Abstract

Purpose of Review

Trauma and posttraumatic stress are common among individuals with chronic pain and contribute to increased morbidity and impairment. Individuals with trauma and chronic pain may be prone to non-suicidal self-injury, a relatively common yet risky self-regulatory behavior. There is a dearth of research on the intersection of trauma, chronic pain, and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). We conducted a systematic review of the extant literature.

Recent Findings

Five quantitative and eight case reports were identified. Only one quantitative study reported specifically on NSSI. Self-harm rates varied across studies, though appeared elevated among patients with chronic pain. Childhood trauma was linked to this co-occurrence.

Summary

Causal links between trauma, NSSI, and pain are proposed, highlighting the need for a comprehensive theoretical model. We recommend assessing for childhood trauma when treating patients with chronic pain and querying regarding NSSI when patients present with indicators of NSSI risk and to treat or refer such patients to specialized treatment.

Keywords: Abuse, Central sensitization, NSSI, Pain, PTSD, Self-harm

Introduction

The presence of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress is increasingly studied in chronic pain populations and associated with increased pain experiencing, morbidity, functional impairment, and healthcare utilization [1–9]. Meta-analytic findings reveal that individuals who have experienced trauma or abuse are nearly three times more likely than those with no trauma to display one of several functional somatic syndromes, including fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, and temporomandibular joint syndrome [10]. Explanatory models propose deficits in emotion regulation as a key factor in the trauma-pain relationship [11–13], both precipitating and perpetuating pain symptoms [14••]. One way in which patients with both chronic pain and trauma history may attempt to regulate emotion states is through acts of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). NSSI consists of damage inflicted on one’s own body without the intent to die [15], also sometimes referred to as parasuicidal or self-injurious behavior (Table 1). Examples of NSSI acts include self-inflicted cutting, burning, and head-banging, with some including other behaviors with indirect negative physical consequences such as intentional overdose on drugs. NSSI in particular is conceptualized as a behavioral strategy that may be used to obtain a number of outcomes, including affect modulation or communication of distress to others [16••].

Table 1.

Definitions of terms used to refer to self-injurious behavior

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Self-harm/self-injurious behavior (SIB) | Includes both suicidal and non-suicidal forms of self-injury, including attempted/completed suicide and self-injury without intent to die |

| Suicidal behavior | Includes attempted and/or completed suicide |

| Parasuicidal behavior | More narrow in definition than suicidal behavior, but with mixed use in the literature; generally refers to self-injury that may or may not be suicidal and may include ambivalent or non-suicidal self-injury [28, 29] |

| Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) | Intentional damage to one’s body without the intention to kill oneself. Some definitions require direct and immediate damage to bodily tissue [15], while others include a broader range of behaviors such as medication abuse or restrictive eating [30, 31] |

NSSI is relatively common, occurring in over 15% of adolescents and 13% of young adults, and declines in prevalence with age with roughly 5% of adults engaging in NSSI [16••, 17–19]. NSSI is more common among women [20] and is associated with exposure to trauma [21] and the presence of posttraumatic stress disorder [22]. Recent studies have linked NSSI to a range of forms of childhood trauma [23, 24] particularly sexual abuse [25], with up to 50–60% of individuals who engage in self-harm endorsing a trauma history [26]. NSSI confers risk for suicide attempts, with some evidence suggesting four times greater odds of attempting suicide given a history of NSSI [27], though it is conceptualized as distinct from suicidal self-injurious behavior [15] (Table 1). Together, this research implicates NSSI as an important and prevalent behavior to understand and prevent.

Burgeoning research has begun to explore the rates of self-harm and NSSI among patients with chronic pain, finding sobering evidence of elevated rates of self-harm among these individuals. Specific pain populations appear at greater risk of engaging in self-harm behaviors, which can occur at a two-fold increased incidence rate (i.e., up to 10–25% of patients endorsing self-harm) in syndromes such as fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic back pain compared to patients without these disorders [32, 33]. The link between recurrent, diffuse pain, and NSSI has also been revealed among adolescents, with more than 30% of adolescents with recurrent pain endorsing a history of NSSI [34]. Mixed findings of existing research [32, 35] suggest that self-harm behavior may be related to specific pain conditions or other unmeasured factors unique to specific pain populations. A number of studies have highlighted the importance of emotion regulation as a mechanism by which patients with chronic pain may alleviate their symptom burden [36, 37•], highlighting a potential role of NSSI use among these individuals. However, multiple existing studies combine both suicidal and non-suicidal forms of self-harm, and thus the specific association between chronic pain conditions and NSSI remains underexamined.

In order to elucidate the associations between trauma, chronic pain, and NSSI, we completed a systematic literature search of the extant, though sparse, literature that has focused simultaneously on these three clinical phenomena. Our search and subsequent review combine the quantitative and qualitative literature on these phenomena in order to best describe the existing knowledge base regarding how these constructs might interact. Whereas quantitative research is ideal for determining the actual prevalence rates of and strength of associations among these co-occurring phenomena, case studies help to tease apart the underlying causal links giving rise to the correlations seen in quantitative research. We then provide (1) a summary and integration of the existing literature, (2) clinical recommendations based on the existing literature, and (3) suggestions for future research.

