Objectives

This is a protocol for a Cochrane Review (intervention). The objectives are as follows:

To compare the efficacy and safety of topical anti‐inflammatory treatments for reducing eczema symptoms or signs or improving eczema‐related quality of life in children and adults with eczema, by undertaking a network meta‐analysis.

To provide a clinically useful ranking of these treatments according to their efficacy and safety.

Background

Description of the condition

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis or atopic eczema, is a common skin disease, affecting up to 20% of young children and 5% of adults, increasing slightly in older age (de Lusignan 2021; Hay 2014; Williams 2008). It is a chronic, fluctuating condition that varies in severity and can be divided into mild, moderate, and severe forms. In mild eczema, individuals may have only occasional localised patches of inflamed skin that cause minimal symptoms, but in severe eczema, involvement can be extensive with widespread erythema, excoriations and chronic skin changes such as lichenification.

Eczema can have a substantial impact on quality of life and psychosocial domains (social, academic, and occupational) through persistent itch and the stigma associated with having visibly affected skin (Carroll 2005; Chamlin 2004; Drucker 2017; Lewis‐Jones 2006). The impact on quality of life can exceed that reported in other chronic conditions, such as asthma and diabetes, especially when eczema is severe or affects readily visible areas (Beattie 2006; Drucker 2017; Kemp 2003). Eczema also causes an economic burden, and in the USA alone, the direct costs of eczema are estimated to be in excess of USD (US dollar) 1 billion per year (Drucker 2017). Costs also affect people with eczema and their families, including expenses such as buying moisturisers or bath oils not available on prescription, buying special clothing, and taking time off work to care for a child with eczema (Carroll 2005).

Description of the intervention

While eczema often improves around puberty, a significant proportion of individuals still require treatment in adult life (Abuabara 2018), and in others, eczema does not start until adulthood. Eczema is managed with long‐term treatments. For the majority of people, treatment is topical. Emollients (also called moisturisers) are a mainstay of eczema treatment, but predominantly have a preventative role through hydrating the skin and improving the skin barrier; they are inadequate to reduce inflammation, apart from in very mild cases. To treat actively inflamed areas, topical anti‐inflammatory agents are needed (NICE 2007).

Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the first‐line topical anti‐inflammatory treatment for eczema (NICE 2007; Wollenberg 2020). TCS are typically applied once or twice daily to actively inflamed areas of skin for 7‐14 days, or until resolution. 'Weekend therapy' (i.e. the proactive regular twice‐weekly application of treatment) is also used, and can improve long‐term control in people with frequent flares (Williams 2004). TCS preparations can be classified into different potency groups based on vasoconstriction assays (Eichenfield 2014), and different potencies are used for treatment depending on the individual's age, site of application, and disease severity. Antimicrobials and salicylic acid may also be added to TCS preparations. TCS agents have a very well‐established safety profile as they have been used extensively since the 1950s. Despite this, research suggests that many people with eczema and their carers have a number of concerns about TCS (Teasdale 2021), including skin thinning (Charman 2000). Although such adverse effects are typically associated with inappropriate use of more potent TCS agents (Charman 2000; Hajar 2015), people with eczema and their carers also have concerns when using mildly potent agents (Bos 2019; Charman 2000). These concerns can have important implications for treatment adherence and consequently disease control.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) have been available since 2000. Current TCI agents in use include tacrolimus 0.03% ointment, tacrolimus 0.1% ointment, and pimecrolimus 1% cream. Tacrolimus 0.03% ointment and pimecrolimus 1% cream are indicated for use in individuals aged two years or older, and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment is approved in those aged 16 years or more (Wollenberg 2020). However, TCI are commonly used in children aged under two years, and this is supported by guideline recommendations (Eichenfield 2014; Wollenberg 2020). American Academy of Dermatology guidelines suggest that 1) TCI can be used for both acute and chronic treatment of eczema and that 2) TCI can be preferable to TCS when there is recalcitrance to steroids, steroid‐induced atrophy, long‐term uninterrupted TCS use, and when treatment is needed at sensitive sites (e.g. facial, anogenital, or skin fold) (Eichenfield 2014). The European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD) recommends first‐line use of TCI at sensitive sites (with a preference for pimecrolimus in mild eczema and tacrolimus in moderate and severe eczema) and for long‐term topical treatment (Wollenberg 2020). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that TCI are an option for the second‐line treatment of moderate‐to‐severe eczema in individuals aged two years or over “that has not been controlled by TCS or where there is a serious risk of important adverse effects from further TCS use, particularly irreversible skin atrophy” (NICE 2007).

While TCIs are often promoted as being ‘steroid‐sparing’, there is limited evidence that they are any safer. In a 2016 review, more than two‐thirds of all TCI studies had not used any active comparator (Wilkes 2016), and is the only long‐term head‐to‐head trial comparing TCI against mild potency TCS, these agents were similarly safe and effective (Sigurgeirsson 2015). A 2015 Cochrane Review found that serious adverse events were rare for both TCI and TCS (Cury Martins 2015). The most common adverse effects of TCI were local tolerability issues, such as burning or stinging on application (Cury Martins 2015). A black‐box warning for theoretical carcinogenicity also exists for TCI, based upon postmarketing case reports of skin cancer and lymphoma. This risk of carcinogenicity is controversial as observational data has suggested no increased risk of keratinocyte carcinoma (Asgari 2020), lymphoma (in vitiligo patients; Ju 2021), and cancer overall (Paller 2020), but a recent meta‐analysis reported a small increased risk of lymphoma (Lam 2021). TCI agents cost approximately 10 times more than TCS per gram, and prescription costs of TCI for NHS England increased from GBP (pounds sterling) 3.7 million in 2004 to GBP 7.7 million in 2019 (NHS Digital 2019). The increasing prescribing rates of higher‐cost TCI are difficult to justify in the absence of comparative data showing improved efficacy or safety compared with TCS.

Expenditure on topical treatments for eczema may rise further as new, more costly topical anti‐inflammatory treatments come to market. A topical phosphodiesterase‐4 (PDE‐4) inhibitor, crisaborole, was licensed in the USA in 2016 and in the EU in 2020. More topical agents are likely to be approved soon, including Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, such as tofacitinib and delgocitinib (Bissonnette 2016; Dhillon 2020), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor activators, such as tapinarof (Paller 2021). Reported reasons for developing new topical treatments include existing treatments having local tolerability issues, restrictions for use on sensitive skin areas, or insufficient efficacy. However, trials of new topical therapeutics have generally not made direct comparisons to available treatments to allow efficacy and safety to be compared, so it cannot be determined whether new topical treatments meet this envisioned treatment need. Establishing whether newly approved agents are more effective (including the speed and duration of action) or safer than TCS and TCI will be crucial for clinicians and people with eczema to make informed treatment decisions and to best use the finite healthcare resources available.

How the intervention might work

The discussed agents are all topical anti‐inflammatory agents that reduce pro‐inflammatory cytokine production. These cytokines are molecules secreted by cells of the immune system which escalate immune responses, so reducing them leads to improved appearance of the skin and reduced itch. Topical agents also have favourable adverse effect profiles compared to systemic immunosuppressants and do not need regular monitoring blood tests. Topical agents are thus a cornerstone of eczema treatment plans.

TCS have a broad anti‐inflammatory action. They bind to glucocorticoid intracellular receptors and reduce levels of cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 1, IL‐2 and interferon (IFN)‐γ (Ahluwalia 1998). TCS also cause vasoconstriction (reduced blood flow) in the affected skin (Altura 1966). At sensitive sites such as the face, neck, and groin, TCS are typically limited to mild or moderate potency to reduce the risk of adverse effects.

TCI inhibit the enzyme calcineurin, which has the effect of decreasing T‐cell proliferation and the production of cytokines including IL‐2, IL‐3, IL‐4, IL‐12, TNF, and IFN‐γ (Cury Martins 2015). They have also been demonstrated to affect mast cell activation and decrease the number and co‐stimulatory ability of dendritic cells in the epidermis (Eichenfield 2014).

