Abstract

Pure cultures of methylotrophs and methanotrophs are known to oxidize methyl bromide (MeBr); however, their ability to oxidize tropospheric concentrations (parts per trillion by volume [pptv]) has not been tested. Methylotrophs and methanotrophs were able to consume MeBr provided at levels that mimicked the tropospheric mixing ratio of MeBr (12 pptv) at equilibrium with surface waters (≈2 pM). Kinetic investigations using picomolar concentrations of MeBr in a continuously stirred tank reactor (CSTR) were performed using strain IMB-1 and Leisingeria methylohalidivorans strain MB2T — terrestrial and marine methylotrophs capable of halorespiration. First-order uptake of MeBr with no indication of threshold was observed for both strains. Strain MB2T displayed saturation kinetics in batch experiments using micromolar MeBr concentrations, with an apparent Ks of 2.4 μM MeBr and a Vmax of 1.6 nmol h−1 (106 cells)−1. Apparent first-order degradation rate constants measured with the CSTR were consistent with kinetic parameters determined in batch experiments, which used 35- to 1 × 107-fold-higher MeBr concentrations. Ruegeria algicola (a phylogenetic relative of strain MB2T), the common heterotrophs Escherichia coli and Bacillus pumilus, and a toluene oxidizer, Pseudomonas mendocina KR1, were also tested. These bacteria showed no significant consumption of 12 pptv MeBr; thus, the ability to consume ambient mixing ratios of MeBr was limited to C1 compound-oxidizing bacteria in this study. Aerobic C1 bacteria may provide model organisms for the biological oxidation of tropospheric MeBr in soils and waters.

Methyl bromide (MeBr; CH3Br) is the major source of inorganic bromine in the stratosphere, making it an important contributor to stratospheric ozone depletion. MeBr accounts for 5 to 10% of stratospheric ozone destruction on a global basis (48). Use of MeBr as a fumigant is being phased out under amendments to the Montreal Protocol (49), but unlike many of the other compounds scheduled for phase out (e.g., chlorinated fluorocarbons), most of the MeBr released to the atmosphere is derived from natural sources.

The global MeBr budget as currently understood is out of balance because known sources do not balance identified sinks (3). Natural sources of MeBr include macroalgae, phytoplankton, fungi, higher plants (11, 20, 29, 37, 38, 53), and various types of wetlands (25, 36, 51). Sinks for MeBr are abiotic (hydrolysis and halide substitution) (21, 28) and biotic. In the oceans, microbial degradation of MeBr is widespread (45, 46). The processes of production and degradation occur simultaneously in the oceans, the balance of which results in a net sink for atmospheric MeBr (27). The biological mechanisms that control net flux are not well understood, but biotic sinks are of sufficient global magnitude to affect the atmospheric burden and lifetime of MeBr (41, 57).

Mechanistic studies with elevated MeBr concentrations (parts per million by volume [ppmv]) have demonstrated biodegradation in a variety of environments, including anaerobic sediments (35), fumigated agricultural soils (32), and a number of water types (5, 14). Experiments with soils have demonstrated that unidentified bacteria consume MeBr at ambient tropospheric mixing ratios (pptv) (16, 41, 52). Experiments with seawater have indicated that unidentified microbes are responsible for degradation at relatively low MeBr concentrations (≈100-fold above ambient) (28, 46).

Cometabolism of MeBr has been well documented in culture studies. Bacteria able to cooxidize MeBr include methanotrophs (13, 43), nitrifiers (10, 24), and certain marine methylotrophs that grow on dimethylsulfide or methanesulfonate (18; J. C. Murrell, personal communication). Investigations with specific inhibitors applied to environmental samples have shown that methanotroph/nitrifier cooxidation of ppmv MeBr was 50 to 72% in certain soils (34) and 82% in a freshwater lake (14). Methanotroph/nitrifier involvement was not detected in compost (34), agricultural soils (16, 32) or in marine and estuarine waters (14). The ability of methanotrophs in culture to consume pptv levels of MeBr has not been tested previously.

Certain facultative methylotrophs isolated from soil (strains IMB-1 and CC495) (6, 8) and from seawater (Leisingeria methylohalidivorans strain MB2T) (39) can grow with MeBr provided as the sole source of carbon and energy. Adding strain IMB-1 to soil increased the uptake of MeBr supplied at ppmv levels (6), and strains IMB-1 and MB2T fractionated stable carbon during MeBr oxidation (up to 72‰) (33). Such findings highlight MeBr-metabolizing bacteria as possible models for bacterial uptake of tropospheric MeBr. However, threshold concentrations for both growth and substrate degradation may exist (7), and the ability of such strains to consume tropospheric mixing ratios of MeBr (≈12 pptv) has not been tested directly. The ability of such bacteria to metabolize pptv mixing ratios of MeBr would corroborate degradation experiments conducted with marine waters and soils (16, 28, 41, 45, 46, 52), and it would support using these isolates for mechanistic studies of MeBr oxidation. In this work, we directly tested whether a number of bacteria, including methanotrophs and MeBr-metabolizing methylotrophs, could oxidize MeBr supplied at ambient MeBr mixing ratios.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of organisms.

