Abstract

Cerium oxide nanoparticles, also known as nanoceria, possess antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities in animal models of inflammatory disorders, such as sepsis. However, it remains unclear how nanoceria affect cellular superoxide fluxes in macrophages, a critical type of cells involved in inflammatory disorders. Using human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages, we showed that nanoceria at 1–100 μg/ml potently reduced superoxide flux from the mitochondrial electron transport chain (METC) in a concentration-dependent manner. The inhibitory effects of nanoceria were also shown in succinate-driven mitochondria isolated from the macrophages. Furthermore, nanoceria markedly mitigated the total intracellular superoxide flux in the macrophages. These data suggest that nanoceria could readily cross the plasma membrane and enter the mitochondrial compartment, reducing intracellular superoxide fluxes in unstimulated macrophages. In macrophages undergoing respiratory burst, nanoceria also strongly reduced superoxide flux from the activated macrophage plasma membrane NADPH oxidase (NOX) in a concentration-dependent manner. Token together, the results of the present study demonstrate that nanoceria can effectively diminish superoxide fluxes from both METC and NOX in human macrophages, which may have important implications for nanoceria-mediated protection against inflammatory disease processes.

Keywords: Nanoceria, Cerium oxide, Macrophage, Mitochondrial electron transport chain, NADPH oxidase, Superoxide

1. Introduction

Cerium is a rare earth element of the lanthanide series. The oxide form (CeO2) is used as a support material in automotive catalysis. Over the past two decades, cerium oxide nanoparticles, or nanoceria in short, have been investigated extensively as a promising antioxidant nanomaterial with a relatively favorable safety profile for the intervention of disease processes involving an oxidative and inflammatory mechanism in animal models (reviewed in [1]). The notable examples include nanoceria-mediated cardioprotection in a transgenic mouse model of cardiomyopathy [2], survival benefit in a cecal peritonitis-induced sepsis model in rats [3], and neuroprotection in 6-hydroxydopamine-induced parkinsonism in rats [4]. The beneficial effects observed in various animal models of human diseases are believed to result primarily from the catalytic scavenging capacity of nanoceria towards a range of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially superoxide [5–7]. Indeed, nanoceria have been shown to scavenge superoxide (O2.−)via the redox switch between Ce3+ and Ce4+ [5, 8] (Reactions 1 and 2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Because of the above redox properties, nanoceria have been suggested to possess a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic activity, i.e., the autocatalytic dismutation of superoxide [8]. Moreover, the reaction rate constant for nanoceria-catalyzed dismutation of superoxide may exceed that determined for the native enzyme SOD [8]. Besides having an SOD activity, nanoceria may also possess a redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity [9]. Evidence also suggested that nanoceria might be able to catalytically reduce nitrogen dioxide (NO2) to nitric oxide (NO), and NO to N2 through redox switch between Ce3+ and Ce4+ [10, 11].

Superoxide, as a precursor of many other ROS as well as reactive nitrogen species (RNS), has been implicated in various disease processes, including cardiovascular disorders, neurodegeneration, and sepsis, to name a few (reviewed in [12]). Two major sources of cellular superoxide production are the mitochondrial electron transport chain (METC) in resting cells and the NADPH oxidases (also known as NOX enzymes) in activated cells, especially inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages) [12]. In this regard, superoxide derived from these sources, especially METC, has been shown to be a major player in causing oxidative and inflammatory disease processes [13, 14]. Hence, studying the impact of antioxidant-based strategies on cellular superoxide fluxes from METC as well as NOX enzymes can provide important insights into the efficacy, in disease intervention, of antioxidant-based modalities, including nanoceria. Accordingly, in the present study, we determined the effects of nanoceria on superoxide fluxes from both METC and NOX in macrophages differentiated from human monoblastic ML-1 cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

MitoSOX, RPMI-1640 medium, penicillin, streptomycin, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and cell culture flasks and other plastic wares were from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). 5-(Diethoxyphosphoryl)-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DEPMPO) was from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). Cerium oxide nanoparticles (nanoceria, < 5 nm), lucigenin, coelenterazine hcp, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), and all other chemicals and agents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Culture and Differentiation of ML-1 cells to macrophages

Human monoblastic ML-1 cells were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 10% FBS in tissue culture flasks at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The differentiation to macrophages was initiated by incubation of ML-1 cells (3 × 105/ml) with 0.3 ng/ml TPA for 3 days, and then the medium was removed. The cells were fed with fresh media without further addition of TPA. The cells were cultured for another 3 days. Cells at this time point were characteristic of human macrophages [15] and were harvested for further experiments.

2.3. Isolation of mitochondria from macrophages

Mitochondria were isolated from the freshly harvested ML-1 cell-derived macrophages as described by us before [15].The mitochondrial protein was measured with Bio-Rad protein assay dye based on the method of Bradford [16] with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The isolated mitochondria exhibited normal respiration and coupled oxidative phosphorylation, indicating the maintenance of the integrity of mitochondrial membrane potential [17]. In addition, our previous studies have demonstrated functional electron transport through all METC complexes (i.e., complexes I–IV) with mitochondria isolated from ML-1 cell-derived macrophages [18].

2.4. Real-time detection of intramitochondrial superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages

Intramitochondrial superoxide flux in resting macrophages was detected by lucigenin-derived chemiluminescence (LDCL) described by us before [15]. Briefly, unstimulated macrophages (2 × 105 cells) were suspended in 1 ml of air-saturated complete PBS (PBS supplemented with 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.7 mM CaCl2, and 0.1% glucose). The LDCL response was initiated by adding 5 μM lucigenin, and the real-time photon emission (counts per minute) was captured continuously for 60 min at 37°C using an ultrasensitive LB9505 multichannel luminometer (Berthold, Wildbad, Germany). To determine the effects of the nanoparticles, nanoceria were added to the cell suspension immediately before the addition of lucigenin. Hence, the total incubation time with nanoceria was 60 min. Likewise, to further confirm the source of cellular superoxide, METC inhibitors, mitochondrial uncoupler (FCCP), or known superoxide scavengers were also added immediately before the addition of lucigenin. The total counts of photons emitted during the 60 min were calculated as integrated LDCL response which indicated the total amounts of mitochondrial superoxide flux in the resting macrophages during the 60-min period. It is worth noting that lucigenin at 5 μM has been shown to be a reliable probe for detecting biological superoxide in human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages [15, 17]. In these cells at resting conditions, LDCL (with 5 μM lucigenin) specifically detects intramitochondrial superoxide, and any artifact due to potential lucigenin redox cycling is completely eliminated [15, 17]. On the other hand, very high concentrations (e.g., 50–500 μM) of lucigenin commonly used in detecting biological superoxide by many investigators may cause artifacts depending on the nature of the biological systems studied [19]. Nevertheless, in addition to lucigenin, other probes (e.g., coelenterazine hcp and DEPMPO) were also used in the present study to determine cellular superoxide and the effects of nanoceria.