PDE‐4 inhibitors inhibit the enzyme PDE‐4, which leads to a decrease in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels (Zebda 2018). PDE‐4 activity is increased in circulating inflammatory cells of people with eczema, and inhibition of PDE‐4 in monocytes in vitro leads to reduced release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (Paller 2016).

JAK inhibitors inhibit JAK‐STAT signalling. There are 4 JAKs ‐ JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase (TYK) ‐ which are associated with type I and type II cytokine receptors. JAK is activated when these cytokine receptors are bound by their ligands, which comprise more than 60 cytokines and growth factors (Howell 2019). JAK then activates small molecules in the cytoplasm, which move to the nucleus and bind to DNA in order to alter gene transcription. These small molecules in the cytoplasm are called STATs due to their function ('Signal Transducers and Activator of Transcription') and speed of action ('stat' effect) (Stark 2012). Inhibition of the pathway can have anti‐inflammatory effects. For example, at least 90% of IL‐2 receptor signalling is JAK‐dependent (Schwartz 2017).

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a cytosolic ligand‐activated transcription factor that can be activated by various different molecules. It is widely expressed in the skin and plays an important role as a critical regulator of innate and adaptive immune responses, impacting the balance of Th17 and regulatory T cells (Smith 2017) and modulating gene expression important for skin barrier proteins, such as filaggrin, hornerin, and involucrin (Smith 2017). Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor is thus a target for new drugs, such as tapinarof (Smith 2017), and is also one of the modes of action of coal tar, which can be used in inflammatory skin diseases.

Why it is important to do this review

A Cochrane Skin prioritisation process in 2017, which included the involvement of people with eczema, identified ‘network meta‐analysis of topical anti‐inflammatory treatments for treating eczema’ as a key priority for a Cochrane Skin review (Presley 2019). This research question was prioritised because there is currently inadequate evidence to guide treatment decisions for topical anti‐inflammatory agents in eczema. Most new topical therapies are only compared against vehicle (a carrier system for an active treatment, which can also be used on its own as an emollient). This makes it very difficult for health care professionals and people with eczema to make a judgement on how the new treatment compares with existing active treatment in terms of benefits and potential harms and cost. The relative absence of reliable comparative clinical trial data means that treatment decisions when using topical anti‐inflammatory products for eczema are not evidence‐based.

Defining the most effective and safest topical treatments would ensure that resources are best allocated in eczema management. Commencing safe, effective topical therapy may also reduce the need for repeat primary care visits and secondary care referrals resulting from uncontrolled disease, an inability to start a certain medication, or a lack of confidence in the safety profile of certain medications.

A well‐conducted network meta‐analysis (NMA) is the best method to make direct and indirect comparisons between the many treatments available for eczema. Our review is especially timely due to the large number of new therapeutics emerging in this area and, without undertaking this planned work, there will likely be increasing confusion surrounding the best topical treatment for eczema, and potentially an associated increase in prescription costs without a positive impact on patient outcomes.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of topical anti‐inflammatory treatments for reducing eczema symptoms or signs or improving eczema‐related quality of life in children and adults with eczema, by undertaking a network meta‐analysis.

To provide a clinically useful ranking of these treatments according to their efficacy and safety.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We will include randomised controlled trials (RCTs), where individuals or groups are randomised. We will exclude trials that do not state that they are randomised, along with trials that are explicitly quasi‐randomised or non‐randomised designs. We will include the first phase of cross‐over trials (due to the risk of carry‐over effects to subsequent periods), cluster‐randomised trials and within‐participant trials. We will include trials where participants might be equally likely to receive alternative treatments, so that the transitivity assumption is not violated.

Types of participants

We will include trials of participants with a clinical diagnosis of eczema established using diagnostic criteria for eczema (or a modified version of such criteria) or diagnosis by a healthcare professional. We will not include participants with clinically infected eczema. There will be no restrictions on age, sex, ethnicity, or disease severity.

We will not include specific forms of eczema that are not atopic eczema, such as irritant contact eczema, allergic contact eczema, hand eczema, discoid eczema, asteatotic eczema, frictional eczema, stasis eczema, photosensitive eczema, and seborrhoeic eczema. If there are trials that include both eligible and non‐eligible participants (e.g. where some participants have eczema but others have irritant contact eczema), we will only include the trial if data on eligible participants with eczema are available separately.

Types of interventions

The intervention is topical anti‐inflammatory treatments. We will include the following interventions.

Topical corticosteroids (TCS), including combinations with antimicrobials (with the caveat that studies where eligibility is limited to clinically infected eczema will not be included) or salicylic acid. We will group TCS by potency (i.e. mild, moderate, potent, and very potent).

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI), such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.

Topical phosphodiesterase IV (PDE‐4) inhibitors, such as crisaborole.

Topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib or delgocitinib.

Topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) activators, such as tapinarof.

Any other well‐characterised novel anti‐inflammatory treatments.

In general, we expect most eligible interventions to be listed in the British National Formulary (BNF) as suitable products for treating eczema, but we will also include products not included in the BNF if they are clinically relevant. To ensure our review is relevant and focused, we will not include trials of historic topical therapies that are no longer used worldwide for managing eczema (such as coal tar), with the exception of trials of discontinued TCS for which potency of the TCS preparation can be inferred.

As we are assessing topical anti‐inflammatories, we will not include trials assessing: emollients alone, topical antibiotics alone, complementary therapies, topical probiotics, bandaging/wet wraps, systemic treatments, lasers, and phototherapy. We will also not include trials where systemic anti‐inflammatory treatments such as dupilumab, methotrexate, ciclosporin, corticosteroids, or phototherapy are used in combination with topical anti‐inflammatory agents. We will exclude these because the primary mechanism of action is not anti‐inflammatory, or because the treatment is not topically applied. We will include trials where participants in both intervention and comparator groups are using oral antihistamines, as these are not thought to be effective treatments for eczema.

In general, we are most interested in standard, licensed treatment regimens, such as once‐ or twice‐daily application of topical anti‐inflammatory cream, gel, lotion, or ointment to affected skin. We will pool once‐ or twice‐daily frequency of application and variations to duration of treatment for meta‐analysis. We will exclude trials where anti‐inflammatory treatments are used differently to standard licensed recommendations (e.g. initiated at less than once per day or more than twice per day for TCS and TCI) or for durations of less than one week. Treatment regimens which start with a standard regimen as per licensed recommendations, but then reduce to less frequent application after the initial daily treatment period, will still be included in the review, but the variations in treatment regimens used may impact the Confidence In Network Meta‐Analysis (CINeMA) certainty of evidence assessments.

We will include trials using the following comparators: different topical anti‐inflammatory treatments, placebo/vehicle/emollient, or no treatment. We will not include trials where the comparator is the same topical treatment but with a different method of application, as this has been evaluated for TCS in a separate Cochrane Review (Lax 2022). In the NMA, we will use a single control node of 'placebo/vehicle/emollient'. We will also include 'no treatment' as a separate node, but if trials using 'no treatment' allow emollient in both arms of the trial, we will include the control group in the 'placebo/vehicle/emollient' node.

Classifications of potencies of TCS vary between different countries. To standardise potency classifications of TCS in our study, we will use a classification we established as part of a separate Cochrane Review (mild, moderate, potent, or very potent ‐ see Table 1) (Lax 2022). In brief, we prioritise the potency classification used in the BNF; followed by the WHO Classification 2018; and, if neither source assigned a potency, we will consider relevant guidelines, advice from clinicians in the relevant country, and publicly available trial documents. For TCI, we will have different nodes for different potencies of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus. For other drug classes, we will take a similar approach, unless the potency classification of different concentrations of the same pharmacological agent is not known to differ. We will also undertake sensitivity analyses in which we will use an alternative TCS potency classification, and in which we use a more pooled approach of potency classification.

