IPU in agricultural soils.

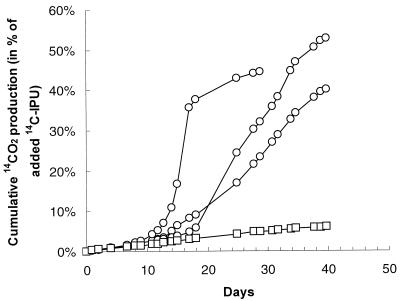

Different IPU mineralization patterns were observed in the two soils studied (Fig. 2) The IPU mineralization rates in slurries of the soil from Græse were constant, and only 6.0% ± 0.5% (n = 3) of the added 14C-IPU was metabolized to 14CO2 within 40 days. In contrast, rapid and accelerated mineralization of IPU was measured in the soil from Deep Slade. The initial degradation rate varied between replicates in the case of the latter soil, but by day 40, 40 to 53% of the 14C-IPU had been metabolized to 14CO2 in all flasks.

FIG. 2.

Mineralization of isoproturon (IPU) in slurries with soils from two different agricultural fields. The data for soil from Deep Slade (○) represent single samples, while those for soil from Græse (□) represent the mean of triplicate samples (the standard deviation is smaller than the symbol).

Enrichment and isolation.

Aliquots of slurries of the soil from Deep Slade exhibiting the fastest mineralization were transferred to fresh IPU-containing MS medium. The mixed IPU-mineralizing cultures obtained were subcultured several times and then diluted serially. After three dilution cycles, aliquots of the highest dilution able to mineralize 14C-IPU were plated onto the R2A, WA, TSA, LB, NA, and IPU agars. Growth of one colony type was seen on R2A and TSA after 2 days of incubation. Based on BIOLOG-GN (Biolog, Hayward, Calif.) profiles, these colonies were determined to be identical and were designated strain SRS1. Between days 5 and 6, another colony with a different morphology appeared on R2A but not on TSA. The strain was designated SRS2. No colonies were observed on WA, LB, NA, or IPU agar after 30 days at 20°C. Only strain SRS2 was able to degrade IPU and, to ensure purity, it was passed from IPU-containing MS to R2A three times.

Characterization and identification of strain SRS2.

Strain SRS2 proved to be a gram-negative non-spore-forming rod with a width of 0.6 to 0.8 μm and a length of 1.5 to 2.5 μm. It is oxidase negative, catalase positive, aminopeptidase positive, and urease negative. It hydrolyzes esculin but not gelatin, DNA, or casein. It is negative in tests for indole production and denitrification. No growth was observed at 42°C after 7 days, and no growth was observed in BIOLOG-GN microplates. Growth on agar was restricted to R2A, where it forms reddish brown colonies within 6 to 7 days at 20°C. The degradative ability of strain SRS2 was very stable and was retained after several generations of nonselective growth on R2A. A whole-cell fatty acid profile revealed that the dominant fatty acids were 53.2% 18:1 (sum of 18:1ω7c, 18:1ω9t, and 18:1ω12t), 20.5% 16:1ω7c and/or 2OH(iso)15:0, 7.2% 2OH14:0, and 6.8% 16:0, which is typical for the genus Sphingomonas (1, 24). Upon comparison of a partial 16S rRNA gene sequence (425 bases) obtained from strain SRS2 with sequences from the GenBank Database, the highest degree of similarity (97%) was obtained with the 16S rRNA gene sequence of a dibenzo-p-dioxin-degrading Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (21, 41). Alignment of the partial 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed a close phylogenetic relationship to several Sphingomonas spp. (data not shown). The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences have been deposited in the GenBank Database under accession no. AJ251638.

Degradation and growth studies with Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2.

