Abstract

ent-16-Oxobeyeran-19-N-methylureido (NC-8) is a recently synthesized derivative of iso-steviol that showed anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) activity by disturbing replication and gene expression of the HBV and by inhibiting the host toll-like receptor 2/nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. To study its pharmacokinetics as a part of the drug development process, a highly sensitive, rapid, and reliable liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) method was developed and validated for determining NC-8 in rat plasma. After protein precipitation extraction, the chromatographic separation of the analyte and internal standard (IS; diclofenac sodium) was performed on a reverse-phase Luna C18 column coupled with a Quattro Ultima triple quadruple mass spectrometer in the multiple-reaction monitoring mode using the transitions, m/z 347.31 → 75.09 for NC-8 and m/z 295.89 → 214.06 for the IS. The lower limit of quantitation was 0.5 ng/mL. The linear scope of the standard curve was between 0.5 and 500 ng/mL. Both the precision (coefficient of variation; %) and accuracy (relative error; %) were within acceptable criteria of <15%. Recoveries ranged from 104% to 113.4%, and the matrix effects (absolute) were nonsignificant (CV ≤ 6%). The validated method was successfully applied to investigate the pharmacokinetics of NC-8 in male Sprague–Dawley rats. The present methodology provides an analytical means to better understand the preliminary pharmacokinetics of NC-8 for investigations on further drug development.

Keywords: Isosteviol derivative, LC-MS/MS, NC-8, Pharmacokinetics

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B is inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV; of the hepadnavirus family) [1] and is a significant global health problem with an estimated exposure of approximately three-quarters of the worlds’ population and the highest prevalence being in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia [2]. HBV infection ranges from acute clinically asymptomatic hepatitis with resultant clearing of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to chronic hepatitis with detectable HBsAg in the serum for more than 6 months. HBV infection can lead to a reduction in liver function and liver cirrhosis. Chronic hepatitis caused by HBV has been linked to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3]. Current treatments for HBV infection involve nucleoside/nucleotide analogs and interferon (IFN). However, these treatments do not eliminate the virus, have low hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance rates, and produce limited inhibition of progression to HCC [4].

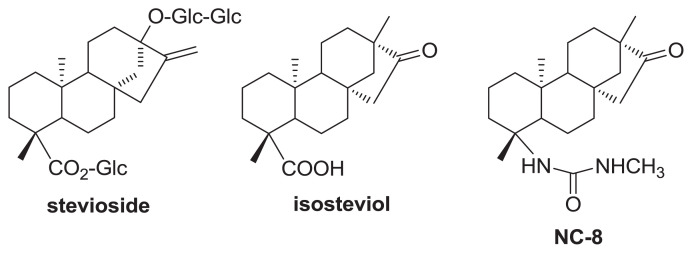

Using naturally occurring molecules as starting points for synthesizing potential drug molecules in drug discovery is well known [5]. Interest in stevioside, a natural sweetener extracted from Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) Bertoni (Compositae) [6], led to the discovery of pharmacological activities of its aglycone derivatives including steviol [7,8], dihydroisosteviol [9,10], and isosteviol [11–13]. Semi-synthesis using isosteviol produced several pharmacologically active derivatives with antiviral [14–16], anti-inflammatory [17,18], cytotoxic [19–21], and α-glucosidase-inhibitory [22] activities. One such derivative, ent-16-oxobeyeran-19-N-methylureido (NC-8; Fig. 1), was shown to be effective against HBsAg and HBeAg secretion in HBV-transfected cell-lines. Its 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50; 7.89 μg/mL) for inhibiting HBsAg secretion was more potent than the reference drug lamivudine (49.13 μg/mL). The anti-HBV activity of NC-8 in Huh7 cells was achieved through inhibition of viral gene expression, reduction of levels of encapsidated viral DNA intermediates, and inhibition of the host cell’s toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)/nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling pathway [15]. This mechanism of action is distinct from that of typical HBV reverse-transcriptase/polymerase inhibitors and other inhibitors that activate the TLR2/NF-κB signaling pathway. It is important to characterize NC-8’s preliminary pharmacokinetic properties for further drug development. Thus, a bioanalytical method development, validation, and application to pharmacokinetic investigations of NC-8 were carried out as an essential part of the drug discovery process. The analysis of pharmacokinetic data by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) offers greater sensitivity and is less time consuming [23,24]; however, the method used in the analysis of bio-samples must be validated in order to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the bioanalytical results. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a bioanalytical method for analyzing NC-8 has been developed.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of stevioside, isosteviol, and NC-8.