1. Classification of topical corticosteroid potency.

| Drug Name | Strength | Preparation | Generation | Potency | Source | Notes |

| alclometasone dipropionate | 0.05% | ointment | no | moderate | British National Formulary 2010 | |

| alclometasone dipropionate | 0.05% | cream | no | moderate | British National Formulary 2010 | |

| alclometasone dipropionate | ‐ | ‐ | no | moderate | inferred from British National Formulary 2010 | 0.05% is moderate ‐ no other strengths in the classification. |

| betamethasone 17‐valerate | 0.1% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| betamethasone dipropionate | 0.05% | cream | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| betamethasone dipropionate | 0.05% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| betamethasone dipropionate | ‐ | cream | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | 0.05% is potent. |

| betamethasone valerate | ‐ | ‐ | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Assume a standard preparation unless specified, therefore potent. |

| betamethasone valerate | 0.1% | cream | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| betamethasone valerate | 0.12% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| betamethasone valerate | 0.1% | fatty ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | Other preparations are potent at this strength. |

| betamethasone valerate | ‐ | cream | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Although 0.025% is moderate, assume no dilution from the standard unless specified, therefore potent. |

| betamethasone valerate | ‐ | ointment | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Although 0.025% is moderate, assume no dilution from the standard unless specified, therefore potent. |

| clobetasol propionate | 0.05% | cream | no | very potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| clobetasol propionate | 0.05% | ointment | no | very potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| clobetasone | 0.05% | cream | no | moderate | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | Not listed in any other charts without the salt; assume moderate. |

| clobetasone 17‐butyrate | 0.05% | lotion | no | moderate | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Lotion not listed, therefore assume moderate as for other preparations. |

| clobetasone butyrate | 0.05% | cream | no | moderate | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| clobetasone butyrate | 0.05% | ointment | no | moderate | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| clobetasone butyrate | ‐ | cream | no | moderate | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | No strength given so assume moderate unless specified. |

| clocortolone pivalate | 0.1% | cream | no | moderate | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | In National Psoriasis Foundation (USA) moderate as 0.1% cream. Clocortolone is moderate in European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines without strength or salt. |

| desonide | 0.05% | ‐ | no | mild | WHO Classification 2018 | Assume cream formulation. |

| desonide | 0.05% | cream | no | mild | WHO Classification 2018 | |

| desonide | 0.1% | micronized cream | no | mild | WHO Classification 2018 | Assume as cream formulation, therefore mild. |

| desonide | 0.1% | ointment | no | moderate | inferred from Resource Clinical (USA) | Information for 0.05%, therefore moderate as it's a higher strength ointment. |

| desonide | 0.05% | lotion | no | mild | inferred from WHO Classification 2018 | Assuming mild as for the cream. |

| desonide | 0.05% | ointment | no | moderate | Resource Clinical (USA) | Ointment appears in one of the USA charts only as moderate. |

| desonide | 0.1% | cream | no | moderate | inferred from WHO Classification 2018 | Assuming moderate to be consistent with ointment. |

| diflorasone diacetate | 0.05% | cream | no | moderate | WHO Classification 2018 | |

| diflorasone diacetate | 0.05% | ointment | no | very potent | WHO Classification 2018 | |

| diflucortolone valerate | 0.1% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2015 | |

| diflucortolone valerate | 0.1% | water/oil emulsion | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assume potent as for the ointment. |

| difluorocortolone valerianate | 0.1% | cream | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assume as for diflucortolone valerate 0.1% cream which is potent. |

| fluclorolone acetonide | ‐ | cream | no | potent | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | Fluclorolone unspecified is potent, but no salt, preparation or % given. |

| fluclorolone acetonide | ‐ | ointment | no | potent | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | Fluclorolone unspecified is potent, but no salt, preparation or % given. |

| flumethasone pivalate | 0.02% | cream | no | mild | Kim 2015 | Not listed in any of the other charts. |

| flumethasone pivalate | 0.2% | ointment | no | moderate | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | 10 times strength; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines states moderate where no strength is specified. |

| fluocinolone acetonide | 0.025% | cream | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| fluocinolone acetonide | 0.01% | cream | no | moderate | British Association of Dermatologists 2015 | |

| fluocinolone acetonide | 0.025% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| fluocinonide | 0.1% | cream | no | very potent | National Psoriasis Foundation (USA) | |

| fluocinonide | 0.05% | cream | no | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| fluocinonide | ‐ | Non‐aqueous synthetic base | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | No strengths given, but 0.05% potent in British National Formulary 2018 for cream and ointment preparations. |

| fluocortin butylester | 0.75% | cream | no | mild | Kim 2015 | Not listed in any of the other charts. |

| fluocortolone | 0.2% | ‐ | no | moderate | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assume moderate as for 0.25% |

| fluocortolone | 0.5% | ointment | no | moderate | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assume moderate as for 0.25% |

| fluocortolone/fluocortolone caproate | 0.25% | water/oil emulsion | no | moderate | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | |

| fluocortolone/fluocortolone caproate | 0.25% | ointment | no | moderate | British National Formulary 2015 | |

| fluprednidene‐21‐acetate | 0.1% | cream | no | moderate | inferred from European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | Fluprednidene in European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines as moderate (no % given). |

| flurandrenolone acetonide | 0.05% | ointment | no | moderate | WHO Classification 2018 | Assumed to be the same as Flurandrenolide and Fludroxycortide. |

| fluticasone propionate | 0.005% | ointment | yes | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| fluticasone propionate | 0.05% | cream | yes | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| GW870086X | 2% | cream | NA | NA | NA | Novel corticosteroid. |

| GW870086X | 0.2% | cream | NA | NA | NA | Novel corticosteroid. |

| halcinonide | 0.1% | cream | no | potent | WHO Classification 2018 | |

| halobetasol propionate | 0.05% | cream | no | very potent | Resource Clinical (USA) | Not listed in any of the other charts. |

| halometasone | 0.05% | cream | no | potent | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | In European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines as potent but no % given or preparation and not in any other charts listed. |

| hydrocortisone | 1% | cream | no | mild | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| hydrocortisone | 1% | fatty cream | no | mild | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Assume as for a standard preparation, therefore mild. |

| hydrocortisone | 1% | ‐ | no | mild | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| hydrocortisone | ‐ | cream | no | mild | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Assume a standard strength, therefore mild. |

| hydrocortisone | 1% | ointment | no | mild | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| hydrocortisone | 2.5% | ointment | no | mild | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| hydrocortisone | 0.5% | cream | no | mild | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| hydrocortisone | 0.5% | hydrophilic ointment | no | mild | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | Assume as for a standard 0.5% ointment, therefore mild. |

| hydrocortisone 17‐butyrate | 0.1% | cream | no | potent | British National Formulary 2015 | |

| hydrocortisone 17‐butyrate | 0.1% | fatty cream | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assuming potent as for ointment and cream. |

| hydrocortisone 17‐butyrate | 0.1% | lotion | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assuming potent as for ointment and cream. |

| hydrocortisone 17‐butyrate | 0.1% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2015 | |

| hydrocortisone acetate | 1% | ointment | no | mild | WHO Classification 2018 | Assume mild in WHO Classification 2018 as for the cream. |

| hydrocortisone buteprate | 0.1% | fatty cream | no | moderate | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | Hydrocortisone 17‐butyrate, 21‐propionate |

| hydrocortisone butyrate | ‐ | ‐ | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | No strength or preparation given, so assuming potent as for standard 0.1% cream or ointment. |

| hydrocortisone valerate | 0.2% | cream | no | moderate | WHO Classification 2018 | |

| hydrocortisone valerate | 0.2% | ointment | no | moderate | WHO Classification 2018 | |

| methylprednisolone aceponate | 0.1% | cream | no | potent | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | |

| methylprednisolone aceponate | 0.1% | ointment | no | potent | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | |

| methylprednisolone aceponate | 0.1% | fatty ointment | no | potent | Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme 2022 | |

| methylprednisolone aceponate | 0.1% | lotion | no | potent | Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme 2022 | Only chart where it is listed as a lotion. |

| methylprednisolone aceponate | ‐ | cream | no | potent | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines | Assume 0.1% and therefore potent. |