Strain MB2T is a marine methylotroph recently identified as Leisingeria methylohalidivorans (ATCC BAA-92) (39). It was grown on marine broth (Difco 2216) either with or without MeBr or on a mineral salts medium (MAMS) supplied with MeBr as the sole carbon and energy source. The MAMS medium was adapted from that of Thompson et al. (44) and contained (in grams per liter): NaCl, 16; (NH4)2SO4, 1.0; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1.0; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.2; FeSO4 · 7H2O, 0.002; Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 0.002; Na2WO4, 0.003; KH2PO4, 0.36; K2HPO4, 2.34; and 1.0 ml of SL-10 trace metals (55). The phosphates were added after autoclaving from sterile stock solutions. The final pH of the medium was 6.9 to 7.1.

Ruegeria algicola (ATCC 51440) (47), a marine bacterium closely related to L. methylohalidivorans (97.5% identity) (39), was also grown on marine broth. R. algicola and L. methylohalidivorans are members of the Roseobacter group (also known as the marine alpha bacteria), a numerically dominant group of marine bacteria (12). Strain IMB-1 is a terrestrial methylotroph closely related to the genus Aminobacter (8, 23). It was grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Lennox; Difco) or on a defined mineral salts medium (Doronina medium [DM]) (40). When grown on DM, carbon and energy sources were supplied as MeBr (≈188 μM), glucose (15 mM), or both glucose and MeBr. Pseudomonas mendocina KR1, a toluene-oxidizing bacterium containing toluene-4-monooxygenase (T4MO), was grown with 100 μM toluene either on a mineral salt medium (31) or on LB broth. Bacillus pumilus and Escherichia coli were also grown on LB broth. Methylomonas rubra, a type 1 methanotroph, was grown on nitrate mineral salts medium (NMS) (54). Strain BB5.1, an estuarine methanotroph (42), was grown on NMS supplemented with 1.5% salt.

The methanotrophs were grown under a 50–50 methane-air atmosphere. Cells were grown using laboratory air; thus, they were exposed to ambient laboratory levels of MeBr during growth. Bacterial density was determined using acridine orange direct counts (AODC) (17). Three separate samples with a minimum of 8 grids per sample were counted for each experiment. The average percent coefficient of variation for AODC measurements was 17%.

Supplying pptv MeBr.

A three-stage dynamic dilution system supplied samples with a steady stream of an experimental atmosphere consisting of precise, near-ambient mixing ratios of MeBr (26). In brief, ultra-high-purity (UHP) air (99.999%; NE Air Gas) flowed through an oven held at 30°C ± 0.1°C, where it mixed with MeBr emitted from a gravimetrically calibrated permeation tube (KIN-TEK). The air flowed through a three-stage dilution box, where it was subsequently diluted with UHP air and/or bled from the system using mass flow controllers. The mass flow controllers were manually adjusted to produce the desired mixing ratio of MeBr. The permeation tube was weighed periodically over 5 years and determined to produce 16.8 ± 0.4 ng of MeBr min−1. The MeBr emitted at this permeation rate in conjunction with the supplied dilution air produced calibrated mixing ratios ranging from 6.4 to 2,000 pptv MeBr. MeBr was normally supplied to bacterial cell suspensions at a mixing ratio of 12.03 pptv to mimic the tropospheric mixing ratio of MeBr, which is 11.9 pptv in the northern hemisphere (27).

A sample pump and mass flow controller delivered the experimental air to the samples at a measured flow rate of 80 ml min−1. The experimental air was bubbled through 15 ml of culture placed in a gas washing tube fitted with a 19/22 frit (Corning; ML-1490-702). Equilibrium dissolved concentrations were calculated using the equations of King and Saltzman (28). The dissolved concentrations were 2.2 pM and 2.0 pM MeBr at 23°C for medium with no added salt and 16% salt, respectively. To verify that MeBr supersaturation did not occur, 15 ml of distilled (DI) water was flushed with experimental air for 20 min, and subsequently the sample was stripped for 30 min with UHP nitrogen to flush all the MeBr from the sample into the GC Cryotrap. The mass of MeBr recovered was in agreement with equilibrium calculations, indicating that supersaturation did not occur (data not shown).

Samples were equilibrated with experimental air for 20 min. A known volume of gas flowing from the fritted device was cryogenically trapped at −70°C using a GC Cryotrap (model 951; Scientific Instrument Services, Inc.) in conjunction with a totalizer/mass flow meter (MFM) (Brooks Instruments). The total volume of air was typically 400 ml, sampled over 20 min. The GC Cryotrap was heated to 120°C to volatilize the MeBr into the carrier gas stream of a Shimadzu GC-8A gas chromatograph equipped with an electron capture detector (GC-ECD). The carrier gas was oxygen-doped UHP nitrogen flowing at 12 ml min−1.

