Abstract

The display of peptide sequences on the surface of bacteria is a technology that offers exciting applications in biotechnology and medical research. Type 1 fimbriae are surface organelles of Escherichia coli which mediate d-mannose-sensitive binding to different host surfaces by virtue of the FimH adhesin. FimH is a component of the fimbrial organelle that can accommodate and display a diverse range of peptide sequences on the E. coli cell surface. In this study we have constructed a random peptide library in FimH. The library, consisting of ∼40 million individual clones, was screened for peptide sequences that conferred on recombinant cells the ability to bind Zn2+. By serial selection, sequences that exhibited various degrees of binding affinity and specificity toward Zn2+ were enriched. None of the isolated sequences showed similarity to known Zn2+-binding proteins, indicating that completely novel Zn2+-binding peptide sequences had been isolated. By changing the protein scaffold system, we demonstrated that the Zn2+-binding seems to be uniquely mediated by the peptide insert and to be independent of the sequence of the carrier protein. These findings might be applied in the design of biomatrices for bioremediation purposes or in the development of sensors for detection of heavy metals.

The potential threat of heavy-metal and radionuclide pollution for ecosystems and public health has led to an increased focus on the development of systems for their sequestration and removal from soil, sediment, and wastewater. So far, decontamination techniques have been based mostly on traditional physiochemical methods, but in recent years interest has also centered on the application of biotechnology to efficient waste treatment. To this end, a number of biological remediation systems have been established in bacteria, algae, fungi and plants (5, 11, 17, 26).

Expression of heterologous peptides in naturally occurring surface proteins has become a powerful tool in generating microorganisms with binding affinity toward specific target molecules. This technique has been employed in the development of recombinant live vaccines, reagents for diagnostics, antibody production, screening of peptide libraries, and design of microbial biocatalysts and has recently constituted an attractive approach to development of bacterial bioadsorbents for heavy-metal removal purposes (2, 9, 10, 15).

Random peptide library expression is a highly versatile technology. Systems in which such libraries are expressed in connection with a surface protein scaffold allow the screening of a huge number of peptides (∼108) from which binders to a particular molecular target can be isolated by various panning techniques (6).

A well-characterized scaffold system for display of heterologous peptides is based on type 1 fimbriae. These are hair-like surface organelles present on most members of the Enterobacteriaceae. Type 1 fimbriae are found in up to 500 copies on the cell; they are heteropolymers, and each fimbria consists of about 1,000 copies of the major structural subunit, FimA. The d-mannose-specific FimH adhesin, located on the tip and perhaps also intercalated along the organelle, is also a structural component. By site-directed mutagenesis, we have previously identified permissive sites in FimH that allow the insertion and surface display of heterologous sequences without altering the overall structure and function of FimH (14, 21). Such sites have been used for display of vaccine-relevant epitopes (14). Recently, we have successfully used the FimH protein as a molecular scaffold for the display of random peptide libraries (7, 19, 20). In this paper we report the identification of novel Zn2+-binding peptides selected from a FimH-displayed random peptide library. Our results indicate that the zinc binding can be a unique property of the displayed peptide and independent of the protein scaffold.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