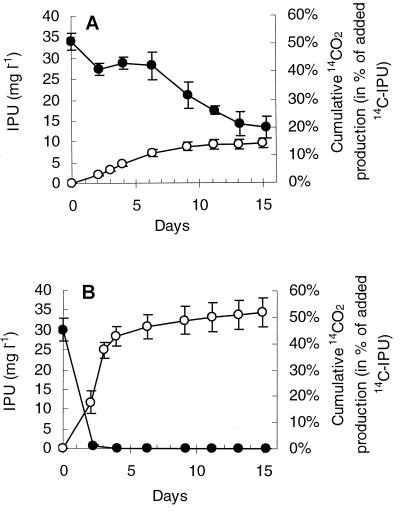

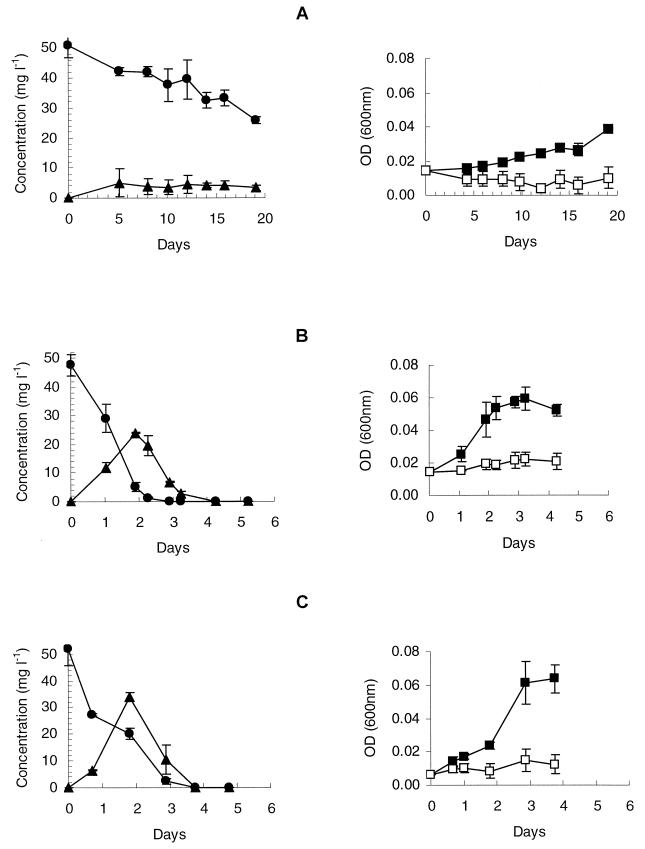

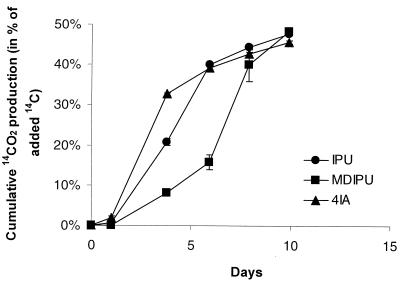

Strain SRS2 mineralized the phenyl structure of IPU slowly (Fig. 3A). Supplementing Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 with Casamino Acids significantly enhanced the degradation activity and resulted in mineralization of ca. 50% 14C-IPU to 14CO2 within 5 days (Fig. 3B). High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis revealed no IPU, metabolites, or unidentified peaks at the end of the experiment (data not shown). Although Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 was able to utilize IPU for growth (Fig. 4A), the growth was slow compared to cultures supplemented with amino acids (Fig. 4B and C). Growth of Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 was not supported on amino acids alone, as shown in controls of MS-CA, MS-A19, and MS-A2 without IPU (Fig. 4B and C and Table 1). Approximately 6.0 × 107 cells SRS2 were produced during degradation of 25 mg of IPU liter−1 (Table 1). Further studies revealed that SRS2 was able to mineralize IPU, MDIPU, and 4IA in MS medium containing l-methionine and glycine (MS-A2) (Fig. 5 and Table 1). HPLC analysis revealed transient accumulation of a main metabolite with the same retention time as MDIPU during the mineralization of IPU (Fig. 4). Trace amounts of metabolites with the same retention times as for DDIPU and 4IA were also detected (data not shown). Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 also mineralized 14C-MDIPU and 14C-4IA (Fig. 5). The mineralization patterns for IPU and the two metabolites revealed that MDIPU was mineralized more slowly than IPU and 4IA, although the amount of 14C-labeled compound metabolized to 14CO2 after 10 days was approximately the same for all three compounds (46 to 49%) (Fig. 5). No phenylurea or aniline compounds were detected at the end of the experiment. Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 was also able to utilize MDIPU, DDIPU, and 4IA for growth in mineral medium supplemented with l-methionine and glycine (MS-A2) (Table 1). Moreover, it was able to degrade diuron and chlorotoluron, both of which contain a dimethylurea side chain like IPU, giving rise to a reddish (chlorotoluron) or brown (diuron) coloration of the medium. No metabolites were detectable by HPLC after dissipation of the parent compound. The coloration of the medium made growth measurements by optical density impossible. No growth of strain SRS2 was observed by plate counts on R2A during degradation of diuron and chlorotoluron, however (Table 1). Linuron, a phenylurea herbicide containing a methoxy-methyl side chain, was not degraded by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2, either. No degradation of any of the compounds included in this study was measured in controls without Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Degradation of isoproturon (IPU) by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 in MS (A) and in MS containing 0.1 g of Casamino Acids liter−1(B). Two parallel sets of flasks were used for measuring the degradation of IPU (●) and the mineralization of 14C-IPU to 14CO2 (○), respectively. The data are mean values (n = 3). The bars indicate the standard deviation.