Method

Inclusion Criteria and Search Strategy

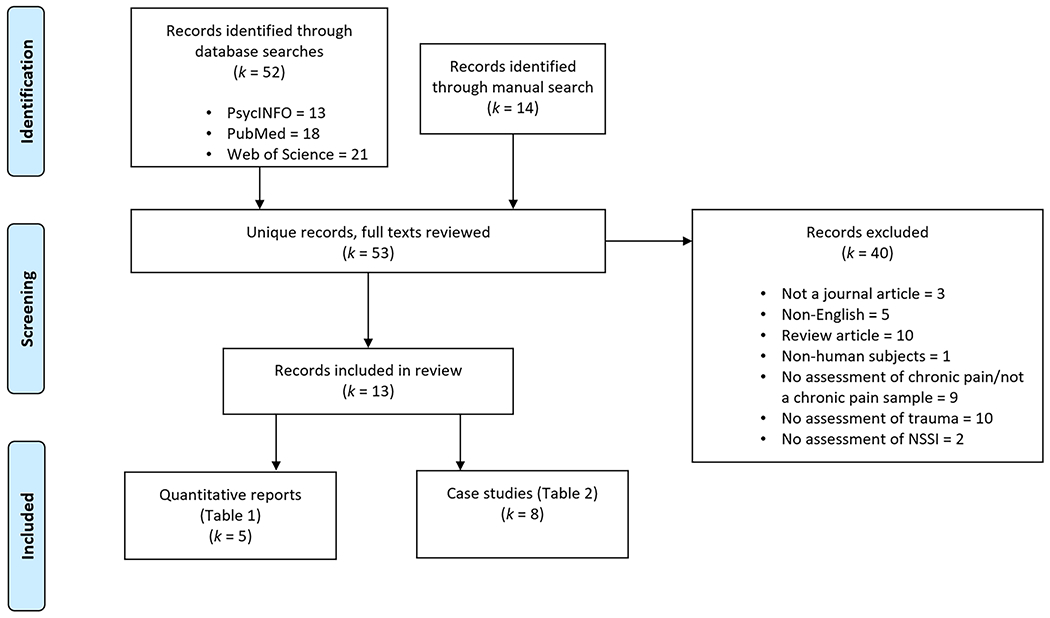

We performed a systematic review of the literature in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Framework [38]. We included three science literature databases: Pub-Med including MEDLINE, EBSCO PsycINFO, and Web of Science (Core Collection). The primary search was conducted on May 17, 2021, including all articles published in these databases prior to that date.

We sought articles that included mention of all three of the relevant conceptual domains of interest (chronic pain, trauma, and NSSI). The search was restricted to only peer-reviewed journal articles. Articles were included if terms appeared in any database field, including title, abstract, and keywords. Search terms were as follows:

(“chronic pain” OR “widespread pain” OR “persistent pain” OR “central* sensitiz*”)

AND (“trauma” OR “PTSD” or “post-traumatic” or “posttraumatic” OR “abuse”)

AND (“self-harm” OR “self-inj*” OR “self-mutilation” OR “parasuic*” OR “para-suic*” OR “NSSI”)

We also included a subset of articles culled from reference lists of relevant articles or from other sources. These were evaluated based on the same criteria as articles derived from the database search.

Study inclusion criteria included: (1) peer-reviewed journal article; (2) available in English; (3) not a conceptual paper, narrative or systematic review or meta-analysis (empirical/quantitative and case studies/case series were included); (4) includes human subject(s); (5) assesses chronic pain and/or includes chronic pain subsample; (6) assesses trauma as defined according to DSM-5 [39] and/or ICD-11 [40] definitions and/or includes subject(s) with such trauma articulated in report; and (7) assesses and/or reports on self-harm, including NSSI (i.e., does not only assess suicidal self-harm/suicide attempts/ideation), even if NSSI is not assessed in isolation (i.e., combined with suicidal self-harm). The use of a validated instrument or comprehensive measure of trauma, pain, or self-harm was not required.

Identified studies were screened for duplicates and subsequently underwent full-text review according to the criteria above. The first author determined initial eligibility of studies, and the list was finalized by consultation with the second author. For each quantitative study, we tabulated several sample characteristics (sample size, % female, mean age) as well as the description of assessment and prevalence rates (when available) of chronic pain, trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self-harm, and NSSI. Given the exploratory nature of this review and the relative dearth of expected identified reports, we did not conduct quantitative meta-analyses or assess publication bias or study quality and instead provide a descriptive summary and narrative review of the identified reports.

Results

Results of Search and Classification of Articles

From database searches (k = 52) and manual searches (k = 14), a total of 53 unique reports were screened, resulting in 13 reports reviewed after exclusion of ineligible reports (Fig. 1). Five of these were quantitative/empirical papers, including one retrospective cohort study [41] and four cross-sectional observational cohort studies [42–45] (Table 2). Eight additional studies included five case studies [46–50] and three case series [51–53] (Table 3). Only one study was published within the past 5 years [41]. No study provided prospective or longitudinal data or utilized experimental manipulation.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study identification, screening, and inclusion for review

Table 2.

Summary of reviewed quantitative/empirical studies (k = 5)

| Year | Author(s) | N | % Female | Average age | Study type | Sample | Assessment of chronic pain | Assessment of trauma | Assessment of self-harm | Rate of chronic pain diagnosis | Rate of trauma | Rate of PTSD | Rate of Self-Harm | Rate of NSSI | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Hayes et al | 56,187 | 9.6% | 57.2 | Retrospective cohort study | Veterans with chronic, non-cancer pain on long-term opioid therapy | Medical record diagnosis of arthritis, back pain, neck pain, neuropathic pain, or headache/migraine | Medical record diagnosis of PTSD | Medical record designation of ICD-9 self-injury code (E950-E959 & V62.84) | 100% | N/A | 5.6% | 1.5% | N/A | Patients with increasing opioid treatment dosages reported higher rates of self-injury than those with maintained opioid dosages (over 1 year), controlling for PTSD, average pain, and other covariates. |

| 2011 | Okifuji & Benham | 260 | 62% | 41.7 | Cross-sectional clinical interview study | Consecutively admitted adult patients presenting to University-based, tertiary-care, multidisciplinary pain treatment center | “Comprehensive, interdisciplinary pain evaluation” | Semi-structured interview of history of childhood sexual and physical abuse and adulthood experience of domestic violence | Clinical evaluation: 1. “Have you done anything in the past to intentionally harm yourself?” 2. “What did you do?” 3. “What happened after you did it?” 4. “Did you mean to kill yourself or want to die at that point?” |