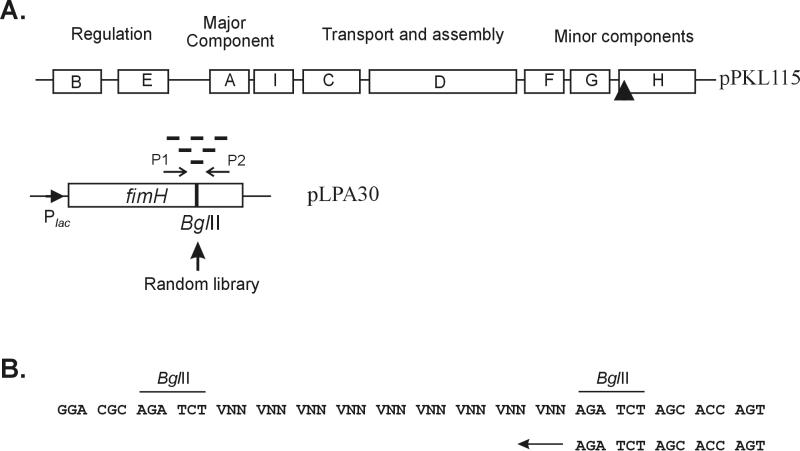

In this study we used the E. coli K-12 strain S1918 (F′ lacIq ΔmalB101 endA hsdR17 supE44 thiI relA1 gyr-96 ΔfimB-H::kan) (3). Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Our FimH display system consists of two plasmids, the FimH expression vector pLPA30 and an auxiliary plasmid pPKL115. Plasmid pLPA30 is a pUC18 derivative containing the fimH gene downstream of the lac promoter. A BglII linker, located in a position corresponding to amino acid 225 (14), was used for integration of the random library. Plasmid pPKL115 is a pACYC184 derivative containing the whole fim gene cluster with a translational stop linker inserted in the fimH gene (14).

DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Plasmid kit (Qiagen). Restriction endonucleases were used as specified by the manufacturer (Biolabs or Pharmacia). PCR amplifications to monitor the size and distribution of the random library were performed as previously described (24). The oligonucleotide primers used in these reactions were P1 (5′-CCTGCACAGGGCGTCGGCGTAC) and P2 (5′-GGAATAATCGTACCGTTGCG). The nucleotide sequences of inserts conferring on cells the ability to bind to metal oxides were determined by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (18).

Construction of the random peptide library.

Construction of the random library was performed essentially as described by Brown (3). Briefly, a template oligonucleotide containing the sequence 5′-GGACGCAGATCT(VNN)9AGATCTAGCACCAGT-3′ (where N indicates an equimolar mixture of all four nucleotides and V indicates an equimolar mixture of A, C and G) was chemically synthesized. A primer oligonucleotide, 5′-ACTGGTGCTAGATCT-3′, was hybridized to the template oligonucleotide and extended with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. The double-stranded oligonucleotide was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and digested with BglII to release an internal 33-bp fragment. This was purified by electrophoresis through a 12% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) and eluted into a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, and 0.15 M NaCl. The eluate was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size Qiagen filter, concentrated by ethanol precipitation, and redissolved in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M NaCl. The redissolved 33-bp BglII fragment was ligated at various ratios to BglII-digested pLPA30. The ligation products were precipitated with ethanol and electroporated into S1918(pPKL115).

The diversity of the library was calculated to be 4 × 107 individual clones based on extrapolation from the numbers of transformants obtained in small-scale platings. The transformation mixture was made up to 10 ml and grown for approximately seven generations (4 × 109 cells). Aliquots (1 ml) were frozen at −80°C in 25% (vol/vol) glycerol. Each 1-ml aliquot contained approximately 4 × 108 cells, which represented 10 times the library diversity. Random screening of clones by PCR revealed a predominance of one to three 33-bp oligonucleotide inserts; sequencing of the inserts from randomly selected clones revealed G+C contents ranging from 30 to 70%.

Enrichment procedure.

Bacterial cells were bound to zinc ions by use of stripped Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) solid matrix (Qiagen) recoated with Zn2+ by a standard method. The enrichment procedure for identifying Zn2+-binding clones from the random library was as follows. Mid-exponential-phase cultures were diluted into M63 salts (13) containing 20 mM methyl α-d-mannopyranoside and 50% (vol/vol) Percoll (Pharmacia). The methyl α-d-mannopyranoside was added to block the natural receptor-binding domain of the FimH adhesin. The use of Percoll permitted the formation of a density gradient on centrifugation, which resulted in a distinct band due to the Zn2+-NTA resin, and specific separation of any adherent bacteria from nonadherent bacteria. Under these conditions, bacteria expressing wild-type FimH proteins as components of type 1 fimbriae did not coseparate with the Zn2+-NTA resin. The resin and bacteria expressing the random peptide library within FimH were mixed and allowed to adhere at room temperature with gentle agitation. Centrifugation was then performed, and the resin and any adhering bacteria were recovered and inoculated into Luria-Bertani medium containing appropriate antibiotics. After overnight incubation, exponentially growing cultures were established and the enrichment procedure was repeated. Following each cycle of enrichment, aliquots of the populations were stored at −80°C. Plasmid DNA was prepared from each aliquot and used in PCR to monitor the size distribution of the inserts in the population as previously described (19).

Binding assay and quantification.