| mometasone furoate | 0.1% | ointment | yes | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| mometasone furoate | 0.1% | cream | yes | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| mometasone furoate | 0.1% | fatty cream | yes | potent | British National Formulary 2018 | |

| mometasone furoate | ‐ | cream | yes | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2018 | assume 0.1%, therefore potent. |

| prednicarbate | 0.25% | cream | no | moderate | Kim 2015 | |

| prednicarbate | 0.25% | ointment | no | moderate | Kim 2015 | |

| prednicarbate | ‐ | ointment | no | moderate | National Psoriasis Foundation (USA) | no % given ‐ in National Psoriasis Foundation (USA) chart as prednicarbate 0.1% cream (Dermatop) as moderate potency. |

| prednisolone 17‐valerate 21‐acetate | 0.30% | ‐ | no | moderate | Kim 2015 | |

| tralonide | 0.025% | ointment | no | potent | Scherrer 1974 | Discussed with other old potent preparation and it is fluorinated, therefore we assume potent. |

| triamcinolone | 0.1% | cream | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assume triamcinolone acetonide and as for the ointment. |

| triamcinolone | 0.1% | ointment | no | potent | inferred from British National Formulary 2015 | Assume this is triamcinolone acetonide, therefore ointment is potent. |

| triamcinolone acetonide | 0.1% | ointment | no | potent | British National Formulary 2015 |

NA: not applicable

Types of outcome measures

We will evaluate outcomes identified by the Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative as core outcome domains for eczema treatment trials (Williams 2022).

We will divide outcomes into short‐term (1 to 16 weeks after initiation of treatment) and long‐term (> 16 weeks after initiation of treatment). For outcomes measured at multiple time points, we will evaluate the time point closest to 12 weeks for short‐term and closest to one year for longer‐term outcomes. If there are equidistant assessments of the same outcome in the same trial, for example at eight weeks and 16 weeks, we will use the time point with the lowest risk of bias information; if this is equal, we will use the time point with the most complete data; and if this is equal, we will use the longer outcome, since patient and public involvement has indicated an interest in longer‐term outcomes where they are available.

Primary outcomes

There will be two co‐primary outcomes:

-

Patient‐reported symptoms of eczema. We will extract data based on the following instruments, in decreasing priority order:

Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) ‐ based on consensus in the HOME initiative (Spuls 2017);

Itch measured using an instrument recommended by HOME – currently the Peak Pruritus‐Numerical Rating Scales (PP‐NRS; Yosipovitch 2019);

Patient‐Oriented SCORAD (PO‐SCORAD; Stalder 2011);

Itch measured using other instruments such as the Leuven Itch Scale (LIS; Haest 2011), Itch Severity Scale (ISS; Majeski 2007), or Visual Analogous Scales (VAS);

Self Administered Eczema Area and Severity Index (SA‐EASI; Housman 2002);

Patients’ Global Assessment (PGA; Farina 2011);

Atopic Dermatitis Assessment Measure (ADAM; Charman 1999);

Any other instruments.

-

Clinician‐reported signs of eczema. We will extract data based on the following instruments, in decreasing priority order:

Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI; Hanifin 2001) ‐ based on consensus in the HOME initiative (Schmitt 2014);

Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD; Kunz 1997);

Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis (SASSAD) severity score (Charman 2002);

Body Surface Area (BSA) affected;

Any other instruments.

We will consider the Investigators’ Global Assessment (IGA) separately from other clinician‐reported signs of eczema, since the construct of IGA as a single global assessment differs from other measures of eczema signs. We are also conscious of the emphasis that some regulatory authorities place on IGA as an outcome separate to other measures of eczema signs. Therefore, we will always extract data for IGA, where reported, in addition to other measures of clinician‐reported signs of eczema. For the NMA, we will dichotomise the IGA score (i.e. convert the reported score for each participant into a binary score where 1 = clear or almost clear eczema, or 0 = moderate or no improvement), measured either alone or as part of a composite measure. That means, for an individual trial, IGA will be reported as the number of participants achieving the threshold closest to clear or almost clear eczema. If there is significant heterogeneity in the NMA of IGA, we will explore the impact of these choices, e.g. composite versus non‐composite measures of IGA, as one possible source of heterogeneity in a sensitivity analysis. We will record how each study characterised IGA eczema severity and will use the following hierarchy of preferred measures:

IGA score indicating clear or almost clear eczema (e.g. a score of 0 or 1) or a comparable construct;

IGA score which uses a composite of clear or almost clear eczema together with a single measure of another aspect of IGA, for example a specific level of BSA affected or a specific level of improvement/change (such as 2‐point reduction in IGA score);

IGA severity of eczema measured in another binary way, which is not comparable to ‘clear or almost clear’ versus other;

IGA response of eczema reported as a binary measure;

IGA severity of eczema reported as a continuous measure;

IGA response of eczema reported as a continuous measure.

Secondary outcomes

There will be three secondary outcomes.

-

Health‐related quality of life. We will extract data based on the following instruments, in decreasing priority order:

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; Finlay 1994)), including Children’s DLQI; CLDQI) and Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQOL).

Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD; Whalley 2004)

Skindex (Chren 2012)

Any other disease‐specific health‐related quality of life instrument

-

Long‐term control of eczema. We will extract data based on the following instruments, in decreasing priority order:

Recap of Eczema Control (RECAP; Howells 2020)

Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT; Pariser 2020)

Any other instruments

-

Adverse effects, namely:

Withdrawal from treatment or from study clearly due to adverse effects of the intervention.

Occurrence of cosmetic effects, including skin thinning/atrophy, which was identified to be of particular concern to people with eczema in relation to TCS through patient and public involvement in protocol development.

Number of tolerability events (e.g. application site reactions/stinging).

Search methods for identification of studies

We aim to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist (Liz Doney) will search the following databases and trials registers for relevant trials with no restriction by date:

The Cochrane Skin Specialised Register 2021 via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946 onwards); and

Embase via Ovid (from 1974 onwards).

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist has devised draft search strategies for RCTs for MEDLINE and Embase (Ovid), and CENTRAL in the Cochrane Library, which are displayed in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3, respectively. Another Cochrane Information Specialist will peer‐review the draft MEDLINE strategy prior to its execution, using the Search methods and strategy peer review assessment form for Cochrane intervention protocols. The MEDLINE strategy will be used as the basis for search strategies for the other databases listed above.

Trial registers

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), using the search strategy in Appendix 4.

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry (WHO ICTRP) search platform (www.who.int/trialsearch), using the search strategy in Appendix 5.

Searching other resources

Searching reference lists

We will examine the bibliographies of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to potentially eligible studies.

Correspondence with trialists

We will generally not contact trial authors or sponsors for missing data, but we will do this in cases of suspected fraud and in cases where key data points, such as standard deviations, are missing from the published reports and cannot be reliably estimated.

Adverse effects

We will not perform a separate search for adverse effects of the target interventions. We will consider data on adverse effects from the included studies only.

Errata and retractions

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist will run a specific search to identify errata or retractions related to our included studies, and we will examine any relevant retraction statements and errata that are retrieved.

Data collection and analysis

Screening search results

We will use Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow, available on the Cochrane Information Specialist’s portal, to help assess the search results (Marshall 2018; Noel‐Storr 2020; Noel‐Storr 2021; Thomas 2021). Screen4Me comprises three components, of which we will use two:

known assessments – a service that matches records in the search results to records that have already been screened in Cochrane Crowd and have been labelled as 'an RCT' or as 'not an RCT';

the RCT classifier – a machine learning model that distinguishes RCTs from non‐RCTs.

For clarity, the unit of interest for this review is the study. Multiple reports of a single study (full papers, conference abstracts, posters, etc.) will be grouped under a single study reference identification.

Selection of studies

After using the Cochrane Screen4Me workflow, two review authors (SL, CR) will independently screen a 5% random sample of the rejected Screen4Me references to confirm they are not eligible. The authors will then independently examine the remaining titles and abstracts using Covidence to determine whether studies meet our inclusion criteria, and all full texts will then be examined to confirm suitability for inclusion. Disagreements will be resolved by discussion with an experienced systematic review author (RB or AD).