MeBr was separated using a precolumn (1 m by 0.16 cm outer diameter [o.d.]) packed with PoropakQ 100/120 mesh and an analytical column (2 m by 0.16 cm o.d.) packed with 80/100 mesh HayeSepQ (Alltech). Column and injector/detector temperatures were 140°C and 290°C, respectively. Standards from a gas cylinder were analyzed daily to verify the accuracy of the dilution system mixing ratios. The daily standard curves included replicates of the following five standards: 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 ml of 270 ppbv MeBr, corresponding to a range of 0.06 to 12 pmol of MeBr, which bracketed the range of masses delivered to the GC during experiments. The r2 of the linear regression fit of 6 months of GC response versus nanomoles of MeBr standard was 0.9998. The detection limit was ca. 0.04 pptv MeBr. Measurement precision typically was 5% (coefficient of variation [CV]).

Calculations for experiments supplied with pptv MeBr.

Consumption of MeBr was measured on duplicate live and control samples. Autoclaved cell suspensions and sterile medium behaved similarly (data not shown); thus, sterile medium typically was used as a control. Live cultures in late exponential phase were used, and uptake rates by live samples were corrected for any uptake observed in controls.

The experimental system functioned as a steady-state, continuously stirred tank reactor (CSTR). The mass balance equation (15) for the concentration of MeBr (nanomolar) in the influent (Cin) and effluent (Cout) gas is given in equation 1:

|

1 |

where Q is the gas flow rate (liters per hour), V is the liquid volume (0.015 L), and r is the rate of MeBr consumption which occurs in the liquid phase (nanomolar). By rearrangement, the rate of MeBr consumption can be expressed in terms of the gas phase concentrations:

|

2 |

For a reaction first-order in substrate and cell concentration, the rate of MeBr consumption can be expressed as follows (4):

|

3 |

where X is the cell density (cells per liter), CL is the concentration of MeBr in the liquid phase (nanomolar), and k is the apparent first-order reaction rate constant (per hour liter per cell). The exiting gas is in equilibrium with the liquid phase; therefore, CL = Cout/H, where H is the dimensionless Henry's constant for MeBr. The Henry's constant was calculated from the equations of De Bruyn and Saltzman (9); e.g., H = 0.22 at 23°C for medium without salt and H = 0.25 at 23°C for medium with 16 g of NaCl per liter. Combining equations 2 and 3 results in the following expression for the uptake rate of MeBr:

|

4 |

Equation 4 illustrates that a plot of the MeBr uptake rate, r/X, versus the liquid-phase MeBr concentration (CL) will be a straight line with a slope equal to the apparent first-order reaction rate constant (k). This relationship is illustrated in Fig. 1 and 2.

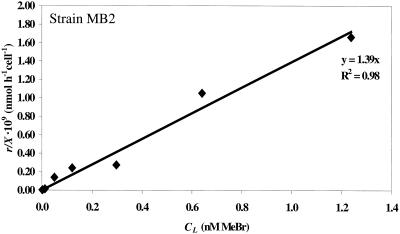

FIG. 1.

Uptake rate of MeBr by L. methylohalidivorans strain MB2T (r/X) versus the dissolved equilibrium concentration (CL). Concentrations correspond to supplied mixing ratios of 14 to 9,559 pptv MeBr. The slope of the line (1.4 × 10−9 h−1 liter cell−1) is equal to the apparent first-order rate constant, k, for this experiment (see equation 4).

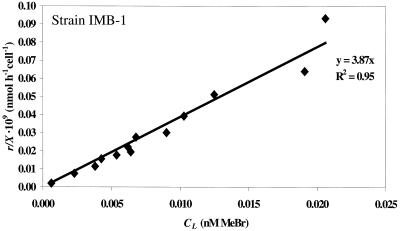

FIG. 2.

Uptake rate of MeBr by strain IMB-1 (r/X) versus the dissolved equilibrium concentration (CL). Concentrations correspond to supplied mixing ratios of 12 to 512 pptv MeBr. The slope of the line (3.9 × 10−9 h−1 liter cell−1) is equal to the apparent first-order rate constant, k, for this experiment (see equation 4).

Inhibition of protein synthesis.

Chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1) was used to assess the speed of turnover for MeBr-degrading enzymes. Strain IMB-1 was grown on glucose and 188 μM MeBr. The uptake rate of MeBr supplied at 12 pptv was measured for IMB-1 samples in the absence of chloramphenicol and for samples that were exposed to chloramphenicol 90 min prior to being placed into the gas washing tube. L. methylohalidivorans was grown on MAMS medium supplemented with MeBr (50 μM) as the sole carbon and energy source, or it was grown on marine broth with no additional MeBr. Chloramphenicol was added to L. methylohalidivorans in a fashion similar to that for strain IMB-1; however, no uptake of MeBr was observed under any conditions after 2 h of incubation (data not shown).

To better equalize the conditions between the control and treated samples and to normalize for possible general metabolic inhibition, chloramphenicol was added simultaneously to pairs of samples and for short durations. One sample received chloramphenicol soon after it was equilibrated with experimental air and just as the sample was being cryotrapped; thus, it was exposed to chloramphenicol during the 20 min it took to cryotrap the gas sample. The second sample received chloramphenicol at the same time, which was about 20 min before it was equilibrated with experimental air, and thus 40 min of cumulative exposure occurred before analysis.

Consumption of micromolar MeBr.