100% | 19% childhood sexual abuse 18% childhood physical abuse 9% adult domestic abuse | N/A | 25.4% | 18.8% | Only 4 (6.1%) of self-harmers reported both suicide and NSSI histories, suggesting little overlap between these subpopulations. Childhood physical and sexual abuse, but not adult domestic violence, was associated with increased rates of Hx of NSSI (though not Hx of suicide attempts or presence of current SI). |

| 2009 | Sansone et al | 117 | 62.4% | 44.5 | Cross-sectional clinical interview/self-report study | Consecutively recruited adult patients with chronic, non-cancer pain referred to a pain management specialist | Clinical evaluation of chronic pain | Self-report evaluation of childhood trauma: “Prior to the age of 12, did you ever experience [sexual/physical/emotional abuse, physical neglect, witness violence]?” [yes/no] | Self-Harm Inventory (Sansone et al., 1998) | 100% | N/A (not reported) | N/A | 52.1% | N/A | Found comparable strength of associations (moderate to large) between sexual, physical, emotional, and vicarious traumas and self-harm, assessed regardless of suicidal intent. Furthermore, found that 21.4% of patients endorsed a history of five or more types of self-harm. |

| 2006 | Sansone et al | 87 | 58.6 % | 43 | Cross-sectional self-report study | Convenience sample of adult out-patients at an internal medicine training clinic associated with a community hospital | Pain disorders self-reported, though sample recruited from internal medicine clinic | Self-report evaluation of childhood trauma: “Prior to the age of 12, did you ever experience [sexual/physical/emotional abuse, physical neglect, witness violence]?” [yes/no] | Self-Harm Inventory (Sansone et al., 1998) | < 100% (78 diagnoses; unknown # of patients Dxd) | N/A (not reported) | N/A | N/A (not reported; 19.5% endorsed a Hx of 5 or more types of SH) | N/A | Physical abuse, emotional abuse, and witnessing violence (but not sexual abuse or physical neglect) were each significantly associated (small-to-moderate correlation) with the number of pain disorders endorsed. Only witnessing violence was uniquely predictive. |

| 2001 | Sansone et al | 17 | 70.6 % | 48.9 | Cross-sectional clinical interview/self-report study | Convenience sample of adult patients with chronic pain treated in a family medicine clinic | Self-selected for inclusion and self-report regarding duration of pain | Self-report evaluation of childhood trauma (sexual, physical, emotional abuse, and witnessing violence) [yes/no] | Self-Harm Inventory (Sansone et al., 1998) | 100% | 52.9% any trauma 11.8% sexual abuse 17.6% physical abuse 23.5% emotional abuse 47.0% witnessing violence | N/A | N/A (not reported; 27.8% endorsed a Hx of 5 or more types of SH) | N/A | Self-harm correlated moderately (though not significantly) and strongly with two measures of BPD (PDQ-R and DIB, respectively), strongly with somatic preoccupation, moderate-to-strongly (though not significantly) with number of types of child abuse, and moderately (though not significantly) with pain intensity. |

Note. All studies include assessment or description of patient chronic pain, trauma, and self-harm and utilize quantitative/empirical methodology. “Self-harm” includes suicidal self-injury, while “NSSI” only includes non-suicidal self-injury.

N study sample size, PTSD posttraumatic stress disorder, NSSI non-suicidal self-injury, ICD International Classification of Diseases, SH self-harm, Hx history, SI suicidal ideation, Dxd diagnosed, BPD borderline personality disorder, PDQ-R Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised, DIB Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines

Table 3.

Summary of reviewed case studies (k = 8)

| Year | Author(s) | Study type | Case composition | Type of chronic pain | Type of trauma | Type of self-harm | Primary implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Kuppilli et al | Single-case | 43-year-old woman with non-cancer somatic complaints of 19 years and opioid use of 13 years who presented to a public hospital in India for injection-related ulcers | Range of changing experience of pain, including in head, back, abdomen, and during urination and menstruation | Recent death of husband | Self-injection of pentazocine with resulting ulcers requiring surgery | Implies opiate use in response to chronic pain may produce chemical/psychological dependencies that give rise to self-damaging behavior in relation to further opiate acquisition and administration. Recent stressors, such as death of a loved one, may contribute to increased risk of such self-injurious behavior. |

| 2012 | Banke et al | Single-case | 40-year-old white male bodybuilder presenting to an orthopedic clinic who self-injected sesame seed oil into 20 muscle areas for 8 years for “muscle augmentation and shaping” | Persistent pain particularly in both upper arms lasting at least 3 years after septic surgery to reduce infection and remove unhealthy material | “The general history was free of trauma” | Self-injection of sesame seed oil with resulting swelling, inflammation, and particularly cystic scarring and infection in right arm requiring surgery | Example of chronic pain that may be the direct result of repeated NSSI. In this case, self-injury was motivated by secondary benefit (i.e., body enhancement) rather than for direct benefit of self-injury itself (e.g., emotion regulation). |

| 2011 | Kachramanoglou et al | Single-case | 17-year-old male adolescent who presented for rehabilitative treatment after a motor vehicle accident | Intermittent dull arm pain and sharp burning sensations in forearm lasting at least 14 months post-accident | Motor vehicle accident | Biting of nails and fingers of hand on injured arm resulting in irreversible loss of tissue and multiple hospitalizations | Highlights NSSI that may occur as a compulsive behavior directed towards body parts damaged in traumatic physical accident, possibly potentiated by history of related compulsive behavior (i.e., nail biting during adolescent years). Authors compare such behavior to autotomy seen in injured animals. |