2. Methods

2.1. Chemicals and materials

NC-8 (≥97.0% purity) was synthesized from isosteviol (Fig. 1) as described in our previous report [15]. The purity and chemical composition were verified by an elemental analysis using an Elementar Vario EL cube for CHNS (Elementar Analysensystem, Hanau, Germany). The internal standard (IS) used was diclofenac sodium (purity, 99%), which was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). High-performance LC (HPLC)-grade acetonitrile, methanol, and formic acid were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Water was purified by an RDI reverse osmosis/deionizer system (Luton Technic, Taipei, Taiwan). Blank rat plasma was collected in our laboratory from male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats purchased from BioLASCO Taiwan (Taipei, Taiwan).

2.2. Instruments

The LC–MS/MS system consisted of a Waters Alliance 2795 chromatographic system (Milford, MA, USA) and a Quattro Ultima triple quadruple (Milford, MA, USA). The system control and data analysis were performed with Masslynx software, vers. 4.1.

2.3. LC conditions

Chromatographic separation was carried out on a reverse-phase Luna® 5 μm C18(2) 100 Å 50 × 2.0-mm column (Biosil) from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA). The HPLC mobile phase system was isocratic consisting of acetonitrile (55%, phase A), water (35%, phase B), and 0.1% formic acid in water (10%, phase C) at a flow rate of 0.200 mL/min. The sample injection volume was 50 μL.

2.4. MS conditions

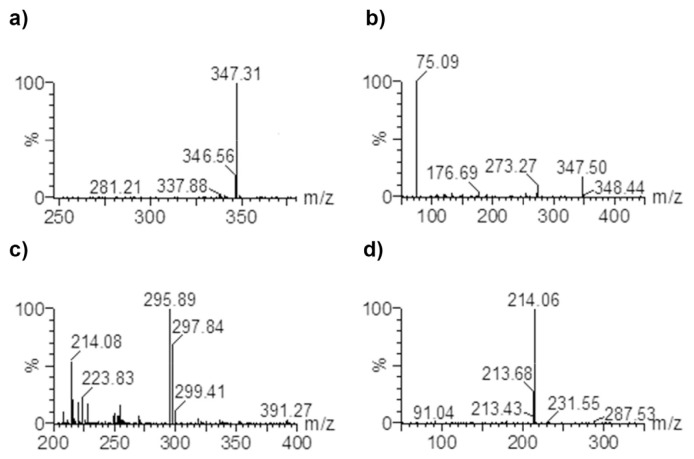

The mass spectrometer was operated with electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive ion mode. The MS/MS spectra of NC-8 produced one fragment at m/z 75.09 while the MS/MS spectra of diclofenac sodium (IS) produced several fragments (m/z 249.67, 214.06, 148.87, and 69.04). However, one fragment at m/z 214.06, a diagnostic fragment for diclofenac [25], was abundant enough for detection. Based on the MS/MS spectra of both analyte and IS producing single abundant fragment ions, the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions were performed at m/z 347.31 → 75.09 for NC-8 and m/z 295.89→214.06 for the IS (Fig. 2). The electrospray parameters used were an electrospray capillary voltage of 3.20 kV, a source temperature of 80 °C, and a desolvation temperature of 400 °C. The cone and desolvation gas flows were 54 and 534 L/h, respectively. The cone voltage was 15 V. The collision potential was 20 V, while the entrance and exit potentials were −1 and 2 V, respectively. The multiplier voltage was set to 750 V.

Fig. 2.

Parent and daughter mass spectra for NC-8 (a and b) and for internal standard (c and d).

2.5. Standard solutions, calibration, and quality control samples

Stock solutions at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL were prepared by separately dissolving 10 mg of NC-8 and 10 mg of IS in 10 mL of methanol. Standard working solutions were then prepared by serial dilution of stock solutions with 100% acetonitrile to obtain working solutions with concentrations of 0.05, 0.5, 5, and 50 ng/μL.

Calibration standards were prepared by spiking 50 μL of blank rat plasma with a freshly prepared working solution at concentrations of 0.05, 0.5, and 5 ng/μL to achieve standards with concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 ng/mL.

Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by spiking 50 μL of blank rat plasma with freshly prepared working solutions of 0.05, 0.5, 5, and 50 ng/μL to obtain the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ), low quality control (LQC), medium quality control (MQC), high quality control (HQC), and two-(2× DQC), five- (5× DQC), and ten-fold-diluted quality control (10× DQC) with nominal concentrations of 0.5, 1.5, 40, 400, 800, 2000, and 4000 ng/mL.

2.6. Sample preparation

Rat plasma samples (50 μL) were placed in a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube, 200 μL of de-protein solvent (0.05 μg/μL diclofenac sodium in 100% acetonitrile) was added, and the mixture was vortexed. Samples were left to stand at room temperature for 1 h [26] and then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. After centrifugation, 200 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a clean test tube and evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream at 25 °C for approximately 12 min. The residue was reconstituted with 100 μL of 40% acetonitrile in water, and left to stand for 15 min at room temperature before being centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was then transferred to a 96-well auto-sampler vial plate from where 50 μL was injected into the LC–MS/MS system.

2.7. Method validation

The LC–MS/MS method was validated in accordance with guidelines for Bioanalytical Method Validation published by the US-Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) Guidelines on Bioanalytical Method Validation with respect to the selectivity, linearity, precision and accuracy, recovery and matrix effects, stability, and dilution [27–29].

2.8. Selectivity

The selectivity of the method was assessed by comparing chromatogram responses of six lots of blank rat plasma with LLOQ and IS-spiked blank plasma.

2.9. Calibration curve and the LLOQ

Calibration standards were prepared by spiking working standard solutions and the IS into 0.05 μL of blank rat plasma. Using data from preliminary studies, a calibration curve was constructed which had a linear range of 0.5–500 ng/mL. Calibration curves were prepared for each analytical run by plotting the back-calculated concentration against the nominal concentration. The linearity assessed by a linear regression using appropriate weighting. The LLOQ was determined to be acceptable after five replicates of the lowest calibration standard showed accuracy and precision deviations of <20%.

2.10. Accuracy and precision

The intra- and inter-assay accuracy and precision were evaluated with six replicates at seven QC levels on a single assay and five assays on three consecutive validation days.

2.11. Recovery

Recovery was determined by comparing the peak areas of extracted LQC, MQC and HQC (1.5, 40 and 400 ng/mL) with post-extraction spiked samples. The recovery percent of analyte and IS were calculated by dividing standard peak areas of the analyte and IS obtained from the extracted samples with those of post-extraction spiked samples.

2.12. Matrix effect

The matrix effect of rat plasma on the NC-8 analysis was determined by comparing peak areas of the analytes in extracted blank plasma to those obtained from clean standard solutions at the corresponding concentrations. The matrix effect was studied at three QC levels in three replicates.

2.13. Stability

The stability of NC-8 in rat plasma was investigated under four different conditions as follows: short-term (8 h of exposure at room temperature), post-preparatively (24 h in an auto-sampler at room temperature), freeze and thaw (three cycles at −80 °C and room temperature), and long-term (−80 °C for 101 days). A bioanalysis of the stability of samples was done with three replicates of QC samples at two QC levels except for the post-preparative study for which three QC levels were used.

2.14. Dilution integrity

The dilution integrity of samples was tested on six replicates of three levels of dilution; two- (2× DQC), five- (5× DQC), and ten-fold (10× DQC) dilutions of the high QC concentration. The calculated concentration measurements were compared to the nominal concentration at each dilution level.

2.15. Pharmacokinetic study

The pharmacokinetic study was carried out on male SD rats that weighed 304 ± 21 g and were kept in a controlled environment at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C and relative humidity of 50% ± 10% for 1 week before the experiments. Standard laboratory food and water were given to rats with the exception of 12 h (overnight) starvation before the experiment, when only water was accessible.

NC-8 was dissolved in a polyethylene glycol 200: dimethyacetamide:dimethysulfoximide (75:35:40, v/v) solvent system for intravenous (jugular vein) administration and 100% polyethylene glycol for oral administration. The solutions for dosing were freshly prepared on the day of administration. For the pharmacokinetic study, two groups (intravenous and oral administration) of six rats each were dosed with 2 mg/kg of NC-8. Approximately 250 μL of blood was collected from the lateral tail vein of each rat using heparinized 1-mL syringes at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 360, 480, 600, and 720 min for both intravenous and oral administration. Blood samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min within 1 h of collection, and plasma layers were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