Strains IMB-1 and MB2T have been shown to readily consume MeBr provided at micromolar concentrations (39, 40). Other cultures tested here for uptake of picomolar MeBr (pptv) were also tested for their ability to consume micromolar levels of MeBr (ppmv). Cultures were grown in batch, and 10 ml of culture was added aseptically to 58-ml serum vials which were crimp sealed with blue butyl stoppers. MeBr was added to achieve a final concentration of 5 μM in the liquid phase for the methanotrophs M. rubra and strain BB5.1. R. algicola was tested for degradation using concentrations of 282, 141, 10, and 1 μM MeBr. P. mendocina KR1 was tested using concentrations of 5 and 1 μM MeBr.

Degradation of MeBr was monitored by injecting vial headspace (100 μl) into a Hewlett-Packard 5890 Series II GC-ECD. Experiments were performed using a Restek RTX-624 wide-bore capillary column (30 m, 0.53 μm i.d.; 3.0 μm depth of film). The oven, injector, and detector temperatures were 50°C, 240°C, and 300°C, respectively.

Batch kinetics of L. methylohalidivorans at micromolar concentrations.

Strain MB2T was grown on 50 μM MeBr in MAMS medium. The culture was diluted threefold with sterile medium, and 20 ml of diluted culture was added to 160-ml serum vials which were crimp sealed with blue butyl stoppers. MeBr was added to achieve final concentrations ranging from 0.18 to 29 μM and analyzed by GC-ECD as described above. Rates of MeBr degradation were determined by linear least-squares regression and normalized by cell density. The cell density ranged from 3.3 × 106 to 4.9 × 106 cells ml−1 for three separate experiments. Two replicate bottles were used for each concentration, and each bottle was sampled twice per time point. The data from three experiments (22 data points) were used to determine kinetic parameters by nonlinear least-squares regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Origin 6.0 software).

RESULTS

Ability of bacteria to consume 12 pptv MeBr.

A marine methylotroph (strain MB2T) and a terrestrial methylotroph (strain IMB-1) consumed MeBr supplied at a mixing ratio of 12 pptv (≈2 pM equilibrium dissolved concentration). Consumption of MeBr was first order in concentration for both organisms (Fig. 1 and 2). Neither a threshold for MeBr uptake nor saturation was observed for the concentrations applied here. The apparent degradation rate constants, k (equation 4), for strains MB2T and IMB-1 and the range of applied MeBr concentrations are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Average apparent first-order rate constants, k, for MeBr uptake

A terrestrial methanotroph (M. rubra) and an estuarine methanotroph (strain BB5.1) also consumed MeBr supplied at 12 pptv (Table 2). This appears to be the first direct demonstration that methanotrophic isolates can consume tropospheric levels of MeBr. These two methanotrophs were also able to completely remove 5 μM MeBr within 24 h (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Uptake rate of MeBr supplied at 12 pptv for different bacteriaa

| Sample | Mean uptake rate (10−8 pmol day−1 cell−1) ± SD |

|---|---|

| Strain MB2T | 6.0 ± 1.8 (n = 7) |

| Strain IMB-1 | 4.5 ± 1.1 (n = 5) |

| Methylomonas rubra | 8.1 ± 1.0 (n = 2) |

| Methylobacter sp. strain BB5.1 | 2.9 ± 1.5 (n = 3) |

| Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 | Not detected (n = 2) |

| Ruegeria algicola | Not detected (n = 4) |

| Escherichia coli | Not detected (n = 2) |

| Bacillus pumilus | Not detected (n = 2) |

Strains MB2T and IMB-1 were grown with MeBr as the sole source of carbon and energy. SD includes cumulative error for GC and AODC measurements.

No consumption of 12 pptv MeBr was observed for the heterotrophs B. pumilus and E. coli (Table 2). R. algicola, a phylogenetic relative of L. methylohalidivorans strain MB2T, also did not consume MeBr whether it was supplied at micromolar or picomolar levels. Similarly, P. mendocina KR1, which can cooxidize a variety of halogenated compounds (31), did not consume 12 pptv MeBr (Table 2), nor did it consume 1 or 5 μM MeBr even after 1 week of incubation (data not shown). Although the survey was not exhaustive, biodegradation of MeBr did not appear to be a universal trait of oxygenase-containing bacteria or a general trait of some common heterotrophs; in this study, the ability was limited to methylotrophs and methanotrophs.

Effect of growth conditions on MeBr uptake by strains MB2T and IMB-1.

Strains MB2T and IMB-1 consumed 12 pptv MeBr under most growth conditions. The presence of alternative growth substrates such as glucose did not appear to inhibit MeBr uptake, and both strains could consume 12 pptv MeBr whether or not they had been previously exposed to high levels of MeBr during growth (Table 3). On a per-cell basis, degradation rates were highest for cells grown on mineral medium with MeBr added as the sole source of carbon and energy (Table 3). Doubling the MeBr concentration from 154 to 330 μM during growth of strain IMB-1 had no adverse effect on uptake of near-ambient mixing ratios of MeBr, but increasing the growth concentration to 500 μM MeBr caused a marked decline in the consumption of 12 pptv MeBr (Table 3). Although strain IMB-1 can tolerate fairly high concentrations of MeBr (6, 40), doses in the 500 μM range appeared to be toxic.