| 2009 | Kapfhamer et al | Single-case | 38-year-old woman who presented to ER after self-injection of canine intranasal vaccine | Chronic back pain | Domestic abuse | Self-injection of three vials of “reconstituted canine intranasal kennel cough vaccine” into right forearm to “end the pain” | Evidence that limited acute emotion regulation capacity in conjunction with prior history of mood disorder, suicide attempt, and other risk factors such as chronic pain and domestic abuse may give rise to self-harm in the context of acute stressors related to physical health and capacity (e.g., “frustrat[ion] about her physical condition while walking her dogs”). It is unclear if patient’s injection was suicidal or non-suicidal in nature. |

| 2008 | Frost et al | Case series | Five adult patients (two women) with traumatic spinal cord injury with established relationship with authors employed at a rehabilitative medicine clinic | Three of five patients reported persistent pain; only one reported pain in injured limb | Motor vehicle accident; diving accident; fall of unknown traumatic severity; injury of unknown traumatic severity; complication of cervical disk surgery | Autophagia of digits in hand associated with impaired functioning due to spinal cord injury | Suggests that NSSI may function to stimulate parts of the body that have lost sensation due to physical injury. Reports that all patients engaged in nail biting prior to spinal cord injury, suggesting that pre-existing compulsive behavior may exacerbate onset of NSSI post-injury. |

| 1996 | Mailis | Case series | Four adult patients with chronic pain seen by the author, the director of a physical medicine and rehabilitation hospital division | Wallenberg’s syndrome; post-cardotomy pain syndrome; brachial plexus/nerve injury pain; complex regional pain syndrome | One patient (case 4) experienced a motor vehicle accident | Biting, scratching, and/or rubbing with resulting damage to skin or body, focused on part of body associated with dysesthesia associated with chronic pain/injury | Highlights link between post-injury/chronic pain NSSI and dysesthesia in targeted part of the body, implying that disruption of normal sensation (whether with increased or decreased pain response) in affected part of the body may contribute to self-injury in this part of the body. Evidence was found of increasing SIB with increasing pain in 3 of 4 patients. Authors note that depression, difficulty tolerating frustration, and social isolation occurred in 3 of 4 cases and personality disorder in one. No patient exhibited nail-biting prior to pain onset. |

| 1990 | Procacci & Maresca | Case series | Two adult male patients presenting to a pain clinic with brachial plexus injuries | Allodynia (and hyperpathia) in affected limb and hand | Motor vehicle accident | Biting of nails and fingers | Patients reported biting their nails and fingers in the middle of the night, producing pain and waking themselves from sleep. This behavior was successfully interrupted by wearing gloves at night. |

| 1989 | Ballard | Single-case | 23-year-old woman admitted to a general hospital after overdose on sedative medication | History of headaches since age 18 subsequent to a chronic “feeling of pressure” in patient’s head since age 15 | Denied an explicit trauma history, though patient noted she “had been shown little affection by her parents” and “had never been happy even as a child” | Superficial cuts on arms and scratching face as adolescent and again at age 22 after return of headache/pressure four years after lumbar puncture regimen at age 18 successfully eliminated these symptoms and NSSI | Authors suggest that intracranial hypertension may be an undiagnosed contributor to NSSI as well as the experience of headache, though no causal link is clear as both tension/headache and NSSI appeared and disappeared concurrently in the patient. However, patient did report that NSSI alleviated head tension/pain. |

Note. All studies include assessment or description of patient chronic pain, trauma (or lack thereof), and self-harm and utilize qualitative single-case or case series methodology. “Self-harm’ includes suicidal self-injury, while “NSSI” only includes non-suicidal self-injury. NSSI non-suicidal self-injury

Participant Characteristics

Empirical samples included study sizes ranging from 17 to 56,187 subjects with a median of 117 and a mean of 11,334. Participants were predominately women in four studies, and men in one study, with a median of 62% and a mean of 53% being women. Across all studies, age of subjects ranged from 41.7 to 57.2, with a median of 45 and a mean of 47 years. Case reports and series, which included 16 participants total, had a diverse age range including one adolescent case report [48]. Settings varied from individuals seen in emergency settings [49], veterans hospitals [41], and public/general hospitals [46, 50] to tertiary pain clinics [42, 44, 53], internal/family medicine clinics [43, 45], rehabilitation clinics [48, 51, 52], and orthopedic clinics [47]. Empirical studies primarily contained mixed chronic pain samples, while case studies focused on individuals with specific physical injuries or accidents (e.g., motor vehicle accident [48, 52, 53], medication-related physical insult [46, 49, 50]). Case studies were less likely to utilize comprehensive structured assessments of pain symptomology.

Trauma Characteristics

Trauma was assessed in empirical studies by semi-structured interview [42], medical record review [41], or self-report [43–45]. Case studies did not describe the form of trauma assessment, though most trauma information appeared to be gathered from unstructured clinical interview. Empirical reports evaluated lifetime trauma exposure [42], exposure to childhood trauma only [43–45], or posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis [41]. Two empirical studies reported specific rates of trauma [42, 43], with 12–19% reporting childhood sexual abuse, 18% childhood physical abuse, 23.5% childhood emotional abuse, and 9% adult domestic abuse. The prevalence of PTSD, 5.6%, was only available in one study [41], though notably this study included over 90% men and relied on PTSD diagnosis in the medical record. Trauma exposure was significantly associated with the number of pain disorders endorsed in one study, though the association varied by trauma type [45], and number of types of child abuse showed a small-to-moderate (r = .24), though non-significant, association with past-week pain intensity in a sample of 17 patients [43]. Of the 16 patients included in case reports, eleven endorsed exposure to some form of trauma or potentially traumatic event. These ranged from car/fall accidents [48, 51–53], to domestic violence [49], loss of a loved one [50], and medical complications [51]. Case studies indicated that patients presenting after physical traumas such as motor vehicle accidents and falls reported the onset of chronic pain subsequent to this trauma, while other forms of trauma (e.g., loss of a loved one) generally appeared causally independent of chronic pain.