We will follow the PRISMA guideline (NMA extension) for reporting, and will summarise in a PRISMA flow diagram the number of eligible studies identified (Hutton 2015). This will include the number of studies identified but excluded as ineligible, the total number eligible for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis, and the number included in the analysis. We will record the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

We will use a standardised data extraction form to extract from published reports both the desired outcome data detailed under Types of outcome measures and the characteristics of included studies. We will pilot the data extraction form prior to initiation of formal data extraction. We will extract data on the following descriptors, baseline characteristics, and effect modifiers.

Author and year of publication

Methods: study design, sample size, duration of trial participation

Participants: geographical location, community or healthcare setting, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, number of individuals randomised, number of withdrawals, baseline characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, duration of eczema, eczema severity)

Interventions: name of interventions and comparators, frequency, duration, concurrent treatment, site treated (face included/excluded)

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, time points reported

Notes: original language of publication, sponsorship/funding for trial, trial registration, dates trial conducted, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors

One team member (SL or JH) will conduct the data extraction and another team member (BS) will check it. One member of the team (SL or JH) will extract study characteristics, and another (JH or SL) will check them, with disagreements about data extraction or study characteristics resolved by discussion or reference to another member of the study team as needed (RB or AD). One author (LS) will enter data into the Cochrane RevMan Web computer software (RevMan Web 2022) or Stata version 16 or above, and a second team member (BS) will check the data entry.

We will summarise the characteristics of each included study in a characteristics of included studies table, and will manage missing data as detailed in Dealing with missing data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We will use the RoB 2 tool to evaluate risk of bias in included study outcomes (Sterne 2019). This allows risk of bias to be evaluated ‘per outcome’ rather than just ‘per study’. We will focus on the outcomes to be included in the summary of findings tables, and will use the latest versions of the Microsoft Word templates for parallel‐group trials, the first phase of cross‐over trials, and cluster‐randomised trials, as appropriate (from www.riskofbias.info). We will use the signalling questions and algorithms in the RoB 2 tools and associated guidance to make judgements about risk of bias for each domain. The answers to the full signalling questions will be available in an online repository at the time of full review publication. RoB 2 assesses the following domains.

Bias arising from the randomisation process

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions – here we will be assessing the effect of assignment, and not the effect of adherence

Bias due to missing outcome data

Bias in measurement of the outcome

Bias in the selection of the reported result

Two review authors will perform this assessment independently (SL, JH, LS, CR), with recourse to an experienced systematic review author (RB or AD) if there is disagreement. To reach an overall risk of bias judgement for a specific outcome, we will use the following criteria.

Low risk of bias ‐ all domains considered low risk for the specific result,

Some concerns ‐ some concerns have been raised in at least one domain for the specific result, but no domains are considered at high risk of bias,

High risk of bias ‐ at least one domain is considered high risk for the specific result or there are some concerns for multiple domains which substantially lowers confidence in the result.

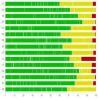

An example illustration of within study bias contributions is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Within study bias contributions. Within‐study overall risk of bias will be evaluated as ‘high’ where there is high risk of bias in at least one domain, or where there are some concerns in more than one domain; some concerns where there are some concerns in only one domain and no domains with high risk of bias; and low where all domains have a low risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For both pairwise and network meta‐analyses

Continuous outcomes

For continuous variables, if all studies use the same scale, we will report the mean difference (MD) with associated 95% confidence interval (CI) using this scale. However, if studies use different scales to measure the continuous outcome (e.g. some studies use EASI and others use SCORAD), which is anticipated, we will report standardised mean difference (SMD) and associated 95% CI. We will interpret these according to the guidance regarding Cohen’s effect sizes in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2022). It is not possible to include both change from baseline and follow‐up scores within the same meta‐analysis if the meta‐analysis is reporting SMDs. Therefore, we will focus on follow‐up outcome data rather than change from baseline. We will note any obvious baseline differences and will incorporate these in the RoB2 assessment.

Binary outcomes

For binary outcomes we will calculate odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI. If there are outcomes with zero events or 100% of events in all arms, we will show them on the relevant forest plot but exclude them from the statistical meta‐analysis, as these outcomes will not be able to provide any information on relative effects. Where studies contribute zero events or 100% of events in at least one but not all arms, we will use a continuity correction of 0.5 (Sweeting 2004).

Outcomes with continuous and binary data

It is not possible to include both continuous and binary data within the same meta‐analysis. For the outcome ‘eczema signs’, we will extract both continuous and binary data as we expect many studies to report either or both measures; we will analyse these in separate pairwise and network meta‐analyses. As most studies measuring IGA will report binary data representing treatment successes, we will extract these in preference to continuous data. For other outcomes, such as ‘eczema symptoms’ or ‘quality of life’, we will only extract binary outcome data for trials where no continuous outcome data are reported that are suitable for data extraction.

Additional considerations for network meta‐analyses

The NMA will enable relative treatment effects and relative treatment rankings to be derived from the extracted data. Examples of how the results will be organised are given in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5.

2. Dummy treatment rankings with probability scores for outcome 1.

| Treatment A | Treatment B | Treatment C | Treatment D | Treatment E | Treatment F | |

| Best | 60.8 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 36.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 2nd | 36 | 44.6 | 22.2 | 18 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 3rd | 3 | 23.5 | 39.1 | 9.9 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| 4th | 0.2 | 29 | 32.7 | 12.9 | 19.7 | 4.6 |

| 5th | 0 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 6.9 | 63.7 | 17.2 |

| Worst | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 11 | 46.1 |

Data are dummy data for a theoretical outcome with multiple interventions. A table showing all outcomes (treatments as rows; outcomes as columns) will also be created if possible.

3. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of estimates for outcome 1.

| A | 0.045 (0.005, 0.442) | 0.346 (0.062, 1.930) | 0.456 (0.080, 2.583) | 0.135 (0.022, 0.805) | 0.312 (0.057, 1.700) |

| 22.078 (2.262, 215.487) | B | 7.643 (0.879, 66.473) | 10.063 (1.167, 86.773) | 2.970 (0.344, 25.618) | 6.885 (0.900, 52.689) |

| 2.889 (0.518, 16.101) | 0.131 (0.015, 1.138) | C | 1.317 (0.287, 6.039) | 0.389 (0.065, 2.311) | 0.901 (0.142, 5.731) |

| 2.194 (0.387, 12.435) | 0.099 (0.012, 0.857) | 0.759 (0.166, 3.484) | D | 0.295 (0.050, 1.746) | 0.684 (0.110, 4.262) |

| 7.434 (1.242, 44.496) | 0.337 (0.039, 2.904) | 2.574 (0.433, 15.304) | 3.389 (0.573, 20.053) | E | 2.318 (0.421, 12.757) |

| 3.206 (0.588, 17.476) | 0.145 (0.019, 1.111) | 1.110 (0.174, 7.061) | 1.462 (0.235, 9.103) | 0.431 (0.078, 2.373) | F |

Data are dummy data for a theoretical outcome with multiple interventions. Statistically significant estimates will be highlighted in bold.

4. Example percentage contribution matrix.

| ‐ | Study number | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | |

| Mixed estimates | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A:C | 21 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 0 |

| A:D | 21 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 2 |

| A:E | 7 | 24 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 1 |

| A:F | 5 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 16 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| B:C | 4 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 27 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 11 |

| B:D | 4 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 27 |

| B:E | 1 | 7 | 27 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| B:F | 2 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 24 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 24 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| C:D | 17 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 3 |

| C:E | 6 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 23 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| C:F | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 26 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 1 |

| D:E | 6 | 24 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| D:F | 7 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 18 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| E:F | 1 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| Indirect estimates | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A:B | 8 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 11 |

Data are dummy data for a theoretical outcome with multiple interventions.