FIG. 4.

Growth of Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 (▪), growth in controls without isoproturon (IPU) (□), degradation of IPU (●), and production of the metabolite MDIPU (▴) in MS (A), in mineral salt (MS) medium with 0.1 g of Casamino Acids liter−1 (B), and in MS with a defined amino acid mixture (C). The data are mean values (n = 3). The bars indicate the standard deviation.

TABLE 1.

Growth and degradation of phenylurea herbicides and IPU metabolites by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 in 50 ml of MS medium with l-methionine and glycine (MS-A2) after incubation for 10 daysa

| Compound | Degradationb | Cell growth (mean ± SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CFU ml−1c | OD600 | ||

| IPU | + | (6.1 ± 0.9) × 107 | 0.026 ± 0.001 |

| MDIPU | + | (5.8 ± 0.4) × 107 | 0.022 ± 0.001 |

| DDIPU | + | (5.9 ± 0.6) × 107 | 0.022 ± 0.001 |

| 4IA | + | (5.9 ± 0.2) × 107 | 0.025 ± 0.004 |

| Diuron | + | (1.2 ± 0.8) × 106 | Colorede |

| Chlorotoluron | + | (1.2 ± 1.1) × 106 | Colorede |

| Linuron | − | (1.4 ± 1.1) × 106 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| Controld | (1.3 ± 1.0) × 106 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | |

Each compound was provided at 25 mg liter−1. Cell growth is given as the mean optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of duplicates or triplicates (plating) with the standard deviation.

Degradation is based on HPLC results.

Plating on R2A medium.

Controls with MS-A2 and no addition of herbicides or metabolites.

See Results.

FIG. 5.

Mineralization of 14C-isoproturon (14C-IPU) (●) and the IPU metabolites 14C-MDIPU (▪) and 14C-4IA (▴) in MS-A2 by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2. The initial concentration of each compound was 25 mg liter−1. The data are mean values (n = 2). The bars indicate the standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Inoculation of soils from two previously IPU-treated agricultural fields into liquid medium containing 14C-IPU revealed a substantial difference in the ability of the soil microorganisms to mineralize the labeled IPU to 14CO2. Stable enrichment cultures able to rapidly mineralize IPU were obtained from one of the soils (from Deep Slade). In contrast, the mineralization of IPU in slurries containing the other soil (from Græse) was constant, and the activity was lost upon subculturing, indicating the lack of a single microorganism able to proliferate through the mineralization of IPU. We have previously shown that the initial N-demethylation of IPU to MDIPU is a limiting step for accelerated mineralization of IPU in soil from the Græse agricultural field (35), which probably explains the inability to obtain enrichment cultures from this soil. No attempts were made to homogenize the soils and the variation among replicate slurries of the Deep Slade soil may reflect a heterogeneous distribution of IPU-degrading bacteria, as recently demonstrated by Walker et al. (39) in a study of soil from Deep Slade.