TABLE 3.

Uptake rate versus growth condition for MeBr supplied at 12 pptv (∼2 pM) for terrestrial and marine methylotrophs

| Strain | Growth substrate and MeBr concn (μM) | Mean uptake ratea (10−8 pmol day−1 cell−1) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| MB2T | MeBr (50) | 7.6 ± 3.8 |

| Marine broth/MeBr (50) | 0.92 ± 0.10 | |

| Marine broth | 0.47 ± 0.07 | |

| IMB-1 | MeBr | |

| 330 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | |

| 500 | 0.096 ± 0.001 | |

| Glucose/MeBr | ||

| 154 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | |

| 188 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | |

| 330 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | |

| 500 | 0.0043 ± 0.0032 | |

| Methylamine/MeBr (330) | 0.44 ± 0.07 | |

| LB broth | 0.36 ± 0.16 |

SD includes cumulative error for GC and AODC measurements.

Inhibition of protein synthesis.

Consumption of 12 pptv MeBr by strain IMB-1 was not significantly affected by the addition of chloramphenicol (Table 4). Conversely, chloramphenicol did affect MeBr consumption by strain MB2T. Although uptake of MeBr was observed with a 20-min exposure of chloramphenicol, a 40-min exposure essentially inhibited uptake by cells grown on marine broth (Table 4). In a separate experiment, strain MB2T was actively growing on MeBr; thus, an ample supply of MeBr-degrading enzymes should have been available. Nonetheless, a 40-min exposure to chloramphenicol caused a 73% reduction in the MeBr uptake rate (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Uptake rate of MeBr supplied at 12 pptv versus growth condition and exposure time to chloramphenicola

| Strain | Growth substrate | Chloramphenicol exposure (min) | Mean uptake rate (10−8 pmol day−1 cell−1) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MB2T | Marine broth | 20 | 1.1 ± 0.17 |

| 40 | 0.1 ± 0.15 | ||

| MeBr (54 μM) | 20 | 4.1 ± 1.1 | |

| 40 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | ||

| IMB-1 | Glucose/MeBr (188 μM) | 0 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| 90 | 0.18 ± 0.05 |

Chloramphenicol was added to paired samples simultaneously (see text.) SD includes cumulative error for GC and AODC measurements.

Batch kinetics for L. methylohalidivorans

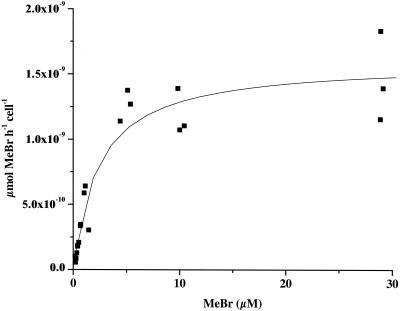

Saturation kinetics were observed for strain MB2T (Fig. 3). Nonlinear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation produced values of Vmax = 1.6 ± 0.1 nmol h−1 (106 cells)−1 and Ks = 2.4 ± 0.6 μM.

FIG. 3.

Saturation kinetics for L. methylohalidivorans strain MB2T. The line represents a nonlinear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

DISCUSSION

The role of microorganisms in controlling the biogeochemistry of trace gases such as methane (CH4) and MeBr appears to be pronounced (7, 16, 41). However, the biological oxidation of tropospheric CH4 (≈1.75 ppmv) by soil methanotrophs poses a physiological paradox because more energy is expended in the production and maintenance of enzymes like CH4 monooxygenase (MMO) than can be recovered from the available substrate (7). Thresholds for methane (CH4) degradation and a biphasic pattern have been reported for CH4 oxidation in soils (1), raising questions about how bacteria consume trace gases from the atmosphere. Tropospheric mixing ratios of MeBr are about five orders of magnitude lower than those of CH4, so MeBr poses an even greater physiological paradox from the standpoint of energy yields. It was thus questionable whether previously characterized CH4- or MeBr-oxidizing bacteria would have any detectable affinity for 12 pptv levels of MeBr.

To directly address this issue, we measured the kinetics of MeBr degradation starting with near-ambient mixing ratios of MeBr. The methanotrophs and methylotrophs tested were able to consume MeBr supplied at 12 pptv (Table 2). Furthermore, the methylotrophic strains MB2T and IMB-1 showed clear first-order kinetics with no apparent threshold or biphasic pattern (Fig. 1 and 2).

Kinetic saturation was not reached in these experiments (Fig. 1 and 2), precluding the calculation of Ks and Vmax. However, these parameters were measured in batch experiments for L. methylohalidivorans strain MB2T (Fig. 3). The apparent first-order reaction rate constant (k) can be estimated as Vmax/Ks for S ≪ Ks. This value, 0.67 × 10−9 h−1 liter cell−1, is equivalent to the rate constant obtained from the CSTR experiments (Table 1). Kinetic parameters previously were measured in batch experiments for strain IMB-1 by Schaefer and Oremland (40). They reported values of Ks = 190 nM and Vmax = 210 pmol h−1 (106 cells)−1. The resulting value for Vmax/Ks, 1.1 × 10−9 h−1 liter cell−1, is equivalent to the rate constant obtained from the CSTR experiments for strain IMB-1 (Table 1). Note that the reported rate constant of 0.056 h−1 for a cell density of 106 cells was actually for a cell density of 106 cells per 20 ml of cell suspension (J. K. Schaefer, personal communication).