5. Sample inconsistency table.

| Comparison | No.Studies | NMA | Direct | Indirect | Difference (95%CI) | P value |

| A:B | 2 | 0.4 | 0.27 | 2.27 | ‐2 (‐3.61,‐0.39) | 0.01 |

| A:C | 2 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 1.21 | ‐0.76 (‐1.59,0.08) | 0.08 |

| A:D | 0 | 0.2 | NA | 0.2 | NA | NA |

| A:E | 0 | 0.76 | NA | 0.76 | NA | NA |

| A:F | 0 | 0.85 | NA | 0.85 | NA | NA |

| B:C | 0 | 0.55 | NA | 0.55 | NA (NA,NA) | NA |

| B:D | 2 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.59 | ‐0.41 (‐1.54,0.73) | 0.48 |

| And so on… | 0 | ‐0.2 | NA | ‐0.2 | NA | NA |

Data are dummy data for a theoretical outcome with multiple interventions.

NA = not applicable

Unit of analysis issues

In parallel RCTs the unit of analysis will be the participant. For trials with differences in the level at which randomisation occurred (e.g. cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials), we will use guidance from the CochraneHandbook to consider the potential impact of this when conducting our analysis (Higgins 2021a).

Cluster‐randomised trials

In cluster‐randomised trials, the unit of analysis will be the groups of participants randomised to different interventions. If data from a cluster‐randomised trial were inappropriately analysed in the original publication, we will consider inclusion of the study by adjusting for the study design using intracluster correlation coefficients – either those reported in the study or calculated using data from the study, if appropriate. If appropriate data adjusted for the intracluster correlation coefficient are not available or cannot be derived, we will note this but will not use the data for analysis.

Cross‐over trials

We will include cross‐over trials, but we will only include data from the first phase of the trial due to the risk of carry‐over effects to subsequent periods.

Within‐participant trials

We will include within‐participant trials, but due to concerns about these trials will perform a sensitivity analysis excluding these trial designs (see Sensitivity analysis). When included, we will extract paired data from within‐participant trials where the unit of analysis will be the separate body part. For paired data from studies with no suspicion of contamination across intervention sites, we will perform analysis using the generic inverse‐variance method after accounting for within‐participant variability (Higgins 2021b). If paired data are not available, we will attempt to estimate the paired data using methods and guidance from the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2021a), and correct the variance using the Becker‐Balagtas method (Elbourne 2002). We will assume an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.5 in all calculations. For outcomes which affect the whole body (e.g. systemic adverse events), we will not extract data from within‐participant trials as it will not be possible to determine which treatment caused the event.

Multiple intervention groups

In we include trials assessing multiple interventions in different arms, we will first judge if multiple interventions are eligible for inclusion in pairwise meta‐analysis. If so, we will split the comparison groups into two or more groups to avoid double counting of participants. We will then use these data for both paired and network meta‐analyses, as appropriate. The nature of multi‐arm trials is taken into account as standard by the Stata network and mvmeta commands for network meta‐analyses.

Further details can be found in Appendix 6.

Dealing with missing data

For continuous outcomes, means and standard deviations are required for meta‐analysis. If the standard deviation is missing, we will attempt to calculate the value from the standard error of the mean difference as reported from 95% CIs or P values (Higgins 2021b). Where data are reported as interquartile ranges or ranges, we will follow the Cochrane Handbook guidance on estimating standard errors if the underlying data appear likely to be normally distributed. We will generally not contact trial authors or sponsors for missing data, but we will do this in cases of suspected fraud and in cases where key data points such as standard deviations are missing from the published reports and cannot be reliably estimated. We will limit these communications to any corresponding authors with a currently valid email address in the published paper or trial registry. If we contact authors, we will create a table detailing this contact and the outcome.

If numerical data are unavailable and data reported in figures or graphs need to be extracted, we will use the WebPlotDigitizer tool to extract the data (Rohatgi 2021).

For both continuous and binary data, in primary analyses and in any sensitivity analyses, we will follow the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle in the analyses by including data from all participants included in the trials irrespective of their compliance with the assigned intervention. Hence, we plan to include all randomised participants in the analysis, which requires measuring all participants’ outcomes. When outcomes for some participants are missing, we will use available case analysis data based on all participants with outcome data available. The proportion of missing data and reasons for missingness will contribute to the RoB 2 evaluation.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will explore conceptual (clinical and methodological) and statistical heterogeneity between included studies. We will explore clinical heterogeneity by assessing differences between studies in the characteristics of included participants, interventions, and outcomes. Methodological variability will include assessments of differences in study design and risk of bias between trials. We will quantify statistical heterogeneity within pairwise analyses using the I2 statistic, considering the thresholds defined in the CochraneHandbook for interpretation (Deeks 2021):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Where there is substantial or considerable heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50%), we will explore possible sources for heterogeneity including, where appropriate, sensitivity analyses excluding any studies identified as outliers. We will also explore heterogeneity by other sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses for potential effect modifiers (see Sensitivity analysis and Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). After investigating sources of heterogeneity, we will carefully consider whether presenting pooled estimates is appropriate.

An example relative treatment effects forest plot is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Example relative treatment effects forest plot with prediction intervals. Illustration of format for presenting relative treatment effects with prediction intervals and assessment of imprecision and heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess reporting bias, we will produce funnel plots. These investigate the relation between study effect size and its precision. The premise is that small studies are more likely to remain unpublished if their results are nonsignificant or unfavourable, whereas larger studies get published regardless, leading to funnel‐plot asymmetry (Ioannidis 2007). If validity conditions are met (i.e. low heterogeneity, 10 or more studies, at least one study with significant results, and a ratio of the maximal to minimal variance across studies greater than four (Ioannidis 2007)), we will produce funnel plots and use visual inspection and Egger's funnel plot asymmetry tests to assess for possible reporting bias at the outcome level. For network meta‐analyses, we will produce comparison‐adjusted funnel plots using the netfunnel command in Stata.

Our search strategy also encompasses clinical trial registries, so we will identify trials that should have published results but have not done so, which will aid in our understanding of reporting bias at the whole trial level.

Data synthesis

Pairwise analysis

We will undertake a pairwise meta‐analysis of all study data suitable for meta‐analysis, and describe narratively any extracted data which are not suitable for meta‐analysis. For our primary analysis, we will use the data evaluated as being at low risk of bias or with ‘some concerns’ about risk of bias, but we will not include data evaluated as being as at high risk of bias. We will not make adjustments for multiple testing, and will interpret results in totality with the emphasis on estimated intervention effects rather than significance tests. We will also perform subgroup analysis, as detailed under Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity.

We will perform pairwise meta‐analysis for each comparison with a random‐effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird method (DerSimonian 1986). This adjusts for heterogeneity between studies, which is likely. For dichotomous data, where results are estimated for individual studies with low numbers of events (< 10 in total) or where the total sample size is < 30 participants and a risk ratio is used, we will report the proportion of events in each group together with a P value from a Fisher’s Exact test.

As the primary focus of this systematic review is the NMA, we will only use the extracted data to create pairwise comparison summary of findings tables if NMA is not possible. The strategy for creating these summary of findings tables, and how confidence in results will be assessed, is detailed in the statistical analysis plan (Appendix 6).

Network meta‐analysis

For all outcomes, where feasible, we will undertake a full NMA to explore all direct and indirect comparisons. The primary NMA will only include those outcome data rated overall as low risk of bias or some concerns (i.e. we will exclude data at high risk of bias).

We will produce networks for the following outcomes.

Clinician‐assessed signs of eczema (continuous)

Clinician‐assessed signs of eczema (binary – using instruments other than IGA)

Clinician‐assessed signs of eczema (binary ‐ using IGA categorised as clear/almost clear versus not)

Patient‐reported symptoms of eczema (continuous)

Health‐related quality of life (continuous)

Safety ‐ withdrawals due to adverse events (binary)

We do not expect suitable data to be available for generating networks for the remaining outcomes: long‐term control of eczema (continuous), which is part of the HOME core outcome initiative; and local adverse effects attributed to topical anti‐inflammatory treatment, namely skin thinning/atrophy (binary) and number of tolerability events (binary). However, where data are available, we will produce networks for long‐term outcomes.

