Abstract

The comparative analysis of the fatty acid composition of Cassia tora (leaves and stem) was determined using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Twenty-seven fatty acids were identified in C. tora (leaves and stem) which was collected from three different geographical areas of India: Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh), Nainital (Uttarakhand), and Bhavnagar (Gujarat), coded as CT-1, CT-2, and CT-3, respectively. The gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis showed the presence of various saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. The major fatty acids found were palmitic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, margaric acid, melissic acid, and behenic acid. The highest amounts of saturated fatty acids were found in leaves of C. tora collected from Bhavnagar (Gujarat) (60.7% ± 0.5%). Thus, the study reveals that C. tora has a major amount of nutritionally important fatty acids, along with significant antimicrobial potential. Fatty acids play a significant role in the development of fat products with enhanced nutritional value and clinical application. Remarkable differences were found in the present study between fatty acid profiles of C. tora collected from different locations in India. To the best of our knowledge there is no previously reported comparative study of the fatty acids of C. tora.

Keywords: antibacterial activity Cassia tora fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) Gas chromatography, mass spectrometry

1. Introduction

Lipids are considered one of the most elemental nutrients for humans. Lipids consist of fatty acids, classified mostly according to the presence or absence of double bonds: saturated (without double bonds), monounsaturated (with one double bond), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (with two or up to six double bonds) [1]. These fatty acids are widely occurring in natural fats and dietary oils, and they play an important role as nutritious substances and metabolites in living organisms [2]. Many fatty acids, such as lauric, palmitic, linolenic, linoleic, oleic, stearic, and myristic acids are known to have antibacterial and antifungal properties [3,4]. Recent studies have also clearly shown the important impact of fatty acids on human health, particularly in the prevention of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and cancer. They also play a role in the prevention of inflammatory, thrombotic, and autoimmune disease, hypertension, diabetes type two, renal diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease [5,6]. Cassia tora is a legume in the subfamily Caesalpinioideae. It grows wild in most of the tropics and is considered a weed in many places; its native range is not well known, but is probably South Asia. Some previous studies has been reported that the physio-chemical and fatty acid content of C. tora seed oil have shown good antibacterial potential. To the best of our knowledge none of the studies has been reported the comparative analysis of fatty acid composition and its antibacterial activity in C. tora plant.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the fatty acid composition and its antibacterial potential in one of the most popularly known tropical plants, C. tora, for two parts of the plant (leaves and stem), collected from three different locations in India. Our study undoubtedly confirms that the leaves and stem of C. tora contain a relatively high percentage of fatty acids, with antibacterial potential for clinical application, which would enhance its economic status.

2. Methods

2.1. Plant material

C. tora plants were collected from three different locations in India: Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh), Nainital (Uttarakhand), and Bhavnagar (Gujarat), coded as CT-1, CT-2, and CT-3, respectively. The plant materials were authenticated at the Herbarium of the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR), India, National Botanical Research Institute, Lucknow, where voucher specimens are deposited. The fresh leaves and stems were collected, washed thoroughly, and dried in shade.

2.2. Soxhlet extraction

The powdered leaves (15 g) and stem (15 g) were extracted with 300 mL of petroleum ether (40–60°C) in a soxhlet extractor (Borosil, Lucknow) for 10 hours. The extract was cooled to room temperature and evaporated under reduced pressure at 40°C, stored in dark bottles, and kept at 4°C for further analysis.

2.3. Formation of fatty acid methyl ester

The crude extract (500 mg) in concentrated sulphuric acid (2 mL) and methanol (20 mL) was heated under reflux on a water bath for 3 h. It was cooled to room temperature and extracted with petroleum ether (3 × 20 mL) and water in a separating funnel. The petroleum ether extract was dried over Na2SO4. The extract was dried under reduced pressure at 40°C. Prepared fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) was stored for further analysis.