Self-harm, NSSI, and Trauma in Chronic Pain Samples

Presence of self-harm or NSSI was assessed via clinical interviews [42], medical record review [41], or self-report evaluation using the Self-Harm Inventory [31] [43–45] in quantitative reports and via clinical interviews in all case studies. Rates of self-harm behavior varied widely from 1.5% when using retrospective diagnostic codes [41] to 25.4% when participants responded to direct questions [42], to as high as 52.1% on broad self-report measures [44]. In two separate studies, endorsement of using at least 5 self-harm behaviors was reported by approximately 20% of respondents [43, 45]. Only one empirical study differentiated NSSI from self-harm broadly [42], reporting a rate of 18.8% of participants endorsing a history of NSSI specifically. In this study, overdose on medication was the most common form of NSSI (46.9% of those engaging in NSSI), followed by cutting (30.6%).

The presence of self-harm was significantly associated with increased dosages of opiate treatment (1.24% of opiate maintainers vs 2.02% of opiate increasers reported self-harm) [41], borderline personality characteristics (r’s = .32 and .67) [43], and childhood abuse exposure [42, 44], but not adult domestic abuse [42]. One study also reported that suicidal self-harm (rather than NSSI) as well as suicidal ideation were not associated with childhood trauma [42]. Case studies tended to focus on detailed description and hypothesized explanations of self-injurious behavior, with nearly all reporting on NSSI in isolation, unlike in the quantitative research. The primary forms of NSSI reported in the case studies were biting nails and fingers [48, 51–53] and self-injection [47, 49, 50]. A number of case examples described a common chronological sequence of physical trauma contributing to chronic pain and/or dysesthesia, followed by NSSI [48, 51–53].

Discussion

As is clear from our review, very few studies have explored the relations among trauma, chronic pain, and self-harm, and only one has isolated NSSI in examining these associations empirically.

Thus, only limited speculation can be made regarding the ways in which these constructs interdigitate. The existing evidence suggests that in chronic pain populations, risk for NSSI seems particularly elevated in the context of a diversity of types of childhood trauma. Less is known regarding the associations between adult trauma or PTSD and self-harm, given little empirical research exploring these constructs specifically. However, numerous case studies assessing lifetime trauma and NSSI in patients with chronic pain provide some insight into several potential causal pathways linking these phenomena.

The Intersection of Self-Harm and Trauma in Chronic Pain

Our review highlights elevated rates of self-harm among individuals with chronic pain, with up to 50% of patients endorsing some form of self-harm [42, 44]. Of note, the definition of self-harm and NSSI was particularly inclusive in multiple reviewed studies [42–45], including a broad range of impulsive or reckless behaviors (e.g., substance/medication abuse, self-critical thinking, sexual impulsivity, distancing oneself from God) that extend beyond traditional definitions of intentional and immediate damage to one’s body [15, 54], though others have used an intermediate definition of NSSI that includes substance/medication overdose and stopping recommended medical treatments [30]. Nevertheless, 20% or more of patients endorsed a history of five or more self-harm-related behaviors across multiple studies [43, 45], which is substantial and necessitates further inquiry. Furthermore, when not including medication overdose among the types of self-harm, which has often not been considered a form of NSSI, results of the only study to specifically assess NSSI still showed a 10% prevalence rate of NSSI among adults with chronic pain [42]. This rate of NSSI is roughly double the general epidemiological rate of NSSI among adults, and comparable to other epidemiological findings of NSSI rates among both adolescents and adults with chronic pain [32–34].

The evidence to date highlights a potential unique relationship between self-harm and chronic pain. Specifically, patients asked to self-define their NSSI behavior reported medication overdose as the most common form of self-injury [42], comprising 46.9% of reported types of NSSI. In comparison, in a study assessing a range of self-harm behaviors among a sample with elevated rates of borderline personality disorder (a developmental disorder of self-regulation associated with high rates of NSSI [55]), cutting or scratching was the most common form of NSSI (68%), compared to drug overdose (11%) [30]. Prescription of opiate or other powerful, mood-altering medications to patients with chronic pain may inadvertently provide access to a common means of NSSI (alongside suicide attempts) among this population, emphasizing the importance of monitoring and assessing for abuse of medications prescribed to individuals with chronic pain (e.g., [56•]).

This review also revealed that childhood trauma—as well as number of types of child abuse [43]—may be a key feature associated with self-harm in chronic pain populations, with a three to fourfold increase in rates of childhood physical and sexual abuse among chronic pain patients who engage in NSSI [42]. These findings are corroborated by unpublished data from our recent work [2]: in a sample of 211 patients with chronic pain, we found associations between trauma in childhood—but not adulthood—and self-harm history. Childhood trauma has been identified as a distal risk factor for NSSI in the general population by altering views of the self or producing intense internal but difficult-to-express emotional states, resulting in the use of NSSI as an emotion regulation or communication tool [16••]. In the same vein, some individuals with chronic pain may already be at increased risk for NSSI due to the negative emotional correlates of persistent pain and a desire to express such internal states to others, exacerbated by traumatic life experiences.

On the other hand, the case studies reviewed here also indicate that NSSI may develop in response to an acute physical injury occurring in individuals with no prior history of self-harm. Thus, chronic pain and childhood trauma may interact to produce risk for NSSI as a self-regulatory behavior, and altered pain sensation after physical trauma may mediate NSSI as a response to dysesthesia. Further research on the function of self-harm is necessary in order to understand potentially distinct patient subpopulations. A particular focus on the timing of NSSI manifestation in relation to chronic pain onset and trauma exposure may elucidate causal links among these phenomena.