The CSTR employed near-ambient concentrations, whereas the batch experiments used MeBr concentrations that were 35 to 1 × 107 times higher. Nonetheless, the values of Ks and Vmax determined in batch experiments adequately described the apparent rate constants measured using the CSTR. For strains MB2T and IMB-1, Ks values were 102 to 103 times higher than concentrations of MeBr that could be supplied from the troposphere. Even so, both strains were able to consume environmentally relevant levels of MeBr.

Known methanotrophs and soil bacteria consuming ambient levels of CH4 differ in kinetic properties (1), and methanotrophs in culture may not represent those active in soil (19). However, methanotrophs in culture and in soils can oxidize tropospheric mixing ratios of CH4 when provided with a source of reducing equivalents, such as methanol (2) suggesting that soil methanotrophs may be supported by more-abundant C1 compounds in the environment (22). A similar situation may exist for facultative methylotrophs that respire methyl halides, namely, they may consume MeBr from the atmosphere while their growth is supported by other substrates available at higher concentrations in their local milieu. This theory is supported here in that the tested MeBr-utilizing bacteria were able to consume 12 pptv MeBr while grown on alternative substrates (Table 3).

Oxidation of MeBr by methanotrophs and nitrifiers does not support growth (cometabolism) and proceeds via monooxygenase enzymes (24, 34, 43). In contrast, strains IMB-1 and MB2T respire MeBr (6, 39), and this process appears to be mediated by a methyltransferase (8, 30, 50, 56). Consumption of >100 μM MeBr is inducible in strain IMB-1 (40), and the induced proteins have been identified (56). However, strain IMB-1 was inferred to have some low level of methyltransferase present constitutively, because washed cells grown on glucose were able to consume 18 nM MeBr after exposure to chloramphenicol (40).

Those results were supported here in that significant uptake of 12 pptv MeBr was measured in strain IMB-1 after a 90-min exposure to chloramphenicol (Table 4). Both of these methylotrophs appeared to have some constitutive level of methyltransferase because cultures grown without added MeBr could consume 12 pptv MeBr (Table 3). In the case of strain MB2T, however, MeBr uptake rates decreased rapidly in the presence of chloramphenicol for both MeBr-grown and marine broth-grown cells (Table 4), suggesting that there was rapid turnover of the enzyme(s) responsible for the uptake of ambient MeBr.

It is possible that the induced proteins identified in strain IMB-1 (56) are responsible for MeBr degradation at both picomolar and micromolar levels but that the level of constitutive protein was not adequate to appear on protein gels. However, it is also possible that more than one MeBr-degrading system operates in strain IMB-1 and that the enzymes induced at >100 μM may not fully represent the enzymes responsible for degradation at picomolar levels. The latter case could have important consequences for the use of gene probes (30, 56).

The ability to consume 12 pptv MeBr was not observed for all the bacteria tested. Bacteria unable to consume 12 pptv MeBr included two common heterotrophs (B. pumilus and E. coli), a member of the marine Roseobacter group (12) (R. algicola), and a bacterium able to cooxidize a variety of halogenated compounds (P. mendocina KR1). In contrast, all four of the tested C1 bacteria were able to consume MeBr supplied at 12 pptv (Table 2). While these results comprise a limited survey, they suggest that the ability to oxidize ambient mixing ratios of MeBr is not a universal trait among “common” bacteria or bacteria utilizing oxygenases. Furthermore, the ability to oxidize methyl halides is not necessarily shared among closely related species, as was seen for L. methylohalidivorans strain MB2T and R. algicola.

Finally, increased understanding of biogeochemical cycles arises from mechanistic studies using bacterial isolates only to the degree that the organisms studied in the laboratory represent environmental processes. Environmentally relevant concentrations were used in this study, linking previous research from the organism level (bacteria isolated from soil and seawater) to studies at the ecosystem level (biodegradation in soil and seawater). This study demonstrated that certain C1 compound-utilizing bacteria are capable of consuming 12 pptv mixing ratios of MeBr. These results suggest that such organisms can serve as laboratory models to complement environmental studies and highlight the observed biotic uptake of ambient MeBr in waters and soils.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Schaefer for aid in maintaining cultures at the USGS, A. Sardeshmukh for counting AODC samples at CIMAS, and A. Mosedale and C. Mosedale for laboratory assistance at UNH. We thank K. McClay for supplying P. mendocina KR1.