Mid-exponential-phase cultures standardized on the basis of their optical density at 550 nm (OD550) were washed and resuspended in M63 salts containing 20 mM methyl α-d-mannopyranoside. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 15 min with gentle agitation before the addition of Zn2+-NTA agarose beads. After a 15-min incubation with gentle agitation, the beads were examined by phase-contrast microscopy (Carl Zeiss Axioplan microscope) and digital images were captured with a 12-bit cooled slow-scan charge-coupled device camera (KAF 1400 chip; Photometrics, Tucson, Ariz.) controlled by PMIS software (Photometrics).

The ability of individual clones to bind to Zn2+ was measured by counting cells attached to a selection of randomly chosen Zn2+-NTA beads and correlating the number of adhering cells to the bead size. The same procedure was used for quantification of cells binding to Ni2+-NTA and Cu2+-NTA beads.

Agglutination of yeast cells.

The capacity of bacteria to express a d-mannose-binding phenotype was assayed by their ability to agglutinate yeast cells (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) on glass slides. Aliquots of washed bacterial suspensions at an OD550 of 1.0 and 10% yeast cells were mixed, and the time until agglutination occurred was measured.

Insertion of a CTB loop in fimH.

Two oligonucleotides, oligonucleotide KK12 (5′-GATCTGTTGAAGTTCCGGGATCCCAGCATATCGATAGTCAGAAA AAAGCTA-3′) and oligonucleotide KK13 (5′-GATCTAGCTTTTTTCTGACTATCGATATGCTGGGATCCCGGAACTTCAACA-3′) encoding amino acids 50 to 64 of cholera toxin B chain (CTB), were designed so that they contained an internal BamHI site at amino acid position 54 and were flanked by BglII overhangs. These oligonucleotides were annealed, phosphorylated, and ligated into pLPA30 digested with BglII. The resultant plasmid (pKKJ16) was checked by BamHI digestion and sequencing. Plasmid pKKJ16 (containing the loop of CTB in fimH) was transformed into S1918(pPKL115).

Engineering a Zn2+-binding peptide into the CTB3 loop in FimH.

The Zn2+-binding sequence of pKKJ106 was amplified by PCR using primers KK77 (5′-GCCCGGATCCGAAAGCAGGGTCGACC-3′) and KK78 (5′-GCCCGGATCCTTGGTGATGACGCTCTG-3′) containing BamHI overhangs. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and ligated into pKKJ16 digested with BamHI. The resultant plasmid (pKKJ145) was checked by sequencing and transformed into S1918(pPKL115).

Fimbria purification.

OD550-standardized overnight cultures were harvested by centrifugation and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were resuspended in PBS, and fimbriae were detached from the cell surface by blending. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the fimbriae in the supernatant were precipitated with acetone. The purified fimbriae were dried and resuspended in PBS (8).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western immunoblotting.

Purified fimbriae were treated with diluted HCl (pH = 2) and separated on 15% polyacrylamide gels by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis by using standard procedures (16). The gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride microporous membrane filters using a semidry blotting apparatus. The membranes were blocked with 0.5% Tween 20 and incubated with anti-FimH (truncated) serum followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit serum.

RESULTS

Library construction in FimH.

A random peptide library based on oligonucleotides 33 bp in length with BglII overhangs was constructed for display in the type 1 fimbria adhesin FimH (Fig. 1). To this end, we used a vector (pLPA30) containing the fimH gene with a BglII linker inserted at codon position 225 and under the transcriptional control of the lac promoter (14). Insertions in this position have previously been shown to permit the expression of heterologous sequences without affecting the properties of FimH. The inserted double-stranded oligonucleotides consisted of nine random codons flanked by BglII restriction sites (encoding Arg-Ser). Due to the presence of BglII overhangs, various numbers of double-stranded oligonucleotides were inserted in fimH, further adding to the complexity of the library. To express FimH variants as constituents of fimbriae, an auxiliary plasmid (pKKL115), containing all fim genes except fimH, was used for transcomplementation of the fimH-containing plasmid. Expression from the binary plasmid system led to display of chimeric FimH in the context of fully functional fimbriae.

FIG. 1.

Overview of random peptide display in type 1 fimbriae. (A) The binary plasmid systems used in heterologous display by FimH. Plasmid pPKL115 contains the entire fim gene cluster with a translational stop linker inserted in the fimH gene (indicated by the solid triangle). The FimH expression vector pLPA30 is shown, along with the BglII insertion site at amino acid 225 and the two primers (P1 and P2) used to monitor the size and distribution of the random library. (B) Genetic structure of the random library inserted into fimH. The two oligonucleotides were annealed and extended with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and the product was purified after digestion with BglII. N indicates an equimolar mixture of all nucleotides, and V indicates an equimolar mixture of A, C, and G. The use of a VNN coding system prevents the introduction of functional stop codons in an amber-suppressing host.

Selection and identification of Zn2+-binding sequences.

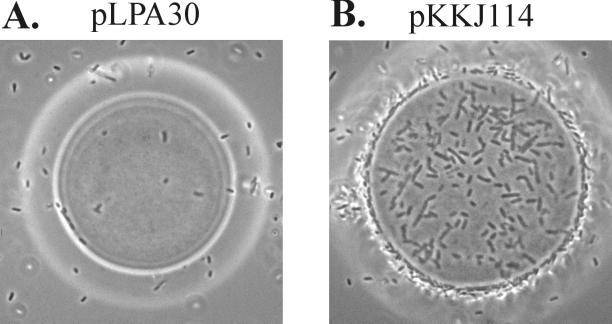

Cells able to adhere to Zn2+ were isolated from the FimH-displayed random library after repetitive rounds of selection. The cells were allowed to bind to Zn2+-NTA beads, and binding cells were separated from nonbinders by density gradient centrifugation in 50% (vol/vol) Percoll. Bacteria adhering to the Zn2+-NTA beads were recovered and transferred to fresh growth medium. The enrichment procedure was repeated, and the insert distribution of the population was monitored by PCR (data not shown). No change in the insert population was observed in a control experiment, in which neither Zn2+-NTA nor Percoll was present during the enrichment procedure. However, a notable change in the insert distribution was observed after three rounds of enrichment with Zn2+-NTA. Cells obtained from the third enrichment cycle were spread onto agar plates, and cultures were established from 20 single colonies. The ability of cells expressing the enriched peptides to adhere to Zn2+-NTA was examined by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 2). Of the 20 clones, 15 displayed a Zn2+-binding phenotype. To ensure that the observed binding phenotype was indeed FimH based, each of the fimH-encoding plasmids was isolated and retransformed into S1918(pPKL115). The new recombinant clones displayed the same binding phenotype as the original isolates, indicating that the binding phenotype was indeed plasmid encoded. Furthermore, the agglutination titers of these cells were similar to that of a control strain expressing wild-type FimH, indicating that the presence of the inserts had not significantly altered the amount of surface-displayed FimH.

FIG. 2.

Phase-contrast microscopy showing adherence to Zn2+-NTA beads by S1918(pPKL115) cells containing plasmid pLPA30 (wild-type fimH) (A) or plasmid pKKJ114 (random library clone isolated after selection for adherence to Zn2+-NTA beads) (B).

The nucleotide sequences of the inserts were determined. The 15 selected clones had one to three 33-bp inserts, and all of these were different (Table 1). However, one of the two inserts present in pKKJ116 was also found in pKKJ106, indicating that this sequence plays a role in Zn2+ binding. No obvious consensus sequence could be deduced from the sequences. However, taking the VNN design of the random library into account, sequences containing histidines were enriched (18.4% found versus 4.2% expected) and 14 of 15 clones carried histidine-containing inserts. This should be seen in light of the fact that histidine is known to participate in the coordination of divalent metal ions in many metal-binding proteins (25). However, the presence of histidine residues was not the only criterion for zinc binding since one of our clones, pKKJ113, had three inserts, none of which contained histidines. Comparison of the selected sequences with sequences in the Swiss-Prot database revealed no noteworthy sequence similarity. These findings suggest that completely novel Zn2+-binding peptides were enriched from our library.

TABLE 1.

Isolated sequences conferring the ability to adhere to Zn2+-NTAa

| Plasmid | Enriched amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| pKKJ108 | R S D R G K A H P S R R S |

| pKKJ117 | R S S G Y M T D T G P R S K H H P R N R E T R S |

| pKKJ109 | R S V H A S H H H I M R S |

| pKKJ110 | R S R L G H P V N H HR S R L A E Q I S Q R R S |

| pKKJ106 | R SH A R A E R H H Q R S |

| pKKJ116 | R S E S R V D P A A D R SH A R A E R H H Q R S |

| pKKJ113 | R S F S V T S Y S N G R S V G Q V E P A G R R S Q P P D V T R P R R S |

| pKKJ120 | R S V L R H L H L R R R S G D D L H E T A A R S |

| pKKJ105 | R S K L G H S P T I HR S E D Q S A Q A H A R S |

| pKKJ122 | R S L Q L R T G P G L R S H P I G R R T K HR S |

| pKKJ119 | R S G V H R N R I H K R S |

| pKKJ118 | R SH E L H T H A R S R S |

| pKKJ121 | R S Q L A R H H K H I R S |

| pKKJ115 | R S T G I H V I H H M R S |

| pKKJ114 | R S M N P R T H A T T R S N M H H A A G A S R S |

Sequences are listed with the weakest binding sequence at the top and strongest binding sequence at the bottom. Histidine residues are highlighted in bold face, and the amino acids encoding BglII restriction sites are underlined.

Quantification of binding with enriched sequences.

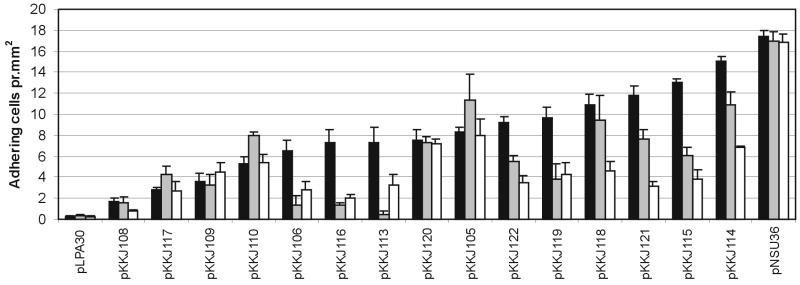

To determine the affinity toward Zn2+, the number of cells associated with Zn2+-NTA beads for each of the selected clones was determined. By correlating the bead surface area with the number of bound cells, a significant difference in affinity was observed for the examined clones (Fig. 3). Indeed, a ∼10-fold difference was seen between the clones with highest and lowest affinity, respectively. As a positive control, we used cells expressing a FimH variant (pNSU36) containing an insert with 12 histidine residues, which has previously been shown to mediate strong binding to divalent metal ions (20). Cells expressing wild-type FimH (pLPA30) were used as a negative control.

FIG. 3.

Quantification of Zn2+ binding (solid bars), Ni2+ binding (gray bars), and Cu2+ binding (open bars) by isolated clones from the random library. The clones are listed according to their affinity toward Zn2+. The average number of adhering cells per square millimeter of NTA bead is indicated for each clone. Plasmid pNSU36 expressing polyhistidine in FimH represents a positive control, and pLPA30 expressing wild-type FimH represents a negative control. The values are means and standard errors of means (n = 5) based on a 95% level of confidence.

The binding data showed no correlation between the number of histidine residues present in the enriched sequences and the affinity of the clones. In fact, clone pKKJ113 with an insert sequence devoid of histidine displayed greater affinity toward Zn2+ than did a clone with an insert containing no less than four histidine residues (pKKJ109). This demonstrates that the presence of histidine is not an absolute requirement for binding to Zn2+ in our FimH display system.

Binding specificity of enriched sequences.

To determine the binding specificity of the Zn2+-enriched clones, the ability of these to bind to Ni2+-NTA and Cu2+-NTA was investigated. Ni2+ and Cu2+ were used due to their chemical similarity to Zn2+, as expected from the close proximity of these metals in the periodic table of the elements. Prominent differences in binding specificity toward Zn2+, Ni2+, and Cu2+ were observed among the clones (Fig. 3). For example, clones harboring pKKJ113 and pKKJ116 exhibited ∼16- and ∼5-fold-better binding to Zn2+ than to Ni2+, respectively, whereas pKKJ105 actually had higher affinity toward Ni2+ even though it had been selected for Zn2+ binding. As expected, the positive control containing a 12-histidine insert was unable to distinguish among the three metal ions. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the enriched clones not only have different degrees of affinity toward Zn2+ but also exhibit highly variable affinity toward two related heavy-metal ions, Ni2+ and Cu2+.

Zn2+ binding is uniquely mediated by a peptide insert.

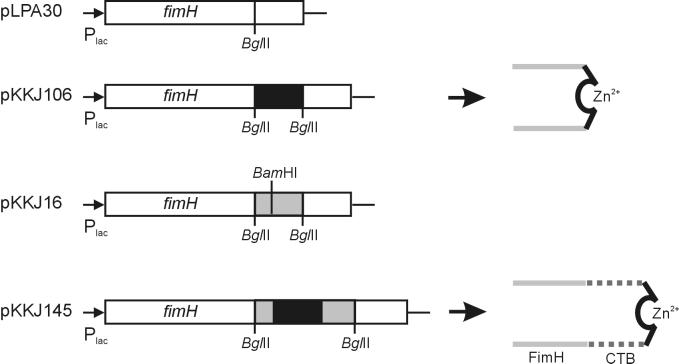

In theory, Zn2+ chelation can be mediated uniquely by residues in the peptide insert or by a combination of residues both in the insert and in the FimH protein scaffold. To investigate this issue further, an additional scaffold was introduced into FimH to increase the distance between the FimH peptide backbone and the insert. Arguably, this would also change the molecular surroundings of the insert dramatically. As a relevant secondary scaffold, we chose a well-characterized region of CTB, i.e., the CTB3 epitope, consisting of amino acids 50 to 64. The CTB3 epitope has previously been shown to comprise a conformational loop on the surface of CTB with a high degree of conformational plasticity (12, 22). Furthermore, this epitope has previously been shown to be authentically displayed at position 225 in FimH (14). A synthetic DNA segment encoding the CTB3 loop was made by annealing two complementary 51-bp oligonucleotides, which were designed to contain BglII overhangs in order to allow insertion into the fimH gene. To be able to introduce enriched sequences from the random library into the CTB3 loop in FimH, the oligonucleotides were also designed to contain an internal BamHI restriction site corresponding to amino acid position 54 in the CTB3 loop (Fig. 4). As a representative peptide from our Zn2+ binding sequences, we chose the HARAERHHQ insert from pKKJ106 and pKKJ116 for display in the CTB3 loop. The presence of this peptide in two individual clones suggests that it is involved in Zn2+ binding. The corresponding DNA segment was amplified by PCR and inserted into the BamHI site of the CTB sequence in fimH. In this way, we also altered the linker-encoded sequence from Arg-Ser to Gly-Ser. The pKKJ106 insert represents an average Zn2+ binder (Fig. 3), permitting easy detection of changes in affinity toward Zn2+ that might occur in the new scaffold background within the limits of the assay system.

FIG. 4.

Overview of plasmids encoding chimeric FimH proteins (not drawn to scale). Heterologous sequences are represented by boxes; the Zn2+-binding insert is shown by a black box, and the CTB3 sequence is shown by a gray box. A model showing the effect of using the FimH and the FimH::CTB3 scaffold systems for surface presentation of enriched peptides is also presented.

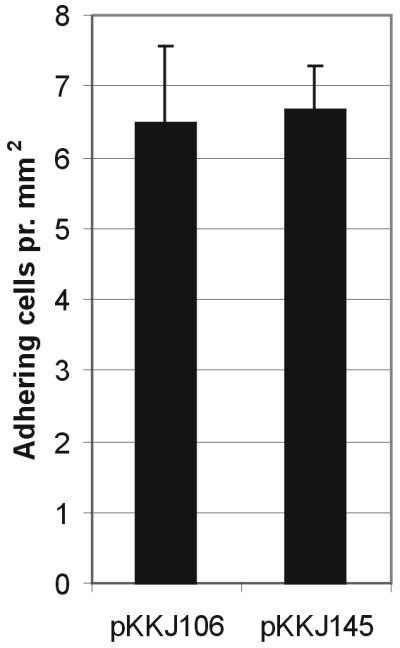

The effect of the CTB3 scaffold system on the number of fimbriae on the cell surface was examined by investigating the ability of the cells to agglutinate yeast cells. Yeast cell agglutination is a highly conserved functional property associated with FimH and can be used to monitor the expression of type 1 fimbriae. The receptor-binding activity was unaffected by the introduction of the CTB sequence. Furthermore, Western immunoblotting analysis on purified fimbriae showed no significant change in the amount of surface-located FimH for pKKJ145 compared to the control strains (data not shown). We then examined the ability of cells expressing pKKJ145 to bind Zn2+ by enumerating cells associated with Zn2+-NTA. Cells expressing pKKJ145 were observed to bind to Zn2+-NTA with a similar affinity to that of the parental clone (pKKJ106) (Fig. 5). These results strongly suggest that the Zn2+ binding is mediated by the HARAERHHQ peptide insert and is independent of the protein scaffold.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of Zn2+ binding by S1918(pPKL115) cells expressing pKKJ106 (random library clone) and pKKJ145 (random library clone with insert presented via CTB3 loop scaffold system). The average number of adhering cells per square millimeter of NTA bead is indicated for each clone, and the values are means and standard errors of means (n = 5) based on a 95% level of confidence.

DISCUSSION

Metal ions are important constituents of many natural proteins and play a role in a broad spectrum of biological processes, including electron transfer, nucleophilic catalysis, and the stabilization of protein structures. Zinc is critical for the growth of organisms and participates in the catalysis of essential metabolic reactions and in the transfer of genetic information, i.e., transcription and replication (25). On the other hand, zinc is a heavy metal and is poisonous for cells when present at higher concentrations (23). The increased use of zinc in various products such as alloys, electroplating, electronics, automotive parts, fungicides, paints, roofing, cable wrapping, and nutrition and health care products has led to a considerable accumulation of zinc in the environment and poses a potential toxicological threat to ecosystems and human health.

Biological capture systems have recently been described as being a promising tool for immobilization and removal of heavy metals from polluted water (9, 10, 15). In previous studies organisms with metal-accumulating or metal immobilization abilities have been created by the insertion of metal-binding peptides such as metallotheioneins and polyhistidines into surface-located proteins (9, 10, 15). More recently, a display of peptide libraries on the surface of microorganisms has been a powerful tool for selecting novel ligands with defined specificity (1, 3).

Natural Zn2+-binding proteins appear to chelate this metal mainly via molecular motifs encompassing cysteines and histidines (25). The use of a random library for identification of Zn2+-binding sequences offers a novel insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying metal binding without any preconceived notion of metal cation-binding motifs. Although our library contains ∼40 million individual clones, we did not select Zn2+-binding sequences with homology to any known Zn2+-binding proteins. In fact, database searches did not reveal significant homology to any reported sequences, indicating that truly novel sequences had been isolated. This suggests that a plethora of solutions to Zn2+ binding may exist and that relatively few of these are used in naturally existing proteins.

Most of the isolated sequences contained one or more histidine residues, as expected given the important role played by this amino acid in Zn2+ binding. It is a well-established fact that histidine is able to chelate divalent metal ions, as seen in a number of proteins with zinc finger motifs and metallothioneins (25). However, one sequence (pKKJ113) devoid of histidines was also identified from the library, showing that histidine is not an absolute requirement for binding to Zn2+. Indeed, cells expressing the peptide sequence of plasmid pKKJ113 mediated stronger Zn2+ binding than did cells expressing peptides containing multiple histidine residues. Furthermore, plasmid pKKJ113 displayed a very high degree of binding specificity toward Zn2+ compared to its specificity toward Ni2+. Previously, Barbas et al. (1) identified a number of Zn2+-binding peptides from a phage-displayed semisynthetic combinatorial antibody library. We did not observe any similarities between our Zn2+-binding sequences and those identified by Barbas et al. (1). This might be due to the genetic structure of the libraries and the different selection and enrichment procedures employed.

It is conceivable that the affinity of our selected clones toward zinc was in part mediated by sequences inherent in FimH that directly flank the insert region. To investigate this further, we designed a novel display scaffold system based on the CTB3 loop of CTB. By using this scaffold system to display one of our enriched metal-binding peptides, we demonstrated that Zn2+ binding seemed to be a unique property of the peptide insert rather than a combined property of the peptide insert and the carrier protein. This observation creates an opportunity to design peptide sequences independent of their protein scaffold for direct use in binding to heavy metals (4). Such metal-binding peptides could be made synthetically and easily immobilized on surfaces; they have possible uses in, for example, chip-based metal detection systems.

Metal-binding systems employing polyhistidine sequences and metallothioneins are rarely able to distinguish between different but related heavy metals such as those studied here. A high degree of binding specificity is sometimes required, e.g., for capture of a single compound. In other cases, peptides with a broad binding spectrum might be useful. The system presented here allows the selection of peptides with various degrees of binding specificity. Such clones and mutated derivatives might in the future be useful in specific sequestration and detection of heavy metals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by BIOPRO Center, part of the Danish National Strategic Environmental Program.

We thank Birthe Joergensen for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbas C F, III, Rosenblum J S, Lerner R A. Direct selection of antibodies that coordinate metals from semisynthetic combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6385–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkay T, Schaefer J. Metal and radionuclide bioremediation: issues, considerations and potentials. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:318–323. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown S. Engineered iron oxide-adhesion mutants of the Escherichia coli phage lambda receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8651–8655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown S. Metal-recognition by repeating polypeptides. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:269–272. doi: 10.1038/nbt0397-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W, Bruhlmann F, Richins R D, Mulchandani A. Engineering of improved microbes and enzymes for bioremediation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgiou G, Stathopoulos C, Daugherty P S, Nayak A R, Iverson B L, Curtiss R., III Display of heterologous proteins on the surface of microorganisms: from the screening of combinatorial libraries to live recombinant vaccines. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:29–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjaergaard K, Sorensen J K, Schembri M A, Klemm P. Sequestration of zinc oxide by fimbrial designer chelators. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:10–14. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.10-14.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemm P, Schembri M A, Stentebjerg-Olesen B, Hasman H, Hasty D L. Fimbriae: detection, purification and characterization. Methods Microbiol. 2001;27:239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotrba P, Doleckova L, de Lorenzo V, Ruml T. Enhanced bioaccumulation of heavy metal ions by bacterial cells due to surface display of short metal binding peptides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1092–1098. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1092-1098.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macaskie L E. An immobilized cell bioprocess for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous flows. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 1990;49:357–379. doi: 10.1002/jctb.280490408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsunaga T, Takeyama H, Nakao T, Yamazawa A. Screening of marine microalgae for bioremediation of cadmium-polluted seawater. J Biotechnol. 1999;70:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merritt E A, Sarfaty S, Van den A F, L'Hoir C, Martial J A, Hol W G. Crystal structure of cholera toxin B-pentamer bound to receptor GM1 pentasaccharide. Protein Sci. 1994;3:166–175. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pallesen L, Poulsen L K, Christiansen G, Klemm P. Chimeric FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae: a bacterial surface display system for heterologous sequences. Microbiology. 1995;141:2839–2848. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-11-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pazirandeh M, Wells B M, Ryan R L. Development of bacterium-based heavy metal biosorbents: enhanced uptake of cadmium and mercury by Escherichia coli expressing a metal binding motif. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4068–4072. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4068-4072.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez A, Ballester A, Blazquez M L, Gonzalez F, Munoz J, Hammaini A. Biosorption of copper and zinc by Cymodocea nodosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schembri M A, Kjaergaard K, Klemm P. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals by fimbrial designer adhesins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:363–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schembri M A, Klemm P. Heterobinary adhesins based on the Escherichia coli FimH fimbrial protein. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1628–1633. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1628-1633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schembri M A, Pallesen L, Connell H, Hasty D L, Klemm P. Linker insertion analysis of the FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae in an Escherichia coli fimH-null background. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:257–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shoham M, Scherf T, Anglister J, Levitt M, Merritt E A, Hol W G. Structural diversity in a conserved cholera toxin epitope involved in ganglioside binding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:841–848. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silver S, Walderhaug M. Gene regulation of plasmid- and chromosome-determined inorganic ion transport in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:195–228. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.195-228.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stentebjerg-Olesen B, Pallesen L, Jensen L B, Christiansen G, Klemm P. Authentic display of a cholera toxin epitope by chimeric type 1 fimbriae: effects of insert position and host background. Microbiology. 1997;143:2027–2038. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vallee B L, Auld D S. Zinc coordination, function, and structure of zinc enzymes and other proteins. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5647–5659. doi: 10.1021/bi00476a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J L. Zn biosorption by Rhizopus arrhizus and other fungi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;51:686–693. [Google Scholar]