Incorporating the clinical insights highlighted in the set of qualitative case studies reviewed, a number of potential causal mechanisms may be proposed that explain the associations between trauma, pain, and NSSI. For instance, NSSI may result from an acute physical injury as a response to dysesthesia in the affected part of the body among individuals with no history of self-harm [52, 57, 58], though a history of compulsive behavior (e.g., nail biting) may exacerbate this pathway [48, 51]. Alternatively, experiencing trauma may tax intrinsic emotion regulation capacity and deteriorate self-regard [16••], leading to a reduced threshold for NSSI among individuals seeking regulatory strategies to alleviate the physical and psychological burden of chronic pain [50]. These hypotheses build on a core foundational clinical and empirical understanding that trauma, whether occurring in childhood or adulthood, functions as a precipitating factor for chronic pain and NSSI and suggest that they may be (1) mutually maintained, (2) causally linked in one direction or the other, (3) both traumatic sequelae that co-occur due to shared risk, or (4) simultaneously influenced by related psychological phenomena (e.g., borderline personality disorder).

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

This review provides several implications for assessment and intervention. First, as others have already argued [44], the clear links between childhood trauma and both chronic pain and NSSI indicate that assessing for childhood abuse and neglect as well as history of and current self-harm behavior is warranted by clinicians treating patients with chronic pain. Although adult physical trauma, such as accidents and injuries, is commonly assessed prior to chronic pain treatment, it is less common for childhood trauma to be assessed among these patients. Understanding the developmental context and environment insults that may have conferred risk for chronic pain, central sensitization, or self-harm behaviors (especially when these co-occur) may provide the clinician important context in which to understand their patient’s symptoms as well as collaborate on treatment planning together.

Related, risk of PTSD is elevated in chronic pain [59], and even more so in specific populations such as fibromyalgia (45–57% [60, 61]), interstitial cystitis (42% [3]), or chronic pelvic pain (31–36% [62, 63]). As individuals with PTSD are particularly vulnerable to self-harm behavior [22, 64], assessing for PTSD symptoms may be especially important. We recognize that fully evaluating patients for PTSD may not be feasible during a clinic visit, and patients are often hesitant to report trauma to medical providers [65]. Instead, we suggest using brief measures, such as in the publicly available 4-item primary care PTSD screening tool (PC-PTSD; [66]) or the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; [67]), allowing the provider to make appropriate referrals for further evaluation or trauma-informed treatment.

In terms of addressing the co-occurrence of NSSI and chronic pain among those who have experienced trauma, clinicians treating chronic pain conditions may do well to take note of evidence of non-suicidal self-injury (e.g., forearm scars or burn marks, damaged skin around extremities, medication usage inconsistent with prescribed dosages) and to carefully inquire of patients whether they have previously or are currently experiencing urges to harm themselves in any way. Such line of inquiry can be intertwined with standardized risk assessment, such as when assessing for suicidal ideation or intent. Self-harm behaviors are unfortunately highly stigmatized among both the wider community and within the healthcare system itself [68•], requiring clinicians to take a gentle but straightforward approach to assessing for such behaviors as well as a demeanor of caring curiosity—rather than criticism or panic—when patients endorse self-injurious urges or behaviors.

Psychotherapists may also benefit from training in interventions that account for the emotional sequelae of trauma and the self-regulating function of NSSI, particularly when working with patients with chronic pain, or may need to refer their patients to providers with such training. Several treatments exist that are putatively well-suited to the overlap among these issues, such as Emotional Awareness and Expression Therapy [37•], which helps patients identify affect avoidance, express emotions directly, and improve interpersonal communication. Similarly, facilitating emotion regulation when conducting exposure therapy has also been shown to benefit some pain outcomes for pain patients with elevated anxiety or depression [69]. Some preliminary evidence suggests that trauma-focused psychotherapies, including Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, may benefit patients with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD [70]. Other trauma informed treatments that are not specifically tailored to chronic pain but focus on enhancing emotion regulation and addressing self-regulation and other psychological mechanisms relevant to both chronic pain and self-harm, include dialectical behavior therapy [71], which has been applied to PTSD in patients with NSSI [72], and “Seeking Safety,” a treatment for comorbid PTSD and substance abuse [73]. The focus on facilitating emotion regulation strategies may both function to alter patients’ responses to existing elevations in pain intensity, as well as downregulate pain intensity, which may replace the function of NSSI among these individuals. However, data on any of these modalities simultaneously treating both chronic pain and NSSI, particularly in the context of trauma, are lacking.

Future Directions

As is evident in our review of the literature, a number of avenues for future research exist:

Development of a putative framework that integrates across the three domains of trauma, chronic pain, and NSSI and serves as a foundation for future research and clinical practice.

Prospective, longitudinal research that may allow for causal claims regarding the role of trauma in the co-occurrence of chronic pain and NSSI.

Exploration of the types and pattern of NSSI among patients with chronic pain (e.g., overdose vs. cutting vs. biting) and the specific function(s) of NSSI in this population.

Examination of the relationship between NSSI and patient-level factors such as emotional distress, trauma and PTSD, personality structure, and demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, and race).

Empirically supported treatments that address NSSI among patients with chronic pain, especially that account for the contributing presence of childhood and/or adult trauma.

Of interest in future work is to examine the function of manifesting acute pain via NSSI and its impact on pain processing. In other populations, NSSI (e.g., cutting) has been associated with decreased pain intensity, increased pain tolerance, and increased pain threshold, despite occurring alongside elevated rates of chronic pain (i.e., a “pain paradox” [74, 75]). Some limited recent evidence has indicated this paradox may also occur among patients with chronic pain [76•], yet how NSSI translates to acute vs. chronic pain experiencing in this population is not understood. Related research involving pain and emotion regulation via endogenous (e.g., released by NSSI) versus exogenous (e.g., medication-induced) opioids is also warranted [77, 78].

Conclusions

Our systematic review of the extant literature on trauma and self-harm in chronic pain provides limited initial evidence of the importance of trauma in the display of NSSI in this population. Clinicians should consider assessing for childhood trauma and NSSI among patients with chronic pain and tailor treatment approaches accordingly. Future research exploring the function and causal links among these phenomena is needed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the American Psychological Association Society of Clinical Psychology (Division 12) Research Assistance Task Force for facilitating this work.