2.5. Real-time detection of METC-derived superoxide flux in mitochondria isolated from unstimulated macrophages

METC-derived superoxide flux in isolated mitochondria driven by succinate was detected by LDCL as described by us before [17]. Briefly, the reaction mixture contained 30 μg/ml of mitochondria in the presence of 5 mM succinate in 1 ml of air-saturated respiration buffer (70 mM sucrose, 220 mM mannitol, 2 mM Hepes, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4). The LDCL response was initiated by adding 5 μM lucigenin and the real-time the real-time photon emission was captured and analyzed as described above (Section 2.4). To determine the effects of the nanoparticles, nanoceria were added to the mitochondrial suspension immediately before the addition of lucigenin. Likewise, to further confirm the METC dependency of superoxide flux, METC inhibitors or known superoxide scavengers were also added immediately before the addition of lucigenin.

2.6. Real-time detection of total intracellular superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages

Lucigenin is a cation and accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix due to the negative charge of the mitochondrial inner membrane [17, 20]. As such, LDCL detects specifically intramitochondrial superoxide flux [17]. On the other hand, coelenterazine hcp, another superoxide-detecting chemiluminescent probe, is not charged and distributes evenly throughout the intracellular compartments. Hence, coelenterazine hcp-derived CL (CDCL) can be used to detect total cellular superoxide flux [21, 22]. To detect the total intracellular superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages, the cells (2 × 105 cells) were suspended in 1 ml of air-saturated complete PBS. The CDCL response was initiated by adding 1 μM coelenterazine hcp and the real-time photon emission was captured and analyzed as described above (Section 2.4). To determine the effects of the nanoparticles, nanoceria were added to the cell suspension immediately before the addition of coelenterazine hcp. Likewise, to verify intracellular source of superoxide flux, mitochondrial uncoupler (FCCP) or known superoxide scavengers were also added immediately before the addition of coelenterazine hcp.

2.7. Real-time detection of NOX-derived superoxide flux in macrophages undergoing respiratory burst

LDCL in the presence of rotenone plus myxothiazol—also known as METC-independent LDCL—was used to detect NOX-derived superoxide flux in macrophages stimulated with TPA (i.e., macrophages undergoing respiratory burst). Briefly, macrophages (2 × 105 cells) were suspended in 1 ml complete PBS containing 10 μM rotenone and 10 μM myxothiazol and 5 μM lucigenin. The METC-independent LDCL response was initiated by adding TPA and the real-time photon emission was captured and analyzed as described above (Section 2.4). To determine the effects of the nanoparticles, nanoceria were added to the cell suspension immediately before the addition of TPA. Likewise, to confirm the NADPH oxidase dependency of the superoxide flux, 10 μM diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a potent inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, was added immediately before the addition of TPA.

2.8. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spin-trapping detection of extracellular superoxide flux from NOX activation in macrophages undergoing respiratory burst

DEPMPO-based spin trapping assay was used to detect extracellular superoxide flux in TPA-stimulated macrophages as described by us before [15]. In brief, 2 × 105 macrophages were suspended in complete PBS (0.1 ml) containing 10 mM DEPMPO followed by adding 0.1 μg TPA. To determine the effects of the nanoparticles, nanoceria were added to the cell suspension immediately before the addition of TPA. Likewise, to confirm the superoxide specificity, CuZnSOD (100 units/ml) was added immediately before the addition of TPA. The sample was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Immediately after the incubation, the cell suspension was transferred into a capillary tube for detection of the DEPMPO-superoxide adduct using an EPR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) under the following conditions: modulation frequency, 100 kHz; microwave power, 20 mW; and microwave frequency, 9.78 GHz.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SD from at least three separate experiments unless otherwise indicated. Differences between mean values of multiple groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Student–Newman–Keuls test. Differences between two groups were analyzed by Student’s t test. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of nanoceria on intramitochondrial superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages

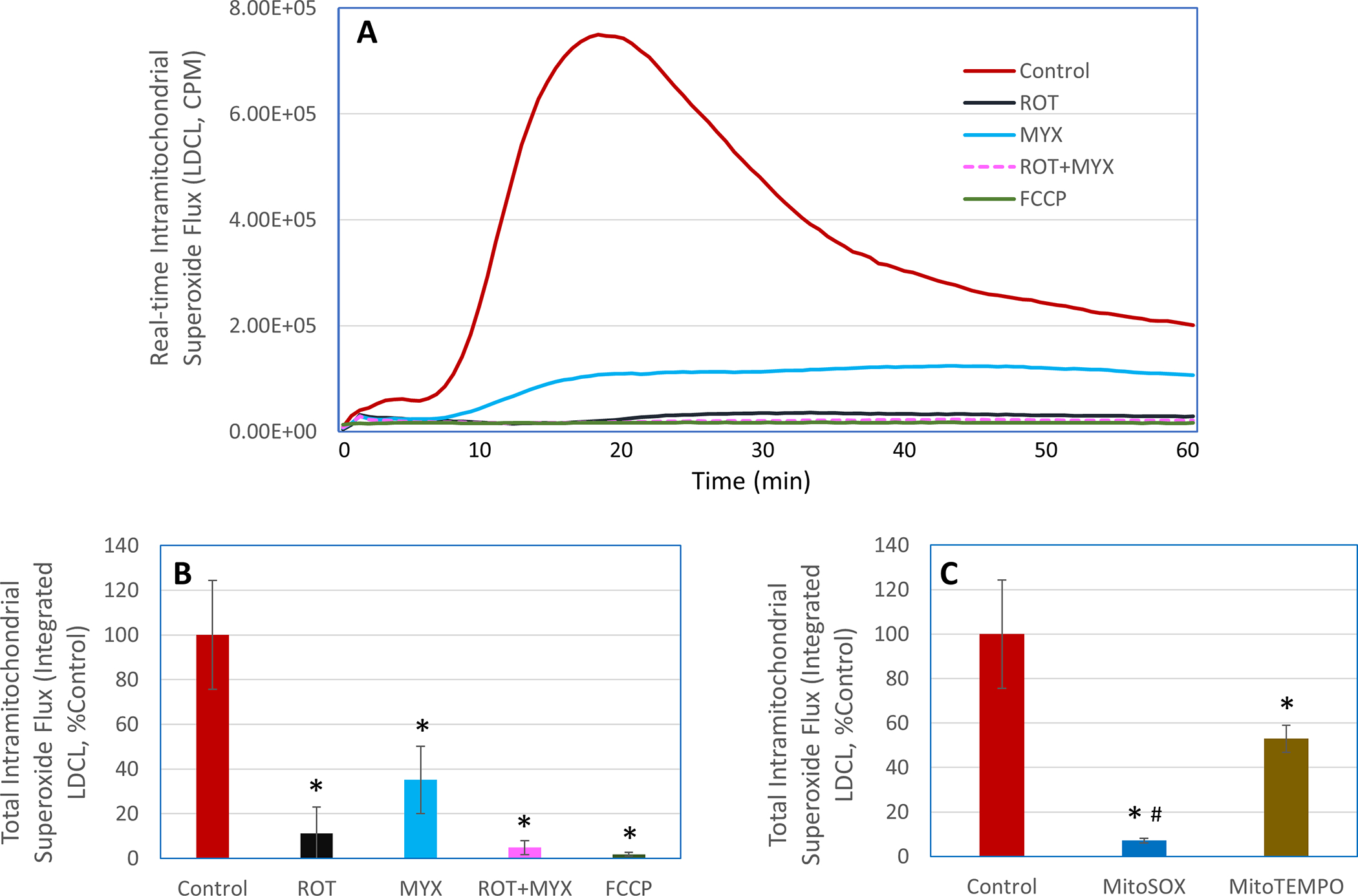

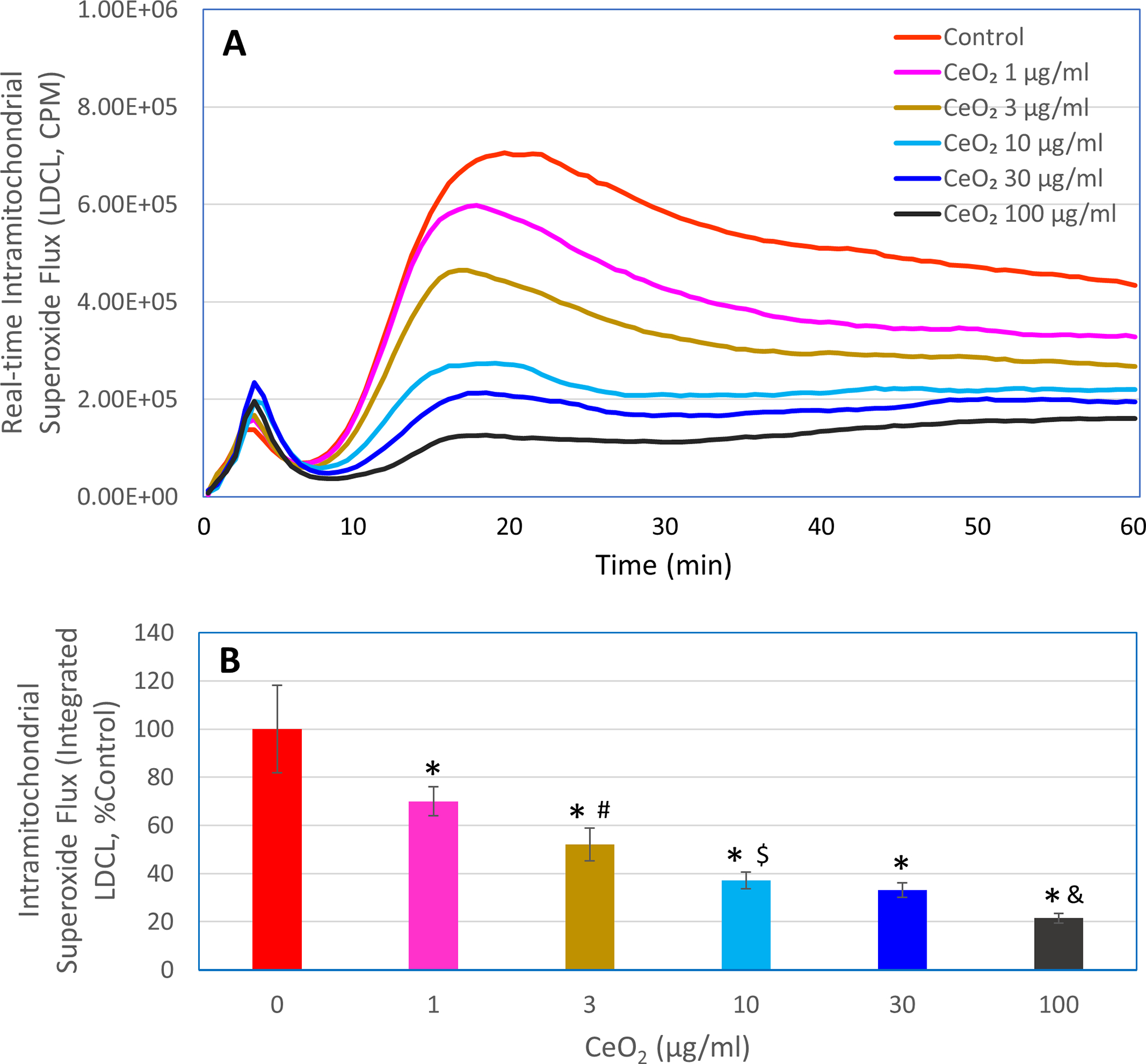

METC is a major source of cellular superoxide in unstimulated macrophages [23]. Accordingly, we first used the ultrasensitive LDCL technique to determine the specific effects of nanoceria on superoxide flux from the METC under basal conditions. As shown in Figure 1, in unstimulated macrophages, LDCL was completed blocked by METC inhibitors (10 μM rotenone, a complex I inhibitor, plus 10 μM myxothiazol, a complex III inhibitor) or uncoupler, carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 10 μM), or 5 μM MitoSOX (a mitochondrial superoxide quencher), conforming the specificity of LDCL for detecting intramitochondrial ETC-derived superoxide flux in resting macrophages. MitoTEMPO, another mitochondrial superoxide quencher, at 50 μM also caused an about 50% reduction in LDCL (Figure 1C). Incubation of macrophages with nanoceria (1–100 μg/ml) resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction in LDCL (Figure 2), suggesting that nanoceria could potently reduce intramitochondrial superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages. This finding also suggests that nanoceria could not only cross the plasma membrane but also enter the mitochondrial compartment in intact macrophages. An early study by Dowding et al. showed that nanoceria are internalized by neurons and accumulate at the mitochondrial compartment [24]. The native positive charges of the nanoceria may facilitate their mitochondrial localization. Addition of an extra positively charged group to nanoceria further enhances their mitochondrial localization [25], pointing to the feasibility for the fine nanoparticles (< 5 nm) to cross mitochondrial membranes. To further investigate this possibility, we conducted experiments with isolated mitochondria (see Section (3.2 below).

Figure 1. Detection, by LDCL, of intramitochondrial METC-derived superoxide flux in unstimulated human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages.