A bacterial strain, designated SRS2, able to completely metabolize IPU to CO2 and biomass was isolated from the Deep Slade soil. 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the characteristic cellular fatty acid composition strongly suggested that strain SRS2 belongs to the genus Sphingomonas. Strain SRS2 was phylogenetically related to several previously characterized Sphingomonas spp. able to degrade various aromatic and chloroaromatic compounds (1, 24, 41, 42). That the 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity obtained with the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (41) was no greater than 97% indicates that strain SRS2 is a member of a new species within Sphingomonas. Several previously characterized bacterial strains able to degrade xenobiotic aromatic compounds have recently been reclassified as members of the genus Sphingomonas, and it is becoming evident that Sphingomonas spp. are ubiquitous in the environment and possess broad catabolic capabilities (12, 40). Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 was unable to grow on rich media, thus indicating adaptation to oligotrophic conditions. Other Sphingomonas spp. has been isolated from oligotrophic environments such as river water and seawater (38, 41), bottled mineral water (8), and aquifer sediments (1, 12). This suggests that adaptation to oligotrophic conditions is a characteristic feature of several members of the genus Sphingomonas.

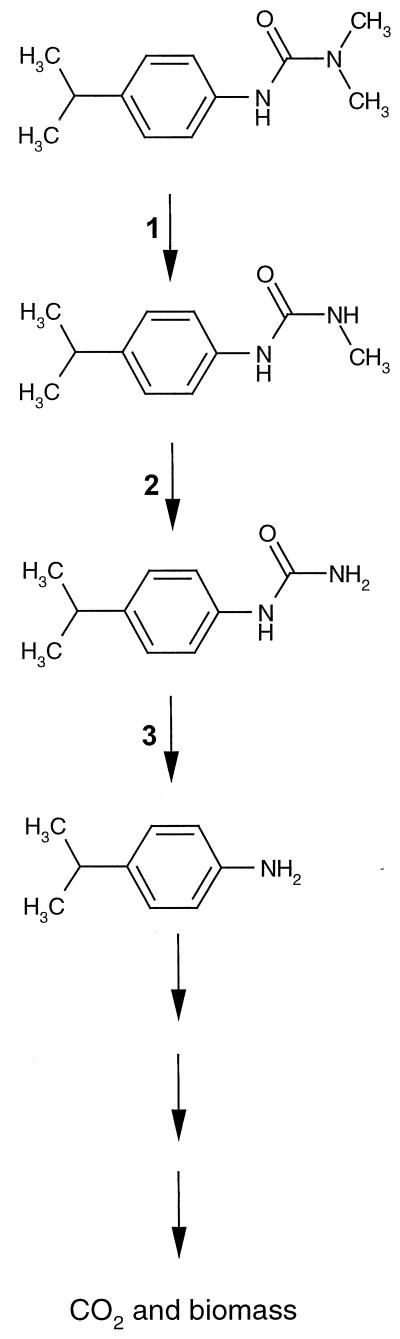

The transient accumulation of MDIPU indicates that the degradation of IPU by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 is initiated by N-demethylation of the dimethylurea side chain (Fig. 6, step 1). MDIPU has previously been reported to be the main metabolite produced during the degradation of IPU in agricultural soils (4, 6, 13, 16, 19, 22). An alternative metabolic pathway involving initial hydroxylation of the isopropyl side chain resulting in 2-hydroxy-IPU [3-(4-(2-hydroxyisopropyl)-phenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea] has also been described in agricultural soils (19, 32). Measurements of both MDIPU and 2-hydroxy-IPU in soil porewater, surface runoff and a nearby creek after IPU treatment of an agricultural field revealed that both pathways are active in the environment (32). Trace amounts of the metabolites DDIPU and 4IA, which have previously been detected in agricultural soils (16, 19, 22, 35), were also detected during the mineralization of IPU by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2. Since strain SRS2 also degraded DDIPU and 4IA, we suggest that the metabolic pathway used by the strain comprises N-demethylation of MDIPU to DDIPU (Fig. 6, step 2), followed by cleavage of the urea side chain to 4IA (Fig. 6, step 3) and mineralization of 4IA to CO2 and production of biomass (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Although microorganisms in agricultural soils are able to mineralize 4IA, the metabolite is rapidly bound, thereby reducing the extent of biodegradation (5, 29). Recently, we described a mixed bacterial culture from the Græse agricultural field that is able to mineralize MDIPU and 4IA (35) but not able to degrade DDIPU. A metabolic pathway involving cleavage of the methylurea group of MDIPU directly to 4IA that differs from the N-demethylation to DDIPU performed by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 may thus be active in the Danish soil. By mineralization we mean conversion of IPU to CO2 and other inorganic species and incorporation into biomass. About 50% of the 14C-IPU was mineralized to 14CO2 during the metabolism of IPU by strain SRS2. Remaining 14C must at least partly have been incorporated into biomass, as indicated by the increase to ca. 6 × 107 cells of strain SRS2 during the degradation of 25 mg of IPU liter−1 (Table 1). However, the presence of unknown 14C-labeled metabolites not detectable by our HPLC method cannot be excluded.