Funding

This manuscript was prepared with support from the Vanderbilt Patient Centered Outcomes Research Education and Training Initiative and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 6K12HS022990-04) and by Vanderbilt University Medical Center CTSA award No. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Finestone HM, Stenn P, Davies F, Stalker C, Fry R, Koumanis J. Chronic pain and health care utilization in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKernan LC, Johnson BN, Crofford LJ, Lumley MA, Bruehl S, Cheavens JS (2019) Posttraumatic stress symptoms mediate the effects of trauma exposure on clinical indicators of central sensitization in patients with chronic pain. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKernan LC, Johnson BN, Reynolds WS, Williams DA, Cheavens JS, Dmochowski RR, Crofford LJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: relationship to patient phenotype and clinical practice implications. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:353–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicol AL, Sieberg CB, Clauw DJ, Hassett AL, Moser SE, Brummett CM. The association between a history of lifetime traumatic events and pain severity, physical function, and affective distress in patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2016;17:1334–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwoli L, Platt JM, Basu A, Williams DR, Stein DJ, Koenen KC. Associations between lifetime potentially traumatic events and chronic physical conditions in the South African Stress and Health Survey: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tietjen GE, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Recalled maltreatment, migraine, and tension-type headache: results of the AMPP study. Neurology. 2015;84:132–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachs-Ericsson NJ, Sheffler JL, Stanley IH, Piazza JR, Preacher KJ. When emotional pain becomes physical: adverse childhood experiences, pain, and the role of mood and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73:1403–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis DA, Luecken LJ, Zautra AJ. Are reports of childhood abuse related to the experience of chronic pain in adulthood?: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane RD, Anderson FS, Smith R. Biased competition favoring physical over emotional pain: a possible explanation for the link between early adversity and chronic pain. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afari N, Ahumada SM, Wright LJ, Mostoufi S, Golnari G, Reis V, Cuneo JG. Psychological trauma and functional somatic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck JG, Clapp JD. A different kind of comorbidity: understanding posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2011;3:101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD. An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40:397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:857–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.••. Lumley MA, Schubiner H. Psychological therapy for centralized pain: an integrative assessment and treatment model. Psychosom Med. 2019;81:114. Provides a summary and overview of the literature base undergirding emotional awareness and expression therapy, an effective treatment for central sensitization-related pain disorders that may be particularly suited for patients with a history of trauma, PTSD symptoms, and NSSI (see also Lumley & Schubiner, 2019b).

- 15.Nock MK, Favazza AR (2009) Nonsuicidal self-injury: definition and classification. In: Underst. Nonsuicidal Self-Inj. Orig. Assess. Treat American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US, pp 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.••. Hooley JM, Franklin JC. Why do people hurt themselves? A new conceptual model of nonsuicidal self-injury. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6:428–51. Proposes the “benefits and barriers” model of NSSI that highlights both the potential role of childhood maltreatment in reducing the threshold of engaging in NSSI and various regulatory and/or communicative functions of NSSI behavior.

- 17.Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1981–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, John NJS. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:273–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bresin K, Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu RT, Scopelliti KM, Pittman SK, Zamora AS. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.In-Albon T, Ruf C, Schmid M (2013) Proposed diagnostic criteria for the DSM-5 of nonsuicidal self-injury in female adolescents: diagnostic and clinical correlates. Psychiatry J 2013:e159208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cipriano A, Cella S, Cotrufo P. Nonsuicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2017. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fliege H, Lee J-R, Grimm A, Klapp BF. Risk factors and correlates of deliberate self-harm behavior: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:477–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bornovalova MA, Tull MT, Gratz KL, Levy R, Lejuez CW. Extending models of deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts to substance users: exploring the roles of childhood abuse, posttraumatic stress, and difficulties controlling impulsive behavior when distressed. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2011;3:349–59. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Favazza AR (2011) Bodies under siege: self-mutilation, non-suicidal self-injury, and body modification in culture and psychiatry. JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, Nock MK. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016;46:225–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreitman N, Philip A, Greer S, Bagley C. Parasuicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;116:460–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diekstra RF. The epidemiology of suicide and parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, Wagner A. Suicide attempt self-injury interview (SASII): development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Sansone LA. The self-harm inventory (SHI): development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54:973–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prior JA, Paskins Z, Whittle R, Abdul-Sultan A, Chew-Graham CA, Muller S, Bajpai R, Shepherd TA, Sumathipala A, Mallen CD. Rheumatic conditions as risk factors for self-harm: a retrospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2021;73:130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webb RT, Kontopantelis E, Doran T, Qin P, Creed F, Kapur N. Risk of self-harm in physically ill patients in UK primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73:92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig J, Oelkers-Ax R, Parzer P, Haffner J, Brunner R, Resch F, Kaess M (2015) The association of self-injurious behaviour and suicide attempts with recurrent idiopathic pain in adolescents: evidence from a population-based study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singhal A, Ross J, Seminog O, Hawton K, Goldacre MJ. Risk of self-harm and suicide in people with specific psychiatric and physical disorders: comparisons between disorders using English national record linkage. J R Soc Med. 2014;107:194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lumley MA, Cohen JL, Borszcz GS, Cano A, Radcliffe AM, Porter LS, Schubiner H, Keefe FJ. Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:942–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.•. Lumley MA, Schubiner H. Emotional awareness and expression therapy for chronic pain: rationale, principles and techniques, evidence, and critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21:30. Outlines a comprehensive approach to assessing and treating central sensitization-related pain disorders that incorporates a focus on emotion regulation and may be particularly suited for patients with a history of trauma, PTSD symptoms, and NSSI.