LDCL response was detected in the macrophages in the presence or absence of rotenone (ROT), myxothazol (MYX), combination of ROT and MYX, FCCP, MitoSOX, or MitoTEMPO. The concentration for ROT, MYX, and FCCP was 10 μM, for MitoSOX was 5 μM, and for MitoTEMPO was 50 μM. Panel A shows real-time photon emission over 60 min and panels B and C show total photon emission over 60 min. *, p < 0.05 versus respective Control; #, p < 0.05 versus MitoTEMPO.

Figure 2. Effects of nanoceria on intramitochondrial METC-derived superoxide flux in unstimulated human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages.

LDCL response was detected in the macrophages in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of nanoceria (CeO2, 1–100 μg/ml). Panel A shows real-time photon emission over 60 min and panel B shows total photon emission over 60 min. *, p < 0.05 versus 0 μg/ml CeO2; #, p < 0.05 versus 1 μg/ml CeO2; $, p < 0.05 versus 3 μg/ml CeO2; &, p < 0.05 versus 30 μg/ml CeO2.

It should be noted that the highly pure and fine nanoceria particles (< 5 nm) at the concentrations used in the present study did not affect the viability of the ML-1 cell-derived macrophages (data not shown). As mentioned above, when used at effective doses for disease intervention in animal models, nanoceria showed very favorable safety profile (reviewed in [1]). Studies by others also reported that in cultured cells, including murine and human macrophages, incubation with nanoceria at concentrations up to 100 μg/ml for 24 to 48 h did not induce significant cytotoxicity [26, 27].

3.2. Effects of nanoceria on METC-derived superoxide flux in isolated mitochondria driven by succinate

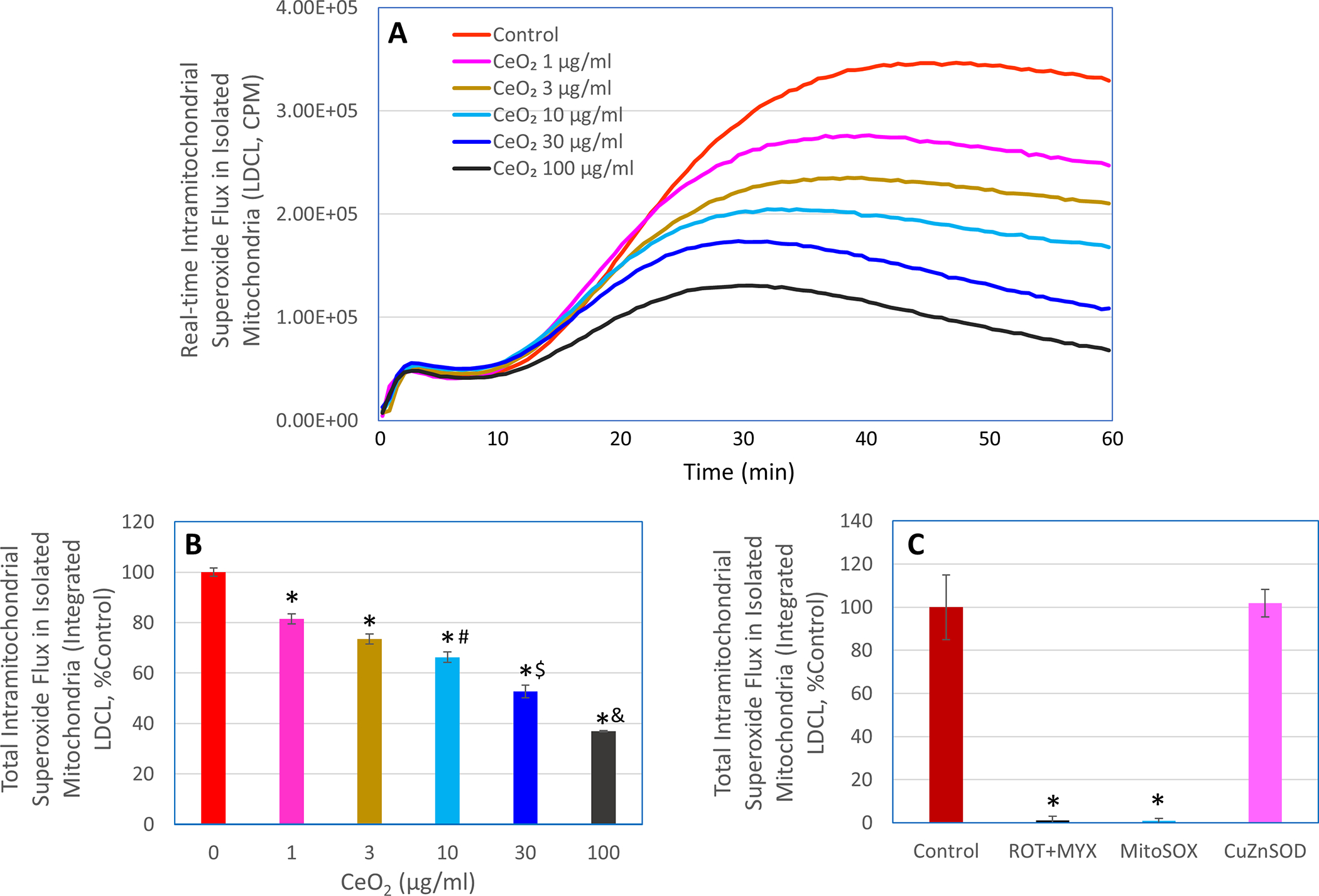

Isolated mitochondria were used to further investigate the effects of nanoceria on METC-derived superoxide flux. Like what observed in intact macrophages, nanoceria also decreased superoxide flux, as determined by LDCL, in succinate-driven mitochondria isolated from macrophages (Figure 3). In contrast, addition of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD) did not affect the LDCL response in succinate-driven mitochondria, suggesting that unlike CuZnSOD, nanoceria could readily enter the mitochondria, thereby reducing METC-derived superoxide flux. On the other hand, similar to what observed with intact macrophages, either combination of rotenone (10 μM) and myxothiazol (10 μM) or 5 μM MitoSOX completely blocked the LDCL in succinate-driven mitochondria. This observation is in line with early findings that LDCL specifically detects intramitochondrial superoxide flux [17, 28].

Figure 3. Effects of nanoceria on METC-derived superoxide flux in isolated mitochondria driven by succinate.

LDCL response was detected in isolated succinate-driven mitochondria in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of nanoceria (CeO2, 1–100 μM), rotenone plus myxothiazol (ROT+MYX, 10 μM each), MitoSOX (5 μM), or CuZnSOD (100 units/ml). Panel A shows real-time photon emission over 60 min and panels B and C show total photon emission over 60 min. In panel B, *, p < 0.05 versus 0 μg/ml CeO2; #, p < 0.05 versus 3 μg/ml CeO2; $, p < 0.05 versus 10 μg/ml CeO2; &, p < 0.05 versus 30 μg/ml CeO2. In panel C, *, p < 0.05 versus Control.

Collectively, the above findings with both intact macrophages and isolated mitochondria suggest that nanoceria could potently reduce METC-derived superoxide flux. The findings also indicate that nanoceria could readily enter the cells and accumulate in the mitochondrial compartment though the mechanisms underlying nanoceria transporting across biomembranes remain to be elucidated. Nevertheless, the ability of nanoceria to enter mitochondria and diminish METC-derived superoxide flux may explain the efficacy of this nanomaterial in protecting against mitochondrial oxidative stress in experimental models [24, 29].

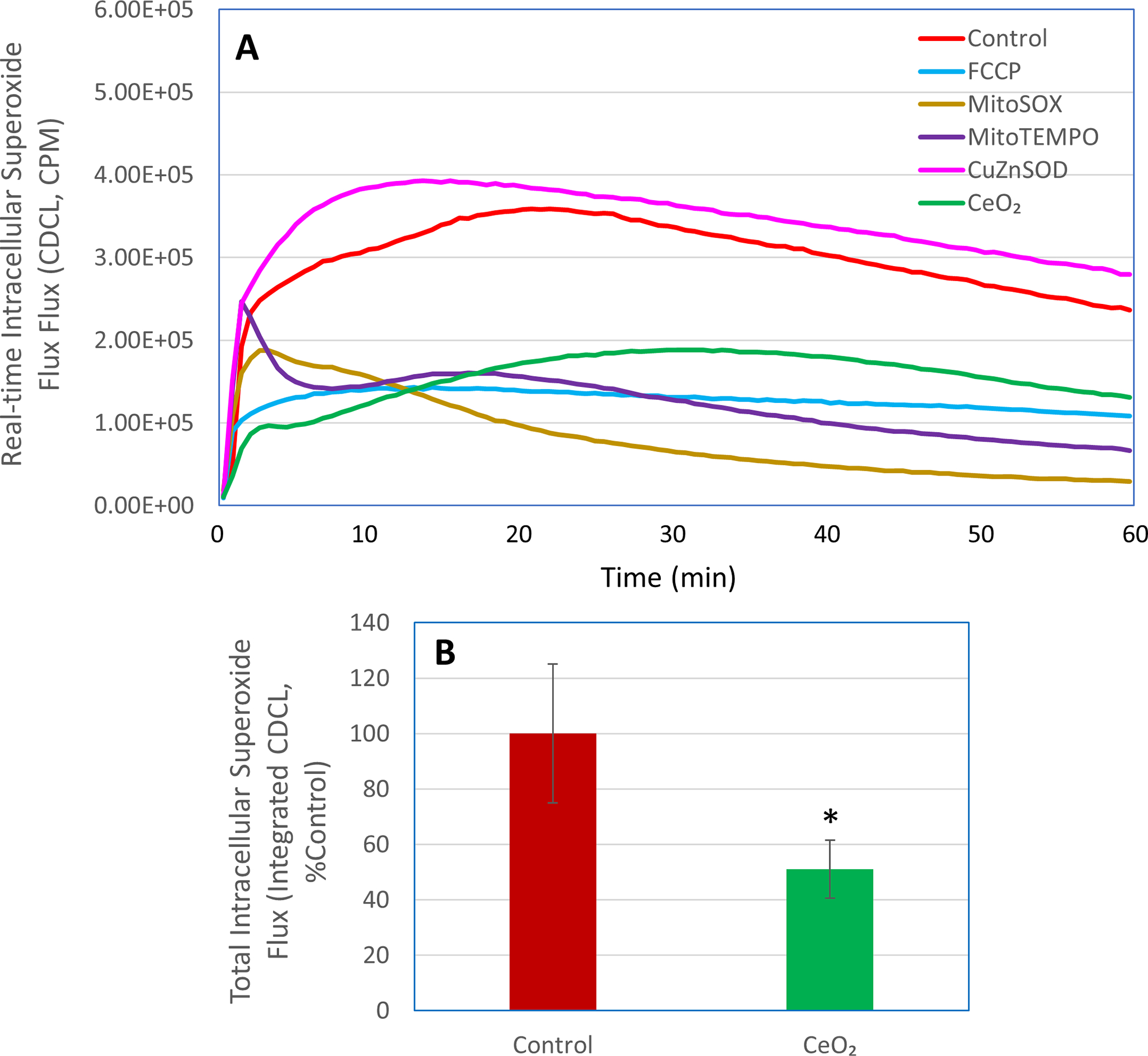

3.3. Effects of nanoceria on total intracellular superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages

Because LDCL selectively accumulates within the mitochondrial compartment and as such specifically detects intramitochondrial METC-derived superoxide flux, we next used a different chemiluminescent probe-based technique to determine the effects of nanoceria on total intracellular superoxide flux in unstimulated macrophages. In this regard, the superoxide probe coelenterazine hcp freely crosses cell membranes and evenly distributes across various intracellular compartments due to its non-charged nature. As shown in Figure 4, the coelenterazine hcp-dependent CL (CDCL) response in unstimulated macrophages was greatly reduced by FCCP (10 μM), MitoSOX (5 μM), MitoTEMPO (50 μM), or nanoceria (30 μg/ml). While FCCP and MitoSOX completely blocked the LDCL (Figures 1 and 3), they blocked CDCL response by about 60–70% (Figure 4A). This finding indicates that in unstimulated macrophages, although METC is a major source of cellular superoxide, other intracellular sources also contribute to the total superoxide flux detected by the CDCL. Notably, nanoceria at 30 μg/ml reduced the total intracellular superoxide flux by about 50% (Figure 4B). The failure of extracellularly added CuZnSOD to affect CDCL further confirms that CDCL detects total intracellular superoxide flux.

Figure 4. Effects of nanoceria on total intracellular superoxide flux in unstimulated human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages.

CDCL response was detected in the macrophages in the presence or absence of FCCP (10 μM), MitoSOX (5 μM), MitoTEMPO (50 μM), CuZnSOD (100 units/ml), or nanoceria (CeO2, 30 μg/ml). Panel A shows real-time photon emission over 60 min and panel B shows total photon emission over 60 min. *, p < 0.05 versus Control.

3.4. Effects of nanoceria on NOX-derived superoxide flux in macrophages undergoing respiratory burst

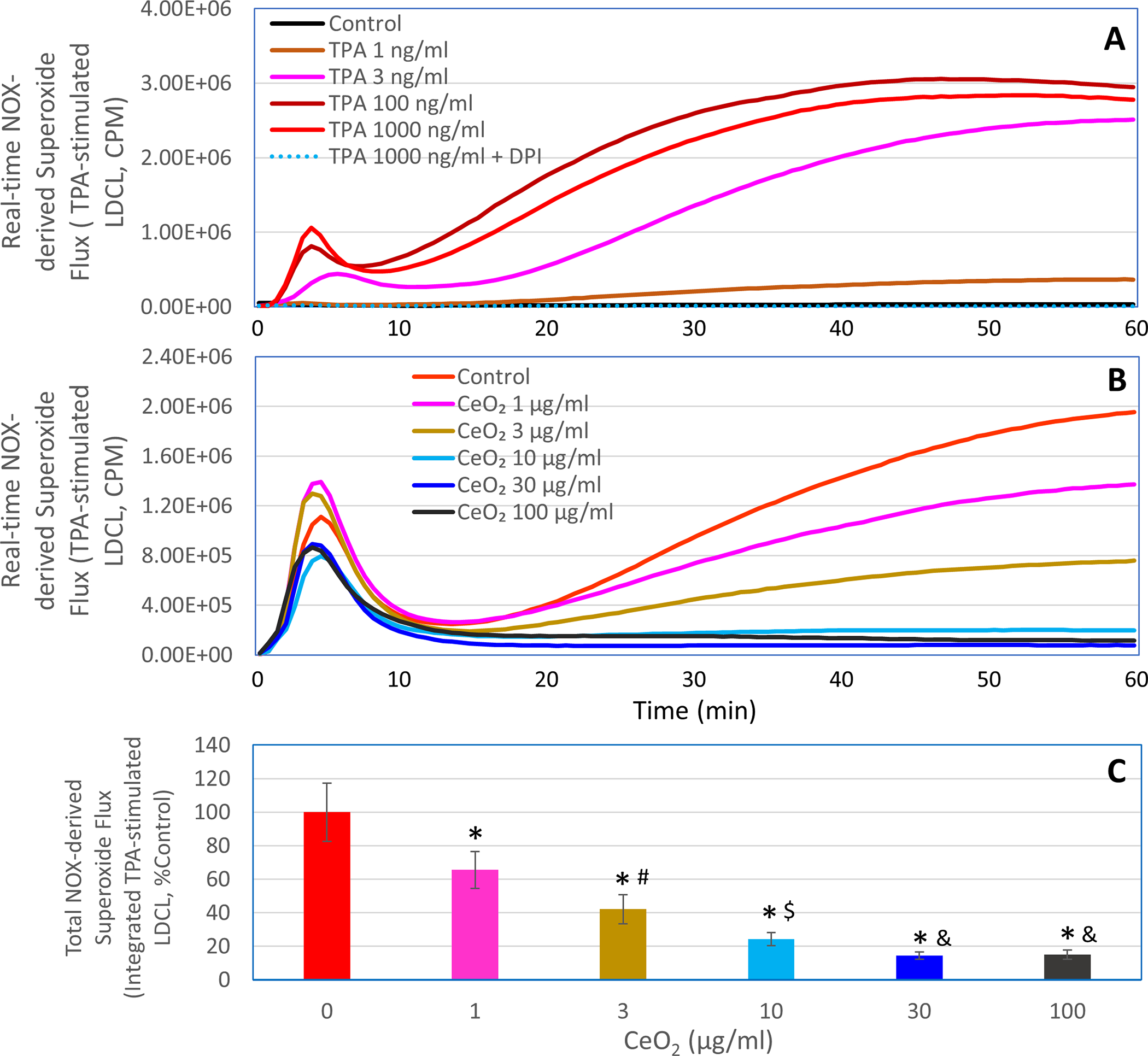

While METC is a major source of cellular superoxide in resting macrophages, macrophages undergoing respiratory burst generate large amounts of superoxide from the plasma membrane NOX enzyme complex, and the NOX-derived superoxide plays a critical role in innate immunity (e.g., killing of invading pathogens) as well as in causing inflammatory tissue injury [30]. In this study, we therefore also determined the effects of nanoceria on NOX-derived superoxide flux in macrophages stimulated by TPA, a protein kinase C activator [31]. As shown in Figure 5A, when macrophages pretreated with rotenone (10 μM) plus myxothiazol (10 μM) to block the METC-derived superoxide, addition of TPA caused a concentration-dependent release of superoxide as detected by LDCL. Hence, in the presence of rotenone and myxothiazol, the LDCL specifically detects superoxide flux from the TPA-activated NOX. TPA-induced respiratory burst and superoxide production from the plasma membrane NOX enzyme complex is a well characterized phenomenon in phagocytic cells [31]. The complete inhibition of TPA-induced LDCL by the potent NOX inhibitor DPI (Figure 5A) further confirmed the NOX dependency of the superoxide flux during respiratory burst. As 3 ng/ml TPA caused markedly increased release of superoxide from the NOX, we chose this TPA concentration for subsequent experiments to determine the effects of nanoceria on NOX-derived superoxide flux. As shown in Figure 5B and 5C, addition of nanoceria (1–100 μg/ml) immediately before TPA dramatically reduced the NOX-derived superoxide flux in a concentration-dependent manner. This result suggests that nanoceria could not only potently reduce intramitochondrial superoxide flux in resting macrophages, but also greatly diminish NOX-derived superoxide flux in macrophages undergoing respiratory burst.

Figure 5. Effects of nanoceria on NOX-derived superoxide flux in human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages undergoing respiratory burst, as detected by LDCL.

In panel A, LDCL response was detected in the rotenone/myxothiazol-treated macrophages in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations (1–1000 ng/ml) of TPA or 1000 ng/ml TPA plus 10 μM DPI. In panels B and C, LDCL response was detected in the rotenone/myxothiazol-treated macrophages stimulated with 3 ng/ml TPA in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of nanoceria (CeO2, 1–100 μg/ml). Panels A and B show real-time photon emission over 60 min and panel C shows total photon emission over 60 min. *, p < 0.05 versus 0 μg/ml CeO2; #, p < 0.05 versus 1 μg/ml CeO2; $, p < 0.05 versus 3 μg/ml CeO2; &, p < 0.05 versus 10 μg/ml CeO2.

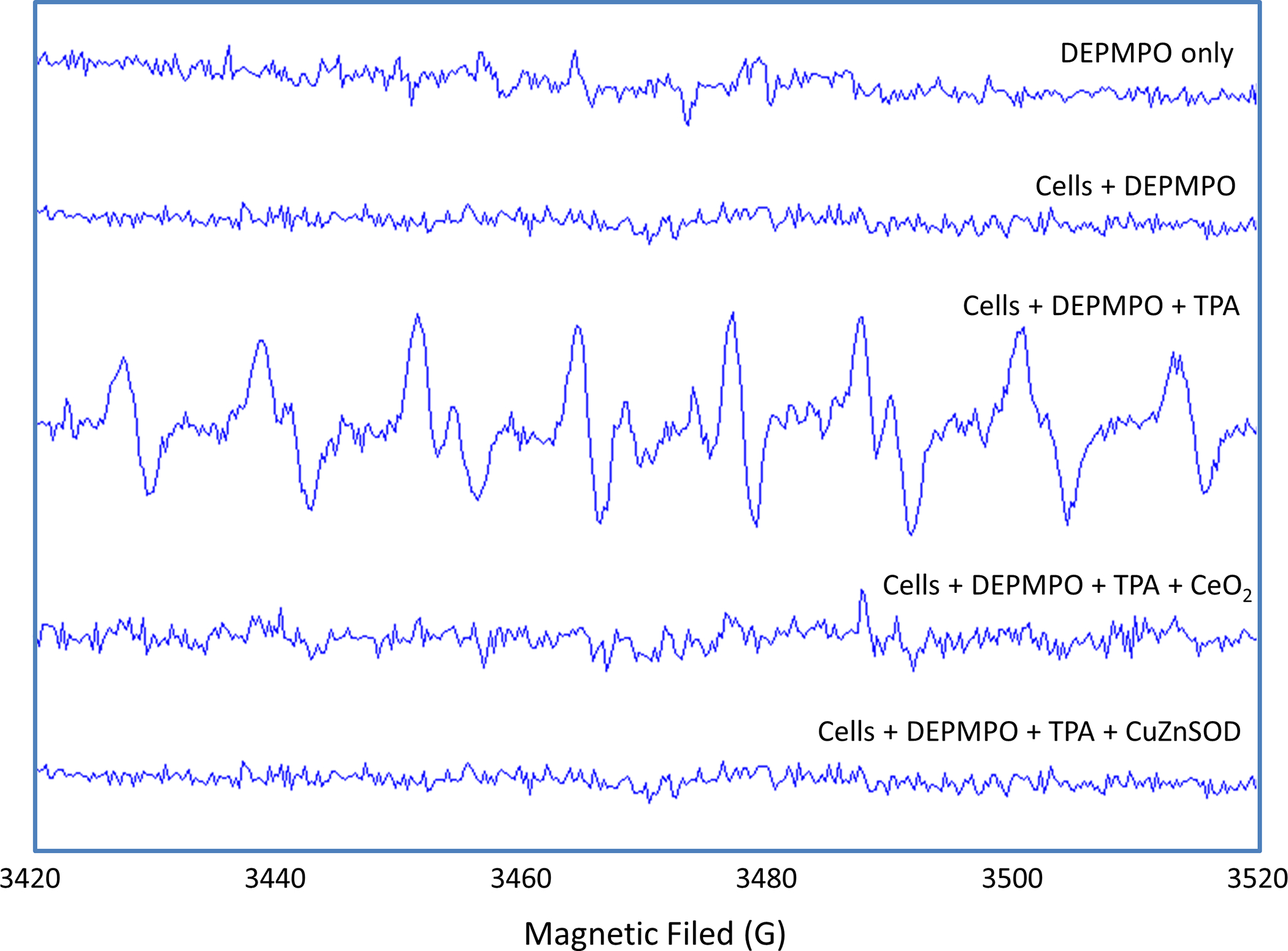

To further investigate the effects of nanoceria on NOX-derived superoxide flux, we carried out the DEPMPO-based EPR spin-trapping study. EPR technique is considered the most specific way of free radical detection [32]. However, the commonly used spin traps, including DEPMPO cannot readily cross cell membranes and as such are typically used to detect only extracellular superoxide or superoxide generated in a cell-free system [32]. Nevertheless, we applied DEPMPO-spin trapping to further demonstrate the ability of nanoceria to reduce extracellular superoxide flux from NOX activation. As shown in Figure 6, TPA-stimulated macrophages released superoxide which was trapped by DEPMPO to form a DEPMPO-superoxide spin adduct. The formation of this spin adduct was completed prevented in the presence of nanoceria (100 μg/ml) or CuZnSOD (100 units/ml; used as a positive control for reducing superoxide flux). The EPR data along with the data presented in Figure 5 collectively demonstrated a remarkable capacity for nanoceria to reduce NOX-derived superoxide flux in activated macrophages.

Figure 6. Effects of nanoceria on NOX-derived superoxide flux in human ML-1 cell-derived macrophages undergoing respiratory burst, as detected by DEPMPO-spin trapping.

10 mM TEPMPO was incubated in complete PBS only (first spectrum from the top), with unstimulated macrophages (second spectrum), with macrophages stimulated by TPA (3rd spectrum), with macrophages stimulated by TPA in the presence of nanoceria (CeO2,100 μg/ml; 4th spectrum), or with macrophages stimulated by TPA in the presence of CuZnSOD (100 units/ml; 5th spectrum). The spectra are representative of two separate experiments.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate the feasibility of using nanoceria to potently decrease superoxide fluxes from mitochondrial respiration at rest as well as respiratory burst upon TPA stimulation in human macrophages. The findings may provide mechanistic insights into the effectiveness of nanoceria in protecting against disease processes involving dysregulated superoxide production by macrophages or other types of cells.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM124652). The EPR facility used in this study was supported by an Institutional Development Grant (IDG-1018) from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center (Research Triangle Park, NC). The Berthold LB9505 luminometer was provided by Dr. Michael A. Trush from The Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD).

Funding:

This study was supported in part by a grant (GM124652) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and an Institutional Development Grant (IGD-1018) from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center, Research triangle Park, NC.

Abbreviations used:

- CDCL

coelenterazine hcp-derived chemiluminescence

- DEPMPO

5-(diethoxyphosphoryl)-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone

- LDCL

lucigenin-derived chemiluminescence

- METC

mitochondrial electron transport chain

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Ethical approval: Not applicable. This work does not involve animals or human subjects.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Casals E, Zeng M, Parra-Robert M, Fernandez-Varo G, Morales-Ruiz M, Jimenez W, Puntes V and Casals G (2020) Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: Advances in Biodistribution, Toxicity, and Preclinical Exploration. Small 16:e1907322. doi: 10.1002/smll.201907322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niu J, Azfer A, Rogers LM, Wang X and Kolattukudy PE (2007) Cardioprotective effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles in a transgenic murine model of cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 73:549–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selvaraj V, Manne ND, Arvapalli R, Rice KM, Nandyala G, Fankenhanel E and Blough ER (2015) Effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on sepsis induced mortality and NF-kappaB signaling in cultured macrophages. Nanomedicine (Lond) 10:1275–88. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegazy MA, Maklad HM, Samy DM, Abdelmonsif DA, El Sabaa BM and Elnozahy FY (2017) Cerium oxide nanoparticles could ameliorate behavioral and neurochemical impairments in 6-hydroxydopamine induced Parkinson’s disease in rats. Neurochem Int 108:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heckert EG, Karakoti AS, Seal S and Self WT (2008) The role of cerium redox state in the SOD mimetic activity of nanoceria. Biomaterials 29:2705–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Shen X, Gao X and Zhao Y (2019) Simultaneous enzyme mimicking and chemical reduction mechanisms for nanoceria as a bio-antioxidant: a catalytic model bridging computations and experiments for nanozymes. Nanoscale 11:13289–13299. doi: 10.1039/c9nr03473k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Codo AC, Davanzo GG, Monteiro LB, de Souza GF, Muraro SP, Virgilio-da-Silva JV, Prodonoff JS, Carregari VC, de Biagi Junior CAO, Crunfli F, Jimenez Restrepo JL, Vendramini PH, Reis-de-Oliveira G, Bispo Dos Santos K, Toledo-Teixeira DA, Parise PL, Martini MC, Marques RE, Carmo HR, Borin A, Coimbra LD, Boldrini VO, Brunetti NS, Vieira AS, Mansour E, Ulaf RG, Bernardes AF, Nunes TA, Ribeiro LC, Palma AC, Agrela MV, Moretti ML, Sposito AC, Pereira FB, Velloso LA, Vinolo MAR, Damasio A, Proenca-Modena JL, Carvalho RF, Mori MA, Martins-de-Souza D, Nakaya HI, Farias AS and Moraes-Vieira PM (2020) Elevated Glucose Levels Favor SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Monocyte Response through a HIF-1alpha/Glycolysis-Dependent Axis. Cell Metab 32:437–446 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korsvik C, Patil S, Seal S and Self WT (2007) Superoxide dismutase mimetic properties exhibited by vacancy engineered ceria nanoparticles. Chem Commun (Camb):1056–8. doi: 10.1039/b615134e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirmohamed T, Dowding JM, Singh S, Wasserman B, Heckert E, Karakoti AS, King JE, Seal S and Self WT (2010) Nanoceria exhibit redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity. Chem Commun (Camb) 46:2736–8. doi: 10.1039/b922024k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan M, Parker SC and Watson GW (2006) CeO2 catalysed conversion of CO, NO2 and NO from first principles energetics. Phys Chem Chem Phys 8:216–8. doi: 10.1039/b514782d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolan M, Parker SC and Watson GW (2006) Reduction of NO2 on ceria surfaces. J Phys Chem B 110:2256–62. doi: 10.1021/jp055624b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins RZ (2016) Superoxide in Biology and Medicine: An Overview. Reactive Oxygen Species 1:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickel AG, von Hardenberg A, Hohl M, Loffler JR, Kohlhaas M, Becker J, Reil JC, Kazakov A, Bonnekoh J, Stadelmaier M, Puhl SL, Wagner M, Bogeski I, Cortassa S, Kappl R, Pasieka B, Lafontaine M, Lancaster CR, Blacker TS, Hall AR, Duchen MR, Kastner L, Lipp P, Zeller T, Muller C, Knopp A, Laufs U, Bohm M, Hoth M and Maack C (2015) Reversal of Mitochondrial Transhydrogenase Causes Oxidative Stress in Heart Failure. Cell Metab 22:472–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills EL, Kelly B, Logan A, Costa ASH, Varma M, Bryant CE, Tourlomousis P, Dabritz JHM, Gottlieb E, Latorre I, Corr SC, McManus G, Ryan D, Jacobs HT, Szibor M, Xavier RJ, Braun T, Frezza C, Murphy MP and O’Neill LA (2016) Succinate Dehydrogenase Supports Metabolic Repurposing of Mitochondria to Drive Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell 167:457–470 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Zhu H, Kuppusamy P, Roubaud V, Zweier JL and Trush MA (1998) Validation of lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium) as a chemilumigenic probe for detecting superoxide anion radical production by enzymatic and cellular systems. J Biol Chem 273:2015–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–54. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Zhu H and Trush MA (1999) Detection of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species production by the chemilumigenic probes lucigenin and luminol. Biochim Biophys Acta 1428:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00040-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Zhu H, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL and Trush MA (2016) Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain-Derived Superoxide Exits Macrophages: Implications for Mononuclear Cell-Mediated Pathophysiological Processes. React Oxyg Species (Apex) 1:81–98. doi: 10.20455/ros.2016.815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munzel T, Afanas’ev IB, Kleschyov AL and Harrison DG (2002) Detection of superoxide in vascular tissue. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22:1761–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000034022.11764.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rembish SJ and Trush MA (1994) Further evidence that lucigenin-derived chemiluminescence monitors mitochondrial superoxide generation in rat alveolar macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 17:117–26. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90109-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas M and Solano F (1992) Coelenterazine is a superoxide anion-sensitive chemiluminescent probe: its usefulness in the assay of respiratory burst in neutrophils. Anal Biochem 206:273–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90366-f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarpey MM, White CR, Suarez E, Richardson G, Radi R and Freeman BA (1999) Chemiluminescent detection of oxidants in vascular tissue. Lucigenin but not coelenterazine enhances superoxide formation. Circ Res 84:1203–11. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(2020) Correction to: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 141:e33. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowding JM, Song W, Bossy K, Karakoti A, Kumar A, Kim A, Bossy B, Seal S, Ellisman MH, Perkins G, Self WT and Bossy-Wetzel E (2014) Cerium oxide nanoparticles protect against Abeta-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and neuronal cell death. Cell Death Differ 21:1622–32. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon HJ, Cha MY, Kim D, Kim DK, Soh M, Shin K, Hyeon T and Mook-Jung I (2016) Mitochondria-Targeting Ceria Nanoparticles as Antioxidants for Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Nano 10:2860–70. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b08045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussain S, Kodavanti PP, Marshburg JD, Janoshazi A, Marinakos SM, George M, Rice A, Wiesner MR and Garantziotis S (2016) Decreased Uptake and Enhanced Mitochondrial Protection Underlie Reduced Toxicity of Nanoceria in Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. J Biomed Nanotechnol 12:2139–50. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2016.2320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou X, Wang B, Jiang P, Chen Y, Mao Z and Gao C (2015) Uptake of cerium oxide nanoparticles and its influence on functions of mouse leukemic monocyte macrophages. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 17:28. doi: 10.1007/s11051-014-2815-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Stansbury KH, Zhu H and Trush MA (1999) Biochemical characterization of lucigenin (Bis-N-methylacridinium) as a chemiluminescent probe for detecting intramitochondrial superoxide anion radical production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 262:80–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arya A, Sethy NK, Das M, Singh SK, Das A, Ujjain SK, Sharma RK, Sharma M and Bhargava K (2014) Cerium oxide nanoparticles prevent apoptosis in primary cortical culture by stabilizing mitochondrial membrane potential. Free Radic Res 48:784–93. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.906593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cachat J, Deffert C, Hugues S and Krause KH (2015) Phagocyte NADPH oxidase and specific immunity. Clin Sci (Lond) 128:635–48. doi: 10.1042/CS20140635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bedard K and Krause KH (2007) The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu H (2016) Assays for Detecting Biological Superoxide. Reactive Oxygen Species 1:65–80. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.