FIG. 6.

Proposed pathway for the metabolism of isoproturon (IPU) by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2. Initial N-demethylation to MDIPU (step 1) is followed by another N-demethylation to DDIPU (step 2), cleavage of the methylurea side chain to 4IA (step 3), and ultimately mineralization of the phenyl structure to CO2 and production of biomass.

An Arthrobacter globiformis strain (designated D47) has recently been isolated from the Deep Slade agricultural field that is able to transform the phenylurea herbicides diuron, linuron, monolinuron, metoxuron, and IPU to their respective aniline derivatives (7). However, no degradation of the aniline metabolites was observed, and the transformation of IPU was slow, with 50% IPU remaining after 28 days at 20°C. A. globiformis D47 transformed IPU by a single step involving hydrolytic cleavage of the dimethylurea side chain to 4IA (37), in contrast to the metabolic pathway proposed for Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2, which involves successive N-demethylation (Fig. 6). Supplementing A. globiformis D47 with glucose and NH4Cl greatly enhanced the transformation of IPU (7), thus indicating a cometabolic process. Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 was able to mineralize IPU, MDIPU, DDIPU, and 4IA. Roberts et al. (31) isolated several bacteria from the Deep Slade agricultural field that are able to degrade IPU to MDIPU and DDIPU by two successive N-demethylation steps. However, the capacity to degrade DDIPU to 4IA (Fig. 6, step 3) and subsequent mineralization of the phenyl structure were not shown. The enrichment and pure culture studies described in that study were conducted in a medium supplemented with ethanol, which also suggests the involvement of cometabolic processes. Since only a few isolates able to degrade phenylurea herbicides have yet been described, knowledge of the enzymes involved in the degradation process is generally lacking. Some studies indicate specificity related to methoxy-methyl-substituted phenylurea herbicides (9, 10). An aryl acylamidase purified from Bacillus sphaericus ATCC 12123 isolated from agricultural soil had specificity related to methoxy-methyl-substituted phenylurea herbicides but no activity toward dimethyl-substituted phenylurea herbicides (10). El-Fantroussi (9) found a similar specificity for degradation of methoxy-methyl-substituted herbicides in a recent study of a bacterial consortium enriched from agricultural soil. In contrast to A. globiformis D47 and B. sphaericus ATCC 12123, further degradation of the aniline metabolites was observed with the consortium, thus suggesting mineralization of the methoxy-methyl-substituted herbicides. The nature of the metabolic pathways in the degradation of dimethylurea-substituted diuron and chlorotoluron by Sphingomonas sp. SRS2 remains to be elucidated and will be the subject of a future study.

The ability to enrich degraders able to mineralize IPU is related to the distribution of the involved metabolic pathways among members of the soil microbial community. Strains harboring the entire pathway could be able to proliferate from the mineralization of IPU, as observed with Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2 isolated from the Deep Slade soil. In strains possessing only part of the metabolic pathway, in contrast, the mineralization rate might be limited by cometabolic or abiotic degradation steps, as previously proposed for the Græse soil (35). In conclusion, the Sphingomonas sp. isolated in the present study harbors the metabolic pathway for the mineralization of IPU. This involves two N-demethylation steps, followed by cleavage of the urea side chain leading to mineralization of the phenyl structure. The ability of the strain to transform diuron and chlorotoluron but not linuron suggests specificity for dimethyl-substituted phenylurea herbicides, although this remains to be clarified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the European Commission Environment and Climate Research Programme (Contract: ENV4-CT97-0441, Climate and Natural Hazards) and a bilateral Danish-Israeli Research Project (FRACFLUX).

We thank Patricia Simpson for skillful technical assistance and Allan Walker (Horticulture Research International, Warwick, United Kingdom) and Ole Stig Jacobsen (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, Denmark) for kindly providing the soil samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balkwill D L, Drake G R, Reeves R H, Fredrickson J K, White D C, Ringelberg D B, Chandler D P, Romine M F, Kennedy D W, Spadoni C M. Taxonomic study of aromatic-degrading bacteria from deep-terrestrial-subsurface sediments and description of Sphingomonas aromaticivorans sp. nov., Sphingomonas subterranea sp. nov., and Sphingomonas stygia sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:191–201. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behera B C, Bhunya S P. Genotoxic effect of isoproturon (herbicide) as revealed by three mammalian in vivo mutagenic bioassays. Ind J Exp Biol. 1990;28:862–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger B M. Parameters influencing biotransformation rates of phenylurea herbicides by soil microorganisms. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1998;60:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger B M. Factors influencing transformation rates and formation of products of phenylurea herbicides in soil. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:3389–3396. doi: 10.1021/jf981285q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bollag J-M, Blattmann P, Laanio T. Adsorption and transformation of four substituted anilines in soil. J Agric Food Chem. 1978;26:1302–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox L, Walker A, Welch S J. Evidence for the accelerated degradation of isoproturon in soils. Pestic Sci. 1996;48:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullington J E, Walker A. Rapid biodegradation of diuron and other phenylurea herbicides by a soil bacterium. Soil Biol Biochem. 1999;31:677–686. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Defives C, Guyard S, Oularé M M, Mary P, Hornez J P. Total counts, culturable and viable, and non-culturable microflora of a French mineral water: a case study. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:1033–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Fantroussi S. Enrichment and molecular characterization of a bacterial culture that degrades methoxy-methyl urea herbicides and their aniline derivatives. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5110–5115. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5110-5115.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelhardt G, Wallnöfer P R, Plapp R. Purification and properties of an aryl acylamidase of Bacillus sphaericus, catalyzing the hydrolysis of various phenylamide herbicides and fungicides. Appl Microbiol. 1973;22:284–288. doi: 10.1128/am.26.5.709-718.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), version 3.5c. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredrickson J K, Balkwill D L, Romine M F, Shi T. Ecology, physiology, and phylogeny of deep subsurface Sphingomonas sp. J Ind Microbiol Biotech. 1999;23:273–283. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaillardon P, Sabar M. Changes in the concentrations of isoproturon and its degradation products in soil and soil solution during incubation at two temperatures. Weed Res. 1994;34:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshiya T, Hasegawa R, Hakoi K, Cui L, Ogiso T, Cabral R, Ito N. Enhancement by nonmutagenic pesticides of GST-P positive hepatic foci development initiated with diethylnitrosamine in the rat. Cancer Lett. 1993;72:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90011-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson A C, Hughes C D, Williams R J, Chilton P J. Potential for aerobic isoproturon biodegradation and sorption in the unsaturated and saturated zones of a chalk aquifer. J Contam Hydrol. 1998;30:281–297. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhler R K, Sørensen S R, Larsen L. Analysing transformation products of herbicide residues in environmental samples. Water Res. 2001;35:1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen G B, Sørensen S R, Aamand J. Mineralization of 2,4-D, mecoprop, isoproturon, and terbuthylazine in a chalk aquifer. Pest Manag Sci. 2001;57:531–536. doi: 10.1002/ps.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen L, Sørensen S R, Aamand J. Mecoprop, isoproturon, and atrazine in and above a sandy aquifer: Vertical distribution of mineralization potential. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:2426–2430. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehr S, Glässgen W E, Sandermann H, Jr, Beese F, Scheunert I. Metabolism of isoproturon in soils originating from different agricultural management systems and in cultures of isolated soil bacteria. Intern J Environ Anal Chem. 1996;65:231–343. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansour M, Feicht E A, Behechti A, Schramm K-W, Kettrup A. Determination photostability of selected agrochemicals in water and soil. Chemosphere. 1999;39:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore E R B, Wittich R-M, Fortnagel P, Timmis K N. 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence characterization and phylogenetic analysis of a dibenzo-p-dioxin-degrading isolate within the new genus Sphingomomas. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1993;17:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mudd P J, Hance R J, Wright S J L. The persistence and metabolism of isoproturon in soil. Weed Res. 1983;23:239–347. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nitchke L, Schussler W. Surface water pollution by herbicides from effluents of wastewater treatment plants. Chemosphere. 1998;36:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(97)00286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nohynek L J, Nurmiaho-Lassila E-L, Suhonen E L, Busse H-J, Mohammadi M, Hantula J, Rainey F, Salkinoja-Salonen M. Description of chlorophenol-degrading Pseudomonas sp. strains KF1T, KF3, and NKF1 as a new species of the genus Sphingomonas, Sphingomonas subarctica sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:1042–1055. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérés F, Florin D, Grollier T, Feurtet-Mazel A, Coste M, Ribeyre F, Ricard M, Boudou A. Effect of the phenylurea herbicide isoproturon on periphytic diatom communities in freshwater indoor microcosms. Environ Poll. 1996;94:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(96)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pieuchot M, Perrin-Ganier C, Portal J-M, Schiavon M. Study on the mineralization and degradation of isoproturon in three soils. Chemosphere. 1996;33:467–478. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reasoner D J, Geldreich E E. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.1.1-7.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remde A, Traunspurger W. A method to assess the toxicity of pollutants on anaerobic microbial degradation activity in sediments. Environ Toxicol Water Qual. 1994;9:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reuter S, Ilim M, Munch J C, Andreux F, Scheunert I. A model for the formation and degradation of bound residues of the herbicide 14C-isoproturon in soil. Chemosphere. 1999;39:627–639. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgway H F, Safarik J, Phipps D, Carl P, Clark D. Identification and catabolic activity of well-derived gasoline-degrading bacteria from a contaminated aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3563–3575. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3565-3575.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts S J, Walker A, Cox L, Welch S J. Isolation of isoproturon-degrading bacteria from treated soil via three different routes. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:309–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuelein J, Glaessgen W E, Hertkorn N, Schroeder P, Jr, Sandermann H, Kettrup A. Detection and identification of the herbicide isoproturon and its metabolites in field samples after a heavy rainfall event. Intern J Environ Anal Chem. 1996;65:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spliid H S, Køppen B. Occurrence of pesticides in Danish shallow groundwater. Chemosphere. 1998;37:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(98)00128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stangroom S J, Collins C D, Lester J N. Sources of organic micropollutants to lowland rivers. Environ Technol. 1998;19:643–666. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sørensen S R, Aamand J. Biodegradation of the phenylurea herbicide isoproturon and its metabolites in agricultural soils. Biodegradation. 2001;12:69–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1011902012131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turnbull G A, Ousley M, Walker A, Shaw E, Morgan J A W. Degradation of substituted phenylurea herbicides by Arthrobacter globiformis D47 and characterization of a plasmid-associated hydrolase gene. puhA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2270–2275. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2270-2275.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vancanneyt M, Schut F, Snauwaert C, Goris J, Swings J, Gottshal J C. Sphingomonas alaskensis sp. nov., a dominant bacterium from a marine oligotrophic environment. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2001;51:73–80. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker A, Jurado-Exposito M, Bending G D, Smith V J R. Spatial variability in the degradation rate of isoproturon in soil. Environ Pollut. 2001;111:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(00)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White D C, Sutton S D, Ringelberg D B. The genus Sphingomonas: physiology and ecology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7:301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittich R-M, Wilkes H, Sinnwell V, Francke W, Fortnagel P. Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1005–1010. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.1005-1010.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zipper C, Nickel K, Angst W, Kohler H-P E. Complete microbial degradation of both enantiomers of the chiral herbicide mecoprop [(RS)-2-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)propionic acid] in an enantioselective manner by Sphingomonas herbicidovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4318–4322. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4318-4322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]