2.16. Pharmacokinetic data analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined by a non-compartmental analysis and the area under the plasma concentration time curve (AUC) was calculated using a log-linear trapezoid method. The bioavailability (F) was calculated as F = (AUC0–∞ (oral)/AUC0–∞ (IV)) × 100. Pharmacokinetic data were analyzed using PKSolver software vers. 2.0.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optimization of LC–MS/MS conditions

Optimum LC–MS/MS conditions that produced good symmetrical peaks and resolution were achieved after repeated trials. During the development stage, different combinations of the mobile phase and chromatography columns were tried in order to attain optimal chromatographic separation and mobile phase conditions. The mobile phase was initiated at 80% acetonitrile and was later optimized to 55% acetonitrile, 35% water and 10% formic acid (0.1%) to produced better resolution and symmetry of peaks with optimal retention times between 3 and 4 min in reverse-phase chromatography. The mobile phase flow was isocratic with a flow rate optimized to 0.200 mL. The injection solvent was optimized to 40% acetonitrile in water which produced no fronting and splitting of peaks seen with higher acetonitrile percentage.

The ESI positive ion mode resulted in lower noise background and better signal intensities for both analyte and IS than negative ion mode. In mass spectra, the molecular ions at m/z 347.31 [M + H]+ for NC-8 and m/z 295.89 [M]+• for diclofenac were dominant. The MRM transitions m/z 347.31 → 75.09 (NC-8) and m/z 295.89 → 214.06 (IS) which had the most abundant and stable daughter ions were used in quantification.

The mass parameters were fine-tuned for maximum sensitivity, and parent ion transitions were selected to afford the best response for the spectrum analysis. The method was validated using these optimized conditions as described in “Methods”.

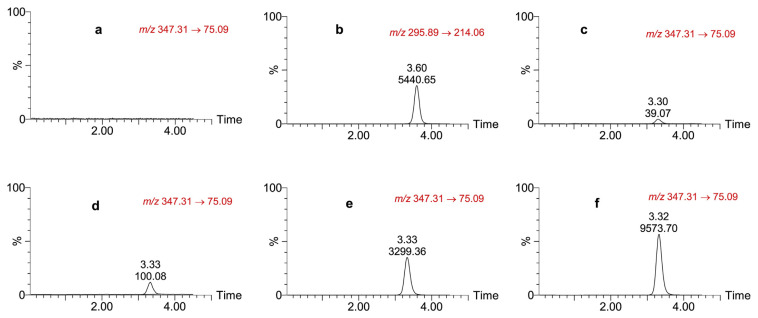

3.2. Selectivity

Fig. 3 shows chromatograms of the blank matrix and those spiked with LLOQ, IS, LQC, MQC, and a plasma sample from a rat taken 30 min after intravenous administration of a 2 mg/kg dose. The method was selective and sensitive enough to enable efficient extraction, and the retention times for detection NC-8 and IS without interference from plasma matrix components were 3.3 and 3.6 min, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Chromatograms of (a) blank rat plasma; (b) the internal standard; (c) lower-limit of quantitation; (d) low quality control; (e) medium quality control, and (f) rat plasma concentration, 60 min after intravenous administration of a 2 mg/kg dose of NC-8.

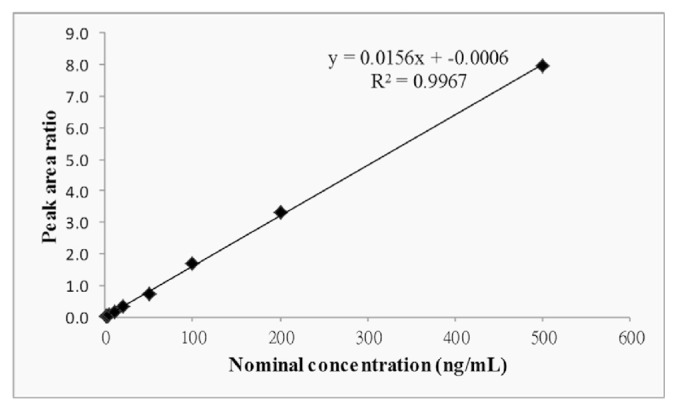

3.3. Calibration curve and LLOQ

The calibration curve linearity was evaluated five times on three different occasions. The linear range for the NC-8 calibration curve was 0.5–500 ng/mL, and the best fit was indicated by a correlation coefficient of ≥0.9967. A linear regression was used to produce the best fit for the analyte concentration-detector response relationship using 1/x2 least square weighting (Fig. 4). The LLOQ was 0.5 ng/mL. Deviations of back-calculated concentrations for all calibration curve points and the LLOQ from the nominal were <15% and 20%, respectively. The correlation coefficient for the calibration curve was comparable to that reported for isosteviol by Jin et al. [30] and Bazargan et al. [31], while their LLOQs were 50 ng/mL and 5 μg/mL respectively, which were higher than 0.5 ng/mL.