2.4. Gas chromatography

Gas Chromatography was accomplished with a Thermo Fisher TRACE GC ULTRA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bangalore) using a TR 50MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm, film thickness); carrier gas, helium; temperature programming, 2 min delay for solvent, at 50°C temperature rising at 2°C/min to 120°C and at 3°C/min to 250°C and finally held isothermally for 15 min. The injector temperature was 230°C and carrier flow was constant at 1 mL/min, in split mode (1:50) with injector volume 1 μL. The relative proportion of the sample constituents were percentages obtained (% area) using flame ionization detector peak-area normalization, without the use of response factor.

2.5. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis was performed with a Thermo Fisher TRACE GC ULTRA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bangalore) coupled with DSQ II Mass Spectrometer instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bangalore) using a TR 50MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm, film thickness); carrier gas, helium; temperature programming, 5 min delay for solvent, at 50°C temperature, hold time 5.0 min, rising at 4°C/min to 250°C and finally held isothermally for 5 min. The injector temperature was 230°C and carrier flow was constant at 1 mL/min, in split mode (1:50) with injector volume 1 μL. The ion source temperature was set at 220°C, transfer line temperature was 300°C, and the ionization of the sample components was performed in electron ionization mode at an ionization voltage of 70eV. Mass range was used from m/z 50 to 650 amu.

2.6. Compound identification

Identification of individual compounds was made by comparison of their mass spectra with those of the internal reference mass spectra library (NIST/Wiley) or with authentic compounds [7].

2.7. Antibacterial activity

2.7.1. Minimal inhibitory concentration determination

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were used for in vitro antibacterial activities using the broth microdilution method as described previously, with some minor modifications [8]. Briefly, all wells of a sterilized flat 96-well microplate were filled with 100 μL of sterile Mueller Hinton Broth. All extracts (FAME) of C. tora was first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (0.5%) and then reduced with a serial twofold dilution. For each well, suspension of logarithmic phase bacterial culture with turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard [9] was inoculated. Each antibacterial test also included wells containing the culture media plus dimethyl sulfoxide (0.5%) in order to obtain a control sample of the solvent antibacterial effect, and ampicillin was used as the positive control of bacterial growth inhibition. Microplates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The minimal inhibitory concentration value was defined as the lowest concentration producing no visible growth (absence of turbidity and/or precipitation) as observed through the naked eye. For further confirmation, 20 μL (1 mg/mL) of 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide reagent was added to the selected wells, followed by aerobic incubation at 37°C for 25 min. A clear/yellowish color of the reagent suspension shows killing activity, whereas dark blue indicates growth [10].

3. Results

3.1. Fatty acid analysis

The fatty acid composition of C. tora (leaves and stem) is summarized in Lucknow 1. Twenty seven fatty acids were identified in the extract of C. tora (CT-1,2,3) leaves and stem in petroleum ether: CT-1 leaves (CT-1L; 82.6% ± 0.06%), CT-1 stem (CT-1S; 78.9% ± 0.15%), CT-2L (58.4% ± 0.13%), CT-2S (56.32% ± 0.3%), CT-3L (67.0% ± 0.5%), and CT-3S (77.9% ± 0.2%). The major fatty acids found were palmitic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, margaric acid, melissic acid, and behenic acid. The most abundant fatty acid identified was palmitic acid: CT-1L (18.6% ± 0.08%), CT-1S (27.2% ± 0.04%), CT-2L (25.94% ± 0.04%), CT-2S (30.34% ± 0.03%), CT-3L (38.7% ± 0.03%), and CT-3S (26.60% ± 0.04%). Linoleic acid levels were: CT-1L (13.2% ± 0.06%), CT-1S (30.61% ± 0.03%), CT-2L (6.75% ± 0.04%), CT-2S (9.73% ± 0.02), CT-3L (3.15% ± 0.04%), and CT-3S (27.7% ± 0.2%); and linolenic acid levels were: CT-1L (16.1% ± 0.02%), CT-1S (0%), CT-2L (14.1% ± 0.03%), CT-2S (5.84% ± 0.03%), CT-3L (1.56% ± 0.05%), and CT-3S (11.05% ± 0.03%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fatty acids composition in Cassia tora leaves and stem

| S.N. | Compound name | Area (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| CT-1L | CT-1S | CT-2L | CT-2S | CT-3L | CT-3S | ||