- 38.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, the PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647–g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. The ICD-11 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: Author; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes CJ, Krebs EE, Hudson T, Brown J, Li C, Martin BC. Impact of opioid dose escalation on the development of substance use disorders, accidents, self-inflicted injuries, opioid overdoses and alcohol and non-opioid drug-related overdoses: a retrospective cohort study. Addiction. 2020;115:1098–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okifuji A, Benham B. Suicidal and self-harm behaviors in chronic pain patients. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2011;16:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sansone RA, Whitecar P, Meier BP, Murry A. The prevalence of borderline personality among primary care patients with chronic pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sansone RA, Sinclair JD, Wiederman MW. Childhood trauma and self-harm behavior among chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2009;13:238–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sansone RA, Pole M, Dakroub H, Butler M. Childhood trauma, borderline personality symptomatology, and psychophysiological and pain disorders in adulthood. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballard CG. Benign intracranial hypertension and repeated self-mutilation. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:570–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banke IJ, Prodinger PM, Waldt S, Weirich G, Holzapfel BM, Gradinger R, Rechl H. Irreversible muscle damage in bodybuilding due to long-term intramuscular oil injection. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kachramanoglou C, Carlstedt T, Koltzenburg M, Choi D. Self-mutilation in patients after nerve injury may not be due to deafferentation pain: a case report. Pain Med. 2011;12:1644–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kapfhamer J, Russeth K, Heinrich T, Heinrich K. Subcutaneous injection of intranasal canine kennel cough vaccine. Psychosom J Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2009;50:180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuppilli PP, Bhad R, Rao R, Dayal P, Ambekar A. Misuse of prescription opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. Natl Med J India. 2015;28:284–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frost FS, Mukkamala S, Covington E. Self-inflicted finger injury in individuals with spinal cord injury: an analysis of 5 cases. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mailis A Compulsive targeted self-injurious behaviour in humans with neuropathic pain: a counterpart of animal autotomy? Four case reports and literature review. Pain. 1996;64:569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Procacci P, Maresca M. Autotomy Pain. 1990;43:394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klonsky ED, Muehlenkamp JJ, Lewis SP, Walsh B (2011) Non-suicidal self-injury. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reichl C, Kaess M. Self-harm in the context of borderline personality disorder. Curr Opin Psychol. 2021;37:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.•. Siste K, Nugraheni P, Christian H, Suryani E, Firdaus KK. Prescription drug misuse in adolescents and young adults: an emerging issue as a health problem. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32:320–7. Provides an overview and call to action to address the growing pandemic of opiate and other medication misuse among adolescents and young adults with implications for medication treatment among individuals with chronic pain.

- 57.Al-Qattan MM. Self-mutilation in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg. 1999;24:547–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCann ME, Waters P, Goumnerova LC, Berde C. Self-mutilation in young children following brachial plexus birth injury. Pain. 2004;110:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siqveland J, Hussain A, Lindstrøm JC, Ruud T, Hauff E. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with chronic pain: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2017. 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen H, Neumann L, Haiman Y, Matar MA, Press J, Buskila D. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia patients: overlapping syndromes or post-traumatic fibromyalgia syndrome? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Häuser W, Galek A, Erbslöh-Möller B, et al. (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia syndrome: prevalence, temporal relationship between posttraumatic stress and fibromyalgia symptoms, and impact on clinical outcome. PAIN® 154:1216–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meltzer-Brody S, Leserman J, Zolnoun D, Steege J, Green E, Teich A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:902–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poleshuck EL, Gamble SA, Bellenger K, Lu N, Tu X, Sörensen S, Giles DE, Talbot NL. Randomized controlled trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus enhanced treatment as usual for women with co-occurring depression and pelvic pain. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turner BJ, Dixon-Gordon KL, Austin SB, Rodriguez MA, Zachary Rosenthal M, Chapman AL. Non-suicidal self-injury with and without borderline personality disorder: differences in self-injury and diagnostic comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldstein HB, Safaeian P, Garrod K, Finamore PS, Kellogg-Spadt S, Whitmore KE. Depression, abuse and its relationship to interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecology J. 2008;19:1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, Thrailkill A, Gusman FD, Sheikh JI. The primary care PTSD screen (PC–PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2004;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.•. Gurung K. Bodywork: Self-harm, trauma, and embodied expressions of pain. Arts Humanit High Educ. 2018;17:32–47. Ideographic and client-centered account of the causes, functions, cultural context, and stigmatization of NSSI.

- 69.Boersma K, Södermark M, Hesser H, Flink IK, Gerdle B, Linton SJ. Efficacy of a transdiagnostic emotion–focused exposure treatment for chronic pain patients with comorbid anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2019;160:1708–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tesarz J, Wicking M, Bernardy K, Seidler GH. EMDR therapy’s efficacy in the treatment of pain. J EMDR Pract Res. 2019;13:337–44. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harned MS, Schmidt SC. Integrating post-traumatic stress disorder treatment into dialectical behaviour therapy: clinical application and implementation of the DBT prolonged exposure protocol. In: Oxf. New York, NY, US: Handb. Dialect. Behav. Ther Oxford University Press; 2019. p. 797–814. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Najavits LM. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse: clinical guidelines for implementing Seeking Safety therapy. Alcohol Treat Q. 2004;22:43–62. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carpenter RW, Trull TJ. The pain paradox: borderline personality disorder features, self-harm history, and the experience of pain. Personal Disord Theory Res Treat. 2015;6:141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Borderline personality and the pain paradox. Psychiatry Edgmont. 2007;4:40–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.•. Johnson BN, Lumley MA, Cheavens JS, McKernan LC (2020) Exploring the links among borderline personality disorder symptoms, trauma, and pain in patients with chronic pain disorders. J Psychosom Res 135:110164. Recent correlational study of patients with chronic pain using a multidimensional assessment of pain experiencing and central sensitization with implications for the subset of patients at risk for NSSI in terms of chronic vs acute pain experience and the role of trauma.

- 77.Kirtley OJ, O’Carroll RE, O’Connor RC. Pain and self-harm: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:347–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ducasse D, Courtet P, Olié E. Physical and social pains in borderline disorder and neuroanatomical correlates: a systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]