Fig. 4.

Calibration curve for NC-8 in rat plasma (n = 5).

3.4. Accuracy and precision

The accuracy and precision were determined at the LLOQ, LQC, MQC, HQC of 0.5, 1.5, and 40, 400 ng/mL, respectively, and three dilution levels of 2× DQC, 5× DQC, and 10× DQC at 800, 2000, and 4000 ng/mL, respectively. Results are shown in Table 1. The intra-assay coefficients of variation ranged between 1.6% and 9.7%, and the percent relative errors range was −10.3% to 3.1%. Inter-assay ranges were 7.3%–12.9% for the CVs and −5.2% to 5.0% for relative errors (REs). The accuracy and precision of NC-8 in this study were similar to those of isosteviol reported by Bazargan et al. [31], while less variation was seen by Jin et al. [30]. Nevertheless, the accuracy and precision CVs were within acceptable ranges. The accuracy and precision of the method for determining NC-8 were within acceptable ranges according to US-FDA and the EMA guidelines, indicating the suitability and reproducibility of the analytical method within the specified concentration range.

Table 1.

Intra-assay and inter-assay accuracy and precision of NC-8 in plasma (n = 6).

| Nominal concentration (ng/mL) | Observed concentration ± SD (ng/mL) | Precision (CV%) | Accuracy (RE%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-assay | 0.5 | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 9.7 | 1.0 |

| 1.5 | 1.49 ± 0.08 | 5.6 | −0.8 | |

| 40 | 35.90 ± 1.12 | 3.1 | −10.3 | |

| 400 | 395.25 ± 6.51 | 1.6 | −1.2 | |

| 800 | 824.91 ± 27.87 | 3.4 | 3.1 | |

| 2000 | 2004.66 ± 48.58 | 2.4 | 0.2 | |

| 4000 | 4063.67 ± 122.20 | 3.0 | 1.6 | |

| Inter-assay | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 12.9 | −3.0 |

| 1.5 | 1.54 ± 0.14 | 8.9 | 2.6 | |

| 40 | 37.94 ± 3.48 | 9.2 | −5.2 | |

| 400 | 410.72 ± 31.90 | 7.8 | 2.7 | |

| 800 | 839.86 ± 68.45 | 8.2 | 5.0 | |

| 2000 | 2048.61 ± 148.95 | 7.3 | 2.4 | |

| 4000 | 4197.88 ± 335.97 | 8.0 | 4.9 |

SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; RE, relative error.

3.5. Recovery and matrix effect

Respective recoveries for QC levels of 1.5, 40, and 400 ng/mL were 112.1%, 104.0%, and 113.2%, with all CVs of <5%. Respective matrix effects for QC levels of 1.5 and 400 ng/mL were 95.24% and 100.30%, with CVs of <7% (Table 2). The recoveries in this study for NC-8 were much higher than those reported for isosteviol by Jin et al. [30], which ranged from 60% to 76%, with CVs of ≤7.3%. Compared to NC-8 in this study, larger effects of plasma matrix were also seen with the isosteviol elution time in the study by Jin et al. [30]. The CVs of < 15% indicate that the method produced very good and reproducible recovery of NC-8 from rat plasma after extraction and that the effect of the rat plasma matrix on the bio-analytical method of NC-8 was not significant (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Assessment of the recovery and matrix effect of NC-8 in rat plasma.

| Compound | Nominal concentration (ng/mL) | Recovery (%, n = 18) | CV (%) | Matrix effect (%, n = 18) | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-8 | 1.5 | 112.1 | 4.5 | 95.24 | 4.00 |

| 40 | 104.0 | 3.7 | |||

| 400 | 113.2 | 2.2 | 100.30 | 6.85 | |

| Diclofenac sodium (IS) | 0.02 | 98.88 | 5.10 | ||

| 0.02 | 39.1 | 13.6 | 99.61 | 3.12 |

CV, coefficient of variation; IS, internal standard.

3.6. Stability

NC-8 was evaluated for short-term stability, freeze/thaw stability, post-preparative stability and long-term stability in three replicates at two levels of QC. Results are shown in Table 3. Long-term stability indicated that NC-8 was stable for 101 days in plasma at −80 °C. The CV and RE values for all stability conditions tested were <12% (Table 3). In a method development and validation study of isosteviol, Jin et al. found stability CVs of ≤5% but the long-term stability of isosteviol was 61 days [30]. That was shorter than what was found in this study. The results indicated that NC-8 was stable under all conditions expected to be experienced using this bioanalytical method.

Table 3.

Stability of NC-8 in rat plasma.

| Stability test | Nominal concentration (ng/mL) | Calculated concentration (ng/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean ± SD | CV (%) | RE (%) | ||

| Short-term (8 h, RT) | 1.5 | 1.38 ± 0.09 | 6.6 | −8.0 |

| 400 | 371.21 ± 13.32 | 3.6 | −7.2 | |

| Freeze and thaw (−80 °C to RT) | 1.5 | 1.47 ± 0.13 | 8.9 | −2.0 |

| 400 | 403.34 ± 5.15 | 1.3 | 0.8 | |

| Post-preparative (24 h, RT) | 1.5 | 1.61 ± 0.15 | 9.1 | 7.1 |

| 40 | 44.10 ± 0.59 | 1.3 | 10.2 | |

| 400 | 445.40 ± 27.28 | 6.1 | 11.4 | |

| (24 h, 4 °C) | 1.5 | 1.46 ± 0.04 | 2.5 | −2.7 |

| 40 | 39.67 ± 0.45 | 1.1 | −0.8 | |

| 400 | 444.56 ± 5.40 | 1.2 | 11.1 | |

| Long-term (101 days, −80 °C) | 1.5 | 1.46 ± 0.17 | 11.6 | −2.4 |

| 400 | 402.35 ± 18.97 | 4.7 | 0.6 | |

SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; RE, relative error; RT, room temperature.

3.7. Dilution

Dilution integrity was tested on six replicates of two- (2× DQC), five- (5× DQC), and ten-fold (10× DQC) dilutions. The accuracy and precision of all diluted QC levels were all within the acceptable criteria with CVs of 3.4%, 2.4%, and 3.0%, and REs of 3.1%, 0.2%, and 1.6%, respectively, for intra-assay accuracy and precision. The inter-assay precision and accuracy showed CVs of 8.2%, 7.3%, and 8.0%, and REs of 5.0%, 2.4% and 4.9%, respectively (Table 1). Similar dilution accuracies and precisions were reported for the related compound, isosteviol, albeit with CVs of ≤3.6% [30]. The results show that the method is accurate, precise, and reproducible in assays of diluted samples with NC-8 concentrations of >400 ng/mL as indicated by CVs and REs of <15% as per US-FDA and EMA guidelines.

3.8. Pharmacokinetic application

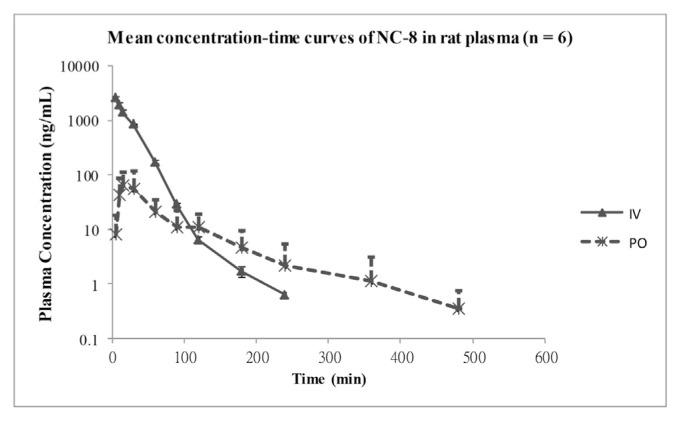

The method was used to determine the pharmacokinetics of NC-8 in male SD rats after IV and oral administration of a 2 mg/kg dose. Concentration time profiles (n = 6) are shown in Fig. 5. The non-compartmental analysis parameters are given in Table 4. A rapid rise in the plasma concentration was seen after oral dosing with a Tmax of 19.17 min, and the elimination half-life (t1/2) for oral dose being almost double that of the IV dose at 77.62 min suggesting possible absorption rate-limited elimination. Oral dosing showed increased clearance, and the apparent volume of the distribution during the terminal phase (Vz) was higher with oral dosing at 83.25 L compared to IV at 1.59 L, while the steady-state volume of the distribution (Vss) was 0.63 ± 0.08 L. The MRT was approximately five times longer (101.05 min) in oral administration. The bioavailability was low at 6.53%.

Fig. 5.

Mean plasma concentration–time curves of NC-8 in rats after intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of a 2 mg/kg dose. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 6).

Table 4.

Non-compartmental model parameters of NC-8 after intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of a 2 mg/kg dose (mean ± SD, n = 6).

| Pharmacokinetic parameters | 2 mg/kg of NC-8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Unit | IV | PO | |

| Cmax | ng mL−1 | – | 71.43 ± 62.30 |

| C0 | ng mL−1 | 3318.09 ± 427.83 | – |

| Tmax | min | – | 19.17 ± 8.61 |

| t½ | min | 35.46 ± 7.94 | 77.62 ± 24.13 |

| AUC0–t | ng min mL−1 | 65,183.33 ± 4273.56 | 4255.62 ± 3120.48 |

| AUC0–∞ | ng min mL−1 | 65,223.31 ± 4269.80 | 4371.62 ± 3084.81 |

| MRT0–∞ | min | 20.63 ± 1.12 | 101.05 ± 30.38 |

| Vz or Vz/F | L | 1.59 ± 0.45 | 83.25 ± 69.97 |

| Cl or Cl/F | L min−1 | 0.031 ± 0.0021 | 0.697 ± 0.45 |

| Vss | L | 0.63 ± 0.032 | – |

Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; C0, concentration at time zero; Tmax, time to achieve maximum plasma concentration; t½, terminal half-life; AUC0–t, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from zero to last observation time; AUC0–∞, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to extrapolated infinity; MRT0–∞, the mean residence time from zero to infinity; Vz, the terminal volume of distribution; Cl, plasma clearance; Vss, steady state volume of distribution.

4. Conclusions

The method presented in this paper was developed to facilitate the pharmacokinetic study of NC-8 in rats, as part of the preclinical drug-development process in search of novel anti-hepatitis B agents. This LC–MS/MS bioanalytical method which was validated according to international guidelines showed extremely good selectivity with very minimal matrix effects and very good linearity, accuracy, precision, recovery, and stability. The dilution integrity was also very good allowing for the analysis of samples with nominal concentrations of >400 ng/mL. Worth noting are the very good recoveries of almost 100% at both high and low concentrations and the extensive stability of NC-8 in rat plasma at −80 °C for 101 days. In addition, the limit of quantitation in this method was much lower than those reported for isosteviol but allowed for detection of NC-8 at 4 and 8 h after single dose intravenous and oral administration, respectively. The method uses a minimal plasma sample of 50 μL which was prepared by a protein precipitation method and has short retention times of <4 min ensuring a relatively short analysis time. This method was reliably applied in the study of the pharmacokinetics of a single orally and intravenously administered 2 mg/kg dose of NC-8 in rat plasma. It is the first bioanalytical method using LC–MS/MS to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of NC-8. Hence, this analytical method could be useful in the preclinical pharmacokinetic study of NC-8 and related diterpenoid compounds as a part of drug-development processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Chih-Hung Fan and Mr. Chin-Yu Shih for the valuable technical support they offered during this research. Financial support from Rosetta Pharmamate Co., Ltd, Taipei, Taiwan is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Statement

Financial support from Rosetta Pharmamate Co., Ltd, Taipei, Taiwan is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:S13–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.22881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Word Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. 2015 March; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gomaa AI, Waked I. Recent advances in multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:673–87. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lok AS. Personalized treatment of hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:1–6. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.21.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lahlou M. The success of natural products in drug discovery. Pharmacol Pharm. 2013;4:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ceunen S, Geuns JM. Steviol glycosides: chemical diversity, metabolism, and function. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1201–28. doi: 10.1021/np400203b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boonkaewwan C, Burodom A. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of stevioside and steviol on colonic epithelial cells. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93:3820–5. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rizzo B, Zambonin L, Angeloni C, Leoncini E, Dalla Sega FV, Prata C, et al. Steviol glycosides modulate glucose transport in different cell types. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;348169 doi: 10.1155/2013/348169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dorfman RI, Nes WR. Anti-androgenic activity of dihydroisosteviol. Endocrinology. 1960;67:282–5. doi: 10.1210/endo-67-2-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pariwat P, Homvisasevongsa S, Muanprasat C, Chatsudthipong V. A natural plant-derived dihydroisosteviol prevents cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2008;324:798–805. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu D, Zhang S, Foster DJ, Wang J. The effects of isosteviol against myocardium injury induced by ischaemia-reperfusion in the isolated Guinea pig heart. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:488–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen X, Hermansen K, Xiao J, Bystrup SK, O’Driscoll L, Jeppesen PB. Isosteviol has beneficial effects on palmitate-induced alpha-cell dysfunction and gene expression. PLoS One. 2012;7e:34361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu D, Xu M, Lin L, Rao S, Wang J, Davey AK. The effect of isosteviol on hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia induced by lipotoxicity in rats fed with high-fat emulsion. Life Sci. 2012;90:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akihisa T, Hamasaki Y, Tokuda H, Ukiya M, Kimura Y, Nishino H. Microbial transformation of isosteviol and inhibitory effects on Epstein-Barr virus activation of the transformation products. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:407–10. doi: 10.1021/np030393q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang TJ, Chou BH, Lin CW, Weng JH, Chou CH, Yang LM, et al. Synthesis and antiviral effects of isosteviol-derived analogues against the hepatitis B virus. Phytochemistry. 2014;99:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang TJ, Yang CL, Kuo YC, Chang YC, Yang LM, Chou BH, et al. Synthesis and anti-hepatitis B virus activity of C4 amide-substituted isosteviol derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:720–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chang SF, Chou BH, Yang LM, Hsu FL, Lin WK, Ho Y, et al. Microbial transformation of isosteviol oxime and the inhibitory effects on NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:6348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chou BH, Yang LM, Chang SF, Hsu FL, Wang LH, Lin WK, et al. Transformation of isosteviol lactam by fungi and the suppressive effects of its transformed products on LPS-induced iNOS expression in macrophages. J Nat Prod. 2011;74:1379–85. doi: 10.1021/np100915q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu Y, Dai GF, Yang JH, Zhang YX, Zhu Y, Tao JC. Stereoselective synthesis of 15- and 16-substituted isosteviol derivatives and their cytotoxic activities. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:1818–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang T, Lu LH, Liu H, Wang JW, Wang RX, Zhang YX, et al. D-ring modified novel isosteviol derivatives: design, synthesis and cytotoxic activity evaluation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;19:5827–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ukiya M, Sawada S, Kikuchi T, Kushi Y, Fukatsu M, Akihisa T. Cytotoxic and apoptosis-inducing activities of steviol and isosteviol derivatives against human cancer cell lines. Chem Biodivers. 2013;10:177–88. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu Y, Yang JH, Dai GF, Liu CJ, Tian GQ, Ma WY, et al. Stereoselective synthesis of bioactive isosteviol derivatives as alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:1464–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen YA, Hsu KY. Development of a LC-MS/MS-based method for determining metolazone concentrations in human plasma: application to a pharmacokinetic study. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21:154–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engida AM, Faika S, Nguyen-Thi BT, Ju YH. Analysis of major antioxidants from extracts of Myrmecodia pendans by UV/visible spectrophotometer, liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, and high-performance liquid chromatography/UV techniques. J Food Drug Anal. 2015;23:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kosjek T, Heath E, Pérez S, Petrovć M, Barceló D. Metabolism studies of diclofenac and clofibric acid in activated sludge bioreactors using liquid chromatography with quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Hydrol. 2009;372:109–17. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wani TA, Zargar S. New ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the determination of irbesartan in human plasma. J Food Drug Anal. 2015;23:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pandey S, Pandey P, Tiwari G, Tiwari R. Bioanalysis in drug discovery and development. Pharm Methods. 2010;1:14–24. doi: 10.4103/2229-4708.72223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on bioanalytical method validation. 2011. [Accessed 5 April 2015]. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2011/08/WC500109686.pdf.

- 29.Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry, bioanalytical methods validation. 2013. [Accessed 13 January 2015]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm368107.pdf.

- 30. Jin H, Gerber JP, Wang J, Ji M, Davey AK. Oral and i.v. pharmacokinetics of isosteviol in rats as assessed by a new sensitive LC-MS/MS method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;48:986–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bazargan M, Gerber JP, Wang J, Chitsaz M, Milne RW, Evans AM. Determination of isosteviol by LC-MS/MS and its application for evaluation of pharmacokinetics of isosteviol in rat. DARU. 2007;15:146–50. [Google Scholar]