We also anticipate data will only be available for short‐term outcomes (1 to 16 weeks after initiation of treatment) and not long‐term outcomes (> 16 weeks after initiation of treatment). However, where data are available, we will produce networks for long‐term outcomes.

The anticipated nodes are: placebo/vehicle, no treatment, mild TCS, moderate TCS, potent TCS, very potent TCS, pimecrolimus 1%, tacrolimus 0.03%, tacrolimus 0.1%, tacrolimus 0.3%, crisaborole 2%, ruxolitinib 1.5%, delgocitinib 0.5%, tapinarof 1%. We will only include licensed doses and frequencies of administration.

Interventions which include a combination of topical anti‐inflammatory and additional product(s) that are unlikely to have a direct anti‐inflammatory effect, such as topical antibiotics, will be included in the relevant node with the topical anti‐inflammatory alone. Furthermore, we will not separate nodes according to presence or absence of co‐interventions applied to both treatment arms.

The NMA will be performed using a random‐effects model in Stata with the mvmeta command within the network suite of commands for NMA (White 2015) and the Stata commands for graphing, ranking and reporting network results (Chaimani 2013). We will use a frequentist framework. For the whole network, we will quantify heterogeneity using the heterogeneity parameter Tau, which is the estimated standard deviation of underlying effects across studies. We will use contour‐enhanced, comparison‐adjusted funnel plots to evaluate reporting bias for the NMA (Chaimani 2013). To rank the efficacy for all treatments, we will use Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) values, together with corresponding CIs, to indicate the uncertainty of rankings (Salanti 2011). We will estimate the rank probabilities of all the groups by estimating the SUCRA values of each group, ranging from zero to one, where larger SUCRA values indicates a better outcome.

Assessment of transitivity and consistency in the network meta‐analysis

We will describe and present the treatment network graphically as in Figure 3. This will determine whether NMA is feasible, as severe imbalance in the amount of evidence for each intervention may affect the power and reliability of the overall analysis. The geometry of the network will describe the number of included interventions (nodes) and the extent to which there are trials comparing different pairs of interventions (edges) (Ioannidis 2009; Mills 2013). Considerations of heterogeneity and coherence will also be important in determining whether synthesising the results across trials in an NMA is justifiable.

3.

Graphical representation of interventions and comparators. Example network plot created using dummy data. Nodes are based on number of participants and the thickness of the lines is based on the number of studies in each comparison.

The transitivity assumption is that there are no important differences between trials making different comparisons other than the treatments being compared. As such, estimates of an intervention's effect from indirect comparisons should be similar to those generated from direct comparisons. To assess similarities between trials, we will assess heterogeneity as well as the distribution of effect modifiers (baseline eczema severity, treatment duration). To assess consistency/coherence between evidence sources (i.e. that the treatment effects from direct and indirect evidence are equivalent), we will use both global and local approaches.

To evaluate local consistency, we will use the standard node‐splitting approach (also known as SIDE: Separating Indirect from Direct Evidence) and implement this via Stata’s sidesplit command, which is part of the network command suite. This allows the estimates given for each pairwise comparison to be split into direct and indirect components, and the difference between these components can be assessed for incoherence (White 2015).

To evaluate global design inconsistency within the whole network, we will use the 'design by treatment interaction' model (Veroniki 2013), which will estimate a global Chi2 statistic for network coherence. Statistical significance will be set at 5%. When interpreting incoherence tests we will consider the inconsistency factors as well as their uncertainty and the impact on clinical implications, based on visual inspection of the 95% CIs of direct and indirect odds ratios and the range of equivalence. Inconsistency factors will include eczema severity, age, risk of bias, method of outcome assessment (HOME approved versus not HOME approved), treatment duration, and trial design (within‐ versus between‐participant comparison).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We will undertake planned subgroup analyses for each pairwise and network meta‐analysis (all outcomes) according to the following characteristics, if reported in sufficient trials:

Site of treatment (studies that include facial application versus studies that do not)

Disease severity (moderate/severe versus mild disease)

Age < 12‐year‐olds versus ≥ 12‐year‐olds (most eczema resolves by age 12 years, so the distinction is between typical eczema of childhood and persistent or new‐onset eczema of adolescence/adulthood).

How best to treat sensitive sites, such as facial and genital skin, is of interest to people with eczema and healthcare professionals because of concerns over side effects with stronger topical treatments. Milder or more severe eczema, or eczema in different age groups, may also respond differently to different treatments, and the trade‐off of treatment benefits versus harms may be different for these groups.

We will use a statistical test of interaction to evaluate the possibility of subgroup effects and consider a P value of < 0.05 to indicate a significant interaction. All treatment estimates will be accompanied by two‐sided 95% CIs.

Sensitivity analysis

We will perform the following sensitivity analyses for outcomes included in summary of findings tables for both pairwise meta‐analyses and NMA.

All data (including data with high risk of bias)

Using an alternative TCS potency classification system, the United States 7‐point Classification system (1 = Super Potent, 2 = Potent, 3 = Upper Mid‐Strength, 4 = Mid‐Strength, 5 = Lower Mid‐Strength, 6 = Mild, 7 = Least Potent), expressed as a consolidated 4‐category scale.

-

Outcomes reported using the HOME core outcome measurement instruments only. These are currently:

EASI for clinical signs;

POEM or (for individuals old enough to self‐report symptoms) PP‐NRS for symptoms;

DLQI, CDLQI, or IDQoL for quality of life;

RECAP or ADCT for long‐term control.

We will perform these additional sensitivity analyses for NMA.

Analysis excluding within‐participant data for the eczema signs and symptoms networks only due to concerns about the validity of these study designs

-

Lumping of treatment nodes:

TCS are combined into mild/moderate and potent/very potent (i.e. 2 nodes);

TCI are combined into pimecrolimus 1%/tacrolimus 0.03% and tacrolimus 1%/3% (i.e. 2 nodes);

Other classes of topical anti‐inflammatories are included as a single node for each class of medication, (i.e. 1 node for PDE‐4 inhibitors, 1 node for JAK inhibitors, 1 node for AHR activators), unless there is a recognised split of products according to potency.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

To assess confidence in the evidence of the network of intervention, we will use the Confidence in NMA (CINeMA) approach (Nikolakopoulou 2020). Full details of this process are listed in Appendix 6. Two review authors will undertake this (SL, LS, JH, RB, AD, BS), with team meetings to resolve any discrepancies, where necessary. We will use CINeMA software for CINeMA assessments of the six domains detailed below.

Within‐study bias

Reporting bias

Indirectness

Imprecision

Heterogeneity

Incoherence

We will base our overall assessments of confidence on the grading in all six domains of CINeMA described above. We will start at high confidence and drop the level of confidence by one step for each domain with some concerns, and by two levels for each domain with major concerns. However, we will take account of the possibility that single issues might impact on multiple domains and avoid inappropriate multiple downgrades for single NMA issues.

We will produce summary of findings tables for NMA findings using the approach recommended by Cochrane and GRADE (Yepes‐Nunez 2019), but will be cautious in our interpretation of rankings due to concerns about the reliability of ranking information in summaries of NMA findings. We will create a separate NMA summary of findings table for each of the network outcomes for which a network was possible. An example is shown in Figure 4. CINeMA judgements and summary of findings tables will take into account the results both of the main analysis and of the planned sensitivity analyses and any subgroup effects or narrative information identified (Figure 5).

4.

Example NMA SoF table (Yepes‐Nunez 2019).

5.

CINeMA assessments. Data are dummy data for a theoretical outcome with multiple interventions.

The primary focus of this systematic review is the NMA, since Cochrane Reviews and other systematic reviews are already available for direct comparisons of topical anti‐inflammatory treatments versus placebo or no treatment. However, if NMA is not possible, then we will change strategy and use the extracted data to create pairwise comparison summary of findings tables as detailed in Appendix 6.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments from the authors

The authors would like to thank Liz Doney, Cochrane Skin Information Specialist, for developing the search methods and the draft search strategies; and Joanne Chalmers from the Centre of Evidence‐Based Dermatology for her contribution to development of this project and the grant application.