This research was supported by cooperative agreement NA67RJ0-149 of CIMAS (University of Miami and NOAA), the USGS, and NASA grant 5188-AU-0080 to R.S.O.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender M, Conrad R. Kinetics of CH4 oxidation in oxic soils exposed to ambient air or high CH4 mixing ratios. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1992;101:261–270. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benstead J, King G M, Williams H G. Methanol promotes atmospheric methane oxidation by methanotrophic cultures and soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1091–1098. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1091-1098.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler J H. Better budgets for methyl halides? Nature. 2000;403:260–261. doi: 10.1038/35002232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Button D K. Biochemical basis for whole-cell uptake kinetics: specific affinity, oligotrophic capacity, and the meaning of the Michaelis constant. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;577:2033–2038. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.2033-2038.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell T L, Joye S B, Miller L G, Oremland R S. Bacterial oxidation of methyl bromide in Mono Lake, California. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:1489–1495. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connell Hancock T L, Costello A M, Lidstrom M E, Oremland R S. A novel bacterium for the dissipation of methyl bromide in fumigated agricultural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2899–2905. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2899-2905.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad R. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO) Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:609–640. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.609-640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulter C, Hamilton J T G, McRoberts W C, Kulakov L, Larkin M J, Harper D B. Halomethane:bisulfide/halide ion methyltransferase, an unusual corrinoid enzyme of environmental significance isolated from an aerobic methylotroph using chloromethane as the sole carbon source. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4301–4312. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4301-4312.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bruyn W J, Saltzman E S. The solubility of methyl bromide in pure water, 35% sodium chloride and seawater. Mar Chem. 1997;56:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duddleston K N, Bottomley P J, Porter A, Arp D J. Effects of soil and water content on methyl bromide oxidation by the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2636–2640. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2636-2640.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan J, Yates S R, Ohr H D, Sims J J. Production of methyl bromide by terrestrial higher plants. Geophys Res Lett. 1998;25:3595–3598. [Google Scholar]

- 12.González J M, Moran M A. Numerical Dominance of a group of marine bacteria in the α-subclass of the class Proteobacteria in coastal seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4237–4242. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4237-4242.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodwin K D, Lidstrom M E, Oremland R S. Marine bacterial degradation of brominated methanes. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:3188–3192. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin K D, Schaefer J K, Oremland R S. Bacterial oxidation of dibromomethane and methyl bromide in natural waters and enrichment cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4629–4636. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4629-4636.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill C G., Jr . An introduction to chemical engineering kinetics and reactor design. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1977. Basic concepts in reactor design and ideal reactor models; pp. 245–316. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hines M E, Crill P M, Varner R K, Talbot R W, Shorter J H, Kolb C E, Harriss R C. Rapid consumption of low concentrations of methyl bromide by soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1864–1870. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1864-1870.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hobbie J E, Daley R L, Jaspar S. Use of Nuclepore filters for counting bacteria for fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1225–1228. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1225-1228.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoeft S E, Rogers D R, Visscher P T. Metabolism of methyl bromide and dimethyl sulfide by marine bacteria isolated from coastal and open waters. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2000;21:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes A J, Roslev P, McDonald I R, Iversen N, Henriksen K, Murrell J C. Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3312–3318. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3312-3318.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh N, Tsujita M, Ando T, Hisatomi G, Higashi T. Formation and emission of monohalomethanes from marine algae. Phytochemistry. 1997;45:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffers P M, Wolfe N L. On the degradation of methyl bromide in sea water. Geophys Res Lett. 1996;23:1773–1776. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen S, Priemè A, Bakken L. Methanol improves methane uptake in starved methanotrophic microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;63:1143–1146. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1143-1146.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kämpfer P, Müller C, Mau M, Neef A, Auling G, Busse H-J, Osborn A M, Stolz A. Description of Pseudaminobacter gen. nov. with two new species, Pseudaminobacter salicylatoxidans sp. nov. and Pseudaminobacter defluvii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:887–897. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keener W K, Arp D J. Kinetic studies of ammonia monooxygenase inhibition in Nitrosomonas europaea by hydrocarbons and halogenated hydrocarbons in an optimized whole-cell assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2501–2510. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2501-2510.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keppler F, Elden R, Niedan V, Pracht J, Schöler H F. Halocarbons produced by natural oxidation processes during degradation of organic matter. Nature. 2000;403:298–300. doi: 10.1038/35002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerwin R A, Crill P M, Talbot R W, Hines M E, Shorter J H, Kolb C E, Harriss R C. Determination of atmospheric methyl bromide by cryotrapping-gas chromatography and application to soil kinetic studies using a dynamic dilution system. Anal Chem. 1996;68:899–903. doi: 10.1021/ac950811z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King D B, Butler J H, Montzka S A, Yvon-Lewis S A, Elkins J W. Implications of methyl bromide supersaturations in the temperate North Atlantic Ocean. J Geophys Res. 2000;105:19763–19769. [Google Scholar]

- 28.King D B, Saltzman E S. Removal of methyl bromide in coastal seawater: chemical and biological rates. J Geophys Res. 1997;102:18715–18721. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manley S L, Dastoor M N. Methyl halide (CH3X) production from the giant kelp Macrocystis, and estimates of global CH3X production by kelp. Limnol Oceanogr. 1987;32:709–715. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAnulla C, Woodall C A, McDonald I R, Studer A, Vuilleumier S, Leisinger T, Murrell J C. Chloromethane utilization gene cluster from Hyphomicrobium chloromethanicum strain CM2T and development of functional gene probes to detect halomethane-degrading bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:307–316. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.307-316.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClay K, Fox B G, Steffan R J. Chloroform mineralization by toluene-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2716–2722. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2716-2722.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller L G, Connell T L, Guidetti J R, Oremland R S. Bacterial oxidation of methyl bromide in fumigated agricultural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4346–4354. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4346-4354.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller L G, Kalin R M, McCauley S E, Hamiliton J T G, Harper D B, Millet D B, Oremland R S, Goldstein A H. Large carbon isotope fractionation associated with oxidation of methyl halides by methylotrophic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5833–5837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101129798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oremland R S, Miller L G, Culbertson C W, Connell T L, Jahnke L L. Degradation of methyl bromide by methanotrophic bacteria in cell suspensions and soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3640–3646. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3640-3646.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oremland R S, Miller L G, Strohmaier F E. Degradation of methyl bromide in anaerobic sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:514–520. doi: 10.1021/es00052a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhew R C, Miller B R, Weiss R F. Natural methyl bromide and methyl chloride emissions from coastal salt marshes. Nature. 2000;403:292–295. doi: 10.1038/35002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sæmundsdóttir S, Matrai P A. Biological production of methyl bromide by cultures of marine phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scarratt M G, Moore R M. Production of methyl chloride and methyl bromide in laboratory cultures of marine phytoplankton. Mar Chem. 1996;54:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaefer J K, Goodwin K D, McDonald I R, Murrell J C, Oremland R S. Leisingeria methylohalidivorans, gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine methylotroph that grows on methyl bromide. 2001. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaefer J K, Oremland R S. Oxidation of methyl halides by the facultative methylotroph, strain IMB-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;64:5035–5041. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5035-5041.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shorter J H, Kolb C E, Crill P M, Kerwin R A, Talbot R W, Hines M E, Harriss R C. Rapid degradation of atmospheric methyl bromide in soils. Nature. 1995;377:717–719. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith K S, Costello A M, Lidstrom M E. Methane and trichloroethylene oxidation by an estuarine methanotroph, Methylobacter sp. strain BB5.1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4617–4620. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4617-4620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stirling D I, Dalton H. Oxidation of dimethyl ether, methyl formate and bromomethane by Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) J Gen Microbiol. 1980;116:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson A S, Owens N J P, Murrell J C. Isolation and characterization of methanesulfonic acid-degrading bacteria from the marine environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2388–2393. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2388-2393.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tokarczyk R, Saltzman E S. Methyl bromide loss rates in surface waters of the North Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Eastern Pacific Ocean (8°N to 45°N) J Geophys Res. 2001;106:9843–9851. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tokarczyk R, Goodwin K D, Saltzman E S. Methyl bromide loss rate constants in the North Pacific Ocean (11°N to 57°N). 2001. Geophys. Res. Lett., in press. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uchino Y, Hirata A, Yokota A, Sugiyama J. Reclassification of marine Agrobacterium species: proposals of Stappia stellulata gen. nov., comb. nov., Stappia aggregata sp. nov., nom. rev., Ruegeria atlantica gen. nov., comb. nov., Ruegeria gelatinovora comb. nov., Ruegeria algicola comb. nov., and Ahrensia kieliense gen. nov., sp. nov., nom. rev. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1998;44:201–210. doi: 10.2323/jgam.44.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.United Nations Environment Programme. Methyl bromide: its atmospheric science, technology and economics. Montreal Protocol assessment supplement. Synthesis report of the methyl bromide interim scientific assessment and methyl bromide interim technology and economic assessment. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 49.United Nations Environment Programme. Report of the methyl bromide technical options committee for the 1995 assessment of the UNEP Montreal Protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme Nairobi; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vannelli T, Studer A, Ketesz M, Leisinger T. Chloromethane metabolism by Methylobacterium sp. strain CM4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1933–1936. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1933-1936.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varner R K, Crill P M, Talbot R W. Wetlands: a potentially significant source of atmospheric methyl bromide and methyl chloride. Geophys Res Lett. 1999;26:2433–2436. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varner R K, Crill P M, Talbot R W, Shorter J H. An estimate of the uptake of atmospheric methyl bromide by agricultural soils. Geophys Res Lett. 1999;26:727–730. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watling R, Harper D B. Chloromethane production by wood-rotting fungi and an estimate of the global flux to the atmosphere. Mycol Res. 1998;1027:769–787. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whittenbury R, Dalton H. The methylotrophic bacteria. In: Starr M P, Stolp H, Truper H G, Balows A, Schlegel H G, editors. The prokaryotes. I. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1981. pp. 895–902. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Widdel F, Kohring G-W, Mayer F. Studies on the dissimilatory sulfate that decomposes fatty acids. III. Characterization of the filamentous gliding Desulfonema limicola gen. nov., sp. nov., and Desulfonema magnum sp. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1983;134:286–294. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodall C A, Warner K, Oremland R S, Murrell J C, McDonald I R. Identification of methyl halide-utilizing genes in strain IMB-1, a methyl bromide-utilizing bacterium, suggests a high degree of conservation of methyl halide-specific genes in gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1959–1963. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1959-1963.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yvon-Lewis S A, Butler J H. The potential effect of oceanic biological degradation on the lifetime of atmospheric CH3Br. Geophys Res Lett. 1997;24:1227–1230. [Google Scholar]