| 1. | Caprylic acid | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | — | 0.23 ± 0.02 | — | — |

| 2. | Capric acid | — | — | — | 0.16 ± 0.01 | — | — |

| 3. | Valeric acid | — | — | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | — | — |

| 4. | Lauric acid | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | — | 0.85 ± 0.03 | — |

| 5. | Nonanoic acid | 0.63 ± 0.05 | — | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.01 | — | — |

| 6. | Myristic acid | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | |

| 7. | Pentadecyclic acid | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 5.03 ± 0.02 | — | 1.64 ± 0.04 | — |

| 8. | Undecanedioic acid | — | — | — | 0.24 ± 0.01 | — | — |

| 9. | Palmitic acid | 18.6 ± 0.08 | 27.2 ± 0.04 | 25.94 ± 0.04 | 30.34 ± 0.03 | 38.7 ± 0.03 | 26.60 ± 0.04 |

| 10. | Palmitoeic acid | 1.5 ± 0.04 | — | 1.66 ± 0.01 | — | 1.66 ± 0.02 | — |

| 11. | Margaric acid | 6.3 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | — | 4.85 ± 0.03 | 8.4 ± 0.01 | 8.64 ± 0.04 |

| 12. | Oleic acid | 11.2 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | — | — | — | — |

| 13. | Linoleic acid | 13.2 ± 0.06 | 30.61 ± 0.03 | 6.75 ± 0.04 | 9.73 ± 0.02 | 3.15 ± 0.04 | 27.7 ± 0.2 |

| 14. | Linolenic acid | 16.1 ± 0.02 | — | 14.1 ± 0.03 | 5.84 ± 0.03 | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 11.05 ± 0.03 |

| 15. | Nonadecyclic acid | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.036 ± 0.03 | — | — | 0.14 ± 0.01 | |

| 16. | Arachidic acid | 2.07 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | — | 2.4 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.05 |

| 17. | 9,12-Octadecatrienoic acid | — | — | — | 0.75 ± 0.02 | — | — |

| 18. | 17-Octadecynoic acid | — | — | 1.04 ± 0.02 | — | — | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| 19. | Henicosylic acid | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.053 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | — | — | — |

| 20. | Behenic acid | 1.26 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.15 | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.24 ± 0.03 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.01 |

| 21. | Tricosyclic acid | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | — | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| 22. | Tridecanoic acid | — | — | 1.05 ± 0.03 | — | — | — |

| 23. | Lignoceric acid | 1.64 ± 0.04 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.01 | — | 1.56 ± 0.2 | 0.67 ± 0.01 |

| 24. | Pentacosyclic acid | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 1.85 ± 0.04 | — | — | 0.22 ± 0.01 | — |

| 25. | Cerotic acid | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 3.6 ± 0.05 | — | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | — |

| 26. | Montanic acid | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 8.64 ± 0.12 | — | — | — | — |

| 27. | Melissic acid | 3.54 ± 0.04 | 1.6 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | — | 2.41 ± 0.02 | 0.64 ± 0.01 |

| Total | |||||||

| Others (unidentified) | 17.3 ± 0.06 | 21.05 ± 0.15 | 41.5 ± 0.13 | 43.6 ± 0.3 | 32.9 ± 0.5 | 22.0 ± 0.2 | |

| Identified | 82.6 ± 0.06 | 78.9 ± 0.15 | 58.4 ± 0.13 | 56.32 ± 0.3 | 67.0 ± 0.5 | 77.9 ± 0.2 | |

CT-1, Lucknow; CT-2, Nainital; CT-3, Gujarat; L, leaves; S, stem.

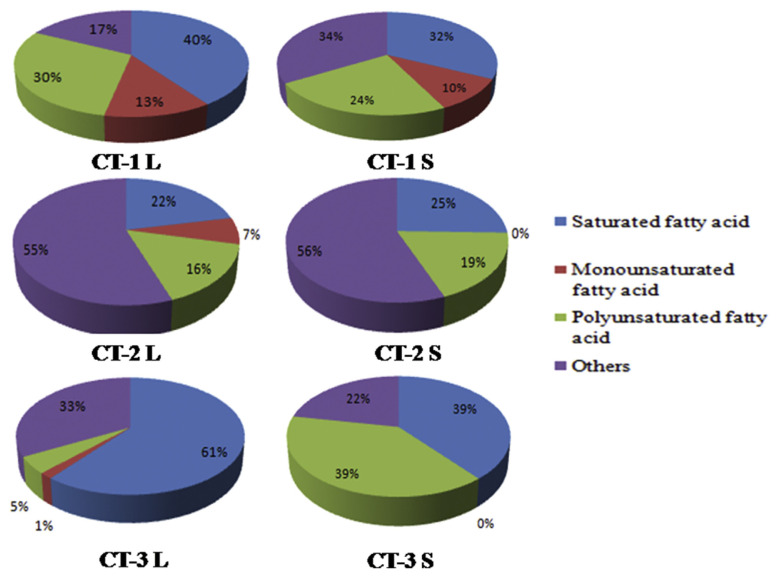

The saturated fatty acids found in high levels in CT-3L (60.7% ± 0.5%) in the petroleum ether extract of C. tora stem include palmitic acid, arachidic acid, margaric acid, myristic acid, and behenic acid (Figure 1). The monounsaturated fatty acids found in high levels in CT-1L (12.7% ± 0%) in petroleum ether extract of C. tora leaves include oleic acid and palmitoleic acid, whereas polyunsaturated fatty acids were high in CT-1S (30.6% ± 0.03%), including linoleic acid and linolenic acid, 9,12-octadecatrienoic acid, and 17-octadecynoic acid. Total unsaturated fatty acids found in CT-1 L (42.2% ± 0.05%) include total polyunsaturated fatty acids and total mono-unsaturated fatty acids as shown in Figure 1. The present investigation revealed the comparative study of the presence of fatty acids in the leaves and stem of C. tora collected from different geographical area, which can be used in various pharmaceutical products as it contains different bioactive constituents.

Figure 1.

Fatty acids categories in Cassia tora (Leaves, Stem). CT-1: Lucknow, CT-2 (Nainital), CT-3 (Gujarat), L (Leaves), S (Stem).

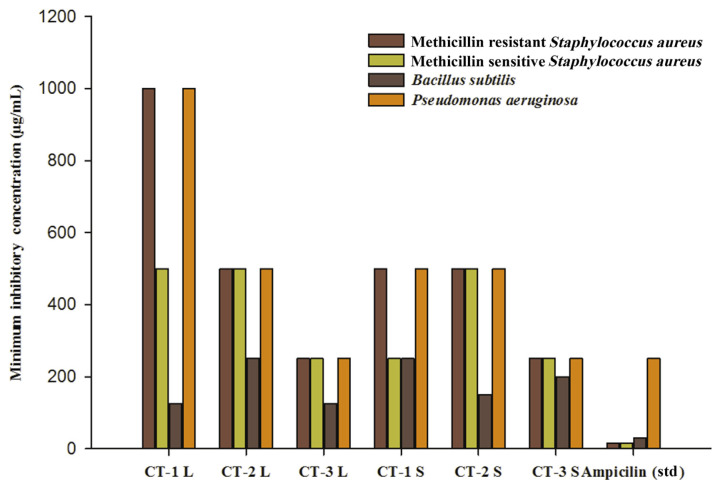

The FAME extracts showed antibacterial activity against four microorganisms: methicillin-resistant S. aureus, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, B subtilis, and P. aeruginosa. The lowest minimal inhibitory concentration value range (125–1000 μg/mL) was shown by CT-1L, CT-1S, CT-2L, CT-2S, CT-3L, and CT-3L, respectively, against B. subtilis bacteria. The ampicillin antibacterial positive control showed a minimal inhibitory concentration value range from 15.5 μg/mL to 250 μg/mL. These differences could be due to the nature and level of the antimicrobial agents present in the extracts and their mode of action on different test microorganisms (Figure 2) [11].

Figure 2.

Antibacterial Activity of Fatty acid methyl esters of Cassia tora Leaves and Stem. CT-1: Lucknow, CT-2 (Nainital), CT-3 (Gujarat), L (Leaves), S (Stem).

4. Discussion

In the present study, the gram-positive bacteria were more susceptible than the gram-negative bacteria. Similar results were obtained with FAME extracts of leaves of Ipomoea pescaprae and lipophilic extracts of various plant parts of Pistacia vera [12,13]. These differences in the fatty acid sensitivities between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria may result from the impermeability of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, since the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria is an effective barrier against hydrophobic substances [14,15]. In fact, gram-negative bacteria are more resistant to inactivation by medium- and long-chain fatty acids than gram-positive bacteria [16].

5. Conclusion

The present investigation reveals a new source of beneficial saturated and unsaturated fatty acids of significant value. Fatty acids were rich in palmitic, linoleic, and linolenic acids, which are beneficial for lowering body cholesterol if taken on daily basis as dietary supplements. The presence of palmitic, oleic, and stearic acids also increases the nutritional value and adds to the overall health benefits. Moreover, our study undoubtedly confirms that the FAME extracts of C. tora leaves and stems contain a relatively high percentage of the above-mentioned fatty acids, which have potential antibacterial properties that could be of use in clinical application.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Director of the National Botanical Research Institute, Lucknow, India, for providing the facilities to conduct the research work. The financial support received from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi under the project ‘Bio-prospection PR (BSC-0106)’ is duly acknowledged.

Funding Statement

The financial support received from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi under the project ‘Bio-prospection PR (BSC-0106)’ is duly acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mišurcová L, Ambrožová J, Samek D. Seaweed lipids as nutraceuticals. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2011;64:339–55. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387669-0.00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cakir A. Essential oil and fatty acid composition of the fruits of Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Sea Buckthorn) and Myrtus communis L. from Turkey. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2004;32(9):809–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGaw LJ, Jager AK, Van Staden J. Isolation of antibacterial fatty acids from Schotia brachypetala. Fitoterapia. 2002;73(5):431–3. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seidel V, Taylor PW. In vitro activity of extracts and constituents of Pelargonium against rapidly growing mycobacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;23(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abedi E, Sahari MA. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid sources and evaluation of their nutritional and functional properties. Food Sci Nutr. 2014;2(5):443–63. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Caterina R, Liao JK, Libby P. Fatty acid modulation of endothelial activation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1):213S–23S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.213S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joulain D, Konig WA. The atlas of spectral data of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons. Hamburg: EB-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mohtar M, Johari SA, Li AR, Isa MM, Mustafa S, Ali AM, Basri DF. Inhibitory and resistance-modifying potential of plant-based alkaloids against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Curr Microbiol. 2009;59(2):181–6. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorgensen JH, Turnidge JD, Washington JA, Murray PR, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Baron EJ, Yolken RH. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington: Geo F Brooks Publisher; 1999. Antibacterial susceptibility tests: dilution and disk diffusion methods; pp. 526–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eloff JN. A sensitive and quick microplate method to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration of plant extracts for bacteria. Planta Med. 1998;64(08):711–3. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barbour EK, Al Sharif M, Sagherian VK, Habre AN, Talhouk RS, Talhouk SN. Screening of selected indigenous plants of Lebanon for antimicrobial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chandrasekaran M, Venkatesalu V, Anantharaj M, Sivasankari S. Antibacterial activity of fatty acid methyl esters of Ipomoea pes-caprae (L.) Sweet. Indian Drugs. 2005;42(5):275–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Özçelik B, Aslan M, Orhan I, Karaoglu T. Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities of the lipophylic extracts of Pistacia vera. Microbiol Res. 2005;160(2):159–64. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galbraith H, Miller TB. Effect of long chain fatty acids on bacterial respiration and amino acid uptake. J Appl Bacteriol. 1973;36(4):659–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1973.tb04151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheu CW, Freese E. Lipopolysaccharide layer protection of gram-negative bacteria against inhibition by long-chain fatty acids. J Bacteriol. 1973;115(3):869–75. doi: 10.1128/jb.115.3.869-875.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kabara JJ. Food-grade chemicals for use in designing food preservative systems. J Food Prot. 1981;44(8):633–47. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-44.8.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]