Editorial and peer‐reviewer contributions

Cochrane Skin supported the authors in the development of this protocol.

The following people conducted the editorial process for this article:

Sign‐off Editor (final editorial decision): Toby Lasserson, Cochrane Deputy‐in‐Chief, Evidence Production & Methods Directorate

Managing Editor (selected peer reviewers, collated peer‐reviewer comments, provided editorial guidance to authors, edited the article): Lara Kahale, Cochrane Central Editorial Service

Editorial Assistant (conducted editorial policy checks and supported editorial team): Lisa Wydrzynski, Cochrane Central Editorial Service

Copy Editor (copy‐editing and production): Andrea Takeda, Copy Edit Support

Peer‐reviewers (provided comments and recommended an editorial decision): Robin Featherstone, Cochrane Central Editorial Service (search review); Nuala Livingstone, Associate editor, Cochrane Evidence Production & Methods Directorate (methods review); Juan Jose Yepes‐Nuñez; Universidad de los Andes (clinical/content review); Audrey A Jacobsen, Departments of Internal Medicine and Dermatology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis MN USA (clinical/content review); and Nicole Zeeuw van der Laan (consumer review).

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (Ovid) draft search strategy

Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to March 07, 2022> with PR edits 1 exp Eczema/ or eczema$.ti,ab. 24634 2 Dermatitis, Atopic/ 22443 3 atopic dermatiti$.ti,ab. 23617 4 neurodermatiti$.ti,ab. or Neurodermatitis/ 1767 5 or/1‐4 49529 6 exp Emollients/ 5304 7 emollient$.ti,ab. 1949 8 moisturi$.ti,ab. 2958 9 exp Oils/ or oil.ti,ab. or oils.ti,ab. 206666 10 Ointments/ or ointment$.ti,ab. 19940 11 (cream$ or salve$ or unguent$ or lotion$).ti,ab. 25494 12 (topical$ adj3 (corticosteroid$ or corti‐costeroid$)).ti,ab. 7427 13 (topical$ adj3 steroid$).ti,ab. 6293 14 (topical$ adj3 (glucocorticoid$ or gluco‐corticoid$)).ti,ab. 603 15 (topical$ adj3 corticoid$).ti,ab. 145 16 alclometasone dipropionate.ti,ab. 23 17 amcinonide.ti,ab. 45 18 beclometasone dipropionate.ti,ab. 136 19 Betamethasone/ or betamethasone benzoate.ti,ab. 6178 20 Betamethasone butyrate propionate.ti,ab. 15 21 betamethasone dipropionate.ti,ab. 570 22 (betamethasone adj2 valerate).ti,ab. 693 23 clobetasol.ti,ab. or Clobetasol/ 1946 24 clobetasone.ti,ab. 114 25 clocortolone pivalate.ti,ab. 13 26 Deprodone propionate.ti,ab. 0 27 Desonide/ or desonide.ti,ab. 147 28 desoximetasone.ti,ab. or Desoximetasone/ 117 29 diflorasone.ti,ab. 37 30 Diflucortolone/ or diflucortolone.ti,ab. 138 31 fluclorolone.ti,ab. 9 32 (fludroxycortide or flurandrenolide or flurandrenolone).ti,ab. 69 33 Flurandrenolone/ 133 34 (flumetasone or flumethasone).ti,ab. 181 35 Flumethasone/ 311 36 fluocinolone acetonide.ti,ab. or Fluocinolone Acetonide/ 1690 37 fluocinonide.ti,ab. or Fluocinonide/ 288 38 fluocortin.ti,ab. 44 39 Fluocortolone/ or fluocortolone.ti,ab. 313 40 fluprednidene.ti,ab. 4 41 halcinonide.ti,ab. or Halcinonide/ 90 42 (halobetasol or ulobetasol).ti,ab. 93 43 halometasone.ti,ab. 35 44 hydrocortisone butyrate.ti,ab. 94 45 hydrocortisone aceponate.ti,ab. 25 46 hydrocortisone acetate.ti,ab. 753 47 hydrocortisone valerate.ti,ab. 10 48 ma?ipredone hydrochloride.ti,ab. 1 49 prednicarbate.ti,ab. 103 50 Prednisolone valerate acetate.ti,ab. 1 51 triamcinolone.ti,ab. or Triamcinolone/ 10317 52 Calcineurin Inhibitors/ 4213 53 calcineurin inhibitor$.ti,ab. 7822 54 Tacrolimus/ 17039 55 tacrolimus.ti,ab. 17558 56 fk506.ti,ab. 6261 57 pimecrolimus.ti,ab. 836 58 or/6‐57 310545 59 Janus Kinase Inhibitors/ 938 60 (JAK inhibitor$ or jakinib$ or janus kinase inhibitor$).ti,ab. 2968 61 59 or 60 3292 62 delgocitinib.ti,ab. 31 63 ruxolitinib.ti,ab. 1833 64 tofacitinib.ti,ab. 1868 65 JTE‐052.ti,ab. 9 66 Receptors, Aryl Hydrocarbon/ or aryl hydrocarbon receptor$.ti,ab. or AHR activator$.ti,ab. 8784 67 (tapinarof or WBI‐1001).ti,ab. 39 68 Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors/ 1330 69 ((PDE‐4 or phosphodiesterase) adj3 inhibitor$).ti,ab. 13509 70 68 or 69 14162 71 difamilast.ti,ab. 3 72 crisaborole.ti,ab. 128 73 Beclomethasone/ or beclomethasone.ti,ab. 3908 74 Budesonide/ or budesonide.ti,ab. 6721 75 exp Cortisone/ or cortisone.ti,ab. 23566 76 Hydrocortisone/ or hydrocortisone.ti,ab. or hydro cortisone.ti,ab. or cortisol.ti,ab. 103466 77 Dexamethasone/ or dexamethasone.ti,ab. 76419 78 fluticasone.ti,ab. 4135 79 Methylprednisolone/ 19781 80 (methylprednisolone adj (aceponate or acetate)).ti,ab. 828 81 (methyl adj prednisolone adj (aceponate or acetate)).ti,ab. 63 82 mometasone.ti,ab. 1056 83 Prednisolone/ or prednisolone.ti,ab. 48245 84 exp Adrenal Cortex Hormones/ 413211 85 Glucocorticoids/ 68465 86 Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/ 88468 87 (anti inflammator$ or antiinflammator$).ti,ab. 204631 88 or/73‐87 685830 89 administration, topical/ or administration, cutaneous/ 63523 90 Emollients/ 2039 91 Oils/ 12546 92 Ointments/ 13119 93 (topical$ or cutaneous or emollient$ or oil or oils or ointment$ or cream$ or salve$ or unguent$ or lotion$).ti,ab. 464369 94 or/89‐93 498032 95 88 and 94 38868 96 61 and 94 275 97 66 and 94 307 98 70 and 94 439 99 58 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 67 or 71 or 72 or 95 or 96 or 97 or 98 331411 100 randomized controlled trial.pt. 560324 101 controlled clinical trial.pt. 94719 102 randomized.ab. 552851 103 placebo.ab. 226123 104 clinical trials as topic.sh. 199418 105 randomly.ab. 377352 106 trial.ti. 257833 107 100 or 101 or 102 or 103 or 104 or 105 or 106 1430930 108 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 4968174 109 107 not 108 1316202 110 5 and 99 and 109 1584

Search narrative:

We contacted the North West Medicines Information Centre & National Dental Medicines Information Service (via email 24 November 2021) for advice on new topical medications for eczema that we should search for. They replied (1 December 2021) having run a report in their horizon scanning database suggesting crisaborole, ruxolitinib and delgocitinib. These terms have been incorporated into our search strategy.

Lines 1‐5: disease terms.

Lines 6‐11: generic topical treatment terms.

Lines 12‐51: steroids usually used in topical form.

Lines 52‐57: topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Lines 59‐65: JAK inhibitors.

Lines 66‐67: aryl hydrocarbon receptor activators.

Lines 68‐69: Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors.